Abstract

Introduction:

Breast cancer is an international health problem in the world over. Mammography screening behavior has critical role in early detection and decreasing of its mortality. Educational programs play an important role in promoting breast cancer screening behaviors and women health. Health belief models (HBM) is the most common models that have been applied in Mammography screening behaviors. The aim of this study was to determine the effect of breast cancer screening education using HBM on knowledge and health beliefs in 40 years women and older.

Materials and Methods:

In this Population-based controlled trial, 290 women of 40 years and older were divided randomly into experimental and control groups. Health beliefs determined using the Persian version of Champion's health belief model scale (CHBMS). Questionnaires were completed before and 4 weeks after intervention. Four educational sessions were conducted each session lasting 90 min by lecturing, group discussion, showing slide and educational film based on HBM constructs. The obtained data were analyzed by SPSS (version 18) and statistical test at the significant level of α = 0.05.

Results:

Mean scores of perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, barriers and self-efficacy of mammography and health motivation in the experimental group had significant differences in comparison with the control group after educational intervention (P ≤ 0.001).

Conclusion:

The results of this study have confirmed the efficiency of educational intervention based on HBM in increasing of knowledge and health beliefs about breast cancer and mammography screening behavior. Hence, implementing appropriate educational programs with focus on benefits of Mammography in early detection of breast cancer and creating positive motivation for health among women, can increase their practice of having mammography screening.

Keywords: Breast cancer, education intervention, health belief model, mammography screening

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is a major health challenge in the world over. It is the most commonly cancer and a leading cause of death among women. Breast cancer incidence rate is rapidly increasing, especially in developing countries.[1,2] During the last 30 years, the incidence of breast cancer has doubled in Iran[3] and is now ranked as the first among diagnosed cancers in women.[4] Therefore, it is one of the most important women's health problems in Iran and should be managed with preventive and screening measures.

Screening prevention plays an important role in early detection of breast cancer and decreasing its mortality rates.[5] The recommended screening approaches for early diagnosis of breast cancer are mammography, clinical breast examination (CBE) and breast self examination (BSE).[6,7] Both the Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education and the American Cancer Society (ACS) recommended annually mammography screening in their guidelines for early detection of breast cancer.[8,9]

Annual mammography screening is the best technique to discover tumor before signs and symptoms appear and can prompt effective treatment.[9,10] Also, the ACS recommended that women should become inform about the benefits, barriers and potential harmful of regular screening.[11] Iranian ministry of health aims to increase mammography use among women aged 40 years and over for early detection of breast cancer. Research findings showed that delay in presentation of breast cancer in developing countries, like Iran was contributed to low knowledge level, lack of screening program, lack of educational program, late and poor access to health care facilities.[1,3]

Studies revealed that behavior-based interventions can help women overcome their personal barriers, encourage them to seek mammography screening and maintain regular mammography screening behavior.[12,13,14] The health belief model (HBM) is one of the models that widely used as a guiding framework for health behavior interventions, especially mammography screening behavior.[15] Therefore, in this study the HBM has been applied as the theoretical framework to develop an educational intervention about mammography screening and evaluate effects of education on knowledge and health beliefs.

The HBM is a psychosocial model, which originally developed in 1950s and updated in the 1980s.[16] According to HBM, women will be more to perform mammography screening behavior if they feel susceptible to breast cancer (perceived susceptibility), believe breast cancer is a serious disease (perceived severity), perceive more benefits from mammography with regard to mammography barriers, have higher confident for obtaining mammography and receive a cue to action.[15,17]

Studies have indicated that perceived susceptibility and severity are associated with enhance of breast cancer knowledge and perceived benefits and barriers have the positive correlation to behavior change.[18,19] Thus, appropriate educational interventions can promote women knowledge level, change their attitude and health belief about breast cancer and mammography screening and finally effects on their performance toward mammography use. Although, women's knowledge and health belief of breast cancer screening behavior have been studied in Iran and few educational interventions undertook to increase knowledge, health belief and behavior of mammography use,[16,20,21,22,23,24] none of them relied upon Farsi version of champion health belief model.

