Abstract

background

Recent prospective studies have shown a strong inverse association between sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG) concentrations and risk of clinical diabetes in white individuals. However, it remains unclear whether this relationship extends to other racial/ethnic populations.

methods

We evaluated the association between baseline concentrations of SHBG and clinical diabetes risk in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Over a median follow-up of 5.9 years, we identified 642 postmenopausal women who developed clinical diabetes (380 blacks, 157 Hispanics, 105 Asians) and 1286 matched controls (777 blacks, 307 Hispanics, 202 Asians).

results

Higher concentrations of SHBG at baseline were associated with a significantly lower risk of clinical diabetes [relative risk (RR), 0.15; 95% CI, 0.09–0.26 for highest vs lowest quartile of SHBG, adjusted for BMI and known diabetes risk factors]. The associations remained consistent within ethnic groups [RR, 0.19 (95% CI, 0.10–0.38) for blacks; RR, 0.17 (95% CI, 0.05–0.57) for Hispanics; and 0.13 (95% CI, 0.03–0.48) for Asians]. Adjustment for potential confounders, such as total testosterone (RR, 0.11; 95% CI, 0.07–0.19) or HOMA-IR (RR, 0.26; 95% CI, 0.14–0.48) did not alter the RR substantially. In addition, SHBG concentrations were significantly associated with risk of clinical diabetes across categories of hormone therapy use (never users: RRper SD = 0.42, 95% CI, 0.34–0.51; past users: RRper SD = 0.53;, 95% CI, 0.37–0.77; current users: RRper SD = 0.57; 95% CI, 0.46–0.69; P-interaction = 0.10).

conclusions

In this prospective study of postmenopausal women, we observed a robust, inverse relationship between serum concentrations of SHBG and risk of clinical diabetes in American blacks, Hispanics, and Asians/Pacific Islanders. These associations appeared to be independent of sex hormone concentrations, adiposity, or insulin resistance.

Sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG)11 is a homodimeric protein that serves to transport sex steroids in circulation (1–3). Although SHBG’s chief function is classically thought to be regulation of the concentrations of free sex steroids in plasma, recent evidence indicates a more direct role for SHBG through an intracellular signaling cascade mediated by membrane-bound SHBG receptors (4, 5). These novel mechanisms suggest that SHBG may play amore direct role in disease etiology than previously believed.

A large body of clinical studies has consistently shown that SHBG concentrations were lower in patients with type 2 diabetes compared with controls (6–8). In a recent prospective study of white men and women followed for 10 years, participants in the lowest quartile of SHBG concentrations at baseline (5.8 – 24.7 nmol/L) had an approximately 10-fold increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes compared to those in the highest quartile (44.4 – 122.0 nmol/L), even after body mass index (BMI) and other known risk factors were accounted for (9). Instrumental variable analysis with genetic polymorphisms as randomization instruments further corroborated the potentially causal relationship between SHBG concentrations and type 2 diabetes risk, which was confirmed by a subsequent pooled analysis of 15 European populations (10).

To further expand on the prior work conducted in white populations, we investigated the distributions of SHBG and its role in the development of clinical diabetes in black, Hispanic, and Asian participants from the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study (WHI-OS). In particular, we examined the relationship between SHBG and clinical diabetes with a comprehensive assessment of lifestyle factors and biological markers (e.g., adiposity, sex hormones, insulin resistance), including an examination of the influence of postmenopausal hormone therapy on the association between SHBG concentrations and risk of clinical diabetes.

Materials and Methods

study population

WHI-OS was a longitudinal study of postmenopausal women from multiple ethnic groups in the US. Detailed descriptions of the rationale, eligibility, and design have been published elsewhere (11, 12). Briefly, between September 1994 and December 1998, the WHI-OS enrolled a total of 93 676 postmenopausal women aged 50–79 years at 40 clinical centers throughout the US. At baseline, women completed screening and enrollment questionnaires, underwent a physical examination, and provided a fasting blood specimen. Participants were followed annually by self-administered questionnaires that were updated for exposures and medical history. In each questionnaire, women were asked whether their doctor prescribed for the first time any pills or treatments for diabetes (i.e., oral hypoglycemic medications or insulin shots). Eligible cases included women who provided adequate blood specimens and subsequently reported new diabetes treatment with oral hypoglycemic drugs or insulin or hospitalization for diabetes during the follow-up period (median = 5.9 years). Self-reported diabetes validated against medication histories yielded a positive predictive value of 72% and negative predictive values of >99.9% (13). For the current study, we excluded women who reported a history of diabetes or cardiovascular disease at baseline. We further restricted selection of cases and controls to black, Hispanic, and Asian/Pacific Islander women because previous studies of SHBG and diabetes indicated a strong association in white men and women. In accordance with the principles of risk-set sampling, for each new case developed during follow-up, up to 2 controls were selected randomly among women who remained free of clinical diabetes at the time the case was identified. Controls were matched to cases by age (±2.5 years), racial/ethnic group (black, Hispanic, and Asian/Pacific Islander), clinical center (geographic location), time of blood draw (±0.10 h), and length of follow-up. We excluded 1 outlying participant whose SHBG concentrations were over 3.0 SDs above the mean. For the current analysis, 642 incident cases and 1286 controls met the eligibility criteria, of which 380 cases and 777 controls were black, 157 cases and 307 controls were Hispanic, and 105 cases and 202 controls were Asian/Pacific Islander (14, 15). This study was approved by the human study participants review committees at each participating institution, and signed informed consent was obtained from all women enrolled.

