Abstract

As graphene technologies progress to commercialization and large-scale manufacturing, issues of material and processing safety will need to be more seriously considered. The single word “graphene” actually represents a family of related materials with large variations in number of layers, surface area, lateral dimensions, stiffness, and surface chemistry. Many of these materials have aerodynamic diameters below 5 μm and can potentially be inhaled into the human lung. Graphene materials show several unique modes of interaction with biological molecules, tissues, and cells. The limited literature suggests that graphene materials can be either benign or harmful and that the biological response varies according to a material’s physicochemical properties and biologically effective dose. The present article reviews the current literature on the graphene–biological interface with an emphasis on the mechanisms and fundamental biological responses relevant to material safety and also to potential biomedical applications

Introduction

Environment, health, and safety have become critical issues for the successful commercialization of nanomaterial products. One might think that graphene would be an exception because extended monolayers on electronic substrates seem to pose little risk of large-scale exposures. As graphene research has expanded beyond nanoelectronics, however, interest has grown in related materials, including few-layer graphene (FLG), graphene oxide (GO), and other graphene-derived materials, that exist, at some stage in processing or use, as dry powders1 or aerosols.2 These materials are being developed for applications that include conducting polymers,3 battery electrodes,4,5 super-capacitors,6 printable inks,7 transport barriers,8,9 structural composites,3 antibacterial papers,6 and biomedical technologies,3,10,11 and in many cases, occupational exposures are probable. The interest in biological applications and implications (potential health risks) is centered not on pristine epitaxial monolayer graphene, but on these related forms. In general, graphene materials vary greatly in number of layers, lateral dimensions, and surface chemistry and are best regarded as a family of related materials, whose biological responses will vary much as they do across the carbon nanotube family.12–14 The structure–property variations in these graphene-family nanomaterials (GFNs) present significant challenges for the field of nanotoxicology, but also open up the potential for influencing safety through material design.12 At the same time, this material family offers potential opportunities for biological applications such as drug delivery.

Material properties relevant to biological effects

The literature on biological interactions of GFNs is sparse but growing rapidly, and aspects of it have been reviewed recently.1,15–17 The graphene properties most likely to determine biological response are surface area, number of layers, lateral dimensions, surface chemistry, and purity.

Surface area

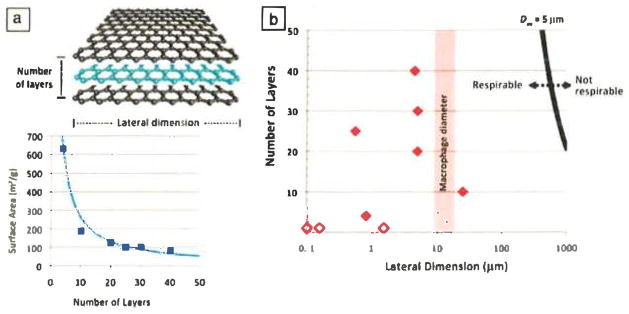

Surface area plays a central role in the biological interactions of nanomaterials.18 Small nanoparticles (<10 nm) have a significant fraction of their atoms exposed on their surfaces. Monolayer graphene represents an extreme case, in which every atom lies on the surface and, in fact, each atom is exposed to the surrounding medium on two sides, giving rise to the theoretical maximum specific surface area of an sp2-hybridized carbon sheet of about 2630 m2/g. As shown in Figure 1, the surface areas of other GFNs decrease as the number of layers, N, increases according to the scaling law A/m ~ 1/N, where A/m is the specific surface area, or total area per unit mass.

Figure 1.

Structure and property variations in graphene-family nanomaterials. (a) Number of layers determines surface area. A plot of the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller surface area (A) and vendor-specified numbers of layers (N) for commercial few-layer-graphene (FLG) samples (squares) agrees well with the simple law A = 2630/N m2/g (curve). (b) Ranges of N and lateral dimension L in various graphene materials. Solid symbols represent commercial FLG samples, and open symbols represent graphene oxide.19–21 The bold black curve shows a 5-μm aerodynamic diameter (Daa), calculated from N and L following Reference 1, which is assumed to separate respirable and nonrespirable materials.22 Most FLGs with L > 20 μm still lie in the respirable region (Daa < 5 μm) because they are ultrathin, but might not be cleared effectively following lung deposition. One commercial sample falls into this category.

Because of their high surface areas, surface phenomena such as physical adsorption and catalytic chemical reactions can affect the biological response to GFNs. The closest analogue to graphene is a pristine single-walled carbon nanotube (SWCNT), which is similarly hydrophobic and has a theoretical outer surface area of 1300 m2/g (although this surface area is significantly reduced in many cases to values below 500 m2/g by bundling). The high hydrophobic area of SWCNTs has been associated with the adsorption of molecular probe dyes and in vitro artifacts in toxicology assays,23,24 as well as the depletion of folic acid and other micronutrients from cell culture media, leading to cell growth inhibition.25 Adsorptive interferences have also been reported for carbon black26 and are expected for other materials with large hydrophobic surface areas, such as GFNs. The high surface areas of these materials make surface reactions potentially important, including deactivation of antioxidants27 and production and quenching of reactive oxygen species (ROS).28

