Abstract

The KIX domain is a mediator of the interaction between different transcription factors. This complex function is carried out via two distinct binding sites located on opposite sides of the protein; namely, the ‘c-Myb site’ and the ‘MLL site’, named after their characteristic ligands—the transactivation domain of c-Myb and the mixed lineage leukemia protein (MLL). Both these ligands are unstructured in isolation and fold only upon binding, posing the KIX domain as an ideal candidate to explore the binding induced folding reaction of intrinsically unstructured proteins. Here, we complement the recent kinetic description on the interaction between KIX and c-Myb, by characterizing the binding kinetics between KIX and MLL, at different pH and ionic strength conditions. Furthermore, we analyze quantitatively the mechanism of allosteric communication between the topologically distinct c-Myb and MLL sites. The implications of our results are discussed in the light of previous work on other intrinsically unstructured systems.

Keywords: kinetics, reaction mechanism, intrinsically disordered proteins, folding upon binding

Introduction

Regulation of the gene expression is a key feature for the maintenance and the conservation of cellular physiology. Transcriptional activation is a critical passage in the regulation of gene expression involving an intricate network of different proteins, which mediate the interaction between DNA and the RNA polymerase.1 One of the proteins that has a key crucial role in this network of protein–protein interactions is CBP (cAMP-response element binding protein (CREB)-binding protein), a large multidomain oligomer containing intrinsically disordered regions and folded domains that can interact with many different transcription factors.2,3 Among them, a globular domain, named “KIX”, is the principal mediator of these interactions.4,5 The three-dimensional structure of KIX, comprising three α-helices and two short 310-helices, reveals two topologically distinct binding sites that can interact with many transcription factors and are located on opposite sides of the domain.6 These two distinct binding sites are named after two characteristic ligands: the c-Myb site, after the transactivation domain of the oncoprotein c-Myb, and the MLL site, after the mixed lineage leukemia protein.7

The transactivation domain of c-Myb is largely unstructured before binding and folds into an amphipathic helix only when bound to KIX.8 We recently characterized using stopped-flow and temperature-jump the mechanism of recognition and interaction between KIX and c-Myb, showing that this intrinsically disordered protein (IDP) folds upon binding to its partner via a folding-after-binding scenario.9 In fact, we found that 1,1,1-tri-fluoro-ethanol (which stabilizes the helical conformation of c-Myb) had a negligible effect on the association rate constant, yet stabilized the complex by lowering the dissociation rate constant, suggesting that binding precedes folding. Furthermore, we have unveiled by Φ value analysis,10 the structural features of the transition state for the binding-induced folding reaction of c-Myb to KIX11 showing that recognition between KIX and c-Myb is characterized by a remarkable geometrical precision and by the formation of a surprisingly ordered transition state.

The MLL gene is usually disrupted by chromosomal translocations in childhood leukemias and in therapy-induced acute myeloid leukemias.12 MLL, which is crucial for production of normal blood cells, is a homologue of the Drosophila trithorax (Trx), and is involved in maintenance of homeobox (Hox) gene expression during early embryogenesis. MLL fusion proteins caused by chromosomal translocations usually loose the activation domain that mediates the interaction with KIX.13 The binding of MLL to KIX is direct and it was shown to be necessary for the MLL-mediated transcriptional activation. In vitro experiments showed that complex formation between the activation domain of MLL and KIX allosterically enhances the interaction with the transactivation domain of c-Myb.7,14 The structure of the ternary complex between c-Myb:KIX:MLL has been solved by Wright and co-workers6 and is reported in Figure 1.

