Abstract

Context

Multiphoton microscopy (MPM) based on 2-photon excitation fluorescence and second-harmonic generation allows simultaneous visualization of cellular details and extracellular matrix components of fresh, unfixed, and unstained tissue. Portable multiphoton microscopes, which could be placed in endoscopy suites, and multiphoton endomicroscopes are in development, but their clinical utility is unknown.

Objectives

To examine fresh, unfixed endoscopic biopsies obtained from the distal esophagus and gastroesophageal junction to (1) define the MPM characteristics of normal esophageal squamous mucosa and gastric columnar mucosa, and (2) evaluate whether diagnosis of intestinal metaplasia/Barrett esophagus (BE) could be made reliably with MPM.

Design

The study examined 35 untreated, fresh biopsy specimens from 25 patients who underwent routine upper endoscopy. A Zeiss LSM 710 Duo microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, New York) coupled to a Spectra-Physics (Mountain View, California) Tsunami Ti:sapphire laser was used to obtain a MPM image within 4 hours of fresh specimen collection. After obtaining MPM images, the biopsy specimens were placed in 10% buffered formalin and submitted for routine histopathologic examination. Then, the MPM images were compared with the findings in the hematoxylin-eosin–stained, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections. The MPM characteristics of the squamous, gastric-type columnar and intestinal-type columnar epithelium were analyzed. In biopsies with discrepancy between MPM imaging and hematoxylin-eosin–stained sections, the entire tissue block was serially sectioned and reevaluated. A diagnosis of BE was made when endoscopic and histologic criteria were satisfied.

Results

Based on effective 2-photon excitation fluorescence of cellular reduced pyridine nucleotides and flavin adenine dinucleotide and lack of 2-photon excitation fluorescence of mucin and cellular nuclei, MPM could readily identify and distinguish among squamous epithelial cells, goblet cells, gastric foveolar-type mucous cells, and parietal cells in the area of gastroesophageal junction. Based on the cell types identified, the mucosa was defined as squamous, columnar gastric type (cardia/fundic-type), and metaplastic columnar intestinal-type/BE. Various types of mucosa seen in the study of 35 biopsies included normal squamous mucosa only (n = 14; 40%), gastric cardia-type mucosa only (n = 2; 6%), gastric fundic mucosa (n = 6; 17%), and both squamous and gastric mucosa (n = 13; 37%). Intestinal metaplasia was identified by the presence of goblet cells in 10 of 25 cases (40%) leading to a diagnosis of BE on MPM imaging and only in 7 cases (28%) by histopathology. In 3 of 35 biopsies (9%), clear-cut goblet cells were seen by MPM imaging but not by histopathology, even after the entire tissue block was sectioned. Based on effective 2-photon excitation fluorescence of elastin and second-harmonic generation of collagen, connective tissue in the lamina propria and the basement membrane was also visualized with MPM.

Conclusions

Multiphoton microscopy has the ability to accurately distinguish squamous epithelium and different cellular elements of the columnar mucosa obtained from biopsies around the gastroesophageal junction, including goblet cells that are important for the diagnosis of BE. Thus, use of MPM in the endoscopy suite might provide immediate microscopic images during endoscopy, improving screening and surveillance of patients with BE.

Barrett esophagus (BE) is the condition in which metaplastic columnar epithelium replaces the normal stratified squamous epithelium that usually lines the distal esophagus.1,2 Barrett esophagus predisposes a patient to esophageal adenocarcinoma, a tumor with increasing incidence and high mortality; thus, the early diagnosis of BE is important.3–6 Patients with BE have a 30-fold to 125-fold increased risk for esophageal adenocarcinoma compared with the general population.7 A proposed strategy for diagnosing BE in clinic is to use endoscopy to screen patients with chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease.8,9 Meta-analyses estimate that the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma among individuals with BE is 7 per 1000 (range, 6–9) person-years’ duration of follow-up, with no detectable geographic variation.10 The overall 5-year survival rates of adenocarcinoma in the distal esophagus are 14% for stage III and 0% for stage IV disease but are 81% for stage I and 51% for stage II.5 At the same time, patients with BE have an increased risk of mortality, and much of that excess risk is from causes of death other than esophageal adenocarcinoma, such as bronchopneumonia and ischemic heart disease.11

The spatial resolution of available, modern endoscopic techniques, such as white-light endoscopy, magnification endoscopy, chromoendoscopy, narrow-band imaging, and trimodal imaging, cannot reach cellular and subcellular levels, although some of these techniques permit or improve visualization of both vascular and glandular patterns.12,13 Confocal laser endomicroscopy is a newly developed tool that allows in vivo, microscopic, histologic analysis of the mucosal layer in real-time during endoscopy.14–16 Barrett esophagus, as well as Barrett-associated neoplastic changes, can be diagnosed with high accuracy with confocal laser microscopy.17–20 However, this technique requires exogenous fluorescent contrast agents to increase imaging contrast because the natural fluorescence of the gastrointestinal mucosa is not intense enough to allow detailed microscopic imaging. Moreover, confocal imaging of gastrointestinal mucosa using fluorescein does not specifically label the cell nucleus or other features that are important for identification of dysplasia. The contrast agent also brings an additional, albeit small, risk to the endoscopic procedure.21 An additional minor concern is that patients who receive fluorescein will have yellow skin, eyes, and urine for several hours after the procedure. These considerations are limitations to its clinic application.15,22 Optical coherence tomography is another technique that has been used to create 3-dimesional images of tissues and could be potentially combined with confocal microscopy for a variety of clinical applications.23–25 These techniques have been applied to detect intestinal metaplasia in BE, and dysplastic changes and inflammation in intestinal tissues.26–28

