Abstract

Purpose

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is one of the leading causes of cancer death. No effective therapy is currently available for PDAC because of the lack of understanding of the mechanisms leading to its growth and development. Inflammatory cells, particularly mast cells have been shown to play key roles in some cancers. We carried out this study to test the hypothesis that mast cells in the tumor microenvironment are essential for PDAC tumorigenesis.

Experimental Design

The presence of inflammatory cells at various stages of PDAC development was determined in a spontaneous mouse model of PDAC (K-rasG12V). The importance of mast cells was determined using orthotopically implanted PDAC cells in mast cell-deficient Kitw-sh/w-sh mice and further confirmed by reconstitution of wild-type bone marrow-derived mast cells. Clinical relevance was assessed by correlating the presence of mast cells with clinical outcome in patients with PDAC.

Results

In the spontaneous mouse model of PDAC (K-rasG12V), there was an early influx of mast cells to the tumor microenvironment. PDAC tumor growth was in mast cell-deficient Kitw-sh/w-sh mice, but aggressive PDAC growth was restored when PDAC cells were injected into mast cell-deficient mice reconstituted with wild-type bone marrow-derived mast cells. Mast cell infiltration into the tumor microenvironment was predictive of poor prognosis in patients with PDAC.

Conclusions

Mast cells play an important role in PDAC growth and development in mouse models and are indicative of poor prognosis in humans, which makes them a potential novel therapeutic target.

Keywords: Pancreatic cancer, mast cell, inflammation

Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), whose nomenclature derives from its histologic resemblance to ductal cells, is the most common pancreatic malignancy, and an estimated 213,000 new cases are diagnosed worldwide annually (1). It is the fourth-leading cause of cancer death in the United States, with very dismal survival rates. Median survival duration after diagnosis is 3–6 months and the 5-year survival rate is less than 5%, which is the lowest survival rate of all cancer types (1). Moreover, this cancer is notoriously resistant to all conventional treatment modalities, including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and even modern targeted therapies. The lack of effective treatment results from a poor understanding of PDAC tumor biology. Therefore, a better understanding of PDAC’s aggressive characteristics and tumorigenesis is needed before treatment advances can be made.

Recently, inflammation and other tumor microenvironment characteristics have drawn attention as central factors in the tumorigenesis of many cancers. The association between inflammation and PDAC development has been known for years (2, 3) and was recently validated in an animal model (4). Throughout the process of tumorigenesis, disease progression, and metastasis, the microenvironment of the local host tissue is an active participant and determines the extent of cancer cell proliferation, angiogenesis, invasion, and survival (5, 6). Treatments that target both the cancer and its surrounding microenvironment may provide the best approach (7, 8). This approach is particularly useful in PDAC, which is characterized by a dense tumor stroma that contains a cell-rich population, including stellate cells, fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, dendritic cells, macrophages, and other inflammatory cells. Tumor cells can release chemotactic factors that induce inflammatory cell infiltration. In turn, inflammatory cells can produce cytokines and growth factors that can directly enhance tumor growth or act on stromal cells or the extracellular matrix to release additional tumorigenic factors (8). The presence of these immune regulatory cells in the tumor stroma contributes significantly to the immunosuppressive microenvironment (9) that promotes tumorigenesis.

One type of these inflammatory cells, mast cells, has begun to receive attention for its role in human malignancy. Mast cells regulate adaptive immune responses via the release of cytokines and other immunomodulatory factors (10–12). These factors can promote immune suppression and may contribute to PDAC progression. The important roles of mast cells have been reported in many human malignancies (13–17). However, the role of mast cells in human PDAC remains obscure.

We hypothesize that mast cells in the tumor microenvironment are essential for PDAC tumorigenesis. To test this hypothesis, we employed a transgenic spontaneous PDAC mouse model and observed an early influx of mast cells to the tumor microenvironment, which suggests that mast cells in the tumor microenvironment are essential for PDAC tumorigenesis. We investigated the contribution of mast cells to PDAC tumorigenesis by using a mast cell-deficient mouse model (Kitw-sh/w-sh) (18). We further assessed the clinical relevance by correlating mast cell infiltration with the survival of patients with PDAC. Our results indicate that mast cells play a key role in PDAC tumorigenesis and present a novel therapeutic target.

