Abstract

There is an urgent need to develop a better method of contraception which is non-steroidal and reversible to control world population explosion and unintended pregnancies. Contraceptive vaccines (CV), especially targeting sperm-specific proteins, can provide an ideal contraceptive modality. Sperm-specific proteins can induce an immune response in women as well as men, thus can be used for CV development in both sexes. In this article, we will review two sperm-specific proteins, namely Izumo protein and YLP12 dodecamer peptide. Gene-knockout studies indicate that Izumo protein is essential for sperm–egg membrane fusion. Vaccination with Izumo protein or its cDNA causes a significant reduction in fertility of female mice. The antibodies to human Izumo inhibit human sperm penetration assay. Recently, our laboratory found that a significant percentage of infertile women have antibodies to Izumo protein. The second sperm-specific protein is YLP12, a peptide mimetic sequence present on human sperm involved in recognition and binding to the human oocyte zona pellucida. Vaccination with YLP12 or its cDNA causes long-term, reversible contraception, without side effects, in female mice. Infertile, but not fertile, men and women have antibodies to YLP12 peptide. Our laboratory has isolated, cloned, and sequenced cDNA encoding human single chain variable fragment (scFv) antibody from infertile men which reacts with YLP12 peptide. The human YLP12 scFv antibody may provide a novel passive immunocontraceptive, the first of its kind. In conclusion, sperm-specific Izumo protein and YLP12 peptide can provide exciting candidates for antisperm CV development.

Keywords: vaccines, contraception, Izumo, sperm protein, YLP12, protein science

Introduction

Protein science is an interesting discipline to delineate structure–function relationship of a protein molecule. In this review, we will explore the application of protein science in the development of contraceptive vaccines (CV) for humans, targeting two exciting sperm-specific molecules, namely Izumo protein and YLP12 dodecamer peptide, which have drawn considerable attention.

Population explosion and unintended pregnancies resulting in elective abortion are major public health issues worldwide. World population is more than 7.138 billion and increasing by one billion every 11 years.1 In the first year AD, the world population was 250 million, which increased to one billion by 1830. It took next 100 years for population to increase by one billion. In the United States, half of all pregnancies are unintended due to contraceptive failure, resulting in more than one million elective abortions annually.2,3 An estimated 80 million women have unintended/unwanted pregnancies worldwide annually, of which 45 million are electively aborted.4 Thus, there is an urgent need for a better method of contraception which is acceptable and available both in the developed and developing nations and can be used by both men and women. An ideal contraceptive should be non-steroidal, nonbarrier, non-surgical, intercourse-independent, and reversible. CV can provide a modality which can meet all the standards of an ideal contraceptive. As the developed and most of the developing nations have an infrastructure for mass immunization, vaccines for contraception will have wider acceptability.

Sperm can provide an ideal target for CV development. Sperm can produce antisperm antibodies (ASA) in both men and women, allowing for CV development for both sexes. Up to 70% of vasectomized men produce ASA,5 and 2%–30% of infertility cases are associated with the presence of ASA in the male and/or female partner of an infertile couple.6 Infertility caused by ASA is defined as immunoinfertility. ASA can affect fertility through several mechanisms, including: inhibition of sperm motility, capacitation, acrosome reaction, sperm-zona interaction, sperm-oolemma binding and penetration, and preimplantation embryonic development. Animal7–9 and human10,11 studies have shown that deliberate immunization of males and females with sperm causes contraception. In a classic study, Baskin10 injected 20 fertile women, known to have at least one prior pregnancy, with their husband's semen. These women developed ASA and no conception was reported for up to 1 year of observation. These findings provide strong evidence that spermatozoa are capable of eliciting an immune response that can cause contraception. A US patent was issued for this spermatoxic vaccine in 1937 (US patent number 2103240). However, whole sperm cannot be used for CV development as it has several proteins that are likely to be shared with various somatic cells.12 Only sperm-specific proteins can be used for CV development. The utility of a sperm protein for CV development is contingent upon its: (a) sperm-specificity, (b) sperm-surface expression, (c) involvement in fertility, and (d) ability to raise high antibody titers, especially in the genital tract. A sperm protein which has these properties and is also involved in human immunoinfertility is a promising and exciting candidate for CV. As immunoinfertile patients have no other tissue pathology concomitant with infertility, it indicates the sperm specificity of that molecule in humans.

Several sperm proteins have been delineated in our and various laboratories for CV development.12–14 Some of these proteins have shown an effect on fertilization in vitro. Only a few of these have also shown an effect on fertility in animals in vivo.12–14 Of these, two sperm proteins are of special interest because of the reasons discussed below. In this review, we will focus on these two sperm-specific proteins, namely Izumo protein and YLP12 dodecamer peptide, which have drawn considerable attention.

Izumo Protein

Mouse model

Discovery and protein science

The mouse genome is approximately 2.8 billion DNA letters long. It is about 14% shorter than the human genome, which is 3.24 billion letters long. The human genome has more repeat sequences than the mouse genome.15–17 Both genomes seem to contain approximately 21,000–23,000 protein coding genes.15–17 A majority of them are evolutionarily conserved and some families of genes have undergone expansion/multiplication in the mouse lineage.15–17 More than 100 proteins have been identified that are expressed on mature sperm surface at the site of sperm–oocyte interactions.18

A sperm protein Izumo was first delineated using a monoclonal antibody, OBF13, against mouse sperm that specifically inhibits sperm–oocyte membrane fusion.19,20 This antibody specifically reacts with a protein spot of mouse sperm extract, resolved in two-dimensional electrophoresis and Western blot procedures.21 This peptide spot was analyzed by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), and 10 peptides were found that were 100% identical to a part of the sequence listed in the RIKEN full-length database [National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) accession number XM_133424]. The antibody did not react with any protein band in any other murine tissue tested. This testis/sperm-specific protein was designated as “Izumo” after a Japanese shrine dedicated to marriage.21 Izumo is a 377 amino acid transmembrane glycoprotein with a large extracellular region, a single transmembrane region, and a short cytoplasmic tail. Izumo is a novel member of the immunoglobulin superfamily (IgSF) of proteins. It shows a protein band of approximately 56 kDa in sodium dodecyl sulfate-gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). It has a 319 amino acid extracellular region which has one immunoglobulin-like domain. It is N-glycosylated; however, glycosylation is not essential for functional activity of Izumo.22 It was dissected out to determine which domain of Izumo protein is essential for its activity using circular dichroism, sedimentation equilibrium, and small-angle X-ray scattering procedures. It was found that an N-terminus fragment, designated Izumo putative functional fragment (IzumoPFF), is the functional domain of Izumo protein.23