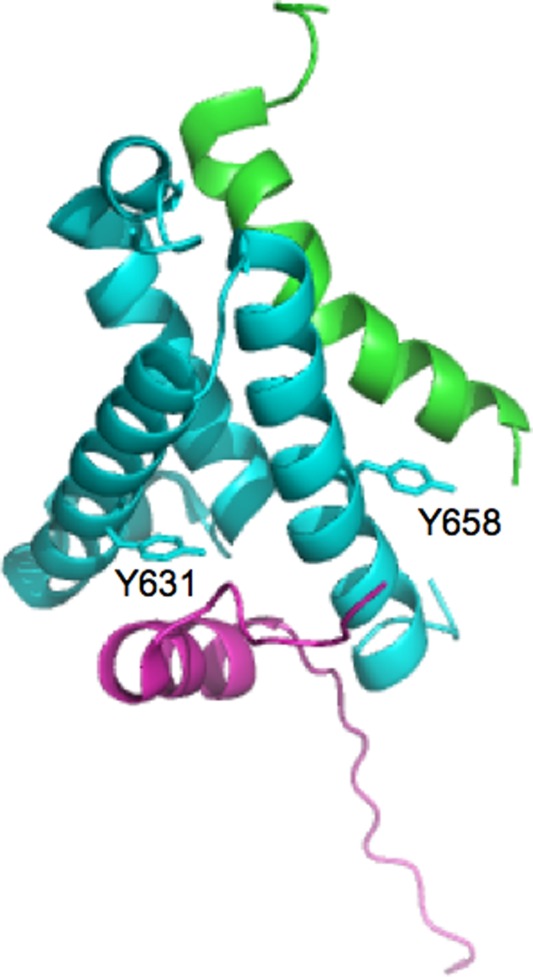

Figure 1.

Three-dimensional structure of the ternary complex between KIX (light blue), c-Myb (green), and MLL (purple). Residues Y631 and Y658 of KIX, which were mutated into W to engineer a fruorophore sensitive to the binding of either MLL or c-Myb, respectively, are highlighted in sticks.

Here we characterize the binding mechanism between KIX and the activation domain of MLL, using stopped-flow experiments carried out under different experimental conditions (i.e., pH and ionic strength). Furthermore, by performing kinetic experiments on the recognition between the binary MLL:KIX complex and c-Myb, we analyze quantitatively the mechanism of allosteric communication between the MLL and the c-Myb sites of KIX.

Results

To follow the mechanism of binding and recognition between KIX and MLL, we first engineered a construct displaying a fluorescence change upon complex formation. In fact, the KIX domain contains a tryptophan at position 591, which being located far from the MLL binding pocket does not display any detectable fluorescence signal change upon binding. Thus, we designed a pseudo-wild-type Y631W variant containing a tryptophan residue in the proximity of the MLL binding site. The equilibrium binding transition of MLL to KIX Y631W, monitored by fluorescence at pH 7.2 in the presence of 150 mM KCl and 10°C, is reported in Figure 2(A). The observed transition is consistent with a simple hyperbolic behavior, returning an apparent KD of 1.0 ± 0.1 µM. By considering the differences in temperature (10 vs. 25°C) and experimental methodology (fluorescence titration vs. isothermal calorimetry), the observed KD is not inconsistent with the value of 2 µM previously reported by Wright and co-workers;7 indicating that substitution of tyrosine 631 with a tryptophan has little effect on the affinity between MLL and KIX.