Multiphoton microscopy (MPM), using a near-infrared, femtosecond-pulsed laser as a light source, has the potential to overcome the limitations of confocal fluorescence microscopy while retaining its merits.29,30 The observation of unfixed, unstained samples based on 2 photon excitation fluorescence (TPEF) and second-harmonic generation (SHG) is an emerging application.25 Combined TPEF and SHG imaging allows simultaneous visualization of cellular species and extracellular matrix components without the need for exogenous contrast agents. Particularly effective, TPEF imaging of cellular reduced pyridine nucleotides and flavin adenine dinucleotide makes the nonfluorescent nuclei in a MPM image easily discernable.31 The resolution with the technique approaches 400 nm in the lateral direction and 1000 nm in the axial direction.23 Although MPM has been widely applied to diagnose pathologic tissues, such as skin aging, liver fibrosis, basal cell carcinoma, cervical cancer, gastric cancer, squamous carcinoma, and colonic adenoma,32–37 diagnosis of BE with this technique has not been addressed. In this study, our goals were to (1) define the MPM characteristics of normal esophageal squamous mucosa and gastric columnar mucosa, and (2) evaluate whether diagnosis of intestinal metaplasia/BE could be made reliably with MPM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Twenty-five patients who underwent routine upper endoscopy between October 2010 and May 2011 were recruited to participate in this study at Yale-New Haven Hospital (New Haven, Connecticut). Written, informed consent was obtained from all study participants, and the study was reviewed and approved by the Yale University Human Investigations Committee. Standard biopsy forceps were used to obtain mucosal pinch-biopsy specimens from areas of esophagus, gastroesophageal junction (GEJ), and gastric cardia. The tissue was stored in ice-cold normal saline between the time it was procured and the time it was imaged. All biopsy specimens were placed in glass bottom culture dishes (MatTek, Ashland, Massachusetts) with coverglass (0.085–0.13 mm) for MPM imaging, without any mounting medium because fluids, such as lubricants that have a refractive index that differs significantly from that of water, can potentially reduce spatial resolution. Multiphoton microscopy images were collected within 4 hours of specimen collection to avoid structural degradation of the specimen. No dyes, labels, or probes of any types were used. After obtaining MPM images, the biopsy specimens were placed in 10% buffered formalin and submitted for routine histopathologic examination. Based on morphologic features, diagnoses were made independently based on MPM imaging and histopathologic slides stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E), and then, they were compared. In cases of discrepancies, multiple serial sections were obtained at 4-μm intervals, and entire tissues blocks were exhausted. During endoscopy, the following biopsy specimens were obtained: 10 from normal esophagus in 6 of 25 patients (24%), 10 from areas of reflux esophagitis in 6 of 25 patients (24%), 13 from areas suspicious for BE in 6 of 25 patients (24%), and 11 from normal gastric mucosa in 7 of 25 patients (28%). The histologic and MPM samples were analyzed and classified blindly and separately without knowledge of the endoscopic findings. The diagnosis of BE was made when columnar-appearing mucosa by endoscopic exam was identified extending more than 2 cm above the GEJ and the presence of intestinal metaplasia (goblet cells) was demonstrated on histologic or MPM exam of biopsies from that region.

Multiphoton Microscopy

The multiphoton microscopic images were acquired using a Zeiss LSM 710 Duo microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, New York) coupled to a Spectra-Physics Tsunami Ti:Sapphire laser with a Millennia X Argon pump laser (Spectra-Physics, Mountain View, California) for multiphoton excitation. The intrinsic fluorescent components of cells in specimens were excited at 735 nm, and collagen and elastin were excited at 800 nm.31 For high-resolution imaging, a high-numeric aperture, water immersion objective (C-Apochromat ×40, 1.20-NA) was employed in all experiments for focusing the excitation beam into tissue samples and was also used to collect the backscattered intrinsic TPEF/SHG signals. Each channel in the internal detector covers a spectral width of 369 nm, ranging from 371 to 740 nm, and the selection of detecting wavelength range depends on the collected TPEF/SHG signals. The data files were recorded as serial optical sections, each consisting of 512 × 512 pixels, pseudocolored and overlayed to distinguish between the separate emission channels, and saved in tagged image file format (TIFF) files. The images were viewed on a monitor with a resolution of ~0.25μ/pixel. In our experiments, TPEF and SHG signals were collected between 420 and 680 nm (pseudocolored green) and between 390 and 410 nm (pseudocolored blue), respectively. The images were obtained at a rate of 2.55μs/pixel, and all images had a 16-bit pixel depth. Pseudocoloring and overlaying of the emission channels were performed with Adobe Photoshop (Version 7.0, Adobe, San Jose, California); however, no other manipulation of the images was involved.