Recently, three novel proteins (Izumo2, Izumo3, and Izumo4) have been found23 that share a local sequence similarity with the first discovered Izumo, described above, which has now been re-named as Izumo1. Among these, only Izumo4 has been shown to be expressed in testis as well as nonreproductive tissues. Others have sperm/testis-specific expression. Although no tests of orthology and paralogy have been conducted, these sequence comparisons across all Izumo genes indicate that all four Izumo genes have eight conserved cysteines residues within 144 amino acids with four α-helices. This gene region has been named the Izumo domain.24

Sub-cellular localization of Izumo1 on sperm cell

Izumo1 is not localized on the plasma membrane of mature sperm.19 Before fusing with eggs, sperm cell must undergo a physiological process called “capacitation” and a subsequent morphological change involving restructuring of the sperm membranes and release of the acrosomal contents, called the “acrosome reaction.”25 Izumo1 is found on the sperm plasma membrane, only of the acrosome-reacted sperm.21 However, the mechanisms and molecules involved in translocation of Izumo1 to plasma membrane during sperm–egg fusion have not been elucidated. Izumo1 shows a tendency to localize in the equatorial segment of the sperm surface after the acrosome reaction. This region is considered to initiate fusion with the oolemma.26

Rationale for using Izumo for CV development

The fertility field has virtually exploded with the advent of gene knockout technology. Almost every month there is a report on a new gene knockout that has some effect on fertility. At least 143 genes have been reported for females27,28 and 164 for males,29,30 whose knockout has some effect on fertility in mice. However, there are only a few genes whose knockout demonstrate specific effect on fertilization/fertility without a concomitant effect on some other non-reproductive function. Among the four major criteria required for CV development, the sperm-specificity and a vital role in fertilization/fertility are a must. Izumo protein fulfills almost all the criteria required for CV development, including sperm-specificity and a vital role in fertilization/fertility. Its knockout in male mice causes a total block of fertility without affecting sperm production, sperm motility, sperm capacitation/acrosome reaction, and binding to oocyte zona pellucida (ZP). Also, there is no effect on any other body cell/tissue and function. Izumo1 knockout sperm inhibit fertilization by not binding/fusing with the oocyte plasma membrane.21 Also, antibodies to mouse Izumo1 completely block binding/fusion of sperm with ZP-free mouse oocytes. This makes the Izumo protein an exciting sperm-specific molecule with a known structure–function relationship, and provides a strong rationale for examining its utility in CV development.

Studies on CV development using Izumo protein

Our laboratory was the first ever to examine the utility of Izumo protein in CV development.31,32 In one of these studies,32 various peptides based upon Izumo1 were synthesized and conjugated to various carrier proteins to provide T-cell help. Female mice were immunized with the peptide vaccines. Two different fertility trials with different doses of the peptide vaccines were conducted to examine the contraceptive effect. Injection of 150 µg of the peptide (Trial II) caused a better contraceptive effect than injection of 75 µg of the peptide vaccine (Trial I). When the antibodies against the peptides disappeared from circulation and genital tract after >9–10 months, all the animals regained fertility. These findings indicate the vaccination with Izumo peptides causes reversible contraception in female mice.

Subsequently, four studies have been published exploring Izumo1 as a contraceptive immunogen. Three of these studies confirmed our findings and reported a significant reduction in fertility of female mice after immunization with Izumo1 protein or cDNA.33–35 The fourth article36 concluded that immunization with Izumo1 does not cause a contraceptive effect in male and female mice. This study is flawed due to two reasons: (1) The authors used two groups of control mice for comparison with vaccinated male and female animals. Between the two control groups, there is a difference of 62.3% in litter size (mean ± SEM; 4.3 ± 0.5 vs. 6.9 ± 0.5, Table II in Ref. 36). With such a large difference between the two control groups, it is impossible to find a significant difference between the Izumo-vaccinated groups. (2) The authors used His6-tag recombinant Izumo1 protein for immunization. Recent studies have shown that the His6-tag can affect the efficacy of a vaccine.35 Antibodies against His6-tag recombinant Plasmodium falciparum MSP1 have lower percent parasite growth inhibition as compared with antibodies against tag-free recombinant protein. His6-tag affects structural stability and immunodominance of a protein.35,37

Table II.

Amino Acid Sequence of CDRs of Human YLP12 scFv Antibody Cloned from Immunoinfertile Men

| Light chain | Heavy chain | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| scFv antibody | CDR1 | CDR2 | CDR3 | CDR1 | CDR2 | CDR3 |

| YLP20 scFv | GFTVSSSA | VVYVDGTT | ARSNWHYVTAMYN | QSVTMNY | AAT | QQYGSSPPGVTF |

Modified from Samuel and Naz.72

Relevance to humans

Although mouse sperm proteins/genes can help us understand the molecular mechanisms involved in spermatogenesis and fertilization process, the challenge is to find its human counterpart with a function in human fertilization/fertility. Mouse sperm do not fertilize human eggs or vice versa, and there are several differences in spermatogenesis/fertilization and fertility between mouse and man. Of all the sperm proteins/genes which are being discovered and investigated in the mouse model, the real clinical utility of its human counterpart comes down to application in three areas: diagnosis and treatment of human cancer, infertility, and in non-steroidal, new generation contraceptive development for male and female, using pharmacologic or immunologic approaches.

Although many of the studies cannot be done directly in humans due to paucity of material (human sperm and oocyte) and ethical reason, the utility of an antigen in CV development can be investigated indirectly using sera and secretions (seminal plasma and cervical mucus) from immunoinfertile men and women. These men and women have ASA that are associated/causative factors of infertility. The presence of antibodies to a sperm antigen in immunoinfertile couples indicates: (1) sperm-specificity of the antigen, since these couples do not have any other disease concomitant with infertility, and (2) immunogenicity of the antigen in humans. Immunoinfertile men and women provide natural human models indicating how the CV will work. If an antigen is involved in human immunoinfertility, it makes it an exciting contraceptive vaccinogen.

