Endogenous rhythmicity likely evolved as a mechanism allowing organisms to anticipate predictable daily changes in the environment (Rutter et al., 2002). Under homeostasis, murine hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) egress is orchestrated by rhythmic γ3 adrenergic signals delivered by the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) that regulate Cxcl12 expression in stromal cells (Mendez-Ferrer et al., 2008). Here, we show that CXCR4 is also regulated under circadian control whose rhythm is synchronized with its ligand CXCL12 to optimize HSC trafficking. These circadian oscillations are inverted in humans compared to the mouse, and continue to influence the yield even when stem cell mobilization is enforced. Our results suggest that the human HSC yield for clinical transplantation may be significantly greater if patients were harvested during the evening compared to the morning.

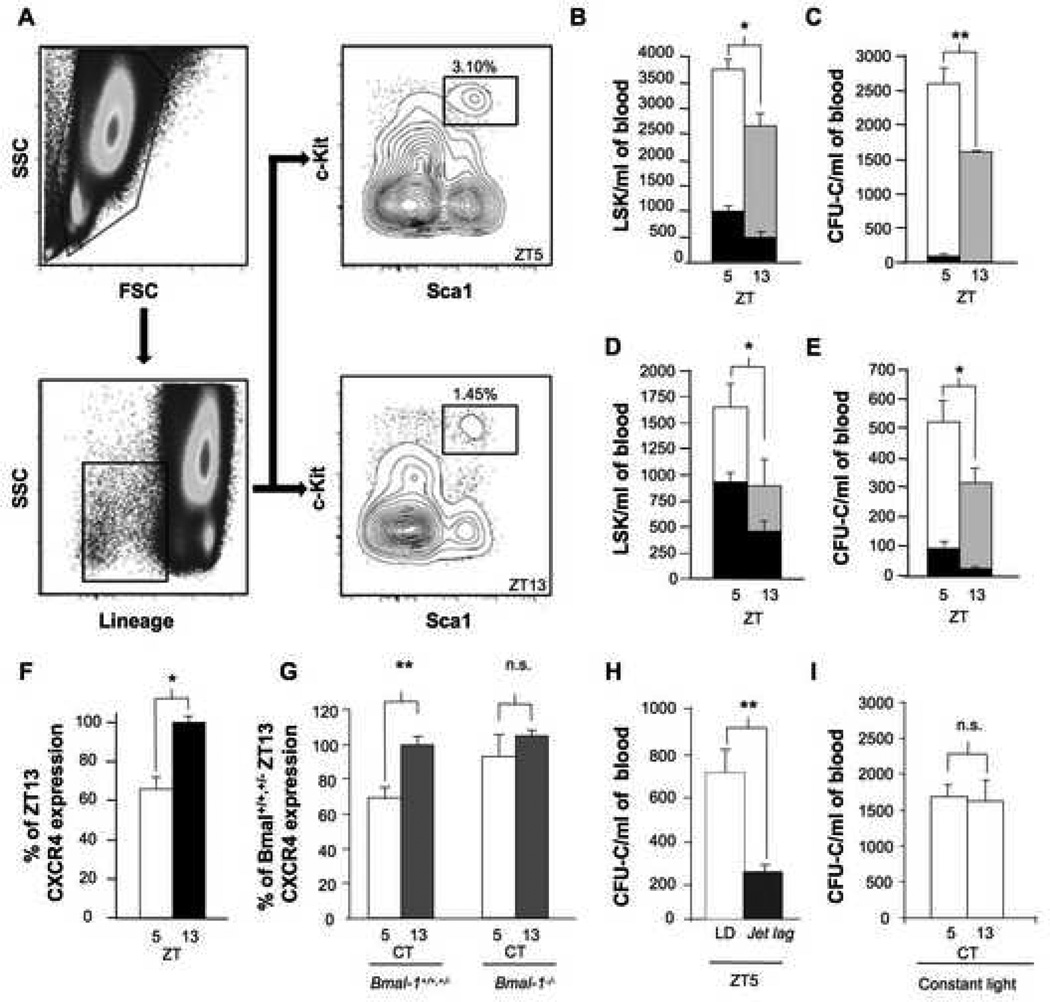

The lowest Cxcl12 expression levels in murine bone marrow coincide with the peak of blood HSCs 5 h after the onset of light (Zeitgeber Time, ZT5), and the highest Cxcl12 levels 8 h later (ZT13) match the lowest circulating HSC counts (Mendez-Ferrer et al., 2008). To assess whether the circadian time can affect enforced mobilization by granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF), the most common stem cell mobilizer used in the clinic, we treated C57BL/6 mice for 4 days (Katayama et al., 2006), and assayed the number of circulating colony-forming progenitors and the stem cell-enriched fraction Lineage− Sca1+ c-kit+ (LSK) cells at the circadian peak and trough (Figure 1A). At both circadian times, G-CSF induced a clear increase in circulating progenitors (Figure 1B and C). In addition, significantly more progenitors and LSK cells were recovered when the blood collection was performed at ZT5 compared to ZT13 (Figure 1B and C). To test whether the circadian difference was sustained when using a rapid mobilizer, we treated C57BL/6 mice at ZT5 and ZT13 with the CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 and assayed progenitors 1 h later (Broxmeyer et al., 2005). We found that the LSK cell counts (Figure 1D) and progenitor yield (Figure 1E) elicited by AMD3100 administration were significantly higher at ZT5 than ZT13. These results thus suggest that the synchronization of blood collection at the peak circadian time can produce greater HSC recovery.