RESULTS

Specimen Types

Overall, squamous epithelium was identified in 27 of 35 biopsies (77%), gastric type columnar epithelium (cardia/fundic type) was identified in 21 of 35 biopsies (60%), and metaplastic columnar epithelium with goblet cells was identified in 7 of 35 biopsies (20%) (Table 1). Of the 35 total biopsies, 14 (40%) showed only squamous epithelium, 13 (37%) showed both squamous and gastric columnar junctional mucosa, and 8 (23%) showed gastric type columnar epithelium only. Cells compatible with polymorphonuclear leukocytes (neutrophils or eosinophils) were identified in 3 of 35 biopsies (9%) on MPM imaging in the squamous mucosa, compatible with a diagnosis of reflux esophagitis. These findings were correlated with histopathologic sections, of which 5 of 35 specimens (14%) showed evidence of reflux esophagitis. Intestinal metaplasia was not identified in any of those cases. In biopsies from columnar mucosa at least 2 cm above the GEJ with clinically suspected BE, goblet cells were identified in a total of 10 of 35 cases (29%) on MPM imaging and in only 7 cases (20%) by standard histopathology (Tables 1 and 2). Despite completely exhausting the entire tissue blocks in 3 cases of discrepant results, no goblet cells were identified on paraffin-embedded sections. The characteristics of each epithelium and cell type are described below.

Table 1.

Correlation of Multiphoton Microscopy and Histopathologic Findings in Biopsies From Different Sites

| Location of Biopsy | Histologic Findings, No. (%) | Multiphoton Microscopy Findings | Correlation, No. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Distal esophagus, n = 14 | Squamous mucosa without significant abnormalities, 9 (64) Reflux esophagitis with eosinophils, 5 (36) |

Normal squamous epithelium, 9 (64) Squamous mucosa with possible inflammatory cells, 3 (21) Squamous mucosa with prominent papilla and no inflammatory cells, 2 (14) |

12 (86) |

| Gastroesophageal junction, n = 13 | Squamocolumnar junction with mild chronic inflammation, 6 (46) Focal intestinal metaplasia present, 4 (31) Marked intestinal metaplasia present, 3 (23) |

Gastric columnar cells; no goblet cells present, 2 (15) Squamous epithelium only, 1 (8) Scattered goblet cells identified, 7 (54) Numerous goblet cells identified, 3 (23) |

10 (77) |

| Gastric cardia, n = 2 | Chronic inflammation with reactive changes, 2 (100) | Gastric columnar cells; no goblet cells present, 2 (100) | 2 (100) |

| Gastric fundus, n = 6 | Gastric mucosa without significant abnormalities, 4 (67) Gastric mucosa with mild chronic inflammation, 2 (33) |

Gastric columnar cells identified, 6 (100) | 6 (100) |

Table 2.

Comparison of Multiphoton Microscopy and Histopathology in the Detection of Intestinal Metaplasia

| Cases of BE Determined by MPM, No. (%) | Cases of BE Determined by HPE, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Positive for IM | 10 (100) | 7 (70) |

| Negative for IM | 0 (0) | 3 (30) |

| Total BE | 10 | 10 |

Abbreviations: BE, Barrett esophagus; HPE, histopathologic examination; IM, intestinal metaplasia; MPM, multiphoton microscopy.

