Abstract

Ro52 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase with a prominent regulatory role in inflammation. The protein is a common target of circulating autoantibodies in rheumatic autoimmune diseases, particularly Sjögren's syndrome (SS). In this study we aimed to investigate the expression of the SS target autoantigen Ro52 in salivary glands of patients with primary Sjögren's syndrome (pSS). Ro52 expression was assessed by immunohistochemical staining of paraffin-embedded and frozen salivary gland biopsies from 28 pSS patients and 19 non-pSS controls from Swedish and Norwegian registries, using anti-human Ro52 monoclonal antibodies. The degree and pattern of staining and inflammation was then evaluated. Furthermore, secreted Ro52 protein was measured in saliva and serum samples from the same individuals through a catch-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Ro52 was highly expressed in all the focal infiltrates in pSS patients. Interestingly, a significantly higher degree of Ro52 expression in ductal epithelium was observed in the patients compared to the non-pSS controls (P < 0·03). Moreover, the degree of ductal epithelial expression of Ro52 correlated with the level of inflammation (Spearman's r = 0·48, P < 0·0120). However, no secreted Ro52 protein could be detected in serum and saliva samples of these subjects. Ro52 expression in ductal epithelium coincides with degree of inflammation and is up-regulated in pSS patients. High expression of Ro52 might result in the breakage of tolerance and generation of Ro52 autoantibodies in genetically susceptible individuals. We conclude that the up-regulation of Ro52 in ductal epithelium might be a triggering factor for disease progression in SS.

Keywords: autoimmunity, inflammation, Ro52, salivary glands, Sjögren's syndrome

Introduction

Autoantibodies against Ro52 are often detected in patients diagnosed with autoimmune diseases such as primary Sjögren's syndrome (pSS), but can also be present in healthy individuals 1–3. Interestingly, these autoantibodies have been found to be present long before symptom onset in both pSS and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) 4,5. The target for these Ro52-specific autoantibodies is a 52-kDa intracellular protein that was shown to be a RING-dependent E3 ubiquitin ligase 6–8. It acts in the process of ubiquitination, a post-translational modification that marks proteins for degradation, trafficking and activation, thereby allowing eukaryotic cells to control important biological processes 9. Through the ubiquitination of interferon regulatory factors (IRFs), particularly IRF 3, 5, 7 and 8, Ro52 has been shown to have a central regulatory role in inflammation. It modifies the transcriptional activity of these IRFs resulting in increased proinflammatory cytokine production, including interleukin (IL)-12/IL-23p40, tumour necrosis factor (TNF), IL-6 and type I interferon (IFN) 6,7,10–16. Interestingly, Sjögren's syndrome (SS) patients seem to have autoantibody specificities against several different epitopes of the Ro52 protein, including its RING, B-box and CC domains 17–19.

In addition to high serum titres of autoantibodies 20–23, a fundamental diagnostic feature of SS is chronic inflammation manifested by mononuclear cell infiltration of exocrine glands, particularly lachrymal and salivary glands (SG) 24–27. A process starts that eventually results in the replacement of the glandular epithelium by infiltrating mononuclear cells, leading to dysfunction and later destruction of the glands 28,29. B cells are known to make up 20% of the infiltrating cell populations in exocrine glands 30,31, and can result in the formation of structures similar to those of organized secondary lymphoid tissue in some instances 32. Indeed, 25% of pSS patients demonstrate ectopic germinal centres (GC) in their exocrine glands 33–35.

To date, primarily Ro52 autoantibody-producing cells have been explored in SG of pSS patients 23,36,37. Previous reports have shown that the Ro52 protein is expressed mainly in cells of haematopoietic origin. Although the Ro52 mRNA expression has been described previously 38, a detailed characterization of the expression pattern in the target organ remains to be defined. For these reasons we aimed to investigate the expression of the SS target autoantigen Ro52 in SG of pSS patients. By employing previously generated anti-human monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that target different domains of the Ro52 protein 14, immunohistochemical staining of both frozen and paraffin-embedded tissue of lower labial SG biopsies from both Swedish and Norwegian patient cohorts was performed and the Ro52 expression pattern was analysed. In addition to this, a capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was established to measure levels of secreted Ro52 protein in serum and saliva samples from the same subjects. Here we show that Ro52 was highly expressed in all the focal infiltrates of SG tissue. Interestingly, ductal epithelial expression of Ro52 correlated with the degree of inflammation in the SG biopsies. However, very little to no secreted Ro52 protein could be detected in saliva and serum samples of these individuals.