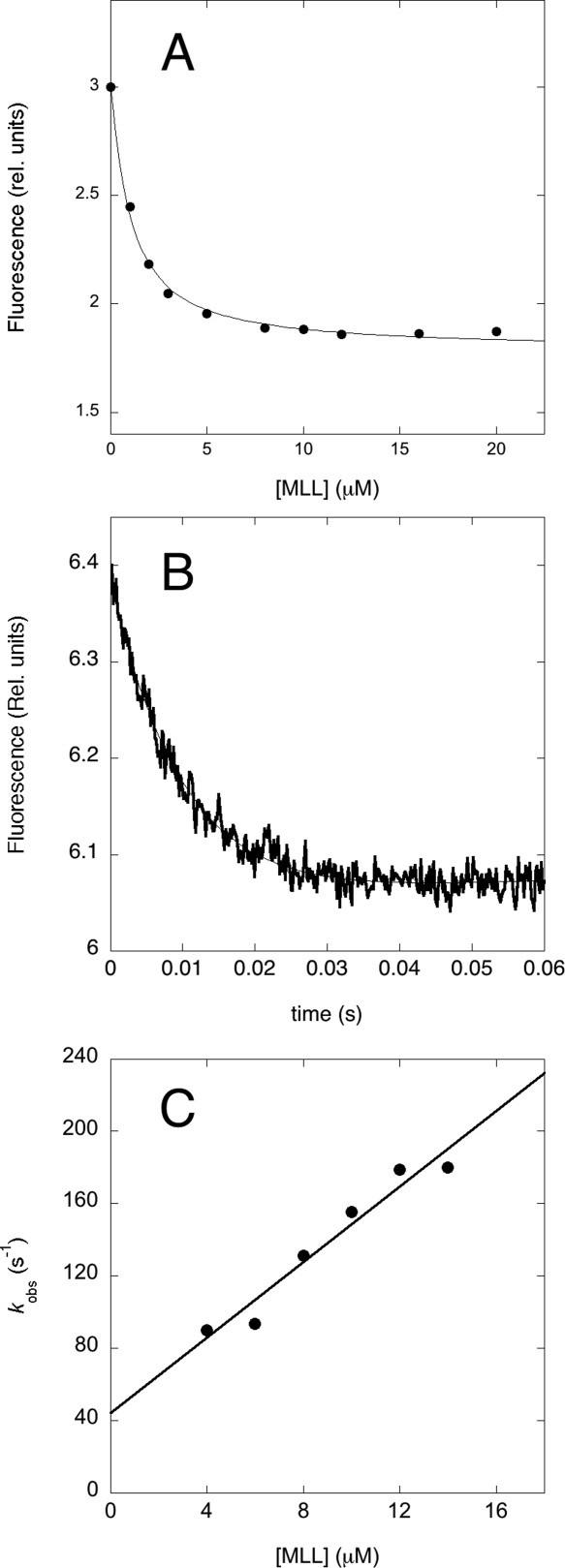

Figure 2.

The binding of KIX Y631W to MLL. (A). Equilibrium binding titration of KIX with MLL monitored by the change in intrinsic fluorescence at 370 nm. The experiments were done at pH 7.2 in the presence of 150 mM KCl and 10°C, at a constant concentration of KIX of 0.4 µM. (B) A typical fluorescence time-course of binding between KIX Y631W and MLL. Data were recorded at pH 7.2 in the presence of 150 mM KCl and 10°C, concentrations were 0.4 µM for KIX Y631W and 6 µM for MLL. (C) Pseudo-first order plot of the observed rate constant in the binding of KIX Y631W to MLL. Quantitative analysis using a linear regression yields an association bimolecular rate constant kon of (11 ± 1) × 106 M−1 s−1 and a dissociation rate constant koff of 42 ± 10 s−1.

In order to address the binding mechanism of KIX to MLL we performed kinetic experiments at 10°C (because, as detailed below, the reaction would be to fast at >20°C). In particular, by taking advantage of the fluorescence signal change upon binding of KIX Y631W to MLL, we carried out kinetic binding experiments by mixing a constant concentration of KIX Y631W (2 µM) with excess concentrations of MLL, typically from 4 to 14 µM. Figure 2(B) depicts a typical fluorescence trace observed in these binding experiments. Under all the explored conditions, the observed time course was satisfactorily fitted by a single-exponential function, suggesting that, despite its inherent complexity and in analogy to the binding between KIX and c-Myb, the folding upon binding reaction of MLL to KIX follows a simple two-state mechanism, without evidence for accumulation of detectable intermediates. The two-state nature of the reaction was also confirmed by the linear dependence of the observed rate constant [Fig. 2(C)] on MLL concentration (under quasi-pseudo first order conditions). Analysis of the data yields an association bimolecular rate constant kon of (11 ± 1) × 106 M−1 s−1 and a dissociation rate constant koff of 42 ± 10 s−1. The latter was determined also by displacement experiment (described below), which yielded a value of koff of 33 ± 2 s−1. The overall KD obtained from kinetic experiments carried out at pH 7.2 in the presence of 150 mM KCl and 10°C is 3.8 ± 1.0 µM, to be compared with the values obtained from equilibrium experiments under similar experimental conditions (1–2 µM).

