Abstract

Tumor endothelial marker 1 (TEM1/endosialin) is a tumor vascular marker highly overexpressed in multiple human cancers with minimal expression in normal adult tissue. In this study, we report the preparation and evaluation of 124I-MORAb-004, a 124I-labeled humanized monoclonal antibody targeting an extracellular epitope of human TEM1 (hTEM1), for its ability to specifically and sensitively detect vascular cells expressing hTEM1 in vivo.

Methods

MAb MORAb-004 was directly iodinated with 125I and 124I, and in vitro binding and internalization parameters were characterized. The in vivo behavior of radioiodinated-MORAb-004 was characterized in mice bearing subcutaneous ID8 tumors enriched with mouse endothelial cells expressing hTEM1, or control tumors, by biodistribution studies and small animal immuno-PET studies.

Results

MORAb-004 was radiolabeled with high efficiency and isolated in high purity. In vitro studies demonstrated specific and sensitive binding of MORAb-004 to MS1 mouse endothelial cells expressing hTEM1, with no binding to control MS1 cells. 125I-MORAb-004 and 124I MORAb-004 both had an immunoreactivity of approximately 90%. In vivo biodistribution experiments revealed rapid, highly specific and sensitive uptake of MORAb-004 in MS1-TEM1 tumors at 4 h (153.2 ± 22.2 percent of injected dose per gram [%ID/g]), 24 h (127.1 ± 42.9 %ID/g), 48 h (130.3 ± 32.4 %ID/g), 72 h (160.9 ± 32.1 %ID/g), and 6 d (10.7 ± 1.8 %ID/g). Excellent image contrast was observed with 124I-immuno-PET. MORAb-004 uptake was statistically higher in TEM1-positive tumors versus control tumors, as measured by biodistribution and immuno-PET studies. Binding specificity was confirmed by blocking studies using excess nonlabeled MORAb-004.

Conclusion

In our preclinical model, with hTEM1 exclusively expressed on engineered murine endothelial cells that integrate into the tumor vasculature, 124I-MORAb-004 displays high tumor–to–background tissue contrast fordetection of hTEM1 in easily accessible tumor vascular compartments. These studies strongly suggest the clinical utility of 124I-MORAb-004 immunoPET in assessing TEM1 tumor-status.

Keywords: Immuno-PET, TEM1, Endosialin, MORAb-004, mononclonal antibodies

INTRODUCTION

Tumor vascular markers (TVMs) are attractive targets for antibody-based diagnostics and therapeutics. Targeting tumor vasculature rather than tumor cells themselves has several advantages. Among these, tumor vasculature expresses unique molecular targets that are absent in normal vasculature, vascular targets are less likely to be lost due to adaptation or mutations, and TVMs are readily accessible to blood circulation. Consequently, TVMs are attractive targets for antibody-based cancer diagnosis of molecular phenotype and personalized therapy (1-3).

Tumor endothelial marker 1 (TEM1)/endosialin/CD248 is emerging as a robust TVM in multiple human cancers (4, 5). These early studies concluded that TEM1-positive cells are tumor endothelial cells. However, nearly all carcinomas, including ovarian, lung and breast cancer, have TEM1 expression that is restricted to tumor-associated perivascular cells (pericytes) and stromal cells (6-8) (9-12). In sarcomas, ranging from neuroblastoma to colorectal cancers to highly invasive glioblastomas, TEM1 expression is found in malignant cancer cells, in addition to tumor perivascular cells and stromal cells (6, 13-15). TEM1 is a heavily O-glycosylated 175 kDa type I transmembrane protein of the C-type lectin-like receptor family which shares overall architecture with thrombomodulin (11). The extracellular domain contains a C-type lectin-like domain, three EGF-like repeats, and a proline-rich mucin domain, whereas the intracellular domain is fairly short (51 amino acids), with three potential phosphorylation sites and a C-terminal PDZ-binding motif (16). This surface protein is not shed, but little is known on its modulation or internalization in response to epitope engagement by antibodies and other TEM1-targeted therapies. Its high expression on the tumor vasculature across a wide variety of solid human cancers, with limited expression in normal adult tissue, makes human TEM1 an ideal target for exogenous antibody therapies and diagnostics (17-19).

A humanized IgG monoclonal antibody (mAb) directed to human endosialin/TEM1 (MORAb-004; Morphotek, Inc.) (20) is currently being explored in phase I/II clinical trials for its potential anti-angiogenic and anti-neoplastic activity in solid and soft-tissue tumors. The efficacy of this anti-TEM1 mAb against solid tumors is also being investigated in combination with chemotherapy (21). The mechanism of action of MORAb-004 in vivo appears to be mediated by inhibiting the cell surface association of TEM1 with extracellular matrix proteins including fibronectin, collagen I/IV (20), and the Mac-2 BP/90K protein (22).

A critical factor in targeted therapy is evaluating the presence and amount of the specific target in the tumor and its relevance to the disease state. The overexpression of TEM1 on tumor vasculature provides a potential target for the specific diagnosis and therapy of TEM1-positive tumors. Initial clinical experience by immunohistochemistry analysis reveals that high TEM1 levels correlate with high tumor grade and aggressive tumor behavior (7, 23). Along with other pathologic procedures and tests, noninvasive nuclear imaging is often used to assess the status of the specific target. Multiple antibodies against TEM1 have been reported (17, 24), however there is limited demonstration of whether this TVM can function as a target for tumor detection in diagnostic nuclear medicine. Considering the superiority of PET over single-photon scintigraphy, the development of a human TEM1-specific PET radioimmunoconjugates is a worthwhile pursuit. Because of its very high resolution, sensitivity, and its unique ability to measure tissue concentrations of radioactivity in three dimensions, PET is the method of choice for in vivo imaging using therapeutic and diagnostic antibodies. Iodine-124 (124I) is a positron emitting radioisotope that can be attached to antibodies generally without significant loss of immunobiological characteristics; its 4.2-day half-life allows assessment of long-term pharmacokinetics of antibody forms (25-27). To the best of our knowledge, this report represents the first study of a positron-emitting form of a TEM1-directed antibody construct in a murine mouse model of human TEM1-expressing tumor vasculature.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies and Cell Lines

Humanized anti-hTEM1 MORAb-004 mAb (IgG1, 160 kDa), which binds human but not murine TEM1, was produced by Morphotek, Inc. (Exton, PA). The MS1 mouse endothelial cell line, engineered to express DsRed and firefly luciferase fLuc (for ease, designated as MS1), was used for subsequent generation of the MS1-TEM1 cell line, expressing human TEM1 (hTEM1), as well as EmGFP, in addition to DsRed and fLuc (18). MS1-TEM1 cells were sorted by flow-assisted flow cytometry sorting (FACS) using a MoFlo cell sorter (Dako Cytomation, Fort Collins, CO), and the cell population with lower hTEM1 expression were expanded and used for subsequent studies. ID8 is a mouse ovarian surface epithelium cancer cell line, provided by P. Terranova (University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS) (28). MS1 cell lines and the ID8 cell line were maintained in RPMI 1640 containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics. Full details of all methods and equipment used are presented in the supplemental materials (supplemental materials are available online only at http://jnm.snmjournals.org).