Materials and methods

Study cohort

Labial minor salivary glands from 28 patients fulfilling the American–European consensus group criteria (AECC) for pSS 26 were included and diagnosed at the Department of Medicine at Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden and the Department of Otolaryngology/Head and Neck Surgery at Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway between 1992 and 2013. Twenty SG biopsies from subjects evaluated for SS at the same period and departments, but not fulfilling the criteria (sicca controls), served as non-pSS tissue controls. Serum and unstimulated saliva were sampled at the time of biopsy and stored at −70°C in aliquots.

Clinical data were obtained from medical records, including focus score, anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA), anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB, and extra-glandular manifestations, shown in Table 1. All studied subjects gave informed consent, and the Committee of Ethics at the Karolinska Institute and University of Bergen approved the study.

Table 1.

Medical and experimental characteristics of primary Sjögren's syndrome (pSS) patients included in the study

| Patient no. | Age (years) | Gender | ANA | SSA | SSB | Focus† score | Ratio‡ index | Dry mouth | Extraglandular manifestations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 24 | F | + | + | + | 3 | 0·119 | + | + |

| P2 | 24 | F | + | + | + | 4 | 0·106 | + | + |

| P3 | 50 | F | + | + | + | 0 | 0·011 | + | − |

| P4 | 58 | F | − | − | + | 0 | 0·084 | + | + |

| P5 | 57 | F | DU | − | − | 1 | 0·000 | + | − |

| P6 | 55 | F | − | + | + | 0 | 0·000 | + | − |

| P7 | 19 | F | + | + | + | 1 | 0·047 | − | − |

| P8 | 59 | F | + | + | + | DU | 0·164 | + | − |

| P9 | 67 | F | + | + | + | 3 | 0·000 | + | − |

| P10 | 33 | F | + | + | + | 1 | 0·000 | + | + |

| P11 | 62 | F | + | + | + | 10 | 0·101 | + | − |

| P12 | 61 | F | − | + | + | 1 | 0·074 | + | + |

| P13 | 33 | F | + | + | + | 12 | 0·053 | + | + |

| P14 | 26 | F | + | + | + | 1 | 0·050 | + | + |

| P15 | 48 | F | − | + | − | 0 | 0·110 | + | + |

| P16 | 74 | F | − | + | − | 0 | 0·156 | + | + |

| P17 | 36 | F | + | + | + | 2 | 0·222 | + | − |

| P18 | 56 | F | + | − | − | 4 | DU | + | − |

| P19 | 40 | F | − | − | − | 2 | 0·034 | DU | + |

| P20 | 63 | F | + | + | + | 3 | 0·086 | + | − |

| P21 | 51 | F | + | + | − | 0 | 0·014 | − | + |

| P22 | 62 | F | + | − | − | 1 | 0·028 | − | + |

| P23 | 61 | F | + | + | − | 1 | 0·089 | + | + |

| P24 | 59 | F | + | + | − | 0 | 0·013 | + | − |

| P25 | 20 | F | + | + | + | 3 | 0·239 | DU | + |

| P26 | 39 | F | + | − | − | 0 | 0·022 | + | + |

| P27 | 57 | F | + | + | − | 2 | 0·037 | + | − |

| P28 | 51 | F | − | − | − | 1 | 0·022 | + | − |

Focus score: the number of inflammatory focal infiltrates of more than 50 mononuclear cells per 4 mm2 glandular tissue area assessed at diagnosis.

Ratio index: represents the sum of the area of all focal infiltrates/total gland area in sections used in this investigation. ANA = anti-nuclear antibodies; DU = data unavailable; GC = germinal centre; F = female; M = male.

Immunohistochemistry

Frozen biopsies were sectioned (7 μm) in a cryostat. The sections were placed on chrome gelatin-coated slides and air-dried for 30 min before fixation in ice-cold 50% acetone for 30 s, followed by 3 min in 100% acetone, and thereafter air-dried. Sections of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded minor SG biopsies were sectioned using a microtome (4–6 μM thick). The sections were placed on SuperFrost® Plus microscope slides and incubated overnight at 56°C. This was followed by deparaffinization in xylene, and rehydration through a graded ethanol series (100, 96, 70%) and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The sections were then subjected to heat-induced epitope retrieval (HIER) with citrate buffer (pH 6·0) at 98°C for 30 min, thereafter allowing the slides to cool, and washing in water for 5 min. From here onwards, the same immunohistochemical staining protocol was used for both paraffin-embedded and frozen tissue sections.