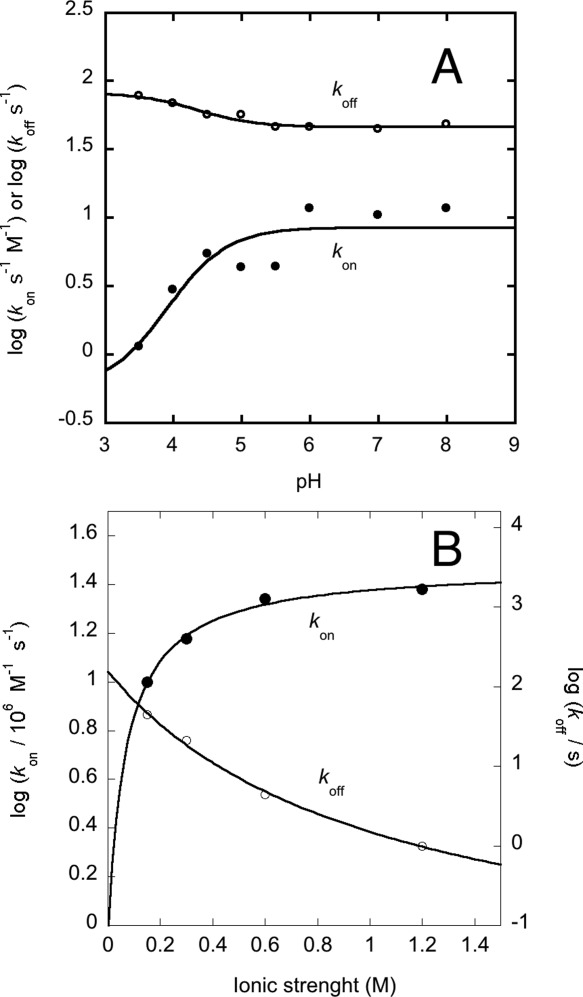

To address the mechanism of binding between KIX/Y631W and MLL, we resorted to explore the reaction at different pHs and ionic strengths. The dependence of the microscopic kinetic constants kon and koff from pH 3.5 to 8.0 is reported in Figure 3(A). It is evident that the logarithm of both rate constants displays a sigmoidal profile as a function of pH; the dependence of both kon and koff are satisfactorily fitted by an equation implying the protonation of a single group, with pKa of about 4. Additional insight into the mechanism of recognition between KIX/Y631W and MLL was provided by experiments at increasing concentrations of KCl, varying the ionic strength from 150 mM to 1.2 M [Fig. 3(B)]. Lower ionic strengths could not be explored due to the poor solubility of KIX in the absence of salt. Inspection of Figure 3(B) clearly reveals that the affinity of the complex increases remarkably with increasing ionic strength, as mirrored by both an increase in the association rate constant and a decrease of the dissociation rate constant. A plausible interpretation of the dependence of binding kinetics on pH and ionic strength, vis-a-vis the three dimensional structure of the complex between KIX and MLL, is presented in the discussion section.

Figure 3.

The binding of KIX Y631W to MLL under different experimental conditions. (A) Dependence of the logarithm of the association and dissociation rate constants on pH. The lines are the best fit to the protonation of a single group, with an apparent pKa of about 4 for both rate constants. (B) Dependence of the logarithm of the association and dissociation rate constants on ionic strength. It may be noticed that the increase in binding affinity with increasing ionic strength is accounted for both an increase of the association rate constant and a decrease of the dissociation rate constant. The lines are the best fit to the Debye–Hückel equation.

As recalled in the Introduction, an interesting feature of the KIX domain is that, despite its small size, it is capable to bind different IDPs via two distinct binding pockets; namely, the so-called ‘MLL’ and the ‘c-Myb’ sites. Previous work5,7,14–16 suggested that the two binding pockets, whilst located in topologically distinct regions of the protein, communicate allosterically, since the binding of MLL affects the binding of c-Myb on the opposite side of the KIX domain. To address the mechanism of allosteric communication, we compared the kinetics of binding of KIX to c-Myb in the presence of MLL. In analogy to our previous work,9,11 the binding of KIX and c-Myb was studied by employing a pseudo-wild-type domain where a tryptophan residue was engineered near the binding pocket of c-Myb; namely, the KIX/Y658W mutant (i.e., position 72 when considering the numbering referring to the isolated KIX domain). Figure 4(A) depicts a comparison of the observed pseudo-first-order kinetics for the binding of c-Myb to the KIX–MLL complex, in the presence of different constant concentrations of MLL. The experimental conditions were chosen to compare with the previously published equilibrium data measured by ITC,7 but were recorded at 10°C instead of 25°C because the reaction would be too fast for our stopped-flow apparatus. It is evident that, whilst preincubation of KIX with MLL appears to decrease the speed of the reaction (by decreasing the dissociation rate constant), the slope of the observed dependence, reflecting the association rate constants, is insensitive to the presence of MLL.

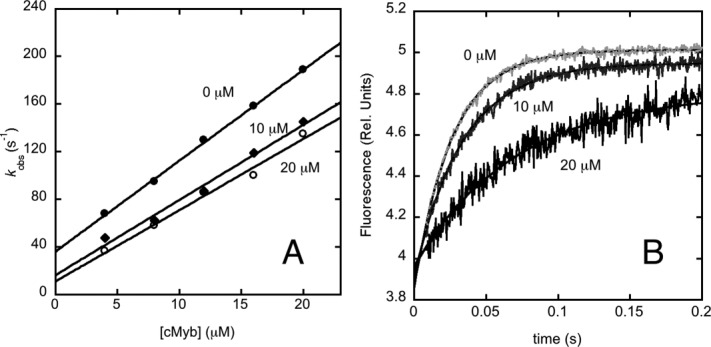

Figure 4.

