Abstract

Context

In the past 50 years, individual patient involvement at the clinical consultation level has received considerable attention. More recently, patients and the public have increasingly been involved in collective decisions concerning the improvement of health care and policymaking. However, rigorous evaluation guiding the development and implementation of effective public involvement interventions is lacking. This article describes those key ingredients likely to affect public members’ ability to deliberate productively with professionals and influence collective health care choices.

Method

We conducted a trial process evaluation of public involvement in setting priorities for health care improvement. In all, 172 participants (including 83 patients and public members and 89 professionals) from 6 Health and Social Services Centers in Canada participated in the trial. We videorecorded 14 one-day meetings, and 2 nonparticipant observers took structured notes. Using qualitative analysis, we show how public members influenced health care improvement priorities.

Findings

Legitimacy, credibility, and power explain the variations in the public members’ influence. Their credibility was supported by their personal experience as patients and caregivers, the provision of a structured preparation meeting, and access to population-based data from their community. Legitimacy was fostered by the recruitment of a balanced group of participants and by the public members’ opportunities to draw from one another's experience. The combination of small-group deliberations, wider public consultation, and a moderation style focused on effective group process helped level out the power differences between professionals and the public. The engagement of key stakeholders in the intervention design and implementation helped build policy support for public involvement.

Conclusions

A number of interacting active ingredients structure and foster the public's legitimacy, credibility, and power. By paying greater attention to them, policymakers could develop and implement more effective public involvement interventions.

Keywords: patient participation, quality of health care, policymaking, qualitative research

In the past 50 years, patient involvement at the individual clinical consultation level has received considerable attention through the development of patient-centered medicine, self-care, and shared decision making.1–6 The growing epidemic of chronic diseases has also led to the recognition that because patients make day-to-day decisions about the management of their own health, they can be active partners in their clinical care as well.7 More recently, policymakers have become increasingly interested in extending patient-professional partnership to collective decisions about health care improvement and policymaking.8 For example, patient and public involvement is increasingly considered an essential component of quality assessment and reporting, priority setting, clinical practice guideline development and implementation, health technology assessment, comparative effectiveness research, and health governance.9–20

Beyond theoretical models and recommendations, however, we have little guidance based on evaluative research regarding how patients and the public can be effectively involved in health decisions at the population level. As a result, policymakers who wish to encourage the involvement of patients and the public face considerable challenges. First is the concern about recruiting participants who are representative of “ordinary” patients and members of the public, particularly those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds.21,22 A second problem is that participants may not understand the available scientific literature or may be unaware of clinical and resource implications. The actual influence that patients and the public can have on group decision making also is uncertain. Many critics thus have argued that public involvement, despite claims of its benefits, often is merely lip service. Indeed, a number of systematic reviews have documented the absence of trials of public involvement at the population level.5,17,23–26

Consequently, even though health care organizations are increasingly required to involve patients and the public in key aspects of their operations, few evaluation studies shed light on “what works” in involvement interventions.26–29 Based on their extensive review of the available evidence, Abelson and colleagues noted that the “literature is still mainly characterized by a combination of practice stories that are heavy on contextual learning but light on causal mechanisms, and experimental studies that are implemented in a theoretical vacuum.”29 To correct this, the authors recommended (1) defining public participation mechanisms more consistently, (2) linking empirical research with theory and prespecified hypothesis, (3) using multidisciplinary perspectives and mixed evaluation methods, and (4) conducting research on real-world involvement interventions.30 A process evaluation of experimental studies offers an appropriate study design to address these research gaps, showing why a particular public involvement intervention may or may not prove effective, by focusing on its internal dynamics and actual operations.31,32

We recently conducted the first trial of public involvement in collective health care decisions at the population level.33 This trial compared priority setting with and without public involvement. Public involvement resulted in mutual influence and greater agreement between professionals and members of the public, yielding health care improvement priorities that were better aligned with public expectations. In this article, we use the process evaluation data gathered from our trial to clarify why and how a number of “key ingredients” contributed to the effectiveness of the public intervention by enabling and constraining public members’ ability to influence collective health care decisions. By reporting the findings of a trial process evaluation, we hope to provide actionable guidance for policymakers responsible for designing and implementing public involvement interventions.

Our focus is on public involvement in “collective” decisions regarding health care improvement and policymaking, as opposed to individual patient involvement in clinical decision making.8 We use the term “public” to refer to patients, caregivers, and other community members affected by health care services and policies, and we use “professionals” to refer to clinicians and health care managers. In this article, “effective” public involvement is understood as the degree of public influence on collective decisions. Readers should keep in mind that other, equally valid, criteria could be used to assess the effectiveness of a public involvement intervention.34,35

The first section of this article is an overview of the theoretical literature that informed our trial. We next describe how, in practice, professionals and members of the public interacted and engaged in the involvement intervention, using empirical material collected from our trial's process evaluation (eg, videorecordings and direct observation). This qualitative analysis focuses on key components of the intervention, explaining variations in effects. In other words, this process evaluation seeks to better understand the dynamic relationships between the intervention components and public members’ ability to influence collective health care improvement decisions. Finally, the discussion section reflects on how policymakers can develop and implement more effective public involvement interventions.

Theoretical Assumptions Underpinning Public Involvement Interventions

Existing theories of public involvement embody certain assumptions and hypotheses about what public involvement interventions are “made of” (their principal components) and “how they are expected to work” (their internal dynamic explaining outcomes).36–40 Three main theoretical constructs have been proposed to explain the public's influence on collective health care decisions: (1) public members’ credibility and ability to contribute knowledge that is considered valid and relevant to inform collective health care decisions, (2) their legitimacy to speak on behalf of people affected directly or indirectly by health care services and policies, and (3) their power and ability to influence collective health care choices.21

Technocratic theories of public involvement stress the importance of the public's ability to demonstrate credible expertise. Rowe and Frewer contend that information sharing is the core process underlying public involvement and classify interventions according to the flow of information between professionals and the public: communication methods (in which information is communicated to the public), consultation (information is collected from the public), and participation (information is exchanged between professionals and the public).41 Such an “information flow” perspective is particularly well developed in deliberative theories, which anchor public involvement around the careful weighing of reasons for and against collective action propositions.42 The core hypothesis of deliberative theories is that the exchange of reasonable and credible arguments should result in mutual learning and in the generation of solutions that can be rationally justified to those affected by it.43–46 From this perspective, access to the best available evidence through training and preparation is a critical component of effective public involvement interventions, ensuring that valid and relevant information is collected and exchanged among competent participants.35,41

Collins and Evans contend that members of the general public are “experience-based experts” whose knowledge is based mainly on their personal experiences rather than on their degrees and professional qualifications.47 These authors further distinguish among 3 levels of public expertise. At the most basic level, public members have no expertise at all in a specific domain and are unable to understand professionals. At the highest level, some public members have developed contributory expertise in a specific domain, meaning that they can contribute new knowledge to a specific aspect of collective health care decisions (eg, as a chronic disease patient with long-term experience of a given health condition). At the intermediate level of interactional expertise, public members have developed knowledge that allows them to interact meaningfully with professionals. Interactional expertise is assumed to be particularly important when professionals and the public deliberate, enabling both parties to understand how their respective expertise can contribute to collective health care decisions. This distinction between interactional and contributory expertise challenges sponsors of public involvement to clarify what specific knowledge and experience public members are expected to contribute to collective decisions and what forms of expertise professionals and the public must have in order to interact meaningfully with each other.

