Abstract

Time-lapse imaging is a technique that allows for the direct observation of the process of morphogenesis, or the generation of shape. Due to their optical clarity and amenability to genetic manipulation, the zebrafish embryo has become a popular model organism with which to perform time-lapse analysis of morphogenesis in living embryos. Confocal imaging of a live zebrafish embryo requires that a tissue of interest is persistently labeled with a fluorescent marker, such as a transgene or injected dye. The process demands that the embryo is anesthetized and held in place in such a way that healthy development proceeds normally. Parameters for imaging must be set to account for three-dimensional growth and to balance the demands of resolving individual cells while getting quick snapshots of development. Our results demonstrate the ability to perform long-term in vivo imaging of fluorescence-labeled zebrafish embryos and to detect varied tissue behaviors in the cranial neural crest that cause craniofacial abnormalities. Developmental delays caused by anesthesia and mounting are minimal, and embryos are unharmed by the process. Time-lapse imaged embryos can be returned to liquid medium and subsequently imaged or fixed at later points in development. With an increasing abundance of transgenic zebrafish lines and well-characterized fate mapping and transplantation techniques, imaging any desired tissue is possible. As such, time-lapse in vivo imaging combines powerfully with zebrafish genetic methods, including analyses of mutant and microinjected embryos.

Keywords: Developmental Biology, Issue 83, zebrafish, neural crest, time-lapse, transgenic, morphogenesis, craniofacial, head, development, confocal, Microscopy, In vivo, movie

Introduction

Craniofacial morphogenesis is a complex multi-step process that requires coordinated interactions between multiple cell types. The majority of the craniofacial skeleton is derived from neural crest cells, many of which must migrate from the dorsal neural tube into transient structures called pharyngeal arches1. As with many tissues, morphogenesis of the craniofacial skeleton is more complicated than can be understood by static images of embryos at specific developmental time points. Although it is time-consuming to perform, in vivo time-lapse microscopy provides a continuous look at a developing embryo's cells and tissues. Each image in a time-lapse series lends context to the others, and helps an investigator move toward deducing why a phenomenon occurs rather than deducing what is occurring at that time.

In vivo imaging is thus a powerful descriptive tool for experimental approaches to deconstruct the pathways that guide morphogenesis. The zebrafish Danio rerio is a popular genetic model of vertebrate embryonic development, and is particularly well suited for in vivo imaging of morphogenesis. Modern, convenient methods for transgenesis and genomic modification are rapidly advancing the number of tools available to zebrafish researchers. These tools enhance already robust methods for genetic manipulation and microscopy. In vivo imaging of almost any tissue in almost any desired genetic context is closer to reality than fantasy.

Morphogenetic movements of the pharyngeal arches are guided by signaling interactions between the neural crest and the adjacent epithelia, both ectoderm and endoderm. There are numerous signaling molecules expressed by the epithelia that are necessary to drive the morphogenesis of craniofacial skeletal elements. Among these signaling molecules, Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) is critically important for craniofacial development2-8. Shh is expressed by both the oral ectoderm and pharyngeal endoderm2,6,9,10. The expression of Shh in the endoderm regulates morphogenetic movements of the arches10, patterning of neural crest within the arches10, and growth of the craniofacial skeleton11.

Bmp signaling is also critically important for craniofacial development12 and may alter morphogenesis of the pharyngeal arches. Bmp signaling regulates dorsal/ventral patterning of crest within the pharyngeal arches13,14. Disruption of smad5 in zebrafish causes severe palatal defects and a failure of the Meckel's cartilages to fuse appropriately at the midline15. In addition, the mutants also display reductions and fusion in the ventral cartilage elements, with the 2nd, 3rd, and sometimes 4th pharyngeal arch elements fused at the midline15. These fusions strongly suggest that Bmp signaling directs the morphogenesis of these pharyngeal elements.

Pdgf signaling is necessary for craniofacial development, but has unknown roles in pharyngeal arch morphogenesis. Both mouse and zebrafish Pdgfra mutants have profound midfacial clefting16-18. At least in zebrafish this midfacial clefting is due to a failure of proper neural crest cell migration16. Neural crest cells continue to express pdgfra after they have entered the pharyngeal arches. Additionally, Pdgf ligands are expressed by facial epithelia and within the pharyngeal arches16,19,20, thus Pdgf signaling could also play a role in morphogenesis of the pharyngeal arches following migration. However, analyses of the morphogenesis of the pharyngeal arches in pdgfra mutants have not been performed.