Allosteric communication between c-Myb and MLL binding sites. (A) Pseudo-first order plot for the observed binding rate constant between KIX Y658W and c-Myb in the presence of different concentrations of MLL, that is, zero MLL (filled circles); 10 µM MLL (diamonds); and 20 µM MLL (open circles). (B) Displacement of the ternary complex [MLL: KIX Y658W:c-Myb] by an excess of wild-type KIX at 60 µM after mixing. The concentrations employed were: 10 µM for both KIX and c-Myb, and MLL concentrations of 0, 10, and 20 µM.

Data in Figure 4(A) allow, in theory, to calculate the dissociation rate constant by extrapolation. Very often, however, the experimental errors arising from these extrapolations are fairly high, with a major source of error arises from the linearity of the plot. In fact, whilst the rate constants obtained from exponential fit of the time courses typically display an experimental error that is relative to their magnitude, the linear extrapolation method gives rise to an error that is only correlated to the scatter of the plot. Hence, additional care is recommended when the extrapolated koff display a low value in comparison with the measured rate constants. In the case of the data reported in Figure 4(A), we therefore resorted to obtain a more accurate determination of the dissociation rate constant by a different approach. In analogy to classical experiments on myoglobin17 the time course of the dissociation was measured by displacement of a preincubated complex between two partners mixed with an excess of a competing reactant. This method may also allow to test for the presence of additional, spectroscopically silent, reactions occurring after the formation of the bimolecular complex. Thus, we performed a displacement experiment by challenging the ternary complex MLL: KIX/Y658W:c-Myb with an excess of wild-type KIX. The concentrations employed were 10 µM for both KIX and c-Myb, and 0, 10, and 20 µM for MLL. Dissociation was triggered by rapid mixing with wild-type KIX at concentrations from 20 to 60 µM. As expected from theory, the observed kinetics were insensitive to the concentration of wild-type KIX. It was found that the dissociation rate constant, which is koff = 36 ± 0.8 s−1 in the absence of MLL, drops to koff = 24 ± 0.7 s−1 in the presence of 10 µM MLL and to koff = 18 ± 1.1 s−1 in the presence of 20 µM MLL [Fig. 4(B)], thus confirming the overall behavior depicted in Figure 4(A). This observation supports the view that there is an allosteric communication between the MLL and c-Myb binding sites, and suggests that MLL increases the affinity of KIX for c-Myb lowering its dissociation rate constant by a factor of 2.

Discussion

The mechanism of binding between IDPs and their partners is, in theory, a complex reaction involving at least two steps: the recognition of the two molecules and the binding induced folding of the IDP.18–20 Surprisingly, however, the recent kinetic analysis on different IDPs appears to suggest that folding and binding occur in a cooperative manner, with no direct evidence for intermediates and often involving a simple two-state reaction.9,21–24 Because of its ability to bind different IDPs via two alternative binding sites, the KIX domain is a very interesting candidate to address the mechanisms by which IDP's recognize their partner as well as to investigate the energetic communication between the different topologically distinct sites.7 Here we complement our earlier work on the interaction between KIX and c-Myb by addressing the binding between KIX and MLL, as well as the allosteric effects between the sites. In analogy to what previously observed in the case of c-Myb,9 also MLL binds KIX via a simple two-state process. Thus, despite the inherent complexity of the process, it appears that, under all conditions explored, folding and binding are coupled and co-operative. Indeed no transient intermediates could be detected by fluorescence spectroscopy, the kinetic time courses being described by a single exponential; and likewise the dissociation equilibrium constant is not inconsistent with that calculated from kinetic experiments as well as from equilibrium ITC and fluorescence spectroscopy.