In brief, endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked using endogenous enzyme block (K4011; Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA) for 10 min. Primary antibody (Ro52 mouse monoclonal 7·8C7) 39 or corresponding amount of isotype control (mouse IgG1; DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark) 14 was added to the sections and incubated for 60 min in a humidified chamber. A concentration of 1 μg/ml was applied to paraffin sections and 3 μg/ml to frozen sections in PBS containing 0·1% saponin and 2% horse serum. This was followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse Envision secondary antibody (K4011; Dako) for 30 min. Thereafter, sections were incubated for 10 min with diaminobenzidine (DAB) (K4011; Dako). All incubations were performed at room temperature (RT), and PBS containing 0·1% saponin was used as washing buffer (pH 7·6) between every step for 10 min. Finally, the sections were counterstained with Mayer's haematoxylin and mounted under coverslips using Mountex (HistoLab, Gothenburg, Sweden).

Evaluation of staining

The minor SG sections were analysed by three investigators. Both mononuclear cells in focal infiltrates and those located interstitially, i.e. in close proximity to the acinar or ductal epithelium, were analysed. Furthermore, the SG sections were scored blindly by two investigators (L. A., M. W. H) for the presence of focal infiltrates and whether or not these focal infiltrates were positively stained for Ro52 protein, and Ro52 staining of ductal epithelium was also assessed. Depending on the degree of positivity, either number 0, 1 or 2 was assigned for each category during assessment, where 0 was considered negative, 1 was regarded positive and 2 represented strongly positive. Also, given that focus scoring is a semi-quantitative method that only accounts for focal infiltrates comprised of > 50 mononuclear cells/4 mm2 of tissue, we decided to apply morphometry and score the sections by calculating the ratio-index in each gland. The ratio-index is defined as the total inflammatory area of focal infiltrates in the section divided by the total glandular tissue area 40. Thus, this provided more information on inflammation severity and pattern for each patient in addition to the focus score.

Capture ELISA

High-binding 96-well plates (Nunc, Odenno, Denmark) were coated overnight with 1 μg/well with Ro52 mouse monoclonal 7·1F2 antibody 14, diluted in carbonate buffer (pH 9·6) and incubated overnight. Plates were blocked with 5% fat-free milk diluted in carbonate buffer (pH 9·6) for 45 min, prior to incubation with patient sera or saliva at 1 : 50 in PBS containing 0·05% Tween and 0·5% fat-free milk (PBST/milk) for 60 min. Purified full-length recombinant Ro52 protein expressed from the pMAL-vector (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA, USA) and wild-type vector-encoded maltose-binding protein were used as a positive and negative control, respectively, at a concentration of 1 μg per well. All samples were run in duplicate. This was followed by incubation with biotinylated Ro52 mouse monoclonal 7·8C7 antibody 14, diluted at 1 μg per well in PBST/milk for 60 min. Alkaline phosphatase (ALP)-conjugated streptavidin (D0396; Dako A/S, Glostrup, Denmark) was used for detecting bound antibodies diluted at 1:2000 in PBST/milk, with phosphatase substrate (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) dissolved in diethanolamine buffer (pH 9·6), and the absorbance was measured at 405 nm. The ELISA plate was washed using 0·09% NaCl in dH2O w/20% Tween between each step. All steps were performed at RT, except coating, which was performed at 4°C.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the Mann–Whitney U-test. A P-value ≤ 0·05 was considered significant. In addition, Spearman's non-parametric correlation test was used to examine the association between the different parameters.

Results

Expression of Ro52/TRIM21 in salivary gland tissue examined by immunohistochemistry

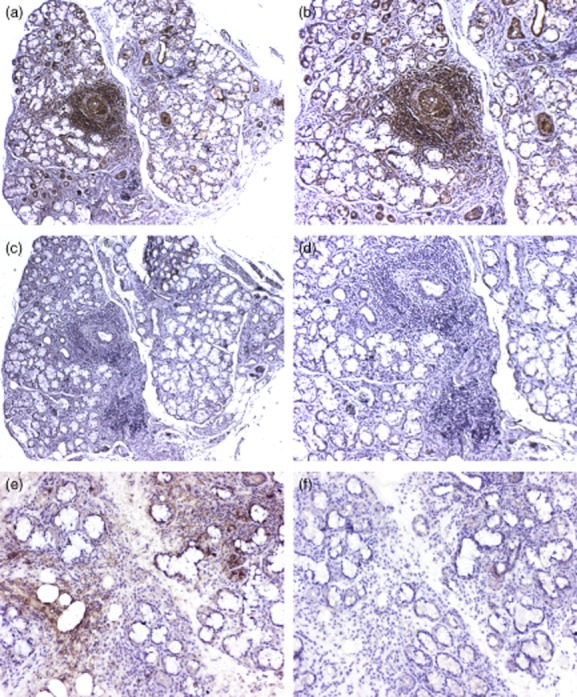

Ro52 was highly expressed in all focal infiltrates in pSS patients, including both B and T cell zones, while an isotype-matched control antibody yielded no staining (Fig. 1a–d). Preincubation of the Ro52 mAb with recombinant Ro52 protein abolished the staining in SG biopsies, demonstrating the specificity for Ro52 (Fig. 1e,f).