Number of layers

The number of graphene layers in a stack is important because it determines specific surface area and bending stiffness. Simple geometric considerations for large, thin plates give A/m = 2/ρd, where ρ is the material density and d is the thickness. In turn, d is given by Nlayerd1, where Nlayer is the number of layers and d1 is the thickness of a single layer, which is 0.34 nm for unoxidized few-layer graphene (FLG). This yields

| (1) |

which shows that the specific surface area (m2/g) is inversely proportional to the number of layers (Figure 1). The adsorptive capacity for biological molecules is expected to increase significantly as the number of layers decreases. Stiffness is reported to be important in the pathological response to fibers and carbon nanotubes,13 but its role for platelike materials is still unknown. Thin materials, such as most GFNs, are quite deformable by weak forces such as water surface tension.19,29,30 In contrast, some multilayer-thick materials can act as rigid bodies during cellular interactions.

Lateral dimension

Lateral dimension has no significant effect on specific surface area (m2/g), but it is relevant for cell uptake, renal clearance, blood–brain barrier transport, and many other biological phenomena that determine the fate of particles in the body. The cellular uptake of platelike nanostructures, by either endocytosis into normal cells or phagocytosis into specialized macrophages, is poorly understood but is likely sensitive to lateral dimension, which represents the maximum dimension of the object being engulfed. The lateral sizes of GFNs span orders of magnitude (Figure 1), from 10 nm (the size of some proteins) to >20 μm (larger than some cells). Cells might thus adhere to and spread on larger GFNs, or successfully internalize smaller GFNs, or experience some form of frustrated endocytosis or phagocytosis with implications for biological risk. Sanchez et al.1 reported macrophage uptake of FLG samples with lateral dimensions of 0.5 μm, 0.88 μm, and 5 μm, but not 25 μm, although even a 25-μm sample is likely respirable because of its ultrathin third dimension (Figure 1), as also reported and discussed by Schinwald et al.22

Surface chemistry

The graphene family includes materials with widely varying surface chemistries, even before any specific biofunctionalization is carried out. Graphene oxide surfaces are partially hydrophilic (typical water contact angle of 40–50°),31,32 are capable of hydrogen bonding and metal-ion complexing,33 and contain negative charges on edge sites associated with carboxyl groups.34 The pristine graphene surface, in contrast, is hydrophobic (water contact angle near 90°)35 and capable of adsorbing biomolecules or being partitioned into membranes by hydrophobic forces. Pristine graphene is capable of biochemical reactions primarily at edge or defect sites. Reduced graphene oxide is intermediate in hydrophilicity and in reactivity, as it contains vacancy defects produced during oxygen removal.36 Much of the biomedical work has been done on nanoscale GO because of its higher dispersibility in aqueous phases. Pristine graphenes (monolayer or FLG) are very poorly dispersible in water and require surfactants or other stabilizing agents for any meaningful application requiring suspension in biological fluids.

Purity

Unlike carbon nanotubes (CNTs), GFNs are not typically grown catalytically and do not contain residual metal catalysts. However, some GFNs might contain residual intercalants, chemical additives used to separate the layers in the bulk graphite feedstock, that were not fully removed by washing.37 GO synthesis uses a variety of reagents that can leave soluble residues in suspension if they are not properly washed, and the washing of GO can be tedious because of gelation caused by physical interactions between the giant molecular disks.37 The reagents used in various GFN syntheses include permanganate, nitrate, sulfate, chromate, peroxide, persulfate, and hydrazine. GO can also contain lower-molecular-weight oxidative debris that is noncovalently attached to the primary sheets,38 and the biological response to this organic material is unknown.

Biomolecular interactions

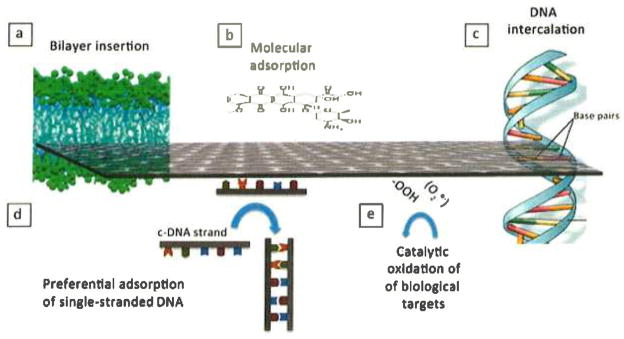

GFNs interact with biological molecules in a number of characteristic ways, as summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Characteristic biomolecular interactions of graphene materials. (a) Interleaflet insertion into the hydrophobic core of a lipid bilayer as predicted by coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations.39 (b) Small-molecule adsorption driven by hydrophobic and π–π interactions and relevant to micronutrient and dye adsorption,25 as well as drug delivery using nanoscale graphene oxide (GO).20,40–42 (c) DNA intercalation in nanoscale GO in the presence of copper cations.43 (d) Preferential adsorption of single-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid (ssDNA) over double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) on GO;44,45 c-DNA is complementary DNA. The preference for ssDNA is likely related to base–graphene interactions, which are shielded in dsDNA, thus favoring desorption.44 (e) Oxidative damage to biological target molecules through bound oxygen intermediates on edge and defect sites.46