Here, we demonstrate in vivo confocal microscopy of pharyngula-stage transgenic zebrafish and describe the morphogenesis of the pharyngeal arches within this period. We further demonstrate tissue behaviors that are affected by mutations that disrupt the Bmp, Pdgf, and Shh signaling pathways.

Protocol

1. Animal Husbandry and Mutant Alleles

Raise and breed zebrafish as described21.

Zebrafish mutant alleles used in this study were pdgfra b1059 16, smad5 b1100 22, and smob577 23. Sources for these zebrafish strains include ZIRC.

2. Preparation of Solutions and Implements

Note: All solutions and implements can be made in advance and stored for future use.

Make embryo media (EM) as previously described21.

Make 4 g/L MS-222 (Tricaine). Dissolve 4 g disodium phosphate (Na2HPO4) in 450 ml sterile water. Add 2 g MS-222 to the solution. Adjust pH to within 7.0-7.2. Add sterile water to a total volume of 500 ml.

Optional: Make 4 g/L clove oil. Weigh 0.2 g pure clove oil in a 50 ml conical tube. Add EM to a total volume of 50 ml. Store at 4 °C.

Make 3% methylcellulose. Bring 50 ml of EM + 0.1 M HEPES to a boil. Remove from heat. Stir in 1.5 g methylcellulose until the solution is homogeneous. Store at 4 °C.

Make 0.2% agarose. Add 0.1 g agarose to 50 ml EM. Bring EM to a boil in the microwave or on a hotplate and verify that the agarose has dissolved. Aliquot into 500 μl volumes in microcentrifuge tubes and store at 4 °C. Note: Volumes can be adjusted as needed.

Make capillary pokers. Place a drop of super glue inside a 0.9 mm ID capillary tube. Insert a 4-5 cm length of 6 lb test monofilament fishing line inside the capillary tube such that approximately 3-4 mm of line extends beyond the end of the tube.

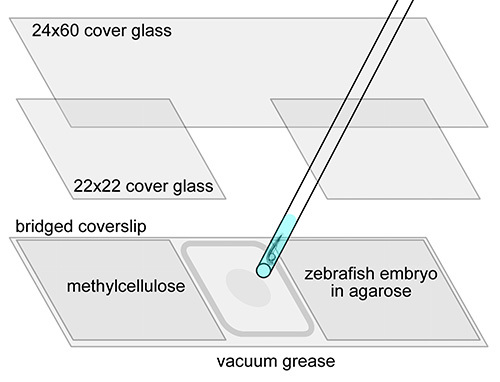

Make two bridged coverslips per specimen. Super-glue 22 x 22-1 cover glass onto each end of a 24 x 60-1 cover glass leaving the middle free. Make singles (1 small cover glass per end) for embryos less than a day old, doubles (2 small cover glasses on top of each other per end) for embryos one to four days old, or triples (3 small cover glasses on top of each other per end) for embryos five days or older.

Fill a 10 ml syringe with high vacuum grease. Note: Vacuum grease serves as a sealant to prevent dehydration of specimens over long periods of time, and has low potential for toxicity compared to more volatile sealants.

3. Mounting Zebrafish Embryos for Confocal Microscopy (See Figure 1)

Prepare anesthetic medium. Melt an aliquot of 0.2% agarose by microwaving in 20 sec intervals until completely liquid. Mix 8 µl of MS-222 into 192 µl of 0.2% agarose or 5 µl of 4 g/L clove oil into 195 µl of 0.2% agarose. Maintain in a 42 °C heating block. Note: Long exposure to MS-222 causes stronger developmental delays than clove oil does in embryonic zebrafish24.

If necessary: Manually dechorionate unhatched transgenic embryos to be analyzed just prior to analysis. Using forceps, slowly tear the chorion open until the embryo is freed.

Anesthetize the zebrafish embryos. Add 1 ml of a 4 g/L stock of MS-222 to 24 ml of embryo media. Alternatively, add 390 µl of 4 g/L clove oil to 24 ml of fish water24. Note: Clove oil acts slowly so perform this step at least 15-20 min before time-lapse microscopy.