Radiolabeling

Iodination of MORAb-004 mAb and control IgG1 was performed by the Iodogen method (29). Briefly, 125I-NaI (in 0.01 N NaOH; Perkin Elmer, Boston, MA) or 124I-NaI (in 0.02 M NaOH; IBA Molecular, Dulles, VA) was added to a pre-coated iodination tube (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) containing antibody (15 μg, 1 mg/mL in phosphate buffered saline (PBS)), and incubated for 5 min. Radiolabeled antibody was purified using a 2-mL desalting column (Thermo Scientific). Trichloroacetic acid precipitation assay (30) and radioTLC was used to determine radiolabeling efficiency and purity for labeled antibodies. Protein concentration were measured using Nanodrop 2000c (Thermo Scientific) to calculate specific activity (MBq/mg).

In Vitro Characterization

Radioimmunoassay (RIA)

Assessment of specific binding of 125/124I-MORAb-004 was determined by RIA using cells grown to confluence on 1% gelatin-coated 96-strip well microplates (Corning Life Sciences, Lowell, MA). For direct mAb binding assay, cells were incubated with increasing concentration of 125/124I-MORAb-004 in assay buffer (5% FBS in RPMI 1040) in quadruplicate at 4°C for 4 h. Cells were washed five times with ice-cold wash buffer (3% bovine serum albumin (BSA)/PBS). Cell-associated radioactivity was measured by a gamma counter (2470 Wizard2, Perkin Elmer) and was normalized to the total number of cells, counted by hemocytometer. Non-specific binding (NSB) was determined using control MS1 cells, or by performing the assay in 100-fold excess of unlabeled ligand. RIA analysis was performed as previously described (30). The details to determine the apparent binding affinity, Kd, and the number of functional binding sites per cell, Bmax can found in the supplemental materials. In competitive binding assays, cells were incubated with a fixed concentration of 125/124I-mAb for 4 h at 4°C, in the presence of unlabeled MORAb-004 (0-200 nM). Binding data was collected as above, and the competitive binding data plotted as described in the supplemental materials.

Internalization Assay

For fluorescent ligand assay, cells were cultured on chamber-slides (Nunc; Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) overnight at 37°C in culture medium. Cells were incubated with DyLight405-MORAb-004 immunoconjugate (1 mL, 1.5 mg/mL in media) at 4°C and allowed to warm to 37°C for one hour. Following two 5-min washes with wash buffer (or additional glycine buffer wash (pH 2; 200 mM glycine; 150 mM NaCl)), cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Images were taken with an inverted LSM510 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY), employing 405 nm diode laser, 488 nm argon laser and 561 nm diode laser for excitation of Dylight405, EmGFP and DsRed respectively.

For radioligand assay, cells were grown to confluence on 1% gelatin-coated 96-strip well microplates, and incubated with 125I-MORAb-004 at 37°C at selected time points up to 24 h. Cells were placed on ice, and rinsed with wash buffer. Parallel plates were washed with glycine buffer (pH 2) twice for 5 min to remove surface bound radioactivity. Wells were counted in a gamma counter and normalized to total activity bound.

In Vivo Characterization

Chimeric Human TEM1-Expressing Murine Vascular Graft Model

All animal experiments were conducted in compliance with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines. Chimeric tumors expressing hTEM1 in the vasculature were established by subcutaneous injection of 2 × 106 ID8 cancer cells co-mixed with MS1-TEM1 or MS1 endothelial cells (at a ratio of 1:5 ID8 to MS1) in each mouse flank of female athymic nu/nu mice (Crl:NU-Foxn1nu, 18 g, 4-6 weeks, Charles River Laboratories, Inc. Wilmington, MA). Mice were provided with food and water ad libitum. Mice with tumor grafts expressing fLuc reporter were anesthetized with 1-2% isoflurance/O2 (VetEquip, Pleasanton, CA) and in vivo bioluminescence imaging (BLI) performed thrice weekly using the Xenogen IVIS Lumina II small animal imaging system (Caliper Life Science, Hopkinton, MA). Briefly, D-Luciferin (150 mg/mL PBS stock; 150 μL/15 g mouse) was injected intraperintoneally and optical images acquired 10 min post-injection (p.i.). Pseudocolor images of emitted photon radiance (p/s/cm2/sr) were generated and quantified with Living Image Version 3.0 software (Caliper Life Science). Tumors were allowed to grow to a size of 5-10 mm diameter (14-21 d), and then mice used for subsequent studies.

Biodistribution and Autoradiography Studies

Naïve mice and mice bearing ID8 tumors co-mixed with MS1 or MS1-TEM1 endothelial cells were administered 125I-MORAb-004 (0.185 MBq [5 μCi], 2.5 μg mAb, in 150 μL sterile 0.9% saline for injection) via the tail vein. Animals (n = 3–6, per group) were euthanized at 4, 24, 48, 72, and 144 h p.i., and organs and tumors were removed, weighed, and counted in a gamma counter for accumulation of activity. In a separate cohort, tumors were harvested, embedded in Tissue-TEK OCT compound (Sakura, Finetek U.S.A Inc.) and were frozen at −80 °C. Serial 10 μm-thick sections were cut at −20 °C in a cryostat (Leica CM1950). Sections were exposed to a phosphorimage plate (BAS, Fujifilm) for 48 h. Digital autoradiography (DAR) images were read using a phosphor plate reader (Typhoon FLA-7000, GE).

Immuno-PET Studies

PET experiments were conducted on a small animal A-PET scanner (Philips Mosaic) with an imaging field of view of 11.5 cm (31). Mice were administered 124I MORAb-004 (5.2 MBq [~140 μCi], 2.5 μg mAb, in 150 μL sterile 0.9% saline for injection) via tail vein injection. For blocking studies, mice were co-injected with 25 μg nonlabeled MORAb-004. Mice were anesthetized by inhalation of a 1-2% isoflurane/O2 and placed on the scanner bed prior to the imaging study. PET Data acquisition commenced at 4, 24, 48, and 72 h p.i. of radiotracer, and dynamic scans were carried out over a period of 1 h (5 min per frame; image voxel size 0.5 mm3). Analysis on reconstructed images was performed using AMIDE (http://amide.source-forge.net). After termination of the final PET scan, mice were euthanized and tissue activity assessed.

