Abstract

The prevalence of obesity and diabetes mellitus type 2 is increasing rapidly around the globe. Recent insights have generated an entirely new perspective that the intestinal microbiota may play a significant role in the development of these metabolic disorders. Alterations in the intestinal microbiota composition promote systemic inflammation that is a hallmark of obesity and subsequent insulin resistance. Thus, it is important to understand the reciprocal relationship between intestinal microbiota composition and metabolic health in order to eventually prevent disease progression. In this respect, faecal transplantation studies have implicated that butyrate-producing intestinal bacteria are crucial in this process and be considered as key players in regulating diverse signalling cascades associated with human glucose and lipid metabolism.

Keywords: diabetes, host–pathogen interactions, lipopolysaccharide

OTHER ARTICLES PUBLISHED IN THIS REVIEW SERIES

Lessons from helminth infections: ES-62 highlights new interventional approaches in rheumatoid arthritis. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2014, 177: 13–23.

Microbial ‘old friends’, immunoregulation and socioeconomic status. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2014, 177: 1–12.

The intestinal microbiome in type 1 diabetes. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2014, 177: 30–7.

Helminths in the hygiene hypothesis: sooner or later? Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2014, 177: 38–46.

Introduction

The recent epidemics of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in western societies have challenged researchers to investigate the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms 1. Although genetic factors and lifestyle contribute significantly to the susceptibility of these metabolic disorders, the role of intestinal microbiota as potential partaker in the development of obesity and subsequent insulin resistance has only recently gained momentum 2. Trillions of bacteria are present in the human gastrointestinal tract containing at least 1 × 1014 bacteria made up of from 2000 to 4000 different species of (an)aerobic bacteria. Among these indigenous bacterial populations (major phyla: Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria), commensal anaerobic species also are thought to have a significant influence in host structure and function. In adults, the commensal microbial communities are relatively stable, but can undergo dynamic changes as a result of its interactions with diet, genotype/epigenetic composition and immunometabolic function. Moreover, differences in intestinal microbiota composition in the distal gastrointestinal tract appear to distinguish lean versus obese individuals, suggesting that intestinal dysbiosis contributes to the development of obesity and its consequences 3,4. In line with this, Cani et al. demonstrated that a lower abundance of Gram-positive, short chain fatty acid butyrate-producing anaerobic bacteria was associated with endotoxaemia, chronic inflammation and development of insulin resistance in mice 5. However, the question remains as to whether these changes in intestinal microbiota composition are the cause or consequence of human obesity.

In this respect, faecal bacteriotherapy or faecal transplantation has been proved to be a highly effective and successful treatment for patients with several diseases 6. The hypothesis behind the faecal bacteriotherapy rests on the concept of bacterial interference, in which pathogenic microbes are replaced by beneficial communities. We subsequently used this faecal transplantation model in a randomized control trial to test whether gut microbiota are related causally with human metabolism. Male insulin-resistant subjects with metabolic syndrome received solutions of stool from lean donors, and a significant improvement in peripheral insulin resistance was observed in conjunction with altered (small) intestinal microbiota composition 7. These include an increase in short chain fatty acid (SCFA) butyrate-producing intestinal bacteria, including Roseburia and Faecalibacterium spp. in faeces as well as small intestinal Eubacterium halli. Thus, it is tempting to speculate that intestinal bacteria are indeed causally involved in human metabolism. In this review, we aim to discuss current knowledge of intestinal (butyrate-producing) microbiota composition in obesity as well as the use of faecal transplantation using different donors to mine for beneficial intestinal bacterial strains to treat obesity and subsequent type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Development of intestinal microbiota composition