Place a bead of vacuum grease around the center space of an upward-facing bridged coverslip. Slowly push the vacuum grease out of the syringe, making a smooth, continuous bead that is adjacent to and inside of the bridges and the edge of the coverslip.

Spread a circle of 4% methylcellulose in the middle of the bridged coverslip using a wooden applicator.

Transfer the embryo to be imaged. When the embryo is anesthetized draw it up into a glass pipette. Hold the pipette up vertically to allow the embryo to sink to the bottom of the liquid in the pipette. Move the pipette into the agarose solution and allow the embryo to drop into the agarose. Do not expel the liquid.

Place the specimen. Draw some agarose solution and the embryo into the pipette. Expel the embryo in a drop of agarose solution on top of the methylcellulose. Use a capillary poker to push the embryo downward onto the methylcellulose and orient the embryo as desired for imaging.

- Seal the specimen.

- Place one bridged coverslip on top of the mounted one, facing downward. Apply even pressure to both sides of the sandwiched coverslips until the bridges make direct contact and the agarose drop seals to both coverslips. Verify that the embryo is properly oriented.

- Rub a wooden applicator along the glass to smooth out cracks and gaps in the vacuum grease bead. Wipe away excess grease from the edges.

4. Time-lapse Confocal Imaging of Transgenic Zebrafish Embryos

(This protocol has been optimized for a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope using ZEN imaging software, and can be modified for use with other systems.)

Activate equipment. Turn on the confocal microscope and any external laser devices. Turn on the computer connected to the confocal microscope. Open confocal imaging software and select "Start System" to activate image acquisition controls.

Prepare heated stage. Lower the staging platform of the confocal microscope and move the objective lenses out of position. Replace the default stage with an electronic heated stage. Turn on the controller for the heated stage and set the temperature for 29.5 °C.

Position the specimen in the field of view. Place the mounted specimen on the stage. Move the 20X objective lens into position and raise the staging platform. Activate the visible light emitter and look through the eyepieces. Center the embryo's head in the field of view.

- Define experiment settings.

- Activate fluorescence channels by selecting the fluorescent wavelength to be detected and choose color lookup tables (LUT) for each channel. If necessary, use manual controls in the software to turn on the requisite lasers (e.g. 561 nm for RFP). For each fluorescence channel, set the laser intensity to 10.0 and the photomultiplier voltage (HV or gain) between 600-700. Set the averaging to 4 and the bit depth to 16 bit.

- Activate the Z-stack and time series modules. Set the pinhole for a 5 µm or smaller Z-resolution, and set the Z-interval to the suggested optimal distance. Note: Generally, 5 µm Z-resolution allows each Z-stack image to be collected quickly enough for a "snapshot" of the embryo at a particular time point while also resolving individual cells. Lowering the averaging also reduces the amount of time per image.

- Define the desired time interval between images (usually 10-20 min) and the total length of the experiment.

- Set positional information.

- Turn the camera to live mode. Adjust focus and increase laser intensity if necessary to see fluorescence. Set the digital zoom to 0.6 for a wider view, if desired.

- Position the stage such that all structures of interest are visible and there is room in the field of view for outgrowth dorsally and anteriorly. Focus through the embryo to the upper and lower limits of fluorescence. Set the first and last Z-stack slice positions at least 100 µm or more beyond these limits.

- Optimize fluorescence intensity.

- Set the display LUT to range indicator. Fluorescent structures should now appear white, and the rest of the field of view should be blue (no detection) or black.

- Increase HV/gain to a level just below where saturated (red) pixels appear. If necessary, adjust offset so a majority of the background is not detected (blue). Note: Smaller pinhole diameter and increased laser intensity both improve image definition, but laser intensity must be kept low to preserve living tissues. Increased HV/gain and pinhole diameter (<5 µm) are generally preferable to increased laser intensity.

- Keep the pinhole diameter wide enough to collect images in a timely fashion, averaging sets to 4. The Z-interval should always be set to the suggested optimal distance for the pinhole diameter. Perform short scans (averaging = 1) with different settings, and use the minimum laser intensity that achieves desired resolution.

Run the experiment for the desired length of time. Afterward, remove embryo from the heated stage and slowly separate the coverslips. Submerge the coverslip and embryo in EM in a 30 mm Petri dish. Using a glass pipette gently wash the embryo off of the coverslip and remove the coverslip from the Petri dish. Place the embryo into a 28.5 °C incubator to continue to develop.