Fig. 1.

Ro52 expression in focal infiltrates of primary Sjögren's syndrome (pSS) patients. Ro52 is highly expressed in all the focal infiltrates in pSS patients (a,b). Mouse immunoglobulin (Ig)G1 was used as isotype control, with no staining detected (c,d). Additionally, preincubation of the Ro52 monoclonal antibody (mAb) with recombinant Ro52 protein abolishes the detection of Ro52 in SG biopsies (f). This demonstrates that staining is specific for Ro52 (e,f).

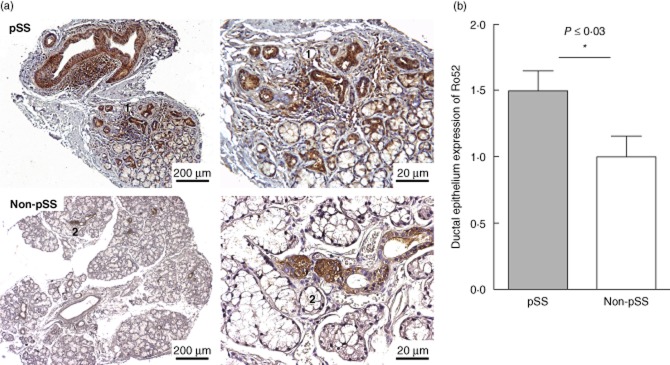

Moreover, Ro52 expression was observed in the ductal epithelium of SG tissue in both the patients and the controls (Fig. 2a). However, Ro52 was significantly more expressed in pSS patient ductal epithelium compared to non-pSS controls as assessed by a semi-quantitative score (P ≤ 0·03) (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Ro52 expression in ductal epithelium. Ro52 is also expressed in the ductal epithelium of salivary gland (SG) tissue in both the patients and the sicca controls. However, after scoring the sections, we observed a significant up-regulation of Ro52 in ductal epithelium of the primary Sjögren's syndrome (pSS) patients compared to the non-pSS controls (P ≤ 0·03). The same structures in the left and right sections are indicated with numbers 1 and 2.

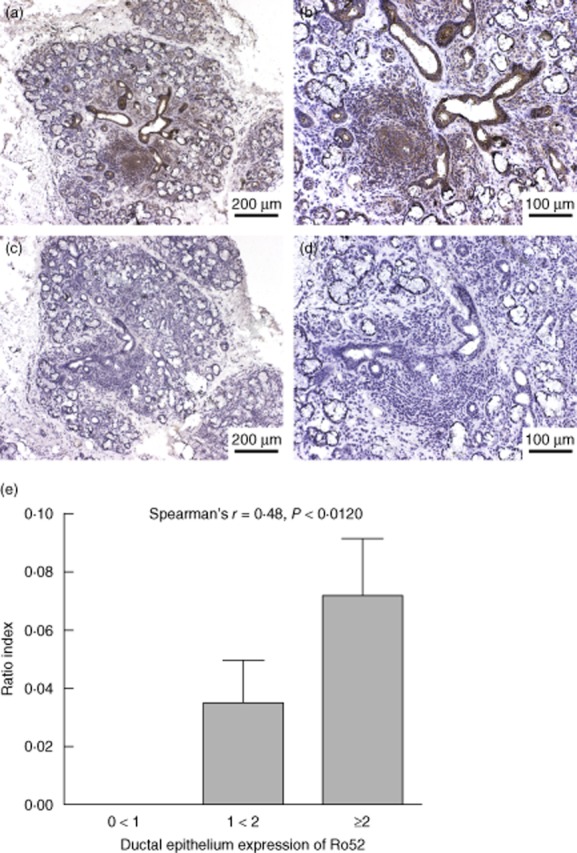

Ro52 expression correlates with level of inflammation

Further analysis of the expression pattern of Ro52 in SG biopsies revealed that the degree of ductal epithelium expression of Ro52 correlated with the level of inflammation, where pSS patients with greater mononuclear cell infiltration exhibited a higher Ro52 expression in their ductal epithelium (Spearman's r = 0·48, P < 0·0120) (Fig. 3a,b).

Fig. 3.

High ductal epithelium expression of Ro52 correlates with level of inflammation. Primary Sjögren's syndrome (pSS) patients with more evident mononuclear cell infiltration and a consequent up-regulation of Ro52 in their infiltrates also exhibited a higher Ro52 expression in their ductal epithelium; Spearman's r = 0·48, P < 0·0120 (a,b,e). Mouse immunoglobulin (Ig)G1 was used as isotype control with no staining detected (c,d).

