Abstract

Context

Scotland is the first country in the world to pass legislation introducing a minimum unit price (MUP) for alcohol in an attempt to reduce consumption and associated harms by increasing the price of the cheapest alcohol. We investigated the competing ways in which policy stakeholders presented the debate. We then established whether a change in framing helped explain the policy's emergence.

Methods

We conducted a detailed policy case study through analysis of evidence submitted to the Scottish parliament, and in-depth, one-to-one interviews (n = 36) with politicians, civil servants, advocates, researchers, and industry representatives.

Findings

Public- and voluntary-sector stakeholders tended to support MUP, while industry representatives were more divided. Two markedly different ways of presenting alcohol as a policy problem were evident. Critics of MUP (all of whom were related to industry) emphasized social disorder issues, particularly among young people, and hence argued for targeted approaches. In contrast, advocates for MUP (with the exception of those in industry) focused on alcohol as a health issue arising from overconsumption at a population level, thus suggesting that population-based interventions were necessary. Industry stakeholders favoring MUP adopted a hybrid framing, maintaining several aspects of the critical framing. Our interview data showed that public health advocates worked hard to redefine the policy issue by deliberately presenting a consistent alternative framing.

Conclusions

Framing alcohol policy as a broad, multisectoral, public health issue that requires a whole-population approach has been crucial to enabling policymakers to seriously consider MUP, and public health advocates intentionally presented alcohol policy in this way. This reframing helped prioritize public health considerations in the policy debate and represents a deliberate strategy for consideration by those advocating for policy change around the world and in other public health areas.

Keywords: alcohol, policy, minimum unit pricing, public health

In May 2012, Scotland became the first country in the world to pass legislation introducing a minimum unit price for alcohol.1 Although Scotland has yet to implement the measure, following legal challenges by alcohol producers,2,3 its policy potential has attracted international interest.4–6 Public health policy interventions (such as minimum unit pricing, smoke-free legislation for public places, and taxes on sugary drinks) have been identified as having considerable potential to improve the population's health and address health inequalities.7,8 In addition, from a health sector perspective, many of these policy interventions impose relatively few financial costs while yielding considerable benefits.9 At present, however, our understanding of how public health interventions are adopted as policy is inadequate and largely derived from the field of tobacco control.10–14

Public health experts have repeatedly expressed concerns that policy does not appear to make use of the best available evidence.15,16 A large body of evidence from the social sciences literature suggests that the way issues are communicated (the “framing” of an issue) has considerable influence over policy actors’ perceptions, thereby influencing the development of the policy process.17–19 But there is a lack of empirical research on the importance of the framing of public health policy debates in the development of public health legislation, despite its potential importance.20

Studying the development of minimum unit pricing may help identify factors that could facilitate the adoption of evidence-informed policy. Such research may assist those engaged in advocacy and promote the effective utilization of research evidence, not just in alcohol policy, but in health-related policy more generally. As yet, there has been limited empirical research on the minimum unit pricing policy process.21 Public perceptions of minimum unit pricing are likely to influence its acceptability.22,23 However, we know little about how minimum unit pricing developed as a serious policy option in the first place.

Earlier research described the different ways that alcohol policy has been framed, particularly by the mass media, in order to understand the influence of different framings on audiences’ perceptions.24–27 These studies, however, have been predominantly descriptive and not related to the development of specific policies through empirical research. The importance of different framings to the policy process has been difficult to establish. Nonetheless, political science theory suggests that how a policy issue is defined may determine the extent to which it is viewed as amenable to intervention by policymakers, as well as the range of policy options that are considered.28–32

The United Kingdom, and Scotland in particular, is known to have a high level of alcohol-related harms compared with the rest of western Europe.33 While many factors—including historical, cultural, and social influences—underlie Scotland's consumption, a key driver behind the increasing rate of harms is the greater affordability of alcohol, with its price in off-license outlets (and especially supermarkets) considered particularly important.34 Epidemiological evidence has long established a consistent relationship among the increasing affordability of alcohol, population consumption, and alcohol-related harms.35,36 Measures to increase price (such as higher taxes) have therefore been used to address both public health concerns and ways to raise revenue. More recently, econometric modeling studies have indicated that measures that increase the price of the cheapest alcohol (such as minimum unit pricing) target those at greatest risk and result in greater public health benefits than do comparable increases in duties on alcohol.37,38 Before the development of minimum unit pricing, recent UK alcohol policy emphasized individual rather than population measures (such as pricing), with a focus on a government partnership with the alcohol industry to achieve “safe, sensible and social” consumption.39–42 Despite this, ideas about the importance of addressing the population's consumption have a long history, dating from at least the 1950s.43,44

The passage of minimum unit pricing legislation by the Scottish parliament was not straightforward. The first attempt, made in 2009 by the Scottish government, then led by the minority Scottish National Party (SNP), was unsuccessful,45 and the legislation passed only after the SNP obtained an overall majority in the 2011 Scottish parliamentary election. There has generally been a broad consensus in favor of minimum unit pricing among nonindustry policy stakeholders, such as the National Health Service, the police, and the third sector. Industry-related groups have been more divided, with the licensed trades (such as pubs and nightclubs) being generally supportive and most, but not all, producers and retailers (including supermarkets) being more hostile.46

Our study shows the importance of the framing of policy issues by illustrating how a change in the framing of alcohol as a policy issue facilitated the emergence of minimum unit pricing as a serious policy consideration. We first briefly summarize the key arguments presented by policy stakeholders for and against minimum unit pricing. We then analyze documents submitted by policy stakeholders to describe the different framings adopted and relate these to support for or opposition to minimum unit pricing. We then draw on our interview data to demonstrate why a change in the framing was considered important to enabling policymakers to pass minimum unit pricing legislation.

Methods

We used a qualitative case study design to investigate the framing of the minimum unit pricing debate at an early stage of the policy process.47,48 Qualitative case studies offer a detailed understanding of the development of a specific policy and allow an exploration of the interplay between the context in which a policy develops and the policy process itself. We combined these two sources of data to explore both the different framings represented in the policy debate and the influence of these framings on the policymaking process. We identified the framings primarily through an analysis of documents submitted in response to a Scottish parliamentary consultation, and we investigated the impact of the framings on the policy process through detailed interviews with stakeholders.

To investigate the relationship between competing framings and their potential influence on the policy debate, we used a theoretical framework for political argumentation,49,50 finding how the components required for a “reasonable” argument are represented by different stakeholders. These components included identifying representations of the current (starting) “circumstances” regarding the nature of the policy problem to be addressed, the desired “goal” that policy ought to pursue, the best “means” for attaining the goal, and the “values” underpinning the argumentative framework. Finally, we determined the alternatives and counterclaims articulated by actors for and against minimum unit pricing. The political science, sociology, and psychology literature all cite the importance of issue representation in understanding why actors behave in the way they do.18,29,51,52 In relation to policy development, the way that actors perceive the world is thought to influence their understanding of the policy issue and is the means by which they become aware of their own interests.29,52 In turn, their interpretation of the world influences both the choice of policy areas they focus on and the options they should consider. The use of a political science framework specifically designed to investigate issue definition in policy helps provide an analytical focus on this potentially important aspect of policymaking.

This process helped us explore the relationships among different framings of the policy debate and the arguments made for and against minimum unit pricing. For example, we established that if different ways of presenting the goal for policy were reflected in different framings of the starting circumstances and these different framings of the policy debate influenced the presentation of arguments regarding minimum unit pricing, the policy would appear more or less “reasonable.” We looked at reasons for the differences in the framing of policy, particularly the importance of a position on minimum unit pricing (supportive of or hostile to the measure) that had been decided before analysis. In this way, we were able to determine whether different means for achieving potentially different goals were supported by different framings of the policy problem. The characteristics of the individual or group seeking to influence the policy (the policy actor) also emerged as important during the analysis process.