MPM Images of Normal Esophageal Epithelium and Reflux Esophagitis

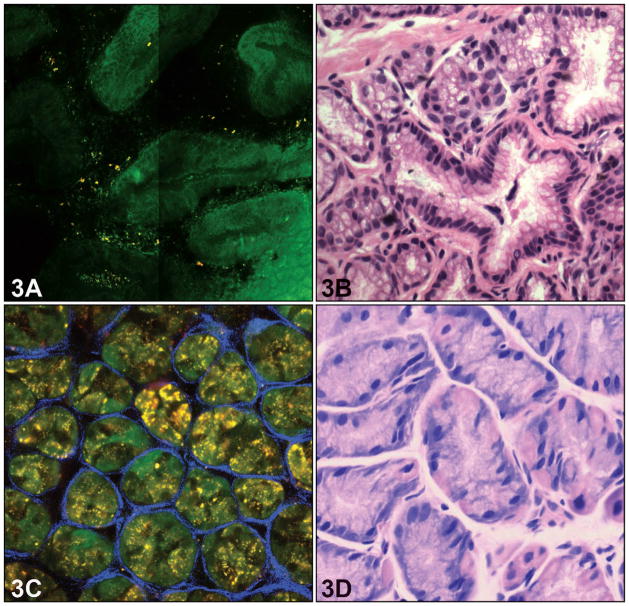

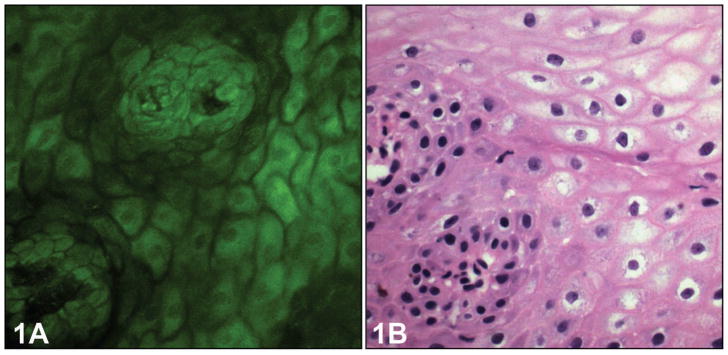

In serial, cross-sectional MPM images, normal esophageal mucosa revealed several characteristics of stratified squamous epithelium of the nonkeratinizing type. Individual squamous cells and the intercellular spaces between individual cells, as well as centrally located nuclei with regular borders, could be readily identified (Figure 1, A). The basal cells were identified in the bottom layers of the squamous epithelium as smaller cells with larger nuclei. The connective tissue papillae (rete pegs), which are formed by invaginations of the lamina propria into the squamous epithelium, were clearly visible in the MPM images. These details correlate with the corresponding H&E light-microscopic images (Figure 1, B). In the epithelium with features of reflux esophagitis, the height of connective tissue papillae was increased, and they appeared to be more prominent because of edema and vascular congestion (Figure 2, A). Occasional polymorphonuclear inflammatory cells could be seen infiltrating into the squamous epithelium as brightly fluorescent cells, although neutrophils could not be distinguished from eosinophils. The corresponding H&E image shows the presence of inflammatory cells in the biopsy (Figure 2, B). Intraepithelial lymphocytes that are normally present in the squamous epithelial cells were not visualized in the MPM images. The collagen fibers from the lamina propria were detected by SHG imaging of collagen, accurately indicating the central position of the papillae. Squamous epithelium was identified in 27 of 35 biopsy specimens (77%) by MPM imaging and showed perfect correlation with routine histology. Features of reflux esophagitis were seen in 5 of 35 biopsy specimens (14%) on routine histology and on only 3 biopsy specimens (9%) with MPM imaging. All polymorphonuclear leukocytes were apparently not equally fluorescent on MPM imaging, leading to that discrepancy.

Figure 1.

Normal esophageal squamous epithelium. A, Multiphoton microscopy image shows architecture of typical squamous epithelium with a single papilla in normal esophagus. B, The corresponding light-microscopic image shows the same feature (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification, ×400).

Figure 2.

Reflux esophagitis. A, Multiphoton microscopy image shows obviously more papillae; however, intraepithelial inflammatory cells are difficult to identify. B, The corresponding light-microscopic image shows the squamous epithelium with intraepithelial neutrophils and lymphocytes (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×400).

MPM Images of Normal Gastric Cardia and Fundic Mucosa

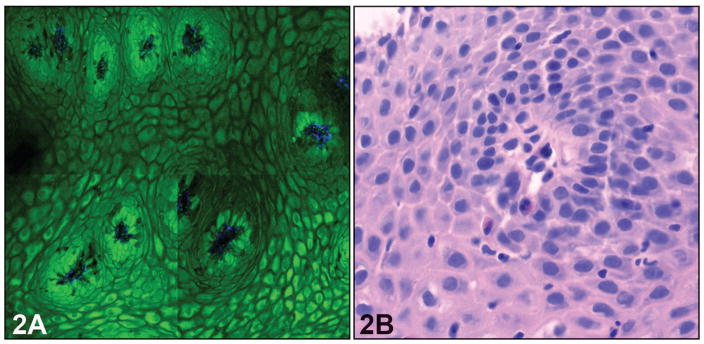

In contrast to the squamous epithelium of the esophagus, the gastric cardia exhibits architecture typical of columnar epithelium. At the upper part of the mucosal layer (≤60 μm), MPM images of cardiac mucosa displayed columnar foveolar gastric mucous neck cells with approximately uniform size and shape (Figure 3, A and B). The round luminal openings with regular basal borders were clearly visible. The mucin of mucosal cells exhibited no TPEF fluorescence and, therefore, showed a dark pattern in MPM images. The nuclei of mucous cells surrounded the glandular opening and so were arranged along the basal surface of the cells. Therefore, these cells could be characterized by their shape, the density of the mucin, and the location of the nucleus, which was barely visible at the bottom of the cell. The other elements of the fundic glands, parietal and chief cells, were present in variable numbers in the cardia-type mucosa. These cells were more numerous in the fundic mucosa, where the glands were more tubular and had shorter foveolae. The parietal cells were brighter with central nuclei and appeared distinct from the chief cells. The corresponding H&E light-microscopic images showed the morphology of the chief and parietal cells in each gastric gland (Figure 3, C and D). Gastric cardia and fundic-type mucosa were identified in 21 of 35 biopsies (60%) and showed perfect correlation between MPM images and routine histology.