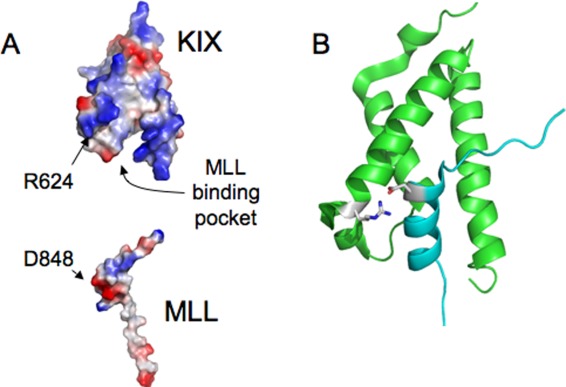

In an effort to characterize the binding mechanism of MLL to KIX we measured the reaction kinetics at different pH values. Interestingly both the association and the dissociation rate constants displayed sigmoidal pH dependence, consistent with the titration a single group with pKa ∼4 for both rate constants. Examination of the structure of the complex between folded MLL and KIX reveals the presence at the interface of a single salt bridge between R624 in KIX and D848 in MLL (Fig. 5). D848 is compatible with a pKa of 4 and it is thus likely to be responsible for the pH dependence of both rate constants. Thus, the data suggest a scenario whereby the rate limiting transition state is characterized by a partial formation of the salt bridge between R624 in KIX and D848 in MLL, which is then locked in place only in the fully folded state.

Figure 5.

Structural analysis of the MLL binding pocket. (A) The electrostatic potentials of KIX (top) and MLL (bottom) are highlighted. It is evident that, over-and-above the interaction between R624 in KIX and D848 in MLL, the binding pocket of KIX displays a positively charged surface which does not match with a negative region in MLL. (B) Cartoon representation of the structure of the binary complex between KIX and MLL. The residues R624 in KIX and D848 in MLL are highlighted in sticks. The orientation of the two domains is the same in both panels.

It is of interest to comment on the magnitude of the observed bi-molecular association rate constant between KIX and MLL. In fact, whilst setting an upper bound for diffusion limited reaction is extremely difficult and demands approximations, it has been recently claimed using IDPs as model systems, that the speed for diffusion limited association reactions would be in the order of 105−106 M−1 s−1, with faster rate constants being associated to electrostatically assisted interactions.23 In this context, it is interesting to observe that, in the case of the association between KIX and MLL, whilst the observed bi-molecular rate constant at low ionic strength is about 107 M−1 s−1, the value increases as the ionic strength is increased. Thus, not only the bimolecular rate constant is higher than what suggested by others as a speed limit, but the interaction is somewhat electrostatically unfavorable, being accelerated, rather than decelerated, by screening the charges with increasing ionic strength. An analysis of the electrostatic surface of KIX and MLL, reported in Figure 5, appears consistent with these observations. In fact, whilst charge complementarity at the level of the salt bridge between R624 in KIX and D848 in MLL is evident, in KIX a large surface displaying a positive charge is located in the opposite side of the binding pocket, with no correspondence to a negative region in MLL. This lack of optimization of the binding pocket may be a reflection of the promiscuity of KIX that binds, for example, the FOXO3a protein25 and the transactivation domain of p53,26 always in the same pocket.

The function of the KIX domain as a mediator of protein-protein interactions between different transcription factors is highlighted by its capability to bind different partners.6 It has been observed that there is an allosteric communication between the two distinct binding pockets, such that the binding of MLL promotes the binding of c-Myb by a factor of 2.7 NMR relaxation dispersion experiments,14,15 as well as molecular dynamics simulations,16 suggested that such an allosteric coupling is obtained by inducing a redistribution of the relative population of KIX from a lower to a higher affinity state where the second binding site is already preformed.15 This scenario is consistent with a Monod–Wyman–Changeaux allosteric model27 and involves a structural re-arrangement of the hydrophobic core of the protein.14–16 The kinetic experiments presented above unambiguously show that MLL promotes binding of c-Myb by decreasing the dissociation rate constant from KIX, the association rate constant being insensitive to the presence of MLL. Thus, we conclude that formation in KIX of the correct binding site for c-Myb has little effect in initial recognition with negligible effect in the transition state free energy, whereas it enhances interactions that are formed downhill the rate limiting barrier. Future work based on site-directed mutagenesis will unveil the atomistic and energetic details of the allosteric coupling between the MLL and the c-Myb binding sites on KIX.

Materials and Methods

Site-directed mutagenesis and protein expression and purification

wtKIX from Mus musculus CBP (residues 586–672) cloned into pRSET vector (Invitrogen) and resulting in a clone expressing His-tagged Kix, was generously provided by Prof. Per Jemth (Uppsala University, Sweden). The site-directed mutants Y631W and Y658W were obtained by using the QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing. Proteins were purified by using a nickel(II)-charged chelating sepharose FF (Amersham Biosciences) column equilibrated with 40 mM Tris–HCl and 400 mM NaCl, pH 8.5. The His-tagged KIX variants were eluted with 250 mM imidazole. The samples were then diluted fourfold in 40 mM Tris, pH 8.5 and all minor impurities were removed by the purification step on a Q-Sepharose column equilibrated with 40 mM Tris, pH 8.5. The proteins passed through the Q-column; the flow-through containing the protein was collected and concentrated. The purity of the protein was confirmed by SDS-PAGE.