Materials and Methods

Mouse models

K-RasG12V mutation mice were developed by our group (4). The K-RasG12V knockin mice have been described previously (4). Briefly, K-RasG12V was engineered following a human cytomegalovirus and chicken β-actin chimeric promoter (CAG) and blocked by the proximal insertion of a loxp-green fluorescent protein (GFP)-stop-loxp cassette (cLGL-KRasG12V). cLGL-K-RasG12V mice were crossed with Ela-CreERT mice, which targeted the expression of high levels of mutant Kras in pancreatic acinar cells (4). C57BL/6 wild-type (WT) mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. Mast cell-deficient mice on a C57BL/6 background (Kitw-sh/w-sh) were gifts from Dr. Stephen E. Ullrich and from The Jackson Laboratory. The mice were housed in facilities approved by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International. The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all the animal procedures described here (4, 19).

Immunohistochemical and histochemical staining with image analysis

Immunohistochemical studies were performed using markers for inflammatory cells, including leukocytes (CD45), neutrophils (Gr-1), macrophages (F4/80), and mast cells, on 4-μm unstained sections from the human tissue microarray blocks and mouse pancreatic tissue blocks using a mouse monoclonal antibody against CD45 (Biocare Medical). To retrieve the antigenicity, we treated the tissue sections at 100 °C in a steamer containing 10 mM citrate buffer (pH, 6.0) for 1 hour. The sections were then immersed in methanol containing 0.3% hydrogen peroxidase for 20 minutes to block endogenous peroxidase activity and were incubated in 2.5% blocking serum to reduce nonspecific binding. The sections were then incubated for 1 hour at 37°C with anti-CD45 at a 1:50 dilution. Standard avidin-biotin immunohistochemical analysis of the sections was done according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (Vector Laboratories). Vector Red was used as a chromogen, and hematoxylin was used for counterstaining.

Toluidine blue staining (pH, 2.0~2.5) for mast cells was performed on continuous slides next to the slides stained for CD45.

The staining results were evaluated independently by two gastrointestinal pathologists to determine the percentage of positive cells in each core quantitatively using the Ariol automated image analysis system (Applied Imaging Corp.).

RNA extraction from pancreatic tissues in mice, cDNA microarray hybridization, and quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase PCR (q-RT-PCR) in superarray

Pancreatic tissues were selected according to different lesion stages in mice: normal pancreatic (NP) tissue from K-ras WT mice; bulk pancreatic tissue from K-rasG12V mice that had been morphologically confirmed as chronic pancreatitis (CP); bulk pancreatic tissue from K-rasG12V mice that had been morphologically confirmed as stage I, II, or III pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) on a CP background; and bulk pancreatic tissue from K-rasG12V mice that had been morphologically confirmed as PDAC in a pool of CP. Total RNA was isolated from mouse tissue samples using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To determine the expression profile of K-rasG12V mice, we performed RNA hybridization on cDNA microarrays using the MouseWG-6 Expression BeadChip Kit v2.0 (Illumina, Inc.). Expression was confirmed by 15 q-RT-PCR analyses performed with a superarray kit (SABiosciences).

Cell culture and adoptive intraperitoneal transfer of bone marrow-derived mast cells into Kitw-sh/w-sh mice for mast cell reconstitution and Panc-02 PDAC cell implantation

Panc-02 PDAC cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 containing 10% fetal bovine serum. Bone marrow stem cells were isolated from the femurs and tibiae of 6-week-old C57BL/6 mice and then cultured at a concentration of 106 cells/ml in complete RPMI 1640 supplemented with murine rIL-3 (10 ng/ml; PeproTech) and stem cell factor (10 ng/ml; PeproTech). Nonadherent cells were transferred to fresh culture media twice per week for 4–5 weeks, at which point >98% of viable cells were mast cells, as verified by flow cytometry (CD45+CD117+FcεR1+CD3−B220−) and positive staining for toluidine blue (19). A total of 1 × 107 bone marrow-derived mast cells per mouse was injected intraperitoneally into mast cell-deficient mice. Six weeks later, 2.5 × 105 Panc-02 PDAC cells were orthotopically implanted into the pancreas of each Kit−/− mouse and WT C57BL/6 mouse. Another 2 weeks later, five mice from each group were euthanized every 7 days, and tumor sizes and weights were measured. An additional 15 mice were used for survival analysis.