Compare growth. At the end of the experiment, take individual Z-stack images of agarose-mounted sibling embryos that were similarly staged to the specimen at the beginning of the experiment, but were raised in EM in a 28.5 °C incubator.

Measure pharyngeal arches, as needed. Measurements can be performed in some confocal software suites. Measurements found here were performed using Fiji25 by importing and Z-projecting .lsm files of individual frames.

Representative Results

In wild-type embryos, following neural crest population, the pharyngeal arches elongate along the anterior/posterior and dorsal/ventral axes while moving in a rostral direction (Movie 1). At 30 hours post-fertilization (hpf), the anterior/posterior length of the first pharyngeal arch is between 1.8-1.9 times its dorsal/ventral height. Dorsal/ventral elongation proceeds steadily, faster than anterior/posterior extension until 36.5 hpf. From here, dorsal/ventral height plateaus around 104 µm through 48 hpf. Anterior/posterior extension continues through 48 hpf, with overall anterior/posterior length increasing from under 1.5 times the dorsal/ventral height at 36.5 hpf to 1.95 times the dorsal/ventral height at 48 hpf.

At its anterior end, the first pharyngeal arch forms maxillary (dorsal) and mandibular (ventral) domains separated by the oral ectoderm. The maxillary domain of the first pharyngeal arch is measured from its distal tip to the posterior apex of the oral ectoderm. It grows at a rate approximated by linear regression at 4.6 µm/hr (r2 = 0.9374) between 30-48 hpf and is about 104 µm long at 48 hpf (Movie 1).

Pharyngeal arches 3-7 all form from the segmentation of a single mass of neural crest cells via the pharyngeal endoderm26. Between 30-38 hpf, the 5th through 7th pharyngeal arches separate from the mass, the 3rd and 4th arches already having separated. Around 37 hpf, the 3rd pharyngeal arch begins to move medially to the 2nd arch. Laterally, the 7th pharyngeal arch overtakes the 5th and 6th arches in rostral movement by 48 hpf, leaving the 3rd through 6th arches medial to the 2nd and 7th arches (Movie 1).

It is important to note that although the convention is to describe the morphology in hpf, microscopy slightly delays zebrafish growth compared to similarly staged embryos grown in a 28.5 °C incubator. For example, after 19 hr of microscopy, the distance between the eye and ear of an imaged wild-type embryo was approximately 81.7 µm, and the average eye-ear distance for two sibling embryos imaged immediately afterward was 71 µm. Therefore, embryos are likely to be slightly younger than the staging series27.

These morphogenetic movements are greatly disrupted in smo mutants. As previously described, zebrafish smo mutants fail to form a maxillary condensation of the first arch, and by 48 hpf the first pharyngeal arch is completely caudal to the eye2. Posterior arch movements are also disrupted10. The 3rd pharyngeal arch fails to move medial to the 2nd pharyngeal arch, and Movie 2 shows that the 7th pharyngeal arch fails to migrate rostrally to overlap with more anterior arches by 48 hpf.