The intestinal microbiota of the newborn human was thought to be essentially sterile, but recent data suggest that modest bacterial translocation via placental circulation antenatally is likely to provide a primitive bacterial community to the meconium 8. Although the new concept of fetal intestinal colonization remains controversial, recent ongoing studies using 16S rRNA gene pyrosequencing to characterize the bacterial population in meconium of preterm infants suggest that the bacteria of maternal intestine are able to cross the placental barrier and act as the initial inoculum for the fetal gut microbiota 8,9. Nevertheless, the infant's gut is only colonized fully by maternal and environmental bacteria during birth. Whereas the vaginally delivered infant's intestinal microbial communities resemble their own mother's vaginal microbiota (dominated by Lactobacillus, Prevotella or Sneathia spp.), newborns delivered by caesarean section harbour intestinal bacterial societies similar to those found on maternal skin surface, dominated by Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium and Propionibacterium spp. 9. In this regard, it is interesting to note that mode of delivery (caesarean) is associated with increased risk of obesity later in life 10. Other than the delivery mode, gestational age at birth, diet composition and antibiotic use by the infant may have significant impacts to determine the composition of the infant's intestinal microbial communities and body mass index (BMI) 11. With respect to feeding pattern, the composition of intestinal bacteria differs substantially between breast-fed and formula-fed infants, which is thought to be due to the breast milk containing (prebiotic) oligosaccharides 12,13. The subsequent transformation of the intestinal microbiota from infant- to adult-type is triggered via bidirectional cross-talk between host and predominantly dietary and environmental factors 12,14, but remains relatively stable until the 7th decade of life 15. It is thus likely that host (immunological) responses to inhabitant commensal bacteria differ from those elicited towards pathogens that do not belong to the indigenous microbiota 16,17. The precise mechanisms of how intestinal microbes affect and protect host immune physiology, however, are yet to be revealed.

Altered intestinal microbiota in obesity and insulin resistance: low-grade endotoxaemia as unifying mechanism

There is now solid evidence that composition of the intestinal microbiota is altered in obese people on a western diet compared to lean 18,19. Moreover, dietary composition seems to be one the most important determinants of intestinal microbiota diversity driving obesity 20,21. Bacteroidetes levels increase with lower BMI, which may be due either to low-fat or low-carbohydrate diets, suggesting that the caloric intake may be correlated positively with Bacteroidetes 14. Due to differences in dietary fats in the western world in the United States versus Europe 22, it is likely that the diet-induced changes in intestinal microbiota composition could partly explain the controversy regarding, e.g. the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio in humans 4,14. Nevertheless, it is now accepted that intestinal microbiota are involved in obesity, as germ-free ob/ob mice on both normal chow and high-fat diets remain significantly leaner than conventionally raised mice, despite a significantly higher food intake 23. In line with this, metagenomic sequencing of the caecum microbiome of these ob/ob mice revealed that an enrichment of genes was involved in the breakdown of complex dietary polysaccharides 18. Similar alterations showing enriched bacterial genes involved in carbohydrate sensing and degradation have also been observed in obese humans 24. Studying intestinal microbial composition in well-phenotyped human subjects enrolled in relatively large metagenome-wide association studies (MGWAS) in both Chinese and European populations has further increased our understanding of the gut microbiota in the development of obesity and insulin resistance 25–27. Karlsson et al. detected an enrichment of L. gasseri and S. mutans (both commensal bacteria in the mouth and upper intestinal tract) to predict development of insulin resistance in their cohort of postmenopausal obese Caucasian females 26. Conversely, Qin et al.'s Chinese T2DM cohort demonstrated that Escherichia coli, a Gram-negative bacterium which is associated with development of low-grade endotoxaemia, was more abundant. Moreover, clusters of genomic sequences acted as the database signatures for specific groups of bacteria and both studies found independently that subjects with T2DM were characterized by decreased short chain fatty acid (SCFA) butyrate-producing Clostridiales bacteria (Roseburia and F. prausnitzii), and greater amounts of non-butyrate producing Clostridiales and pathogens such as C. clostridioforme, underscoring a potential unifying pathophysiological mechanism.

It has long been recognized that insulin resistance and development of type 2 diabetes are characterized by systemic and adipose inflammation 19,28. The lipopolysaccharides (LPS) produced in the intestine due to the lysis of Gram-negative bacteria triggers proinflammatory cytokines that result in insulin resistance both in mice 5 and humans 29. A more causal role was defined when germ-free mice were colonized with E. coli, as this promoted macrophage accumulation and up-regulation of proinflammatory cytokines resulting in low-grade inflammation 30. The mechanism via which LPS is translocated into the plasma might be either indirectly via indirect transport via dietary chylomicrons 31 or directly via leakage due to a decreased intestinal barrier function 5. Taken together with the MGWAS studies, these data suggest that altered (less SCFA-producing) gut microbiota composition may affect the host metabolism via impaired intestinal barrier function resulting in low-grade endotoxaemia.