Orthotopic PDAC mouse models

To perform the intrapancreatic injection, we anesthetized mice with 2.5% tribromoethanol and made a 0.5–1-cm incision in the left subcostal region. Panc-02 PDAC tumor cells were injected into the caudal pancreas (20). The peritoneum and skin were closed with the EZ Clip wound-closing kit (Stoelting Co.). At 2 weeks after implantation, five mice from each group were euthanized every 7 days, and PDAC tumors were evaluated macroscopically for the presence of orthotopic tumors and metastases in the abdominal cavity (20). Tumor volumes were estimated using the following formula: (π × long axis × short axis × short axis) ÷ 6 (21). An additional 40 mice in each group were used for survival analysis.

Patients and tissue samples

We searched the patient record database at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center for patients with stage II PDAC who had undergone pancreaticoduodenectomy there between 1990 and 2005 and had not received any form of preoperative chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Patients who had received preoperative chemotherapy or radiotherapy or had died from postoperative complications were excluded from our study. Our search identified 67 patients who met those criteria: 45 men and 22 women whose median age at the time of surgery was 63.7 years (range, 39.8–79.9 years). The patients’ follow-up information through August 2008 was extracted from the prospectively maintained institutional pancreatic cancer database managed in the Department of Surgical Oncology and, if necessary, updated by review of the U.S. Social Security Index. Overall survival was calculated as the time from the date of diagnostic biopsy or surgery (if biopsy was not diagnostic) to the date of death or the date of last follow-up if death did not occur. The median follow-up time was 27.5 months. We constructed tissue microarrays using formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded archival tissue samples from our patient population. The Institutional Review Board of MD Anderson Cancer Center approved this study.

Archival tissue blocks and their matching hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides were retrieved, reviewed, and screened by a gastrointestinal pathologist (H. W.) to identify representative tumor regions and non-neoplastic pancreatic parenchyma. For each patient, two cores of tumor tissue and two cores of paired benign pancreatic tissue were sampled from representative areas using a 1.0-mm punch. The tissue microarrays were constructed with a tissue microarrayer (Beecher Instruments, Sun Prairie, WI) as described previously (22). The cutoff point of the mast cell score was 3.68 (i.e., 75th percentile of the mast cell score in the sample population.

Statistical analysis

Student’s t-tests and one-way analysis of variance were used to compare quantification data. Survival probability curves were constructed using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the log-rank test was used to evaluate the statistical significance of differences.

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences software (SPSS Inc.). We used a two-sided significance level of 0.05 for all statistical analyses.

Results

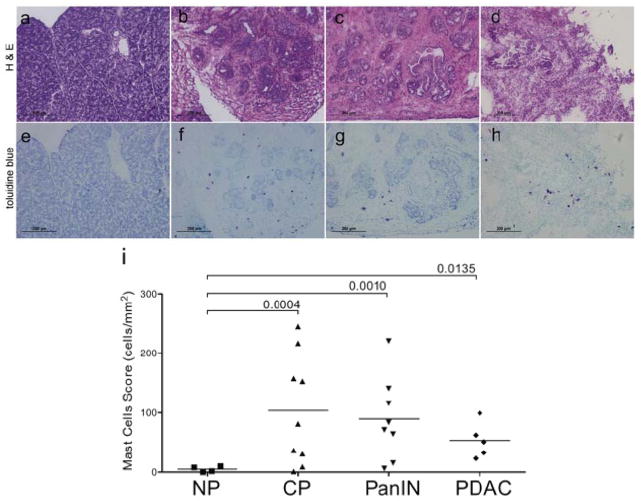

Mast cell early infiltration and mast cell cytokine expression are associated with PDAC development in a transgenic spontaneous mouse model

To measure mast cell influx during the development of PDAC, we utilized a transgenic K-rasG12V mouse model that developed CP, PanINs, and invasive PDAC (4). In our study, CP was defined morphologically by the loss of acinar cells, fibrosis, and infiltration of inflammatory cells, including monocytes and lymphocytes, without evidence of PDAC. Pancreatic tissue was obtained at various stages and grouped by pathologic results: NP (N = 9) CP (N = 9), PanIN (N = 9), and PDAC (N = 4). Pancreatic tissues (N = 4) obtained from WT littermates served as controls. K-rasG12V mice had an early influx of inflammatory cells to the tumor microenvironment. The mast cell staining index scores for NP, CP, PanIN, and PDAC tissues were 5, 104, 83, and 58, respectively (Figure 1). The influx of mast cells in CP persisted through the development of PanIN and PDAC. There was no significant difference in mast cell scores between CP and different stages (i.e., I–III) of PanIN and PDAC. While mast cells were evenly distributed in CP and PanIN lesions, they accumulated at the infiltrating edges of the tumor. Because of this uneven distribution in PDAC, the mast cell score (normalized to the area of the whole pancreas) in some cases seemed lower in PDAC than in CP.