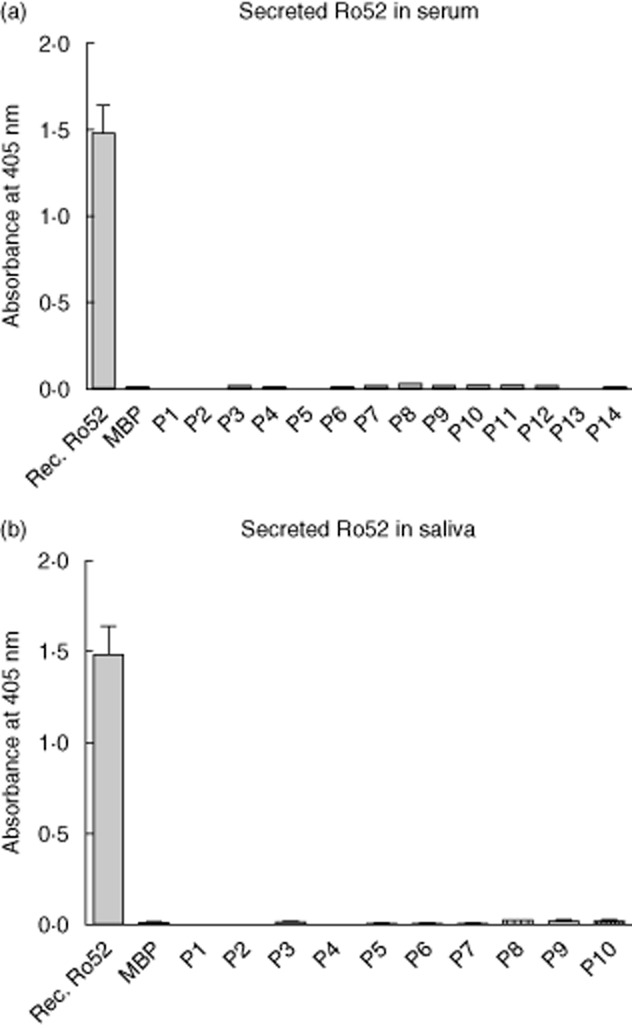

No secreted Ro52 protein in serum or saliva

Having observed ductal epithelial expression of Ro52 in SG tissue, we were interested to determine whether Ro52 protein could be secreted to saliva or serum similarly to other inflammation-related molecules such as HMGB1 29. By using the previously generated 7·1F2 Ro52 mAb 14 and biotinylated 7·8C7 Ro52 mAb a capture ELISA was established, in which saliva and serum samples from both our patient cohort and non-pSS sicca controls were analysed. Incubation with purified full-length recombinant Ro52 protein or with maltose-binding protein was used as a positive and negative control, respectively. No or minimal amount of secreted Ro52 protein could be detected in saliva and serum samples of both pSS patients and non-pSS controls (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Secreted Ro52 protein in serum and saliva of primary Sjögren's syndrome (pSS) and non-pSS subjects. Very little or no Ro52 protein could be detected in serum and saliva samples of both pSS patients and non-pSS controls, indicating that Ro52 is not secreted as part of the inflammatory process. Incubation with recombinant Ro52 protein is used as a positive control, and maltose binding protein (MBP) as a negative control.

Discussion

Anti-Ro52 autoantibodies are a characteristic feature of SS. However, the expression of this autoantigen in the autoimmune target organs is not well known. In this study, we used a generated anti-Ro52 mAb 3 that targets the coiled-coil region of the protein for assessment of Ro52 expression in SG of pSS patients and non-pSS sicca controls. Immunohistochemical staining of both paraffin-embedded and frozen tissue sections was carried out, and the sections were then scored in order to evaluate the degree and pattern of staining and inflammation.