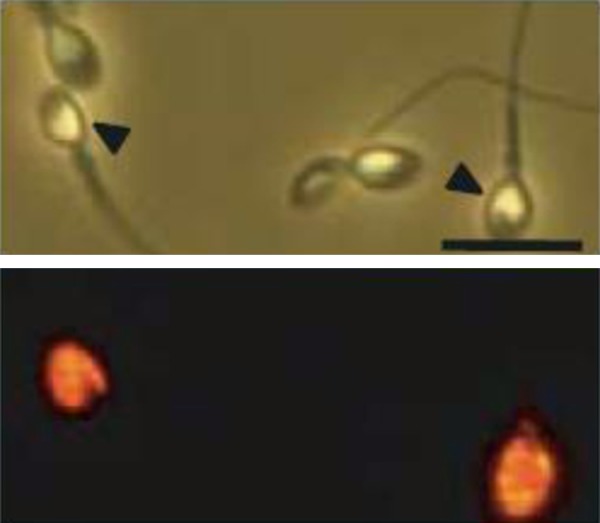

The cDNA sequence for human counterpart of mouse Izumo is available at NCBI (accession number BC034769). The antibodies to human Izumo bind to acrosome-reacted human sperm and react with a single band of approximately 37.2 kDa in membrane-solubilized human sperm extract in the Western blot procedure.21 Also, antibodies to human Izumo inhibit human sperm penetration into ZP-free hamster oocytes, an assay used for examining the fertilizing capacity of human sperm in infertility clinics. Similar to mouse sperm, the antibodies to human Izumo bind to acrosome-reacted, but not to acrosome-intact human sperm (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Immunolocalization of Izumo1 in human sperm. In the upper panel, there are four human sperm, two are acrosome-reacted (shown by arrowhead), and two have acrosome-intact. Izumo1 antibody reacts with only acrosome-reacted sperm and not with acrosome-intact sperm (lower panel). Modified with permission from Inoue et al.21

Recently, we conducted a study to examine if immunoinfertile men and women have antibodies against Izumo.38 Sera from immunoinfertile women (n = 25) and fertile women (n = 23), as well as sera from immunoinfertile men (n = 20) and fertile men (n = 15), were collected and analyzed for immunoreactivity with Izumo peptides in the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Three epitopes of human Izumo, namely one epitope of Izumo1, and two epitopes of Izumo2 [Izumo2 (K-15), and Izumo2 (T-17)], respectively, were selected for the present study.38 In the Western blot procedure, the Izumo1 antibody recognized a specific protein band of approximately 39 kDa in human sperm extract. In ELISA, 56% of the immunoinfertile female sera reacted positively with Izumo1, 40% with Izumo2 (K-15), and 20% with Izumo 2 (T-17) peptide. None of the sera (0%) from fertile women reacted positively with any of three Izumo peptides. None of the sera from immunoinfertile men (0%) or fertile men (0%) reacted positively with any of the three Izumo peptides. Our findings indicate that human sperm expresses Izumo protein, and the infertile but not fertile female sera have circulating antibodies against this protein. This is the first study ever which examined the presence and incidence of Izumo antibodies in female and male immunoinfertility. These findings will find clinical applications in specific diagnosis and treatment of infertility, and human CV development.38

The molecular and immunobiological characteristics of Izumo protein have been summarized in Table I.

Table I.

Molecular and Immunobiological Characteristics of Izumo Protein

| 1. Discovery | 2. Molecular parameters | 3. Utility in CV | 4. Human Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| • Discovered using OBF13 monoclonal antibody, and reactive protein was designated as Izumo (Izumo1) after Japanese shrine dedicated to marriage | • It is a sperm-specific 377 amino acid transmembrane glycoprotein with large extracellular region, a single transmembrane region, and a short cytoplasmic tail | • Sperm-specific; not expressed in somatic cells | • Human Izumo cDNA sequence is available at NCBIb |

| • Involvement in fertility | • Human sperm extract has Izumo protein band of ∼32.7 kDa | ||

| • Knockout mice have a total block of fertility due to sperm not binding/fusing with oolemma | • Infertile, and not fertile, women have antibodies to Izumo protein | ||

| • In mice, four Izumo proteins have been discovered having Izumo domain | • Izumo is a novel member of the immunoglobulin superfamily | • Antibodies to Izumo prevent sperm–oocyte membrane interaction | |

| • Izumo domain seems to be evolutionarily conserved among several mammalian species, including humans | • Although a glycoprotein, its functional activity resides in protein moiety | • Vaccination with Izumo peptide/cDNA causes a long-term, reversible contraceptive effect in mice | |

| • Protein domain involved in function is present in 319 amino acid extracellular region at N-terminus | |||

| • Mouse Izumo shows a protein band of ∼56 kDa in SDS-PAGEa | |||

| • Not present on sperm surface, but becomes accessible on surface after acrosome reaction |

SDS-PAGE, sodium-dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

NCBI, National Center for Biotechnology Information.

YLP12 Peptide Sequence

Human

Discovery and peptide science

The sperm surface is coated with carbohydrate-rich molecules that form a thick glycocalyx.39 N-Linked glycans, an important constituent of sperm glycocalyx, has an essential role in sperm–egg interaction.40,41 A recent study has shown that human sperm binding is mediated by the sialyl–Lewisx oligosaccharide moiety.42 N-Linked glycosylation is one of the most important post-translational modifications that regulates protein folding and mediates protein targeting, and cell–cell interaction.43 Over 90% of the cellular constituent glycoproteins have been annotated to the membrane, extracellular region, and lysosome. The exact nature of carbohydrate moieties involved in sperm-ZP interaction have not been delineated. Since the carbohydrate moieties are a poor immunogen, they per se cannot be used for CV development. Phage display technology can be used to delineate the peptide mimetic(s) of the carbohydrate moieties present on human sperm that is involved in binding to human ZP. These peptide mimetic(s) can then be used in CV development.