Evidence Submission Documents

The standardized process in Scotland that proposals for new primary legislation undergo is intended to help ensure that new laws have been adequately scrutinized in a nonpartisan manner (for further details, see the Online Appendix).53 We obtained the documents for analysis from the first information-gathering stage of this scrutiny process (by the Health and Sport Committee), in order to investigate the influence of framing early in the process. The committee asked stakeholders for written evidence submissions in November 2009.54 Evidence submission documents were provided by 185 actors, with many submitting more than 1 document (eg, enclosing additional supportive documents or reports).55 A total of 47 stakeholders (67 documents) who had provided written evidence went on to present oral evidence to the committee. Those providing oral evidence were chosen by the committee to reflect the range of interests represented overall in the written evidence submissions, and we therefore felt that these documents well captured the breadth of the stakeholders’ views. We also considered it likely that those views represented in both the oral and written evidence submissions would have the greatest influence on the framing of the minimum unit pricing policy debate.

Analysis of Documents

We first reviewed all the submitted documents to determine the range of positions adopted by different stakeholders with respect to minimum unit pricing. One of us (Srinivasa Vittal Katikireddi) analyzed in depth all the documents submitted to the committee by the 47 stakeholders who presented both verbal and written evidence, and Shona Hilton checked them. We next coded the documents thematically, with the first phase of analysis coding the information by means of descriptive inductive codes using NVivo 9. This allowed us to summarize the different arguments for and against minimum unit pricing. After the initial coding, we used more conceptual codes, including codes for the different components of the political argumentation framework just described,49 as well as allowing for emergent conceptual codes. Following this coding process, we identified higher-order conceptual themes, explaining the differences through a constant comparative method.56

Interview Data

To investigate the impact of different framings on the policy process, as well as to provide contextual information and allow the triangulation of results, we conducted 36 semistructured interviews between March 2012 and January 2013 with politicians, civil servants, researchers, minimum unit pricing advocates, and industry representatives (see the Online Appendix). We purposively selected those participants who represented a range of positions on support for minimum unit pricing and other dimensions (including political party for politicians, subsector in alcohol-related industries for industry actors, type of advocacy organization, and government department for civil servants). We identified these participants through a review of the policy documents, analysis of the evidence submission documents, and snowball sampling (in which we asked the interviewees to suggest other interviewees). We continued these interviews until no new major themes emerged in the data and we had adequate diversity in the sample. For reasons of confidentiality, we cannot provide further details of the breakdown of participants beyond each one's broad sector. But we did have a diverse range of interviewees in all these groups, and they exhibited a range of viewpoints on minimum unit pricing.

Our interviews were guided by questions on the framing of alcohol as a policy problem, perceptions of the different actors’ roles (including their own role), arguments regarding minimum unit pricing, and reasons to establish minimum unit pricing. The interviews typically lasted around 45 minutes to 1 hour. Because the limited number of potential participants for this study increased the risk of their being identified and could make their recruitment difficult, we used a collaborative process to ensure confidentiality. Details about this process and considerations of reflexivity are available in the Online Appendix.

Interview Analysis

After the interviews were transcribed, we reread them repeatedly, coded them thematically, and analyzed them using iterative comparisons of the document data and interview data, followed by recoding emergent themes. The principle of the constant comparative method was used to help identify explanations for patterns in the data while also paying appropriate attention to deviant or contradictory data.

The study was reviewed by and obtained ethical approval from the University of Glasgow's College of Medicine and Veterinary Science research ethics committee.

Results

Overview

Of the 185 stakeholders who submitted evidence to the consultation, the vast majority were explicitly in favor of minimum unit pricing (n = 109), with only 27 explicitly hostile (for further details, see the Online Appendix). Almost all in the latter group were industry-related stakeholders.

Our detailed descriptive analysis of the 67 evidence submission documents (submitted by 47 stakeholders) covered a broad range of arguments about the likely consequences for and against minimum unit pricing, which are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

A Summary of Arguments for and Against Minimum Unit Pricing (MUP), Presented in Evidence Submission Documents to the Scottish Parliament's Health and Sport Committee

| Themes | Arguments for Minimum Unit Pricing | Arguments Against Minimum Unit Pricing |

|---|---|---|

| Drinking patterns | ||

| Changes in strength of alcoholic drinks | Strength of alcoholic drinks may be reduced to allow prices to be lowered, hence encouraging the availability of low-strength drinks. | Strength of alcoholic drinks may be increased (or they may be marketed more heavily) as they become more profitable. |

| Moving to licensed premises | Moving to licensed premises (which is a safer regulated drinking environment) is encouraged as price differential is lessened. | Drinking at licensed premises is not necessarily safer than drinking at home.Changes in drink environment reflect culture changes, not price differential. |

| Inequalities | ||

| Regressive | Lower-income groups are less likely to buy alcohol, so this is not regressive. | Lower-income groups may no longer be able to afford alcohol. |

| Alcohol contributes to health inequalities. | ||

| Prices of nonalcohol products (which are healthier) may be reduced, as supermarkets no longer use alcohol as loss leaders. | ||

| Household impacts | Households with dependent drinkers may experience greater poverty if the dependent drinkers continue to consume the same amount of alcohol. | |

| Economic implications | ||

| Job changes | MUP is unlikely to result in long-term job losses. | MUP may cause job losses in broad range of alcohol-related industries. |

| Economic impact | MUP may reduce work absence and result in economic gains. | MUP will hurt the economy because of its effect on alcohol-related industries. |

| Government revenue | Increased economic growth will help government revenue. | In contrast to government raising revenue from alcohol taxation, increased revenue from MUP will go to the private sector. |

| Alternatives | ||

| Price interventions | MUP has a greater effect on health than other price interventions. | Ban on below-cost sales or tax increases are less trade-restrictive and result in government revenue. |

| Nonprice interventions | Many nonprice interventions (especially education) are ineffective. Other interventions should be used alongside MUP. | Nonprice interventions, especially education, are necessary. |

| Alcohol market changes | ||

| Home brew, cross-border, and Internet sales | MUP is unlikely to result in large changes to home brew, cross-border, or Internet sales. | Home brew, cross-border, and Internet sales will increase because of MUP. |

| Black market and illegal alcohol | Illegal alcohol should be tackled by improved policing. | Sales of black market and illegal alcohol are increasing and will increase further. |