assays of biological markers

Fasting serum specimens collected at baseline from each participant were processed locally, frozen, and then shipped to a central repository, where they were stored at −80 °C. All biochemical assays were processed in random order by laboratory staff blinded to case status. Samples from cases and their matched controls were handled identically, shipped in the same batch, and assayed in the same analytical run to reduce systematic bias and interassay variation. Fasting glucose and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) were measured on a chemistry analyzer (Hitachi 911; Roche Diagnostics) using an immunoturbidimetric immunoassay (Denka Seiken), as described previously (14, 15). Fasting insulin concentrations were determined by an ultrasensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay from ALPCO Diagnostics. The homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) and the homeostatic model assessment of β-cell function (HOMA-β) were computed from the mathematical approximation equations originally described by Matthews et al. (16). Serum concentrations of estradiol, testosterone, and SHBG were measured by electrochemilumine scence immunoassays on the Elecsys 2010 immunoanalyzer (Roche Diagnostics). Competitive immunoassays were used to measure estradiol and testosterone, whereas a sandwich format was used to measure SHBG. The lower limits of detection were 5.0 pg/mL (18.4 pmol/L) for estradiol (n = 164 below 5.0 pg/mL), 2.0 ng/dL (0.069 nmol/L) for testosterone (n = 224 below 2.0 ng/dL), and 0.35 nmol/L for SHBG (none below 0.35 nmol/L). We calculated free estradiol and free testosterone using the methods described by Vermuelen et al. (17) and Sodergard et al. (18), which have been previously validated in postmenopausal women (17–21). Standardized, QC serum samples (Liquichek Immunoassay Plus Control, Bio-Rad Laboratories) were run with each batch for QC and evaluation of interbatch variability. CVs on QC samples run on separate days were 5.4% for SHBG, 10.3% for total testosterone, and 12.4% for total estradiol.

statistical analysis

Biomarker values were log transformed to enhance compliance with normality assumptions. Biomarker values that were below the assay’s lower limits of detection were given the midpoint value between zero and the lower limit.

We compared baseline characteristics of participants using mixed-effects regression and conditional logistic regression. Quartiles of circulating SHBG concentrations were defined by the distribution among controls. The association between SHBG and clinical diabetes risk was assessed by conditional logistic regression, in which SHBG concentrations were modeled as continuous (in standardized units) and categorical (quartiles) variables with the lowest quartile as the referent category. To test the linear trend the median value of each category was assigned to individuals and then treated as a continuous variable in the regression models. To aid in the identification of potential confounders, we examined the relations between circulating SHBG concentrations and various demographic and lifestyle factors (see Table 2 in the Data Supplement that accompanies the online version of this article at http://www.clinchem.org/content/vol58/issue10). The primary multivariable model adjusted for potential confounders, which included postmenopausal hormone use, smoking status, alcohol intake, physical activity levels, history of treated hypertension, and history of diabetes in a first-degree relative. To examine the additional role of adiposity after adjustment for potential confounders in the link between SHBG and clinical diabetes risk, we added BMI (continuous) as a covariate in the multivariable model. In a similar manner, we also assessed the influences of biological markers on the SHBG–diabetes relationship by adding waist/hip ratio, hsCRP, HOMA-IR, free estradiol, total estradiol, free testosterone, and total testosterone separately to the multivariable model.

Women with clinical diabetes may represent a specific phenotype of diabetes (e.g., symptomatic cases), which may differ from other diabetes phenotypes (e.g., asymptomatic cases). Thus, as a sensitivity analysis, we assessed the association of SHBG concentrations on a modified definition of type 2 diabetes based on fasting glucose concentrations at baseline, in which we excluded women whose fasting plasma glucose concentrations at baseline were ≥126 mg/dL.

To assess whether obesity or insulin resistance modified the association between SHBG and risk of clinical diabetes, we examined associations of continuous SHBG concentrations, as log-transformed standardized units, on clinical diabetes risk stratified by BMI categories (normal weight, overweight, obese), HOMA-IR (tertiles), postmenopausal hormone therapy use (never users, past users, current users), and self-reported race/ethnicity (black, Hispanic, Asian) using unconditional logistic regression adjusted for matching factors. To minimize residual confounding by incomplete control of BMI or HOMA-IR during the stratification, we further adjusted for the respective variable as a continuous covariate in the models.

Results

Overall, circulating concentrations of SHBG were lower in those who developed clinical diabetes during follow-up [mean = 58.5 nmol/L, median = 41.8, SD = 46.5, interquartile range (IQR) = 28.4 –71.1] compared to controls (mean = 89.9 nmol/L, median = 73.7, SD = 55.6, IQR = 47.5–125.3). Among controls, Asians (mean = 95.4 nmol/L, 95% CI = 87.7–103.0) and Hispanics (mean = 95.8 nmol/L, 95% CI = 89.6–102.0) had higher SHBG concentrations than blacks (mean = 86.2 nmol/L, 95% CI = 82.3–90.1) (Table 1; also see online Supplemental Table 1). However, these racial/ethnic differences in SHBG concentrations were not significant after adjustment for BMI.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants stratified by ethnicity and diabetes case status in the case control study nested within the WHI-OS.

| Blacks | Hispanics | Asians | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (n = 380) |