Figure 1. Circadian HSC / progenitor fluctuations in mice modulate G-CSF and AMD3100 mobilization.

A) Representative FACS plot showing the frequency of LSK cells in G-CSF-mobilized murine peripheral blood at ZT5 or ZT13. Live cells were gated and the Lineage− fraction was analyzed to detect the fraction of Sca-1+ and c-kit+ cells. B) Number of LSK cells per ml of blood at ZT5 (white bar) or ZT13 (grey bar) in mice mobilized with G-CSF. The black bars in (B - E) depict the number of LSK cells or CFU-C at ZT5 or ZT13 in the circulation of steady-state mice (Mendez-Ferrer et al., 2008). * p < 0.05, n = 5 mice. Mice received G-CSF (250 μg/kg/day) s.c. every 12 h for 4 days; the last dose of G-CSF was administered 3 h before blood collection. C) Number of CFU-C per ml of blood at ZT5 (white bar) or ZT13 (grey bar) in mice mobilized with G-CSF using the same protocol as in B. ** p < 0.01, n = 10 mice. D) Number of LSK cells per ml of blood at ZT5 (white bar) or ZT13 (grey bar) in mice mobilized with AMD3100. AMD3100 (5 mg/kg) was injected i.p. 1 h before blood collection. * p < 0.05, n = 6–8 mice. E) Number of CFU-C per ml of blood at ZT5 (white bar) or ZT13 (grey bar) in mice mobilized with AMD3100. AMD3100 mobilization was performed as in D. * p < 0.05, n = 10 mice. F) Percentage of CXCR4 expression signal relative to ZT13 (measured by flow cytometry) at ZT5 and ZT13 in bone marrow LSK cells from non-mobilized mice. n=3; *p<0.05. G) CXCR4 expression (normalized to Bmal-1+/+,+/− circadian time (CT) levels) in bone marrow LSK cells collected from Bmal-1+/+,+/− (CT5, n=7; CT13, n=6) or Bmal-1−/− mice (CT5, n=3; CT13, n=4) housed for 1 week in a 12 h dark: 12 h dark regime. CXCR4 oscillations were conserved in Bmal-1+/+,+/− mice (**p < 0.01) in constant darkness but ablated in Bmal-1−/− mice. H) CFU-C per ml of blood at ZT5 in mice housed in a 12 h light: 12 h dark regime (LD) or after a 12h jet lag. To induce the jet lag the light cycle was advanced 12 h at ZT12 (17 h before blood collection at ZT5). AMD3100 mobilization was performed as in D. ** p < 0.01; n=5 mice per group. I) CFU-C per ml of blood at CT5 or CT13 in mice housed in a 12 h light: 12 h light regime for 3 weeks and mobilized with G-CSF as in B. n=5 mice per group. All data are represented as mean ± SEM.