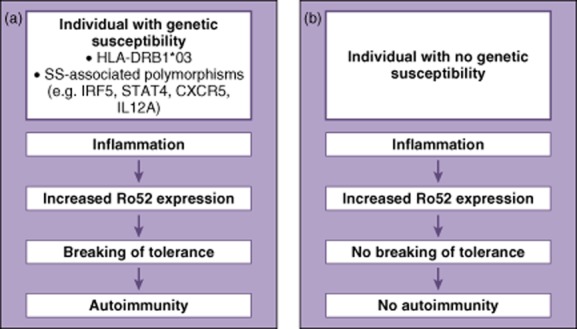

We found that Ro52 was up-regulated in all the focal infiltrates in pSS patients, and also observed Ro52 in the ductal epithelium of SG tissue in both the patients and the controls. Interestingly, pSS patients with more evident mononuclear cell infiltration and a consequent up-regulation of Ro52 in their infiltrates also exhibited a significantly higher Ro52 expression in their ductal epithelium compared to the non-pSS controls. Hence, the degree of ductal epithelium expression of Ro52 correlated with the severity of inflammation. Given that Ro52 is known to be up-regulated by several proinflammatory stimuli 3,8,9, and specifically that type 1 IFN 41 is known to be produced in the glands in pSS, our findings further demonstrate how Ro52 expression is induced by inflammation. A similar pattern was evident in our previous study, where the expression of Ro52 in skin lesions of lupus patients coincided with the level of inflammation in the tissue, and was also over-expressed in patients compared to controls 39. Interestingly, autoimmune responses against the Ro52-autoantigen have also been observed in other autoimmune diseases, such as polymyositis and scleroderma, signifying how anti-Ro52 autoantibody production is regarded as a general feature of systemic autoimmunity 19,42. Furthermore, this increased chronic expression of Ro52 in an autoimmune setting may lead to peripheral breakage of tolerance, especially in the SG, a target organ of SS where ectopic GC formation is known to occur 34. None the less, the development of Ro52 autoantibodies is not merely dependent upon high Ro52 protein expression levels. Other factors that influence the generation of Ro52 antibodies have been identified previously, pinpointing how human leucocyte antigen (HLA) is associated with Ro52-specific autoantibody production 13,18,43. Hence, the genetic background of the individual may thus determine whether Ro52 antibodies indeed develop in response to high Ro52 protein expression during inflammation 19. A schematic illustration of how immune tolerance may be broken to Ro52 in patients with pSS is presented in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

A schematic illustration of how Ro52 over-expression may lead to the breakage of immune tolerance in genetically susceptible individuals and the development of autoimmunity. Increased Ro52 expression occurs during inflammation, and in genetically susceptible individuals carrying e.g. human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-DRB1*03, and/or one or more of several SS-associated polymorphisms, this may result in the breakage of immune tolerance and autoimmunity (a). Individuals lacking the genetic component do not have a breakage of tolerance as a result of increased Ro52 expression and therefore no autoimmune responses are mounted (b).

Over-expression of Ro52 has been associated with decreased cell proliferation and apoptosis induction 6, which could explain why excessive mononuclear cell infiltration in SG tissue leads eventually to tissue degeneration and impairment in saliva production. This is also evident in our patient cohort, where 92% of the subjects suffered from the common symptom of dry mouth (Table 1). Having further observed ductal epithelial expression of Ro52 in SG tissue, we wished to investigate whether Ro52 protein could be secreted to saliva or serum, being similar to other inflammation-related molecules such as HMGB1 29. A capture ELISA was established in which saliva and serum samples from both our patient cohort and non-pSS sicca controls were analysed. The analysis demonstrated that very little to no secreted Ro52 protein could be detected in saliva and serum samples of both pSS patients and non-pSS controls, suggesting that Ro52 is not secreted as part of the inflammatory process.

In conclusion, Ro52 expression in ductal epithelium coincides with the degree of inflammation and is up-regulated in pSS patients, which suggests its biological role in inflammation of SG tissue in particular, possibly leading to tissue degeneration in SG as the disease advances and following impairment in saliva production. This chronic expression of Ro52 might result in the breakage of tolerance and generation of Ro52 autoantibodies in genetically susceptible individuals. We propose that the up-regulation of Ro52 in ductal epithelium might be a triggering factor for disease progression in SS through several pathways.

Acknowledgments

We appreciatively acknowledge Professor Johan G. Brun from the Department of Rheumatology, Haukeland University Hospital for providing the clinical information on subjects included in the study, Professor Anne Christine Johannessen for the routine histological assessment of the biopsies, Gunnvor Øijordsbakken and Edith Fick, all Gade Laboratorium for Pathology, Department of Clinical Medicine, for sectioning of the biopsies, Pia Maria Hillstedt for sectioning of the biopsies and Amina Ossoinak and Marianne Engström, all Department of Medicine, Karolinska Institutet, for excellent technical assistance. This study was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council, the Heart–Lung Foundation, the Stockholm County Council, Karolinska Institutet, the Swedish Rheumatism Association, the King Gustaf the V:th 80-year Foundation, the Torsten and Ragnar Söderberg Foundation, the Brogelmann Foundation and the Strategic Research Program at Helse Bergen.