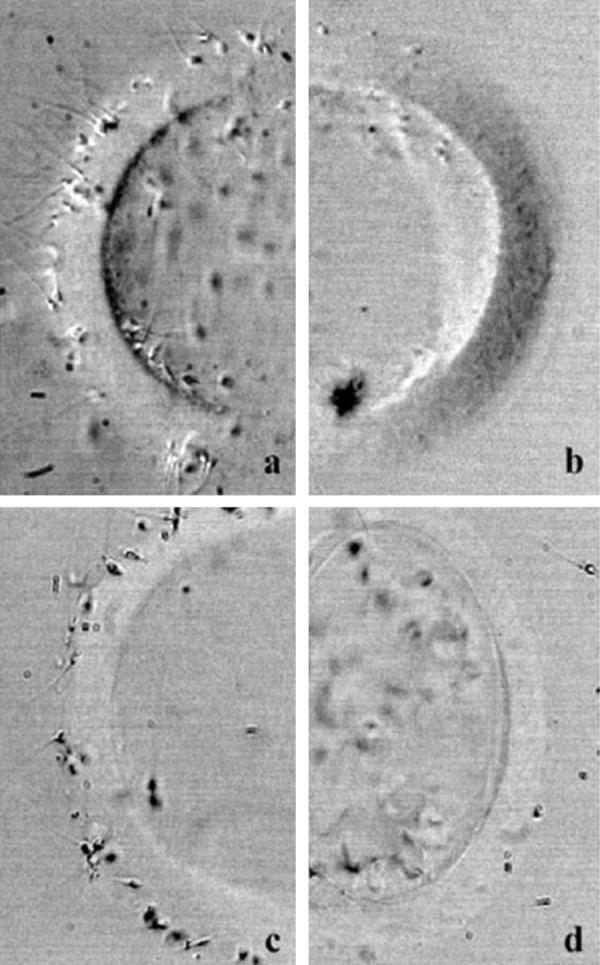

Our laboratory conducted a study to investigate the peptide mimetic(s) sequence(s) present on human sperm that is involved in recognition and binding to the complementary molecule of the human oocyte ZP.44 This was achieved by screening the FliTrx random phage display library (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA) that has an expression of 1.77 × 108 different 12-mer peptide sequences. A solubilized preparation of human oocyte ZP proteins was used as a probe. This procedure detected twelve clones with three different amino acid sequences designated as SNR12, GHR12, and YLP12, respectively, that reacted with ZP.44 Based upon these three sequences, a consensus sequence of 17 amino acid, designated as Consensus17, was obtained using the Lineup program. An extensive computer search in the sequence database including GenBank, National Biomedical Research Foundation (NBRF), and Swiss sequence banks did not reveal any known nucleotide/amino acid sequence having a complete identity/significant homology, indicating them to be novel sequences. Based on these sequences, four peptides, namely SNR12, GHR12, YLP12, and Consensus17, were synthesized and purified. Their ability to affect binding of human sperm with human ZP was examined using the hemizona assay.44 Only YLP12 and Consensus17 peptides significantly inhibited human sperm binding with human ZP. The effect on binding was concentration-dependent and specific. There was a greater inhibition with YLP12 peptide compared with Consensus17 peptide, so for further studies YLP12 peptide was selected (Fig. 2). The dodecamer YLP12 has the following amino acid sequence: YLPVGGLRRIGG. YLP12 peptide was conjugated to tetanus toxoid (TT) to provide T-cell carrier help to raise polyclonal antibodies in female rabbits. YLP12 antibodies also inhibited sperm–zona binding.

Figure 2.

Effect of YLP12 peptide and its antibodies on human sperm–human oocyte zona pellucida (hoZP) in the hemizona assay. In the hemizona assay, the human oocyte is cut into two equal halves, with one half treated with the peptide/antibodies and the second half serving as control. YLP12 peptide caused inhibition of sperm binding to hoZP (b). The control half from the same oocyte, not treated with the peptide, demonstrated binding to sperm (a). Treatment of YLP12 antibodies also inhibited sperm binding to hoZP (d), while control half showed binding to sperm (c).Reproduced from Naz et al.44

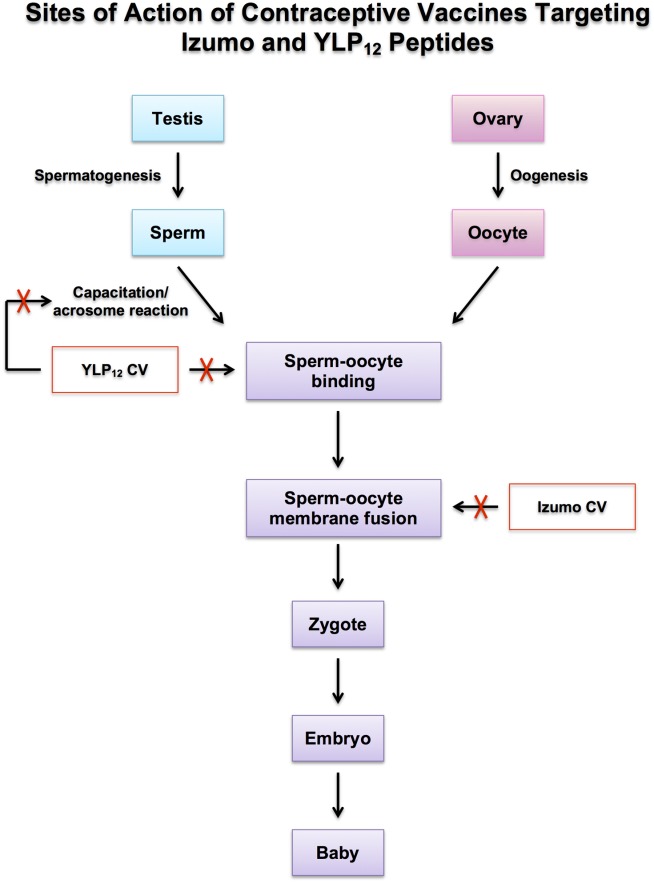

Figure 3.

Schematic model indicating the sites at which the vaccination against Izumo and YLP12 peptides will block fertilization cascade causing contraception. Injection of YLP12 vaccine will raise sperm-specific antibodies which will block sperm capacitation/acrosome reaction and sperm–oocyte ZP binding. Injection of Izumo vaccine will induce sperm-specific antibodies which will block sperm–oocyte membrane fusion.

Western blot and immunoprecipitation procedures were performed to examine the component of the human ZP that reacted with the YPL12 peptide. In both these assays, YLP12 peptide specifically reacted with the ZP3 component of human ZP.44 YLP12 antibodies specifically recognized a protein band of approximately 72 ± 5 kDa only in the testis lane in the Western blot procedure involving solubilized extracts of ten different human tissues. These findings indicate that YLP12 sequence is tissue/cell-specific in humans.

Sub-cellular localization of YLP12 on sperm cell

The monoclonal antibody was raised against YLP12 peptide using hybridoma technology.45 The authenticity of the clone was confirmed by specific binding of the antibody with YLP12 peptide. Both monoclonal as well as polyclonal antibodies against YLP12 peptide reacted with acrosome, mid-piece, and tail regions of human and mouse sperm in the immunofluorescence and electromicroscopic techniques. These findings indicate that the YLP12 sequence is present on acrosome, mid-piece, and tail regions of sperm cell.

Relevance of the YLP12 peptide to human immunoinfertility

Sera (n = 15) and seminal plasma (n = 30) from ASA-positive immunoinfertile men (n = 45) and antibody-negative fertile men (n = 45), were tested for immunoreactivity with synthetic YLP12 peptide using ELISA.46 Of the immunoinfertile sera tested, 73% were positive for IgG, and 40% for IgA class of antibodies. Of the immunoinfertile seminal plasma tested, 20% were positive for IgG, and 43% for IgA. None of the sera or seminal plasma from fertile men showed a positive reactivity.

