Abstract

Low-dose interleukin-2 (IL-2) expands regulatory T cells (Tregs) and natural killer (NK) cells after stem cell transplantation (SCT) and may reduce graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). We hypothesized that ultra-low dose (ULD) IL-2 could serve as an immune-modulating agent for stem cell donors to prevent GVHD following SCT. However, the safety, dose level, and immune signatures of ULD IL-2 in immune-competent healthy subjects remain unknown. Here, we have characterized the phenotype and function of Tregs and NK cells as well as the gene expression and cytokine profiles of 21 healthy volunteers receiving 50,000 to 200,000 units/m2/day IL-2 for 5 days. ULD IL-2 was well tolerated and induced a significant increase in the frequency of Tregs with increased suppressive function. There was a marked expansion of CD56bright NK cells with enhanced interferon-γ (IFN-γ) production. Serum cytokine profiling demonstrated increase of IFN-γ induced protein 10 (IP-10). Gene expression analysis revealed significant changes in a highly restricted set of genes, including FOXP3, IL-2RA, and CISH. This is the first study to evaluate global immune-modulating function of ULD IL-2 in healthy subjects and to support the future studies administrating ULD IL-2 to stem cell donors.

Introduction

Interleukin-2 (IL-2) was originally discovered as a T cell growth factor more than 30 years ago.1,2 It was the first human cytokine used to boost immune responses in hematologic malignancies and solid tumors3,4,5,6 but with limited clinical benefit and significant toxicity when used in high doses.7,8 Subsequent in vivo and in vitro studies have established a role for IL-2 in promoting the development and proliferation of antigen-specific T cells, regulatory T cells (Tregs), and natural killer (NK) cells.9 The dual effects of IL-2 on Tregs and NK cell have sparked interest in the potential of this cytokine to treat autoimmune disease and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) after stem cell transplantation (SCT).9,10 Kennedy-Nasser and Bollard et al.11,12 conducted a clinical protocol of ultra-low dose IL-2 (ULD IL-2: 100,000 to 200,000 IU/m2) early following allogeneic SCT and found a threefold expansion of Tregs with no signs of GVHD. Koreth et al.13 reported major responses in patients with steroid refractory chronic GVHD given low-dose IL-2 (LD IL-2: 300,000 to 3,000,000 IU/m2). Recent data further support the use of LD IL-2 to control GVHD by beneficially favoring proliferation, thymic export, and resistance to apoptosis of Tregs in vivo.14 We hypothesized that ULD IL-2 could serve as an immune-modulating agent for stem cell donors and transplant recipients, expanding both Tregs and NK cells, to prevent GVHD. However, the biological effects of ULD IL-2 in healthy humans are unknown and the optimal dose of the IL-2 for expansion of Tregs and NK cells has not been established. Therefore, we studied the immunobiology of Tregs and NK cells following administration of three different doses of ULD IL-2 to healthy volunteers. In addition, the dynamic molecular and proteomic changes in response to ULD IL-2 were analyzed to identify the underlying pathways involved in IL-2-mediated homeostasis in immune competent individuals.