Small-molecule and ion adsorption

A defining characteristic of GFNs is high surface area, which should lead to the adsorption of small-molecule solutes from physiological fluids (Figure 2b). Adsorption on carbon surfaces is generally favored for molecules with low solubility, partial hydrophobicity, or positive charge (for the common case of negatively charged graphene) and for molecules with conjugated π bonds that impart planarity and allow π–π interactions with graphenic carbon surfaces. The biological consequences might include (1) micronutrient depletion;25 (2) artifacts in assays that rely on dye-based molecular probes;23,24 (3) the capacity to carry small-molecule drug cargoes;47 and (4) synergistic or antagonistic toxic effects when graphenes coexist with small-molecule toxicants, whose bioavailability can be increased or decreased as they partition to graphene surfaces.

Most attention on small-molecule interactions has been related to drug delivery, where functionalized nanoscale GO has been used as a carrier for small-molecule drugs, 11,20,40,48 including the cancer drugs doxorubicin,11,20 chlorin e6,40 and camptothecin.11 The adsorption sites for conjugated molecules are believed to be unfunctionalized sp2 graphenic domains that exist as a patchwork between oxygenated sites on the GO basal plane.

DNA/RNA interactions

The most active area of research on GFN biomolecular interactions involves those with DNA and RNA.21,41,43,45,49 GFNs show several unique modes of interaction with DNA and RNA, including intercalation into DNA by GFNs of small lateral dimension (Figure 2c),43 preferential adsorption of single-stranded (ss) over double-stranded (ds) forms (Figure 2d),44,49 and steric protection of adsorbed nucleotides from attack by nuclease enzymes.49 Ren et al.43 reported DNA cleavage under conditions where Cu2+ is present but is not active on its own. It appears that this behavior relies on a combination of the planar single-atom-thick GO structure, which can be inserted in the molecular spaces between base pairs, and the peripheral COOH groups that provide sites for Cu2+ binding (Figure 2c).

Selective adsorption of ssDNA over dsDNA and protection from degradative enzymes make GO attractive in DNA or RNA delivery and sensing, especially when used in the form of <100-nm “nanosheets” that have the advantages of good dispersibility, colloidal stability, cell uptake, and low toxicity. The preferential binding of ssDNA to GO is believed to reflect the role of GO–base interactions in ssDNA adsorption. DNA is a polyanion and is electrostatically repelled from GO, but the DNA bases can bind to graphenic surfaces (Figure 2d) through hydrophobic forces and π–π stacking.44 These latter attractive forces can overcome the electrostatic repulsion, especially at high ionic strength, where electrolytes shield the charges, or at low pH, where the charge on GO is reduced by protonation. In dsDNA, the bases are protected inside the double helix (Figure 2d), and the outer charged phosphate groups show low affinity for GO surfaces.

Catalysis of oxidative reactions

Oxidative stress is a common toxicity pathway for nanomaterials and has been reported to occur upon exposure of A549 lung-cell cultures to GO.50 Nanosurfaces can generate ROS, which are intermediates along the reduction pathway of molecular oxygen to water, and include HO·, O2·−, and H2O2. Recently, Liu et al.46 reported that a range of carbon nanomaterials, including GO, deactivated the antioxidant glutathione by catalyzing its reaction with O2. The primary ROS in this study are bound oxygen complexes on edge or defect sites (Figure 2e), which oxidize the biological target, glutathione. Graphene oxide has significant catalytic activity for this model reaction and could thus mediate oxidative damage in living systems, although it shares this property with other members of the carbon nanomaterial family such as nanotubes and carbon black.

Human exposure potential

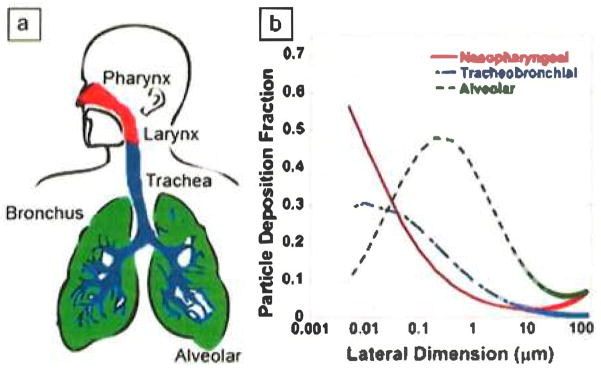

Humans can be exposed to nanomaterials through inhalation, dermal (skin) contact, ingestion, or direct injection. Direct injection is relevant for GO-based biomedical therapies,11,51,52 and inhalation of graphene-based powders is likely the main concern for unintended exposures. Figure 1 divides the graphene and graphite family into potentially respirable and nonrespirable categories. When respirable particles are inhaled, they can deposit in one of three regions (Figure 3a): nasopharyngeal, tracheobronchial, and alveolar. The nasopharyngeal region includes the nose, mouth, pharynx, and larynx. The trachea, bronchi, and bronchioles form the tracheobronchial region of the lung. The alveolar region contains the alveoli and is where gas exchange takes place.

Figure 3.

