Abstract

RAS is an oncogene frequently mutated in human cancer. RAS mutations have been reported in 10–15% of cases of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) but they appear to be less frequent among patients with myelodys-plastic syndrome (MDS). The impact of RAS mutations in patients with MDS is unclear. We conducted a retrospective study in 1,067 patients with newly diagnosed MDS for whom RAS mutational analysis was available. Overall, 4% of patients carried mutant RAS alleles. Notably, FLT3 mutations, which were found in 2% of patients, were mutually exclusive with RAS mutations. Patients with RAS mutations had a higher white blood cell count as well as bone marrow blasts compared with patients carrying wild-type RAS. However, no differences were observed between both groups regarding the risk of AML transformation (9% vs. 7%) and overall survival (395 days vs. 500 days, P = 0.057). In summary, RAS mutations are infrequent in patients with MDS and do not appear to negatively impact their outcome.

Introduction

Processes such as cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, self-renewal, cell cycle checkpoint control, DNA repair and genomic stability underpin the pathogenesis of myeloid malignancies. Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) are characterized by the presence of an array of cytogenetic aberrations and mutations involving genes that regulate the homeostasis of all the aforementioned processes [1,2] Mutations in a series of genes have been recently described in patients with AML, including nucleophosmin member 1 (NPM1) [3], fms-related tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) [4–6], KIT [7], RAS [8–11], CCAAT/enhancer-binding-protein-alpha (C/EBPα), TET2 [12], mixed-lineage leukemia (MLL) [13] isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 and 2 (IDH1/2) [14,15], and p53 [9,16]. These gene mutations have not only improved our ability to more accurately predict the prognosis of patients with AML but also have provided novel targets for therapeutic intervention. Unlike AML, where gene mutations are frequently seen, point mutations are rarely present in MDS, with the exception of TET2, which can be detected in approximately 20% of cases. Although the prognostic impact of gene mutations has been extensively studied in patients with AML, limited information is available regarding the prognosis of patients with MDS carrying RAS mutations [17–25]. RAS mutations have been shown to promote cell proliferation and be associated with a higher risk of progression to AML and worse prognosis [20,26,27].

The reported incidence of RAS mutations ranges widely between 2 and 48% [17–25] However, most large cohorts have reported the presence of RAS mutations in approximately 10% of patients [28] In addition, N-RAS has been found mutated and constitutively activated in 10% of patients with AML, whereas K-RAS is mutated in 5% of patients and H-RAS is rarely mutated in AML [29,30] The RAS proto-oncogene belongs to the small GTPase family and exists in three distinct isoforms, N-RAS, K-RAS, and H-RAS [30] Most oncogenic RAS mutations found in human cancers, including AML, occur at codons 12, 13, and 61. However, mutations at alternate codons have also been reported [30,31] RAS regulates the growth and differentiation of many cell types [32]. RAS mutations constitutively activate the RAS signaling pathway by increasing the intracellular levels of RAS GTP, which in turn activates the RAS/Raf/MEK and the RAS/PI3K signaling pathways via interaction with many effectors including Raf proteins, phosphoinositide-3-OH kinase, and RalGDs. In mice, oncogenic N-RAS or K-RAS has been shown to be sufficient to induce AML or a myeloproliferative disorder that resembles chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) [33–35]. This phenomenon has been shown to take place in hematopoietic stem cells rather than in the common myeloid progenitor [36].

DNA hypomethylating agents constitute standard therapy for patients with MDS. The impact of RAS mutational status on response to these agents is unknown [37,38]. In this report, we describe the incidence and type of RAS mutations in 1,067 evaluable patients with MDS diagnosed at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and we analyze the impact of these mutations on prognosis in the context of a variety of MDS therapies, including DNA hypomethylating agents.

Patients and Methods

A retrospective review was done to identify all patients newly diagnosed with MDS at MD Anderson between 2000 and 2009. The analysis followed institutional guidelines. The diagnosis of MDS was based on the French American British classification [39]. Response rate was coded based on the modified International Working Group criteria [40].