Data analysis and statistics

All experiments were performed at least in triplicate with a minimum of three independent experiments. Results are expressed as mean ± S.D. unless otherwise noted. Significant differences between means were determined using one-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc Bonferroni multiple comparison test, or unpaired student t-test, as appropriate. Differences at the 95% confidence level (P < 0.05) were considered statistically significant. All curve fitting and statistical analyses was conducted using Prism 5.0 software (Graphpad).

RESULTS

Radioiodination

MORAb-004 was successfully radiolabeled with near quantitative labeling efficiency. Radiochemical purity by radioTLC and TCA precipitation assays showed that > 98% of 125/124I was bound to protein post size-exclusion column purification (Supplemental Fig. 1). Specific activities for 125I-MORAb-004 ranged from 150-225 MBq/mg (4-6 mCi/mg; mean, 185 MBq/mg [5 mCi/mg]) and from 280-340 MBq/mg (7.6-9.2 mCi/mg) for IgG1 control (mean, 300 MBq/mg [8.1 mCi/mg]). For 124I-MORAb-004, specific activities were between 1920-2220 MBq/mg (52-60 mCi/mg; mean, 2072 MBq/mg [56 mCi/mg]).

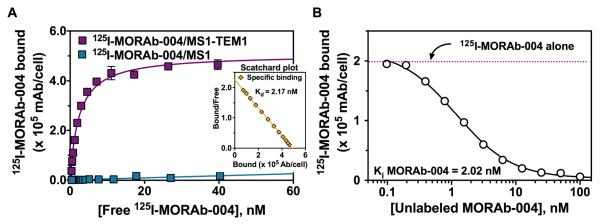

In Vitro Binding Properties of MORAb-004

The specificity of binding of 125I-MORAb-004 to human TEM1 was assessed with mouse endothelial MS1 cells engineered and subsequently sorted to express surface TEM1 as compared to control MS1 cells. The apparent dissociation constant (Kd) of 125I-MORAb-004 determined by live-cell RIA was 3.41 ± 1.20 nM, and the number of MORAb-004 mAb bound per cell (Bmax) was 6.28 ± 2.14 × 105 (Fig. 1A). 125I-MORAb-004 did not bind to control MS1 cells, and binding on MS1-TEM1 cells could be blocked with excess unlabeled mAb, demonstrating specificity. Competitive binding assays demonstrated that 125I-MORAb-004 was displaced with increasing amounts of unlabeled MORAb-004, with Ki of unlabeled MORAb-004 being 3.10 ± 1.24 nM (Fig. 1B). MAb immunoreactivity from RIA was approximately 90% for both 125I-MORAb-004 and 124I-MORAb-004 following direct iodination at the noted specific activity (Table 1). 125IMORAb-004 bound to endogenous hTEM1 with higher affinity (Kd ~0.5 nM) when incubated with human neuroblastoma LA1-5s cells, as compared to recombinant hTEM1 expressed in the murine MS1-TEM1 cell line (Supplemental Fig. 2). The number of surface hTEM1 molecules is comparable between LA1-5s cells and MS1-TEM1 cells.

FIGURE 1.

Cell surface binding parameters of 125I-MORAb-004 to MS1-TEM1 and MS1 cells by live-cell RIA. (A) Saturation binding curve for 125I-MORAb-004 from a representative experiment at 4°C for 4 h (the inset shows the Scatchard plot). (B) Competitive binding of 125I MORAb-004 (5.0 nM) with increasing concentrations of unlabeled MORAb-004. Binding data were plotted as 125I-MORAb-004 bound per cell (mAb/cell).

TABLE 1.

Binding Parameters of antiTEM1 IgG1 MORAb-004 mAb to Live MS1 Cells Expressing hTEM1*

| mAb | Specific Activity (MBq/mg) |

Kd (nM) | Bmax (× 105 mAb / cell) |

IR† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

125I-MORAb-004 (n = 5) |

150-225 | 3.41 ± 1.20 | 6.28 ± 2.14 | 90.1 ± 4.8% |

|

124I-MORAb-004 (n = 3) |

1920-2220 | 3.41 ± 0.93 | 7.52 ± 1.92 | 90.1 ± 1.5% |

MS1 cells used as binding control; results expressed as mean ± S.D.

Immunoreactivity (IR) = Kd 125/124I-MORAb-004/Ki unlabeled MORAb-004

Internalization of MORAb-004

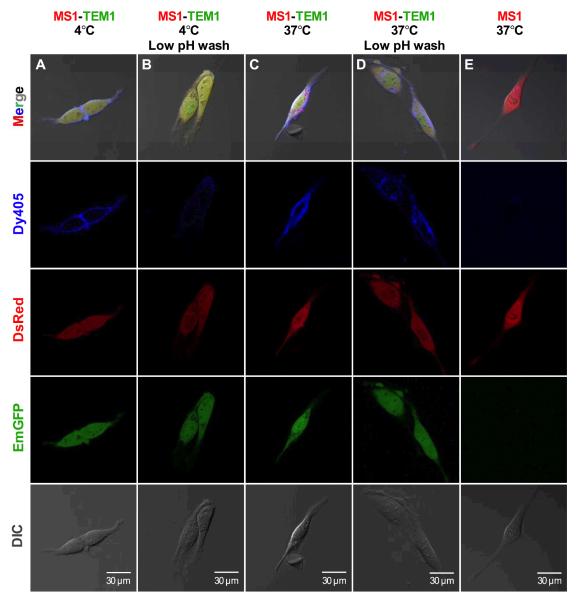

To qualitatively assess mAb MORAb-004 internalization following binding to TEM1, we followed the location of fluorescent dye-labeled MORAb-004 (MORAb-004-Dy405) on MS1-TEM1 cells vs. control MS1 cells by confocal microscopy. Cells were initially incubated with MORAb-004-Dy405 on ice and then allowed to warm to 37°C. At 4°C MORAb-004-Dy405 (blue) localized to the cell membrane on MS1-TEM1 cells (Fig. 2A), but there was no binding on MS1 cells (Fig. 2E). Surface binding could be effectively removed following acid wash, showing that signal was restricted to the plasma membrane at 4°C (Fig. 2B). Following warming to 37°C for one hour, strong immunofluorescence was observed on both plasma membrane and in intracellular compartments of MS1-TEM1 cells (Fig. 2C). Internalization of MORAb-004-Dy405 was confirmed by acid wash of MS1-TEM1 cells, where surface-bound mAb was removed, but intracellular MORAb-004-Dy405 was still retained (Fig. 2D).