(a) Depiction of the three regions in which respirable particles can be deposited when inhaled: nasopharyngeal, tracheobronchial, and alveolar. Note that the nasopharyngeal region includes the nose, mouth, pharynx, and larynx. (b) Calculated fractional depositions of inhaled graphene-family nanomaterials (GFNs) in the nasopharyngeal, tracheobronchial, and alveolar regions of the human respiratory tract. Lateral dimensions of the GFNs range from 0.005 to 100 μm. GFNs are assumed to be 0.34 nm (one layer) thick and traveling along the polar axis. Figure modified from Sanchez et al.1

Figure 3b shows the fractions of inhaled GFNs of different sizes deposited in the nasopharyngeal, tracheobronchial, and alveolar regions of the human respiratory tract based on theoretical deposition models.1 These calculations assume that particles are inhaled as individual particles and not as aggregates. Substantial amounts of GFNs can deposit in each of the three regions. Deposition of particulates in the nasopharyngeal and tracheobronchial airways serves to protect the alveolar region from harmful materials.

Upon deposition in the human respiratory tract, GFNs will encounter several structural elements: (a) a surfactant film at the air–liquid interface in the air spaces and the aqueous mucus layer lining the nasopharyngeal and tracheobronchial airways; (b) phagocytic cells called macrophages submerged in the aqueous phase; (c) respiratory epithelial cells; and (d) tissues, lymphatic vessels, immune cells, and blood vessels in the air spaces. Thus, the inner surface of the lungs functions as a physical, biochemical, and immunological barrier, separating outside from inside.

For particles that deposit in the nasopharyngeal and tracheobronchial airways, retention time can be short as a result of efficient clearance. Specifically, the epithelial cells in this region are lined with hairlike “cilia” that beat in a coordinated rhythmic fashion. Cilia are immersed in a thick liquid film of mucus that traps foreign particles and microorganisms. The beating cilia transport the particle-laden mucus towards the pharynx, where it is either swallowed (leading to an ingestion exposure) or expelled by coughing. This mode of clearance in the human respiratory tract is called mucociliary clearance, and the pathway is the “mucociliary escalator.” The alveolar region is involved in gas exchange and does not have such a protective mucus barrier. Instead, specialized cells called alveolar macrophages ingest particles through phagocytosis and clear them by transport to lymph nodes, although generally this process can take months or years. The ability of macrophages to successfully phagocytize platelike graphene particles and retain sufficient motility for clearance is not well characterized, and there is a need for more research in this area.

Biological responses and potential human health impacts

Occupational exposures

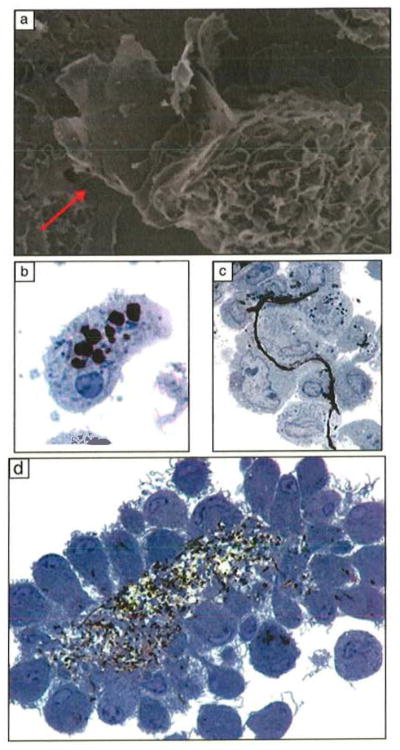

Some graphene materials are similar in size and shape to known platelike minerals such as talc, mica, slate, and Fuller’s earth,53 although their chemistry is very different. Mining and manufacturing using these naturally occurring minerals can induce scattered areas of dust accumulation and lung granulomas following inhalation into the respiratory tract.53 The conducting airways of the lungs and air spaces or alveoli are covered by macrophages, which are the initial defense (after physical barriers) against inhaled particulates and microorganisms.54 As illustrated in Figure 4, macrophages rapidly engulf or phagocytize platelike GFNs of small lateral dimension.

Figure 4.

Macrophage interactions with carbon nanomaterials. (a) Partial uptake of an FLG sheet 20 layers thick and 5 μm in lateral dimension. (Scanning electron micrograph, 10,500x magnification.) (b) Complete uptake of FLG sheets, 20–30 layers thick and 550 nm in lateral dimension. (c) Attachment of macrophages to the surfaces of a single FLG sheet, 10 layers thick and 25 μm in lateral dimension. Parts (b) and (c) reproduced with permission from Reference 1. ©2012, American Chemical Society. (d) Activated macrophages in nonadherent, three-dimensional cultures aggregate around carbon nanotubes to form a granuloma. Images (b)–(d) are 0.5-μm plastic-embedded sections, toluidine blue stain, light microscopy, 1000x magnification.55,56 Part (d) reproduced with permission from Reference 14. ©2011, BioMed Central Ltd.