RAS, FLT3 [tyrosine kinase domain (TKD) or internal tandem duplication (ITD)], KIT, and JAK2 gene mutational status was assessed by PCR on bone marrow aspirates as previously described [5,26,41]. Cytogenetics were assessed on at least 20 metaphases of each cell type obtained from bone marrow aspirates as previously described [41]. The International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS) was calculated for each patient [42]. Overall survival (OS) was calculated by the Kaplan- Meier method, while the t-test was used to estimate differences between two groups (RAS mutated vs. wild type).

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 1,075 patients with MDS were diagnosed and treated at our institution over the last 10 years. RAS mutational analysis was available in all but eight patients. Forty-three (4%) of 1,067 patients were found to carry a RAS mutation. In the RAS mutated group, the median age was 66 years with 27/43 (63%) being males. The white blood cell count was higher in the RAS mutated group (median 6.8 × 109/dL) compared to the wild type group (3.2 × 109/dL) (P<0.001 by Mann-Whitney median test). A similar trend was observed regarding bone marrow blast burden (9% vs. 5%, P<0.001). Most patients carrying RAS mutations had high-risk MDS [RAEB, RAEB-t, and CMML; 38 (88%) patients]. The rates of leukemic transformation were similar in the RAS wild-type and the RAS mutated groups (7% vs. 9%, P = 0.61). Patient characteristics are shown in Table I.

TABLE I.

Patient and Disease Characteristics According to RAS Mutational Status

| MDS | RAS-wild type | RAS-mutated | All patients |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 1,024 | 43 | 1,067 |

| Age, median | 68 | 66 | 68 |

| Range | 18–94 | 26–84 | 18–94 |

| Sex (No. [%]) | |||

| Male | 676 (66) | 27 (63) | 703 (66) |

| Female | 348 (34) | 16 (37) | 364 (34) |

| AML | 73 (7) | 4 (9) | 77 (7) |

| WBC (×109/L) | 3.3 | ||

| Median range | 3.2 0.3–72.2 | 6.8 0.7–66.4 | 0.3–72.2 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 9.8 | ||

| Median range | 9.8 3–17.5 | 9.4 6.3–13.2 | 3–17.5 |

| Platelets (×109/L) | 73 | ||

| Median range | 75 1–1,040 | 51 1–382 | 1–1,040 |

| Bilirubin | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| Creatinine | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| BM blasts (%) | 5 | 9 | 5 |

| FAB (No. [%]) | |||

| RCMD-R | 47 (5) | 0 | 47 (4) |

| RCMD | 165 (16) | 3 (7) | 168 (16) |

| RARS | 50 (5) | 0 | 50 (5) |

| RAEB-T | 87 (8) | 8 (19) | 95 (9) |

| RAEB | 453 (44) | 18 (42) | 471 (44) |

| RA | 123 (12) | 1 (2) | 124 (12) |

| MDS-U | 18 (2) | 0 | 18 (2) |

| CMML | 68 (7) | 12 (28) | 80 (7) |

| 5q- | 13 (1) | 1 (2) | 14 (1) |

| IPSS (No. [%]) | |||

| High | 142 (14) | 9 (21) | 151 (14) |

| Int-2 | 269 (26) | 13 (30) | 282 (26) |

| Int-1 | 389 (38) | 15 (35) | 404 (38) |

| Low | 201 (20) | 4 (9) | 205 (19) |

| UN | 23 (2) | 2 (5) | 25 (2) |

No.: number of patients, FAB: French American British, IPSS: international prognostic scoring system, UN: unknown.

Thirty-four (79%) out of 43 RAS mutation carriers had an N-RAS mutation. RAS mutations were not detected in RARS, RCMD-RS, or MDS-U, while only one of the patients with RA had an N-RAS mutation. Eighteen (2%) of 1027 patients carried FLT3 mutations (ITD or TKD), which did not overlap with RAS mutations. The JAK2V617F mutation was detected in nine of 37 patients with RAS mutations, including two of three patients with 5q- syndrome. RAS mutations were detected at 4% in patients with diploid cytogenetics and those carrying cytogenetic abnormalities (19/511 and 24/556, respectively). RAS mutations clustered in patients with CMML [12 out of 80 (15%) patients] compared to other MDS groups (4%). Of note, no cases of myeloproliferative CMML (WBC count ≥13 × 109/dL) [27] were found. Five of 68 patients with wild type RAS transformed into AML while no transformations were observed among patients in the RAS mutated group (P = 0.33). Most patients in both groups had diploid cytogenetics. Additional information regarding distribution of mutations based on WHO classification, cytogenetics and CMML and clinical outcomes are shown in Supporting Information Tables SI–SIII.