The engineered construct of c-Myb was fused to the prodomain of subtilisin was cloned into pPAL7 vector (BioRad). The protein was purified by using a cation-exchange chromatography (S-Sepharose column equilibrated with 40 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.5). c-Myb was eluted with 850 mM NaCl. The sample was then diluted fourfold in 40 mM Tris, pH 8.5 and all minor impurities were removed by the purification step on a nickel(II)-charged chelating Sepharose FF (Amersham Biosciences) column equilibrated with 40 mM Tris–HCl equilibrated pH 8.5. The protein passed through the nickel(II) column; the flow-through containing the protein was collected, and concentrated. The purity of the protein was confirmed by SDS-PAGE.

The mixed lineage leukemia protein (MLL) activation domain (sequence YNILPSDIMDFVLKNTPSMQALGE) was purchased from JPT Peptide Technologies (Berlin, Germany).

Equilibrium experiments

Fluorescence

Equilibrium binding experiments were carried on a Fluoromax single photon counting spectrofluorometer (Jobin-Yvon). Tryptophan fluorescence emission spectra were recorded in a cuvette (1 cm light path) between 300 and 400 nm. The excitation wavelength was 280 nm. KIX Y631W concentration was typically 2 µM.

Stopped-flow measurements

Single mixing kinetic binding and displacement experiments were carried out on an SX-18 stopped-flow instruments (Applied Photophysics, Leatherhead, UK); the excitation wavelength was 280 nm, and the fluorescence emission was measured using a 320 nm cutoff glass filter.

KIX:MLL binding kinetics

Pseudo-first order binding experiments were performed by using a constant concentration of KIX Y631W of 2 µM with increasing concentrations of MLL, typically ranging from 4 to 14 μM. The experiments were performed at 10°C and the buffers used for the pH dependence were 50 mM Formate, 150 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, pH 3.5; 50 mM acetate, 150 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, pH 4.0, 4.5, 5.0, 5.5; 50 mM Bis–Tris, 150 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, pH 6.0; 50 mM sodium phosphate, 150 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, pH 7.0; 50 mM Tris–HCl, 150 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, pH 8.0. Buffers used for the KCl dependence were: 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0, 1 mM DTT, and 150 mM, 300 mM, 600 mM, and 1.2 M KCl. All reagents were of analytical grade.

Allostery binding kinetics

Pseudo-first-order binding experiments were performed by a rapid mixing of KIX Y658W at constant concentration of 2 μM versus increasing concentration of c-Myb, typically ranging from 4–20 μM, and then using a preincubated complex of KIX Y658W at the concentration of 2 μM with MLL at the concentration of 10 and 20 μM, versus increasing concentration of c-Myb. The buffer used was 50 mM Tris, 150 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, pH 7.0, and the experiments were performed at 10°C.

Displacement kinetics

The dissociation rate constants were calculated by displacement kinetic experiments. KIX Y658W and c-Myb were first preincubated (10 μM KIX and 10 μM c-Myb), then the complex was rapidly mixed with an excess of wild-type KIX (i.e., the wild-type domain with a Tyr at position 73). Then KIX Y658W, c-Myb, and MLL were preincubated (with MLL at the concentration of 10 and 20 μM) and the complex was rapidly mixed with an excess of wild-type KIX. The dissociation process was measured at different relative concentrations of wild-type KIX, ranging from two- to sixfold. The experiments were performed at 10°C and the buffer used was: 50 mM Tris, 150 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, pH 7.0. All reagents were of analytical grade.

Acknowledgments

Work partly supported by grants from the Italian Ministero dell'Istruzione dell'Università e della Ricerca (Progetto di Interesse ‘Invecchiamento’ to S.G.) and Sapienza University of Rome (C26A13T9NB to S.G.).