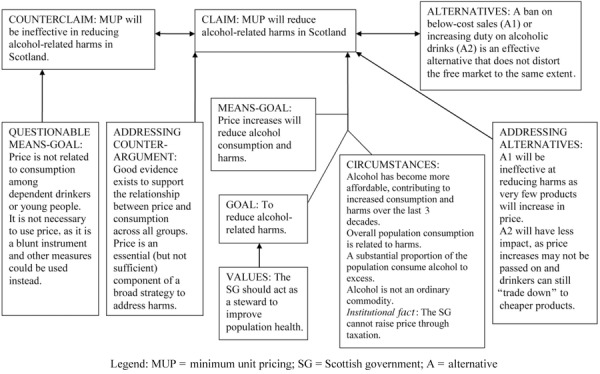

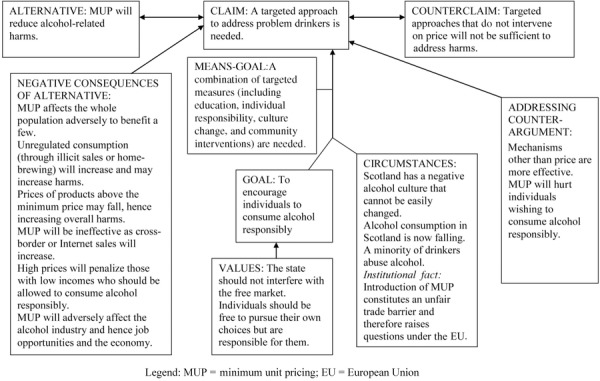

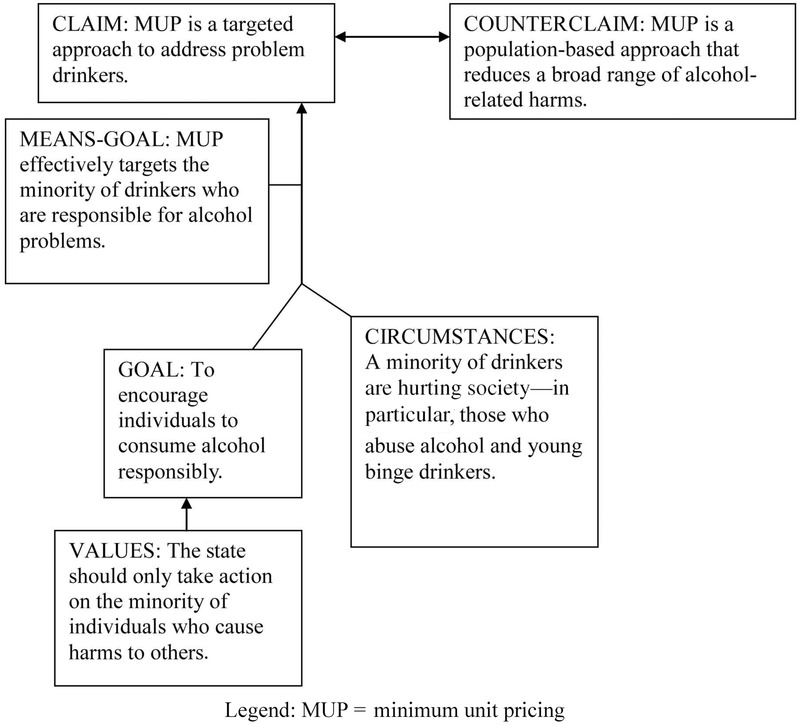

The various stakeholders in the policy debate portrayed alcohol as a policy issue in many different ways. While not all the aspects of the different framings were evident in every document, 2 overarching competing framings were apparent and were used by policy stakeholders to help support their position on minimum unit pricing: a framing that presented minimum unit pricing in a positive manner and a critical framing that was used only by industry actors (Figures 1 and 2). In addition, a third hybrid framing was adopted by industry actors who supported minimum unit pricing but retained most aspects of the critical frame (Figure 3). Next we describe these framings, related to support for and opposition to minimum unit pricing. Then we use the interview data to consider these competing framings and to show that those advocating for public health measures sought to deliberately change the framing of the policy problem.

Figure 1.

A Framing Used by Nonindustry Actors to Support the Claim That Minimum Unit Pricing Is an Effective Policy

Figure 2.

A Critical Framing to Support the Counterclaim That Targeted Approaches Should Be Pursued

Figure 3.

A Framing Used by Industry Actors to Support the Claim That Minimum Unit Pricing Is a Targeted Policy

Presenting a Favorable Case for Minimum Unit Pricing

Those stakeholders not associated with alcohol-related industries (defined widely to include retailers such as supermarkets) presented a persuasive framing for minimum unit pricing in a number of complementary ways (see Figure 1).

Definition of Current Circumstances

The “current circumstances” highlighted by nonindustry advocates of minimum unit pricing tended to present alcohol as a policy priority that was associated with a wide range of harms arising from population (and not just individual) overconsumption.57–65 This presentation helped justify a population-based approach.

Nonindustry advocates consistently referred to the diverse range of both health and nonhealth harms in submitted documents,57–65 presenting health harms as including a wide range of chronic as well as acute harms. While many actors referred to “binge drinking” by young drinkers, they appeared to deliberately emphasize those harms arising from consumption among the wider population. In contrast to the industry framing (presented later), which focused on issues of social disorder, the nonindustry actors highlighted the multisectoral nature of alcohol as a policy issue. For example, BMA Scotland, the body representing medical doctors, stated:

Alcohol is related to more than 60 types of disease, disability and injury. In 2007/08 there were 42,430 alcohol related discharges from general hospitals in Scotland. … Regular heavy alcohol consumption and binge drinking are associated with physical problems, antisocial behaviour, violence, accidents, suicide, injuries and road traffic crashes. Among adolescents, they can also affect school performance and crime. Alcohol misuse is associated with a range of mental disorders and can exacerbate existing mental health problems. Adolescents report having more risky sex when they are under the influence of alcohol; they may be less likely to use contraception and more likely to have sex early or have sex they later regret. … Drinking too much on a regular basis increases the risk of damaging one's health, including liver damage, mouth and throat cancers and raised blood pressure. Unhealthy patterns of drinking by adolescents may lead to an increased level of addiction and dependence on alcohol in adulthood.59

This framing emphasizes that the overall population is being hurt, including by the adverse financial consequences of the population's overconsumption of alcohol. It is not just harms broadly articulated that affect the overall society; rather, the entire population, not any specific subgroup(s), is responsible for alcohol-related harms. For example, Children in Scotland stated:

We support the Scottish Government's goal of significantly reducing overall alcohol consumption, binge drinking and the extraordinary social, economic and health costs of alcohol use/misuse throughout our nation. The Scottish Government is correct in identifying the magnitude of alcohol-fuelled problems and the unhealthy relationship with alcohol across Scottish society.63

By extending the range of harms related to alcohol overconsumption, nonindustry advocates were better able to locate responsibility for alcohol-related harms across a broad range of the population, that is, represent alcohol as a population issue rather than an individual health issue.

Epidemiological data were presented in a way that not only demonstrated the large burden of alcohol-related harms but also represented a “crisis” requiring urgent action.59,61,66–68 A study published by Leon and McCambridge in The Lancet was widely used to illustrate the considerable growth in alcohol-related health harms in Scotland, which contrasted unfavorably with the rest of western Europe.33 Advocates tended to use relatively “hard” epidemiological indicators, such as mortality, hospital admissions, and total alcohol sales data, to describe trends rather than self-reported survey data.59,69,70 For example, the advocacy group Scottish Health Action on Alcohol Problems noted: “Alcohol-related harm in Scotland has increased exponentially during the past few decades. In the ten years between 1992 and 2002, alcohol-related mortality went up by more than 100%.”66 Therefore, the starting circumstances were characterized by a broad range of escalating harms that were hurting all of Scottish society. The cause of this “crisis” that required intervention was overconsumption by the whole population, not by just a small minority.