Controls (n = 777) |

P | Cases (n = 157) |

Controls (n = 307) |

P | Cases (n = 105) |

Controls (n = 202) |

P | |

| Characteristic | |||||||||

| Age, mean (SD), years | 60.9 (6.7) | 61.0 (6.8) | — | 59.9 (6.8) | 60.1 (6.6) | — | 64.0 (7.8) | 63.5 (7.7) | — |

| Family history of diabetes, % | 62.9 | 39.4 | <0.0001 | 65.6 | 40.1 | <0.0001 | 53.3 | 35.6 | 0.0003 |

| Anthropometrics, mean (SD) | |||||||||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 33.7 (7.8) | 29.7 (6.2) | <0.0001 | 31.3 (6.1) | 27.7 (5.2) | <0.0001 | 26.8 (4.2) | 23.9 (4.5) | <0.0001 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 98.0 (15.4) | 87.6 (13.1) | <0.0001 | 93.7 (15.8) | 83.5 (11.2) | <0.0001 | 84.6 (10.1) | 75.7 (9.7) | <0.0001 |

| Waist/hip ratio | 0.86 (0.08) | 0.80 (0.07) | <0.0001 | 0.86 (0.10) | 0.81 (0.07) | <0.0001 | 0.87 (0.07) | 0.80 (0.06) | <0.0001 |

| Lifestyle factors | |||||||||

| Physical activity, median (IQR), MET-h/wk | 4.8 (0.0–12.5) | 6.8 (1.5–15.8) | 0.0004 | 4.7 (0.4–12.4) | 8.3 (1.5–18.3) | 0.07 | 8.6 (2.3–19.2) | 8.6 (3.5–17.8) | 0.98 |

| Current smoker, % | 13.2 | 10.9 | 0.33 | 8.3 | 3.3 | 0.01 | 3.8 | 4.0 | 0.76 |

| Alcohol intake ≥1 drink/week, % | 14.7 | 19.8 | 0.03 | 11.5 | 21.5 | 0.01 | 3.8 | 12.9 | 0.02 |

| Reproductive history | |||||||||

| Current hormone therapy use, % | 23.2 | 34.8 | <0.0001 | 32.5 | 46.6 | 0.003 | 54.3 | 48.0 | 0.30 |

| Age of menarche ≥12 years, % | 72.4 | 78.3 | 0.03 | 76.4 | 73.9 | 0.42 | 77.1 | 77.2 | 0.96 |

| Age at start of menopause, mean (SD), years | 46.4 (7.6) | 46.5 (7.2) | 0.82 | 46.6 (6.7) | 47.7 (6.5) | 0.10 | 48.1 (7.0) | 48.9 (5.7) | 0.26 |

| Years since menopause, mean (SD) | 14.6 (9.9) | 14.4 (9.6) | 0.85 | 13.1 (9.0) | 12.4 (9.1) | 0.17 | 15.3 (9.4) | 15.3 (9.9) | 0.38 |

| Age <25 years at first pregnancy of ≥6 months gestation, % | 54.0 | 52.6 | 0.22 | 48.4 | 45.6 | 0.06 | 38.1 | 32.2 | 0.36 |

| Parity ≥3 live births, % | 47.9 | 44.3 | 0.42 | 69.4 | 57.0 | 0.01 | 44.8 | 49.5 | 0.33 |

| Biomarkers, median (IQR)a | |||||||||

| Free estradiol, pg/mL | 0.32 (0.21–0.49) | 0.26 (0.13–0.44) | 0.01 | 0.29 (0.18–0.45) | 0.24 (0.12–0.41) | 0.15 | 0.27 (0.14–0.47) | 0.17 (0.07–0.3) | 0.02 |

| Total estradiol, pg/mL | 21.4 (14.0–34.9) | 20.9 (11.1–40.3) | 0.26 | 18.4 (11.2–39.9) | 20.4 (9.3–47.7) | 0.64 | 19.5 (9.4–39.5) | 15.6 (6.0–37.0) | 0.78 |

| Free testosterone, ng/dL | 0.15 (0.07–0.29) | 0.08 (0.03–0.16) | <0.0001 | 0.12 (0.04–0.22) | 0.06 (0.02–0.14) | <0.0001 | 0.09 (0.03–0.19) | 0.04 (0.01–0.12) | 0.02 |

| Total testosterone, ng/dL | 14.5 (7.7–24.5) | 11.0 (4.6–21.2) | 0.03 | 11.4 (4.4–21.4) | 9.2 (4.5–17.7) | 0.04 | 9.2 (3.2–15.6) | 7.8 (2.9–16.4) | 0.22 |

| SHBG, nmol/L | 41.5 (28.4–65.9) | 71.5 (45.2–115.6) | <0.0001 | 41.7 (27.9–76.6) | 76.9 (47.6–139.7) | <0.0001 | 48.0 (30.6–73.0) | 79.6 (52.4–133.6) | <0.0001 |

SI conversion factors: estradiol, (pg/mL) × 3.67 = (pmol/L); testosterone, (ng/dL) = 0.0347 = (nmol/L).

Because ethnic differences in the SHBG–diabetes association were not detected (P for heterogeneity = 0.67), we also conducted analyses combining all samples. In all models examined, baseline SHBG concentrations were inversely associated with risk of developing clinical diabetes in a dose–response fashion. During the 6 years of follow-up, women in the highest quartile of circulating SHBG concentrations (range: 125.3–388.8 nmol/L) had an 85% lower risk of clinical diabetes compared to women in the lowest quartile (range: 7.2–47.4 nmol/L) in the unadjusted model (Table 2). Adjustment for potential confounders in the primary multivariable model did not alter estimates substantially [relative risk (RR) = 0.11, 95% CI = 0.07–0.18 for comparison of highest to lowest quartiles]. Examined in separate multivariable models, further adjustments for BMI, waist/hip ratio, hsCRP, estradiol, or testosterone concentrations also did not materially alter estimates. RR estimates were attenuated slightly after adjustment for HOMA-IR, a measure of insulin resistance (RR = 0.26, 95% CI = 0.14–0.48). Despite a high Spearman correlation between HOMA-IR and SHBG concentrations among controls (r = −0.40), the inverse association between SHBG concentrations and risk of clinical diabetes remained robust across multiple models.

Table 2.