Figure 1.

Mast cell infiltration during PDAC development in K-rasG12V mice. (a and e) Few mast cells were found in NP tissue (200x). (b and f) Influx of mast cells in CP (200x). (c and g) Influx of mast cells in PanIN (200x). (d and h) Influx of mast cells in PDAC (200x). (a-d) Hematoxylin and eosin staining. (e-h) Toluidine blue staining. Serial sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and toluidine blue; mast cells were stained red-purple (metachromatic staining against a blue background). (i) Quantitative evaluation of mast cell infiltration in pancreatic tissues (score = the ratio of the total number of mast cells to the area of pancreas) during PDAC development. The P values for the comparison between CP, PanIN, and PDAC vs. NP are as indicated. The P values for the comparison of PDAC vs. CP and PDAC vs. PanIN were all > 0.5, showing no statistical difference.

Mast cells in the tumor microenvironment are required for PDAC tumor growth in vivo

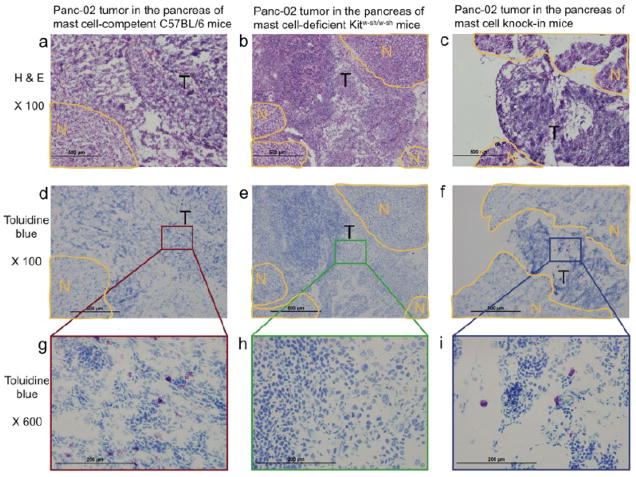

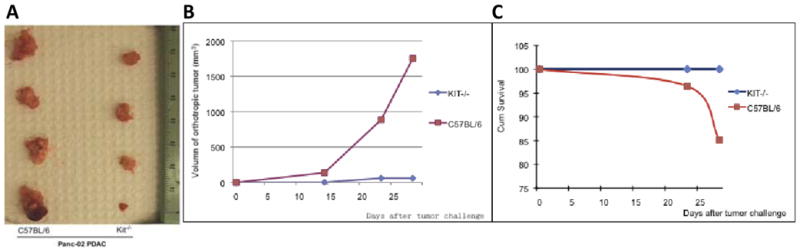

To determine the contribution of mast cells to the tumorigenesis of PDAC, we compared tumor growth in mast cell-deficient Kitw-sh/w-sh mice (Kit−/− mice) and syngeneic C56BL/6 mice (WT mice). When Panc-02 PDAC cells, a tumorigenic murine PDAC cell line derived from a methylcholanthrene-induced tumor growing in a male C57BL/6 mouse, were orthotopically implanted in the pancreas, the growth of tumor was significantly suppressed in mast cell-deficient Kitw-sh/w-sh mice compared to syngeneic C56BL/6 mice; only 20% of Kit−/− mice had measurable tumors 28 days after implantation compared to 100% of WT mice (P = 0.033) (Figure 2). The Kit−/− mice also had a lower incidence of hemorrhagic ascites than did the WT mice (17% vs. 75%). Moreover, the Kit−/− mice lived significantly longer than the WT mice. Mast cells were found in the tumors of WT C57BL/6 mice (Figure 4a, d, g), and as expected, no mast cells were found in the pancreases of Kit−/− mice (Figure 4b, e, h). Similar results were observed in a subcutaneous model with Panc-02 cells (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Suppressed PDAC growth in mast cell-deficient mice. (a) Panc-02 PDAC tumors were larger in WT C57BL/6 mice (left) than in mast cell-deficient Kitw-sh/w-sh mice (right). (b) Tumor growth in WT and Kitw-sh/w-sh mice implanted with Panc-02 cells. Growth in WT mice is shown in red, and growth in mast cell-deficient mice is shown in green. (c) Survival curves of WT mice (red) and Kitw-sh/w-sh mice (green) implanted with Panc-02 cells.

Figure 4.