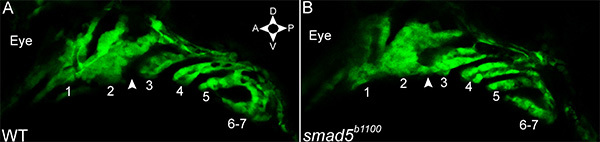

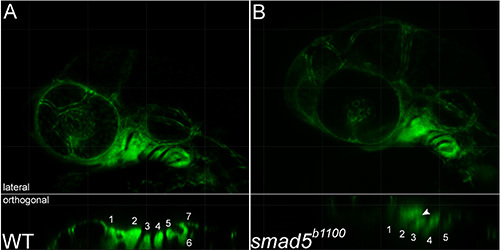

Zebrafish smad5b1100 mutants have numerous craniofacial defects, including a near-complete loss of the palatal skeleton and ventral fusions between the 2nd, 3rd, and sometimes 4th pharyngeal arch skeletal elements15, suggesting that there may be defects to pharyngeal arch morphogenesis. Indeed, static confocal imaging demonstrated fusions in the ventral domains of the 2nd and 3rd arches are apparent by 32 hpf (Figure 2). Using time-lapse confocal microscopy, we analyzed the morphogenesis of the pharyngeal arches in smad5 mutants. In time-lapse analyses, fusions between the 2nd and 3rd arches appear first at 32 hpf, consistent with the static analysis (Movie 3, Figure 3). Additionally, smad5 mutants have disrupted outgrowth of the first pharyngeal arch (Movie 3). At 30 hpf, the anterior/posterior length of the first pharyngeal arch (186.8 µm) is over 35% longer than in wild-type, and is 2.5 times the dorsal/ventral height of the first pharyngeal arch in a smad5 mutant. However, as the posterior edge moves rostrally, the anterior/posterior length of the first pharyngeal arch decreases almost 40 µm between 30-39 hpf and then regains this length by 48 hpf. The dorsal/ventral height of the first pharyngeal arch decreases steadily to 62.3 µm from 30-48 hpf. Failure of anterior extension during this time is reflected in the maxillary domain, which is exceptionally long (85 µm) at 30 hpf compared to wild-type. Maxillary length decreases at a rate approximated by linear regression at 4.4 µm/hr (r2 = 0.9032) from 30-36 hpf, and stays fairly consistent thereafter. Here, time-lapse imaging demonstrates unique tissue movements that may account for the loss of the palatal skeleton observed in smad5 mutants.

While the expression of Pdgf family members suggests that it may be broadly involved in pharyngeal arch morphogenesis, movement of the posterior arches appears normal in pdgfra mutants. It is morphogenesis of the first pharyngeal arch that appears specifically disrupted (Movie 4). The overall size of the first pharyngeal arch is reduced relative to wild-type, and the maxillary domain appears highly plastic, with cells condensing and withdrawing over time. This results in a failure of maxillary elongation, which peaks around 39 hpf at 56.5 µm. At 48 hpf, the maxillary domain measures only 44.1 µm. Collectively, these findings show that careful time lapse analyses can provide details of morphogenesis potentially lost in static analyses.

Figure 1.

Schematic of bridged coverslip construction and embryo mounting for confocal microscopy.

Figure 1.

Schematic of bridged coverslip construction and embryo mounting for confocal microscopy.

Figure 2. The second and third arches fuse in smad5 mutants. (A, B) Single Z slices from a (A) fli1:egfp and a (B) fli1:egfp;smad5b1100 mutant embryo. (A) In embryos wild-type for smad5, neural crest cells in the second and third arch are separated by the second pharyngeal pouch (arrowhead). (B) Neural crest cells at the ventral limit of the second and third arches intermingle in smad5 mutants (arrowhead). Pharyngeal arches are numbered. Click here to view larger image.

Figure 2. The second and third arches fuse in smad5 mutants. (A, B) Single Z slices from a (A) fli1:egfp and a (B) fli1:egfp;smad5b1100 mutant embryo. (A) In embryos wild-type for smad5, neural crest cells in the second and third arch are separated by the second pharyngeal pouch (arrowhead). (B) Neural crest cells at the ventral limit of the second and third arches intermingle in smad5 mutants (arrowhead). Pharyngeal arches are numbered. Click here to view larger image.

Figure 3. Loss of smad5 function results in disrupted pharyngeal arch morphogenesis. (A, B, upper panels) Projections and (lower panels) orthogonal views of arch fusion in Movie 3. Fusion of arches two and three is evident, arrowhead. Pharyngeal arches are numbered. Click here to view larger image.

Figure 3. Loss of smad5 function results in disrupted pharyngeal arch morphogenesis. (A, B, upper panels) Projections and (lower panels) orthogonal views of arch fusion in Movie 3. Fusion of arches two and three is evident, arrowhead. Pharyngeal arches are numbered. Click here to view larger image.

Movie 1. Development of the pharyngeal arches in a wild-type (fli1:egfp) embryo from 30-48 hpf. Anterior to the left, dorsal to the top. Click here to view movie.

Movie 2. Medial movements of the pharyngeal arches fail in smo mutants (fli1:egfp;smob577). Anterior to the left, dorsal to the top. 30-48 hpf. Click here to view movie.

Movie 3. The 2nd and 3rd arches fuse in smad5 mutants (fli1:egfp;smad5b1100). Anterior to the left, dorsal to the top. Series of (A) projections, 30-48 hpf, and (B) single Z slices, 30-40 hpf. Click here to view movie.