In addition, these studies are targeted in special group of women and none have evaluated health beliefs related to mammography screening with Farsi version of champion health belief model. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the effectiveness of breast cancer educational intervention based on HBM in Iranian women. The researchers hypothesized that women who received this breast cancer educational program would establish significant difference in knowledge and attitude about breast cancer comparison of women in control group.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and sampling method

A Population-based controlled trial design was used to determine the effectiveness of breast cancer educational intervention. Participants were women of 40 years and older, whom were recruited by telephone interview procedures that have been described in detail elsewhere.[25] In short, eligible women were identified from a population-based survey which was performed in Isfahan, a city located in central region of Iran between March 2011 and June 2011.

Three hundred and eighty four women aged 40 years and over who had not personal history of breast cancer, tendency to participant in the survey and being able to speak, were interviewed by telephone. From 384 eligible women, 290 women agreed to participate in educational program (response rate of 75.52%). Participants were randomly assigned to an intervention or control groups.

A sample size of 121 women in each group would be required to confirm a minimum significant increase in mammography screening of 50%, a power of 90% with a 0.05 two-sided significant level. Based on a predicted attrition rate of 20%, our sample was to randomly assign 145 women in each group.

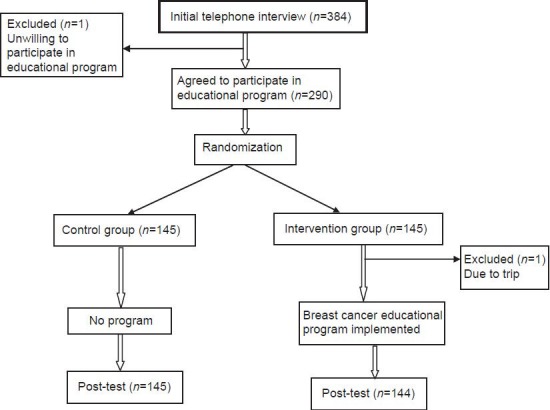

From 290 women who at first agreed to participate in education program, one of them in intervention group dropped out due to trip. As a result, 144 women in intervention group and 145 women in the control group were participated in this study [Figure 1]. All study activities were approved by the ethical committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study participants

Measurement

Data collection instrument in this study include three sections: Sociodemographic questions, knowledge about breast cancer and questions about the HBM scale.

Information such as age, marriage age, age of first birth, level of education, current marital status, number of child, breastfeeding duration, menopausal status, health insurance coverage, monthly household income and ever heard or read about breast cancer provided the sociodemographic variables. To measure the women's level of knowledge of breast cancer, we used 11 questions which were developed by the researchers based on an extensive review of the published studies. These questions were about breast cancer risk factors (6 items), sign and symptoms of breast cancer (1 item), early detection of breast cancer and, mammography screening (4 items). For all of questions, except of symptom of breast cancer, the answers were “regeneration”, “regeneration” and “do not know”. For each question, true response was scored as 1, false and do not know as 0. So, for each woman, a score between 0 and 11 was computed.

To assess beliefs and attitudes about breast cancer and mammography, we utilized the champion health belief model scale (CHBMS). It is a commonly used scale to measure HBM components. The CHBMS was developed in 1984 and it has been revised three times. The latest version of the CHBMS was adapted for Iranian use by Taymoori and Berry.[26] In this study, we used Farsi version of the CHBMS after allowance was obtained from authors. This scale includes 61 items with 8 subscales. However, only six subscales were used in this survey.

The HBM subscales, which used in this study were the perceived susceptibility (3 items), perceived severity (7 items) to breast cancer, health motivation (7 items), benefits of mammography (6 items), barriers of mammography (10 items) and mammography self-efficacy (3 items). All the items had five response choices ranging strongly disagree = 1 to strongly agree = 5. Higher scores express more agreement with health beliefs except for barriers to mammography. Each subscale was calculated separately, and therefore, six different scores were obtained for each subject. Reported Cronbach alpha for Farsi version of CHBMS ranged from 0.72-0.84.[26]

Educational intervention

Participants in the intervention group received the breast cancer educational program. Because of all of women could not simply participate in educational program, this educational program was conducted in 11 health centers in urban area of Isfahan, Iran. The educational intervention consisted of four teaching sessions and each session lasting 90-120 min which was organized for small groups of 10 to 15 women.

The content of educational programs included basic information regarding breast cancer facts and figures, breast cancer epidemiology, breast anatomy, risk factors of breast cancer development, signs and symptoms, important early detection, recommended screening methods, guidelines for mammography screening, role of mammography in early diagnosis breast cancer and presentation list of governmental hospital where can get mammography. In addition to this information, each group received specific messages related to health motivation, susceptibility to breast cancer, the perceived benefits and barriers of mammography and perceived self-efficacy based on HBM.