Democratic theories emphasize the importance of the public's legitimacy to speak on behalf of others; indeed, it is seen as a critical component of effective public involvement.27,45,48–51 Judging the public members’ legitimacy requires paying close attention to the social practice of public involvement and the political and organizational context in which “divergent notions of representativeness are deployed in pursuit of differing roles for public participation.”48 Observations of real-life involvement interventions suggest that professionals use different criteria to support (or question) the public's legitimacy, such as the participants’ statistical representativeness, the use of formal public representatives’ selection and nomination procedures, and the participants’ accountability to the community members they represent.48,49,51

Finally, a number of authors have highlighted the importance of power as a core ingredient for explaining the public's relative influence on collective decision making. Power may be exercised over who is allowed or not allowed to participate in collective decision making, as well as what kinds of arguments and propositions are regarded as receivable or not.52 Deliberation theory emphasizes the importance of balancing the participants’ power differences in order to agree on the “best” rational arguments, open to all competent speakers and free of coercion or manipulation.44,53 But observations of actual deliberation processes suggest that these egalitarian ideals may not always operate in practice. For example, research on small-group decision making suggests that collective decisions often tend to move toward the majority's view.53,54 In the context of collective health care improvement and policy decisions, power may also be determined by professional and hierarchical status.27,48 In its more subtle and discursive forms, power may be exerted through the types of assumptions that are taken for granted and accepted by the group.45 Finally, power struggles can be woven into the fabric of a public involvement intervention itself, shaping the selected method of involvement, who is asked to participate, and how its sponsors define “effectiveness.”55 While power is closely connected to and contingent on the public's credibility and legitimacy, it also points to other important components of public involvement interventions, including control over agenda and procedures, and decisions about how public recommendations will be incorporated in actual policy decisions.56

In summary, the theoretical literature points to the need to look closely at how public involvement interventions frame and foster public members' legitimacy, credibility, and power, in order to explain their ability to influence collective decisions. The literature suggests that process attributes of involvement interventions (eg, their principal components and internal dynamics) are likely to affect outcomes differentially. This requires clarifying for whom public representatives are speaking and the specific expertise they are expected to contribute to collective decision making. By looking at what happens when members of the public interact with professionals, and by mobilizing a theory-informed understanding of the key processes at play, this article seeks to understand the involvement process informing the development of more effective interventions.

Methods

We conducted a qualitative process evaluation of a public involvement trial (see Box 1). Details of the development and testing of the public involvement intervention have been published elsewhere.33,57 In a nutshell, we randomized Health and Social Services Centers in a Canadian health region in intervention and control sites. Individual participants included members of the public (chronic disease patients, caregivers, and healthy adults) and professionals (clinicians and managers). We asked the participants to select health care improvement priorities from a list of 37 validated quality indicators for chronic disease prevention and management in primary care. In the intervention sites, the public members (1) attended a 1-day preparation meeting, (2) were consulted by vote on their local priorities for improvement, and (3) participated in a 2-day meeting to deliberate with professionals and reach agreement with them on local health care improvement priorities. The 2-day meeting between public members and professionals included small-group deliberation, feedback of the public consultation results, and voting. In the control sites, the professionals among themselves prioritized quality indicators without public involvement (no participation of public members or feedback about the public consultation).

Box 1. Trial Overview.

Design: Cluster randomized trial.

Context: Health and Social Services Centers in a Canadian region (n = 6) were required to select health care improvement priorities to be incorporated in their financial accountability contract with the regional health authority. Health and Social Services Centers could choose from a list of 37 validated quality indicators for chronic disease prevention and management in primary care (including indicators on access, integration of services, technical quality of care, quality of interpersonal relationships, and health outcomes).

Baseline public priorities: Public members (n = 83), including chronic disease patients, caregivers, and healthy adults, were recruited from all participating sites. All public members participated in a 1-day preparation meeting and were consulted by vote on their local priorities for improvement.

Randomization: Health and Social Services Centers were randomized in intervention (n = 3) and control sites (n = 3) to compare health care improvement priority setting with and without public involvement.

Intervention: Health care improvement priorities were selected by both professionals and public members. Professionals received feedback about the public consultation and deliberated with public representatives in a face-to-face meeting.

Control: Health care improvement priorities were selected by professionals only, without public involvement. Professionals did not receive feedback about the public consultation and deliberated among themselves, without public representatives.

Participants: In all, 172 individuals from 6 Health and Social Services Centers participated in the study. Public representatives (n = 83) included chronic disease patients (81%), caregivers, and healthy adults. Forty-seven percent had a primary or high-school education; 56% had an annual household income of less than US$40,000; and 23% had been hospitalized during the previous year. Professionals (n = 89) included managers (35%), physicians (13%), nurses (24%), and allied health professionals (28%).

-

Results:

Priorities selected in intervention sites placed more emphasis on access to primary care, self-care support, patients’ participation in clinical decisions, and partnership with community organizations (p < 0.01).

Agreement between public representatives' and professionals’ improvement priorities increased by 41% in favor of intervention sites (95% CI +12, +58%, p < 0.01). The intervention fostered mutual influence between patients and professionals priorities. Professionals’ choices moved toward indicators prioritized by the public (eg, access), and public representatives’ choices moved toward indicators prioritized by professionals (eg, self-care support).

Participants' perception of the quality of the deliberation process scored high in all domains (quality of the information received, procedures and moderation, interaction among participants, and overall satisfaction).

There was no significant difference in professionals’ intentions to use the selected quality indicators for health care improvement, which scored high in both intervention and control groups.