Impact of RAS mutations on response to therapy

Next, we evaluated the impact of RAS mutations in response to MDS-directed therapy. Patients with MDS carrying wild type RAS alleles achieved similar response rates compared to their RAS mutated counterparts (42% vs 43%) (2 5). A complete response (CR) was attained by five of 14 (36%) patients with mutated RAS compared to a CR rate of 40% observed in the cohort of 236 patients harboring wild type RAS (P 0.74). When analyzing response rates in relation to the type of MDS therapy, patients with mutated RAS did not appear to achieve significantly different response rates compared to those carrying wild-type RAS alleles after therapy with hypomethylating agents (40% vs. 41%), clofarabine (67% vs. 46%), or cytarabine-based therapy (25% vs. 59%) (Supporting Information Table SIV). However, the small number of patients with mutated RAS treated with each type of therapy was too small to draw any definite conclusions.

Impact of RAS mutations on survival

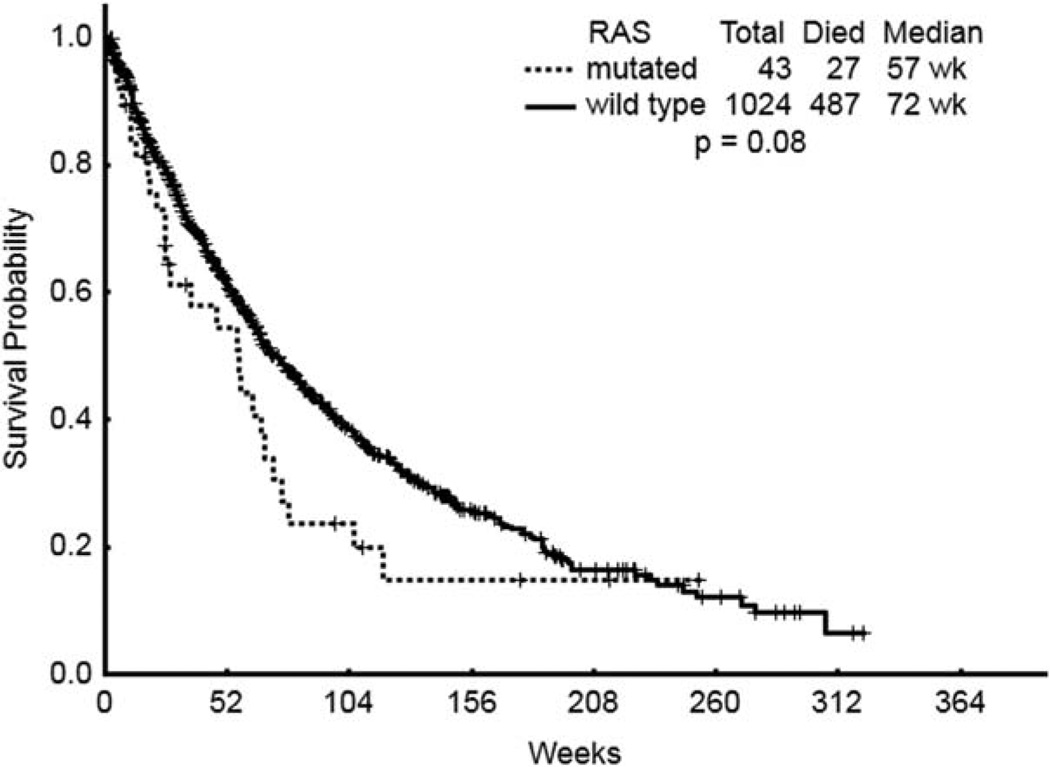

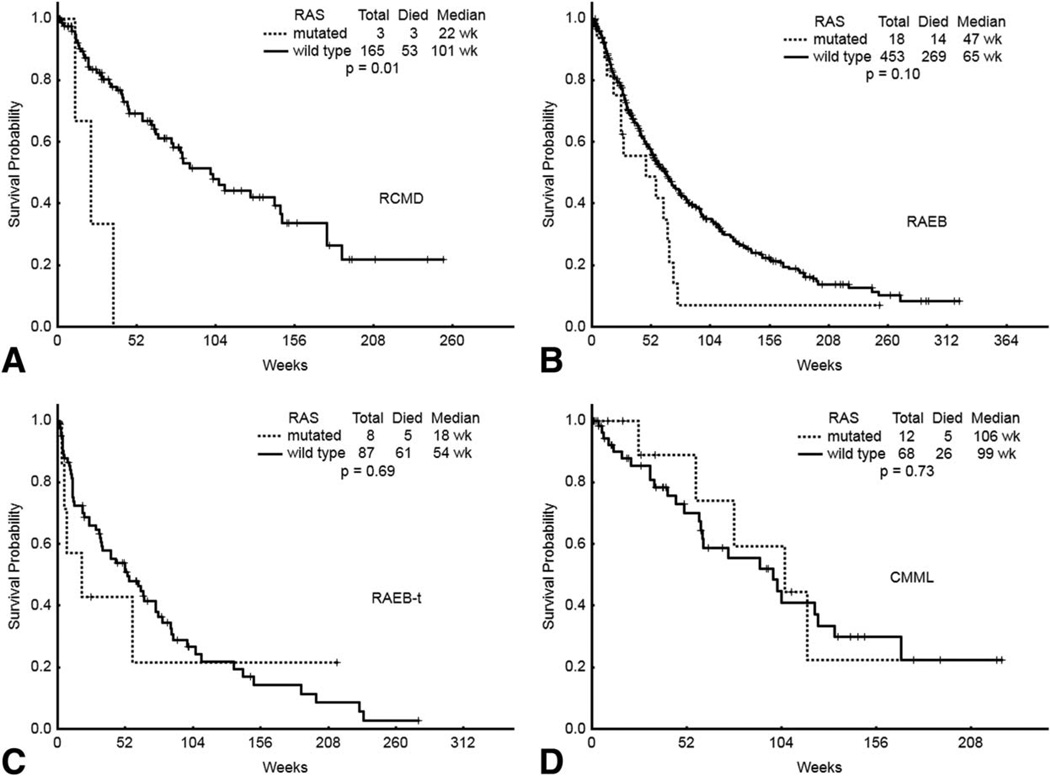

Importantly, in spite of no apparent differences regarding response rates, a trend towards a worse OS was observed among patients in the RAS mutated group compared to that of patients harboring wild type RAS (395 days vs. 500 days, P = 0.057) (Table II and Fig. 1). Furthermore, the presence of RAS mutations was associated with a trend towards a shorter OS across all MDS subgroups compared with their wild type counterparts (Fig. 2). That trend was statistically significant among patients with RCMD carrying RAS mutations (P = 0.00045). However, the importance of this finding is undermined by the small number of patients with RCMD carrying RAS mutations included in the analysis. No differences regarding OS were observed between patients with CMML carrying RAS mutations and those carrying wild type RAS alleles (728 days vs. 687 days, P = 0.44).

TABLE II.

Overall Survival According to RAS Mutational Status

| MDS subtype | RAS wild-type | RAS mutated | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| MDS | 500 | 395 | 0.057 |

| RCMD | 700 | 150 | 0.0045 |

| RAEB | 450 | 325 | 0.13 |

| RAEB-T | 375 | 125 | 0.27 |

| CMML | 687 | 728 | 0.44 |

Overall survival is reported in days.

Figure 1.

OS status for all patients with MDS.

Figure 2.

OS of different MDS subtypes, according to RAS mutational analysis. A) RCMD, refractory anemia with multilineage dysplasia; B) RAEB, refractory anemia with excess blasts; C) RAEB-T, refractory anemia with excess blasts in transformation; D) CMML, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia.