Figure 3.

Normal gastric epithelium. A, Multiphoton microscopy image shows architecture of typical columnar epithelium in gastric cardia with gastric glands (≤60 m depth). B, The corresponding light-microscopic images confirm the above features. C, Multiphoton microscopy reveals individual gastric oxyntic glands that are separated by a mesh of collagen fibers at the deeper part of the mucosal layer (≥60 m depth) D, The corresponding light-microscopic image shows there are chief cells and parietal cells in each gastric gland (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnifications ×400 [B and D]).

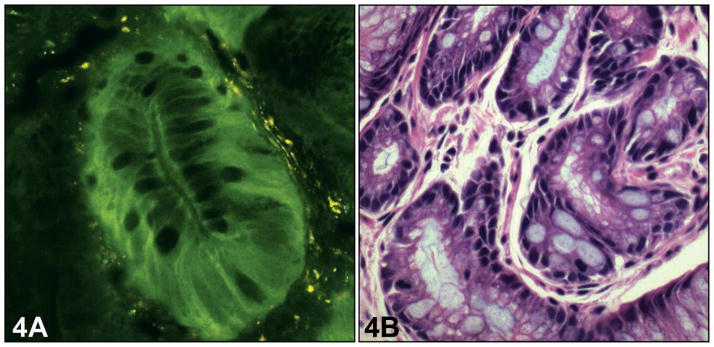

Barrett Esophagus

In this study, diagnosis of BE was made using established criteria; the presence of metaplastic intestinal mucosa with goblet cells 2 cm above the GEJ. Although the information regarding the location of the biopsy was provided by the endoscopist, the identification of the goblet cells was made on morphologic examination of the tissues.38,39 The MPM images revealed the upper part of the mucosa (≤60 μm) as an undulating surface in BE (Figure 4, A). The intestinal-type goblet cells were recognized on MPM images as distinctive, flask-shaped cells containing markedly nonfluorescent mucin, which was even darker than the mucin of the adjacent gastric foveolar cells. These were readily identifiable in the MPM images, even when only a single cell was present in the entire gland or field of view. Although mucin in gastric foveolar mucous neck cells also has less fluorescent signal, it consists of many small round mucin vacuoles, which are less dark than mucin vacuoles of goblet cells. These features help to accurately identify goblet cells in BE. These observations are consistent with the morphology of goblet cells identified on corresponding H&E light-microscopic images (Figure 4, B). The nuclei of gastric foveolar mucous neck cells and goblet cells were uniformly and linearly arranged along the basement membrane and appeared as dark empty spaces. However, the morphology of the nuclei was difficult to evaluate. This is important because it forms the basis of identifying dysplasia in BE. Goblet cells were identified in 10 of 35 biopsies (29%) on MPM images, whereas they were identified on 7 of 35 biopsies (20%) on routine histology (Table 2). The number of cases in this proof-of-principle study was too small to perform any statistical analysis, but MPM imaging seemed roughly comparable in identifying BE relative to routine biopsy, which is considered the gold standard.

Figure 4.

Barrett esophagus without dysplasia at the upper part of the mucosal layer. A, Multiphoton microscopy image shows the specialized columnar epithelium with appearance of goblet cells in Barrett esophagus (≤60 m depth). B, The corresponding light-microscopic image confirms the above features (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×400).

MPM Features of the Connective Tissue Stroma and Inflammatory Cells

There are often changes in the underlying connective tissue stroma in BE. The connective tissue details were appreciated only in a limited number of samples, and the reasons for that discrepancy were unclear. The thickness of the tissues and the metabolic state of the cellular elements may be responsible for the apparent variability among specimens. In some biopsies, a considerable amount of fluorescent material was noted just beneath the surface columnar epithelium, which likely correlated with lipofuscin present in macrophages, which is known to be autofluorescent (Figures 3 and 4). The vascular endothelium, collagen, and elastic fibers and inflammatory cells were not visualized with significant details in most cases. In some biopsies (n = 3; 9%) the collagen bundles in the lamina propria of BE showed the mixture of green and blue color instead of single blue color, coded because of its comparable SHG and TPEF signal yields at the same order of magnitude (Figure 3). The corresponding H&E light-microscopic image showed the same architecture of the collagen fiber (Figure 3, D). The collagen fibers between the glands in the lamina propria could also be visualized. At the deeper part of the mucosa (≥60 μm), the collagen fiber mesh separated individual gastric glands (Figure 3, A). A thin band surrounding individual glands readily indicated the position of the basement membrane. These observations are consistent with the findings on corresponding H&E light-microscopic images (Figure 3, B). The MPM was also capable of revealing the microvasculature of connective tissue stroma in the lamina propria layer, but it could not be seen well enough in most of our samples, which may be related to the thickness of the tissues.