The Goal, Means-Goal, and Values for Policy

Advocates tended to present the goal of alcohol policy as “reducing alcohol-related harm.”57–60,63,64,66–69 Thus, many documents linked the breadth of harms arising from alcohol consumption to the breadth of the population affected and argued that the best means of reducing alcohol-related harms was to cut the population's consumption: “Reducing overall alcohol consumption in the population is a necessary prerequisite to reducing alcohol-related harm in Scotland and an effective alcohol policy requires whole population measures including controls on price and availability.”71 This framing presents minimum unit pricing as “necessary” to achieve the goal of “reducing alcohol-related harm.” Advocates used epidemiological evidence drawing on systematic reviews to demonstrate the robust relationship of alcohol price, population consumption, and population harms. This evidence therefore helped strengthen the argument that it is necessary to reduce population consumption in order to reduce alcohol-related harms and that it is therefore “not a case of penalising the majority in order to discourage the minority,”57 as effective policy action requires a reduction in population consumption. Underpinning this argument are values that the Scottish parliament has a duty to improve the population's health and to intervene in economic markets when they are not functioning in the public interest. In the words of one alcohol epidemiologist,

If as well as such individualistic arguments there is some public ethos (caring externalities) that the state does have a stewardship role in individual behaviour there could be gains even if the impact of the policy was only on improving the quality and quantity of life of the hazardous and harmful drinker. … The first question that the Scottish parliament has to decide is, does it take on a role of stewardship or not. The concept of stewardship implies that liberal states have a duty to look after the important needs of people both individually and collectively. The stewardship-guided state recognizes that a primary asset of a nation is its health: higher levels of health are associated with greater overall well-being and productivity.68

In addition, many actors from a broad variety of backgrounds who were in favor of minimum unit pricing emphasized that alcohol is “no ordinary commodity” and therefore should not be the subject of market forces (in direct contrast to the critical framing described next).57,67,72–74

Based on this framing, minimum unit pricing was portrayed as an effective population health measure. In addition, those in favor of minimum unit pricing also explained that the policy was a targeted population measure, as it affected mainly those in the population who were drinking most problematically. This explanation helped address arguments for alternative price measures (particularly increasing alcohol duty), as they would less effectively target those at greatest risk of health harms and thus the extent of public health benefits would be comparably smaller.

Presenting an Unfavorable Case for Minimum Unit Pricing

Hostile actors, almost all of whom were industry related, tended to present the policy issue in a markedly different way.

Definition of Current Circumstances

First, they disputed the extent to which the alcohol issue represented a crisis requiring policy intervention.75–77 An important source of evidence to justify this argument was their focus on recent (rather than longer-term) trends in self-reported survey data:

A significant minority of the population in the UK and, to a greater extent, in Scotland have unhealthy relationships with alcohol. We note, however, that the Scottish Government continues to justify population-wide control measures, such as pricing restrictions, by claiming that “up to 1 in 2 men” are estimated to be regularly drinking over sensible drinking guidelines. The 2008 Scottish Health Survey includes updated estimates of the proportions of men and women exceeding the weekly sensible drinking guidelines. In comparison with 2003, these show a fall from 34% to 30% for men and from 23% to 20% for women. This makes the suggestion that 50% of men might be exceeding the guidelines seem unlikely.77

The industry framing centered on a narrower range of adverse alcohol impacts.75,76,78–87 In contrast to the broad scope of alcohol-related harms described by nonindustry advocates, the industry actors emphasized harms related to specific minority groups within the population. For example, “It is misplaced to focus on the availability and affordability of alcohol as the sole and root cause of misuse. Real drivers behind harmful drinking, binge drinking behaviour and under 18's alcohol misuse tend to get overlooked as a consequence.”86 This quotation is typical of the industry's portrayal of alcohol as a policy issue and illustrates its focus on “binge drinking” by young people, as well as other groups engaged in “alcohol abuse.” While nonindustry actors presented alcohol as a multisectoral policy concern, industry actors linked fewer issues to alcohol, with relatively little consideration of adverse financial impacts. Attributing the narrow scope of harms to specific groups of the population helped justify their pursuit of a targeted approach.

The Goal, Means-Goal, and Values for Policy

Those critical of minimum unit pricing presented the policy goal in a different way than did those in favor of it. While the latter argued that the goal should be to reduce alcohol-related harms, industry presented a goal of encouraging the “responsible consumption” of alcohol.75–77,79–81,85–90 It is important that this presentation helped encourage a focus on individual consumption and hence individual responsibility. For example, “Our aim is to ensure that moderate consumption continues to be part of normal healthy life in Scotland, and that misuse is regarded as unacceptable behaviour.”75 Those critical of minimum unit pricing justified their position by arguing that a minority of the population was responsible for the few harms to be addressed, and so it was appropriate to target this group rather than the broader population. Action must be “targeted” and therefore should not “punish” those behaving “responsibly.” This lays the ground for the actions that are admissible in this frame, thereby making minimum unit pricing unjustifiable from this perspective. Instead, those critical of minimum unit pricing presented their policy responses as appropriate if they targeted the minority responsible for these harms, as illustrated by this alcohol producer organization: “The sledgehammer is not the best tool for nut cracking! It is time to search out the correct policies for changing the habits of a minority whilst coercing the majority to understand the dangers of excess.”91

These critics suggested alternatives that would not affect overall levels of population consumption but instead would target those who “misused” alcohol, with price measures such as a ban on below-cost sales (which were presented as interfering less in the alcohol market's functioning).86,91,92 They also frequently recommended nonprice alternatives, with education-based measures particularly prominent.75–77,79,81,82,85,87 Underlying the goal of achieving responsible consumption was often the means-goal of “cultural change.” In the words of the supermarket chain Asda, “We believe that there is a requirement for a fundamental cultural change in society's relationship with alcohol. Therefore while we welcome the high priority given by the Scottish Government and Parliament to tackling alcohol misuse, we believe that the debate has been too focussed on pricing mechanisms.”76 This framing was underpinned by values that prioritize freedom from the state and individual responsibility,80,84,85,87,93,94 as exemplified by Co-operative Supermarkets in their submission:

Clearly the change in culture being sought in Scotland, can only be achieved with a holistic approach involving a broad spectrum of stakeholders, bearing in mind that key to a change in culture does require some individual responsibility. … We do not support the introduction of minimum pricing for alcohol products as this goes against the whole ethos of open competition and would limit consumer choice.85

This framing therefore defined alcohol as a policy issue in narrow terms. The harms that occur were presented as largely arising from the actions of a minority, who therefore should be the subject of targeted strategy. The overall purpose of alcohol policy is to create a society with responsible consumption in which the state does not interfere unduly.

A Hybrid Framing—Industry in Favor of Minimum Unit Pricing

As we noted at the beginning of this article, not all industry actors were hostile to minimum unit pricing; indeed, those that represented the licensed trade (such as pubs and nightclubs) often were supportive, as were a minority of producers and retailers.89,90,92,95 Despite their supportiveness, though, these actors tended to maintain aspects of the critical framing.

Definition of Current Circumstances

Industry actors who favored minimum unit pricing tended to describe the current circumstances in a way similar to that of other industry actors but different from that of other actors who favored it. That is, they stated that only a minority of the population overconsumed alcohol and argued that it was reasonable to use minimum unit pricing as a measure, since it targeted this population group. The policy issue was framed in terms emphasizing a narrow range of harms in a small minority of the population. For example, one brewer stated,

We recognise that there is an issue of overconsumption of alcohol among a minority of consumers, and acknowledge that the Scottish Government is working to try to combat this problem. In particular, there is an issue with a small group of consumers who purchase cheap alcohol in bulk, drink excessively at home and then go out into pubs and clubs and get into difficulties. We believe that, if implemented appropriately, minimum pricing could be part of the solution by increasing the price of alcohol, particularly of high strength products and is one way of addressing the alcohol abuse issues that we face in Scotland.89

This aspect of framing the problem is largely consistent with the critical framing described earlier.