Results

ULD IL-2 is well tolerated by healthy volunteers

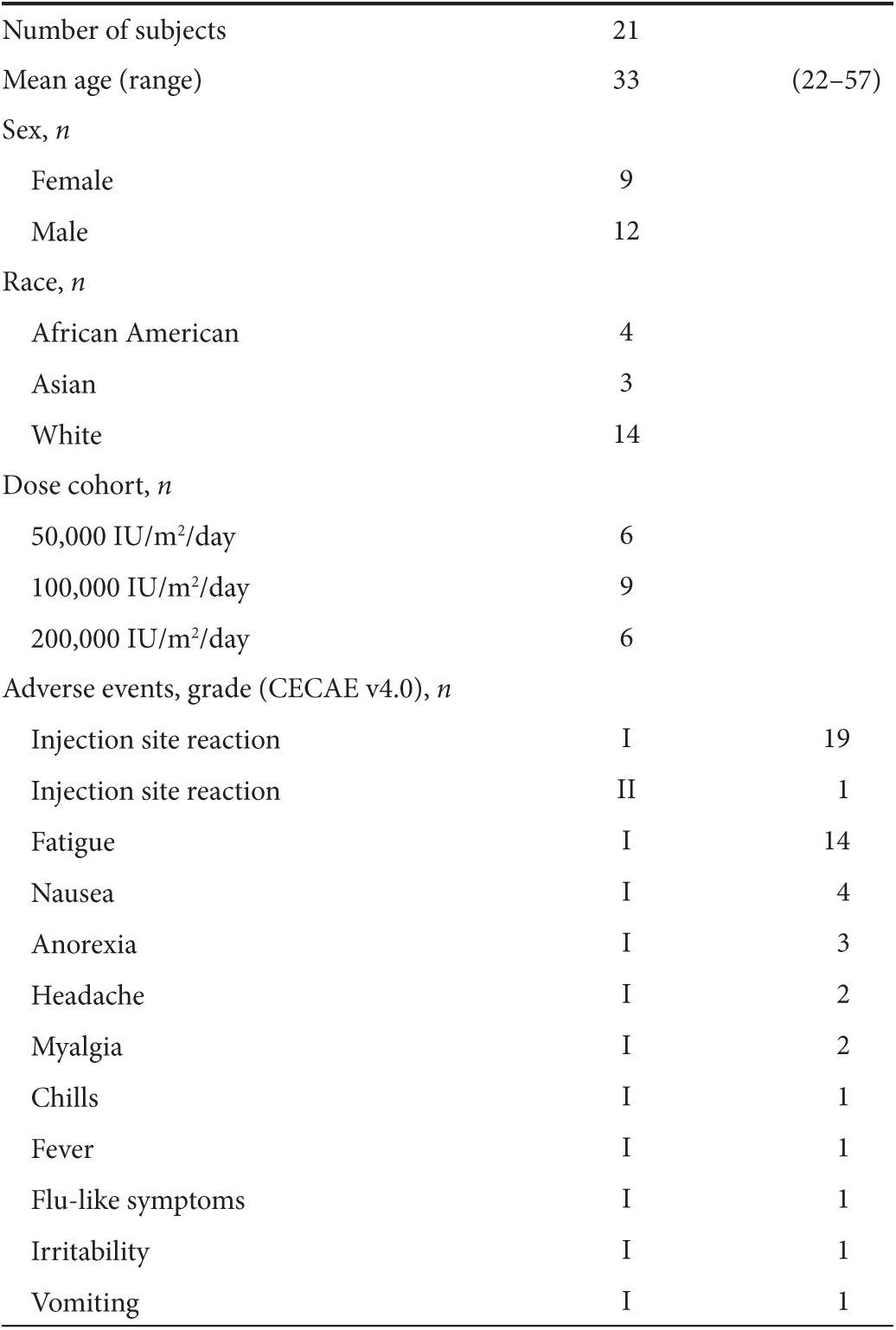

Twenty-one healthy volunteers (mean age 33; range 22–57, female n = 9, male n = 12) were enrolled in the study receiving either: 50,000 IU/m2/day (n = 6), 100,000 IU/m2/day (n = 9), and 200,000 IU/m2/day (n = 6) of ULD IL-2. All subjects tolerated ULD IL-2 with minimal adverse events, including grade 1 injection site reactions (Table 1). No IL-2-related liver or renal toxicities were observed during or after administration. All adverse events completely resolved shortly after the last dose of IL-2. Absolute white blood cell counts were significantly increased at day 4 after initiation of IL-2 (Supplementary Figure S1a; P = 0.001) associated with an increase in absolute numbers of neutrophils, monocytes, and eosinophils (Supplementary Figure S1b, c and data not shown; P = 0.002, P = 0.008, and P = 0.006, respectively), whereas lymphocyte counts remained unchanged (Supplementary Figure S1d; P = 0.249). A subsequent lymphocyte subset analysis demonstrated no significant changes in absolute numbers of CD3+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, CD19+ B cells, and NK cells. Absolute CD8+ T cell counts were slightly decreased at day 4, but this was not statistically significant (P = 0.06) (Supplementary Figure S1e–h).

Table 1. Characteristics of healthy volunteers.

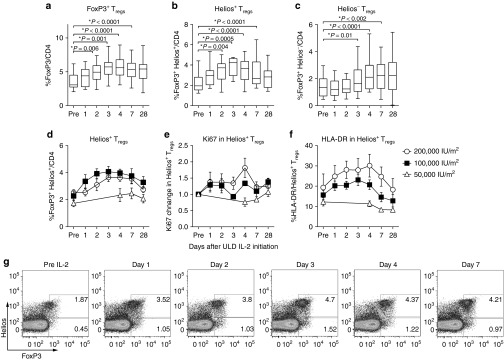

Both Helios positive and negative Tregs are expanded by ULD IL-2

We first analyzed the phenotype of Tregs and NK cells to evaluate whether ULD IL-2 has an impact on lymphocyte subset composition. The proportion of FoxP3+CD4+ Tregs was significantly expanded in all dose cohorts at day 4 (P < 0.0001; Figure 1a). In the Tregs subset analysis, the proportion of Helios+ Tregs was increased by day 2 (P = 0.004; Figure 1b), followed by Helios− Tregs that showed an increase first on day 3 (P = 0.01; Figure 1c). Both subsets of Tregs significantly expanded, peaking at day 4 and remaining higher than baseline at least until day 7. Expansion of Helios+Tregs was primarily observed in the 100,000 and 200,000 IU/m2 IL-2 dose cohorts, whereas healthy donors treated with 50,000 IU/m2 showed modest Helios+Tregs mobilization (Figure 1d). In vivo proliferation of Helios+ Tregs was confirmed by changes in Ki67 expression preferentially in the 100,000 and 200,000 IU/m2 dose cohorts but not observed in 50,000 IU/m2 dose cohort (Figure 1e). HLA-DR expression was significantly increased in FoxP3+Tregs specifically in the Helios+Tregs subset, peaking at day 3 which implies functional activation of Tregs. HLA-DR induction was more prominent in 200,000 IU/m2 cohort compared to the 50,000 or 100,000 IU/m2 cohorts (Figure 1f).

Figure 1.

Chronological changes in Tregs subsets after ultra-low dose (ULD) IL-2. (a) %FoxP3+CD4 Tregs were significantly increased and peaked at day 4 (mean 3.53 ± 1.17% at day 0 versus 5.68 ± 1.56% at day 4; P < 0.0001). (b,c) Helios+FoxP3+Tregs were significantly increased by day 2 (mean 2.19 ± 1.17% at day 0 versus 3.51 ± 1.03% at day 2; P = 0.004) followed by Helios−FoxP3+Tregs (mean 1.36 ± 0.71% at day 0 versus 1.86 ± 1.16% at day 3; P = 0.01). Both subsets of Tregs significantly expanded, peaking at day 4 and remaining significantly higher than baseline until day 7. (d) Expansion of Helios+FoxP3+Tregs was significantly higher when donors received 100,000 and 200,000 IU/m2 IL-2 compared to 50,000 IU/m2 (P < 0.001 and P = 0.01 at day 4 respectively). (e) Ki67 was significantly induced in Helios+FoxP3+Tregs specifically in 100,000 and 200,000 IU/m2 IL-2 compared to 50,000 IU/m2 (P = 0.03 and P = 0.01 at day 4 respectively). (f) HLA-DR was significantly induced in Helios+FoxP3+Tregs specifically in 100,000 and 200,000 IU/m2 IL-2 compared to 50,000 IU/m2 (P = 0.008 and P = 0.04 at day 4 respectively). (g) The representative flow cytometry data showed expansions of FoxP3+CD4 Tregs in both Helios fractions in healthy volunteer receiving ULD IL-2 (200,000 IU/m2).

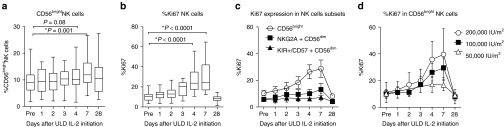

CD56bright NK cells are preferentially expanded by ULD IL-2

In concordance with the Tregs data, the proportion of CD56bright NK cells among total circulating NK cells increased at day 7 (P < 0.0001; Figure 2a), whereas the more mature CD56dimNKG2A+KIR− and CD56dimKIR+CD57+ NK cell subsets remained around baseline (data not shown). The Ki67 proliferation marker further verified a significant in vivo proliferation of NK cells at day 4 (Figure 2b) especially within the subset of CD56bright NK cells compared to CD56dimNKG2A+KIR− and CD56dimKIR+CD57+ NK cell populations (P < 0.0001; Figure 2c). Expansion of CD56bright NK cell subset was dose dependent with the most prominent expansion observed at dose level of 200,000 IU/m2 (Figure 2d).