Discussion

Gene mutations have been intensely investigated in myeloid neoplasms, particularly in patients with AML. However, their importance in patients with MDS has not been completely defined. In the present study, FLT3 and RAS mutations were infrequently found (less than 10% of patients) in MDS compared to a reported incidence of approximately 35% for FLT3 mutations among patients with AML. Several gene mutations have been found to be predictive of OS among patients with AML and have been incorporated into models to refine the prognosis of patients with intermediate cytogenetics. However, none of the molecular markers used in AML are currently included in prognostic models for MDS. We herein report the largest cohort of patients with MDS assessed for the presence of RAS mutations to date. RAS mutations were infrequently detected, being present in only 4% of patients, which is not dissimilar to the mutational frequencies previously reported in two other relatively large studies (over 200 patients) of patients with MDS in which RAS mutations were found in 6.3 and 9% of patients, respectively [18,28] As previously reported [28], RAS mutations were more frequent in patients with CMML, with an incidence of 12%. The use of next-generation sequencing technology has allowed the detection of N-RAS and K-RAS mutations in 22 and 12% of patients with CMML, respectively [43], suggesting that RAS mutations in CMML are more frequent occurrences than previously appreciated. Interestingly, none of the patients with CMML in our series were hyperproliferative (i.e., WBC count >12 × 109/dL), in contrast with previous reports [27,44] Gelsi-Boyer et al. [45], reported an incidence of RAS mutations of 46% in patients with myeloproliferative CMML but none in patients with myelodysplastic CMML. However, patients carrying RAS mutations had a higher WBC than those with wild type RAS (6.8 vs. 3.2) as well as a higher bone marrow blast burden (9% vs. 5%) which translated into a higher risk MDS category in the RAS mutated group compared to the wild type group (89% vs. 59%). This is in keeping with previous series reporting a higher incidence of RAS mutations among patients with high-risk MDS [28]. Interestingly, no RAS mutations were detected in low risk MDS with ringed sideroblasts (RARS or RCMD-R). Similar to previously reported series, mutations at codon 12of N-RAS were the RAS mutations more frequently detected (24 of 43 cases), followed by mutations at codon 12 of K-RAS (nine of 24 cases) [20,46]. Typically, RAS mutations clustered preferentially in patients with diploid cytogenetics. FLT3 mutations (ITD and TKD) were uncommon, being detected in only 2% of cases, and they did not overlap with RAS mutations.

No apparent difference was observed regarding response to therapy according to RAS mutational status, with overall response rates in the wild type and mutated RAS groups of 42 and 43%, respectively. Importantly, the presence of RAS mutations did not appear to impair the ability of responding to any type of therapy employed in the management of patients with MDS (e.g., hypomethylating agents, clofarabine, or cytarabine-based therapy). For instance, around 40% of all CRs were attained by patients that received therapy with hypomethylating agents (i.e., azacytidine and decitabine) in both groups. However, solid conclusions regarding the impact of RAS mutations in therapy response could not be confidently drawn given the small number of patients in the RAS mutated group. Importantly, RAS mutational status did not impact significantly patient survival in any of the MDS categories evaluated, although a trend was observed towards worse OS among patients with RAS mutated MDS as a whole, which was statistically significant only among patients with RCMD. However, this latter group only included three patients. Of note, despite the relatively high incidence of RAS mutations observed among patients with CMML, the former did not appear to impact significantly OS compared with the cohort of patients with CMML carrying wild-type RAS alleles.

In summary, RAS mutations are infrequent events in patients with MDS that identify a specific subset of patients with higher WBC count and bone marrow blast burden. The presence of RAS mutations does not appear to significantly impact response or OS compared with their wild type counterparts. However, the use of agents specifically targeting an overactivated RAS pathway (e.g., MEK inhibitors), such as in cases of RAS mutations, might selectively improve the outcomes of this subset of patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grant RP100202 from the Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas, the Ruth and Ken Arnold Fund (GGM), the MD Anderson Cancer Center Leukemia SPORE grant CA100632, and the MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant (CCSG) CA016672.

Footnotes

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Partially presented in abstract form at the 52nd annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, Orlando, FL Dec 4–7th 2010.