COMMENT

The currently accepted definition of BE is based on the histologic detection of specialized columnar epithelium with goblet cells in the lower esophagus. The diagnosis of the classic long segment of BE requires the presence of intestinal metaplasia more than 2 cm above the GEJ, whereas its presence within 2 cm or at the GEJ only is considered “short-segment” and “ultrashort-segment” BE, respectively. Although the definition of BE has evolved during the years and continues to be controversial, the key element appears to be the presence of metaplastic epithelium in the lower esophagus. Detection of that metaplastic epithelium and its evaluation over time with periodic endoscopic examination and biopsies are the underpinning of surveillance programs for distal esophageal and gastroesophageal adenocarcinomas. However, one of the biggest limitations of these surveillance programs is the inability to localize the metaplastic epithelium on endoscopy because biopsies are often taken randomly according to standard protocols. The chances of sampling errors with this approach are known, and indeed, the incidence of distal esophageal and GEJ cancer continues to rise in Western countries, despite increased surveillance for BE and more endoscopies being performed for various other reasons. This clearly highlights potential limitations of the current endoscopic techniques. There are at least 3 limitations to the current way of making a diagnosis of BE with biopsies: (1) taking biopsies of suspicious-appearing mucosa based on routine white-light endoscopy has sampling-error problems; (2) from the biopsies that are obtained, usually a very limited number of sections (10–15) are cut and, therefore, only a limited portion of the tissue is actually examined by the pathologist, leading to further sampling errors, and even when serial sections are studied, there is considerable tissue wastage and some amount of tissue always remains unexamined; and (3) on histology, the identification of goblet cells can sometimes be problematic. Thus, the need for better methods for identification of cellular details in vivo is obvious for both sampling and diagnostic purposes. The ability to allow the endoscopist to easily identify both the squamocolumnar and GEJ at the level of histologic resolution may result in more reliable identification of metaplastic epithelium, better sampling of mucosa with biopsies, and possibly, earlier diagnosis of neoplasia. Hence, that may improve our ability to reduce the mortality and morbidity associated with distal esophageal and GEJ cancers.

Many endoscopic techniques for examining the esophagus have been developed in recent years, some of which are already in clinical practice or in clinical trials. These include narrow band imaging, optical coherence tomography, and confocal laser endomicroscopy. Although narrow band imaging has some advantages over standard white-light endoscopy in appreciating mucosal details, it does not provide details at the cellular level. Although confocal endomicroscopy provides resolution at the cellular level, MPM has apparent advantages over confocal imaging in visualizing cells within thick tissues and for imaging in vivo.29,30 MPM imaging not only provides visualization of structures within intact tissues at high resolution but also provides subcellular structural details up to a depth of 300 μm to 1 mm, depending on the power of the pump laser. In endoscopic biopsies from the gastrointestinal tract, this allows evaluation of changes throughout the depth of the mucosa, which for various inflammatory, preneoplastic, and early neoplastic disorders is most critical. More recently, multiphoton endoscopy has been exploited for preclinical and clinical applications.40–44 Key challenges for the design considerations focus on the efficient delivery of excitation beam and nonlinear optical signals, the miniaturization of laser-scanning mechanisms, and the flexibility and compactness of a multiphoton probe. Recently, Engelbrecht et al45 devised a novel, ultracompact 2-photon microscope and performed functional calcium imaging in vivo in Purkinje cells of rat cerebellum. Their microscope consisted of a hollow-core photonic crystal fiber for efficient delivery of near-infrared femtosecond laser pulses, a spiral fiber-scanner for resonant beam steering, and a gradient-index lens system for fluorescence excitation, dichroic beam splitting, and signal collection. Based on a double-clad photonic crystal fiber and a 2-dimensional microelectromechanical system scanner, Fu et al46 demonstrated the feasibility of nonlinear optical endoscopy that aims at in vivo 3-dimensional imaging in deep tissue through 3-dimensional, high-resolution imaging from in vitro internal organs and cancer tissues. To increase scanning speed, Tang et al47 introduced an electrostatic microelectromechanical system scanner in their endoscopic MPM system and found that design of a multiphoton probe with a collimation and a focusing lens would provide optimum imaging performance and packaging flexibility. Myaing et al48 used a tubular piezoelectric actuator for achieving 2-dimensional beam scanning and a double-clad fiber for delivery of the excitation light and collection of 2-photon fluorescence to perform real-time imaging of fluorescent beads and cancer cells. These studies provide new impetus toward developing the multiphoton microscopy concept for endoscopic applications.