RR (95% CI) estimates for clinical diabetes among black, Hispanic, and Asian postmenopausal women by quartiles (Q) of serum SHBG concentrations.

| Model | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | P-trend | RRper-SDa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pooled | ||||||

| Number of participants, (cases/controls) | 366/321 | 123/322 | 92/324 | 61/322 | ||

| Median (range), nmol/L | 33.2 (7.2–47.4) | 57.8 (47.5–73.6) | 91.8 (73.7–125.2) | 164.8 (125.3–388.8) | ||

| Unadjustedb | 1.00 | 0.33 (0.25–0.44) | 0.24 (0.18–0.33) | 0.15 (0.11–0.21) | <0.0001 | 0.48 (0.43–0.54) |

| Multivariableb | 1.00 | 0.36 (0.25–0.51) | 0.25 (0.17–0.37) | 0.11 (0.07–0.18) | <0.0001 | 0.44 (0.37–0.52) |

| Multivariable + BMI | 1.00 | 0.36 (0.25–0.53) | 0.29 (0.19–0.44) | 0.15 (0.09–0.26) | <0.0001 | 0.49 (0.41–0.58) |

| Multivariable + waist/hip ratio | 1.00 | 0.38 (0.26–0.55) | 0.29 (0.19–0.45) | 0.13 (0.08–0.23) | <0.0001 | 0.47 (0.40–0.57) |

| Multivariable + hsCRP | 1.00 | 0.44 (0.29–0.65) | 0.28 (0.18–0.44) | 0.13 (0.07–0.23) | <0.0001 | 0.48 (0.40–0.58) |

| Multivariable + HOMA-IR | 1.00 | 0.58 (0.37–0.89) | 0.47 (0.29–0.76) | 0.26 (0.14–0.48) | <0.0001 | 0.63 (0.52–0.77) |

| Multivariable + free estradiol | 1.00 | 0.40 (0.27–0.57) | 0.29 (0.19–0.43) | 0.12 (0.07–0.20) | <0.0001 | 0.47 (0.40–0.56) |

| Multivariable + total estradiol | 1.00 | 0.36 (0.25–0.52) | 0.24 (0.16–0.35) | 0.09 (0.05–0.15) | <0.0001 | 0.42 (0.36–0.50) |

| Multivariable + free testosterone | 1.00 | 0.38 (0.26–0.55) | 0.29 (0.19–0.43) | 0.14 (0.08–0.24) | <0.0001 | 0.47 (0.39–0.56) |

| Multivariable + total testosterone | 1.00 | 0.36 (0.25–0.51) | 0.25 (0.17–0.37) | 0.11 (0.07–0.19) | <0.0001 | 0.45 (0.38–0.53) |

| Blacks | ||||||

| Number of participants, cases/controls | 212/194 | 80/195 | 51/193 | 37/195 | ||

| Median, (range), nmol/L | 31.8 (10.1–45.1) | 55.7 (45.2–71.5) | 87.5 (71.6–115.0) | 157.6 (115.6–388.8) | ||

| Unadjusted | 1.00 | 0.41 (0.29–0.57) | 0.25 (0.17–0.37) | 0.18 (0.12–0.27) | <0.0001 | 0.49 (0.42–0.56) |

| Multivariableb | 1.00 | 0.47 (0.30–0.72) | 0.26 (0.15–0.44) | 0.14 (0.07–0.26) | <0.0001 | 0.46 (0.37–0.57) |

| Multivariable + BMI | 1.00 | 0.42 (0.26–0.66) | 0.30 (0.17–0.51) | 0.19 (0.10–0.38) | <0.0001 | 0.50 (0.40–0.63) |

| Multivariable + waist/hip ratio | 1.00 | 0.46 (0.29–0.72) | 0.28 (0.16–0.49) | 0.18 (0.09–0.35) | <0.0001 | 0.50 (0.40–0.63) |

| Multivariable + hsCRP | 1.00 | 0.49 (0.30–0.79) | 0.31 (0.17–0.56) | 0.17 (0.08–0.36) | <0.0001 | 0.52 (0.41–0.66) |

| Multivariable + HOMA-IR | 1.00 | 0.60 (0.35–1.03) | 0.46 (0.24–0.88) | 0.35 (0.16–0.77) | 0.002 | 0.70 (0.54–0.91) |

| Multivariable + free estradiol | 1.00 | 0.51 (0.32–0.79) | 0.32 (0.18–0.54) | 0.16 (0.08–0.31) | <0.0001 | 0.50 (0.40–0.62) |

| Multivariable + total estradiol | 1.00 | 0.46 (0.30–0.72) | 0.26 (0.16–0.45) | 0.12 (0.06–0.23) | <0.0001 | 0.45 (0.36–0.56) |

| Multivariable + free testosterone | 1.00 | 0.52 (0.33–0.82) | 0.34 (0.20–0.59) | 0.24 (0.12–0.47) | <0.0001 | 0.55 (0.43–0.69) |

| Multivariable + total testosterone | 1.00 | 0.46 (0.29–0.72) | 0.26 (0.16–0.45) | 0.15 (0.08–0.30) | <0.0001 | 0.47 (0.38–0.59) |

| Hispanics | ||||||

| Number of participants (cases/controls) | 86/77 | 32/77 | 27/77 | 12/76 | ||

| Median (range), nmol/L | 32.3 (8.5–47.6) | 59.8 (47.6–76.9) | 106.5 (77.1–139.7) | 176.2 (140.7–356.4) | ||

| Unadjusted | 1.00 | 0.34 (0.19–0.61) | 0.32 (0.18–0.57) | 0.11 (0.05–0.25) | <0.0001 | 0.51 (0.40–0.63) |

| Multivariableb | 1.00 | 0.51 (0.23–1.16) | 0.41 (0.18–0.93) | 0.11 (0.03–0.36) | 0.0003 | 0.50 (0.36–0.72) |