Figure 2.

Chronological changes in natural killer (NK) cell subsets after ultra-low dose (ULD) IL-2. (a) CD56bright NK cells were significantly increased at day 7 (9.0 ± 4.7% at day 0 versus 12.7 ± 5.8% at day 7; P = 0.001). (b) %Ki67 in NK cell was markedly increased at day 4 (P < 0.0001). (c,d) %Ki67 was significantly induced in CD56bright NK cells compared to CD56dimNKG2A+KIR−, and CD56dimKIR+CD57+ NK populations (26.4 ± 11.4% Ki67+ in CD56bright NK, versus 10.1 ± 7.3% in CD56dimNKG2A+ KIR−NK, 6.1 ± 2.9% CD56dimKIR+CD57+ NK at day 4; P < 0.0001) especially in the cohort of 200,000 IU/m2.

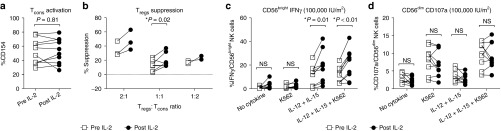

T regs and NK cell function are augmented by ULD IL-2

To determine if IL-2-inducible Tregs and NK cell retain their functions, we next evaluated the in vitro Tregs suppression capacity and NK cell cytokine production comparing in paired samples from the same subject before and after IL-2 administration. Conventional T cells (Tcons: CD3+CD4+CD25lowCD127high) equally expressed CD154 following stimulation with anti-CD3/CD28-coated beads in pre- and post-IL-2 samples (P = 0.86) suggesting ULD IL-2 did not affect T cell receptor–mediated activation of Tcons (Figure 3a). The suppressive capacity of Tregs on CD154 activation of autologous Tcons was significantly increased in post-IL-2 samples at a Tregs:Tcons ratio 1:1 (P = 0.02; Figure 3b). NK cell functional analysis demonstrated significantly increased IFN-γ production following cytokine stimulation of CD56bright NK cells post-IL-2 compared to pre-IL-2 (P = 0.009; Figure 3c), whereas no such effect was observed following stimulation with K562 cells. No difference was observed for CD107a expression by CD56dim NK cells following coculture with K562 or cytokine stimulation when comparing samples collected before and after IL-2 injection (P = 0.75; Figure 3d). These findings indicate that ULD IL-2 not only expanded but also preferentially augmented the function of Tregs and CD56bright NK cell.

Figure 3.

In vitro functions of Tregs and natural killer (NK) cells after ultra-low dose (ULD) IL-2. (a) Tcons (CD3+CD4+CD25lowCD127high) equally expressed CD154 through anti-CD3/CD28-coated bead stimulation in pre- and post-IL-2 samples (CD154 expression 52.3 ± 17.5% pre-IL-2 Tcons versus 52.8 ± 17.9% post-IL-2 Tcon; P = 0.86). (b) The suppressive capacity of Tregs on CD154 activation of autologous Tcons was significantly increased in post-IL-2 samples (% suppression 14.0 ± 6.9% pre-IL-2 versus 19.9 ± 8.8% post-IL-2 at Tregs:Tcons ratio 1:1; P = 0.02). (c) Significantly increased interferon (IFN)-γ productions in post-IL-2 NK cells was observed compared to pre-IL-2 NK cells especially in the CD56brightNK cell subset (mean %IFN-γ production 12.0 ± 2.1% pre-IL-2 versus 21.0 ± 4.2% post-IL-2 with IL-12+IL15 and K562 stimulation; P = 0.009). (d) CD107a expression was not significantly different pre- versus post-IL-2 injections (mean %CD107a expression in CD56dimNK cells, 9.6 ± 3.6% pre-IL-2 versus 9.3 ± 3.7% post-IL-2 with IL-12+IL15 and K562 stimulation; P = 0.75).

IP-10 is increased after ULD IL-2

To determine if ULD IL-2 alters proteomic profiles, 76 cytokines, chemokines, acute phase proteins, and diabetes panel proteins were measured in plasma samples (Supplementary Table S1). Wilcoxon signed-rank test after false discovery rate (FDR) correction demonstrated a significant increase in circulating level of IFN-γ induced protein 10 (IP-10/CXCL10, a ligand for CXCR3) from day 2 through 4 (Supplementary Figure S2). In contrast, circulating levels of other cytokines including IL-2, IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-10, IL-15, and IL-17 remained unchanged. This finding suggests a highly specific biological effect of ULD IL-2.

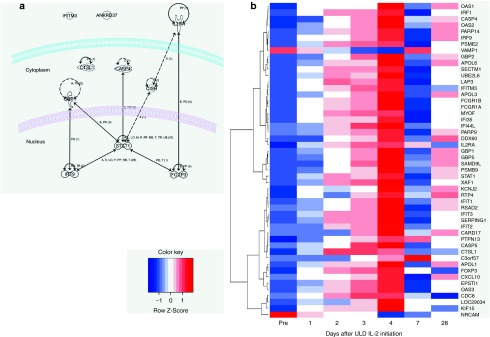

CISH, IL-2RA, and FoxP3 expression are preferentially upregulated by ULD IL-2

Gene expression microarray was performed to identify the different expression profiles in response to the three doses of IL-2 administered to healthy donors. The expression profile of peripheral whole blood before and 4 and 7 days after the first dose of IL-2 (n = 21) was compared using a paired t-test with two-tailed P2 value less than 0.05 corrected by FDR for multiple testing. Four days after the first dose of ULD IL-2, only 10 genes were significantly differentially expressed compared to pre-ULD IL-2 (Figure 4a; Supplementary Table S2). Nine genes were significantly upregulated: CISH, FoxP3, IL2RA, CTLS1, STAT1, GBP1, CASP4, IRF9, IFITM3, whereas only one gene, ANKRD37, was significantly downregulated. On day 7 after IL-2 administration, 14 genes were differentially expressed including IL2RA which remained significantly upregulated 3 days after the last dose of ULD IL-2. Samples from 12 subjects (100,000 and 200,000 IU/m2, n = 6 respectively) were available for further time-course analysis comparing pre- and day 1, 2, 3, 4, and 7 after the first dose of IL-2. The kinetics of expression profiles revealed that FoxP3 and IL2RA were significantly upregulated as early as 2 days through 4 days after the first dose of IL-2 suggesting they represented the most sensitive genes responding to ULD IL-2 (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

Genes differentially expressed by ultra-low dose (ULD) IL-2 in healthy volunteers. (a) Functional annotation of ULD IL-2 related genes: functional relationships are annotated to the genes differentially expressed on day 4 after ULD IL-2 using IPA Ingenuity Path Designer. (b) Time-course analysis of differentially expressed genes after ULD IL-2: hierarchical clustering of genes differentially expressed after ULD IL-2 is shown in a heatmap. Days are represented in the columns and probe sets in the rows.