The Goal, Means-Goal, and Values for Policy

The goal of alcohol policy continued to be presented as encouraging responsible consumption and not addressing public health harms, as demonstrated by Molson Coors in their submission:

Keeping in mind that there is no one quick fix for addressing alcohol harm, Molson Coors remains committed to keep working together with the Scottish government and others to make sure that the irresponsible alcohol consumption is addressed. We believe that reducing alcohol abuse is a desirable and achievable goal. We need efficient policies to target alcohol harm without punishing the responsible consumer.90

The goal therefore remains to encourage responsible consumption and address “alcohol abuse.” Actors justifying minimum unit pricing argued that it was better targeted than other measures, rather than addressing population overconsumption. The values underpinning this framing retain the importance of not “punishing the responsible consumer.” It therefore helps the pursuit of minimum unit pricing while maintaining a framing that does not acknowledge reducing population consumption as necessary for public health. In other words, the framing focuses on presenting minimum unit pricing as a targeted approach that does not affect the broader population, rather than a population-based approach that more greatly affects those at increased risk.

A Change in Policy Framings

Our interview data supported the different framings just described. In addition, the interviewees repeatedly (and often spontaneously) referred to the change in the framing of the policy debate over time. In the words of 2 interviewees,

Industry: “I guess ultimately that is where the debate has changed. It has become, as the debate's moved more to almost this kind of population health approach, population impact approach, there is a bit where it has moved away from personal responsibility.”

Civil servant (Scotland): “I think in terms of Scottish Government policy the crucial change was to sort of shift to the whole population approach and away from the sort of notion that it's people kind of causing a rumpus on a Saturday night. That's one manifestation of the problem, but actually the impact's much more widespread and profound, you know, and it's impacting on our children.”

In addition to the broad consensus that the framing of the policy debate in Scotland had changed, the interview data also indicated that this change represented a deliberate strategy by public health advocates to influence the policy process. In the words of 2 different interviewees involved in the policy process,

Advocate: “The first thing we have to do in order to create … a climate that would be conducive to discussions about minimum unit pricing, was to change the frame of the alcohol problem. Because the frame of the alcohol problem, which was the industry frame, if you accept that frame of the problem then, you know, you will not support population measures, ’cuz you think the problem is youth binge drinkers or whatever.”

Advocate: “We were advocating at that point … framing alcohol in the public health paradigm which involves a whole population approach, and by that meaning you reduce—you don't just target individuals who are drinking to excess—you aim to reduce the whole population, the average population alcohol consumption and mechanisms like price and availability will be doing that sort of thing, and using epidemiological thinking—you shift the curve to the left, therefore, those at the tail end, you know, a disproportionate reduction and they're very heavy drinkers and so on.”

The interview data also suggest that this shift in the framing of the debate is unlikely to be coincidental but seemed to be important (and might even be the “key”) to allow the emergence of minimum unit pricing in Scottish policy. In the words of another advocate,

Advocate: “So I think it's been, over the last ten years it's been an issue—the problem was they didn't want to take a public health approach. The Labour administration did not take a public health approach. And this has been the, sort of, the major, major step forward has been … persuading the SNP that this was, you know … ‘everyone's drinking too much.’ Just simply saying that, which is something that Labour would never say. They were very much, you know, still wanting to talk about responsible drinkers, you know, it's … it's … don't want to penalise the majority, you know, working class pleasures, all this kind of discourse. And I think that's been the key so, although it's been a major policy issue for ten years, the key has been this switch, just, almost one sentence, you know—taking a population approach.”

Changing the framing of the policy debate did not appear to be straightforward and required those advocating public health action to continually challenge the industry framing. Many advocates saw the importance of securing a shift in framing as an important victory, especially the articulation of a population health framing in official Scottish government policy documents.

Discussion

Our study has demonstrated that a change in the policy debate's framing appears to have been important because it allowed policymakers to seriously consider population-based measures, including minimum unit pricing, as feasible policy interventions. We identified competing framings of the policy issue through a detailed qualitative analysis of policy documents and in-depth interviews with policy stakeholders. Industry-related groups tended to frame alcohol as a policy issue in narrow terms, relating alcohol to a small range of harms attributable to consumption by minority groups (frequently described as binge drinkers, young people, and a minority that misuse alcohol). In contrast, nonindustry actors broadened the scope of harms related to alcohol and therefore were able to characterize alcohol as a policy issue that adversely affected all of Scottish society. By doing this, they argued that alcohol was no ordinary commodity and that population-based approaches (including minimum unit pricing) were necessary to address the population overconsumption.96 Combining qualitative interview data with document analysis allowed us to go beyond demonstrating the existence of competing framings of the policy debate. In particular, we were able to establish that in this case, the emergence of minimum unit pricing appears to have been facilitated by a change in framings resulting from efforts by public health advocates. To our knowledge, this is the first published example empirically demonstrating the use of a change in framing as a deliberate strategy to change high-profile public health policy.

The framing of the policy debate by industry stakeholders who supported minimum unit pricing is noteworthy. Presenting minimum unit pricing in an industry framing broadened the support for the specific measure of minimum unit pricing while simultaneously reinforcing a framing that disputes the need to reduce overall population consumption. This subtle change in industry framing may therefore curtail possibilities for future population-based interventions, such as limits to marketing or alcohol availability.

Our research also showed the diverse and contradictory ways that research evidence can be presented within a policy debate.97 The availability of different sources of epidemiological data and the choice of different time periods over which to illustrate trends helped policy actors present the policy issue in markedly different ways—as either a crisis requiring urgent action or a problem that was being resolved.

Our study has a number of strengths. In order to gain appropriate depth in our understanding of the policy process, we concentrated on the development of a single policy of major public health importance. The process used by the Scottish Parliamentary Health and Sport Committee allowed us to access a diverse range of evidence submission documents for analysis, a resource often not available in studies of the policy process. We conducted qualitative interviews with many different policy stakeholders. By carrying out the interviews over a long period of time and as a result of the research team's contacts in this area, we achieved relatively high rates of participation, with excellent coverage of the range of stakeholders we wanted to interview. We analyzed the data in considerable detail, with double-coding and cross-case comparison, particularly in contradictory cases. We also used an argumentation framework specifically designed to help relate framing to the presentation of arguments in a policy debate. This is, to our knowledge, the first public health use of an explicitly political argumentation framework.49

Our study also has a number of limitations. First, this case study investigates the development of a single policy, so generalization to other countries and policy areas may be limited. Second, even though we obtained high-quality interview data from many people intimately involved in the policy process, we were unable to interview every individual that we would have liked to. Third, our research necessarily was conducted after the initial emergence of minimum unit pricing. It therefore is possible that the interviewees’ views of the policy process may have been affected by subsequent changes in the policy landscape, hence reflecting their rationalizations rather than their actual perceptions. Similarly, the interviewees may have deliberately sought to misrepresent or, more likely, to be partial in their descriptions of the policy process, although our assurances of confidentiality should have reduced this risk. Last, our confidentiality considerations prevented us from revealing the context in which specific interviews took place. Although we paid due attention to issues of positionality and reflexivity, we were unable to present the full details in this article.

Changes in the framing of the policy problem are reflected by Scottish and, to a lesser extent, UK government policy documents. In contrast to the focus on individual responsibility in previous government policy, which we noted at the beginning of this article, the most recent Scottish government policy, Changing Scotland's Relationship with Alcohol,98 states:

Alcohol misuse is no longer a marginal problem, with up to 50% of men and up to 30% of women across Scotland exceeding recommended weekly guidelines. That's why we are aiming, consciously, to adopt a whole population approach. This isn't about only targeting those with chronic alcohol dependencies. … Our approach is targeted at everyone, including the “ordinary people” who may never get drunk but are nevertheless harming themselves by regularly drinking more than the recommended guidelines. If we can reduce the overall amount that we all drink in Scotland, and if we can change the way we drink, then we will all reap the benefits.

Recent work has highlighted the importance of considering the framing of health-related policy but has generally failed to directly relate framing to the policy process.99–101 Some researchers have gone further, noting the fierce contestation in the language used in policy documents.102 Our research adds to this literature by showing how framing can influence the perceived acceptability of a policy intervention to policymakers.