At the end of the trial, the priorities established with public involvement were significantly different from those selected by the professionals alone. The intervention fostered mutual influence between professionals and members of the public. We observed variations in the effects of public involvement across intervention sites, topic areas, and after the introduction of different components of the intervention. For example, the public's ability to influence the professionals was more pronounced for some dimensions of quality, like access to primary care (see Table 1). The public's influence also was greater when public participation in small-group deliberation was combined with feedback from public consultation (see Table 2).

Table 1.

Changes in Professionals’ Priorities During the Involvement Intervention

| Public Members' Top 3 Priorities | Professionals' Priorities | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Quality Indicator | Rank | Baseline Rank | Final Rank |

| Family physicians accepting new patients | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Perceived difficulty to obtain an appointment with a primary care professional | 2 | 13 | 4 |

| Respect and empathy | 3 | 16 | 18 |

Changes in professionals' priorities during the involvement intervention, in relation to public members’ top 3 priorities (Rank 1 = priority selected by the highest proportion of participants).

Table 2.

Agreement Between Professionals and the Public at Different Stages of the Intervention

| Baseline | After Public Participation | After Public Participation and Consultation Feedback | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Professionals’ agreement with public members’ baseline priorities | 0.273 | 0.322 | 0.356 |

| Public members’ agreement with professionals’ baseline priorities | 0.273 | 0.323 | 0.498 |

| Mutual agreement between public members’ and professionals’ priorities | 0.273 | 0.615 | 0.688 |

Agreement between public representatives’ and professionals’ priorities at different stages of the intervention, calculated using Spearman's correlation coefficients (0 = no agreement, 1 = perfect agreement).

The trial's process evaluation sought to elucidate these different results by drawing from the qualitative data (direct observation and videorecording) collected during the trial. Davies and colleagues showed the value of combining videorecording and direct observations to explore both the content of the deliberations and the participants’ social interactions during a public involvement intervention.45 We videorecorded 14 one-day meetings, and 2 independent, nonparticipant observers used structured observation charts to describe the deliberation content, the types of arguments used, and the participants’ interactions. During all phases of the project, we took field notes to record informal interactions that were not captured on video. Structured debriefing sessions with the observers and moderators were held immediately after each meeting, during which key interactive moments were flagged and all observations were linked to the videotranscript using time codes to allow later validation against the original videorecording.

Our primary empirical materials were our observations and field notes, as well as a full verbatim transcription of videorecording from a sample meeting in each intervention site. The key moments flagged from all our meetings also were transcribed from the original recording. We analyzed all videos, seeking to complement direct observations. That is, we tried to identify varying degrees of public influence—among the different sites, over time, and across topic areas—to identify the components of the interventions that could help explain these variations. Given our applied policy research focus, we used framework analysis58 to chart all transcribed material and notes and to graphically map the main aspects of the public involvement process and their relationships to outcomes. The principal investigator (Antoine Boivin) attended all the meetings with a research assistant, transcribed the recordings, and conducted the initial analysis. The coprincipal investigator (Pascale Lehoux) attended some of the meetings and validated the initial analysis against the original transcript. We then discussed and refined our analysis with all members of the research team.

Our analysis was structured around the main public involvement intervention components, including (1) building a policy coalition supportive of public involvement, (2) public recruitment and training, (3) public participation in face-to-face deliberation with professionals, (4) group moderation, and (5) feedback from a wider public consultation. While some of these components were identified from our review of public involvement theory, others emerged inductively.

Results

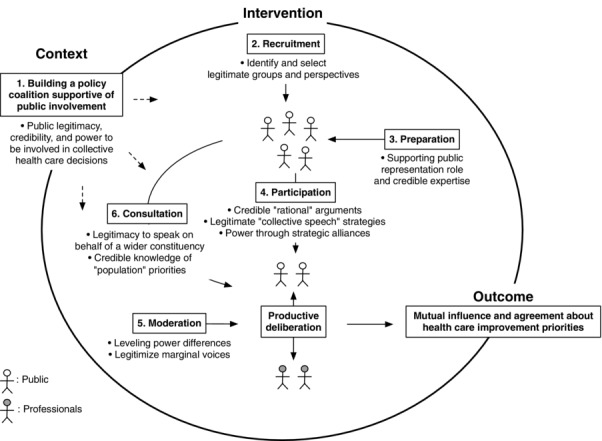

Figure 1 illustrates the 6 main components of the public involvement intervention and their relationship to outcomes. In the next section, we explore these components’ contribution to the public's influence on collective decisions.

Figure 1.

Key Components of a Public Involvement Intervention

Building a Policy Coalition Supportive of Public Involvement

During the design and pilot phase of the study, we consulted various stakeholders about the proposed public involvement intervention, including regional and Health and Social Services Center directors, medical leaders, as well as public representatives sitting on local and regional health authorities’ boards. While all stakeholder groups were supportive of public involvement, their endorsement was motivated by different reasons and was shaped by the surrounding organizational context. For example, the regional health authority directors saw public involvement as a lever for influencing the Health and Social Services Centers’ priorities and aligning these with “public needs.” In contrast, local chief executive officers (CEOs) saw public involvement as an opportunity to “educate” the public and legitimize their own organizations' priorities: “I think this will help the population to better understand our priorities and action” (manager, Site C). (Note that quotations are from the A, B, and C intervention sites and that pseudonyms are used throughout the text.) Clinicians and medical leaders saw the intervention as a way to promote patients’ responsibility for their own individual care: “It is winning to involve people in taking care of themselves, that is why it is important that they be present when big decisions are made” (clinician, Site B). Public members’ motivation to support and participate in the trial was either to improve local services or to learn about health and health care: “I am curious to see what we will learn”; “I want to bring my experience to improve services” (public, Site A).

Our tested intervention was therefore supported by a coalition of organizations and individuals with different expectations about the actual goals of public involvement. These competing expectations created tensions as the intervention was implemented in practice and the abstract idea of “public involvement” became more concrete. These tensions revolved around the degree of legitimacy and credibility of public involvement, as well as the actual power that should be delegated to public representatives in the collective decision process. For example, as the group's task became clearer, public members questioned how they were expected to contribute to health care priority setting and what rules would be put in place to address power imbalances: “[I'm wondering,] not in a pejorative sense, but with the level of the debate, will the population's comments have a similar weight than those of a chief executive officer?” (public, Site A).

Public members also questioned the credibility of their contribution in certain aspects of their task and negotiated the boundaries of their role to ensure its coherence with their specific expertise. For example, in the pilot phase of the project, public members were asked to rate the feasibility of using each quality indicator in clinical practice, a task they did not feel sufficiently prepared to carry out. Accordingly, the definition of the public's task was restricted to rating the perceived importance of each quality indicator for improved patient care.