Thirty-three gene sets were significantly enriched with genes differentially expressed by ULD IL-2 on day 4 (P < 0.005). The gene sets include both innate and adoptive immunity-related pathways. Pathways related to hematopoiesis such as Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor signaling and JAK-Stat signaling were also significantly enriched, consistent with the finding of increased neutrophil and monocyte counts and suggesting ULD IL-2 also targets a broad spectrum of genes outside Tregs and NK cells (Supplementary Table S3). To annotate functional interpretation of the differentially expressed genes by ULD IL-2, we used Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software to compare pre- and day 4 post-ULD IL-2 datasets. Genes modified by ULD IL-2 were significantly enriched in 33 functional categories (P < 0.05) including hematological system development and function, and immune cell trafficking (Supplementary Table S4). In canonical pathway analysis, 29 pathways were enriched in the ULD IL-2 gene set. Gene sets predominantly upregulated by ULD IL-2 occurred in IL-9 signaling, T helper cell differentiation, and interferon signaling, suggesting that ULD IL-2 primarily affects immune-regulating genes. Gene sets predominantly downregulated by ULD IL-2 were found in systemic lupus erythematosus signaling (Supplementary Table S5).

Discussion

This is the first study to prospectively evaluate the global immune signatures of ULD IL-2 in healthy volunteers. ULD IL-2 significantly expanded Tregs in immune-competent healthy volunteers in a similar way to immune-compromised hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients and cancer patients.5,6,13,14,15 We further characterized Tregs subset by Helios, a transcription factor which was previously proposed as a marker of thymus derived Tregs.16 The proposal has been challenged by serial observations reporting Helios may represent the activation or proliferation marker of Tregs17 and can be acquired by peripherally induced Tregs.18 Most recent data, however demonstrated that majority of Tregs were composed by Helios+Tregs in human thymus, cord blood, and at the time of engraftment after allo-SCT favoring the hypothesis that Helios+Tregs can be useful marker for thymus-induced Tregs in clinical settings.19,20,21,22 In our study, both Helios-positive and Helios-negative Tregs, were equally expanded by ULD IL-2. Ki67 expression supported in vivo proliferation of both Helios+Tregs and HLA-DR expression suggested in vivo activation of Helios+Tregs. In vitro function assay demonstrated that Tregs recovered from treated subjects were capable of suppressing autologous Tcons activation, confirming that ULD IL-2 indeed augmented their biological activity. Our findings further support the fact that IL-2 is critically important for Tregs homeostasis.23 The mechanism of selective Tregs expansion by ULD IL-2 may be explained by two scenarios24: preferential IL-2 consumption by Tregs induces cytokine deprivation-mediated apoptosis in Tcons25; and/or that highly sensitive intrinsic IL-2R signaling provides Tregs survival advantages over Tcons cell within thymic or peripheral tissues where available IL-2 is normally limited.26

NK cell subset analysis revealed increased Ki67 expression within the CD56bright NK cell compartment following ULD IL-2, rather than within the more differentiated NK cell subsets such as CD56dimNKG2A+KIR− and CD56dimKIR+CD57+ NK cells.27,28 In vitro analysis further demonstrated that expanded CD56bright NK cells retained functionality, as they produced IFN-γ. CD56bright NK cells are considered more immature than CD56dim NK cells and are known to express the high affinity IL-2 receptor.29 In pioneering work by Fehniger et al.,4 LD IL-2 significantly expanded CD56bright NK cells in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. The mechanism of selective expansion of this particular NK cell subset was hypothesized to result from enhanced differentiation from bone marrow progenitors residing in secondary lymphoid tissues.4,30 A recent in vivo model demonstrated the preferential accumulation of immature NK cells at the site of inflammation in tumor-bearing and chronically infected mice.31,32 IFN-γ produced by NK cell is known to promote antimicrobial immunity through the maturation of dendritic cells and the induction of T helper cell type 1 (TH1) responses.33,34 Therefore, CD56bright NK cells induced by ULD IL-2 may have a beneficial effect to promote antimicrobial immunity, although the exact role of CD56bright NK cells in antitumor activity is unclear.

Most recently, a crosstalk between Tregs and NK cell in the context of IL-2 biology has been reported in several mouse models.32,35,36 Sitrin et al.36 proposed that Tregs function as a cytokine sink, depriving NK cell of IL-2. Gasteiger et al.32 also demonstrated that Tregs restrain the expansion and maturation of immature NK cell in an IL-2-dependent manner. The immune-phenotypic changes observed in our study suggest a similar crosstalk between Tregs and CD56bright NK cell. Importantly, our in vitro function analysis showed cytokine production and cytotoxicity were not impaired in NK cells isolated after ULD IL-2 administration from PBMC, which also contained expanded Tregs. Further research in Tregs-NK cell crosstalk in healthy individuals is needed to clarify the pathways involved.