References

- 1.Ptashne M, Gann A. Transcriptional activation by recruitment. Nature. 1997;386:569–577. doi: 10.1038/386569a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodman RH, Smolick S. CbP/p300 in cell growth, transformation, and development. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1553–1577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kornberg RD. Mediator and the mechanism of transcriptional activation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:235–239. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Radhakrishnan I, Pérez-Alvarado GC, Parker D, Dyson HJ, Montminy MR, Wright PE. Solution structure of the KIX domain of CBP bound to the transactivation domain of CREB: a model for activator: coactivator interactions. Cell. 1997;91:741–752. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80463-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thakur JK, Yadav A, Yadav G. Molecular recognition by the KIX domain and its role in gene regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1147. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Guzman RN, Goto NK, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Structural basis for cooperative transcription factor binding to the CBP coactivator. J Mol Biol. 2006;355:1005–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goto NK, Zor T, Martinez-Yamout M, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Cooperativity in transcription factor binding to the coactivator CREB-binding protein (CBP) J Biol Chem. 2002;277:43168–43174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207660200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zor T, De Guzman RN, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Solution structure of the KIX domain of CBP bound to the transactivation domain of c-Myb. J Mol Biol. 2004;337:521–534. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gianni S, Morrone A, Giri R, Brunori M. A folding-after-binding mechanism describes the recognition between the transactivation domain of c-Myb and the KIX domain of the CREB-binding protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;428:205–209. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.09.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fersht AR, Matouschek A, Serrano L. The folding of an enzyme. I. Theory of protein engineering analysis of stability and pathway of protein folding. J Mol Biol. 1992;224:771–782. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90561-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giri R, Morrone A, Toto A, Brunori M, Gianni S. Structure of the transition state for the binding of c-Myb and KIX highlights an unexpected order for a disordered system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:14942–14947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307337110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Domer PH, Fakharzadeh SS, Chen CS, Jockel J, Johansen L, Silverman GA, Kersey JH, Korsmeyer SJ. Acute mixed-lineage leukemia t(4;11)(q21;q23) generates an MLL-AF4 fusion product. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7884–7888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.16.7884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeleznik-Le NJ, Harden AM, Rowley JD. 11q23 translocations split the “AT-hook” cruciform DNA-binding region and the transcriptional repression domain from the activation domain of the mixed-lineage leukemia (MLL) gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10610–10614. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brüschweiler S, Schanda P, Kloiber K, Brutscher B, Kontaxis G, Konrat R, Tollinger M. Direct observation of the dynamic process underlying allosteric signal transmission. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:3063–3068. doi: 10.1021/ja809947w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brüschweiler S, Konrat R, Tollinger M. Allosteric communication in the KIX domain proceeds through dynamic repacking of the hydrophobic core. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8:1600–1610. doi: 10.1021/cb4002188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palazzesi F, Barducci A, Tollinger M, Parrinello M. The allosteric communication pathways in KIX domain of CBP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:14237–14242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313548110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Antonini E, Brunori M. Hemoglobin and myoglobin in their reactions with ligands. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: North-Holland Publ Co; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tompa P. The interplay between structure and function in intrinsically unstructured proteins. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:3346–3354. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dunker AK, Silman I, Uversky VN, Sussman JL. Function and structure of inherently disordered proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2008;18:756–764. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uversky VN, Dunker AK. Understanding protein non-folding. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1804:1231–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Narayanan R, Ganesh OK, Edison AS, Hagen SJ. Kinetics of folding and binding of an intrinsically disordered protein: the inhibitor of yeast aspartic proteinase YPrA. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:11477–11485. doi: 10.1021/ja803221c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dogan J, Schmidt T, Mu X, Engström Å, Jemth P. Fast association and slow transitions in the interaction between two intrinsically disordered protein domains. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:34316–34326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.399436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rogers JM, Steward A, Clarke J. Folding and binding of an intrinsically disordered protein: fast, but not ‘diffusion-limited’. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:1415–1422. doi: 10.1021/ja309527h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dogan J, Gianni S, Jemth P. The binding mechanisms of intrinsically disordered proteins. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2014 doi: 10.1039/c3cp54226b. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang F, Marshall CB, Li GY, Yamamoto K, Mak TW, Ikura M. Synergistic interplay between promoter recognition and CBP/p300 coactivator recruitment by FOXO3a. ACS Chem Biol. 2009;4:1017–1027. doi: 10.1021/cb900190u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee CW, Arai M, Martinez-Yamout MA, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Mapping the interactions of the p53 transactivation domain with the KIX domain of CBP. Biochemistry. 2009;48:2115–2124. doi: 10.1021/bi802055v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Monod J, Wyman J, Changeux JP. On the nature of allosteric transitions: a plausible model. J Mol Biol. 1965;12:88–118. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(65)80285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]