Sera from immunoinfertile (n = 67) and fertile (n = 19) women were also tested for immunoreactivity with YLP12 peptide.47 Forty-three percent of the immunoinfertile sera, and none of the fertile sera, reacted with YLP12 peptide.

These findings from both infertile men and women indicate that YLP12 sequence is: (a) immunogenic in humans and can raise both circulating and local antibodies, (b) sperm-specific, and (c) involved/associated with human infertility.

Studies on CV development using YLP12 peptide

Peptide vaccination

To examine the contraceptive efficacy of YLP12 peptide, a vaccine was prepared by conjugating synthetic YLP12 peptide with binding subunit of recombinant cholera toxin (rCTB).48 Female virgin mice were vaccinated with YLP12-rCTB vaccine via intranasal (in), intramuscular (im) or in/im combined routes. rCTB has been successfully used as a carrier protein and as an adjuvant for enhancing circulating mucosal IgA and systemic IgG antibody response of a vaccine. Vaccination of female mice with YLP12-rCTB by various routes induced a contraceptive state resulting in a significant reduction in litter size. Animals having high antibody titers showed a complete block. Vaccination via all routes inhibited fertility, with im immunization showing the greatest reduction. Vaccination via im route caused an overall 71% reduction in litter size, in route caused a 62% reduction, and in/im combined routes caused a 63% reduction in fertility. Antibody reactivity correlated significantly with reduction in fertility, with vaginal IgA titers showing the highest degree of correlation.

Antibodies raised against YLP12 peptide were sperm/testis-specific and recognized a protein band of 72 ± 2 kDa in testis extract and a band of 50 ± 2 kDa in sperm extract. These specific bands were not observed in the protein extracts of ten mouse somatic tissues tested in the western blot procedure.

Involuntary reversibility of contraceptive effect

Animals showing the highest antibody titers and greatest contraceptive effect were kept to examine the reversibility of the contraceptive effect.48 Antibody reactivity was monitored biweekly. With time, the antibody titers started decreasing and by days 305–322 post-vaccination, the antibodies completely disappeared from serum and vaginal washings. The antibody-free animals regained fertility and delivered a normal litter size having healthy babies.48

Voluntary reversibility of contraceptive effect at any desired time

It was investigated whether one could voluntarily and willingly reverse the contraceptive effect at a particular time if one wants to conceive before the effect of the vaccine subsides.48 Normally the fertility is regained involuntarily after the antibodies disappear, which takes 305–322 days. The synthetic YLP12 peptide, per se without conjugation to rCTB, was administered in mice that had previously been vaccinated and were in contraceptive state. The administration of peptide by intravenous or intravaginal route caused a regain of fertility, with the intravaginal administration resulting in a complete reversal. Intravenous or intravaginal administration of the peptide in control animals did not affect fertility.48 Peptide administration by either route did not cause a booster effect on the antibody titers in either vaccinated or control groups. This could be expected because the peptide is 12-mer, probably lacking a T cell epitope, and thus too small to raise an antibody response without conjugation to a T cell carrier, namely rCTB. It appears that peptide administration transiently bioneutralizes the antibodies, which frees the sperm to fertilize egg.

The contraceptive efficacy of YLP12 peptide, as reported by us earlier, was subsequently confirmed independently by another group of investigators.49 Vaccination of FvB/cJ female mice with Johnson grass mosaic virus-like particles containing YLP12 peptide induced a contraceptive effect.

DNA vaccination

All the above studies used the peptide vaccine approach for CV development. DNA vaccines have been proposed as viable alternatives to peptide vaccines, and have several distinct advantages including easy manipulation, use of a generic technology, simplicity of manufacture, and chemical and biology stability.50–53 DNA vaccines generally enhance Th1 immune response resulting in secretion of cytokines that negatively affect gamete and embryo function.54–56

In view of the above findings, we conducted a study to examine if DNA vaccine can enhance the efficacy of CV based upon YLP12 sequence. The contraceptive effect of YLP12 DNA vaccine was examined.57 YLP12 36 bp cDNA was cloned into pVAX1 vector to prepare the DNA vaccine. Two additional vaccine constructs were made by in frame cloning of one and two CpG repeats in the YLP12-cDNA vaccine. Five groups of female mice were immunized intradermally by using gene gun with YLP12-cDNA, YLP12-cDNA-CpG, YLP12-cDNA-CpG-CpG, YLP12-cDNA mixed with exogenous synthetic CpG oligodeoxynucleotide (ODN), or vector DNA alone, respectively. Vaccination with all three YLP12 constructs and the YLP12 vaccine mixed with exogenous ODN induced an antibody response both in sera as well as locally in the vaginal tract. Immunization with all constructs and formulation caused a significant reduction in fertility of female mice. The highest reductions were seen in the group immunized with YLP12-cDNA-CpG-CpG (two repeats) and in the group immunized with YLP12 vaccine administered with exogenous CpG ODN. Expression of both Th1 cytokines (IL-2 and IFN-γ) and Th2 cytokines (IL-4 and IL-10) was enhanced after DNA vaccination as compared with controls, with a bias toward Th1 response. The contraceptive effect was seen up to 1.3 years of the observation period. These novel findings indicate that the intradermal immunization with a sperm-specific DNA vaccine causes a long-term circulating and local immune response resulting in contraception in female mice.

The mechanism(s) by which antibodies to YLP12 cause contraception is primarily by inhibiting sperm–oocyte ZP binding and penetration, resulting in failure of fertilization. YLP12 antibodies do not inhibit sperm motility. However, besides inhibiting sperm–oocyte ZP fertilization, YLP12 antibodies also inhibit sperm (both human and murine) capacitation and acrosome reaction.45,48

Isolation of human YLP12 single-chain variable fragment (scFv) antibody from immunoinfertile men

Besides immunization with CV to induce antibody response, the passive immunization using the preformed antibodies can provide an alternative approach to contraception. The antibody therapies have been found to be successful against various infectious diseases, both in animals and humans. Some of the antibodies have become treatment modalities in the clinics.58–61 Phage display technology62 has been widely used to obtain a variety of engineered antibodies, including scFv antibodies against several antigens.63–67 scFv is an antibody fragment that plays a major role in the antigen-binding activity, and is composed of variable heavy (VH) and variable light (VL) chains connected by a peptide linker. The most widely used peptide linker is a repeat of a 15-residue sequence of glycine and serine (Gly4Ser)3. This linker provides a flexibility to move approximately 35–40°A between the carboxyl terminal of VH and the amino terminus of VL chains for efficient antibody binding. Also, the linker length promotes more intra-domain than inter-domain disulfide bonding between VH and VL chains. The affinity and stability of scFv antibodies produced in bacteria are comparable with those of the native antibodies. These antibodies can be produced on large scale using specially modified bacterial hosts and have an advantage over the whole immunoglobulin (Ig) molecule. ScFv antibodies lack the Fc portion which obliterates unwanted secondary effects associated with Fc, and due to its small size can be easily absorbed into tissues and gene manipulated.68