In order to investigate underlying pathways of ULD IL-2 for this distinct immune-phenotype, we performed a comprehensive cytokine profiling in serum and gene expression microarrays in PBMC. Strikingly, cytokine analysis found only a significant increase in the level of IP-10 (or CXCL10), a chemokine known to be induced by IFN-γ acting as a chemoattractants for monocytes, T cells (including TH1 cells) and NK cells via CXCR3 receptor. IP-10 (CXCL10) is a biomarker associated with various diseases including tuberculosis, autoimmune disease, hepatitis C, and solid organ transplantation.37,38 Recent data suggest that IP-10 (CXCL10) is an important chemoattractant for NK cells, sustaining antitumor effects of IL-2 in a mouse model.39 Thus, ULD IL-2 administration induces a very specific type 1-related immune effect in vivo. Similarly, striking was the finding that gene expression profiling identified only a highly restricted set of 10 transcriptomes differentially expressed after administration of ULD IL-2, considerably fewer than the results of microarray analysis reported in melanoma patients receiving high-dose IL-2.40,41 Notably, the selective coinduction of FoxP3 and IL2RA as early as 2 days after ULD IL-2 was a unique feature in our study and compatible with the immune-phenotype profiles of expanding Tregs defined by IL2RA (CD25)high and FoxP3+ cells. CISH, known to be upregulated by IL-2 in vitro was another distinct gene significantly upregulated after ULD IL-2. CISH is a cytokine inducible SRC homology 2 (SH2) domain protein and belongs to a member of the suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) family which plays an important role in the negative feedback of human cytokine signal transduction. Polymorphisms of CISH gene are associated with the susceptibility to various infectious diseases including bacteremia, malaria, and tuberculosis.42 STAT1, IRF9, GBP1, and IFITM3 are all associated with IFN-γ and gene set enrichment analysis identified that ULD IL-2 activated pathways in the domain of IRF by cytosolic pattern recognition receptors, T helper cell differentiation, and interferon signaling suggesting an activation of type 1-related immune response. In contrast, ULD IL-2 was associated with significant downregulation of genes enriched in systemic lupus erythematosus signaling, suggesting a potential immune-modulating function of ULD IL-2 in autoimmune disease. This gene expression profile pattern implies that ULD IL-2 has two paradoxical but complementary functions: to promote innate and adoptive immunity by IFN-γ signaling and to induce immune suppressive function through FoxP3+Tregs. These functions help to maintain the homeostasis of the immune system in response to infectious pathogens, while preventing resultant excessive autoimmunity.24 Our data are limited to analyze the net effect of ULD IL-2 in whole blood gene expression profile of healthy donors. Gene expression profiles in sorted Tregs, NK cells, and other immune cell compartments would provide further insights of the differential effects of ULD IL-2 in future study.

The immune-modulating properties of ULD IL-2 clearly distinguish it from “conventional” immunosuppressive agents used for hematopoietic SCT, solid organ transplantation, and autoimmune diseases. ULD IL-2 modulates the immune system to restore its normal homeostasis14 rather than generally suppressing the immune system, with the concurrent risk of infectious complications. Most clinical trials have used considerably higher doses of IL-2, and there has hitherto been a lack of information on the relationship between dose and immune-modulating function of ULD IL-2 in man. Our study now defines a lower limit of biological function of subcutaneously administered IL-2 in the region of 100,000 and 200,000 IU/m2. This should guide dose selection for ULD IL-2 in future clinical studies. In the setting of hematopoietic SCT, these results provide the rationale to administer ULD IL-2 in SCT donors to prevent GVHD by increasing Tregs in the stem cell graft. Furthermore, promoting CD56bright NK cell function by ULD IL-2 may reduce the risk of opportunistic infections. Several questions will need to be addressed in a future clinical trial: (i) what is the optimal in vivo expansion and activation of Tregs and NK cells required? (ii) How can we maintain in vivo expanded and activated Tregs and NK cells after adoptive transfer? (iii) What is the impact of Tregs and CD56bright NK cells on antitumor effects? Also the activation of type 1 immune response-related genes parallel to immune suppression genes, FoxP3 and CISH in gene expression microarray analysis may raise the concern of efficacy of ULD IL-2 primed donor graft in GVHD prophylaxis. Nevertheless, the safety profile in healthy individuals determined in this study opens the possibility of administrating ULD IL-2 to donors in settings of well-designed clinical study targeting high GVHD risk SCT such as haploidentical donor SCT.

Materials and Methods

Healthy volunteer study. A phase 1, single-center trial was conducted to evaluate the safety and tolerability of ULD IL-2 in healthy volunteers from December 2011 to April 2013 (NIH protocol 11-H-0268: NCT01445561). Written informed consent including the use of samples for research was obtained from eligible healthy volunteers in accordance with Declaration of Helsinki and the Institutional Review Board of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, NIH. IL-2 (Aldesleukin, Proleukin; Prometheus Laboratories, San Diego, CA) was reconstituted in sterile water for injection, USP and further diluted in 5% dextrose in water, USP to a concentration of 200 µg/ml. Each daily dose was prefilled in a 0.5-ml tuberculin syringe. Enrolled subjects received IL-2 by subcutaneous injection once a day for 5 consecutive days. The study consisted of three dosing cohorts, 50,000, 100,000, and 200,000 IU/m2. Adverse events were monitored daily, and both clinical and laboratory toxicity were graded according to National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE) version 4.03.

Sample collection and storage. Serial blood samples were collected before and 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, and 28 days after initial IL-2 injection in first two dose cohorts (100,000 and 200,000 IU/m2). In subsequent cohorts, which included the 50,000 IU/m2 dose level, samples were collected before and 4, 7, and 28 days after initial IL-2 injection. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient centrifugation (Organon Teknika, Durham, NC) and cryopreserved in RPMI-1640 (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) supplemented with 20% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) and 10% dimethyl sulfoxide according to standard protocol. Serum was obtained by centrifugation of peripheral blood collected in serum separating tubes (SST) (Beckton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). PBMC and plasma samples were stored in liquid nitrogen and −80 °C freezer respectively until further use.

Immunophenotyping by flow cytometry. PBMC samples from all 21 subjects at all time points were available for analysis. Before use, cells were thawed and washed in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS. Cells were stained with violet dead cell-exclusion dye (ViViD; Invitrogen, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and a monoclonal antibody (mAb) panel designed to identify Tregs and NK cell subsets. The following mAb and fluorescent dyes were used: CD3-Brillant Violet 605 (clone OKT3), CD8-Brilliant Violet 570 (clone RPA-T8), CD31-PECy7 (clone WM59), CD45RA-APCCy7 (clone HI100), CD57-APC (clone HCD57), CD127-Brilliant Violet 650 (clone A019D5), KIR3DL1-Alexa Fluor 700 (clone DX-9), Helios-PE (clone 22F6) from Biolegend, San Diego, CA; ViViD amine reactive dye (ViViD: LIVE/DEAD fixable violet dead cell stain), CD14-Pacific Blue (clone TüK4), CD19-Pacific Blue (clone SJ25-C1) from Invitrogen; CD27-PECy5 (clone 1A4CD27), NKG2A-PE (clone z199), KIR2DL2/3-PECy5.5 (clone EB6B), KIR2DL3/3-PECy5.5 (clone GL183) from Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA; CD4-V500 (clone RPA-T4), CD16-V500 (clone 3G8), CD45RO-APCH7 (clone UCHL1), CD56-PECy7 (clone NCAM16.2), CD95-APC (clone DX2), CD197-Alexa Fluor 700 (clone 150503), HLA-DR PerCPCy5.5 (clone L243), Ki67-FITC (clone B56) from BD Bioscience (Franklin Lakes, NJ); FoxP3-Alexa Fluor 647 (clone 236A/E7) from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Tregs subsets were determined within the CD4+ T cell population to identify Helios+Tregs: CD4+FoxP3+Helios+ and Helios− Tregs: CD4+FoxP3+Helios−.16,43 NK cell subsets were determined within CD56+CD3− population using NKG2A, KIR2DL1, KIR2DL2/3, KIR3DL1, and CD57 to identify CD56bright, CD56dimNKG2A+KIR−, and CD56dim KIR+CD57+ NK cells.27,28 Data acquisition was performed using a Becton Dickinson LSRII Fortessa, and data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR). At least 50,000 events per CD4+, CD8+ or CD56+CD3− cell population were acquired to ensure a sufficient number of cells for statistical analysis.