Following phagocytosis, smaller particulates are sequestered in acidic (pH ~4.5) cytoplasmic vesicles called lysosomes that contain hydrolytic enzymes capable of degrading biological macromolecules including lipids, proteins, carbohydrates, and nucleic acids.57 If inhaled microorganisms and particulates cannot be killed or degraded in lysosomes, additional macrophages are recruited from the peripheral blood and undergo activation.58 As illustrated in Figure 4, activated macrophages have prominent surface ruffles and produce a variety of chemical mediators that can amplify the initial inflammatory response.59 Direct delivery of carbon nanotubes into the lungs of rodents induces persistent inflammation and fibrosis or fibrous scarring.1,60 It is likely that platelike GFNs that are larger in diameter than a macrophage (~10 μm) cannot be phagocytized (see Figure 4c) and will induce the macrophages to aggregate into a granuloma and cause sustained inflammation in the lungs.

Recent experimental work has investigated potential lung toxicity of GFNs. Duch et al.61 compared the toxicity of graphene flakes and GO using mouse lung macrophages or epithelial cells in vitro. Well-dispersed graphene flakes did not induce toxicity in these lung target cells. In contrast, GO causes excess mitochondrial generation of ROS and cell death by apoptosis. Duch et al. speculated that GO can escape from lysosomes into the cytoplasm and participate in the electron-transport chain located in mitochondria, generating excess ROS and thereby leading to cell death.

Other investigators62 have also shown that GO is toxic to lung epithelial cells and generates ROS extracellularly even in the absence of cell uptake.50,63 Duch et al.61 also induced significant acute lung injury and sustained inflammation after a single intratracheal delivery of 50 μg of GO into the lungs of mice. Dispersed graphene did not induce lung injury or inflammation, whereas aggregated graphene blocked the small conducting airways and produced a focal fibrotic scar. FLG nanoplatelets also induce inflammation, incomplete phagocytosis, and aggregation of macrophages following nasopharyngeal aspiration (50 μg) into the lungs or direct injection (5 μg) into the pleural space of mice.22

Potential toxicity in biomedical applications

Like other materials based on elemental carbon, GFNs have the potential to be biocompatible, and carbon nanomaterials have been explored for applications as biomedical implants, biological sensors, and drug-delivery devices.1,15,64 In comparison with SWCNTs, GO has a higher specific surface area and can be functionalized, dispersed in biological media, and produced in large quantities at lower cost.15 Similarly to other drug-delivery platforms, graphene nanosheets and GO can be coated with polymers such as poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)42 or chitosan65 to prolong circulation time and enhance biocompatibility. For example, Yang et al.52 produced PEG-coated GO sheets in the size range of 10–50 nm that were nontoxic up to 40 days following intravenous injection in mice. These nanoscale coated GO sheets showed excellent passive uptake into tumor xenografts in mice and allowed successful photothermal tumor ablation.

Nanoscale drug delivery following intravenous administration can lead to systemic distribution to secondary target organs including the liver and spleen, as illustrated in Figure 5. Feng and Liu14 reported that nanoscale PEG-coated GO sheets initially accumulated in these organs and were then gradually excreted with no indication of toxicity after three months.67 On the other hand, Wang et al.62 and Zhang et al.68 reported that intravenous injection of uncoated GO sheets induced granulomas in the lungs,62,68 liver, spleen, and kidneys at a dose of 0.4 mg per mouse. Intravenous delivery of GO nanosheets might also induce the breakdown of red blood cells (hemolysis),65,68 and graphene nanosheets have been found to induce red blood cell aggregation in vitro.65 These studies confirm the importance of surface functionalization and aggregation state on the potential toxicity of GFNs.

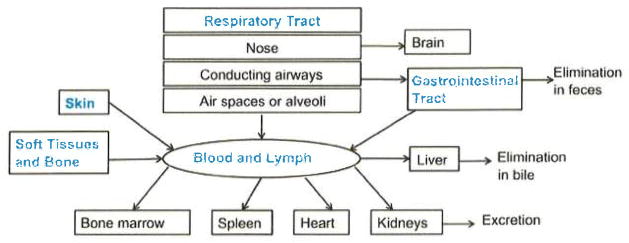

Figure 5.

Routes of exposure, systemic distribution, and elimination of nanomaterials from the body following skin contact, implantation into soft tissues and bone, intravenous injection, inhalation into the respiratory tract, and ingestion. Figure modified from Obderdörster et al.66

A final consideration regarding the long-term toxicity of GFNs used in biomedical applications is biopersistence. Non-biodegradable implants with smooth, continuous surfaces induce foreign-body tumors following implantation in rodents.69 High-surface-area GFNs with smooth surface topography and biopersistence70 have the potential to induce chronic inflammation with persistent generation of ROS that have been linked with the pathogenesis of foreign-body tumors.71 GFNs can be engineered deliberately to promote biodegradation, as demonstrated for carbon nanotubes.55,72,73 In addition, GO is susceptible to degradation by enzymatic oxidation.74

Environmental impacts and manufacturing safety

Many human exposures to toxic materials do not occur in the laboratory or workplace, but rather involve release to the environment, followed by transport, chemical transformation, uptake by organisms and/or bioaccumulation, and return to humans through food. Nanomaterials could affect environmental organisms or ecosystems or impact human health following ingestion, inhalation, or skin contact. In 2011, the annual commercial production of graphene totaled around 15 tons, and it could grow more than 12-fold in the upcoming year.75 This growth, coupled with the great interest in graphene applications, suggests the need for more research on environmental implications.