FIGURE 2.

Confocal immunofluorescence microscopy of MS1-TEM1 (A-D) and MS1 (E) cells incubated with fluorescent immunoconjugate MORAb-004-DyLight405 (Dy405; blue) show that MORAb-004 is internalized in MS1-TEM1 cells. MS1-TEM1 cells were transfected with DsRed (red) and GFP (green), whereas MS1 cells express only DsRed (Red). MORAb-004-Dy405 localized to cell surface membrane of MS1-TEM1 cells at 4°C for 1 h (A), and it could be effectively removed following low pH wash (B). After 1 h at 37°C, MORAb-004 was observed on the cells surface and in intracellular compartments of MS1-TEM1 cells (C), with the intracellular fraction still evident following low pH wash (D). MORAb-004 did not bind to MS1 cells (E). Merging of the blue, red, and green channel with the phase contrast (DIC) image is shown in the first panel A-E. Scale bar in DIC panel is 30 μm.

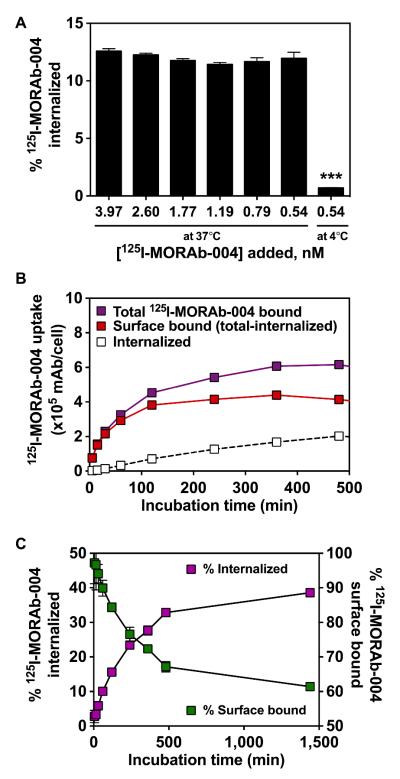

For quantitative assessment of MORAb-004 internalization, MS1-TEM1 cells were incubated with 125I-MORAb-004 and the internalization of MORAb-004 was studied by gamma counting (Fig. 3). The fraction of radioactivity that internalized in MS1-TEM1 cells at 2 h at 37°C was ~12% of total activity bound, and it did not change with increasing dose of 125I-mAb added to the media (0.5-4 nM) (Fig. 3A). The fraction of radioactivity that internalized in MS1-TEM1 cells, with respect to the total amount of 125I-MORAb-004 bound per MS1-TEM1 cell, increased from 15.6 ± 0.7% at 2 h to 23.4 ± 0.9% at 4 h, and reached a plateau at 8 h from 32.8 ± 0.8% to 38.6 ± 0.9% at 24 h (Fig. 3B,C). Interestingly, in LA1-5s neuroblastoma cells, which endogenously express hTEM1, maximum internalization was achieved at 60 min and remained quite low at < 10% at all time points thereafter (Supplemental Fig. 3). The uptake of radioactivity was completely blocked by the addition of unlabeled MORAb-004 to the incubation media, thus demonstrating the requirement of TEM1-specific binding in mediating internalization. Figure 3B and 3C shows the internalized and surface bound fractions over time, with respect to total cell bound radioactivity. The surface bound fraction of radioactivity was the activity removed from the total bound activity following an acid wash of the cells.

FIGURE 3.

Internalization of 125I-MORAb-004 by MS1-TEM1/fLuc cells with respect to the total amount of mAb bound per cell following incubation at 37°C as a function of dose (A) and time (B-C). Internalization was measured in presence or absence of an excess of unlabeled MORAb-004 (100 nM) in incubation medium to block hTEM1 surface protein binding. (C) Internalized fraction of 125I-MORAb-004 over time as a function of total cell-associated radioactivity. Values shown are mean of three independent experiments performed in quadruplicate. ***, P-value < 0.001.

In Vivo Characterization

Biodistribution Studies

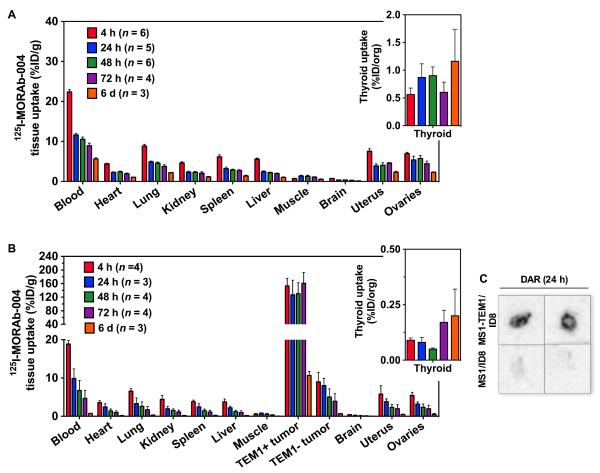

In naïve non-tumor bearing mice there was a dramatic difference in the blood clearance kinetics of 125I-MORAb-004, as compared to mice bearing ID8 tumor grafts enriched with MS1 or MS1-TEM1 endothelial cells in either flank (Fig. 4 and Tables 2 and 3). In naïve mice, the blood pool activity was 22.39 ± 1.47 %ID/g at 4 h and slowly decreased 4-fold to 5.64 ± 0.50 %ID/g on day 6. Blood-pool activity decreased 25-fold over a 6-day period, from 18.84 ± 0.93 %ID/g at 4 h to 0.74 ± 0.05 % ID/g on day 6. There was slower washout of activity across all major organs, as seen with blood levels, in naïve mice, as compared to tumor-bearing mice. In contrast, uptake in TEM1-postive tumor grafts (TEM1+) was 153.19 ± 22.24 %ID/g as early as 4 h p.i. and remained consistently high out to 3 d p.i., demonstrating retention of the TEM1-targeted antibody. Uptake in TEM1+ tumors decreased to 10.65 ± 1.08 %ID/g at 6 d p.i. Uptake in TEM1-negative tumor grafts (TEM1-) was significantly lower than TEM1+ tumors at all time points, with uptake clearing over time from 8.98 ± 2.48 % ID/g at 4 hours to 3.93 ± 1.98 %ID/g at 72 h, and 0.67 ± 0.08 %ID/g on day 6. Autoradiography of tumors at 24 h p.i. further confirmed higher uptake of 125I-MORAb-004 in TEM1+ tumors than in the control tumors (Fig. 4C). The tumor-to-blood ratio in TEM1+ grafts increased 4.5-fold from 8.1 to a maximum of 40.6 on day 3. Similarly, the TEM1+:TEM1- tumor ratio in ID8 grafts increased 2.7-fold from 18.1 to a maximum of 49.1 on day 3. Target to non-target uptake ratios were decreased by day 6. As an indication of radioiodine metabolism from the antibody, thyroid uptake was also assessed over time. No time-dependent changes in thyroid uptake were observed in both naïve and tumor-bearing mice up to 6 days p.i. Thyroid levels ranged from 0.1 to 1.2 %ID per total organ.