These negotiations among stakeholders resulted in varying degrees of policy support for public involvement. Across the sites, the amount of public influence was related to the levels of support from professionals in positions of power, especially CEOs and medical leaders. For example, in Intervention Sites A and B, CEOs and medical leaders proactively sought advice from public members during deliberation meetings and promoted policies important to the public (eg, access to a family physician and a primary care professional). In Intervention Site C, the CEO sought to adopt a priority that was highly ranked by physicians (screening for high blood pressure), which limited the public impact on group choices.

Recruitment: Representing Legitimate Groups and Perspectives

Our recruitment strategy was to identify members of the public who would be considered legitimate in the eyes of local professionals and members of the public. We thus delegated the identification of potential candidates to local recruitment teams composed of a senior manager, a physician, and a patient representative sitting on the Health and Social Services Centers’ users committee. We assumed that recruiting patients and caregivers with personal experiences of different health conditions and from various sociodemographic groups would further increase the public's legitimacy. A member of the research team selected members of the public from local lists of proposed candidates to ensure a balanced representation in age, gender, health, and socioeconomic status. This recruitment strategy proved effective in reaching public members from low socioeconomic groups and building a sample that was representative of both local patients with chronic disease and caregivers (Box 1). Interestingly, we observed later in the trial that professionals were more sensitive to the priorities expressed by people from their own local territory (although these were drawn from small samples of 12 to 15 public members) than from the pooled regional priorities collected from the total sample of 83 public members involved in the trial. This suggests that professionals’ judgments about public members’ legitimacy may be guided by the recruitment of people representing relevant (local) perspectives rather than by strict statistical representativeness criteria based on demographic characteristics.

We also observed that public members with previous experience of representation and group committee process (eg, as a board member, as a patient representative on committees, or through professional experience outside health care) were somewhat more influential than patients without such previous experience. It is worth pointing out that public members with a lower level of education were often equally or more influential than those with more education, possibly because deliberation with professionals involved group talk and the sharing of lived experiences, rather than abstract or written tasks.

Preparation: Supporting Public Representation Role and Expertise

The public representatives’ preparation day contributed to the intervention's impact by building the participants’ sense of credibility and their ability to contribute specific expertise to the prioritization task. The preparation meeting allowed the public representatives to ask questions of clarification in a nonthreatening environment and to build their confidence. This preparation put them in a favorable position when they later met with professionals: “I am part of those who had a warm-up!” (public, Site A). Public members also felt more competent to contribute to the group's task as they progressed through the intervention: “I knew the topic because we had a [preparation] day. This was really helpful. Without it, it would have been painful” (public, Site B).

The preparation day also contributed to the participants’ sense of legitimacy as public representatives, which was critical to their ability to later influence group decisions. As members of the public discussed their personal experiences as patients and caregivers during the training day, we observed a broadening of the participants’ perspectives and their growing sense of a collective “public representative” identity. One participant noted that hearing the experience of others made her more aware of the needs of different people in her community: “I have a family physician myself, but I have become more conscious of the difficulties for people who don't. In the end, I voted to help Paul and to help Clare [who do not have a physician]” (public, Site A).

These observations suggest that the participants’ progress in understanding their representation role, and also how their legitimacy and credibility evolved over time, was partly framed by how they were recruited and selected, their opportunity to interact with other public members, and their preparation.

Public Participation: Rational Deliberation, Collective Voices, and Strategic Alliances

The tested public involvement intervention included different involvement methods (public participation in small-group deliberation, public consultation through voting, and public communication of group decisions). These components were introduced sequentially, which allowed us to explore their respective impact on group decision making (Figure 1).

The participation component of the intervention (Days 1 and 2) was important to fostering mutual influence between the public and professionals. The public members’ influence was linked with (1) their ability to use “rational” and credible arguments in areas of deliberation in which they were considered experts, (2) their adoption of “collective speech strategies” that supported their representation role, and (3) through informal interactions favoring the establishment of alliances and coalitions among public members and professionals.

Our observation of small-group deliberation content revealed specific areas in which professionals saw public members as credible experts, which allowed them to contribute arguments perceived as “rational.” This included issues such as their personal experience of care, their expectations and needs, their perception of the public acceptability of health care innovations, as well as their knowledge of existing community organizations and services. Professionals actively sought validation from public members when they discussed issues like access to care or the quality of interpersonal relationships: “Our final group priority is ‘patient participation in clinical decision-making,’ where one of our health care users said a key sentence: ‘working in team with the patient.’ … Do user representatives around the table agree with all that?” (manager, Site B). In other areas of deliberation, such as the psychometric properties of the proposed quality indicators, the clinical value of different treatment options, and the resource implications of the proposed changes, public members increasingly displayed interactional expertise as they became more familiar with the issues, but the professionals essentially still made the authoritative contributions in these areas.

The public members increasingly endorsed a representation role as they deliberated with the professionals, not only drawing from their own individual experience but also voicing concerns raised by other participants. Their ability to refer back to experiences voiced by other public members in the preparation meeting supported the public representatives’ ability to legitimately claim that they spoke on behalf of a wider constituency. This collective perspective was also reflected in the way that the public members portrayed their own role. Although their ability to use personal stories and anecdotes was important to establish their position as “real patients,” those public members who brought only their own experience to the table were less effective in influencing professionals. For example, many public members originally identified themselves through their disease (eg, “I am John, and I have diabetes”) but later framed their role and contribution as “population,” “public,” or “patient representatives” (eg, “I am still speaking on behalf of the public”). The public members’ adoption of “collective speech” strategies—and their ability to support their claims of representing a larger constituency through concrete examples drawn from others’ experiences—thus contributed to their influence in the group deliberations.

Finally, the impact of the public participation component of the intervention also appeared to be mediated by informal social interactions between professionals and public members, which led to greater mutual understanding and helped lessen the power differential. We observed that informal interactions during breaks and lunch time supported this change in perspective: “We see that they are like us, fathers and mothers”; “When we hear health professionals through their union's representatives [on TV], it is not very positive and we gain from meeting them”; “I had some ideas, and by hearing others, my opinions have changed. [Interacting with these] professionals allowed us to see the other side of the coin because we are on one side, in the waiting room, and they are on the other side, waiting for us” (public, Site B). As a consequence of this face-to-face interaction, dissent rarely put professionals and the public into a “us versus them” position but instead led to shifting alliances among the participants. In Intervention Site A, for example, public representatives allied with managers and nurses to support their claim that access to a family physician was problematic in their community and should be prioritized. Similarly, in Intervention Site B, the CEO and the medical leader actively sought validation and support from public members to support their view that patients’ participation in clinical decision making should be prioritized.