We are unaware of articles on the environmental fate and transport of graphenes, although there have been several studies of environment applications, primarily as sorbents.76–81 Nanomaterials can transform in the environment, and Salas et al.82 reported that common bacteria from the genus Shewanella can reduce GO under environmentally relevant conditions, which would be expected to alter its transport and partitioning. Kotchey et al.74 also reported that GO, but not reduced graphene oxide, is susceptible to oxidative attack by hydrogen peroxide and horseradish peroxidase. In one of the first ecotoxicity studies, Begum et al.83 reported dose-dependent adverse effects on plant growth in the presence of GO at concentrations ranging from 500 to 2000 mg/l. More work is needed to understand the biological and environmental stability of graphene materials.22

Other manufacturing issues

The chemical synthesis of GO can lead to explosions associated with Cl2O gas, which is a byproduct of the use of potassium chlorate as an oxidizer,84 or residual acetone, which is commonly used to clean glassware.85 Like all carbon materials, graphene and GO can be oxidized, but not all forms are easily ignitable. Kim et al.37 reported that GO papers containing residual salts from the synthesis process are highly flammable as a result of catalytic oxidation. Local heating can induce GO reduction, the exothermicity of which ignites the paper in a coupled reduction/combustion process. This effect can be suppressed by removing salt using additional purification steps.37 As manufacturing volume grows, so will interest in producing graphenes in a cost-effective and sustainable manner. The competing methods (chemical vapor deposition, exfoliation, GO wet synthesis) use very different types of processing and are likely to have very different energy usages, raw material and waste productions, and overall sustainability indices. Safe and sustainable graphene manufacture on a large scale is a promising area for future research and life-cycle assessment.

Summary

Graphene materials are the basis for a number of exciting technologies, but much more research is needed to understand their biological interactions and safety. There is a particular need for basic cellular-toxicity and inhalation studies, measurements of workplace concentrations, investigations of macrophage uptake and clearance of platelike objects, and studies on environmental and biopersistence, all with a focus on the wide range of properties of graphene materials. In the meantime, both research and development and manufacturing workers should minimize their exposure using best control practices. Protective measures for conventional insoluble particulates, including respirators, high-efficiency particulate-arresting (HEPA) filters, and other personal protective equipment already used in powder processing, are likely to prove effective against graphene/graphene oxide as well.

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this work was provided by the NIEHS Superfund Research Program P42 ES013660, NSF CBET-1132446, NIEHS T32 ES007272 Training Grant (A.C.J.), and US Department of Education GAANN fellowship grant P200A090076 (M.C.).

Contributor Information

Ashish C. Jachak, Email: Ashish_Jachak@brown.edu, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Brown University

Megan Creighton, Email: Megan_Creighton@brown.edu, School of Engineering, Brown University.

Yang Qiu, Email: Yang_Qiu@brown.edu, School of Engineering, Brown University.

Agnes B. Kane, Email: Agnes_Kane@brown.edu, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Brown University

Robert H. Hurt, Email: Robert_Hurt@brown.edu, School of Engineering and Institute for Molecular and Nanoscale Innovation, Brown University