FIGURE 4.

Biodistribution (%ID/g) of 125I-MORAb-004 (2.5 μg/mouse) in (A) naïve nu/nu female mice and (B) MS1-TEM1/ID8 and MS1/ID8 tumor bearing mice. Insets are respective uptake of radioiodine in thyroid represented as %ID/organ. Data are shown as mean ± S.D. There was a significant difference between uptake in TEM1+ tumors as compared to TEM1- tumors. P- value < 0.001. (C) Digital autoradiography (DAR) of representative MS1-TEM1/ID8 and control MS1/ID8 tumors showing specific uptake of 125I-MORAb-004 24 h after injection in TEM1+ tumors only.

TABLE 2.

Biodistribution of 125I-MORAb-004 in Naïve Mice at Various Times After Injection*

| Organ | 4 h (n = 6) | 24 h (n = 5) | 48 h (n = 6) | 72 h (n = 4) | 6 d (n = 4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood | 22.39 ± 1.47 | 11.64 ± 0.95 | 10.53 ± 1.32 | 8.93 ± 1.30 | 5.64 ± 0.50 |

| Heart | 4.40 ± 0.38 | 2.26 ± 0.32 | 2.40 ± 0.52 | 1.94 ± 0.30 | 1.06 ± 0.10 |

| Lungs | 8.85 ± 1.06 | 4.88 ± 0.47 | 4.58 ± 0.66 | 3.76 ± 0.80 | 2.20 ± 0.15 |

| Kidney | 4.61 ± 0.69 | 2.32 ± 0.57 | 2.28 ± 0.62 | 2.06 ± 0.69 | 1.14 ± 0.27 |

| Spleen | 6.17 ± 1.20 | 3.20 ± 0.84 | 2.88 ± 0.46 | 2.71 ± 0.42 | 1.40 ± 0.29 |

| Liver | 5.56 ± 0.71 | 2.41 ± 0.57 | 2.21 ± 0.31 | 2.00 ± 0.22 | 1.03 ± 0.22 |

| Muscle | 0.69 ± 0.31 | 1.36 ± 0.44 | 1.28 ± 0.69 | 1.11 ± 0.18 | 0.55 ± 0.18 |

| Brain | 0.77 ± 0.11 | 0.37 ± 0.08 | 0.40 ± 0.09 | 0.29 ± 0.09 | 0.18 ± 0.01 |

| Uterus | 7.55 ± 1.54 | 3.86 ± 1.16 | 4.06 ± 1.49 | 4.57 ± 0.31 | 2.30 ± 0.47 |

| Ovaries | 6.98 ± 0.75 | 5.36 ± 2.18 | 5.75 ± 1.81 | 4.42 ± 1.31 | 2.30 ± 0.18 |

| Thyroid† | 0.56 ± 0.29 | 0.87 ± 0.55 | 0.90 ± 0.39 | 0.60 ± 0.37 | 1.16 ± 0.99 |

Data are expressed as %ID/g ± S.D.; mice injected with 0.185 MBq [5 μCi]; 2.5 μg IgG

Data are expressed as %ID/Org ± S.D.

TABLE 3.

Biodistribution of 125I-MORAb-004 in Tumor-Bearing Mice at Various Times After Injection*

| Organ | 4 h (n = 3) | 24 h (n = 3) | 48 h (n = 4) | 72 h (n = 4) | 6 d (n = 3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood | 18.84 ± 0.93 | 9.90 ± 2.49 | 6.75 ± 2.61 | 4.68 ± 2.09 | 0.74 ± 0.05 |

| Heart | 3.55 ± 0.51 | 2.48 ± 0.81 | 1.40 ± 0.53 | 1.00 ± 0.44 | 0.18 ± 0.04 |

| Lungs | 6.57 ± 0.71 | 3.32 ± 1.48 | 2.62 ± 1.16 | 1.75 ± 0.82 | 0.33 ± 0.02 |

| Kidney | 4.46 ± 0.98 | 1.98 ± 0.64 | 1.54 ± 0.41 | 1.13 ± 0.52 | 0.21 ± 0.04 |

| Spleen | 3.81 ± 0.43 | 2.47 ± 0.83 | 1.45 ± 0.46 | 1.10 ± 0.49 | 0.23 ± 0.08 |

| Liver | 3.76 ± 0.76 | 2.23 ± 0.43 | 1.19 ± 0.42 | 0.99 ± 0.45 | 0.19 ± 0.02 |

| Muscle | 0.58 ± 0.16 | 0.77 ± 0.15 | 0.58 ± 0.13 | 0.47 ± 0.29 | 0.06 ± 0.01 |

| Brain | 0.40 ± 0.06 | 0.25 ± 0.11 | 0.15 ± 0.07 | 0.12 ± 0.05 | 0.03 ± 0.01 |

| Uterus | 5.77 ± 2.25 | 3.79 ± 0.76 | 2.33 ± 0.82 | 2.00 ± 1.04 | 0.47 ± 0.12 |

| Ovaries | 5.44 ± 0.82 | 3.20 ± 0.56 | 2.37 ± 0.85 | 2.01 ± 0.87 | 0.51 ± 0.24 |

| Thyroid† | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 0.08 ± 0.04 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.17 ± 0.11 | 0.20 ± 0.17 |

| Tumors | |||||

| MS1-TEM1/ID8 | 153.19 ± 22.25 | 127.13 ± 42.87 | 130.27 ± 32.38 | 160.91 ± 32.09 | 10.65 ± 1.08 |

| MS1/ID8 | 8.98 ± 2.48 | 8.03 ± 1.86 | 5.04 ± 2.12 | 3.93 ± 1.98 | 0.67 ± 0.08 |

| Ratio of TEM1+ Tumor to: | |||||

| Blood | 8.14 ± 1.13 | 12.36 ± 4.72 | 21.76 ± 9.15 | 40.64 ± 19.40 | 16.50 ± 3.68 |

| Muscle | 266.03 ± 84.62 | 164.35 ± 64.30 | 224.86 ± 74.10 | 340.03 ± 216.28 | 177.50 ± 34.63 |

| TEM1- Tumor | 18.06 ± 5.10 | 16.51 ± 6.21 | 29.71 ± 13.29 | 49.14 ± 22.54 | 16.02 ± 2.51 |

Data are expressed as %ID/g ± S.D.; mice injected with 0.185 MBq [5 μCi]; 2.5 μg IgG

Data are expressed as %ID/Org ± S.D.