Disclosures

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Blange I, Ringertz NR, Pettersson I. Identification of antigenic regions of the human 52kD Ro/SS-A protein recognized by patient sera. J Autoimmun. 1994;7:263–274. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1994.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garberg H, Jonsson R, Brokstad KA. The serological pattern of autoantibodies to the Ro52, Ro60, and La48 autoantigens in primary Sjogren's syndrome patients and healthy controls. Scand J Rheumatol. 2005;34:49–55. doi: 10.1080/03009740510017940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Popovic K, Wahren-Herlenius M, Nyberg F. Clinical follow-up of 102 anti-Ro/SSA-positive patients with dermatological manifestations. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:370–375. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jonsson R, Theander E, Sjostrom B, Brokstad K, Henriksson G. Autoantibodies present before symptom onset in primary Sjogren syndrome. JAMA. 2013;310:1854–1855. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eriksson C, Kokkonen H, Johansson M, Hallmans G, Wadell G, Rantapaa-Dahlqvist S. Autoantibodies predate the onset of systemic lupus erythematosus in northern Sweden. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:R30. doi: 10.1186/ar3258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Espinosa A, Zhou W, Ek M, et al. The Sjogren's syndrome-associated autoantigen Ro52 is an E3 ligase that regulates proliferation and cell death. J Immunol. 2006;176:6277–6285. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.6277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reymond A, Meroni G, Fantozzi A, et al. The tripartite motif family identifies cell compartments. EMBO J. 2001;20:2140–2151. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.9.2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wada K, Kamitani T. Autoantigen Ro52 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;339:415–421. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hershko A, Heller H, Elias S, Ciechanover A. Components of ubiquitin–protein ligase system. Resolution, affinity purification, and role in protein breakdown. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:8206–8214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jonsson MV, Szodoray P, Jellestad S, Jonsson R, Skarstein K. Association between circulating levels of the novel TNF family members APRIL and BAFF and lymphoid organization in primary Sjogren's syndrome. J Clin Immunol. 2005;25:189–201. doi: 10.1007/s10875-005-4091-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kong HJ, Anderson DE, Lee CH, et al. Cutting edge: autoantigen Ro52 is an interferon inducible E3 ligase that ubiquitinates IRF-8 and enhances cytokine expression in macrophages. J Immunol. 2007;179:26–30. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higgs R, Ni Gabhann J, Ben Larbi N, Breen EP, Fitzgerald KA, Jefferies CA. The E3 ubiquitin ligase Ro52 negatively regulates IFN-beta production post-pathogen recognition by polyubiquitin-mediated degradation of IRF3. J Immunol. 2008;181:1780–1786. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.3.1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Espinosa A, Dardalhon V, Brauner S, et al. Loss of the lupus autoantigen Ro52/Trim21 induces tissue inflammation and systemic autoimmunity by disregulating the IL-23-Th17 pathway. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1661–1671. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strandberg L, Ambrosi A, Espinosa A, et al. Interferon-alpha induces up-regulation and nuclear translocation of the Ro52 autoantigen as detected by a panel of novel Ro52-specific monoclonal antibodies. J Clin Immunol. 2008;28:220–231. doi: 10.1007/s10875-007-9157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manz RA, Hauser AE, Hiepe F, Radbruch A. Maintenance of serum antibody levels. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:367–386. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshimi R, Chang TH, Wang H, Atsumi T, Morse HC, III, Ozato K. Gene disruption study reveals a nonredundant role for TRIM21/Ro52 in NF-kappaB-dependent cytokine expression in fibroblasts. J Immunol. 2009;182:7527–7538. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bozic B, Pruijn GJ, Rozman B, van Venrooij WJ. Sera from patients with rheumatic diseases recognize different epitope regions on the 52-kD Ro/SS-A protein. Clin Exp Immunol. 1993;94:227–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1993.tb03436.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ottosson L, Hennig J, Espinosa A, Brauner S, Wahren-Herlenius M, Sunnerhagen M. Structural, functional and immunologic characterization of folded subdomains in the Ro52 protein targeted in Sjogren's syndrome. Mol Immunol. 2006;43:588–598. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arentz G, Thurgood LA, Lindop R, Chataway TK, Gordon TP. Secreted human Ro52 autoantibody proteomes express a restricted set of public clonotypes. J Autoimmun. 2012;39:466–470. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franceschini F, Cavazzana I. Anti-Ro/SSA and La/SSB antibodies. Autoimmunity. 2005;38:55–63. doi: 10.1080/08916930400022954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Volchenkov R, Jonsson R, Appel S. Anti-Ro and anti-La autoantibody profiling in Norwegian patients with primary Sjogren's syndrome using luciferase immunoprecipitation systems (LIPS) Scand J Rheumatol. 2012;41:314–315. doi: 10.3109/03009742.2012.670863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gordon TP, Bolstad AI, Rischmueller M, Jonsson R, Waterman SA. Autoantibodies in primary Sjogren's syndrome: new insights into mechanisms of autoantibody diversification and disease pathogenesis. Autoimmunity. 