Altered short chain fatty acid-producing bacteria in obesity and insulin resistance

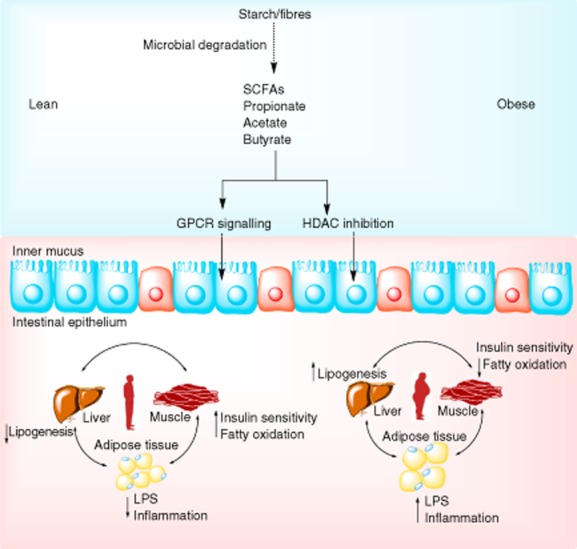

Earlier human studies had already reported that obese subjects have altered faecal SCFA levels which were linked to impaired epithelial intestinal barrier function 32. Thus, the previous reported MGWAS association of T2DM with impaired butyrate production is of interest, as oral supplementation with butyrate can reverse insulin resistance in dietary-obese mice 33 and increase energy expenditure 34, and we are currently performing such a study in human subjects with metabolic syndrome at our institution. Moreover, as germ-free mice produce almost no SCFA 35, this suggests a direct pathophysiological mechanism between intestinal microbiota composition, bacterial SCFA in the intestine and development of insulin resistance. It has long been recognized that intestinal bacteria release short chain fatty acids, peroxidases, proteases and bacteriocins to prevent pathogens from settling in the intestine 36. The main substrate available to the intestinal bacteria for this process is indigestible dietary carbohydrates, specifically dietary starches and fibres which are broken down into SCFAs (including acetate, propionate and butyrate) 32. These SCFAs may serve as an energy source for intestinal epithelium and liver, given their transport predominantly via the portal vein after intestinal absorption (see Fig. 1). Other observations suggest that the signalling properties of the altered SCFAs may be more responsible for the metabolic effects of the obesity-associated microbiota than their caloric content. For example, SCFAs signal through several G-protein (GPR)-coupled receptors, including GPR-41 and GPR-43 37. Moreover, mice lacking GPR41 (the SCFA receptor most active in intestinal epithelial cells) have lower recovery of dietary SCFAs 38, suggestive of a reciprocal mechanism between intestinal epithelial cell function, intestinal microbiota composition and their produced SCFAs. In line with this, these authors showed that the SCFA propionate was used for gluconeogenesis and lipogenesis, whereas the SCFA butyrate had a distinct effect on reduced inflammatory status via inhibition of nuclear factor (NF)-kappa-B transcription. Although it has been acknowledged that SCFAs have a direct immunomodulatory effect via improving intestinal permeability 33, another possible mechanism could be indirect by acting as a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor, affecting proliferation, differentiation and methylation of gene expression 39 (see also Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Role of gut microbiota produced short chain fatty acids on human metabolism.