The specificity of TEM1 tumor targeting was demonstrated using an isotype control IgG1. The biodistribution of 125I-IgG1 shows that uptake of the nontargeted IgG is nearly the same between both MS1-TEM1 and MS1 vascularized tumors, with 5.43 ± 0.73 %ID/g and 5.13 ± 1.86 %ID/g at 24 h p.i, respectively (see supplemental materials). The localization ratio of TEM1+ tumor uptake to blood, and TEM1- tumor uptake were low for nontargeted IgG1 (generally <1), indicating a lack of specific uptake.

Pharmacokinetic Analysis

To evaluate the blood pharmacokinetics of 125I-MORAb-004 in naïve versus TEM1-positive tumor-bearing nu/nu mice, serum samples were collected and analyzed at defined times (see supplemental information). Blood pool clearance rates were very slow for the targeted IgG1 mAb in naïve mice as compared to mice with TEM1+ tumor: the fast α-phase of the biphasic blood clearance was 1.9 versus 1.1 hours, respectively, whereas the slower β-phase was 117.9 hours in naïve mice compared to 28.8 hours in tumor-bearing mice (R2 0.95 and 0.92, respectively). For further comparison, the α- and β-decay rates for blood clearance of the isotype control 125I-IgG1 in tumor-bearing mice were 3.7 h and 76.9 h, respectively. These rates were both slower than those for 125I-MORAb-004 in tumor-bearing mice, further demonstrating targeting specificity of 125I-MORAb-004 for TEM1-positive tumors.

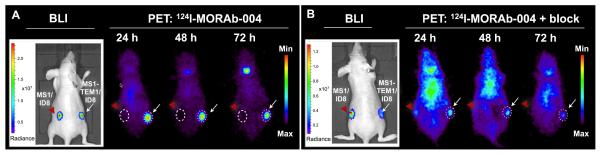

PET Imaging Studies

Tumor location and volume was first confirmed by in vivo BLI of fLuc reporter gene expression in mice bearing s.c ID8 tumor graft with MS1-TEM1-expressing vasculature on left flank and control MS1/ID8 tumor graft on right flank. 124I-MORAb-004 uptake in tumor grafts was TEM1-specific, as demonstrated by target-blocking experiments performed by co-injecting an excess dose (25 μg) of nonlabeled cold MORAb-004 (Fig. 5B). TEM1+ tumors were poorly visualized throughout the three-day study period, demonstrating TEM1-specificity of MORAb-004. Images for the remaining mice in the PET study are provided in the supplemental materials. Postmortem tissue sampling of the mice following 72 h PET imaging confirmed the biodistribution data. The tumor uptake of 124I-MORAb-004 was 221.82 ± 57.33 %ID/g in TEM1+ tumor grafts at 72 hours p.i. and was significantly greater than corresponding tumor uptake of 24.06 ± 3.26 %ID/g at 72 hours in mice blocked with excess cold MORAb-004, again confirming radioimmunoconjugate specificity (see supplemental information). In contrast, no significant difference in tumor uptake was observed in TEM1-tumor grafts following co-injected with blocking dose of MORAb-004 (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

Longitudinal in vivo immuno-PET imaging of distribution of 124I-MORAb-004 in nude mice bearing subcutaneous chimeric ID8 tumor grafts over time. Mice were injected with 124I-MORAb-004 (5.2 MBq, 2.5 μg mAb) (A) or co-injected with 25 μg of unlabeled MORAb- 004 (B) and scanned for 1 h at different time points post-injection. Transverse projections from one mouse from each group in shown, with representative images of photon radiance from BLI of tumor grafts enriched with luciferase (fLuc)-transfected MS1 or MS1-TEM1 endothelial cells of respective mouse is shown to the left of each PET panel. (A) Increased uptake of 124I MORAb-004 was observed in tumors expressing TEM1+ tumor (right, white arrow), compared with control tumor (left, red arrowhead). (B) Specific blocking of 124I-MORAb-004 uptake in TEM1+ tumor observed following administration of excess unlabeled mAb.

DISCUSSION

The tumor vascular marker TEM1/endosialin is emerging as an attractive biomarker for targeted molecular diagnostics and therapeutics due to its expression across many human tumors, low to absent expression in normal tissues, and accessibility from the vascular circulation. While the molecular function of TEM1 remains unclear, investigators have recently designed IgG antibodies targeting the lectin-like domain of TEM1, which inhibit cell migration (20) and vascular tube formation (9, 32, 33). Smaller scFv constructs have also been reported for TEM1-targeting of drug delivery vehicles (19), or diagnostics for fluorescence imaging techniques (17). Although TEM1 is a quasi-universal tumor target present in the vasculature of many solid tumor types, a variable proportion of tumors– depending on histotype– show low or no TEM-1 expression (6). Detection of TEM1 in tumors may facilitate the selection of patients for specific therapies and would allow monitoring of therapeutic effect in real time using immuno-PET (25, 34, 35). Combined with the ready availability of 124I and its sufficiently long t1/2 (4.2 d), 124I-immuno-PET imaging is an attractive approach to demonstrate quantitative biomarker expression non-invasively. In this work, we describe the detailed pre-clinical characterization of a novel PET radioimmunodiagnostic humanized anti-TEM1 124I-MORAb-004 IgG1, of which the naked antibody MORAb-004 is currently in trials for cancer immunotherapy.