If administered into humans, the mouse monoclonal antibody can elicit strong anti-mouse antibody reaction, and the chimeric antibody can cause anti-chimeric response against murine antibody variable regions.69–71 The xenogenic complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) of humanized antibodies can also evoke an anti-idiotypic response. Thus, the antibodies have to be of human origin if to be used in humans. The potential poor immunogenicity and toxicity of an antigen, and ethical issues, limit immunizing humans to obtain human antibodies. However, the phage display technology can be employed to obtain human antibodies against target antigens if they exist involuntarily in humans, such as ASA in immunoinfertile men and women, and vasectomized men. Since immunoinfertile/vasectomized men have antibodies to YLP12 peptide, we used their leukocytes to obtain human YLP12 scFv antibodies from them.72

Peripheral blood leukocytes (PBL) from ASA-positive immunoinfertile and vasectomized men were activated with human sperm antigens in vitro, and the complementary DNA prepared and PCR-amplified using primers based on all the variable regions of heavy and light chains of immunoglobulins.72 The scFv repertoire was cloned into pCANTAB5E vector to create a human scFv antibody library. Panning of the library against sperm specific antigens yielded several clones, and the four strongest reactive were selected for further analysis. These clones had novel sequences with unique CDRs.72 ScFv antibodies were expressed, purified, and analyzed for human sperm reactivity and effect on human sperm function. Three of these scFv antibodies reacted with other sperm antigens, and one with YLP12 peptide. This clone was designated as YLP20 and inhibited human sperm function as monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies to YLP12. This is the first study ever to delineate a human scFv antibody to a defined sperm antigen. The CDRs sequences of YLP20 human scFv antibody to YLP12 is shown in Table II.

The molecular and immunobiological characteristics of YLP12 peptide have been summarized in Table III.

Table III.

Molecular and Immunobiological Characteristics of YLP12 peptide

| 1. Discovery | 2. Molecular parameters | 3. Utility in CV | 4. Human application | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| • Carbohydrate moieties on human sperm are essential in sperm–egg interaction, but difficult to characterize and are not immunogenic | • It is a dodecamer with amino acid sequence: YLPVGGLRRIGG | • Vaccination via intranasal/intramuscular route with YLP12 peptide causes long-term, reversible contraception, without any side effect, in female mice | • Infertile, but not fertile, men have YLP12 antibodies in sera and seminal plasma. Infertile, but not fertile, women have YLP12 antibodies in sera | |

| • Peptide mimetic sequences of these carbohydrate moieties can be delineated using phage display technology | • Present on acrosome, mid-piece, tail regions of sperm cell | |||

| • Sperm-specific peptide, reacts with ZP3 component of human oocyte ZP, and not with any other human cell/tissue | • Intradermal vaccination of female mice with YLP12 DNA also causes long-lasting contraception | • Above findings indicate that YLP12 is immunogenic, sperm-specific, and can raise circulating/local antibodies, which are involved/associated with infertility | ||

| • Using solubilized human oocyte ZP proteins as a probe, we investigated peptide mimetic sequences present on human sperm | • YLP12 antibodies inhibit human sperm–human oocyte ZP binding | • Contraceptive effect reversed involuntarily when antibodies disappear by day 305–322 post-vaccination | • A human scFv antibody has been isolated, cloned, and sequenced from infertile men. This human YLP12 scFv antibody can provide novel immunocontraceptive, first of its kind | |

| • Contraceptive effect can also be reversed voluntarily at any desired time by administration of YLP12 peptide to neutralize antibodies | ||||

| • YLP12 dodecamer sequence, a peptide mimetic, was discovered which showed the strongest binding with human oocyte ZP | ||||

| • Synthetic YLP12 peptide inhibits human sperm binding with human oocyte ZP |

ZP, zona pellucida.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the data indicates that Izumo protein and YLP12 peptide are sperm-specific molecules that are excellent candidates for CV development. Development of CV is somewhat uniquely challenging because, unlike other vaccines, CV have to be used by healthy individuals and require close to 100% efficacy. CV should be free of side effects, thus only sperm-specific molecules can be used for antisperm CV development. Besides using the tissue-specific targets, development of CV requires vaccines that can induce high titer, long-lasting, reversible antibody response. The inter-individual variation in immune response after vaccination is another concern. This issue can be overcome by the passive antibody administration approach. For YLP12 peptide, we have cloned human scFv antibody that can be used for development of novel passive immunocontraceptive, first of its kind. At this time, there is no CV or immunocontraceptive available in the market for human use, although CV have been successfully developed to control farm, feral, stray, and domestic animal populations.14 Recent advances in the fields of vaccinology, adjuvants, and nanotechnology will help to expedite CV development. In the WHO meeting on Contraception in Geneva, Switzerland, November 13–14, 2012, development of CV was enlisted as one of the highest priorities. An International Task-Force has been set for CV development. Development of single-shot, reversible CV will be a significant advancement in the field of contraception. It appears that Izumo and YLP12 can provide suitable candidates for CV development. Additional studies are needed on the structure-function relationship of Izumo and YLP12 peptides, which will help to delineate the molecular mechanisms related to their role in fertilization cascade, and development of better vaccine strategies. The protein science technology will be helpful in these aspects. The present focus is on enhancing the immunogenicity of the CV based upon Izumo and YLP12 peptides.