Role of microbiota in bile acid homeostasis and insulin resistance

Bile acids have been highlighted as crucial metabolic integrators and signalling molecules involved in the regulation of metabolic pathways, including glucose, lipid and energy metabolism 40. Older studies from the 1970s already implicated that germ-free animals have significantly increased bile acid concentrations and flow 41. Follow-up studies showed that germ-free animals have elevated levels of conjugated bile acids throughout the intestine, with a strongly decreased faecal excretion 42. More recently, these results were confirmed in experiments with mice treated with antibiotics to eradicate endogenous intestinal microbiota. Short-term administration of antibiotics in both rodents and humans significantly altered the faecal bile acid pool with a reduced proportion of secondary bile acids compared with primary bile acids 43, as well as deterioration of insulin sensitivity 44. Moreover, our study in obese males with metabolic syndrome indicated that L. plantarum content was associated with faecal primary bile acids, whereas short chain fatty acid (butyrate)-producing bacteria (such as F. prausnitzii and E. hallii) were correlated positively with faecal secondary bile acids and inversely with faecal primary bile acids. Compelling evidence suggests that intestinal bacteria are indeed causally involved in human bile acid metabolism comes from a recently published faecal transplantation study. These authors showed in a relatively small group of subjects with C. difficile-associated diarrhoea that faecal transplantation fully restored faecal bile acid composition with a decrease in primary bile acids and increase in secondary bile acids, suggestive of normalized bile acid dehydroxylation 45, although a direct relation between glucose metabolism and normalized bile acid metabolism upon faecal transplantation was not shown in this study. Finally, in line with SCFAs, bile acids can also function as signalling molecules and bind to cellular receptors such as the bile acid synthesis-controlling nuclear receptor farnesoid X receptor (FXR) and TGR5 receptor. Both FXR and TGR5 have been implicated in the modulation of glucose homeostasis for regulation of plasma glucose levels, as TGR5 (binds secondary bile acids) promotes glucose homeostasis 46, whereas FXR (activated by primary bile acids) impairs insulin sensivitivity 47. Nevertheless, the specific (an)aerobic intestinal bacteria regulating TGR5 or FXR receptor function have not yet been identified.

Faecal transplantation in humans: overall efficacy via normalization of SCFA-producing bacteria?

Thus, the ability of the intestinal microbiota to affect host metabolism seems to be mediated by an interplay of at least four key components: dietary/nutrient intake, bile acids dehydroxylation, SCFA metablism and gut microbiota composition. As mentioned previously, we recently showed that faecal transplantation (infusing intestinal microbiota from lean donors) in humans with metabolic syndrome has beneficial effects on the recipients' microbiota composition (increase in SCFA-producing bacteria), with a concomitant improvement in insulin sensitivity 7. We also found that not all lean donors convey the same effect on insulin sensitivity, as some donors had very significant effects (so-called super-faecal donor), whereas others had no effect. Preliminary analyses have suggested that this super-donor effect is most probably conveyed by amounts of SCFA-producing intestinal bacteria in their faeces, and further research is currently ongoing at our department. Transmissibility of human obesity was demonstrated recently using faecal transplantation from weight-discordant human twin-pairs in germ-free mice. Germ-free mice that were transferred faecal stool samples from obese-twin donors had a corresponding 20% increase in adiposity compared to recipients of the lean-twin faecal microbiota 48. In a second set of experiments, using these same germ-free recipients, the authors demonstrated for the first time that obesity could be regarded as an infectious disease. For this experiment, lean-twin microbiota mouse recipients were co-housed with obese-twin microbiota mouse recipients, and non-conventionalized germ-free mice. Interestingly, intestinal microbiota from lean recipients was primarily responsible for resculpting the bacterial communities across all groups; an effect that was blunted when recipients were fed a high-fat diet, suggesting that ‘herd immunity’ can play a role in protection against obesity when individuals are raised in a lean-subject household. These findings corroborate with recent data, showing that indwelling dogs have both a skin and intestinal microbiota composition that resembles their human household members 49.

Conclusions

The intestinal microbiota is increasingly being accepted as an environmental player that affects human metabolism and may contribute to the development of obesity, insulin resistance and subsequent type 2 diabetes mellitus. Understanding the optimal intestinal microbiota composition and the key (anaerobic) bacterial species involved seems to be of pivotal importance to understanding of how to restore and maintain human health. As it is yet to be proved that intestinal bacteria play a causal role in the pathogenesis of obesity and insulin resistance, the fact that several biotech companies were founded in the last few years to mine for these diagnostic and therapeutic bacterial strains underscores the huge potential of this novel player in human metabolism 50.