References

- 1.Sanchez VC, Jachak A, Hurt RH, Kane AB. Cham Res Toxicol. 2012;25:15. doi: 10.1021/tx200339h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luo J, Jang HD, Sun T, Xiao L, He Z, Katsoulidis AP, Kanatzidis MG, Gibson JM, Huang J. ACS Nano. 2011;5:8943. doi: 10.1021/nn203115u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stankovich S, Dikin DA, Dommett GH, Kohlhaas KM, Zimney EJ, Stach EA, Piner RD, Nguyen ST, Ruoff RS. Nature. 2006;442:282. doi: 10.1038/nature04969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paek SM, Yoo E, Honma I. Nano Lett. 2009;9:72. doi: 10.1021/nl802484w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Su FY, You CH, He YB, Lv W, Cui W, Jin FM, Li BH, Yang QH, Kang FY. J Mater Chem. 2010;20:9644. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dikin DA, Stankovich S, Zimney EJ, Piner RD, Dommett GH, Evmenenko G, Nguyen ST, Ruoff RS. Nature. 2007;448:457. doi: 10.1038/nature06016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang S, Ang PK, Wang ZQ, Tang ALL, Thong JTL, Loh KP. Nano Lett. 2010;10:92. doi: 10.1021/nl9028736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bunch JS, Verbridge SS, Alden JS, van der Zande AM, Parpia JM, Craighead HG, McEuen PL. Nano Lett. 2008;8:2458. doi: 10.1021/nl801457b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Compton OC, Kim S, Pierre C, Torkelson JM, Nguyen ST. Adv Mater. 2010;22:4759. doi: 10.1002/adma.201000960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ryoo SR, Kim YK, Kim MH, Min DH. ACS Nano. 2010;4:6587. doi: 10.1021/nn1018279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang LM, Xia JG, Zhao QH, Liu LW, Zhang ZJ. Small. 2010;6:537. doi: 10.1002/smll.200901680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hurt RH, Monthioux M, Kane A. Carbon. 2006;44:1028. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poland CA, Duffin R, Kinloch I, Maynard A, Wallace WA, Seaton A, Stone V, Brown S, Macnee W, Donaldson K. Nat Nanotechnol. 2008;3:423. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanchez VC, Weston P, Yan A, Hurt RH, Kane AB. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2011;8:17. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-8-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng L, Liu Z. Nanomedicine (London, UK) 2011;6:317. doi: 10.2217/nnm.10.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuila T, Bose S, Khanra P, Mishra AK, Kim NH, Lee JH. Biosens Bioelectron. 2011;26:4637. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2011.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shao YY, Wang J, Wu H, Liu J, Aksay IA, Lin YH. Electroanalysis. 2010;22:1027. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nel AE, Madler L, Velegol D, Xia T, Hoek EMV, Somasundaran P, Klaessig F, Castranova V, Thompson M. Nat Mater. 2009;8:543. doi: 10.1038/nmat2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo F, Kim F, Han TH, Shenoy VB, Huang J, Hurt RH. ACS Nano. 2011;5:8019. doi: 10.1021/nn2025644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun X, Liu Z, Welsher K, Robinson JT, Goodwin A, Zaric S, Dai H. Nano Res. 2008;1:203. doi: 10.1007/s12274-008-8021-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y, Li Z, Hu D, Lin CT, Li J, Lin Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:9274. doi: 10.1021/ja103169v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schinwald A, Murphy FA, Jones A, Macnee W, Donaldson K. ACS Nano. 2012;6:736. doi: 10.1021/nn204229f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Casey A, Herzog E, Davoren M, Lyng FM, Byrne HJ, Chambers G. Carbon. 2007;45:1425. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Worle-Knirsch JM, Pulskamp K, Krug HF. Nano Lett. 2006;6:1261. doi: 10.1021/nl060177c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo L, Bussche AV, Buechner M, Yan AH, Kane AB, Hurt RH. Small. 2008;4:721. doi: 10.1002/smll.200700754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monteiro-Riviere NA, Inman AO. Carbon. 2006;44:1070. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu XY, Gurel V, Morris D, Murray DW, Zhitkovich A, Kane AB, Hurt RH. Adv Mater. 2007;19:2790. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fenoglio I, Tomatis M, Lison D, Muller J, Fonseca A, Nagy JB, Fubini B. Free Radical Biol Med. 2006;40:1227. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bellido EP, Seminario JM. J Phys Chem. 2010;C114:22472. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patra N, Wang BY, Kral P. Nano Lett. 2009;9:3766. doi: 10.1021/nl9019616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hasan SA, Rigueur JL, Harl RR, Krejci AJ, Gonzalo-Juan I, Rogers BR, Dickerson JH. ACS Nano. 2010;4:7367. doi: 10.1021/nn102152x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hsieh CT, Chen WY. Surf Coat Technol. 2011;205:4554. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang ST, Chang Y, Wang H, Liu G, Chen S, Wang Y, Liu Y, Cao A. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2010;351:122. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2010.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cote LJ, Kim F, Huang J. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:1043. doi: 10.1021/ja806262m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kotsalis EM, Demosthenous E, Walther JH, Kassinos SC, Koumoutsakos P. Chem Phys Lett. 2005;412:250. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bagri A, Mattevi C, Acik M, Chabal YJ, Chhowalla M, Shenoy VB. Nat Chem. 2010;2:581. doi: 10.1038/nchem.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim F, Cote LJ, Huang J. Adv Mater. 2010;22:1954. doi: 10.1002/adma.200903932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rourke JP, Pandey PA, Moore JJ, Bates M, Kinloch IA, Young RJ, Wilson NR. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2011;50:3173. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Titov AV, Kral P, Pearson R. ACS Nano. 2010;4:229. doi: 10.1021/nn9015778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang P, Xu C, Lin J, Wang C, Wang X, Zhang C, Zhou X, Guo S, Cui D. Theranostics. 2011;1:240. doi: 10.7150/thno/v01p0240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bao H, Pan Y, Ping Y, Sahoo NG, Wu T, Li L, Li J, Gan LH. Small. 2011;7:1569. doi: 10.1002/smll.201100191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu Z, Robinson JT, Sun X, Dai H. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:10876. doi: 10.1021/ja803688x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ren H, Wang C, Zhang J, Zhou X, Xu D, Zheng J, Guo S. ACS Nano. 2010;4:7169. doi: 10.1021/nn101696r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu M, Kempaiah R, Huang PJ, Maheshwari V, Liu J. Langmuir. 