Direct radioiodination of MORAb-004 did not dramatically alter the functional targeting to MS1 mouse endothelial cells engineered to express recombinant hTEM1 (MS1-TEM1), as evidenced by the nM affinity, high cellular binding capacity (>105 antibodies bound per cell), and immunoreactivity of 125/124I-MORAb-004. Differences in degree and quality of hTEM1 glycosylation patterns in murine and human cells could potentially overestimate MORAb-004 accessibility and binding to native human TEM1. However, the affinity of 125I-MORAb-004 for native hTEM1 expressed in human neuroblastoma cancer cells is considerably higher than recombinant hTEM1 in murine endothelial cells. This would suggest that MORAb-004 accessibility and affinity is sufficiently high for targeting to endogenous hTEM1 in patients in vivo. Antibody internalization and intracellular retention are important criteria for assessing the potential of a therapeutic agent being considered for conjugation with a toxin or radioisotope. Fluorescence microscopy of dye-labeled MORAb-004 and radiotracing of 125I-MORAb-004 confirm slow internalization (and radiolabel catabolism ex post facto) in vitro by MS1-TEM1 endothelial cells. Internalization was found to be even slower in human neuroblastoma cells endogenously expressing hTEM1. However, in vitro results may not always be indicative of Ab processing in vivo.

MORAb-004 binds to human TEM1 and does not cross-react with murine TEM1. Hence, we used a chimeric ovarian cancer vascular murine model recently described to assess the targeting of MORAb-004 to human TEM1 TVM (18). In this preclinical model, tumors derived from ID8 ovarian cancer cells enriched with MS1 endothelial cells had increased vascular density compared to ID8 tumors alone by visual inspection and from quantification of hemoglobin content (data not shown). This implies that MS1 cells contribute to the formation of functional tumor vasculature. Further, MS1-TEM1 cells admixed with ID8 cells integrate into the tumor vasculature, as confirmed by IHC visualization of hTEM1-positive vessels and capillaries (Supplemental Fig. 8).

Biodistribution data with this vascular hTEM1 murine model revealed high uptake of 125IMORAb-004 (>150 %ID/g at 4 h) in ID8 ovarian tumors with TEM1-positive tumor vasculature and no uptake in the contralateral hTEM1-negative ID8/MS1 tumors. This high degree of targeting to TEM1-positive vessels was maintained up to 72 hours p.i., with target tumor uptake decreasing on day 6. There was a low extent of thyroid uptake over the course of the biodistribution and PET study (< 2 %ID/org). This is consistent with previously reported studies with other radioiodine-labeled mAbs targeting slowly internalizing cell surface markers—including 124I-cG250 IgG mAb for imaging CAIX expression (25), and 125I-35A7 IgG mAb, as a radioimmunotherapeutic targeted to CEA (36). Therefore, we can tentatively conclude that the Ab catabolic rate in vivo is comparable to that seen in vitro. It is plausible that slow intratumoral metabolism and subsequent re-circulation of 124I-labeled metabolites may also occur. Full metabolic studies are beyond the scope of the current study and will be the subject of further investigations.

This type of preclinical model is a helpful tool for validating agents specific to human tumor vascular targets in the absence of more relevant knock-in models with the human coding sequence inserted into the mouse locus. Immuno-PET data demonstrate that 124I-MORAb-004 imaging provides high tumor–to–background tissue ratios and that this high uptake is specific for TEM1 expression in tumor tissue. On the basis of the aforementioned in vivo results, 124I MORAb-004 has favorable pharmacokinetics, with rapid tumor targeting, rapid blood clearance, and fast washout from non-target tissue. An experimental limitation to our preclinical model is that hTEM1 is exclusively expressed on engineered murine endothelial cells that integrate into the murine tumor vasculature and so we are only able to assess targeting and tumor retention of MORAb-004 to the most easily accessible tumor vascular compartment. In human tumors, TEM1 is expressed by tumor-associated stromal cells, fibroblasts, and pericytes (7, 37, 38), various types of cancer cells, as well as endothelial progenitor cells (6, 33). However, IgG can readily cross the leaky basement membrane of tumor vasculature and extravasate into the perivascular space, suggesting that MORAb-004 could bind readily to various cell types presenting surface TEM1 in the tumor microenvironment. While this model cannot address questions including the temporal regulation of hTEM1 with respect to tumor size or upon internalization of the antibody, the recent development of a hTEM1 knock-in mice (39) will allow future studies to focus towards that goal.

Overall, the novel radiotracer 124I-MORAb-004 represents a promising candidate for further evaluation and translation to the clinic as an immuno-PET agent for the noninvasive detection of primary and metastatic cancers expressing TEM1 in vivo.

CONCLUSION

The humanized antihTEM1 IgG mAb 125/124I-MORAb-004 can be prepared by direct radioiodination, with high radiochemical purity and specific activity, without significant loss of specificity and immunoreactivity to hTEM1-positive cells. In vitro internalization is fairly low and protracted. Biodistribution and 124I-immuno-PET in a chimeric hTEM1 mouse tumor model revealed robust TEM1-specific contrast within the tumor vasculature as early as 4 hours and up to 6 days post-administration. Autoradiography further confirmed microdistribution of 124I MORAb-004 within TEM1-postitive vascularized tumor tissue. This is the first report fully characterizing 124I-MORAb-004 as an immune-PET diagnostic of noninvasive detection of human TEM1 in a murine tumor vascular network.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by NIH transformative R01CA156695; the Honorable Tina Brozman Foundation and a grant from the Basser Center at the University of Pennsylvania. We thank Eric Blankemeyer of the University of Pennsylvania Small Animal Imaging Facility (SAIF) for excellent technical support.