While we have identified a change in framing as an important component of the development of minimum unit pricing, we do not wish to suggest that this represents the only reason for the policy's emergence. Political science theories indicate that the policy process is complex, with several theories highlighting the importance of several factors coming together to facilitate a policy's development.103,104 Questions therefore remain about the key contextual factors that allowed the emergence of a supportive framing. Other recent research on minimum unit pricing centered on the importance of the institutional landscape,21 with the specific responsibilities of the Scottish parliament providing a reason for focusing on a public health perspective and thereby echoing experiences of the legislation banning smoking in public places.105 Furthermore, we believe that Scotland has shown leadership in public health and that there are political advantages in doing so, particularly in the context of a Scottish independence debate.106 Research evidence appears to have been important to the policy's development. In particular, econometric modeling was a helpful way of incorporating the findings of research into policy debates,107 and in the case of minimum unit pricing, the Sheffield alcohol policy model appears to have been influential as well.108 The divergence in the interests of the different alcohol-related industries noted earlier might favor the adoption of a public health perspective,46,109 despite industry interests’ selective use of evidence and vigorous lobbying efforts.110,111 Finally, the mass media appears to have communicated key arguments in favor of minimum unit pricing, which is likely to increase public support.112,113

This study has a number of important implications for health professionals and researchers who are engaged in policy. The research suggests that public health advocates need to pay attention to the framing of policy debates and concentrate on how policymakers understand a policy issue in order to influence policy. For example, the findings suggest that population-based interventions may be viewed more favorably if the full range of harms across the entire population is presented to policymakers. The success of legislation creating smoke-free public places is another example of the importance of presenting the full breadth of harms to policymakers.114 In relation to smoke-free legislation, an appreciation of occupation-related harms may have allowed the policy issue to be conceptualized in a new way, which helped change the policy. Empirical research will be required to investigate the effectiveness of reframing as an intentional strategy for public health policy.

Acknowledgments

This study received no dedicated funding. At the time the study was conducted, Srinivasa Vittal Katikireddi and Lyndal Bond were funded by the Chief Scientist Office at the Scottish Health Directorates as part of the Evaluating Social Interventions programme at the MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit (MC_U130059812 and MC_UU_12017/4). Shona Hilton was funded by the Medical Research Council as part of the Understandings and Uses of Public Health Research programme (MC_U130085862 and MC_UU_12017/6). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

The authors would like to thank the interviewees for participating in this research. They would also like to thank Professor Dame Sally Macintyre at the MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit and Martin Higgins at NHS Lothian for comments on a draft of the manuscript; Claire Niedzwiedz for proofreading the manuscript; and the reviewers for helpful comments that have strengthened the manuscript.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/10.1111/(ISSN)1468-0009:

Disclaimer: Supplementary materials have been peer-reviewed but not copyedited.

Online Appendix

References

- 1.Scottish Parliament. Alcohol (Minimum Pricing) (Scotland) Act 2012 (asp 4) Edinburgh, Scotland: Stationery Office Limited; May 24, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katikireddi SV, McLean JA. Introducing a minimum unit price for alcohol in Scotland: considerations under European law and the implications for European public health. Eur J Public Health. 2012;22(4):457–458. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cks091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scotch Whisky Association. Scotch whisky industry challenges minimum pricing of alcohol. 2012. http://www.scotch-whisky.org.uk/news-media/news/scotch-whisky-industry-challenges-minimum-pricing-of-alcohol/#.UGTOkVGgSSo. Accessed September 27, 2012.

- 4.Government HM. The Government's Alcohol Strategy. London, England: HM Government; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization (WHO) Europe. European Action Plan to Reduce the Harmful Use of Alcohol 2012-2020. Copenhagen, Denmark: WHO; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fogarty A, Chapman S. What should be done about policy on alcohol pricing and promotions? Australian experts’ views of policy priorities: a qualitative interview study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):610. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macintyre S. Inequalities in Health in Scotland: What Are They and What Can We Do About Them. Glasgow, Scotland: MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bambra C, Joyce KE, Bellis MA, et al. Reducing health inequalities in priority public health conditions: using rapid review to develop proposals for evidence-based policy. J Public Health (Oxf) 2010;32(4):496–505. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdq028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Attaran A, Pang T, Whitworth J, Oxman A, McKee M. Healthy by law: the missed opportunity to use laws for public health. The Lancet. 2012;379(9812):283–285. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60069-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fooks GJ, Gilmore AB, Smith KE, Collin J, Holden C, Lee K. Corporate social responsibility and access to policy élites: an analysis of tobacco industry documents. PLoS Med. 2011;8(8):e1001076. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beaglehole R, Bonita R, Horton R, Adams O, McKee M. Public health in the new era: improving health through collective action. The Lancet. 2004;363(9426):2084–2086. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16461-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bero LA, Montini T, Bryan-Jones K, Mangurian C. Science in regulatory policy making: case studies in the development of workplace smoking restrictions. Tob. Control. 2001;10(4):329–336. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.4.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hernández-Aguado I. The tobacco ban in Spain: how it happened, a vision from inside the government. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2013;67(7):542–543. doi: 10.1136/jech-2012-201933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weishaar H, Collin J, Smith K, Grüning T, Mandal S, Gilmore A. Global health governance and the commercial sector: a documentary analysis of tobacco company strategies to influence the WHO framework convention on tobacco control. PLoS Med. 2012;9(6):e1001249. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katikireddi SV, Higgins M, Bond L, Bonell C, Macintyre S. How evidence based is English public health policy. BMJ. 2011;343:d7310. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d7310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Macintyre S. Evidence based policy making. BMJ. 2003;326(7379):5–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7379.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scheufele DA. Framing as a theory of media effects. J. Commun. 1999;49(1):103–122. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Entman RM. Framing: toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J. Commun. 1993;43(4):51–58. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weiss J. The powers of problem definition: the case of government paperwork. Policy Sciences. 1989;22(2):97–121. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edwards G. The trouble with drink: why ideas matter. Addiction. 2010;105(5):797–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holden C, Hawkins B. “Whisky gloss”: the alcohol industry, devolution and policy communities in Scotland. Public Policy Adm. 2013;28(3):253–273. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lonsdale A, Hardcastle S, Hagger M. A minimum price per unit of alcohol: a focus group study to investigate public opinion concerning UK government proposals to introduce new price controls to curb alcohol consumption. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):1023. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chalmers J, Carragher N, Davoren S, O'Brien P. Real or perceived impediments to minimum pricing of alcohol in Australia: public opinion, the industry and the law. Int J Drug Policy. 2013;24(6):517–523. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith KC, Twum D, Gielen AC. Media coverage of celebrity DUIs: teachable moments or problematic social modeling. Alcohol Alcohol. 2009;44(3):256–260. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agp006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dorfman L. Studying the news on public health: how content analysis supports media advocacy. Am J Health Behav. 2003;27(Suppl. 3):S217–S226. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.27.1.s3.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Casswell S. Public discourse on alcohol. Health Promot Int. 1997;12(3):251–257. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hansen A, Gunter B. Constructing public and political discourse on alcohol issues: towards a framework for analysis. Alcohol Alcohol. 2007;42(2):150–157. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agl114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Majone G. Evidence, Argument and Persuasion in the Policy Process. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stone DA. Policy Paradox: The Art of Political Decision Making. New York: Norton; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riker WH. The Art of Political Manipulation. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sabatier PA. Theories of the Policy Process. Cambridge, MA: Westview; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sabatier P. An advocacy coalition framework of policy change and the role of policy-oriented learning therein. Policy Sciences. 1988;21(2–3):129–168. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leon DA, McCambridge J. Liver cirrhosis mortality rates in Britain from 1950 to 2002: an analysis of routine data. The Lancet. 2006;367(9504):52–56. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)67924-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robinson M, Catto S, Beeston C. Monitoring and Evaluating Scotland's Alcohol Strategy (MESAS): Analysis of Alcohol Sales Data, 2005–2009. Glasgow, Scotland: NHS Health Scotland; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Booth A, Meier P, Stockwell T, Sutton A, Wilkinson A, Wong R. Independent Review of the Effects of Alcohol Pricing and Promotion—Part A: Systematic Reviews. Sheffield, England: ScHARR, University of Sheffield; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wagenaar AC, Salois MJ, Komro KA. Effects of beverage alcohol price and tax levels on drinking: a meta-analysis of 1003 estimates from 112 studies. Addiction. 2009;104(2):179–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Purshouse RC, Meier PS, Brennan A, Taylor KB, Rafia R. Estimated effect of alcohol pricing policies on health and health economic outcomes in England: an epidemiological model. The Lancet. 2010;375(9723):1355–1364. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60058-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Purshouse R, Meng Y, Rafia R, Brennan A, Meier P. Model-Based Appraisal of Alcohol Minimum Pricing and Off-Licensed Trade Discount Bans in Scotland: A Scottish Adaptation of the Sheffield Alcohol Policy, Model Version 2. Sheffield, England: ScHARR, University of Sheffield; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anderson P. A safe, sensible and social AHRSE: New Labour and alcohol policy. Addiction. 2007;102(10):1515–1521. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prime Minister's Strategy Unit. Alcohol Harm Reduction Strategy for England. London, England: Cabinet Office; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scottish Executive. A Plan for Action on Alcohol Problems. Edinburgh, Scotland: Scottish Executive; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hackley C, Bengry-Howell A, Griffin C, Mistral W, Szmigin I. The discursive constitution of the UK alcohol problem in Safe, Sensible, Social: a discussion of policy implications. Drugs: Educ, Prev & Policy. 2008;15(s1):61–74. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berridge V, Thom B. Research and policy: what determines the relationship. Policy Studies. 1996;17(1):23–34. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baggott R. Alcohol, politics and social policy. J. Soc. Policy. 1986;15(04):467–488. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scottish Parliament. Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill [as passed]; 2010.