Acknowledgments

A. V. H. is supported by a FP7-EU consortium grant (MyNewGut). M. N. is supported by a CVON 2012 grant (IN-CONTROL).

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Hossain P, Kawar B, El Nahas M. Obesity and diabetes in the developing world – a growing challenge. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:213–215. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tilg H, Moschen AR, Kaser A. Obesity and the microbiota. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1476–1483. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DiBaise JK, Zhang H, Crowell MD, Krajmalnik-Brown R, Decker GA, Rittmann BE. Gut microbiota and its possible relationship with obesity. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:460–469. doi: 10.4065/83.4.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duncan SH, Lobley GE, Holtrop G, et al. Human colonic microbiota associated with diet, obesity and weight loss. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32:1720–1724. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cani PD, Amar J, Iglesias MA, et al. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2007;56:1761–1772. doi: 10.2337/db06-1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smits LP, Bouter KE, de Vos WM, Borody TJ, Nieuwdorp M. Therapeutic potential of fecal microbiota transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:946–953. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vrieze A, Van Nood E, Holleman F, et al. Transfer of intestinal microbiota from lean donors increases insulin sensitivity in subjects with metabolic syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:913–916. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.06.031. http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2012.06.031 (20 June 2012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiménez E, Marín ML, Martín R, et al. Is meconium from healthy newborns actually sterile? Res Microbiol. 2008;159:187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dominguez-Bello MG, Costello EK, Contreras M, et al. Delivery mode shapes the acquisition and structure of the initial microbiota across multiple body habitats in newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:11971–11975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002601107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blustein J, Attina T, Liu M, et al. Association of caesarean delivery with child adiposity from age 6 weeks to 15 years. Int J Obes (Lond) 2013;37:900–906. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2013.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trasande L, Blustein J, Liu M, Corwin E, Cox LM, Blaser MJ. Infant antibiotic exposures and early-life body mass. Int J Obes (Lond) 2013;37:16–23. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palmer C, Bik EM, DiGiulio DB, Relman DA, Brown PO. Development of the human infant intestinal microbiota. PLOS Biol. 2007;39:e177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newburg DS. Neonatal protection by innate immune system of human milk consisting of oligosaccharides and glycans. J Anim Sci. 2009;39:26–34. doi: 10.2527/jas.2008-1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ley RE, Turnbaugh PJ, Klein S, Gordon JI. Microbial ecology: human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature. 2006;444:1022–1023. doi: 10.1038/4441022a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lozupone CA, Stombaugh JI, Gordon JI, Jansson JK, Knight R. Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature. 2012;489:220–230. doi: 10.1038/nature11550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rautava S, Walker WA. Commensal bacteria and epithelial cross talk in the developing intestine. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2007;9:385–392. doi: 10.1007/s11894-007-0047-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sudo N, Sawamura S, Tanaka K, Aiba Y, Kubo C, Koga Y. The requirement of intestinal bacterial flora for the development of an IgE production system fully susceptible to oral tolerance induction. J Immunol. 1997;159:1739–1745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, et al. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature. 2006;444:1027–1031. doi: 10.1038/nature05414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Le Chatelier E, Nielsen T, Qin J, et al. Richness of human gut microbiome correlates with metabolic markers. Nature. 2013;500:541–546. doi: 10.1038/nature12506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu GD, Chen J, Hoffmann C, et al. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science. 2011;334:105–108. doi: 10.1126/science.1208344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2013;505:559–563. doi: 10.1038/nature12820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dougherty RM, Galli C, Ferro-Luzzi A, Iacono JM. Lipid and phospholipid fatty acid composition of plasma, red blood cells, and platelets and how they are affected by dietary lipids: a study of normal subjects from Italy, Finland, and the USA. Am J Clin Nutr. 1987;45:443–455. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/45.2.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Backhed F, Ding H, Wang T, et al. The gut microbiota as an environmental factor that regulates fat storage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:15718–15723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407076101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turnbaugh PJ, Hamady M, Yatsunenko T, et al. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature. 2009;457:480–484. doi: 10.1038/nature07540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Vos WM, Nieuwdorp M. Genomics: a gut prediction. Nature. 