Movie 4. Elongation of the maxillary region fails in pdgfra mutants (fli1:egfp;pdgfrab1059). Anterior to the left, dorsal to the top. 30-48 hpf. Click here to view movie.

Discussion

Time-lapse confocal microscopy is a powerful tool for the analysis of development. Here, we demonstrate the method's usefulness in studying pharyngeal arch morphogenesis in zebrafish that are mutant for important signaling pathways using a transgenic that labels neural crest cells. In addition to tissue-level analyses, time lapse analyses are also applicable to analyses at a cellular scale28. Many widely used zebrafish methods can also be incorporated into time-lapse microscopy experiments, including microinjection of morpholinos, mRNAs, or transgenic constructs, as well as transplants between embryos. Analysis of multiple developing tissues is limited only by the ability to fluorescently label tissues and by a confocal microscope's capability to detect the desired number of different fluorophores without crosstalk. The number of individuals that can be imaged from a clutch of zebrafish embryos is severely constrained, but advanced techniques allow automated imaging of several embryos in the same time period. This is especially useful when seeking to perform time-lapse analysis of a mutant that is not easily identified at early time points.

When performing measurements from time-lapse confocal images, it is important to consider that some developmental delay is caused by the process. Developmental delays are not uncommon in mutant embryos as well, so imaging of sibling controls is necessary for both mutant/manipulated embryos as well as wild-type controls. Even once controlled for staging, comparative measurement of fluorescence-labeled structures is difficult. Fluorescence intensity can be highly variable between individuals and between separate parts of the same structure. Thus, nondiscrete quantitative measurements have a degree of subjectivity, and we recommend that more than one individual perform measurements to ensure consistency. Investigators must also be disciplined in orienting embryos for comparative measurement consistently, as failure to do so will cause the appearance of morphological differences where there may be none. Movements of specimen embryos can outright ruin an experiment, and we find that adding anesthetic after the microwaved agarose has been allowed to thicken reduces its efficacy in sedating embryos.

Though difficult to acquire, time-lapse microscopy data have obvious advantages over static images in comparing morphogenesis qualitatively. Static images will often allow easy measurement of structures at a certain time point, but give no indication of tissue behaviors leading up to or following that stage. Such information is crucial when studying the interactions of two or more separate tissues undergoing morphogenesis. In order to obtain the best overall characterization of morphogenesis, it is beneficial to perform both time-lapsed and static analyses to best utilize the advantages of each method. In the time-lapsed analyses, the dynamic cell and tissue behaviors can be analyzed and, in static analyses, large numbers of embryos can be examined to gain the best understanding of variability. The growing number of zebrafish transgenic lines and advancement of other techniques will make time-lapse confocal microscopy of multiple tissues commonplace, as real-time in vivo data becomes the gold standard among morphogenesis researchers.

Disclosures

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Acknowledgments

We thank Melissa Griffin and Jenna Rozacky for their expert fish care. PDM thanks EGN for writing assistance, generosity, and patience. This work was supported by NIH/NIDCR R01DE020884 to JKE.