| Multivariable + BMI | 1.00 | 0.59 (0.25–1.38) | 0.53 (0.22–1.26) | 0.17 (0.05–0.57) | 0.01 | 0.56 (0.39–0.82) |

| Multivariable + waist/hip ratio | 1.00 | 0.49 (0.21–1.16) | 0.41 (0.17–0.99) | 0.13 (0.04–0.43) | 0.001 | 0.51 (0.35–0.74) |

| Multivariable + hsCRP | 1.00 | 0.60 (0.24–1.50) | 0.37 (0.14–0.99) | 0.10 (0.03–0.36) | 0.001 | 0.48 (0.32–0.72) |

| Multivariable + HOMA-IR | 1.00 | 0.68 (0.26–1.81) | 0.85 (0.32–2.26) | 0.25 (0.07–0.95) | 0.13 | 0.67 (0.44–1.02) |

| Multivariable + free estradiol | 1.00 | 0.54 (0.24–1.25) | 0.42 (0.18–1.00) | 0.12 (0.04–0.42) | 0.001 | 0.53 (0.37–0.77) |

| Multivariable + total estradiol | 1.00 | 0.48 (0.21–1.11) | 0.32 (0.13–0.78) | 0.08 (0.02–0.28) | <0.0001 | 0.46 (0.32–0.67) |

| Multivariable + free testosterone | 1.00 | 0.55 (0.24–1.25) | 0.44 (0.19–1.05) | 0.13 (0.04–0.44) | 0.002 | 0.52 (0.36–0.76) |

| Multivariable + total testosterone | 1.00 | 0.52 (0.23–1.17) | 0.40 (0.18–0.92) | 0.11 (0.03–0.36) | 0.0003 | 0.51 (0.36–0.72) |

| Asian/Pacific Islanders | ||||||

| Number of participants, cases/controls | 60/51 | 19/50 | 16/50 | 10/51 | ||

| Median (range), nmol/L | 34.7 (7.2–52.4) | 63.9 (52.6–79.4) | 102.6 (79.8–132.4) | 165.8 (133.6–229.1) | ||

| Unadjusted | 1.00 | 0.39 (0.20–0.75) | 0.23 (0.11–0.49) | 0.15 (0.07–0.36) | <0.0001 | 0.42 (0.31–0.56) |

| Multivariablec | 1.00 | 0.28 (0.10–0.75) | 0.11 (0.03–0.39) | 0.08 (0.02–0.27) | <0.0001 | 0.28 (0.17–0.46) |

| Multivariable + BMI | 1.00 | 0.31 (0.11–0.87) | 0.14 (0.04–0.52) | 0.13 (0.03–0.48) | 0.001 | 0.31 (0.18–0.53) |

| Multivariable + waist/hip ratio | 1.00 | 0.36 (0.13–1.03) | 0.11 (0.03–0.46) | 0.09 (0.02–0.38) | 0.0003 | 0.29 (0.16–0.52) |

| Multivariable + hsCRP | 1.00 | 0.23 (0.07–0.78) | 0.14 (0.03–0.55) | 0.08 (0.02–0.38) | 0.001 | 0.29 (0.15–0.53) |

| Multivariable + HOMA-IR | 1.00 | 0.43 (0.11–1.68) | 0.14 (0.03–0.74) | 0.09 (0.02–0.57) | 0.01 | 0.34 (0.18–0.66) |

| Multivariable + free estradiol | 1.00 | 0.30 (0.11–0.81) | 0.11 (0.03–0.37) | 0.07 (0.02–0.27) | <0.0001 | 0.26 (0.16–0.45) |

| Multivariable + total estradiol | 1.00 | 0.27 (0.10–0.72) | 0.09 (0.03–0.32) | 0.05 (0.01–0.22) | <0.0001 | 0.21 (0.12–0.39) |

| Multivariable + free testosterone | 1.00 | 0.23 (0.08–0.65) | 0.08 (0.02–0.30) | 0.05 (0.01–0.20) | <0.0001 | 0.22 (0.12–0.40) |

| Multivariable + total testosterone | 1.00 | 0.25 (0.09–0.71) | 0.09 (0.03–0.34) | 0.06 (0.02–0.23) | <0.0001 | 0.26 (0.15–0.45) |

RRs represent a 1-unit increment in the log-transformed SD of SHBG concentrations among control participants (log-SD by ethnic group: blacks = 0.62, Hispanics = 0.68, Asians = 0.60 log-nmol/L).

Unadjusted conditional logistic regression models accounted for matching factors (age, race/ethnicity, clinical center, time of blood draw, and duration of follow-up).

Multivariable conditional logistic model further adjusted for postmenopausal hormone use, physical activity levels, cigarette smoking status, alcohol intake, history of hypertension, and family history of diabetes.

To further assess these associations using an alternate subphenotype of type 2 diabetes that omitted potentially asymptomatic cases, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by excluding 218 individuals whose baseline fasting plasma glucose concentrations were ≥126 mg/dL (6.99 mmol/L). After these exclusions, the inverse associations between SHBG concentrations and clinical diabetes risk remained strong (RR = 0.26, 95% CI = 0.18–0.37, comparing highest to lowest quartiles) (see online Supplemental Table 3).