Acknowledgments

More than 250 persons, including undergraduate, graduate and medical students, post-doctoral fellows, residents, and faculty have worked in the lab during the last three decades on various aspects of the contraceptive vaccine development. The authors sincerely thank all of them. Also, the projects on contraceptive vaccines have been funded by local, state, private, and federal agencies over the last three decades, which is gratefully acknowledged. The authors are also thankful to Morgan Lough, Clara Beth Novotny, and Lepha Logue for help in writing this review. The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.World POPClock Projection. US Census Bureau. Available at http://www.census.gov/popclock/ (Accessed: 02 January 2014)

- 2.Henshaw SK. Unintended pregnancy in the United States. Fam Plann Perspect. 1998;30:24–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trussell J. Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception. 2004;70:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. WHO/63 News Release, November 1, 2006. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/press_release/2006/PR_63.pdf (Accessed: 05 January 2014)

- 5.Liskin L, Pile JM, Quillan WF. Vasectomy safe and simple. Popul Rep. 1983;4:61–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krause WKH, Naz RK, editors. Immune infertility. Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 2009. pp. 1–236. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allardyce RA. Effect of ingested sperm on fecundity in the rat. J Exp Med. 1984;159:1548–1553. doi: 10.1084/jem.159.5.1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards RG. Immunological control of fertility in female mice. Nature. 1964;203:50–53. doi: 10.1038/203050a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Menge AC. Immune reactions and infertility. J Reprod Fertil Suppl. 1970;10:171–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baskin MJ. Temporary sterilization by injection of human spermatozoa: a preliminary report. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1932;24:892–897. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mancini RE, Andrana JA, Saraceni D, Bachmann AE, Lavieri JCM, Nemirovsky M. Immunological and testicular response in men sensitized with human testicular homogenate. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1965;25:859–875. doi: 10.1210/jcem-25-7-859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naz RK. Vaccine for contraception targeting sperm. Immunol Rev. 1999;171:193–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1999.tb01349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naz RK. Antisperm contraceptive vaccines: where we are and where are we going? Am J Reprod Immunol. 2011;66:5–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2011.01000.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naz RK. Recent progress toward development of vaccines against conception. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2014;13:145–154. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2014.869420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nature. Web Focus: The Mouse Genome. Nature Publishing Group; 2003. http://www.nature.com/nature/mousegenome/ (Accessed: 06 January 2014) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Genome Sizes. Table of Genome Sizes. http://Users.rcn.com; 2013. http://users.rcn.com/jkimball.ma.ultranet/BiologyPages/G/GenomeSizes.html (Accessed: 06 January 2014)