Conflict of interest: Nothing to report

Author Contributions

A.A. provided patient care, collected data, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; AQ-C analyzed data and wrote the manuscript; R.L and C.B.R performed molecular work and reviewed the manuscript; S.P. performed statistical analysis and reviewed the manuscript; T.K., G.B., Z.E., E.J., S.F., F.R., J.C., and H.K. provided patient care and reviewed the manuscript; G.G-M. provided patient care, designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Kelly LM, Gilliland DG. Genetics of myeloid leukemias. Annu Rev Genom Hum Genet. 2002;3:179–198. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.3.032802.115046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcia-Manero G. Myelodysplastic syndromes: 2012 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J. Hematol. 2012;87:692–701. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falini B, Mecucci C, Tiacci E, et al. Cytoplasmic nucleophosmin in acute myelogenous leukemia with a normal karyotype. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:254–266. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frohling S, Schlenk RF, Breitruck J, et al. Prognostic significance of activating FLT3 mutations in younger adults (16 to 60 years) with acute myeloid leukemia and normal cytogenetics: A study of the AML Study Group Ulm. Blood. 2002;100:4372–4380. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beran M, Luthra R, Kantarjian H, et al. FLT3 mutation and response to intensive chemotherapy in young adult and elderly patients with normal karyotype. Leuk Res. 2004;28:547–550. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2003.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilliland DG, Griffin JD. The roles of FLT3 in hematopoiesis and leukemia. Blood. 2002;100:1532–1542. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-02-0492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paschka P, Marcucci G, Ruppert AS, et al. Adverse prognostic significance of KIT mutations in adult acute myeloid leukemia with inv(16) and t(8;21): A Cancer and Leukemia Group B Study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3904–3911. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.9500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bacher U, Haferlach T, Schoch C, et al. Implications of NRAS mutations in AML: A study of 2502 patients. Blood. 2006;107:3847–3853. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stirewalt DL, Kopecky KJ, Meshinchi S, et al. FLT3, RAS, and TP53 mutations in elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2001;97:3589–3595. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.11.3589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beaupre DM, Kurzrock R. RAS and leukemia: From basic mechanisms to gene-directed therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1071–1079. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.3.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Radich JP, Kopecky KJ, Willman CL, et al. N-ras mutations in adult de novo acute myelogenous leukemia: Prevalence and clinical significance. Blood. 1990;76:801–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delhommeau F, Dupont S, Della Valle V, et al. Mutation in TET2 in myeloid cancers. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2289–2301. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whitman SP, Ruppert AS, Marcucci G, et al. Long-term disease-free survivors with cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia and MLL partial tandem duplication: A Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. Blood. 2007;109:5164–5167. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-069831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mardis ER, Ding L, Dooling DJ, et al. Recurring mutations found by sequencing an acute myeloid leukemia genome. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1058–1066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0903840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marcucci G, Maharry K, Wu YZ, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 gene mutations identify novel molecular subsets within de novo cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia: A Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. J Clin Oncol. 28:2348–2355. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.3730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bowen D, Groves MJ, Burnett AK, et al. TP53 gene mutation is frequent in patients with acute myeloid leukemia and complex karyotype, and is associated with very poor prognosis. Leukemia. 2009;23:203–206. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakagawa T, Saitoh S, Imoto S, et al. Multiple point mutation of N-ras and K-ras oncogenes in myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myelogenous leukemia. Oncology. 1992;49:114–122. doi: 10.1159/000227023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paquette RL, Landaw EM, Pierre RV, et al. N-ras mutations are associated with poor prognosis and increased risk of leukemia in myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood. 1993;82:590–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitani K, Hangaishi A, Imamura N, et al. No concomitant occurrence of the N-ras and p53 gene mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia. 1997;11:863–865. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2400666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Padua RA, Guinn BA, Al-Sabah AI, et al. RAS, FMS and p53 mutations and poor clinical outcome in myelodysplasias: A 10-year follow-up. Leukemia. 1998;12:887–892. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bowen DT, Frew ME, Hills R, et al. RAS mutation in acute myeloid leukemia is associated with distinct cytogenetic subgroups but does not influence outcome in patients younger than 60 years. Blood. 2005;106:2113–2119. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-0867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kosmider O, Gelsi-Boyer V, Cheok M, et al. TET2 mutation is an independent favorable prognostic factor in myelodysplastic syndromes (MDSs) Blood. 2009;114:3285–3291. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-215814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langemeijer SM, Kuiper RP, Berends M, et al. Acquired mutations in TET2 are common in myelodysplastic syndromes. Nature genetics. 