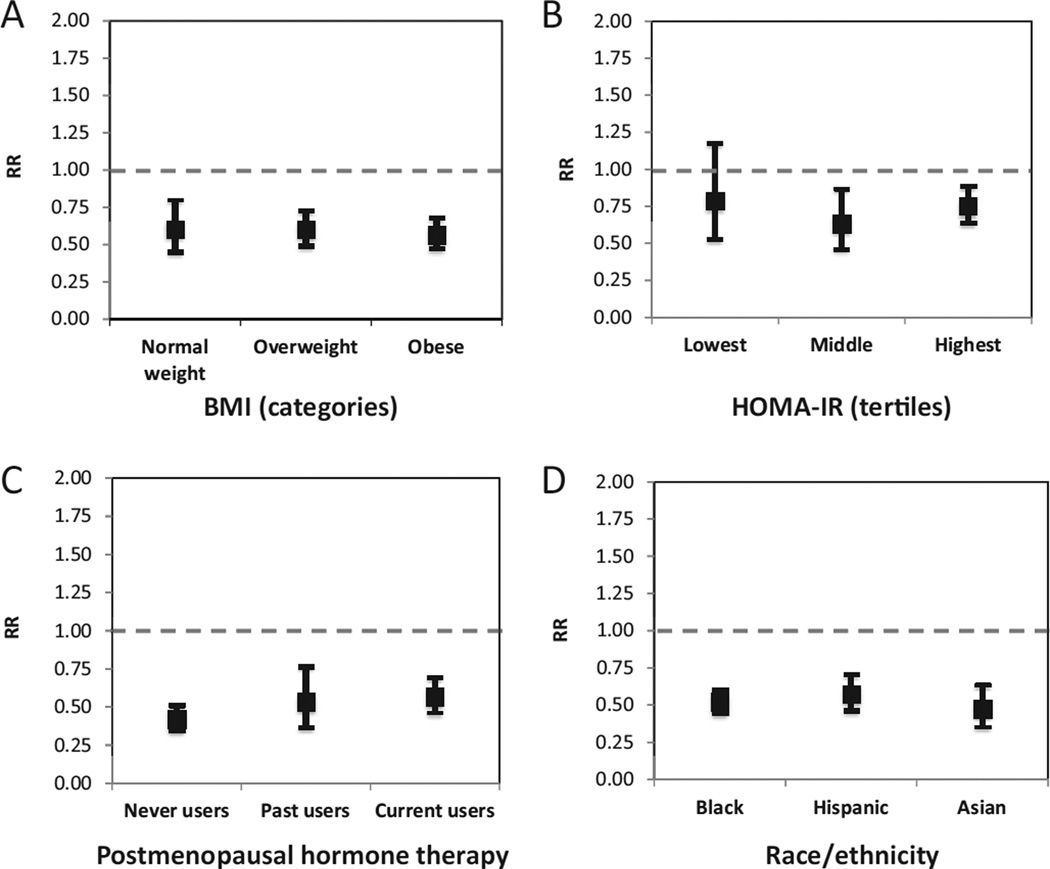

In subgroup analyses, the SHBG–diabetes association was not modified by BMI categories, HOMA-IR categories, use of postmenopausal hormone therapy, or race/ethnicity (Fig. 1; also see online Supplemental Table 4). Interestingly, SHBG concentrations appeared to be a stronger predictor of clinical diabetes risk among women with fasting glucose <100 mg/dL (5.55 mmol/L) at baseline (RRper SD = 0.57, 95% CI = 0.47–0.70) compared to women with fasting glucose ≥100 mg/dL (RRper SD = 0.76, 95% CI = 0.61–0.94, P-interaction = 0.005) (see online Supplemental Table 5).

Fig. 1. RRs (95% CI) for clinical diabetes per unit increase in SHBG concentration by (A) BMI category, (B) HOMA-IR tertiles, (C) use of postmenopausal hormone therapy, and (D) racial/ethnic group.

Unit increases represent the log-transformed SD (log-SD) of the SHBG distribution among controls (log-SD = 0.63 log-nmol/L).

Discussion

In this large cohort of black, Hispanic, and Asian postmenopausal women in the US, low circulating concentrations of SHBG at baseline were significantly and prospectively associated with increased risk of clinical diabetes. This robust association was identical in obese and nonobese individuals as well as across racial/ethnic groups and by postmenopausal hormone therapy categories. In addition, these associations were independent of known clinical diabetes risk factors, including age, race/ethnicity, BMI, reproductive factors, inflammatory markers, insulin resistance, and sex hormone concentrations.

Few studies have directly examined the relationship between serum SHBG concentrations and risk of type 2 diabetes in non white populations. In a cross-sectional study of 483 Japanese-Americans, SHBG concentrations were higher in controls than in those with type 2 diabetes (22). Similarly, a study of 109 white and Mexican women revealed higher SHBG concentrations among controls compared to diabetes cases. However, the SHBG–diabetes relationship remained uncertain among postmenopausal women in this study (8). A recent multiethnic study of postmenopausal women reported associations of similar magnitude and direction as ours (23). In this study the investigators focused on postmenopausal women who never used post-menopausal hormone therapy, yet we observed that differences in the association between SHBG concentrations and clinical diabetes risk were negligible between never, past, and current users of postmenopausal hormone therapy. This multiethnic study and the present study are 2 of the largest population studies examining the prospective association between SHBG concentrations and risk of type 2 diabetes in black, Hispanic, and Asian Americans. The highly robust associations across these 2 studies were consistent with previous observations in white men and women. Taken together, these findings from multiple large and well-characterized prospective cohorts indicate that the inverse associations between SHBG concentrations and risk of clinical diabetes hold true for all major US ethnic groups.

Classically, the involvement of circulating SHBG in biological functions has been attributed to its regulation of bioavailable sex hormone concentrations. Both testosterone and estradiol may regulate SHBG levels and have been associated with the development of type 2 diabetes (6, 24); therefore, sex hormones may partially explain the association between SHBG and diabetes. However, our analyses indicated that a large portion of SHBG’s influence on clinical diabetes was independent of free or total sex hormone concentrations, suggesting that the observed association between SHBG and diabetes could not be entirely attributed to confounding or mediation by sex hormone concentrations. Nevertheless, because the relationship between estrogen and SHBG are highly dynamic and complex, additional studies are needed to further elucidate the relationship between sex hormones and SHBG on diabetes risk.