Tregs and NK cell function assays. Paired PBMC samples before and 4 days after IL-2 administration from the 50,000 and 100,000 IU/m2 cohorts (n = 12) were used to evaluate the function of Tregs and NK cells in vitro. PBMCs were labeled with mAbs against CD4, CD25, CD56, CD127, CD14, CD19, CD3, and propidium iodide (Molecular Probe, Eugene, OR). Tregs (CD3+CD4+CD25highCD127low), conventional T cells (Tcons: CD3+CD4+CD25lowCD127high), and NK cells (CD56+CD3−) were sorted in propidium iodide-negative (viable) population on FACS Aria II cell sorter (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Sorting purity for FoxP3+ cells in sorted Tregs was more than 90%. For Tregs suppression assay, Tcons were stained with CellTrace Violet (CTV, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) according to manufacturer's instruction and were then stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28-coated beads (Dynabeads; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at a bead/Tcons ratio of 0.1:1. 20,000 Tcons were then incubated with Tregs at the ratio of 1:1 to 1:2 (responder: suppressor). Anti-CD154 was added at time of incubation (t = 0). After incubation at 37 °C in 5%CO2 for 16 hours, cells were acquired on LSRII Fortessa Cytometer (BD). The proportion of CD154 expression was measured within CTV-labeled Tcons, and the percentage suppression of CD154 was calculated using the formula: %Suppression = 100-(a/b × 100) where a is percentage positive CD154 Tcons in the presence of Tregs and b is percentage positive in the absence of Tregs.44 For NK cell function analysis, sorted NK cells (0.5–1 × 105) were mixed with an equal number of CTV-labeled K562 cells and/or cytokine stimulation (IL-12 10 ng/ml; IL-15 100 ng/ml) and Brefeldin A (GolgiPlug; BD Bioscience).45 After 6 hours incubation at 37 °C in 5%CO2, cells were stained for extracellular expression of CD3, CD56, CD57, CD107a, KIR2DL2/3, KIR2DL3/3 as well as with the ViViD viability dye. Thereafter, cells were permeabilized (Cytofix/Cytoperm Buffer; BD Biosciences) and stained for IFN-γ. Cells were analyzed on a LSR II Fortessa Cytometer.

Cytokine analysis. Seventy-six human cytokines, chemokines, acute phase proteins, and diabetes panel proteins were analyzed using human cytokine multiplexing panel kits (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). All assays were performed according to Bio-Rad kit protocols. Median fluorescence intensities were measured on Luminex 100 instrument (Luminex; Bio-Rad). Standard curves for each cytokine were generated using the premixed lyophilized standards provided in the kits. Cytokine concentrations in samples were determined from the appropriate standard curve using a 5 point-regression to transform mean fluorescence intensities into concentrations using Bio-Plex Manager software version 6. Each sample was run in duplicate, and the average of the duplicate was used as the measured concentration.

Gene expression profiling. Total RNA was extracted from PBMC using a miRNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Universal RNA quality and quantity was estimated using Nanodrop (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE) and Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA). RNA was amplified from 300 ng of total RNA (Ambion WT Expression Kit; Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). cDNA was reverse transcribed with biotinylation and hybridized to the GeneChip Human Gene 1.0 ST Arrays (Affymetrix WTTerminal Labeling Kit; Affymetrix) after fragmentation. The arrays were washed and stained on a GeneChip Fluidics Station 450 (Affymetrix); scanning was carried out with the GeneChip Scanner 3000 and image analysis with the Affymetrix GeneChip Command Console Scan Control.

Statistical analysis. The data from immunophenotyping and functional assays were analyzed with Prism Version 5.04 (GraphPad Sotfware, La Jolla, CA). Statistical significance was accepted if the P value was <0.05 based on one-way analysis of variance and Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test. Affymetrix CEL files were processed with Affymetrix Power Tools for probeset summarization, normalization, and log2-transformation (RMA with sketch quantile normalization). Quality assessment was conducted using R/Bioconductor package “arrayQualityMetrics”,46 and no outlying arrays were found. Array hybridization data were found to be significantly correlated with most probe sets and its effect was removed using linear regression with R “limma” package.47 Prior to further analysis, probesets without annotated gene symbol (using the latest NetAffx annotation) as well as probesets with very low variation (with interquantile range less than 0.15) were filtered out. In addition, probesets associated with multiple genes were also removed. In the case of genes associated with multiple probesets, only one probeset, having the best correlation with first principal component for those probesets across all the samples, was selected (in-house developed R function). After all filtering steps, 15,193 genes were left. To determine genes changing expression from day 0 coherently across individuals, the R/Bioconductor package “limma”47 was used. Subject IDs were included in the model to ensure pair-wise comparison between time points and day 0. P values were adjusted for multiple testing using Benjamini and Hochberg's method to estimate the FDR.48 Stringent cutoffs of 5% FDR-adjusted P value and 0.1 log2-fold-change were used to identify differentially expressed genes. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software (Ingenuity Systems, Redwood City, CA) was used for functional interpretation of gene expression data. Coherent changes in cytokine concentration were analyzed utilizing in-house developed web tool with Perl and R used at the backend. Cytokines with significant response were identified with cutoff of 5% FDR-adjusted P values from Wilcoxon signed rank test.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Figure S1. Chronological changes in absolute peripheral blood counts after ULD IL-2. Figure S2. Changes in serum IP-10 level after ULD IL-2. Table S1. 76 analytes measured in serum cytokine profiling. Table S2. Genes differentially expressed after ULD IL-2 in healthy volunteers. Table S3. Gene sets significantly enriched with genes differentially expressed by ULD IL-2 on day 4. Table S4. Top functional categories of differentially expressed genes. Table S5. Top canonical pathways of differentially expressed genes.