The “weight of majority” was strongly at play during deliberation and supported this need for strategic alliances. Indicators that received only a few votes in the first round of voting tended to be marginalized in group deliberation unless their proponents could rally support from other influential group members. This may partly explain why indicators that generated wide consensus among public members (eg, access) were more influential than those identified by a minority (eg, respect and empathy) (Table 1). In some cases, alliances of professionals and public members resulted in compromises between both perspectives. In Intervention Site A, for example, the public participants’ insistence over access to a family physician (their top priority at baseline) was countered by the professionals’ belief that greater access could realistically be achieved only by investing in interdisciplinary teams (professionals’ top priority at baseline). Deliberation in this site led to the adoption of a “compromise indicator” on the difficulty of obtaining an appointment with a primary care professional, thereby bridging public members’ concerns over access and professionals’ insistence on supporting primary care teams.

In sum, direct public participation in deliberation meetings with professionals supported the public members’ influence on group decisions through their ability to display “rational” arguments, their use of “collective speech” strategies, and the establishment of strategic alliances with professionals. These were facilitated by informal social interactions with professionals and built on experience shared among public members during the preparation meeting.

Moderation: Leveling Power Differences and Legitimizing Marginal Voices

We hired an expert in communication as our lead moderator, who was assisted by 2 comoderators with formal training in health care (employees of the regional health authority). We observed that the lead moderator had less content expertise and was more focused on effective group processes, paying close attention to the setting and enforcing ground rules, supporting a relaxed atmosphere conducive to deliberation and compromise, and asking for frequent clarifications when technical language was used. The lead moderator also used a number of strategies to minimize power differences, by actively seeking public members’ opinions during discussions or by using seating plans (eg, not letting lead physicians sit with CEOs and seating public members in pairs).

The professionals’ and the public members’ expression of different perspectives did cost time and effort in reaching a consensus. We observed that debates were more dynamic and lively in those groups including public representatives but that group deliberation lasted, on average, 10% longer. The moderator therefore needed to keep the participants focused on the task (eg, “When you say that, what indicator are you arguing for?”), “closing” debates when acceptable compromises and consensus were emerging (eg, “OK, it seems that we will definitely keep this indicator”), and “storing away” persistent disagreements and unresolved issues (eg, “You clearly will need to discuss your action plan among yourselves”).

The participants’ tasks and ground rules presented at the beginning of each meeting emphasized the value of expressing different views, even though this was difficult for many participants. For instance, we observed a number of cases in which professionals would “lecture” public members about proper health-oriented behaviors (ie, tobacco cessation), which made it more difficult to voice concerns raised in the public-only preparation meeting, in which a number of public members criticized tobacco cessation programs.

During the deliberations, the moderators played a pivotal role in ensuring that the public members engaged in debates, by actively seeking their dissenting views:

Physician: I have a lot of difficulty with [the indicator measured from] the patients’ perceptions. Perceptions are not reality.”

Moderator: “So for you, this would not be a valid indicator. I would be interested to hear from someone who has the opposite opinion?”

Manager: “I disagree with Dr. Smith on the uselessness of patients’ perceptions. If we measure it as a general tendency, it is important.”

Public: “I agree with Dr. Smith. However, when we have a global statistic, it can help. Perceptions require us to dig deeper.” (Site C)

Moderation techniques that actively sought the expression of marginal voices (eg, “I would be interested to hear from someone with the opposite opinion”) encouraged the active involvement of public representatives by offering a safe opportunity to express dissent with powerful participants (“I agree with Dr. Smith. However, …”).

Whereas our lead moderator was good at facilitating the group process and the expression of divergent opinions, the 2 health professionals acting as comoderators tended to focus more on discussion content. These content-expert moderators sometimes fell into a participant role, arguing, for example, in favor of the robustness of certain indicators as a strategy to build consensus. As a result, we noticed that our lead moderator was somewhat more effective in supporting public participation, because of her focus on listening to and facilitating the group process rather than being distracted by or trying to contribute to the subject matter.

Public Consultation: Bringing the Population's View

Although public participation alone brought some change in the professionals’ priorities, we observed that it was somewhat ineffective in challenging more entrenched opinions (Table 2). Part of the public members’ continuing difficulty was legitimizing their claim of speaking on behalf of the wider population rather than relying on anecdotal personal experiences. These criticisms of public members’ “representativeness” became more pointed when disagreements with professionals could not be resolved. For instance, one manager argued that comments from “those people here [pointing at public members]” gave her little information about “what our population wants” (Site B).

Statistical feedback of the public consultation was introduced during the second day of deliberation. The public members’ baseline priorities collected at the beginning of the study were contrasted with those of the professionals, and descriptive statistics were presented for the overall region and for each local intervention site. The professionals saw the public consultation feedback as contributing to a better understanding of their “population needs,” and it played various roles in subsequent deliberations. First, it made more visible the gap between the professionals’ and the public members’ priorities. Second, it added weight to individual public members’ claims of representing a wider group of people and opened the door to exploring differences of opinion:

Public 1: “I will tell you frankly, I am surprised that there are 3 indicators on which we agreed and the rest … for me as a member of the public. …”

Public 2: “There are important things that have been left aside.” (Site C)

Third, because the public representatives who had been consulted at baseline were also present to discuss statistical findings with professionals, they could claim specific expertise in the interpretation of results. The public members’ participation in the intervention sites shaped in different ways the interpretation of the credibility of statistical summaries. In some instances, the public members kept their distance from the public consultation findings (“Self-care support, in reality, I participated in this consultation […] maybe we did not understand the question and did not put enough importance on this” [public, Site B]), while in other cases, their presence supported the credibility of the findings and ensured that they were not simply tossed aside by the professionals:

Public: “There is an enormous gap between public and professionals’ priorities.”

Moderator: “Do you think this is a [public] misunderstanding problem?”

Public: “Not at all. This would imply that you question the population's intellectual capacities [laughs].” (Site A)

Overall, the statistical feedback of the public consultation prompted the participants to negotiate further any differences of opinions. The intervention's public consultation component also added legitimacy and credibility to the public members’ role in setting priorities. More precisely, the combination of public consultation and direct public participation acted synergistically and increased the public members’ influence on the professionals. This synergy was particularly visible in Intervention Site A, where the introduction of the public consultation feedback altered the balance of power and shifted professionals’ opinions in favor of public priorities on access to a primary care professional.