Mast cells in orthotropic Panc-02 tumors in WT C57BL/6 mice (a, d, g; left panel,), mast cell-deficient mice (b, e, f; middle panel), and mast cell-reconstituted mice (c, f, i; right panel). (a, b, c) Hematoxylin and eosin staining, 100x: N = benign area with NP structure and T = tumor. (d, e, f) Toluidine blue staining, 100x. (g, h, i) Toluidine blue staining, 600x.

To further confirm the hypothesis that mast cells promote PDAC tumorigenesis, we employed a mast cell reconstitution mouse model. Bone marrow-derived mast cells from WT C56BL/6 mice were injected into mast cell-deficient Kit−/− mice and repopulated in the pancreatic tissues. Tumor growth was significantly increased in the Kit−/− mice repopulated with mast cells compared with the parental Kit−/− mice (P = 0.009) (Figure 3). Mast cell reconstitution also increased the incidence of hemorrhagic ascites to 50%. The repopulation of mast cells was confirmed by both hematoxylin and eosin and toluidine blue staining (Figure 4c, f, i). These data support the critical role of mast cells in PDAC progression.

Figure 3.

Reconstitution of mast cells restores PDAC growth in mast cell-deficient mice. Panc-02 PDAC tumor size in WT (red), Kitw-sh/w-sh (green), and mast cell-reconstituted Kitw-sh/w-sh mice (blue) was measured 28 days after Panc-02 implantation. P values were determined using one-way analysis of variance

Mast cells infiltration predicts a worse prognosis of patients with PDAC

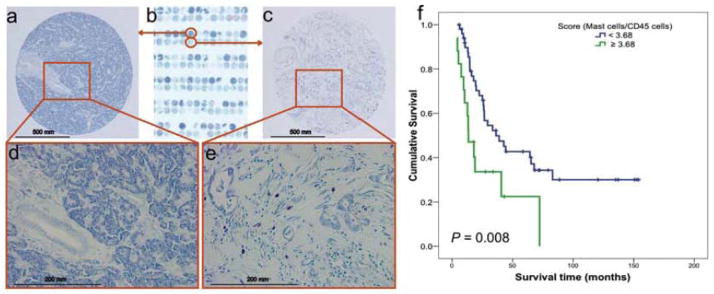

To determine the clinical relevance of mast cell influx in PDAC, we stained 67 pancreaticoduodenectomy specimens from a previously constructed tissue microarray with toluidine blue and counted the mast cells (Figure 5a–e). Patients with mast cell scores < 3.68 survived significantly longer (median overall survival duration, 36.2 ± 9.4 months) than did patients with mast cell scores ≥ 3.68 (median overall survival duration, 13.4 ± 3.4 months; P = 0.008, high vs. low mast cell infiltration) (Figure 5f). In addition, the incidence of recurrence was lower in patients with mast cell scores < 3.68 (67%) than in patients with mast cell scores ≥ 3.68 (100%; P = 0.003, Fisher’s exact test.). In multivariate analysis (Supplemental Table), master cell score is close to, but does not reach statistical significance (hazard ratio: 1.88, 95% confidence interval: 0.95–3.73, p=0.07) after adjusting lymph node status. The lymph node metastasis is an independent prognostic factors for poor survival (hazard ratio: 2.31, 95% confidence interval: 1.10–4.84 p=0.03).

Figure 5.

Association of mast cell infiltration with survival of patients with PDAC. No mast cells were found in NP tissues. (a) 100x and (d) 400x. (b) A human PDAC tissue microarray was stained with toluidine blue. Mast cells were found in the human PDAC tumor microenvironment: (c) 100x and (e) 400x. Mast cells stained red-purple (metachromatic staining), and the background was blue (orthochromatic staining). (f) The mast cell score was correlated with survival in patients with PDAC. The mast cell score was normalized as the ratio of the number of mast cells to the percentage of pan-leukocytes (CD45-positive cells). The cutoff point of the mast cell score was set at 3.68. Upper curve, patients with mast cell scores < 3.68; lower curve, patients with mast cell scores ≥ 3.68. The P value was derived using the log-rank statistic.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that mast cells play a role in the development and progression of PDAC, a deadly disease with limited treatment options. We found (1) an early influx of mast cells in K-ras mutation-driven spontaneous PDAC, which mimics human PDAC, (2) the necessity of mast cells in vivo for PDAC tumor growth, and (3) the clinical relevance of mast cells in PDAC. These findings indicate that mast cells are essential for PDAC progression and present a potential therapeutic target.