Problem-solving approach was used in educational sessions. This approach allowed women to learn, encourage, and empower to have mammogram and take care of their health. During educational sessions, teaching methods such as PowerPoint presentation, educational film, group discussion, brain storming, question and answer and two pamphlets entitled “Know more about breast cancer” and “Mammography, useful test for early detection of breast cancer” were used. At the end of each session, the educator reviewed the important topics of this session and the women were encouraged to ask their questions about mentioned issues and their misperception were corrected.

Four weeks after the educational intervention, post-test was implemented by telephone interview in both of the intervention and control group. In intervention group, verbal and written consent and in control group only verbal consent obtained.

Data analysis

The obtained data were analyzed by SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois). Descriptive analyses were utilized to summarize the subject's variables. Chi-square, t-test and paired t-test were used in the data analysis. In all of the tests, the level of significant was considered as α = 0.05.

RESULTS

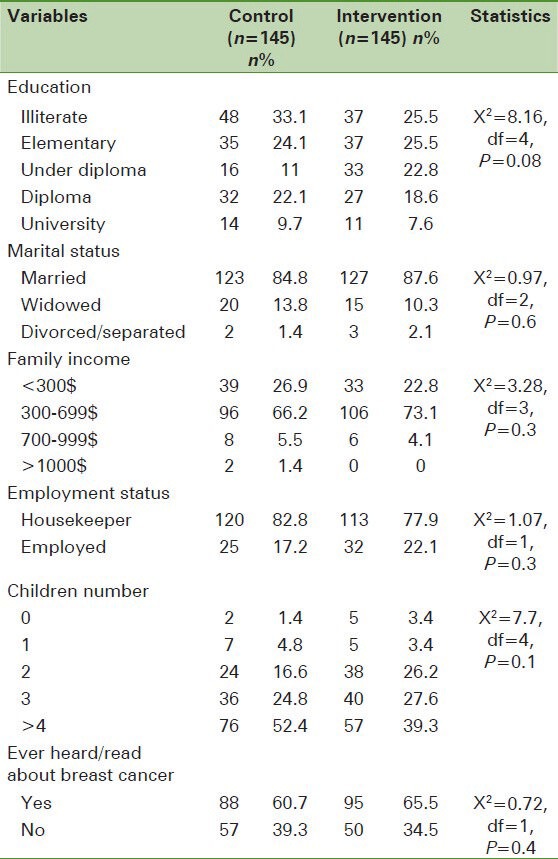

The mean and standard deviation of women's age was 50.48 ± 6.81 years in intervention group and 52.63 ± 8.97 years in control group. [Table 1], presents the demographic and baseline characteristics of the intervention and control groups. The results showed that there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in education, marital status, employed status, income, and child number and ever heard or read about breast cancer. The majority of the subjects were illiterate (33.1% in the intervention group and 25.5% in the control group), more than two-thirds of them were married and housekeeper in the two groups. The most of participants reported family monthly income as 300-700$ (73.1% in intervention group and 66.2% in control group). In addition, 60.7% women in intervention group and 65.5% in control group stated that they had read or heard about breast cancer.

Table 1.