Discussion

Key Findings and Contribution to the Existing Literature

As underscored at the beginning of this article, the current literature on public involvement suggests that issues of credibility and legitimacy are subject to ongoing negotiations among participants and stakeholders whose interests and power may be supported or challenged by public involvement.19,45,48–50,59 As our process evaluation findings illustrate, exploring these tensions requires opening the “black box” of public involvement to understand why and how certain components can address the imbalance of power and expertise. Results from this study unpack some of the “key ingredients” that structured and supported productive deliberations between members of the public and professionals. Our findings point at how specific components of involvement interventions foster public members’ legitimacy, credibility, and power to influence health care improvement and policy decisions (Figure 1).

One contribution of our study is showing how both technocratic (public credibility) and democratic process issues (their legitimacy to represent others) underlie the unfolding of a public involvement intervention and shape its impact on collective decisions. In the literature, technocratic discussions about public expertise largely focus on the notion of technical competence and assume that “lay” members of the public do not always understand “scientifically valid” evidence.60,61 Our findings point more specifically toward the importance of credibility as a condition for successful involvement, that is, the perception that professionals and public members have of their respective expertise in important areas of deliberation. This means that public involvement interventions not only must give public participants enough information to understand the technical language used by professionals but also must support their ability to become a credible source of knowledge for professionals. It is interesting to observe empirically that such public expertise comes partly from individual (shared) experiences and partly from the public's ability to access population-based data. In our study, the recruitment of patients and caregivers with direct personal experience of chronic disease, as well as the opportunity provided to broaden their knowledge base by interacting with other community members helped develop a specific public expertise.47 As they became more solidly grounded in their roles, both the public members and the professionals also became more aware of the limits of their own expertise and actively engaged in a process of mutual learning and influence, as postulated by deliberation theory.46,53,56,62–65

From a democratic perspective, our findings point toward the need to better distinguish the statistical representativeness of a group from the representation role of individual participants.26,51 Statistical representativeness—the correspondence between the descriptive characteristics of a sample and those of the population from which they are drawn—is only one aspect of public members’ legitimacy and is most applicable to public consultation strategies in which large groups of participants can be recruited. In contrast, the logic of direct public participation in small-group decision making is mainly one of representation, in which individual participants are asked to speak for a wider constituency. Our findings highlight the need to reframe the debate about the recruitment of “real patients” or “ordinary citizens” and instead explore how public involvement interventions can support public members’ legitimacy to represent others, in both their own eyes and those of health professionals.21,66 In our study, a balanced recruitment strategy and the use of a preparation meeting supported participants' ability to legitimately represent their community.

Finally, our findings suggest that different components of public involvement interventions can modulate the power imbalance between professionals and the public. Process-oriented group moderation can play an important role in this regard through strategies like seating plans, the establishment of ground rules with participants, and agenda setting. The degree of power over collective health care decisions also is contingent on ongoing negotiations among stakeholders on how the public will be involved and supported in practice. Our observations also confirm findings from other studies suggesting that there is “strength in numbers,” meaning that public power can be mediated by the number of public members (through their impact in voting), their ability to build strategic alliances with other group members, and the possibility of supporting their claims based on population surveys and public consultation.45,55,59

Policy Implications

Observations from our study indicate that restricting the public's involvement to offering “a seat at the table” to one or two individuals without appropriate support is unlikely to change health care and policy decisions. Indeed, many of the key ingredients identified in this study appear to be absent from existing public involvement programs.25 Accordingly, a number of our study's actionable policy implications can be used to increase the potential effectiveness of public involvement.

First, questions about the design of public involvement interventions are often reduced to identifying the “right” participants who seem competent to understand the conversation while still being seen as representative of “ordinary” patients or “lay” public members. As a result, more emphasis is put on recruitment and sampling strategies and less on other intervention components, such as who identifies public members, what opportunities they have to interact with one another, and how they can access population-based evidence. Our results also point to the importance of preparation meetings that go beyond a basic understanding of technical terms and encourage the development of a specific public expertise.

An important observation from our trial is the synergy of the preparation, participation, and consultation components of the intervention, each contributing to the public's credibility, legitimacy, and power. In the academic literature, a theoretical divide tends to separate proponents of participation methods (based on deliberative theory and political sciences), consultation methods (based on epidemiological methods and health economics), and communication methods (focused on risk communication, behavioral change theories, and clinical decision making). This academic fragmentation has so far supported a piecemeal approach to the development of public involvement interventions that may have hampered their practical effectiveness. Our findings provide more comprehensive guidance for policymakers who wish to develop and implement public involvement interventions that integrate consultation, participation, and communication methods.

Collective health care decision-making processes like guideline development, health technology assessment, and clinical priority setting are often chaired by content experts and people in a hierarchical position of power (eg, lead clinician and CEO).25 Our findings show that group moderation by an expert in group processes (rather than by a content expert) could help even out existing power differences, facilitate more fruitful deliberation, and support professionals’ and public members’ mutual understanding and influence.

As we observed in this article, the goals and actual process of involvement were subject to ongoing negotiations throughout the design and implementation of the intervention. During the study's pilot phase, such negotiations were arbitrated by the research team, who ultimately decided on the format of the public involvement intervention tested in the trial. We speculate that more naturalistic involvement interventions might have tipped the negotiations in another direction and resulted in rules of engagement that may not have been favorable to public influence on collective choices. Some settings also may simply be too polarized to agree on public involvement procedures. Because the rhetoric of public involvement commands such widespread support, it may be tempting to gloss over the tensions regarding the competing goals and roles that the public members are expected to play. However, without negotiating and building policy support for public involvement, the search for effective involvement interventions will likely remain elusive. Consequently, policymakers should seek to apply broad but clear and consistent principles enabling the development of more effective involvement interventions.

Strengths and Limitations of Our Study

The strength of this study is the detailed process evaluation data collected from a real-world experimental study. Informed by theory, our evaluation of an intervention in which both productive disagreements and mutual learning took place offers a concrete example of integrating quantitative outcome results and qualitative process analysis. This methodological approach reveals the ingredients that hold together public involvement interventions and help them succeed.