In contrast to the mobilization by G-CSF that reduces CXCL12 synthesis in the bone marrow, the circadian time-dependent efficacy of AMD3100 cannot readily be explained by changes in the microenvironment since the drug targets the CXCR4 receptor on hematopoietic cells. Rhythmic circadian expression of certain signaling molecules and their corresponding receptors has previously been described. For example, the receptors for melatonin (Gauer et al., 1993), cortisol (Schlaghecke and Kley, 1986), EGF (Scheving et al., 1989) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor receptor (Dolci et al., 2003) exhibit rhythmic oscillations. We reasoned that CXCR4 expression might also fluctuate on HSCs to modulate CXCL12 signaling. Flow cytometry analyses of CXCR4 expression on bone marrow LSK cells (Figure 1F) or CD150+CD48− stem cells (Kiel et al., 2005) (Figure S1 A and B) revealed significantly higher CXCR4 expression at ZT13 than at ZT5. CXCR4 fluctuations depended on clock gene expression since CXCR4 did not exhibit any circadian changes on LSK cells derived from Bmal-1−/− mice housed in darkness (Figure 1G). In addition, AMD3100-induced mobilization was significantly altered in mice subjected to a jet lag (defined as a shift of 12 h in the light cycle; Figure 1H). Moreover, disruption of the light cycle by exposure to constant light reduced the yield of G-CSF-induced mobilization (compare Figures 1C and I and see (Mendez-Ferrer et al., 2008)), and abrogated the circadian fluctuations in the yield (Figure 1I). Thus, these results demonstrate that even in situations in which HSC / progenitor egress is pharmacologically enforced, endogenous circadian rhythms controlled by the molecular clock can influence the yield through clock-controlled, synchronized fluctuations of CXCR4 and CXCL12.