- 46.Holden C, Hawkins B, McCambridge J. Cleavages and co-operation in the UK alcohol industry: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):483. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marsh D, Stoker G. Theory and Methods in Political Science. 3rd ed. Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Macmillan; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Walt G, Shiffman J, Schneider H, Murray SF, Brugha R, Gilson L. “Doing” health policy analysis: methodological and conceptual reflections and challenges. Health Policy Plan. 2008;23(5):308–317. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czn024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fairclough I, Fairclough N. Political Discourse Analysis: A Method for Advanced Students. Oxon, England: Routledge; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fairclough I, Fairclough N. Practical reasoning in political discourse: the UK government's response to the economic crisis in the 2008 pre-budget report. Discourse & Society. 2011;22(3):243–268. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shaw SE. Reaching the parts that other theories and methods can't reach: how and why a policy-as-discourse approach can inform health-related policy. Health. 2010;14(2):196–212. doi: 10.1177/1363459309353295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Surel Y. The role of cognitive and normative frames in policy-making. J Eur Public Policy. 2000;7(4):495–512. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Scottish Parliament. Annex E: Stages in the Passage of a Public Bill. Edinburgh, Scotland: Scottish Parliament; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Health and Sport Committee. Edinburgh, Scotland: Scottish Parliament; 2010. 5th Report, 2010 (Session 3): Stage 1 Report on the Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Health and Sport Committee. 5th Report, 2010 (Session 3): Stage 1 Report on the Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill. Vol. 2: Evidence. Annexe B: oral evidence and associated written evidence. http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/s3/committees/hs/reports-10/her10--05-vol2.htm. Accessed February 25, 2014.

- 56.Mason J. Qualitative Researching. 2nd ed. London, England: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dixon A; Salvation Army. Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill [written evidence]. http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/s3/committees/hs/inquiries/AlcoholBill/documents/126SalvationArmy.pdf. January 20, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014.

- 58.Davison C, Murie A, Perron M. Canadian Centre for Substance Abuse—NASAC. Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill [written evidence]. http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/s3/committees/hs/papers-10/hep10-10.pdf. January 20, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014.

- 59.Grant G. British Medical Association Scotland. Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill [written evidence]. http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/s3/committees/hs/inquiries/AlcoholBill/documents/021BritishMedicalAssociationScotland.pdf January 20, 2009. Accessed February 14, 2014.

- 60.Law J. Alcohol Focus Scotland. Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill [written evidence]. http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/s3/committees/hs/inquiries/AlcoholBill/documents/011AlcoholFocusScotland.pdf. January 20, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014.

- 61.Maryon-Davis A. Faculty of Public Health. Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill [written evidence]. http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/s3/committees/hs/inquiries/AlcoholBill/documents/050FacultyofPublicHealth.pdf. January 20, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014.

- 62.Nowak G. YouthLink Scotland. Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill [written evidence]. http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/s3/committees/hs/inquiries/AlcoholBill/documents/170YouthLinkScotland.pdf. January 20, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014.

- 63.Sher J. Children in Scotland. Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill [written evidence]. http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/s3/committees/hs/inquiries/AlcoholBill/documents/030ChildreninScotland.pdf. January 20, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014.

- 64.Stockwell T. Centre for Addictions Research of British Columbia. Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill [written evidence]. http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/s3/committees/hs/papers-10/hep10--10.pdf. January 13, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014.

- 65.Scottish Health Action on Alcohol Problems. Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill [written evidence]. http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/s3/committees/hs/inquiries/AlcoholBill/documents/138ScottishHealthActiononAlcoholProblemsSHAAP.pdf. January 20, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014.

- 66.SHAAP. Scottish Health Action on Alcohol Problems—Limiting the Damage of Cheap Alcohol. Edinburgh, Scotland: University of Sheffield; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ewing T. Association of Chief Police Officers in Scotland. Alcohol (Minimum Pricing) (Scotland) Bill [written evidence]. http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/S4_HealthandSportCommittee/Inquiries/Association_of_Chief_Police_Officers_in_Scotland.pdf. Accessed February 14, 2014.

- 68.Anderson P. Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill [response to questions from the Health and Sport Committee]. http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/s3/committees/hs/inquiries/AlcoholBill/documents/20100322ResponsefromDrPeterAnderson.pdf. March 22, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014.

- 69.Hardie W. Alcohol—Our Favourite Drug: From Chemistry to Culture. Edinburgh, Scotland: SHAAP: Royal Society of Edinburgh; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ritson B, Brunt P, Douglas N, Rice P, Keighley B, Frame E. Scottish Health Action on Alcohol Problems. Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill [supplementary evidence]. http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/s3/committees/hs/inquiries/AlcoholBill/documents/5Marce2010SHAPPSupplementaryEvidence.pdf. March 5, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014.

- 71.Ritson B. Scottish Health Action on Alcohol Problems (SHAAP)—Impact of Minimum Alcohol Pricing on Low Income Groups. Edinburgh, Scotland: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Collins A. SAMH (Scottish Association for Mental Health). Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill [written evidence]. http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/s3/committees/hs/inquiries/AlcoholBill/documents/127SAMHScottishAssocationforMentalHealth.pdf. January 20, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014.