Characteristics of samples by study group

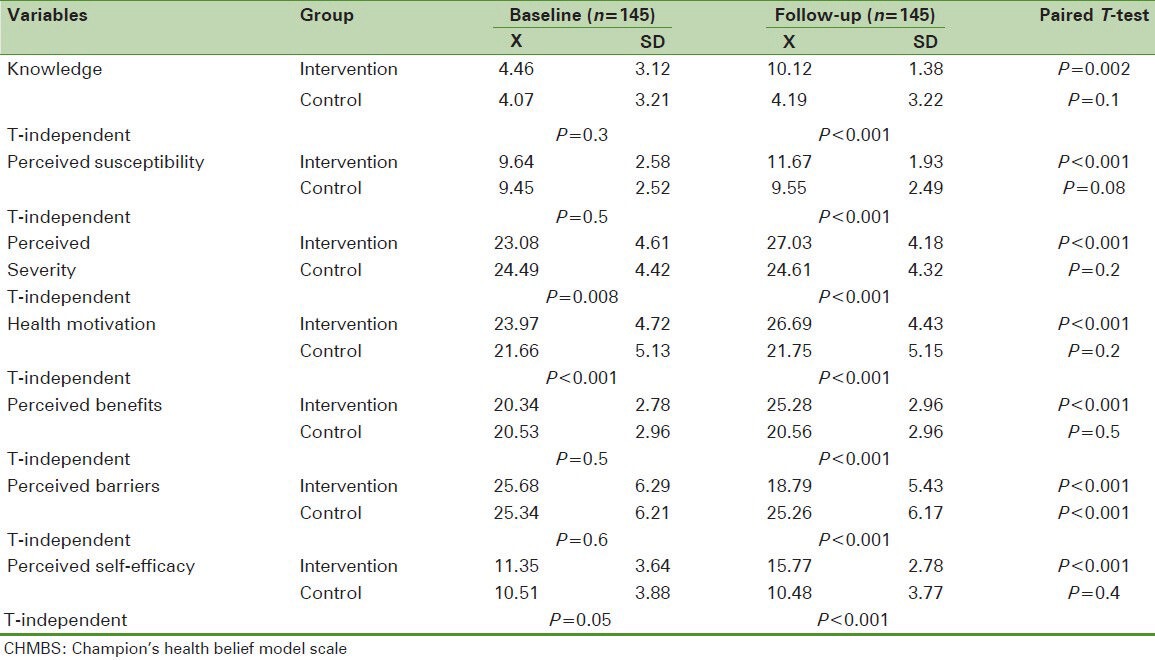

The results of comparing the mean scores of knowledge and HBM subscales before and after educational intervention within and between intervention and control groups are described in [Table 2]. Independent T-test showed that before intervention, the mean scores of knowledge and health beliefs in the two groups were similar in almost all subscales except to perceived severity and health motivation. Four weeks after educational intervention, the mean scores of knowledge, perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, health motivation, perceived benefits of mammography and perceived self-efficacy of mammography were significantly higher in the intervention group. Also, the mean scores of perceived barriers of mammography decreased in the intervention group.

Table 2.

Comparison of mean scores of knowledge and CHBMS subscales by time and group

DISCUSSION

This study was designed to evaluate the effectiveness of a breast cancer educational intervention based on HBM on knowledge and health beliefs of women related to breast cancer and mammography screening. The study results indicated a significant increase in knowledge of intervention group about breast cancer and mammography screening after educational intervention. This difference in mean scores of knowledge between two groups can likely be attributed to using of a divers, efficient, flexible and attractive educational intervention in the current study. The finding of this study is inconsistent with other reports regarding the effectiveness of education on knowledge using group education,[27,28] video and group education,[29,30] video, group education plus pamphlet or flip chart[16,24,31,32,33] and peer education.[17,34] This result is important because of previous studies have demonstrated that knowledge is an important element in the HBM[29,32,35,36] and also have significant impact on increasing of mammography screening behavior.[29,32,37,38,39]

In this study, women's beliefs regarding to breast cancer and mammography screening behavior increased 4 weeks after educational intervention in all of the HBM components. According to HBM, women's perception of their susceptibility to breast cancer and the severity of the disease were associated with their knowledge about disease.[10] The susceptibility referred to subject's individuals beliefs on vulnerability of the breast cancer. Women who received the educational intervention, their perceived susceptibility of having breast cancer increased in comparison with the control group. This finding is in accordance with the earlier studies.[16,24,30,32,40,41] In contrast with our study, Ceber's study reported the absence of significant difference in perceived susceptibility between experimental and control groups.[29]

Perceived severity about breast cancer reflects “the women's acceptance level in their life after having breast cancer”.[17] Similar to our study, results of several studies showed positive change in mean scores of perceived seriousness after education.[16,17,24] It can conclude that educational intervention has a positive effect on subject's perceived threat about breast cancer. In the present study, the scores of health motivation and benefits of mammography were significantly improved in intervention group after receiving the educational intervention. Previous studies have found similar results.[17,24,29,30,31]

According to HBM, women who perceive more benefits and lower barriers from mammography, more likely perform mammography screening behavior.[19] Results indicated that the educational intervention in this study increased perceived benefits and decreased perceived barriers significantly in intervention group comparison to control group. In a study from Turkey, peer education increased perceived benefits of mammography and lowered the perceived barriers of mammography.[17] Contrary to our study, in Hall et al. study, mammography benefits and mammography barriers were not significantly different between the control and experimental groups.[32]

Self-efficacy was found significantly higher in intervention group. After educational intervention, subjects had more confident to having mammography screening in intervention group. In other words, women perceived ability successfully perform mammography screening behavior. This finding is accordance with HBM and finding of previous studies.[29,32,36,38]

In general, educational intervention based on Farsi version of CHBMS in this study was successful as primary strategy to increase knowledge and improve of women's health beliefs about breast cancer and mammography screening.