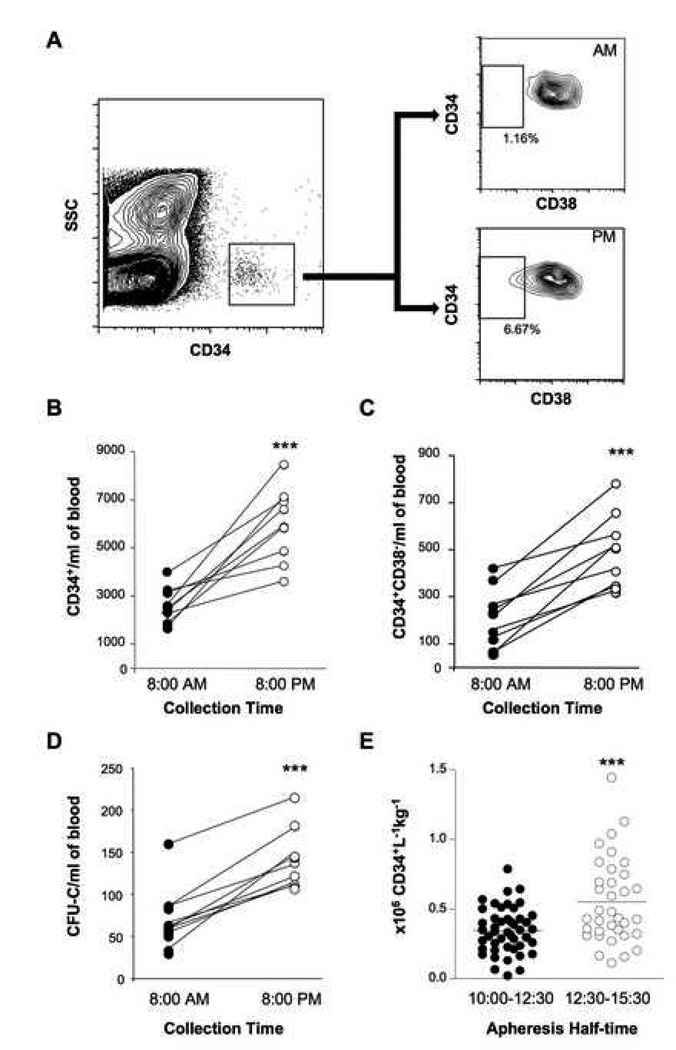

There are conflicting results about rhythms in circulating progenitors in healthy humans with one study showing a peak at 9:00 AM (Ross et al., 1980) and another report with a peak at 3:00 PM (Verma et al., 1980). The internal phase relationships of clock gene expression in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), relative to the light–dark cycle, are conserved across mammals whether the animals are nocturnal or diurnal (Bjarnason et al., 2001; Lincoln et al., 2002; Mrosovsky et al., 2001). Clock gene expression and SCN activity appears to be dictated by light input in all mammals. A classic example is melatonin levels in the pineal gland which peak during the darkness period in both nocturnal rodents and diurnal humans (Buijs et al., 2003). To evaluate whether human circulating HSC rhythms, if present, differ from those in mice, we assayed CD34+CD38− cells and colony-forming progenitor cells in 9 healthy individuals (mean age 33.0 ± 1.4 years—6 males, 3 females) at 8:00 AM and repeated the analyses on the same day at 8:00 PM. As shown in (Figure 2 A-C), both the CD34+ and CD34+CD38− cell subsets were clearly more abundant (>2-fold, p < 0.001) at 8:00 PM than at 8:00 AM in all subjects. Similar results were obtained with the number of colony-forming progenitors (Figure 2D). In fact, all progenitor subsets (CFU-GM, CFU-G, CFU-M and BFU-E and CFU-E) were more abundant in the evening blood compared to the morning (Figure S2). Thus, these results reveal significant oscillations in the number of human blood progenitors, and that the circadian rhythm in humans is inverted when compared to that of the mouse. The maximal release of HSCs at the beginning of the resting period for both species (early night for humans, early morning for mice), further support the intriguing possibility that this phenomenon may contribute to regeneration.

Figure 2. Circadian fluctuations of human progenitors in peripheral blood.

A) Representative peripheral blood FACS analysis from healthy subjects to detect CD34+ CD38− cells in peripheral blood collected at 8:00AM and 8:00PM. Cells were first gated on the CD34+ populations and then analyzed for the presence of CD38− cells. Average number of CD34+ cells (B) and CD34+CD38− cells (C) per ml of blood at indicated times; n=9, ***p<0.001. D) Total colony-forming units in culture (CFU-C) detected in the peripheral blood from same donors; ***p<0.001. E) Number of CD34+ cells recovered per blood volume processed (liters) per weight (kg) of healthy donors that were mobilized using G-CSF (10 µg / kg every morning for 5 days) for allogeneic bone marrow transplantation at Mount Sinai Medical Center between 2001 and 2006. Subjects were grouped according to the apheresis half-time. ***p<0.001.

To evaluate further whether the circadian time could be exploited to increase the yield of HSCs, we analyzed data from 82 healthy donors that underwent G-CSF-induced mobilization for allogeneic bone marrow transplantation between 2000–2006 at Mount Sinai Medical Center. In our center, most apheresis procedures were begun early in the morning but some were in the early PM. We thus divided the patients in two groups according to the collection half-time: those between 10:00 and 12:30 and those in the afternoon between 12:30 and 15:30. We found that the average mobilization yield was significantly higher in the later group (0.35 ± 0.02 vs 0.55 ± 0.05 CD34+ cells / mL / kg; p < 0.001, Figure 2E). Using Spearman correlation test, the mobilization yield correlated very significantly with the time of collection (p<0.001). The effect was valid regardless of the age and gender of the donors (Figure S3). Further, no difference was found between the two groups with regards to the weight of subjects, duration of the apheresis procedure or blood volume processed (Figure S4).