Emerging research has revealed a novel mechanism for direct SHBG signaling through membrane-bound SHBG receptors, which operate independently from sex-steroid binding to intracellular receptors (4, 5, 25, 26). In vitro studies have demonstrated that membrane-bound SHBG receptors preferentially bind SHBG proteins that are not bound to steroids (27, 28). Thus, high concentrations of sex hormones may reflect a higher proportion of steroid-bound SHBG, thereby reducing SHBG signaling and subsequently attenuating the association between SHBG and diabetes risk. However, neither endogenous concentrations of estradiol nor testosterone modified the SHBG–diabetes association in our data. Another area needing further research is the identification of the metabolically important tissues in which this novel SHBG-receptor signaling pathway is relevant. SHBG-receptors have been detected primarily in reproductive tissues and their presence in skeletal muscle are likely to be low (29–31). Hepatocytes, the primary source of SHBG synthesis in humans, express SHBG receptors, yet the role of the liver in explaining the SHBG–diabetes association remains unclear (30).

The associations between circulating SHBG concentrations and risk of developing diabetes may be confounded by levels of insulin resistance. Although adjustment for HOMA-IR led to a slight attenuation of the association between SHBG and diabetes risk, the relation remained significant. Even after we minimized the differences in insulin resistance at baseline by excluding all women with impaired fasting glucose (>100 mg/dL or >5.55 mmol/L), the association between SHBG concentrations and diabetes risk remained (data not shown). Thus, our analyses provide evidence for an association between SHBG concentrations and risk of clinical diabetes that was independent of insulin resistance.

Several limitations should be considered in the interpretation of our results. First, only a single measurement of SHBG was used to estimate its relationship with diabetes risk, possibly leading to a conservative estimate. By reducing random within-person variation, multiple measurements of SHBG would have strengthened the observed association further. Also, SHBG is a stable protein with a relatively constant diurnal pattern, and its concentrations tend to be much more reliably measured than those of sex steroids (32, 33). Second, sample sizes were limited within racial/ ethnic groups. Still, this was the largest population in which ethnic-specific associations between circulating SHBG concentrations and risk of diabetes were examined. Nevertheless, the inverse relationship between SHBG concentrations and risk of clinical diabetes was robust and consistently observed within each racial/ethnic group. Another limitation was the use of self-reported clinical diabetes. Although some disease misclassification may have occurred, it was likely to be nondifferential in respect to the exposure; thus, the observed estimates would be biased toward the null, leading to more conservative estimates. Moreover, our sensitivity analysis indicated that the inverse association between SHBG concentrations and clinical diabetes risk remained even when a single measurement of fasting glucose was used to refine our case definition.

In summary, the strong prospective association between circulating concentrations of SHBG and clinical diabetes risk previously reported in white men and women was robustly replicated in black, Hispanic, and Asian/Pacific Islander populations in the US. These data support the notion that SHBG serves as an important biomarker for the prediction of clinical diabetes in US women.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research Funding: NIH (R01 DK066401), NIDDK RO1 62290; the WHI is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, NIH, US Department of Health and Human Services N01WH22110, 24152, 32100-2, 32105-6, 32108-9, 32111-13, 32115, 32118-32119, 32122, 42107-26, 42129-32, and 44221; this study was supported by the NIH (R01 DK066401); B.H. Chen, Burroughs Wellcome Fund Inter-school Training Program in Metabolic Diseases and UCLA Genomic Analysis Training Program (NHGRI T32-HG002536); M.F. Wellons, NHLBI Career Development Award (K23-HL-87114); D.L. White, NIDDK Career Development Award (DK081736-01) and the Houston VA HSR&D Center of Excellence (HFP90-20); S. Liu, Burroughs Wellcome Fund Inter-school Training Program in Metabolic Diseases.

Role of Sponsor: The funding organizations played no role in the design of study, choice of enrolled patients, review and interpretation of data, or preparation or approval of manuscript.

Footnotes

Nonstandard abbreviations: SHBG, sex hormone-binding globulin; BMI, body mass index; WHI-OS, Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance; HOMA-β, homeostatic model assessment of β-cell function; RR, relative risk; IQR, interquartile range.

Author Contributions: All authors confirmed they have contributed to the intellectual content of this paper and have met the following 3 requirements: (a) significant contributions to the conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; (b) drafting or revising the article for intellectual content; and (c) final approval of the published article.

Authors’ Disclosures or Potential Conflicts of Interest: Upon manuscript submission, all authors completed the author disclosure form. Disclosures and/or potential conflicts of interest:

Employment or Leadership: None declared.

Consultant or Advisory Role: None declared.

Stock Ownership: None declared.

Honoraria: None declared.

Expert Testimony: None declared.

Patents: S. Liu, US 20120157378 (application/provisional); J.E. Manson, US 20120157378 (application/provisional).