2009;41:838–842. doi: 10.1038/ng.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kosmider O, Gelsi-Boyer V, Slama L, et al. Mutations of IDH1 and IDH2 genes in early and accelerated phases of myelodysplastic syndromes and MDS/myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia. 2010;24:1094–1096. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boultwood J, Perry J, Pellagatti A, et al. Frequent mutation of the polycomb-associated gene ASXL1 in the myelodysplastic syndromes and in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2010;24:1062–1065. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kadia T, Kornblau SM, Kantarjian H, et al. Clinical Characterization and Proteomic Consequences of Mutated Ras in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. ASH Annual Meeting, New Orleans Abstracts. 2009;114:330. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ricci C, Fermo E, Corti S, et al. RAS mutations contribute to evolution of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia to the proliferative variant. Clin Cancer Res. 16:2246–2256. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bacher U, Haferlach T, Kern W, et al. A comparative study of molecular mutations in 381 patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and in 4130 patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2007;92:744–752. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Valk PJ, Verhaak RG, Beijen MA, et al. Prognostically useful gene-expression profiles in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1617–1628. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tyner JW, Erickson H, Deininger MW, et al. High-throughput sequencing screen reveals novel, transforming RAS mutations in myeloid leukemia patients. Blood. 2009;113:1749–1755. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-152157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Le DT, Shannon KM. Ras processing as a therapeutic target in hematologic malignancies. Curr Opin Hematol. 2002;9:308–315. doi: 10.1097/00062752-200207000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schubbert S, Shannon K, Bollag G. Hyperactive Ras in developmental disorders and cancer. Nat Rev. 2007;7:295–308. doi: 10.1038/nrc2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang J, Wang J, Liu Y, et al. Oncogenic Kras-induced leukemogeneis: Hematopoietic stem cells as the initial target and lineage-specific progenitors as the potential targets for final leukemic transformation. Blood. 2009;113:1304–1314. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-134262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Braun BS, Tuveson DA, Kong N, et al. Somatic activation of oncogenic Kras in hematopoietic cells initiates a rapidly fatal myeloproliferative disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:597–602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307203101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parikh C, Subrahmanyam R, Ren R. Oncogenic NRAS rapidly and efficiently induces CMML- and AML-like diseases in mice. Blood. 2006;108:2349–2357. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-009498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sabnis AJ, Cheung LS, Dail M, et al. Oncogenic Kras initiates leukemia in hematopoietic stem cells. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e59. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fenaux P, Mufti GJ, Hellstrom-Lindberg E, et al. Efficacy of azacitidine compared with that of conventional care regimens in the treatment of higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes: A randomised, open-label, phase III study. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:223–232. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70003-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kantarjian H, Oki Y, Garcia-Manero G, et al. Results of a randomized study of 3 schedules of low-dose decitabine in higher-risk myelodysplastic syndrome and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Blood. 2007;109:52–57. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-021162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bennett JM, Catovsky D, Daniel MT, et al. Proposals for the classification of the myelodysplastic syndromes. Br J Haematol. 1982;51:189–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheson BD, Greenberg PL, Bennett JM, et al. Clinical application and proposal for modification of the International Working Group (IWG) response criteria in myelodysplasia. Blood. 2006;108:419–425. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hirsch-Ginsberg C, LeMaistre AC, Kantarjian H, et al. RAS mutations are rare events in Philadelphia chromosome-negative/bcr gene rearrangement-negative chronic myelogenous leukemia, but are prevalent in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Blood. 1990;76:1214–1219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Greenberg P, Cox C, LeBeau MM, et al. International scoring system for evaluating prognosis in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 1997;89:2079–2088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kohlmann A, Grossmann V, Klein HU, et al. Next-generation sequencing technology reveals a characteristic pattern of molecular mutations in 72.8% of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia by detecting frequent alterations in TET2, CBL, RAS, and RUNX1. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3858–3865. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Onida F, Beran M. Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia: Myeloproliferative variant. Curr Hematol Rep. 2004;3:218–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gelsi-Boyer V, Trouplin V, Adelaide J, et al. Genome profiling of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia: Frequent alterations of RAS and RUNX1 genes. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:299. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Kamp H, de Pijper C, Verlaan-de Vries M, et al. Longitudinal analysis of point mutations of the N-ras proto-oncogene in patients with myelodysplasia using archived blood smears. Blood. 1992;79:1266–1270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.