The generalizability of our findings could be limited because of the diversity of public involvement interventions and the influence of the sociopolitical contexts in which they are implemented. But by separating the process analysis of our intervention into its different components, we can more easily assess the generalizability of our findings to similar public involvement interventions.31

Our study focused on the influence of components “inside” a public involvement intervention rather than on the role of “external” contextual factors (eg, health care organizations characteristics, types of policy decisions, and community characteristics). Research on contextual factors affecting the effectiveness of public involvement interventions is still in its infancy, and experts in the field have called for stronger evidence about “what works in which context.”67,68 Our findings point to the limits of public involvement interventions alone and to the importance of external factors shaping public members’ credibility, legitimacy, and influence on collective health care decisions. For example, quality indicators measured from the patient's perspective (eg, respect and empathy) were difficult for the public members to promote, partly because less research has been conducted on quality indicators measured from patients’ experience, as opposed to technical, disease-specific indicators like blood pressure control. Research decisions made before the involvement intervention could therefore have affected the credibility of public priorities and their ability to influence professionals. This suggests that the impact of public involvement is shaped not only by the involvement intervention itself but also by contextual factors outside the participants’ and sponsors’ control. Studying those contextual factors is an important direction for future research.

Finally, seeking the active ingredients of public involvement, rather than simply describing how the intervention is unfolding in practice, implies certain normative judgments about the desirable outcomes of public involvement interventions. In our study, we assumed that interventions supporting the public members’ influence on collective decisions could be considered “effective.” We, however, recognize that other normative models of what constitutes effective involvement exist (eg, considering public involvement as an intrinsic good, independently of its impact on collective decisions) and could have resulted in different interpretations.55

Conclusion

Public involvement calls for well-thought-out interventions that incorporate a number of interacting active ingredients. In this study, the public members’ credibility, legitimacy, and power increased their ability to influence group decisions. This was framed and strengthened by the recruitment of a balanced group of participants, structured training, opportunities to draw from others’ experiences, moderation techniques focused on effective group processes, and the combination of broad public consultation with public participation in small-group deliberation. The engagement of key stakeholders in negotiating the design and implementation of the intervention helped build policy support for public involvement. We need to better distinguish statistical representativeness from representation roles in discussions about public legitimacy. We also must expand our notion of public members’ competence beyond their understanding of technical terms in order to support the development of a contributory public expertise. Greater attention to these ingredients could lead to more effective public involvement interventions and increase public members’ influence on health care improvement and policy decisions.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by an operating grant from the Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement and the Agence de la Santé et des Services Sociaux de l’Abitibi-Témiscamingue (CHS-2160). Antoine Boivin is supported by a Clinician-Scientist Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and Pascale Lehoux holds the Canada Research Chair on Innovation in Health. The study was approved by the Université du Québec en Abitibi-Témiscamingue ethics committee (Rouyn-Noranda, Quebec, Canada). Jolyne Lalonde, Celine Hubert, and Suzanne Chartier helped plan the intervention and data collection.

We would like to thank the editor and 2 anonymous reviewers for their careful evaluation of our manuscript and for providing helpful criticism and suggestions.