2011;27:2731. doi: 10.1021/la1037926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu Y, Wu Q, Sun Y, Bai H, Shi G. ACS Nano. 2010;4:7358. doi: 10.1021/nn1027104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu X, Sen S, Liu J, Kulaots I, Geohegan D, Kane A, Puretzky AA, Rouleau CM, More KL, Palmore GT, Hurt RH. Small. 2011;7:2775. doi: 10.1002/smll.201100651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang XY, Wang YS, Huang X, Ma YF, Huang Y, Yang RC, Duan HQ, Chen YS. J Mater Chem. 2011;21:3448. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang W, Guo Z, Huang D, Liu Z, Guo X, Zhong H. Biomaterials. 2011;32:8555. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lu CH, Zhu CL, Li J, Liu JJ, Chen X, Yang HH. Chem Commun. 2010;46:3116. doi: 10.1039/b926893f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chang Y, Yang ST, Liu JH, Dong E, Wang Y, Cao A, Liu Y, Wang H. Toxicol Lett. 2011;200:201. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2010.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tian B, Wang C, Zhang S, Feng L, Liu Z. ACS Nano. 2011;5:7000. doi: 10.1021/nn201560b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang K, Zhang S, Zhang G, Sun X, Lee ST, Liu Z. Nano Lett. 2010;10:3318. doi: 10.1021/nl100996u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Churg A, Green FHY, editors. Pathology of Occupational Lung Disease. 2. Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore, MD: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Geiser M. Microsc Res Tech. 2002;57:512. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Allen BL, Kichambare PD, Gou P, Vlasova II, Kapralov AA, Konduru N, Kagan VE, Star A. Nano Lett. 2008;8:3899. doi: 10.1021/nl802315h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Compton OC, Nguyen ST. Small. 2010;6:711. doi: 10.1002/smll.200901934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Haas A. Traffic. 2007;8:311. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lehnert BE. Environ Health Perspect. 1992;97:17. doi: 10.1289/ehp.929717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Martinez FO, Helming L, Gordon S. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:451. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Card JW, Zeldin DC, Bonner JC, Nestmann ER. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295:L400. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00041.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Duch MC, Budinger GR, Liang YT, Soberanes S, Urich D, Chiarella SE, Campochiaro LA, Gonzalez A, Chandel NS, Hersam MC, Mutlu GM. Nano Lett. 2011;11:5201. doi: 10.1021/nl202515a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang K, Ruan J, Song H, Zhang JL, Wo Y, Guo SW, Cui DX. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2011;6:8. doi: 10.1007/s11671-010-9751-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang Y, Ali SF, Dervishi E, Xu Y, Li Z, Casciano D, Biris AS. ACS Nano. 2010;4:3181. doi: 10.1021/nn1007176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu Z, Tabakman S, Welsher K, Dai H. Nano Res. 2009;2:85. doi: 10.1007/s12274-009-9009-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liao KH, Lin YS, Macosko CW, Haynes CL. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2011;3:2607. doi: 10.1021/am200428v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Oberdorster G, Oberdorster E, Oberdorster J. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:823. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang K, Wan J, Zhang S, Zhang Y, Lee ST, Liu Z. ACS Nano. 2011;5:516. doi: 10.1021/nn1024303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang XY, Yin JL, Peng C, Hu WQ, Zhu ZY, Li WX, Fan CH, Huang Q. Carbon. 2011;49:986. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Oppenheimer ET, Willhite M, Danishefsky I, Stout AP. Cancer Res. 1961;21:132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Soldano C, Mahmood A, Dujardin E. Carbon. 2010;48:2127. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Okada F. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:2364. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kagan VE, Konduru NV, Feng W, Allen BL, Conroy J, Volkov Y, Vlasova II, Belikova NA, Yanamala N, Kapralov A, Tyurina YY, Shi J, Kisin ER, Murray AR, Franks J, Stolz D, Gou P, Klein-Seetharaman J, Fadeel B, Star A, Shvedova AA. Nat Nanotechnol. 2010;5:354. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liu XY, Hurt RH, Kane AB. Carbon. 2010;48:1961. doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kotchey GP, Allen BL, Vedala H, Yanamala N, Kapralov AA, Tyurina YY, Klein-Seetharaman J, Kagan VE, Star A. ACS Nano. 2011;5:2098. doi: 10.1021/nn103265h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Segal M. Nat Nanotechnol. 2009;4:612. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chandra V, Park J, Chun Y, Lee JW, Hwang IC, Kim KS. ACS Nano. 2010;4:3979. doi: 10.1021/nn1008897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gao Y, Li Y, Zhang L, Huang H, Hu J, Shah SM, Su X. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2011;368:540. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2011.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li YH, Zhang P, Du QJ, Peng XJ, Liu TH, Wang ZH, Xia YZ, Zhang W, Wang KL, Zhu HW, Wu DH. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2011;363:348. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2011.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang C, Feng C, Gao YJ, Ma XX, Wu QH, Wang Z. Chem Eng J. 2011;173:92. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wu QH, Zhao GY, Feng C, Wang C, Wang Z. J Chromatogr A. 2011;1218:7936. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2011.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wu T, Cai X, Tan S, Li H, Liu J, Yang W. Chem Eng J. 2011;173:144. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Salas EC, Sun Z, Luttge A, Tour JM. ACS Nano. 2010;4:4852. doi: 10.1021/nn101081t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Begum P, Ikhtiari R, Fugetsu B. Carbon. 2011;49:3907. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Marcano DC, Kosynkin DV, Berlin JM, Sinitskii A, Sun ZZ, Slesarev A, Alemany LB, Lu W, Tour JM. ACS Nano. 2010;4:4806. doi: 10.1021/nn1006368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lee S, Oh J, Ruoff RS, Park S. Carbon. 2012;50:1442. [Google Scholar]