- 73.Sturgeon N. Edinburgh, Scotland: Scottish Parliament; 2010. Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill—Stage 1. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Scottish Government. Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill: Supplementary Written Financial Information Using the Revised Sheffield Report (April 2010). Edinburgh, Scotland; 2010.

- 75.Meikle D. Scotch Whisky Association. Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill [written evidence]. http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/s3/committees/hs/inquiries/AlcoholBill/documents/128ScotchWhiskyAssociation.pdf. January 20, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014.

- 76.Paterson D. ASDA. Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill [written evidence]. http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/s3/committees/hs/inquiries/AlcoholBill/documents/015ASDA.pdf. January 20, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014.

- 77.Poley D. Portman Group. Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill [written evidence]. http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/s3/committees/hs/inquiries/AlcoholBill/documents/110ThePortmanGroup.pdf. January 20, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014.

- 78.Ford P. Liquor Control Board of Ontario. Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill [written evidence]. http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/s3/committees/hs/papers-10/hep10-10.pdf. January 19, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014.

- 79.Beard J. Whyte and Mackay Ltd. Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill [written evidence]. http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/s3/committees/hs/inquiries/AlcoholBill/documents/167WhyteandMackay.pdf. March 10, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014.

- 80.Browne P. Scottish Beer and Pub Association. Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill [written evidence]. http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/s3/committees/hs/inquiries/AlcoholBill/documents/133ScottishBeerandPubAssociation.pdf. January 19, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014.

- 81.Clark J. Sainsbury's plc. Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill [written evidence]. http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/s3/committees/hs/inquiries/AlcoholBill/documents/125Sainsburys.pdf. January 19, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014.

- 82.Verlik K. Alberta Gaming and Liquor Commission. Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill [written evidence]. http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/s3/committees/hs/papers-10/hep10-10.pdf. January 19, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014.

- 83.Klas K. Alcohol and Gaming Commission of Ontario. Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill [written evidence]. http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/s3/committees/hs/papers-10/hep10-10.pdf. March 18, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014.

- 84.Mackie K. Scottish Grocers’ Federation. Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill [written evidence]. http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/s3/committees/hs/inquiries/AlcoholBill/documents/137ScottishGrocersFederationLtd.pdf. January 20, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014.

- 85.McNeill J. The Co-operative Group Ltd. Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill [written evidence]. http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/s3/committees/hs/inquiries/AlcoholBill/documents/171TheCo-operativeGroupLtd.pdf. March 8, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014.

- 86.Price B. National Association of Cider Makers (NACM). Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill [written evidence]. http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/s3/committees/hs/inquiries/AlcoholBill/documents/081NationalAssociationofCiderMakersNACM.pdf. January 19, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014.

- 87.Taylor R. Morrisons. Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill [written evidence]. http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/s3/committees/hs/inquiries/AlcoholBill/documents/078Morrisons.pdf. January 19, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014.

- 88.Faris I. Brewers Association of Canada. Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill [written evidence]. http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/s3/committees/hs/papers-10/hep10--10.pdf. January 20, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014.

- 89.Lees M. Tennent Caledonian Breweries. Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill [written evidence]. http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/s3/committees/hs/inquiries/AlcoholBill/documents/172TennentCaledonianBreweries.pdf. January 24, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014.

- 90.Wilson S. Molson Coors UK. Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill [written evidence]. http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/s3/committees/hs/papers-10/hep10--10.pdf. January 19, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014.

- 91.Clark F. Society of Independent Brewers (SIBA). Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill [written evidence]. http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/s3/committees/hs/inquiries/AlcoholBill/documents/173SocietyofIndependentBrewersSIBA.pdf. February 26, 2010. Access February 14, 2014.

- 92.Smith P. Noctis. Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill [written evidence]. http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/s3/committees/hs/inquiries/AlcoholBill/documents/100NOCTIS.pdf. January 20, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014.

- 93.Macdonald L. Consumer Focus Scotland. Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill [written evidence]. http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/s3/committees/hs/inquiries/AlcoholBill/documents/039ConsumerFocusScotland.pdf. January 20, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014.

- 94.Brand K. Office of Fair Trading (OFT). Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill [written evidence]. http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/s3/committees/hs/inquiries/AlcoholBill/documents/105OfficeofFairTrading.pdf. January 20, 2010. Accessed February 14, 2014.

- 95.Wilkinson CA. Scottish Licensed Trade Association. Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill [written evidence]. http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/s3/committees/hs/inquiries/AlcoholBill/documents/139ScottishLicensedTradeAssociation.pdf. January 20, 2009. Accessed February 14, 2014.

- 96.Babor T, Caetano R, Casswell S, et al. Alcohol: No Ordinary Commodity: Research and Public Policy. 2nd ed. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Russell J, Greenhalgh T, Byrne E, McDonnell J. Recognizing rhetoric in health care policy analysis. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy. 2008;13(1):40–46. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2007.006029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Scottish Government. Changing Scotland's Relationship with Alcohol: A Framework for Action. Edinburgh, Scotland: Scottish Government; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Jenkin GL, Signal L, Thomson G. Framing obesity: the framing contest between industry and public health at the New Zealand inquiry into obesity. Obes Rev. 2011;12(12):1022–1030. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Parkhurst JO. Framing, ideology and evidence: Uganda's HIV success and the development of PEPFAR's “ABC” policy for HIV prevention. Evid Policy. 2012;8(1):17–36. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Shelley J. Addressing the policy cacophony does not require more evidence: an argument for reframing obesity as caloric overconsumption. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):1042. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Room R. Negotiating the place of alcohol in public health: the arguments at the interface. Addiction. 2005;100(10):1396–1397. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Smith KE, Katikireddi SV. A glossary of theories for understanding policymaking. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2013;67:198–202. doi: 10.1136/jech-2012-200990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kingdon JW. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies. Harlow, England: Longman; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Cairney P. Using devolution to set the agenda? Venue shift and the smoking ban in Scotland. Br J Politics & Int Relations. 2007;9(1):73–89. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Smith K, Hellowell M. Beyond rhetorical differences: a cohesive account of post-devolution developments in UK health policy. Soc Policy & Adm. 2012;46(2):178–198. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kansagra SM, Farley TA. Public health research: lost in translation or speaking the wrong language. Am. J. Public Health. 2011;101(12):2203–2206. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Katikireddi SV, Bond L, Hilton S. Perspectives on econometric modelling to inform policy: a UK qualitative case study of minimum unit pricing of alcohol [published online December 23, 2013] Eur J Public Health. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckt206. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckt206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hawkins B, Holden C, McCambridge J. Alcohol industry influence on UK alcohol policy: a new research agenda for public health. Critical Public Health. 2012;22(3):297–305. doi: 10.1080/09581596.2012.658027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.McCambridge J, Hawkins B, Holden C. Industry use of evidence to influence alcohol policy: a case study of submissions to the 2008 Scottish government consultation. PLoS Med. 2013;10(4):e1001431. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Gornall Jonathan. Under the influence: Scotland's battle over alcohol pricing. BMJ. 2014;348:g1274. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wood K, Patterson C, Katikireddi SV, Hilton S. Harms to “others” from alcohol consumption in the minimum unit pricing policy debate: a qualitative content analysis of UK newspapers (2005–12) Addiction. doi: 10.1111/add.12427. [published online January 8, 2014]. doi: 10.1111/add.12427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hilton S, Wood K, Patterson C, Katikireddi SV. Implications for alcohol minimum unit pricing advocacy: what can we learn for public health from UK newsprint coverage of key claim-makers in the policy debate. Soc Sci Med. 2014;102:157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.11.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Currie LM, Clancy L. The road to smoke-free legislation in Ireland. Addiction. 2011;106(1):15–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Online Appendix