Limitation

Although, the current study showed positive effectiveness on knowledge and health belief about breast cancer and mammography, however several limitations must be addressed. In our study, knowledge and women's beliefs about mammography were investigated only 4 weeks after educational intervention. Thus, we could not examine practice of mammography in this time period. A long-term follow-up could assess knowledge, attitude and practice of subjects more carefully over time. We are planning to carry out such study as well. Also, because of using the HBM, we could not assess the social factors such as social norms in this study. Thus, concomitantly using the theory of planned behavior (TPB) and HBM is recommended.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Isfahan University of Medical Sciences

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Seedhom AE, Kamal NN. Factors affecting survival of women diagnosed with breast cancer in El-Minia governorate, Egypt. Int J Prev Med. 2011;2:131–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sim HL, Seah M, Tan SM. Breast cancer knowledge and screening practices: A survey of 1,000 Asian women. Singapore Med J. 2009;50:132–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Babu GR, Samari G, Cohen SP, Mahapatra T, Wahbe RM, Mermash S, et al. Breast cancer screening among females in iran and recommendations for improved practice: A review. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:1647–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kolahdoozan S, Sadjadi A, Radmard AR, Khademi H. Five common cancers in Iran. Arch Iran Med. 2010;13:143–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American College of Obestricts and Gynecologist. Practice bulletin no. 122: Breast cancer screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(2 Pt 1):372–82. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31822c98e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gursoy AA, Ylmaz F, Nural N, Kahriman I, Yigitbas C, Erdol H, et al. A different approach to breast self-examination education: Daughters educating mothers creates positive results in Turkey. Cancer Nurs. 2009;32:127–34. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181982d7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sandra A, Wendy S. 5th ed. Canada: Jones and Burtlett Publishers; 2009. Essential concepts for healthy living; pp. 363–6. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mousavi SM, Harirchi I, Ebrahimi M, Mohagheghi MA, Montazeri A, Jarrahi AM, et al. Screening for breast cancer in Iran: A challenge for health policy makers. Breast J. 2008;14:605–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2008.00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2012. American Cancer Society, (ACS). Cancer Facts and Figures 2012; pp. 9–10. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farmer D, Reddick B, D’Agostino R, Jackson SA. Psychosocial correlates of mammography screening in older African American women. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34:117–23. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.117-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canbulat N, Uzun Ö. Health beliefs and breast cancer screening behaviors among female health workers in Turkey. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12:148–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Russell KM, Champion VL, Monahan PO, Millon-Underwood S, Zhao Q, Spacey N, et al. Randomized trial of a lay health advisor and computer intervention to increase mammography screening in African American women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:201–10. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin ZC, Effken JA. Effects of a tailored web-based educational intervention on women's perceptions of and intentions to obtain mammography. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19:1261–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim J, Menon U, Wang E, Szalacha L. Assess the effects of culturally relevant intervention on breast cancer knowledge, beliefs, and mammography use among Korean American Women. J Immigr Minor Health. 2010;12:586–97. doi: 10.1007/s10903-009-9246-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Inc Pub; 2008. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice; pp. 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moodi M, Mood MB, Sharifirad GR, Shahnazi H, Sharifzadeh G. Evaluation of breast self-examination program using Health Belief Model in female students. J Res Med Sci. 2011;16:316–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gozum S, Karayurt O, Kav S, Platin N. Effectiveness of peer education for breast cancer screening and health beliefs in eastern Turkey. Cancer Nurs. 2010;33:213–20. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181cb40a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Champion V, Springston J, Zollinger T, Saywell R, Jr, Monahan P, Zhao Q, et al. Comparison of three interventions to increase mammography screening in low income African American women. Cancer Detect Prev. 2006;30:535–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garza MA, Luan J, Blinka M, Farabee-Lewis RI, Neuhaus CE, Zabora JR, et al. A culturally targeted intervention to promote breast cancer screening among low-income women in East Baltimore, Maryland. Cancer Control. 2005;12(Suppl):34–41. doi: 10.1177/1073274805012004S06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hadizadeh F, LatifNezhad R. The effect of a training curriculum on attitude of female students about breast self-examination by using health belief model (HBM) JBUMS. 2005;12:25–30. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghanbari A, AtrkarRoshan Z. A comparison between education by compact disc and booklet on learning outcome in nursing and midwifery students about breast self-examination. Journal of Medical Faculty Guilan University of Medical Sciences. 2004;12:39–3. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karimi H, Sh S. Effect of breast self-examination (BSE) education on increasing women's knowledge and practice. Ramsar Journal of Babol University of Medical Sciences. 2005;7:68–1. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vaez Zadeh N, Esmaili Z. A comparative study on the effect of video and individual instruction on self examination of breast on performance of referring women to health service centers of Gaemshahr township, in 2000. Journal of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences. 2001;11:22–6. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hatefnia E, Niknami Sh, Mahmoudi M, Ghofranipour F, Lamyian M. The Effects of health belief model education on knowledge attitude and behavior of Tehran pharmaceutical industry employees regarding breast cancer and mammography. Behbood The Scientific Quarterly. 2010;14:42–53. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moodi M, Rezaeian M, Mostafavi F, Sharifirad GR. Determinants of mammography screening behavior in Iranian women: A population-based study. JRMS. 2012;17:33–42. [In press] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taymoori P, Berry T. The validity and reliability of Champion's Health Belief Model Scale for breast cancer screening behaviors among Iranian women. Cancer Nurs. 2009;32:465–72. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181aaf124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allen JD, Stoddard AM, Mays J, Sorensen G. Promoting breast and cervical cancer screening at the workplace: Results from the Woman to Woman Study. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:584–90. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.4.584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ortega-Altamirano D, Lopez-Carrillo L, Lopez-Cervantes M. Strategies for teaching self-examination of the breast to women in reproductive age. Salud Publica Mex. 2000;42:17–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ceber E, Turk M, Ciceklioglu M. The effects of an educational program on knowledge of breast cancer, early detection practices and health beliefs of nurses and midwives. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19:2363–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Avci IA, Gozum S. Comparison of two different educational methods on teachers’ knowledge, beliefs and behaviors regarding breast cancer screening. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2009;13:94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Secginli S, Nahcivan NO. The effectiveness of a nurse-delivered breast health promotion program on breast cancer screening behaviours in non-adherent Turkish women: A randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;18:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hall CP, Wimberley PD, Hall JD, Pfriemer JT, Hubbard EM, Stacy AS, et al. Teaching breast cancer screening to African American women in the Arkansas Mississippi river delta. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005;32:857–63. doi: 10.1188/05.onf.857-863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas B, Stamler LL, Lafreniere KD, Delahunt TD. Breast health educational interventions. Changes in beliefs and practices of working women. AAOHN J. 2002;50:460–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malak AT, Dicle A. Assessing the efficacy of a peer education model in teaching breast self-examination to university students. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2007;8:481–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hall CP, Hall JD, Pfriemer JT, Wimberley PD, Jones CH. Effects of a culturally sensitive education program on the breast cancer knowledge and beliefs of Hispanic women. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34:1195–202. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.1195-1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hacihasanoglu R, Gozum S. The effect of training on the knowledge levels and beliefs regarding breast self-examination on women attending a public education centre. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paskett ED, Tatum CM, D’Agostino R, Jr, Rushing J, Velez R, Michielutte R, et al. Community-based interventions to improve breast and cervical cancer screening: Results of the Forsyth County Cancer Screening (FoCaS) Project. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8:453–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ho T. Texas: Woman's University; 2006. Effects of an educational intervention on breast cancer screening and early detection in Vietnamese American women. Dissertation for doctor philosophy. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kessler TA. Increasing mammography and cervical cancer knowledge and screening behaviors with an educational program. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2012;39:61–8. doi: 10.1188/12.ONF.61-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu TY, Hsieh HF, West BT. Stages of mammography adoption in Asian American women. Health Educ Res. 2009;24:748–59. doi: 10.1093/her/cyp009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bailey EJ, Erwin DO, Belin P. Using cultural beliefs and patterns to improve mammography utilization among African-American women: The Witness Project. J Natl Med Assoc. 2000;92:136–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]