Acknowledgments

We thank H Zhou, R Shi (Center for Human Immunology, NIH, USA) and S Miner, M Franco Colon, and F Chinian (Hematology Branch, NHLBI, NIH, USA) for their technical support. We thank L Bojanowski, V Williams, and A Byrnes (NHLBI, NIH, USA) for their protocol support. We also thank all volunteers who participated in this study. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Study concept and design were performed by S.I., C.B., O.J.M., T.H., P.M., and A.J.B. In vitro experiment and data collection were done by S.I., J.J.M., A.B., J.C., F.M., K.T., K.K., and N.H. Analysis and interpretation of data were done by S.I., M.C., E.W., S.P., N.H., P.M., and A.J.B. Drafting of the manuscript was done by S.I., B.C., M.C., P.M., N.S.Y., and A.J.B. Statistical analysis was performed by S.I., Y.K., F.C., and Z.X. Subject enrollment and clinical data collection were performed by S.I., M.B., P.S., T.H., and A.J.B. N.S.Y. and A.J.B. obtained funding and study supervision. All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

Chronological changes in absolute peripheral blood counts after ULD IL-2.

Changes in serum IP-10 level after ULD IL-2.

76 analytes measured in serum cytokine profiling.

Genes differentially expressed after ULD IL-2 in healthy volunteers.

Gene sets significantly enriched with genes differentially expressed by ULD IL-2 on day 4.

Top functional categories of differentially expressed genes.

Top canonical pathways of differentially expressed genes.

References

- Morgan DA, Ruscetti FW, Gallo R. Selective in vitro growth of T lymphocytes from normal human bone marrows. Science. 1976;193:1007–1008. doi: 10.1126/science.181845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KA. Interleukin-2: inception, impact, and implications. Science. 1988;240:1169–1176. doi: 10.1126/science.3131876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald D, Jiang YZ, Gordon AA, Mahendra P, Oskam R, Palmer PA, et al. Recombinant interleukin 2 for acute myeloid leukaemia in first complete remission: a pilot study. Leuk Res. 1990;14:967–973. doi: 10.1016/0145-2126(90)90109-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehniger TA, Bluman EM, Porter MM, Mrózek E, Cooper MA, VanDeusen JB, et al. Potential mechanisms of human natural killer cell expansion in vivo during low-dose IL-2 therapy. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:117–124. doi: 10.1172/JCI6218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadzadeh M, Rosenberg SA. IL-2 administration increases CD4+ CD25(hi) Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in cancer patients. Blood. 2006;107:2409–2414. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim GC, Martin-Orozco N, Jin L, Yang Y, Wu S, Washington E, et al. IL-2 therapy promotes suppressive ICOS+ Treg expansion in melanoma patients. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:99–110. doi: 10.1172/JCI46266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins MB, Lotze MT, Dutcher JP, Fisher RI, Weiss G, Margolin K, et al. High-dose recombinant interleukin 2 therapy for patients with metastatic melanoma: analysis of 270 patients treated between 1985 and 1993. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2105–2116. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.7.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Topalian SL, Schwartzentruber DJ, Weber JS, Parkinson DR, et al. Treatment of 283 consecutive patients with metastatic melanoma or renal cell cancer using high-dose bolus interleukin 2. JAMA. 1994;271:907–913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooms H, Abbas AK. Revisiting the role of IL-2 in autoimmunity. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:1538–1540. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevach EM. Application of IL-2 therapy to target T regulatory cell function. Trends Immunol. 2012;33:626–632. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy-Nasser AA, Ku S, Melenhorst J, Barrett J, Hazrat Y, Durett AG, et al. 2012Ultra low-dose IL-2 mediated expansion of regulatory T cells as GvHD prophylaxis for recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cellsASBMT Tandem Meeting 2012.