Mast cells are important in allergic and late-phase reactions, inflammation, and the regulation of adaptive T-cell-mediated immunity (23–25). However, the role of mast cells in the tumorigenesis of cancers is not totally clearly, and data regarding their benefit or detriment to tumorigenesis have been controversial, depending on the local stromal conditions (26). On the one hand, mast cells may promote tumor development by (1) facilitating tumor angiogenesis through heparin-like molecules, and heparin could further permit neovascularization and metastasis through its anti-clotting effects (27); (2) secreting histamine and growth factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor, stem cell factor, and nerve growth factor, which may facilitate the proliferation of tumor cells, and (3) contributing proteolytic components necessary for tumor invasiveness (28). On the other hand, mast cells could also be detrimental to tumor growth by secreting several cytokines, such as IL-4, and proteolytic enzymes that may induce the apoptosis of malignant cells (29). Consistent with the dual roles of mast cells in inhibiting or promoting tumor growth, high mast cell numbers represent a good prognostic indicator in breast cancer, non-small cell lung carcinoma, and ovarian cancer (16, 17), but they are associated with poor prognosis in skin cancer (both melanoma and non-melanoma and Merkel cell tumors) (13, 14), oral squamous cell carcinoma, several types of lymphoma, and prostate cancer (16, 17).

Inflammation is associated with an increased risk for most cancers. CP produces pancreatic inflammation and is associated with an increased risk of PDAC, thus establishing a link between cancer and inflammation on an epidemiological level (2, 3). To determine the role of mast cells in PDAC tumorigenesis, we first determined when and how much mast cells infiltrate the PDAC tumor microenvironment, using a K-rasG12V transgenic spontaneous mouse model (4). Activating K-RAS point mutations at codon 12 (from GGT to GAT or GTT, and more rarely, CGT) results in the substitution of glycine with aspartate, valine, or arginine. These mutations are the first known genetic alterations in PDAC, occurring sporadically in normal pancreatic tissue, and are detected in 30% of early neoplasms, with the frequency rising to nearly 100% in advanced PDAC (32, 33). PDACs nearly always arise from precursors that sustain activating K-RAS mutations, whereas such mutations are almost never seen in less common pancreatic cancers such as islet cell carcinomas (34, 35). Thus, the PDAC generated in this mouse model mimicked the tumorigenesis of human PDAC. Our results showed that mast cell infiltration was an early event and that mouse mast cells distributed into CP and mouse PanIN lesions but were rarely found in NP tissues. During the development of PDAC, mast cells accumulate to the tumor microenvironment. Using qRT-PCR analysis, we noted that during the progression from NP to CP to PanIN to PDAC, many cytokines, particularly mast cell-related cytokines and receptors (e.g., CXCL5, IL-8rb, IL1β, and tumor necrosis factor) were consistently upregulated in the microenvironment during PDAC development in K-rasG12V mice (data not shown). These results suggest that mast cells migrate into the tumor microenvironment and play a critical role in PDAC development.

To assess the causative role of mast cells in PDAC tumorigenesis, we manipulated mast cells in vivo to document the necessity of mast cells for PDAC tumor growth. In Kitw-sh/w-sh mast cell-depleted mice, the growth of transplanted (both orthotopically and subcutaneously) tumors and incidence of hemorrhagic ascites were much lower than in WT C57BL/6 mice, and the survival of tumor-bearing Kitw-sh/w-sh mice was prolonged compared to tumor-bearing WT mice. These data indicate that mast cells are an important part of the tumor microenvironment for PDAC growth. When reconstituted Kitw-sh/w-sh mice intraperitoneally with bone marrow-derived cultured mast cells (BMCMCs) from WT (Kit+/+) mice (WT BMCMC → Kitw-sh/w-sh mice) (18, 36), the growth of mouse PDAC tumor and changes in the tumor microenvironment in this reconstitution model recapitulated those found in WT mice, further supporting the hypothesis that mast cells support PDAC tumor growth and progression.

Furthermore, the observed role of mast cells in PDAC tumorigenesis in mouse models is also clinically relevant. Our results showed that high mast cell infiltration into the tumor microenvironment was predictive of poor clinical outcomes in patients with PDAC.