These results suggest that the coordinated circadian expression of CXCR4 and CXCL12 in the bone marrow microenvironment regulates the rhythmic release of HSCs and that these rhythms can impact mobilization when enforced by G-CSF or AMD3100. Although the vast majority of transplantation procedures today are carried out with mobilized stem cells, the stem cell yield is insufficient in up to 40% of patients that have received anti-cancer therapies (Jantunen and Kuittinen, 2008). Intense research effort has been invested to find alternative methods for poor mobilizers. For practical reasons, routine medical procedures are performed in the morning. Since the timing of HSC / progenitor release is inverted in humans compared to mice, we predict that the peak circulating HSC counts during mobilization in humans likely occurs late in the evening. Although prospective clinical studies are needed to ascertain the best time for leukapheresis of G-CSF-mobilized patients, these data suggest that a simple adjustment in the time of harvest may have a significant clinical impact.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Chris Bradfield for providing breeding pairs of Bmal-1+/− mice. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (DK056638). P.S.F. is an Established Investigator of the American Heart Association. M.B. is supported by the Cooley’s Anemia Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bjarnason GA, Jordan RC, Wood PA, Li Q, Lincoln DW, Sothern RB, Hrushesky WJ, Ben-David Y. Circadian expression of clock genes in human oral mucosa and skin: association with specific cell-cycle phases. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:1793–1801. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64135-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broxmeyer HE, Orschell CM, Clapp DW, Hangoc G, Cooper S, Plett PA, Liles WC, Li X, Graham-Evans B, Campbell TB, et al. Rapid mobilization of murine and human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells with AMD3100, a CXCR4 antagonist. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1307–1318. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buijs RM, van Eden CG, Goncharuk VD, Kalsbeek A. The biological clock tunes the organs of the body: timing by hormones and the autonomic nervous system. J Endocrinol. 2003;177:17–26. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1770017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolci C, Montaruli A, Roveda E, Barajon I, Vizzotto L, Grassi Zucconi G, Carandente F. Circadian variations in expression of the trkB receptor in adult rat hippocampus. Brain Res. 2003;994:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauer F, Masson-Pevet M, Skene DJ, Vivien-Roels B, Pevet P. Daily rhythms of melatonin binding sites in the rat pars tuberalis and suprachiasmatic nuclei; evidence for a regulation of melatonin receptors by melatonin itself. Neuroendocrinology. 1993;57:120–126. doi: 10.1159/000126350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jantunen E, Kuittinen T. Blood stem cell mobilization and collection in patients with lymphoproliferative diseases: practical issues. Eur J Haematol. 2008;80:287–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2007.01026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayama Y, Battista M, Kao WM, Hidalgo A, Peired AJ, Thomas SA, Frenette PS. Signals from the sympathetic nervous system regulate hematopoietic stem cell egress from bone marrow. Cell. 2006;124:407–421. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel MJ, Yilmaz OH, Iwashita T, Yilmaz OH, Terhorst C, Morrison SJ. SLAM family receptors distinguish hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and reveal endothelial niches for stem cells. Cell. 2005;121:1109–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln G, Messager S, Andersson H, Hazlerigg D. Temporal expression of seven clock genes in the suprachiasmatic nucleus and the pars tuberalis of the sheep: evidence for an internal coincidence timer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13890–13895. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212517599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez-Ferrer S, Lucas D, Battista M, Frenette PS. Haematopoietic stem cell release is regulated by circadian oscillations. Nature. 2008;452:442–447. doi: 10.1038/nature06685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrosovsky N, Edelstein K, Hastings MH, Maywood ES. Cycle of period gene expression in a diurnal mammal (Spermophilus tridecemlineatus): implications for nonphotic phase shifting. J Biol Rhythms. 2001;16:471–478. doi: 10.1177/074873001129002141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross DD, Pollak A, Akman SA, Bachur NR. Diurnal variation 9 of circulating human myeloid progenitor cells. Exp Hematol. 1980;8:954–960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter J, Reick M, McKnight SL. Metabolism and the control of circadian rhythms. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:307–331. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.090501.142857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheving LA, Tsai TH, Cornett LE, Feuers RJ, Scheving LE. Circadian variation of epidermal growth factor receptor in mouse liver. Anat Rec. 1989;224:459–465. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092240402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlaghecke R, Kley HK. Circadian and seasonal variations of glucocorticoid receptors in normal human lymphocytes. Steroids. 1986;47:287–294. doi: 10.1016/0039-128x(86)90098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma DS, Fisher R, Spitzer G, Zander AR, McCredie KB, Dicke KA. Diurnal changes in circulating myeloid progenitor cells in man. Am J Hematol. 1980;9:185–192. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830090206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.