2013;498:48–49. doi: 10.1038/nature12251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qin J, Li Y, Cai Z, et al. A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2012;490:55–60. doi: 10.1038/nature11450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karlsson FH, Tremaroli V, Nookaew I, et al. Gut metagenome in European women with normal, impaired and diabetic glucose control. Nature. 2013;498:99–103. doi: 10.1038/nature12198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osborn O, Olefsky JM. The cellular and signaling networks linking the immune system and metabolism in disease. Nat Med. 2012;18:363–374. doi: 10.1038/nm.2627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amar J, Serino M, Lange C, et al. DESIR Study Group. Involvement of tissue bacteria in the onset of diabetes in humans: evidence for a concept. Diabetologia. 2011;54:3055–3061. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2329-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caesar R, Reigstad CS, Bäckhed HK, et al. Gut-derived lipopolysaccharide augments adipose macrophage accumulation but is not essential for impaired glucose or insulin tolerance in mice. Gut. 2012;61:1701–1707. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghoshal S, Witta J, Zhong J, de Villiers W, Eckhardt E. Chylomicrons promote intestinal absorption of lipopolysaccharides. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:90–97. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800156-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwiertz A, Taras D, Schäfer K, et al. Microbiota and SCFA in lean and overweight healthy subjects. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:190–195. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Donohoe DR, Garge N, Zhang X, et al. The microbiome and butyrate regulate energy metabolism and autophagy in the mammalian colon. Cell Metab. 2011;13:517–526. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gao Z, Yin J, Zhang J, et al. Butyrate improves insulin sensitivity and increases energy expenditure in mice. Diabetes. 2009;58:1509–1517. doi: 10.2337/db08-1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maslowski KM, Vieira AT, Ng A, et al. Regulation of inflammatory responses by gut microbiota and chemoattractant receptor GPR43. Nature. 2009;461:1282–1286. doi: 10.1038/nature08530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson MT, Stinchcombe JR. An emerging synthesis between community ecology and evolutionary biology. Trends Ecol Evol. 2007;22:250–257. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tazoe H, Otomo Y, Kaji I, Tanaka R, Karaki SI, Kuwahara A. Roles of short chain fatty acids receptors, GPR41 and GPR43 on colonic functions. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008;59(Suppl. 2):251–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Samuel BS, Shaito A, Motoike T, et al. Effects of the gut microbiota on host adiposity are modulated by the short chain fatty-acid binding G protein-coupled receptor, Gpr41. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:16767–16772. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808567105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davie JR. Inhibition of histone deacetylase activity by butyrate. J Nutr. 2003;133(Suppl. 7):2485S–2493. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.7.2485S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomas C, Pellicciari R, Pruzanski M, Auwerx J, Schoonjans K. Targeting bile-acid signalling for metabolic diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:678–693. doi: 10.1038/nrd2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wostmann BS. Intestinal bile acids and cholesterol absorption in the germfree rat. J Nutr. 1973;103:982–990. doi: 10.1093/jn/103.7.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Madsen D, Beaver M, Chang L, Bruckner-Kardoss E, Wostmann B. Analysis of bile acids in conventional and germfree rats. J Lipid Res. 1976;17:107–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miyata M, Takamatsu Y, Kuribayashi H, Yamazoe Y. Administration of ampicillin elevates hepatic primary bile acid synthesis through suppression of ileal fibroblast growth factor 15 expression. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;31:1079–1085. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.160093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vrieze A, Out C, Fuentes S, et al. Vancomycin decreases insulin sensitivity and is associated with alterations in intestinal microbiota and bile acid composition in obese subjects with metabolic syndrome. J Hepatol. 2013;60:824–831. P. ii: S0168-8278(13)00837-4. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weingarden AR, Chen C, Bobr A, et al. Microbiota transplantation restores normal fecal bile acid composition in recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2013;306:G310–319. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00282.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thomas C, Gioiello A, Noriega L, et al. TGR5-mediated bile acid sensing controls glucose homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2009;10:167–177. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prawitt J, Abdelkarim M, Stroeve JH, et al. Farnesoid X receptor deficiency improves glucose homeostasis in mouse models of obesity. Diabetes. 2011;60:1861–1871. doi: 10.2337/db11-0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ridaura VK, Faith JJ, Rey FE, et al. Gut microbiota from twins discordant for obesity modulate metabolism in mice. Science. 2013;341:1241214. doi: 10.1126/science.1241214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Song SJ, Lauber C, Costello EK, et al. Cohabiting family members share microbiota with one another and with their dogs. eLife. 2013;2:e00458. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Olle B. Medicines from microbiota. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:309–315. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]