The exact mechanism by which mast cells contribute to PDAC development is not entirely clear and is beyond the scope of the current study. However, two recent studies and the data reported in this paper yield valuable insights. Soucek et al. showed in a -cell tumor model that activation of Myc in vivo triggered rapid recruitment of mast cells to the tumor site, a recruitment that is absolutely required for macroscopic tumor expansion, and that treatment of established -cell tumors with a mast cell inhibitor rapidly triggered hypoxia and cell death of tumor and endothelial cells (30). They observed that mast cell-induced angiogenesis was the key mechanism that promoted the growth of pancreatic islet cell tumors. These data suggest that inhibition of mast cell function may prove therapeutically useful in restraining the expansion and survival of pancreatic and other cancers. In human PDAC, Strouch et al. (31) found that increased mast cell infiltration into the tumor site was correlated with poor patient survival. In addition, they demonstrated that the mast cell-conditioned medium promoted tumor growth in vitro. Our findings confirm the observation that increased mast cell infiltration is associated with poor prognosis. Other studies in our group are under way to address the mechanism by which mast cells contribute to PDAC development.

In summary, we identified a previously undescribed role of mast cells in PDAC. Mast cells migrate to the tumor site and provide a tumor microenvironment that allows for tumor progression. These results highlight the practical importance of mast cells in PDAC and indicate that targeting mast cells may be a promising novel therapy for PDAC.

Supplementary Material

STATEMENT OF TRANSLATIONAL RELEVANCE.

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is one of the leading causes of cancer death, and no effective therapy is currently available for it. We have identified a previously undescribed role of mast cells in PDAC. Mast cells migrate to the tumor site and provide a microenvironment that allows for tumor progression. These results highlight the practical importance of mast cells in PDAC and indicate that targeting mast cells may be a promising novel therapy for PDAC.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Willem Overwijk for critical suggestions, Dr. Hui Zhao for statistical assistance, Dr. Woonyoung Choi for help with the microarray analysis, and Dr. Stephen E. Ullrich for providing initial Kitw-sh/w-sh mice and helpful comments.

Financial support: This work was supported by an American Society of Clinical Oncology Young Investigator Award (DZC), NIH grant CA128927 (DZC), AACR-PanCAN Career Development Award (HW), DK052067 and DK068414 (CDL), and MD Anderson Pancreatic SPORE grant P20 CA101936 (JLA). This research was also supported in part by the NIH through MD Anderson’s Cancer Center Support grant (CA16672).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions

DZC, PH, and CL designed the experiments. YM, BJ, YL, and DD performed experiments. HW provided pathology support. JLA and YL provided scientific advice and helpful comments; DZC and YM wrote the initial draft of the manuscript; and all the authors provided input on the final version. DZC supervised the project.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farrow B, Evers BM. Inflammation and the development of pancreatic cancer. Surgical Oncology. 2002;10:153–69. doi: 10.1016/s0960-7404(02)00015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P, Cavallini G, Ammann RW, Lankisch PG, Andersen JR, Dimagno EP, Andren-Sandberg A, Domellof L. Pancreatitis and the risk of pancreatic cancer. International Pancreatitis Study Group. New England Journal of Medicine. 1993;328:1433–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305203282001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ji B, Tsou L, Wang H, Gaiser S, Chang DZ, Daniluk J, Bi Y, Grote T, Longnecker DS, Logsdon CD. Ras Activity Levels Control the Development of Pancreatic Diseases. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1072–82.e1076. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.05.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liotta L, Kohn A. The microenvironment of the tumour-host interface. Nature. 2001;411:375–79. doi: 10.1038/35077241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fidler IJ. The organ microenvironment and cancer metastasis. Differentiation. 2002;70:498–505. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2002.700904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tlsty TD, Coussens LM. Tumor stroma and regulation of cancer development. Annu Rev Pathol. 2006;1:119–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.1.110304.100224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zigrino P, Loffek S, Mauch C. Tumor-stroma interactions: their role in the control of tumor cell invasion. Biochimie. 2005;87:321–28. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2004.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark CE, Beatty GL, Vonderheide RH. Immunosurveillance of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: insights from genetically engineered mouse models of cancer. Cancer Letter. 2009;279:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galli SJ, Kalesnikoff J, Grimbaldeston MA, Piliponsky AM, Williams CM, Tsai M. Mast cells as “tunable” effector and immunoregulatory cells: recent advances. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:749–86. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galli SJ, Nakae S, Tsai M. Mast cells in the development of adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:135–42. doi: 10.1038/ni1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalesnikoff J, Galli SJ. New developments in mast cell biology. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1215–23. doi: 10.1038/ni.f.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grimbaldeston MA, Pearce AL, Robertson BO, Coventry BJ, Marshman G, Finlay-Jones JJ, Hart PH. Association between melanoma and dermal mast cell prevalence in sun-unexposed skin. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:895–903. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grimbaldeston MA, Skov L, Baadsgaard O, Skov BG, Marshman G, Finlay-Jones JJ, Hart PH. High dermal mast cell prevalence is a predisposing factor for basal cell carcinoma in humans. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:317–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beer TW, Ng LB, Murray K. Mast cells have prognostic value in Merkel cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:27–30. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e31815c932a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ribatti D, Crivellato E. The controversial role of mast cells in tumor growth. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2009;275:89–131. doi: 10.1016/S1937-6448(09)75004-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galinsky DS, Nechushtan H. Mast cells and cancer-No longer just basic science. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2008;68:115–30. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grimbaldeston MA, Chen C, Piliponsky AM, Tsai M, Tam SY, Galli SJ. Mast cell-deficient W-sash c-kit mutant KitW-sh/W-sh mice as a model for investigating mast cell biology in vivo. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:835–48. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62055-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Byrne SN, Limon-Flores AY, Ullrich SE. Mast cell migration from the skin to the draining lymph nodes upon ultraviolet irradiation represents a key step in the induction of immune suppression. J Immunol. 2008;180:4648–55. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li M, Bharadwaj U, Zhang R, Zhang S, Mu H, Fisher WE, Brunicardi FC, Chen C, Yao Q. Mesothelin is a malignant factor and therapeutic vaccine target for pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:286–96. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suzuki E, Kapoor V, Jassar AS, Kaiser LR, Albelda SM. Gemcitabine selectively eliminates splenic Gr-1+/CD11b+ myeloid suppressor cells in tumor-bearing animals and enhances antitumor immune activity. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:6713–21. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eytan E, et al. Two different mitotic checkpoint inhibitors of the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome antagonize the action of the activator CDC20. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:9181–85. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804069105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mekori YA, Metcalfe DD. Mast cells in innate immunity. Immunol Rev. 2000;173:131–40. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2000.917305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Redegeld FA, Nijkamp FP. Immunoglobulin free light chains and mast cells: pivotal role in T-cell-mediated immune reactions? Trends Immunol. 2003;24:181–85. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pedotti R, De Voss JJ, Steinman L, Galli SJ. Involvement of both ‘allergic’ and ‘autoimmune’ mechanisms in EAE, MS and other autoimmune diseases. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:479–84. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00233-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Theoharides TC, Conti P. Mast cells: The JEKYLL and HYDE of tumor growth. Trends in Immunology. 2004;25:235–41. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Samoszuk M, Kanakubo KE, Chan JK. Degranulating mast cells in fibrotic regions of human tumors and evidence that mast cell heparin interferes with the growth of tumor cells through a mechanism involving fibroblasts. BMC Cancer. 2005;21:121. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-5-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Almholt K, Johnsen M. Stromal cell involvement in cancer. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2003;162:31–42. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-59349-9_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gooch JL, Lee AV, Yee D. Interleukin 4 inhibits growth and induces apoptosis in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1998;15:4199–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soucek L, Lawlor ER, Soto D, Shchors K, Swigart LB, Evan GI. Mast cells are required for angiogenesis and macroscopic expansion of Myc-induced pancreatic islet tumors. Nat Med. 2007;13:1211–18. doi: 10.1038/nm1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strouch MJ, Cheon EC, Salabat MR, Krantz SB, Gounaris E, Melstrom LG, Dangi-Garimella S, Wang E, Munshi HG, Khazaie K, Bentrem DJ. Crosstalk between mast cells and pancreatic cancer cells contributes to pancreatic tumor progression. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;16:2257–65. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klimstra DS, Longnecker DS. K-ras mutations in pancreatic ductal proliferative lesions. Am J Pathol. 1994;145:1547–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rozenblum E, et al. Tumor-suppressive pathways in pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1731–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murtaugh L, Leach C. A case of mistaken identity? Nonductal origins of pancreatic “ductal” cancers. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:211–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guerra C. Chronic pancreatitis is essential for induction of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma by K-Ras oncogenes in adult mice. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:291–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grimbaldeston MS, Nakae S, Kalesnikoff J, Tsai M, Galli SJ. Mast cell-derived interleukin 10 limits skin pathology in contact dermatitis and chronic irradiation with ultraviolet B. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1095–104. doi: 10.1038/ni1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.