References

- Trainor PA, Melton KR, Manzanares M. Origins and plasticity of neural crest cells and their roles in jaw and craniofacial evolution. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2003;47:541–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhart JK, Swartz ME, Crump JG, Kimmel CB. Early Hedgehog signaling from neural to oral epithelium organizes anterior craniofacial development. Development. 2006;133:1069–1077. doi: 10.1242/dev.02281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada N, et al. Hedgehog signaling is required for cranial neural crest morphogenesis and chondrogenesis at the midline in the zebrafish skull. Development. 2005;132:3977–3988. doi: 10.1242/dev.01943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roessler E, et al. Mutations in the human sonic hedgehog gene cause holoprosencephaly. Nat. Genet. 1996;14:357–360. doi: 10.1038/ng1196-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong J, Mao J, Tenzen T, Kottmann AH, McMahon AP. Hedgehog signaling in the neural crest cells regulates the patterning and growth of facial primordia. Genes Dev. 2004;18:937–951. doi: 10.1101/gad.1190304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu D, Marcucio RS. A SHH-responsive signaling center in the forebrain regulates craniofacial morphogenesis via the facial ectoderm. Development. 2009;136:107–116. doi: 10.1242/dev.026583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordero D, et al. Temporal perturbations in sonic hedgehog signaling elicit the spectrum of holoprosencephaly phenotypes. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;114:485–494. doi: 10.1172/JCI19596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westphal H, Beachyr PA. Cyclopia and defective axial patterning in mice lacking Sonic hedgehog gene function. Nature. 1996;383:3. doi: 10.1038/383407a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore-Scott BA, Manley NR. Differential expression of Sonic hedgehog along the anterior-posterior axis regulates patterning of pharyngeal pouch endoderm and pharyngeal endoderm-derived organs. Dev. Biol. 2005;278:323–335. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz ME, Nguyen V, McCarthy NQ, Eberhart JK. Hh signaling regulates patterning and morphogenesis of the pharyngeal arch-derived skeleton. Dev. Biol. 2012;369:65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balczerski B, et al. Analysis of Sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling mutants reveals endodermal requirements for the growth but not dorsoventral patterning of jaw skeletal precursors. Dev. Biol. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nie X, Luukko K, Kettunen P. BMP signalling in craniofacial development. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2006;50:511–521. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.052101xn. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander C, et al. Combinatorial roles for BMPs and Endothelin 1 in patterning the dorsal-ventral axis of the craniofacial skeleton. Development. 2011;138:5135–5146. doi: 10.1242/dev.067801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuniga E, Rippen M, Alexander C, Schilling TF, Crump JG. Gremlin 2 regulates distinct roles of BMP and Endothelin 1 signaling in dorsoventral patterning of the facial skeleton. Development. 2011;138:5147–5156. doi: 10.1242/dev.067785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz ME, Sheehan-Rooney K, Dixon MJ, Eberhart JK. Examination of a palatogenic gene program in zebrafish. Dev. Dyn. 2011;240:2204–2220. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhart JK, et al. MicroRNA Mirn140 modulates Pdgf signaling during palatogenesis. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:290–298. doi: 10.1038/ng.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P. The PDGF alpha receptor is required for neural crest cell development and for normal patterning of the somites. Development. 1997;124:2691–2700. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.14.2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallquist MD, Soriano P. Cell autonomous requirement for PDGFRalpha in populations of cranial and cardiac neural crest cells. Development. 2003;130:507–518. doi: 10.1242/dev.00241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho L, Symes K, Yordan C, Gudas LJ, Mercola M. Localization of PDGF A and PDGFR alpha mRNA in Xenopus embryos suggests signalling from neural ectoderm and pharyngeal endoderm to neural crest cells. Mech. Dev. 1994;48:165–174. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(94)90057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Korzh V, Balasubramaniyan NV, Ekker M, Ge R. Platelet-derived growth factor A (pdgf-a) expression during zebrafish embryonic development. Dev. Genes Evol. 2002;212:298–301. doi: 10.1007/s00427-002-0234-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerfield M. The Zebrafish Book; A guide for the laboratory use of zebrafish (Brachydanio rerio) 1993.

- Sheehan-Rooney K, Swartz ME, Lovely CB, Dixon MJ, Eberhart JK. Bmp and Shh Signaling Mediate the Expression of satb2 in the Pharyngeal Arches. PloS one. 2013;8:e59533. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga ZM, et al. Zebrafish smoothened functions in ventral neural tube specification and axon tract formation. Development. 2001;128:3497–3509. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.18.3497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grush J, Noakes DLG, Moccia RD. The efficacy of clove oil as an anesthetic for the zebrafish, Danio rerio. 2004;1:46–53. doi: 10.1089/154585404774101671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin J, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crump JG, Maves L, Lawson ND, Weinstein BM, Kimmel CB. An essential role for Fgfs in endodermal pouch formation influences later craniofacial skeletal patterning. Development. 2004;131:5703–5716. doi: 10.1242/dev.01444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel CB, Ballard WW, Kimmel SR, Ullmann B, Schilling TF. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev. Dyn. 1995;203:253–310. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandre P, Reugels AM, Barker D, Blanc E, Clarke JD. Neurons derive from the more apical daughter in asymmetric divisions in the zebrafish neural tube. Nat. Neurosci. 2010;13:673–679. doi: 10.1038/nn.2547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]