References

- 1.Rosner W, Deakins SM. Testosterone-binding globulins in human plasma: studies on sex distribution and specificity. J Clin Invest. 1968;47:2109–2116. doi: 10.1172/JCI105896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hammond GL, Bocchinfuso WP. Sex hormone-binding globulin: gene organization and structure/ function analyses. Horm Res. 1996;45:197–201. doi: 10.1159/000184787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hammond GL, Underhill DA, Smith CL, Goping IS, Harley MJ, Musto NA, et al. The cDNA-deduced primary structure of human sex hormone-binding globulin and location of its steroid-binding domain. FEBS Lett. 1987;215:100–104. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80121-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hammes A, Andreassen TK, Spoelgen R, Raila J, Hubner N, Schulz H, et al. Role of endocytosis in cellular uptake of sex steroids. Cell. 2005;122:751–762. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosner W, Hryb DJ, Kahn SM, Nakhla AM, Romas NA. Interactions of sex hormone-binding globulin with target cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;316:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ding EL, Song Y, Malik VS, Liu S. Sex differences of endogenous sex hormones and risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006;295:1288–1299. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.11.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindstedt G, Lundberg PA, Lapidus L, Lundgren H, Bengtsson C, Bjorntorp P. Low sex-hormone-binding globulin concentration as independent risk factor for development of NIDDM. 12-yr follow-up of population study of women in Gothenburg, Sweden. Diabetes. 1991;40:123–128. doi: 10.2337/diab.40.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haffner SM, Valdez RA, Morales PA, Hazuda HP, Stern MP. Decreased sex hormone-binding globulin predicts noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in women but not in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;77:56–60. doi: 10.1210/jcem.77.1.8325960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ding EL, Song Y, Manson JE, Hunter DJ, Lee CC, Rifai N, et al. Sex hormone-binding globulin and risk of type 2 diabetes in women and men. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1152–1163. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perry JR, Weedon MN, Langenberg C, Jackson AU, Lyssenko V, Sparso T, et al. Genetic evidence that raised sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) levels reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:535–544. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson GL, Manson J, Wallace R, Lund B, Hall D, Davis S, et al. Implementation of the women’s health initiative study design. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13:S5–S17. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(03)00043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Design of the Women’s Health Initiative Clinical Trial and Observational Study. The Women’s Health Initiative Study Group. Control Clin Trials. 1998;19:61–109. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(97)00078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Margolis KL, Lihong Q, Brzyski R, Bonds DE, Howard BV, Kempainen S, et al. Validity of diabetes self-reports in the Women’s Health Initiative: comparison with medication inventories and fasting glucose measurements. Clin Trials. 2008;5:240–247. doi: 10.1177/1740774508091749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song Y, Manson JE, Tinker L, Howard BV, Kuller LH, Nathan L, et al. Insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion determined by homeostasis model assessment and risk of diabetes in a multiethnic cohort of women: The Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1747–1752. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu S, Tinker L, Song Y, Rifai N, Bonds DE, Cook NR, et al. A prospective study of inflammatory cytokines and diabetes mellitus in a multiethnic cohort of postmenopausal women. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1676–1685. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.15.1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: Insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28:412–419. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vermeulen A, Verdonck L, Kaufman JM. A critical evaluation of simple methods for the estimation of free testosterone in serum. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:3666–3672. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.10.6079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sodergard R, Backstrom T, Shanbhag V, Carstensen H. Calculation of free and bound fractions of testosterone and estradiol-17 beta to human plasma proteins at body temperature. J Steroid Biochem. 1982;16:801–810. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(82)90038-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Endogenous Hormones and Breast Cancer Collaborative Group. Free estradiol and breast cancer risk in postmenopausal women: Comparison of measured and calculated values. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12:1457–1461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller KK, Rosner W, Lee H, Hier J, Sesmilo G, Schoenfeld D, et al. Measurement of free testosterone in normal women and women with androgen deficiency: comparison of methods. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:525–533. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rinaldi S, Geay A, Dechaud H, Biessy C, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, Akhmedkhanov A, et al. Validity of free testosterone and free estradiol determinations in serum samples from postmenopausal women by theoretical calculations. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:1065–1071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okubo M, Tokui M, Egusa G, Yamakido M. Association of sex hormone-binding globulin and insulin resistance among Japanese-American subjects. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2000;47:71–75. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(99)00106-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalyani RR, Franco M, Dobs AS, Ouyang P, Vaidya D, Bertoni A, et al. The association of endogenous sex hormones, adiposity, and insulin resistance with incident diabetes in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:4127–4135. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edmunds SE, Stubbs AP, Santos AA, Wilkinson ML. Estrogen and androgen regulation of sex hormone binding globulin secretion by a human liver cell line. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1990;37:733–739. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(90)90358-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Malley BW, Schrader WT, Mani S, Smith C, Weigel NL, Conneely OM, Clark JH. An alternative ligand-independent pathway for activation of steroid receptors. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1995;50:333–347. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-571150-0.50020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Porto CS, Lazari MF, Abreu LC, Bardin CW, Gunsalus GL. Receptors for androgen-binding proteins: internalization and intracellular signalling. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1995;53:561–565. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(95)00111-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hryb DJ, Khan MS, Romas NA, Rosner W. Solubilization and partial characterization of the sex hormone-binding globulin receptor from human prostate. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:5378–5383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hryb DJ, Khan MS, Romas NA, Rosner W. The control of the interaction of sex hormone-binding globulin with its receptor by steroid hormones. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:6048–6054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakhla AM, Khan MS, Rosner W. Biologically active steroids activate receptor-bound human sex hormone-binding globulin to cause LNCaP cells to accumulate adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990;71:398–404. doi: 10.1210/jcem-71-2-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frairia R, Fortunati N, Berta L, Fazzari A, Fissore F, Gaidano G. Sex steroid binding protein (SBP) receptors in estrogen sensitive tissues. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1991;40:805–812. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(91)90306-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krupenko SA, Krupenko NI, Danzo BJ. Interaction of sex hormone-binding globulin with plasma membranes from the rat epididymis and other tissues. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1994;51:115–124. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(94)90122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brambilla DJ, Matsumoto AM, Araujo AB, Mc-Kinlay JB. The effect of diurnal variation on clinical measurement of serum testosterone and other sex hormone levels in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:907–913. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lewis JG, Mopert B, Shand BI, Doogue MP, Soule SG, Frampton CM, Elder PA. Plasma variation of corticosteroid-binding globulin and sex hormone-binding globulin. Horm Metab Res. 2006;38:241–245. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-925338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.