References

- 1.Balint M. The Doctor, His Patient and the Illness. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196(4286):129–136. doi: 10.1126/science.847460. May 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stewart RE, Vroegop S, Kamps GB, van der Werf GT, Meyboom-de Jong B. Factors influencing adherence to guidelines in general practice. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2003;19(3):546–554. doi: 10.1017/s0266462303000497. Summer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA. 2002;288(14):1775–1779. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coulter A. Do patients want a choice and does it work. BMJ. 2010;341:c4989. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stacey D, Bennett CL, Barry MJ, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:CD001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lorig KR, Ritter PL, Laurent DD, Fries JF. Long-term randomized controlled trials of tailored-print and small-group arthritis self-management interventions. Med Care. 2004;42(4):346–354. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000118709.74348.65. April. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Florin D, Dixon J. Public involvement in health care. BMJ. 2004;328(7432):159–161. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7432.159. January 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCarthy D, Blumenthal D. Stories from the sharp end: case studies in safety improvement. Milbank Q. 2006;84(1):165–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2006.00442.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grol RP, Bosch MC, Hulscher ME, Eccles MP, Wensing M. Planning and studying improvement in patient care: the use of theoretical perspectives. Milbank Q. 2007;85(1):93–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00478.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004;82(4):581–629. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuehn BM. IOM sets out “gold standard” practices for creating guidelines, systematic reviews. JAMA. 2011;305(18):1846–1848. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.597. May 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.AGREE Collaboration. Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation (AGREE) Instrument. AGREE Research Trust. 2001 http://www.agreetrust.org. Accessed July 10, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.VanLare JM, Conway PH, Sox HC. Five next steps for a new national program for comparative-effectiveness research. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(11):970–973. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1000096. March 18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Facey K, Boivin A, Gracia J, et al. Patients’ perspectives in HTA: a route to robust evidence and fair deliberation. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2009;26(3):334–340. doi: 10.1017/S0266462310000395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oliver S, Clarke-Jones L, Rees R, et al. Involving consumers in research and development agenda setting for the NHS: developing an evidence-based approach. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8(15):1–148. doi: 10.3310/hta8150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mitton C, Smith N, Peacock S, Evoy B, Abelson J. Public participation in health care priority setting: a scoping review. Health Policy. 2009;91(3):219–228. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pickard S, Sheaff R, Dowling B. Exit, voice, governance and user-responsiveness: the case of English primary care trusts. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(2):373–383. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.12.016. July. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milewa T, Valentine J, Calnan M. Community participation and citizenship in British health care planning: narratives of power and involvement in the changing welfare state. Sociol Health & Illness. 1999;21(4):445–465. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boivin A, Currie K, Fervers B, et al. Patient and public involvement in clinical guidelines: international experiences and future perspectives. Qual & Saf Health Care. 2010;19(5):e22. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2009.034835. October. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin GP. “Ordinary people only”: knowledge, representativeness, and the publics of public participation in healthcare. Sociol Health & Illness. 2008;30(1):35–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.01027.x. January. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Church J, Saunders D, Wanke M, Pong R, Spooner C, Dorgan M. Citizen participation in health decision-making: past experience and future prospects. J Public Health Policy. 2002;23(1):12–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crawford MJ, Rutter D, Manley C, et al. Systematic review of involving patients in the planning and development of health care. BMJ. 2002;325(7375):1263. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7375.1263. November 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nilsen ES, Myrhaug HT, Johansen M, Oliver S, Oxman AD. Methods of consumer involvement in developing healthcare policy and research, clinical practice guidelines and patient information material. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004563.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Legare F, Boivin A, van der Weijden T, et al. Patient and public involvement in clinical practice guidelines: a knowledge synthesis of existing programs. Med Decis Making. 2011;31(6):E45–74. doi: 10.1177/0272989X11424401. September 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Conklin A, Morris ZS, Nolte E. Involving the Public in Healthcare Policy. Cambridge, England: RAND Europe; 2010. December 13. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Contandriopoulos D. A sociological perspective on public participation in health care. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(2):321–330. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00164-3. February. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coulter A, Ellins J. Effectiveness of strategies for informing, educating, and involving patients. BMJ. 2007;335(7609):24–27. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39246.581169.80. July 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abelson J, Montessanti S, Li K, Gauvin F-P, Martin E. Canadian Health Services Research Foundation. Effective strategies for interactive public engagement in the development of healthcare policies and programs. http://www.cfhi-fcass.ca/Libraries/Commissioned_Research_Reports/Abelson_EN_FINAL.sflb.ashx. Published December 2010. Accessed March 12, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abelson J, Gauvin FP. Canadian Policy Research Networks. Assessing the impacts of public participation: concepts, evidence and policy implications. Research Report P06. March 2006. http://www.cprn.org/documents/42669_fr.pdf. Accessed March 12, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patton MQ. Utilization-Focused Evaluation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hulscher MEJL, Laurant MGH, Grol RPTM. Process evaluation on quality improvement interventions. Qual & Saf Health Care. 2003;12(1):40–46. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.1.40. March. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boivin A, Lehoux P, Lacombe R, Burgers J, Grol R. Involving patients in setting priorities for healthcare improvement: a cluster randomized trial. Implement Sci. 2014;9:24. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-9-24. February. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rowe G, Frewer LJ. Public participation methods: a framework for evaluation. Sci Technol & Hum Values. 2000;25(1):3. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Renn O, Webler T, Wiedemann P. Fairness and Competence in Citizen Participation: Evaluating Models for Environmental Discourse. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arnstein S. A ladder of citizen participation in the USA. J Am Inst Planners. 1969;35(4):216–224. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tritter JQ, McCallum A. The snakes and ladders of user involvement: moving beyond Arnstein. Health Policy. 2006;76(2):156–168. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wait S, Nolte E. Public involvement policies in health: exploring their conceptual basis. Health Econ, Policy & Law. 2006;1(2):149–162. doi: 10.1017/S174413310500112X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oliver SR, Rees RW, Clarke-Jones L, et al. A multidimensional conceptual framework for analysing public involvement in health services research. Health Expect. 2008;11(1):72–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2007.00476.x. March. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boote J, Telford R, Cooper C. Consumer involvement in health research: a review and research agenda. Health Policy. 2002;61(2):213–236. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(01)00214-7. August. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rowe G, Frewer LJ. A Typology of public engagement mechanisms. Sci Technol & Hum Values. 2005;30(2):251. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fearon JD. Deliberation as discussion. In: Elster J, editor. Deliberative Democracy. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1998. pp. 44–68. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fischer F. Policy deliberation: confronting subjectivity and emotional expression. Crit Policy Stud. 2009;3(3):407–420. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bohman J. Public Deliberation: Pluralism, Complexity, and Democracy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davies C, Wetherell M, Barnett E. Citizens at the Centre: Deliberative Participation in Healthcare Decisions. Bristol, England: Policy Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chambers S. Deliberative democratic theory. Ann Rev Polit Sci. 2003;6(1):307–326. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Collins HM, Evans R. The third wave of science studies: studies of expertise and experience. Soc Stud Sci. 2002;32(2):235–296. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martin GP. Representativeness, legitimacy and power in public involvement in health-service management. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(11):1757–1765. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.024. December. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barnes M, Newman J, Knops A, Sullivan H. Constituting “the public” in public participation. Public Admin. 2003;81(2):379–399. July. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harrison S, Mort M. Which champions, which people? Public and user involvement in health care as a technology of legitimation. Soc Policy & Admin. 1998;32(1):60–70. April. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Parkinson J. Hearing voices: negotiating representation claims in public deliberation. Br J Polit & Int Relations. 2004;6(3):370–388. August. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pellizzoni L. The myth of the best argument: power, deliberation and reason. Br J Sociol. 2001;52(1):59–86. doi: 10.1080/00071310020023037. March. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carpini MXD, Cook FL, Jacobs LR. Public deliberation, discursive participation, and citizen engagement: a review of the empirical literature. Ann Rev Polit Sci. 2004;7(1):315–344. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sunstein C. The law of group polarization. J Polit Philos. 2002;10(2):175–195. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boivin A, Green J, van der Meulen J, Légaré F, Nolte E. Why consider patients’ preferences? A discourse analysis of clinical practice guideline developers. Med Care. 2009;47(8):908–915. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181a81158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Abelson J, Forest PG, Eyles J, Smith P, Martin E, Gauvin FP. Deliberations about deliberative methods: issues in the design and evaluation of public participation processes. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(2):239–251. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00343-x. July. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Boivin A, Lehoux P, Lacombe R, Lacasse A, Burgers J, Grol R. Target for improvement: a cluster randomized trial of public involvement in quality indicator prioritization (intervention development and study protocol) Implement Sci. 2011;6:45. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative Methods for Health Research. London, England: Sage; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Martin GP. Public deliberation in action: emotion, inclusion and exclusion in participatory decision making. Crit Soc Policy. 2012;32(2):163–183. May 1. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bucchi M, Neresini F. Science and public participation. In: Hackett EJ, Amsterdamska O, Lynch ME, Wajcman J, editors. The Handbook of Science and Technology Studies. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2008. pp. 449–472. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Edmond G, Mercer D. Scientific literacy and the jury: reconsidering jury competence. Public Understanding of Sci. 1997;6:329–357. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lehoux P, Daudelin G, Demers-Payette O, Boivin A. Fostering deliberations about health innovation: what do we want to know from publics. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:2002–2009. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fishkin J, Luskin R. Deliberative polling and public consultation. Parliamentary Affairs. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ryfe D. Does deliberative democracy work. Ann Rev Polit Sci. 2005;8:49–71. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hendriks C. Institutions of deliberative democratic processes and interest groups: roles, tensions and incentives. Austral J Public Admin. 2002;61(1):64–75. April. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lehoux P, Daudelin G, Abelson J. The unbearable lightness of citizens with public deliberation processes. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(12):1843–1850. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Abelson J, Forest PG, Eyles J, Casebeer A, Martin E, Mackean G. Examining the role of context in the implementation of a deliberative public participation experiment: results from a Canadian comparative study. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:2115–2128. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rowe G, Frewer LJ. Evaluating public-participation exercises: a research agenda. Sci, Technol & Hum Values. 2004;29(4):512. [Google Scholar]