2001;34:123–132. doi: 10.3109/08916930109001960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aqrawi LA, Skarstein K, Oijordsbakken G, Brokstad KA. Ro52- and Ro60-specific B cell pattern in the salivary glands of patients with primary Sjogren's syndrome. Clin Exp Immunol. 2013;172:228–237. doi: 10.1111/cei.12058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jonsson R, Bolstad AI, Brokstad KA, Brun JG. Sjogren's syndrome – a plethora of clinical and immunological phenotypes with a complex genetic background. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2007;1108:433–447. doi: 10.1196/annals.1422.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kassan SS, Moutsopoulos HM. Clinical manifestations and early diagnosis of Sjogren syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1275–1284. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.12.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vitali C, Bombardieri S, Jonsson R, et al. Classification criteria for Sjogren's syndrome: a revised version of the European criteria proposed by the American-European Consensus Group. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:554–558. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.6.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scardina GA, Spano G, Carini F, et al. Diagnostic evaluation of serial sections of labial salivary gland biopsies in Sjogren's syndrome. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2007;12:E565–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jonsson R, Vogelsang P, Volchenkov R, Espinosa A, Wahren-Herlenius M, Appel S. The complexity of Sjogren's syndrome: novel aspects on pathogenesis. Immunol Lett. 2011;141:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pullerits R, Jonsson IM, Verdrengh M, et al. High mobility group box chromosomal protein 1, a DNA binding cytokine, induces arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:1693–1700. doi: 10.1002/art.11028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hansen A, Lipsky PE, Dorner T. B cells in Sjogren's syndrome: indications for disturbed selection and differentiation in ectopic lymphoid tissue. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9:218–229. doi: 10.1186/ar2210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jonsson R, Nginamau E, Szyszko E, Brokstad KA. Role of B cells in Sjogren's syndrome – from benign lymphoproliferation to overt malignancy. Front Biosci. 2007;12:2159–2170. doi: 10.2741/2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jonsson MV, Skarstein K, Jonsson R, Brun JG. Serological implications of germinal center-like structures in primary Sjogren's syndrome. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:2044–2049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamel KM, Liarski VM, Clark MR. Germinal center B-cells. Autoimmunity. 2012;45:333–347. doi: 10.3109/08916934.2012.665524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salomonsson S, Jonsson MV, Skarstein K, et al. Cellular basis of ectopic germinal center formation and autoantibody production in the target organ of patients with Sjogren's syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:3187–3201. doi: 10.1002/art.11311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jung J, Choe J, Li L, Choi YS. Regulation of CD27 expression in the course of germinal center B cell differentiation: the pivotal role of IL-10. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:2437–2443. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(2000)30:8<2437::AID-IMMU2437>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Halse A, Harley JB, Kroneld U, Jonsson R. Ro/SS-A-reactive B lymphocytes in salivary glands and peripheral blood of patients with Sjogren's syndrome. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;115:203–207. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00778.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salomonsson S, Wahren-Herlenius M. Local production of Ro/SSA and La/SSB autoantibodies in the target organ coincides with high levels of circulating antibodies in sera of patients with Sjogren's syndrome. Scand J Rheumatol. 2003;32:79–82. doi: 10.1080/03009740310000076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bolstad AI, Eiken HG, Rosenlund B, Alarcon-Riquelme ME, Jonsson R. Increased salivary gland tissue expression of Fas, Fas ligand, cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4, and programmed cell death 1 in primary Sjogren's syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:174–185. doi: 10.1002/art.10734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oke V, Vassilaki I, Espinosa A, et al. High Ro52 expression in spontaneous and UV-induced cutaneous inflammation. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2000–2010. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Manz RA, Thiel A, Radbruch A. Lifetime of plasma cells in the bone marrow. Nature. 1997;388:133–134. doi: 10.1038/40540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sjostrand M, Ambrosi A, Brauner S, et al. Expression of the immune regulator tripartite-motif 21 is controlled by IFN regulatory factors. J Immunol. 2013;191:3753–3763. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roberts-Thomson PJ, Nikoloutsopoulos T, Cox S, Walker JG, Gordon TP. Antinuclear antibody testing in a regional immunopathology laboratory. Immunol Cell Biol. 2003;81:409–412. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2003.01181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jonsson MV, Delaleu N, Brokstad KA, Berggreen E, Skarstein K. Impaired salivary gland function in NOD mice: association with changes in cytokine profile but not with histopathologic changes in the salivary gland. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2300–2305. doi: 10.1002/art.21945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]