- Kennedy-Nasser AA, Ku S, Castillo-Caro P, Hazrat Y, Wu M-F, Liu H, et al. Ultra low-dose IL-2 for GVHD prophylaxis after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation mediates expansion of regulatory T cells without diminishing antiviral and antileukemic activity. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:2215–2225. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koreth J, Matsuoka K, Kim HT, McDonough SM, Bindra B, Alyea EP, 3rd, et al. Interleukin-2 and regulatory T cells in graft-versus-host disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2055–2066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka K, Koreth J, Kim HT, Bascug G, McDonough S, Kawano Y, et al. Low-dose interleukin-2 therapy restores regulatory T cell homeostasis in patients with chronic graft-versus-host disease. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:179ra43. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka K, Kim HT, McDonough S, Bascug G, Warshauer B, Koreth J, et al. Altered regulatory T cell homeostasis in patients with CD4+ lymphopenia following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:1479–1493. doi: 10.1172/JCI41072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton AM, Korty PE, Tran DQ, Wohlfert EA, Murray PE, Belkaid Y, et al. Expression of Helios, an Ikaros transcription factor family member, differentiates thymic-derived from peripherally induced Foxp3+ T regulatory cells. J Immunol. 2010;184:3433–3441. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akimova T, Beier UH, Wang L, Levine MH, Hancock WW. Helios expression is a marker of T cell activation and proliferation. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e24226. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himmel ME, MacDonald KG, Garcia RV, Steiner TS, Levings MK. Helios+ and Helios- cells coexist within the natural FOXP3+ T regulatory cell subset in humans. J Immunol. 2013;190:2001–2008. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayyoub M, Raffin C, Valmori D. Comment on “helios+ and helios- cells coexist within the natural FOXP3+ T regulatory cell subset in humans”. J Immunol. 2013;190:4439–4440. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1390018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong S, Maiella S, Xhaard A, Pang Y, Wenandy L, Larghero J, et al. Multiparameter single-cell profiling of human CD4+FOXP3+ regulatory T-cell populations in homeostatic conditions and during graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2013;122:1802–1812. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-02-482539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald KG, Han JM, Himmel ME, Huang Q, Kan B, Campbell AI, et al. Response to comment on “helios+ and helios- cells coexist within the natural FOXP3+ T regulatory cell subset in humans”. J Immunol. 2013;190:4440–4441. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1390019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffin C, Pignon P, Celse C, Debien E, Valmori D, Ayyoub M. Human memory Helios- FOXP3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) encompass induced Tregs that express Aiolos and respond to IL-1ß by downregulating their suppressor functions. J Immunol. 2013;191:4619–4627. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setoguchi R, Hori S, Takahashi T, Sakaguchi S. Homeostatic maintenance of natural Foxp3(+) CD25(+) CD4(+) regulatory T cells by interleukin (IL)-2 and induction of autoimmune disease by IL-2 neutralization. J Exp Med. 2005;201:723–735. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malek TR, Castro I. Interleukin-2 receptor signaling: at the interface between tolerance and immunity. Immunity. 2010;33:153–165. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandiyan P, Zheng L, Ishihara S, Reed J, Lenardo MJ. CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells induce cytokine deprivation-mediated apoptosis of effector CD4+ T cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1353–1362. doi: 10.1038/ni1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu A, Zhu L, Altman NH, Malek TR. A low interleukin-2 receptor signaling threshold supports the development and homeostasis of T regulatory cells. Immunity. 2009;30:204–217. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Vergès S, Milush JM, Pandey S, York VA, Arakawa-Hoyt J, Pircher H, et al. CD57 defines a functionally distinct population of mature NK cells in the human CD56dimCD16+ NK-cell subset. Blood. 2010;116:3865–3874. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-282301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björkström NK, Riese P, Heuts F, Andersson S, Fauriat C, Ivarsson MA, et al. Expression patterns of NKG2A, KIR, and CD57 define a process of CD56dim NK-cell differentiation uncoupled from NK-cell education. Blood. 2010;116:3853–3864. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-281675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caligiuri MA, Zmuidzinas A, Manley TJ, Levine H, Smith KA, Ritz J. Functional consequences of interleukin 2 receptor expression on resting human lymphocytes. Identification of a novel natural killer cell subset with high affinity receptors. J Exp Med. 1990;171:1509–1526. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.5.1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freud AG, Becknell B, Roychowdhury S, Mao HC, Ferketich AK, Nuovo GJ, et al. A human CD34(+) subset resides in lymph nodes and differentiates into CD56bright natural killer cells. Immunity. 2005;22:295–304. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vosshenrich CA, García-Ojeda ME, Samson-Villéger SI, Pasqualetto V, Enault L, Richard-Le Goff O, et al. A thymic pathway of mouse natural killer cell development characterized by expression of GATA-3 and CD127. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1217–1224. doi: 10.1038/ni1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasteiger G, Hemmers S, Bos PD, Sun JC, Rudensky AY. IL-2-dependent adaptive control of NK cell homeostasis. J Exp Med. 2013;210:1179–1187. doi: 10.1084/jem.20122571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Fontecha A, Thomsen LL, Brett S, Gerard C, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A, et al. Induced recruitment of NK cells to lymph nodes provides IFN-gamma for T(H)1 priming. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1260–1265. doi: 10.1038/ni1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldszmid RS, Caspar P, Rivollier A, White S, Dzutsev A, Hieny S, et al. NK cell-derived interferon-γ orchestrates cellular dynamics and the differentiation of monocytes into dendritic cells at the site of infection. Immunity. 2012;36:1047–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerdiles Y, Ugolini S, Vivier E. T cell regulation of natural killer cells. J Exp Med. 2013;210:1065–1068. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitrin J, Ring A, Garcia KC, Benoist C, Mathis D. Regulatory T cells control NK cells in an insulitic lesion by depriving them of IL-2. J Exp Med. 2013;210:1153–1165. doi: 10.1084/jem.20122248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suthanthiran M, Schwartz JE, Ding R, Abecassis M, Dadhania D, Samstein B, et al. Clinical Trials in Organ Transplantation 04 (CTOT-04) Study Investigators Urinary-cell mRNA profile and acute cellular rejection in kidney allografts. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:20–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askarieh G, Alsiö A, Pugnale P, Negro F, Ferrari C, Neumann AU, et al. DITTO-HCV and NORDynamIC Study Groups Systemic and intrahepatic interferon-gamma-inducible protein 10 kDa predicts the first-phase decline in hepatitis C virus RNA and overall viral response to therapy in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2010;51:1523–1530. doi: 10.1002/hep.23509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu K, Asakura M, Fujii S. Prolonged antitumor NK cell reactivity elicited by CXCL10-expressing dendritic cells licensed by CD40L+ CD4+ memory T cells. J Immunol. 2011;186:5927–5937. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss GR, Grosh WW, Chianese-Bullock KA, Zhao Y, Liu H, Slingluff CL, Jr, et al. Molecular insights on the peripheral and intratumoral effects of systemic high-dose rIL-2 (aldesleukin) administration for the treatment of metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:7440–7450. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panelli MC, Wang E, Phan G, Puhlmann M, Miller L, Ohnmacht GA, et al. Gene-expression profiling of the response of peripheral blood mononuclear cells and melanoma metastases to systemic IL-2 administration. Genome Biol. 2002;3:RESEARCH0035. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khor CC, Vannberg FO, Chapman SJ, Guo H, Wong SH, Walley AJ, et al. CISH and susceptibility to infectious diseases. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2092–2101. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbas AK, Benoist C, Bluestone JA, Campbell DJ, Ghosh S, Hori S, et al. Regulatory T cells: recommendations to simplify the nomenclature. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:307–308. doi: 10.1038/ni.2554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canavan JB, Afzali B, Scottà C, Fazekasova H, Edozie FC, Macdonald TT, et al. A rapid diagnostic test for human regulatory T-cell function to enable regulatory T-cell therapy. Blood. 2012;119:e57–e66. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-380048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauriat C, Long EO, Ljunggren HG, Bryceson YT. Regulation of human NK-cell cytokine and chemokine production by target cell recognition. Blood. 2010;115:2167–2176. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-238469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffmann A, Gentleman R, Huber W. arrayQualityMetrics–a bioconductor package for quality assessment of microarray data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:415–416. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2004;3:Article3. doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate - a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Roy Stat Soc B Met. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Chronological changes in absolute peripheral blood counts after ULD IL-2.

Changes in serum IP-10 level after ULD IL-2.

76 analytes measured in serum cytokine profiling.

Genes differentially expressed after ULD IL-2 in healthy volunteers.

Gene sets significantly enriched with genes differentially expressed by ULD IL-2 on day 4.

Top functional categories of differentially expressed genes.

Top canonical pathways of differentially expressed genes.