In this study, we show that imaging with MPM can accurately identify normal squamous esophageal mucosa, normal gastric (cardia/fundic) mucosa, and BE at a resolution comparable to histopathologic examination. Here, we have described the MPM characteristics of squamous and gastric mucosa, reflux esophagitis, and intestinal metaplasia. Based on effective TPEF of cellular nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate and flavin adenine dinucleotide and the lack of TPEF of mucin and cellular nuclei, MPM can easily identify different types of cells, such as squamous epithelial cells, goblet cells, foveolar gastric mucous neck cells, parietal cells, and chief cells. The nonfluorescent mucin in goblet cells displays a very dark pattern with a distinctive, flask-shape in MPM image, which makes it readily identifiable. This can lead to highly targeted sampling of the distal esophagus for not only the diagnosis of BE but also for the histologic evaluation of dysplasia. This was highlighted in 3 of our 35 biopsies (9%), where intestinal metaplasia was identified only with MPM imaging, whereas it was not seen on routine histology, despite serial sectioning of the entire tissue blocks. The number of goblet cells seen on MPM imaging was few and focal in those 3 cases. There is some tissue wastage, even with the most meticulous serial sectioning, and that is a possible explanation for missing the few goblet cells on routine histology in these cases. Thus, our limited observations suggest that MPM imaging can detect even isolated goblet cells, which either required multiple levels on tissue blocks or, in some cases, were completely missed by conventional step sections. Larger and more careful series may help discern the relative diagnostic value of MPM imaging compared with standard histologic examination, which is currently the gold standard. We did not have any cases of dysplasia in our small series, with only 10 of 25 BE cases (40%), but because of the limited nuclear details that were visualized with MPM imaging in this study, this aspect needs further evaluation. However, the boundaries of individual cells and nuclei were clearly revealed in MPM images. It would be straightforward to evaluate the nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio of most of these cells. Because both cytologic and architectural features are important for recognition and grading of dysplasia, MPM imaging has the potential to identify dysplasia and, possibly, early cancer.49 The 3-dimentional reconstruction of mucosal architecture using specialized software could allow improved identification and characterization of dysplastic changes.

Based on effective TPEF of elastin and SHG of collagen, connective tissue in the lamina propria and the position of the basement membrane could be visualized in MPM images. Changes of basement membrane shape and density are usually associated with invasion of malignant cells and changes in the stroma are thought to be important in the development and progression of neoplasia.36–39,49,50 In particular, MPM can provide images as deep as 1 mm by use of a Ti:Al2O3 regenerative amplifier.51 In our study, visualization of stromal tissues was variable among different biopsies. In some biopsies, the stroma was well visualized along with inflammatory cells, whereas in others, the details were less clear. The reasons for this variability are unclear and need further evaluation. However, our findings suggest that MPM imaging has the potential to evaluate stromal changes associated with BE as well as with invasive adenocarcinoma in vivo.

One potential issue that needs to be addressed is the correlation between in vivo appearance of tissue and ex vivo appearance, which can be different. In fact, even the ex vivo appearance of fixed and unfixed specimens can differ. In a prior study,37 MPM imaging of fresh, unfixed gastric mucosal biopsies revealed that gastric glands were not actually packed together as closely as they appear in formalin-fixed, H&E-stained specimens. The tissue vasculature with blood flow is likely to have some effect during in vivo imaging, which is difficult to evaluate ex vivo. Animal studies using MPM imaging have similarly shown that there can be differences between the in vivo and ex vivo appearance of tissues (such as brain and lymph nodes).52,53 There is no method currently available, to our knowledge, to perform MPM imaging of the human gastrointestinal tract in vivo, so we are not yet able to determine the ways in which the esophageal mucosa changes appearance ex vivo. Another related issue is tissue degradation once it is removed from the body. Ultrastructural changes at the subcellular level start immediately after tissues are removed from the body, but it probably takes longer for light-microscopic changes to appear. Although we set a cut-off of 4 hours, based on the previous study,37 most of the tissues were imaged within 1 hour of procurement. The MPM images of endoscopic biopsies that are stored in this fashion and obtained within this interval do not undergo any visible degradation, as shown in the previous study.37 In this study, because we examined the same tissues by routine histology afterward, we can further confirm that there were no light-microscopic alterations identified when tissues were processed within 4 hours.

In conclusion, MPM has the ability to distinguish among the various types of tissues encountered at or around the GEJ at the level of histologic resolution and thus may help in the diagnosis of BE. Multiphoton microscopy imaging is a highly specific and sensitive method for the diagnosis of BE. In our limited study, MPM appeared superior to routine histology because it detected 3 cases of BE that were missed on standard H&E sections. This technology, however, appears to have some limitations (Table 3) that need further evaluation, as discussed above. Thus, in vivo diagnosis of BE tissue using MPM might lead to improved screening and surveillance of patients with BE. Moreover, this approach has the potential for a role not only in the diagnosis and monitoring of BE but also in real-time delineation of mucosal areas of concern during various ablative procedures for early neoplasia.

Table 3.

Comparison of Various Features Detected With Multiphoton Microscopy Imaging and Histology

| Features That Correlate Well Between MPM and Histology | Features That Do Not Correlate Well Between MPM and Histology |

|---|---|

| Squamous epithelium | Presence of inflammatory cells |

| Gastric glands (gastric cardia and oxyntic mucosa) | Details of connective tissue stroma |

| Presence of goblet cells | Nuclear details |

| Esophageal papillae | |

| Delineation of stroma |

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant 30970783 from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant IRT1115 from the Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University, and grants DK34989, DK57751, DK45710, and DK61747 from the National Institutes of Health. We thank Anish A. Sheth, MD, and Uzma D. Siddiqui, MD, for providing the biopsy samples from the patients.

Footnotes

The authors have no relevant financial interest in the products or companies described in this article.