REFERENCES

- 1.St Croix B, Rago C, Velculescu V, et al. Genes expressed in human tumor endothelium. Science. 2000;289:1197–1202. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5482.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carson-Walter EB, Watkins DN, Nanda A, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW, St Croix B. Cell surface tumor endothelial markers are conserved in mice and humans. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6649–6655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buckanovich RJ, Sasaroli D, O’Brien-Jenkins A, et al. Tumor vascular proteins as biomarkers in ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:852–861. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.8583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rettig WJ, Garin-Chesa P, Healey JH, Su SL, Jaffe EA, Old LJ. Identification of endosialin, a cell surface glycoprotein of vascular endothelial cells in human cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:10832–10836. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christian S, Ahorn H, Koehler A, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of endosialin, a C-type lectin-like cell surface receptor of tumor endothelium. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:7408–7414. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009604200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rouleau C, Curiel M, Weber W, et al. Endosialin protein expression and therapeutic target potential in human solid tumors: sarcoma versus carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:7223–7236. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simonavicius N, Robertson D, Bax DA, Jones C, Huijbers IJ, Isacke CM. Endosialin (CD248) is a marker of tumor-associated pericytes in high-grade glioma. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:308–315. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3801006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christian S, Winkler R, Helfrich I, et al. Endosialin (Tem1) is a marker of tumor-associated myofibroblasts and tumor vessel-associated mural cells. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:486–494. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bagley RG. Endosialin: from vascular target to biomarker for human sarcomas. Biomark Med. 2009;3:589–604. doi: 10.2217/bmm.09.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies G, Cunnick GH, Mansel RE, Mason MD, Jiang WG. Levels of expression of endothelial markers specific to tumour-associated endothelial cells and their correlation with prognosis in patients with breast cancer. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2004;21:31–37. doi: 10.1023/b:clin.0000017168.83616.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teicher BA. Newer vascular targets: endosialin (review) Int J Oncol. 2007;30:305–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valdez Y, Maia M, Conway EM. CD248: reviewing its role in health and disease. Current drug targets. 2012;13:432–439. doi: 10.2174/138945012799424615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carson-Walter EB, Winans BN, Whiteman MC, et al. Characterization of TEM1/endosialin in human and murine brain tumors. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:417. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rmali KA, Puntis MC, Jiang WG. Prognostic values of tumor endothelial markers in patients with colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:1283–1286. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i9.1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dolznig H, Schweifer N, Puri C, et al. Characterization of cancer stroma markers: in silico analysis of an mRNA expression database for fibroblast activation protein and endosialin. Cancer Immun. 2005;5:10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Opavsky R, Haviernik P, Jurkovicova D, et al. Molecular characterization of the mouse Tem1/endosialin gene regulated by cell density in vitro and expressed in normal tissues in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38795–38807. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105241200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao A, Nunez-Cruz S, Li C, Coukos G, Siegel DL, Scholler N. Rapid isolation of high-affinity human antibodies against the tumor vascular marker Endosialin/TEM1, using a paired yeast-display/secretory scFv library platform. J Immunol Methods. 2011;363:221–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li C, Swails JL, Hasegawa K, et al. In vivo modeling and detection of the ovarian cancer vascular marker TEM1. Paper presented at: American Association for Cancer Research (AACR): Third International Conference on Molecular Diagnostics in Cancer Therapeutic Development; Philadelphia, PA, United States. Sept 22-25, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marty C, Langer-Machova Z, Sigrist S, Schott H, Schwendener RA, Ballmer-Hofer K. Isolation and characterization of a scFv antibody specific for tumor endothelial marker 1 (TEM1), a new reagent for targeted tumor therapy. Cancer Lett. 2006;235:298–308. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tomkowicz B, Rybinski K, Foley B, et al. Interaction of endosialin/TEM1 with extracellular matrix proteins mediates cell adhesion and migration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:17965–17970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705647104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.ClinicalTrials.gov [Accessed June 30, 2013];Sarcoma Study of MORAb-004 Utilization: Research and Clinical Evaluation. (SOURCE) 2013 Mar 5; http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01574716.

- 22.Becker R, Lenter MC, Vollkommer T, et al. Tumor stroma marker endosialin (Tem1) is a binding partner of metastasis-related protein Mac-2 BP/90K. Faseb J. 2008;22:3059–3067. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-101386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brady J, Neal J, Sadakar N, Gasque P. Human endosialin (tumor endothelial marker 1) is abundantly expressed in highly malignant and invasive brain tumors. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2004;63:1274–1283. doi: 10.1093/jnen/63.12.1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacFadyen JR, Haworth O, Roberston D, et al. Endosialin (TEM1, CD248) is a marker of stromal fibroblasts and is not selectively expressed on tumour endothelium. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:2569–2575. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Divgi CR, Pandit-Taskar N, Jungbluth AA, et al. Preoperative characterisation of clear-cell renal carcinoma using iodine-124-labelled antibody chimeric G250 (124I-cG250) and PET in patients with renal masses: a phase I trial. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:304–310. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70044-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kenanova V, Olafsen T, Crow DM, et al. Tailoring the pharmacokinetics and positron emission tomography imaging properties of anti-carcinoembryonic antigen single-chain Fv-Fc antibody fragments. Cancer Res. 2005;65:622–631. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sundaresan G, Yazaki PJ, Shively JE, et al. 124I-labeled engineered anti-CEA minibodies and diabodies allow high-contrast, antigen-specific small-animal PET imaging of xenografts in athymic mice. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:1962–1969. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams SR, Son DS, Terranova PF. Protein kinase C delta is activated in mouse ovarian surface epithelial cancer cells by 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) Toxicology. 2004;195:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bailey G. The Iodogen method for radiolabeling protein. In: Walker JM, editor. The Protein Protocols Handbook. Humana Press, Inc.; Totowa, New Jersey: 1996. pp. 673–674. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chacko AM, Nayak M, Greineder CF, Delisser HM, Muzykantov VR. Collaborative enhancement of antibody binding to distinct PECAM-1 epitopes modulates endothelial targeting. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34958. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Surti S, Karp JS, Perkins AE, et al. Imaging performance of A-PET: a small animal PET camera. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2005;24:844–852. doi: 10.1109/tmi.2005.844078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bagley RG, Honma N, Weber W, et al. Endosialin/TEM 1/CD248 is a pericyte marker of embryonic and tumor neovascularization. Microvasc Res. 2008;76:180–188. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bagley RG, Rouleau C, St Martin T, et al. Human endothelial precursor cells express tumor endothelial marker 1/endosialin/CD248. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:2536–2546. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pryma DA, O’Donoghue JA, Humm JL, et al. Correlation of in vivo and in vitro measures of carbonic anhydrase IX antigen expression in renal masses using antibody 124I-cG250. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:535–540. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.083295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Donoghue JA, Smith-Jones PM, Humm JL, et al. 124I-huA33 antibody uptake is driven by A33 antigen concentration in tissues from colorectal cancer patients imaged by immuno-PET. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:1878–1885. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.095596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Santoro L, Boutaleb S, Garambois V, et al. Noninternalizing monoclonal antibodies are suitable candidates for 125I radioimmunotherapy of small-volume peritoneal carcinomatosis. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:2033–2041. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.066993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wesseling P, Schlingemann RO, Rietveld FJ, Link M, Burger PC, Ruiter DJ. Early and extensive contribution of pericytes/vascular smooth muscle cells to microvascular proliferation in glioblastoma multiforme: an immuno-light and immuno-electron microscopic study. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1995;54:304–310. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199505000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.MacFadyen JR, Haworth O, Roberston D, et al. Endosialin (TEM1, CD248) is a marker of stromal fibroblasts and is not selectively expressed on tumour endothelium. FEBS Letters. 2005;579:2569–2575. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krauthauser C, Grasso L, Nicolaides NC, Lin JM. Neutralizing Endosialin antibody, MORAb-004, enhances efficacy of TAXOTERE in a metastatic melanoma model. Proceedings of the 103rd Annual Meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research; Chicago, IL, United States. AACR; 2012. Abstract nr 4410. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.