- 17.Pertea M, Salzberg SL. Between a chicken and a grape: estimating the number of human genes. Genome Biol. 2010;11:206. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-5-206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stein KK, Go JC, Lane WS, Primakoff P, Myles DG. Proteomic analysis of sperm regions that mediate sperm-egg interactions. Proteomics. 2006;6:3533–3543. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okabe M, Adachi T, Takada K, Oda H, Yagasaki M, Kohama Y, Mimura T. Capacitation-related changes in antigen distribution on mouse sperm heads and its relation to fertilization rate in vitro. J Reprod Immunol. 1987;11:91–100. doi: 10.1016/0165-0378(87)90014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okabe M, Yagasaki M, Oda J, Matzno S, Kohama Y, Mimura T. Effect of a monoclonal anti-mouse sperm antibody (OBF13) on the interaction of mouse sperm with zona-free mouse and hamster eggs. J Reprod Immunol. 1988;13:211–219. doi: 10.1016/0165-0378(88)90002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inoue N, Ikawa M, Isotani A, Okabe M. The immunoglobulin superfamily protein Izumo is required for sperm to fuse with eggs. Nature. 2005;434:234–238. doi: 10.1038/nature03362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inoue N, Ikawa M, Okabe M. Putative sperm fusion protein Izumo and the role of N-glycosylation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;377:910–914. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.10.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inoue M, Hamada D, Kamikubo H, Hirata K, Kataoka M, Yamamoto M, Ikawa M, Okabe M, Hagihara Y. Molecular dissection of Izumo1, a sperm protein essential for sperm-egg fusion. Development. 2013;140:3221–3229. doi: 10.1242/dev.094854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grayson P, Civetta A. Positive selection and the evolution of Izumo genes in mammals. Int J Evol Biol. 2012;7:958164. doi: 10.1155/2012/958164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yanagimachi R. Mammalian fertilization. In: Knobil N, Neil JD, editors. The physiology of reproduction. 2nd edn. New York: Raven Press; 1994. pp. 189–317. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Satouh Y, Inuoe N, Ikawa M, Okabe M. Visualization of the moment of mouse sperm-egg fusion and dynamic localization of Izumo1. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:4985–4990. doi: 10.1242/jcs.100867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naz RK, Rajesh C. Gene knockouts that cause female infertility: search for novel contraceptive targets. Front Biosci. 2005;10:2447–2459. doi: 10.2741/1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naz RK, Catalano B. Gene knockouts that affect female fertility: novel targets for contraception. Front Biosci. 2010;S2:1092–1112. doi: 10.2741/s120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naz RK, Rajesh P. Novel testis/sperm-specific contraceptive targets identified using gene knockout studies. Front Biosci. 2005;10:2430–2446. doi: 10.2741/1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naz RK, Engle A, None R. Gene knockouts that affect male fertility: novel targets for contraception. Front Biosci. 2009;14:3994–4007. doi: 10.2741/3507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naz RK, Aleem A. Effect of immunization with six sperm peptide vaccines on fertility of female mice. Soc Reprod Fertil Suppl. 2007;63:455–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Naz RK. Immunocontraceptive effect of Izumo and enhancement by combination vaccination. Mol Reprod Dev. 2008;75:336–344. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.An G, Huang TH, Wang DG, Xie QD, Ma L, Chen DY. In vitro and in vivo studies evaluating recombinant plasmid pCXN2-mIzumo as a potential immunocontraceptive antigen. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2009;61:227–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2009.00685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang M, Lv Z, Shi J, Hu Y, Xu C. Immunocontraceptive potential of the Ig-like domain of Izumo. Mol Reprod Dev. 2009;76:794–801. doi: 10.1002/mrd.21027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shrestha A, Wadhwa N, Gupta SK. Evaluation of recombination fusion protein comprising dog zona pellucida glycoprotein-3 and Izumo and individual fragments as immunogens for contraception. Vaccine. 2014;32:546–571. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.11.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang DG, Huang TH, Xie QD, An G. Investigation of recombinant mouse sperm protein Izumo as a potential immunocontraceptive antigen. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2008;59:225–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2007.00571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khan F, Legler PM, Mease RM, Duncan EH, Bergmann-Leitner ES, Angov E. Histidine affinity tags affect MSP1(42) structural stability and immunodominance in mice. Biotechnol J. 2012;7:133–147. doi: 10.1002/biot.201100331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clark S, Naz RK. Presence and incidence of Izumo antibodies in sera of immunoinfertile women and men. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2013;69:256–263. doi: 10.1111/aji.12060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schoter S, Osterhoff C, McArdle W, Ivell R. The glycocalyx of the sperm surface. Hum Reprod Update. 1999;5:302–313. doi: 10.1093/humupd/5.4.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Benoff S. Carbohydrates and fertilization: an overview. Mol Hum Reprod. 1997;3:599–637. doi: 10.1093/molehr/3.7.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang G, Wu Y, Zhou T, Guo Y, Zheng B, Wang J, Bi Y, Liu F, Zhou Z, Guo X, Sha J. Mapping of the N-linked glycoproteome of human spermatozoa. J Proteome Res. 2013;12:5750–5759. doi: 10.1021/pr400753f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pang PC, Chiu PC, Lee CL, Chang LY, Panico M, Morris HR, Haslam SM, Khoo KH, Clark GF, Yeung WS, Dell A. Human sperm binding is mediated by the sialyl-Lewisx oligosaccharide on the zona pellucida. Science. 2011;333:1761–1764. doi: 10.1126/science.1207438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Varki A. Biological roles of oligosaccharides: all of the theories are correct. Glycobiology. 1993;3:97–130. doi: 10.1093/glycob/3.2.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Naz RK, Zhu X, Kadam AL. Identification of human sperm peptide sequence involved in egg binding for immunocontraception. Biol Reprod. 2000;62:318–324. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod62.2.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Naz RK, Chauhan SC, Trivedi RN. Monoclonal antibody against human sperm-specific YLP12 peptide sequence involved in oocyte binding. Arch Androl. 2002;48:169–175. doi: 10.1080/01485010252869243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Naz RK, Chauhan SC. Presence of antibodies to sperm YLP12 synthetic peptide in sera and seminal plasma of immunoinfertile men. Mol Hum Reprod. 2001;7:21–26. doi: 10.1093/molehr/7.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Williams J, Samuel A, Naz RK. Presence of antisperm antibodies reactive with peptide epitopes of FA-1 and YLP12 in sera of immunoinfertile women. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2008;59:518–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2008.00581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Naz RK, Chauhan SC. Human sperm-specific peptide vaccine that causes long-term reversible contraception. Biol Reprod. 2002;67:674–680. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod67.2.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Choudhury S, Kakkar V, Suman P, Chakrabarti K, Vrati S, Gupta SK. Immunogenicity of zona pellucida glycoprotein-3 and spermatozoa YLP12 peptides presented on Johnson grass mosaic virus-like particles. Vaccine. 2009;27:2948–2953. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu MA. DNA vaccines: a review. J Intern Med. 2003;253:402–410. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Patil SD, Rhodes DG, Burgess DJ. DNA-based therapeutics and DNA delivery system: a comprehensive review. AAPS J. 2005;7:E61–E77. doi: 10.1208/aapsj070109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Coban C, Kobiyama K, Jounai N, Tozuka M, Ishii KJ. DNA vaccines: a simple DNA sensing matter? Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9:2216–2221. doi: 10.4161/hv.25893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Flingai S, Czerwonko M, Goodman J, Kudchodkar SB, Muthumani K, Weiner DB. Synthetic DNA vaccines: improved vaccine potency by electroporation and co-delivered genetic adjuvants. Front Immunol. 2013;4:354. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Naz RK, Mehta K. Cell-mediated immune responses to sperm antigens: effects on mouse sperm and embryos. Biol Reprod. 1989;41:533–542. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod41.3.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Naz RK, Kumar R. Transforming growth factor beta1 enhances expression of 50 kDa protein related to 2′-5′ oligoadenylate synthetase in human sperm cells. J Cell Physiol. 1991;146:156–163. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041460120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Naz RK, Zhu X, Kadam AL. Identification of human sperm peptide sequence involved in egg binding for immunocontraception. Biol Reprod. 2000;62:318–324. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod62.2.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Naz RK. Effect of sperm DNA vaccine on fertility of female mice. Mol Reprod Dev. 2006;73:918–928. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Riethmüller G, Schneider-Gädicke E, Johnson MP. Monoclonal antibodies in cancer therapy. Curr Opin Immunol. 1993;5:732–739. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(93)90129-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Casadevall A. Passive antibody therapies: progress and continuing challenges. Clin Immunol. 1999;93:5–15. doi: 10.1006/clim.1999.4768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dunman PM, Nesin M. Passive immunization as prophylaxis: when and where will this work? Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2003;3:486–496. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2003.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sliwkowski MX, Mellman I. Antibody therapeutics in cancer. Science. 2013;341:1192–1198. doi: 10.1126/science.1241145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Smith GP. Filamentous fusion phage: novel expression vectors that display cloned antigens on the virion surface. Science. 1985;228:1315–1317. doi: 10.1126/science.4001944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rader C, Barbas CF., III Phage display of combinatorial antibody libraries. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1997;8:503–508. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(97)80075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ye Z, Hellstrom I, Hayden-Ledbetter M, Dahlin A, Ledbetter JA, Hellstrom KE. Gene therapy for cancer using single-chain Fv fragments specific for 4-1BB. Nat Med. 2002;8:343–348. doi: 10.1038/nm0402-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Park KJ, Lee SH, Kim TI, Lee HW, Lee CH, Kim EH, Jang JY, Choi KS, Kwon MH, Kim YS. A human ScFv antibody against TRAIL receptor 2 induces autophagic cell death in both TRAIL-sensitive and TRAIL-resistant cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7327–7334. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang W, Matsumoto-Takasaki A, Kusada Y, Sakaue H, Sakai K, Nakata M, Fujita-Yamaguchi Y. Isolation and characterization of phage-displayed single chain antibodies recognizing nonreducing terminal mannose residues. 2. Expression, purification, and characterization of recombinant single chain antibodies. Biochemistry. 2007;46:263–270. doi: 10.1021/bi0618767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhou Y, Drummond DC, Zou H, Hayes ME, Adams GP, Kirpotin DB, Marks JD. Impact of single-chain Fv antibody fragment affinity on nanoparticle targeting of epidermal growth factor receptor expressing tumor cells. J Mol Biol. 2007;371:934–947. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yokota T, Milenic DE, Whitlow M, Schlom J. Rapid tumor penetration of a single-chain Fv and comparison with other immunoglobulin forms. Cancer Res. 1992;52:3402–3408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Koren E, Zuckerman LA, Mire-Sluis AR. Immune responses to therapeutic proteins in humans-clinical significance, assessment and predicition. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2002;3:349–360. doi: 10.2174/1389201023378175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mirick GR, Bradt BM, Denardo SJ, Denardo GL. A review of human anti-globulin antibody (HAGA, HAMA, HACA, HAHA) responses to monoclonal antibodies. Not four letter words. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004;48:251–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sidhu SS, Fellouse FA. Synthetic therapeutic antibodies. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:682–688. doi: 10.1038/nchembio843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Samuel AS, Naz RK. Isolation of human single chain variable fragment antibodies against specific sperm antigens for immunocontraceptive development. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:1324–1337. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]