References

- 1.Shaheen NJ, Richter JE. Barrett’s oesophagus. Lancet. 2009;373(9666):850–861. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60487-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spechler SJ. Clinical practice: Barrett’s esophagus. New Engl J Med. 2002;346(11):836–842. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp012118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lepage C, Rachet B, Jooste V, Faivre J, Coleman MP. Continuing rapid increase in esophageal adenocarcinoma in England and Wales. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(11):2694–2699. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pohl H, Welch HG. The role of overdiagnosis and reclassification in the marked increase of esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(2):142–146. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Portale G, Hagen JA, Peters JH, et al. Modern 5-year survival of resectable esophageal adenocarcinoma: single institution experience with 263 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;202(4):588–596. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.12.022. discussion 596–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Polednak AP. Trends in survival for both histologic types of esophageal cancer in US surveillance, epidemiology and end results areas. Int J Cancer. 2003;105(1):98–100. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stein HJ, Siewert JR. Barrett’s esophagus: pathogenesis, epidemiology, functional abnormalities, malignant degeneration, and surgical management. Dysphagia. 1993;8(3):276–288. doi: 10.1007/BF01354551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bird-Lieberman EL, Fitzgerald RC. Early diagnosis of oesophageal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;101(1):1–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reid BJ, Li X, Galipeau PC, Vaughan TL. Barrett’s oesophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma: time for a new synthesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(2):87–101. doi: 10.1038/nrc2773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas T, Abrams KR, De Caestecker JS, Robinson RJ. Meta analysis: cancer risk in Barrett’s oesophagus. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26(11–12):1465–1477. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moayyedi P, Burch N, Akhtar-Danesh N, et al. Mortality rates in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27(4):316–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma P, Weston AP, Topalovski M, Cherian R, Bhattacharyya A, Sampliner RE. Magnification chromoendoscopy for the detection of intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia in Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut. 2003;52(1):24–27. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.1.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kara MA, Ennahachi M, Fockens P, Kate FJW, Bergman JJ. Detection and classification of the mucosal and vascular patterns (mucosal morphology) in Barrett’s esophagus by using narrow band imaging. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64(2):155–166. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiesslich R, Goetz M, Burg J, et al. Diagnosing Helicobacter pylori in vivo by confocal laser endoscopy. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(7):2119–2123. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunbar KB, Canto MI. Confocal endomicroscopy. Tech Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;12(2):90–99. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo YT, Li YQ, Yu T, et al. Diagnosis of gastric intestinal metaplasia with confocal laser endomicroscopy in vivo: a prospective study. Endoscopy. 2008;40(7):547–553. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-995633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trovato C, Sonzogni A, Fiori G, et al. Confocal laser endomicroscopy for in vivo diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus and associated neoplasia: an ongoing prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67(5):AB97. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.03.104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kiesslich R, Gossner L, Goetz M, et al. In vivo histology of Barrett’s esophagus and associated neoplasia by confocal laser endomicroscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(8):979–987. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pohl H, Rösch T, Vieth M, et al. Miniprobe confocal laser microscopy for the detection of invisible neoplasia in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut. 2008;57(12):1648–1653. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.157461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunbar KB, Okolo P, III, Montgomery E, Canto MI. Confocal endomicroscopy in Barrett’s esophagus and endoscopically inapparent Barrett’s neoplasia: a prospective randomized double-blind controlled crossover trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70(4):645–654. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wallace MB, Meining A, Canto MI, et al. The safety of intravenous fluorescein for confocal laser endomicroscopy in the gastrointestinal tract. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31(5):548–552. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Canto MI. Endomicroscopy of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterol Clin of North Am. 2010;39(4):759–769. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2010.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Y, Liang CP, Liu Y, Fischer AH, Parwani AV, Pantanowitz L. Review of advanced imaging techniques. Journal of Pathology Informatics. 2012;3:22. doi: 10.4103/2153-3539.96751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsai TH, Zhou C, Lee HC, et al. Comparison of tissue architectural changes between radiofrequency ablation and cryospray ablation in Barrett’s esophagus using endoscopic three-dimensional optical coherence tomography. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:684832. doi: 10.1155/2012/684832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsai TH, Zhou C, Tao YK, et al. Structural markers observed with endoscopic 3-dimensional optical coherence tomography correlating with Barrett’s esophagus radiofrequency ablation treatment response (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76(6):1104–1112. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evans JA, Poneros JM, Bouma BE, et al. Optical coherence tomography to identify intramucosal carcinoma and high-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(1):38–43. doi: 10.1053/S1542-3565(05)00746-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bouma BE, Tearney GJ, Compton CC, Nishioka NS. High-resolution imaging of the human esophagus and stomach in vivo using optical coherence tomography. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51(4 pt 1):467–474. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(00)70449-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suter MJ, Vakoc BJ, Yachimski PS, et al. Comprehensive microscopy of the esophagus in human patients with optical frequency domain imaging. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68(4):745–753. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Squirrell JM, Wokosin DL, White JG, Bavister BD. Long-term two-photon fluorescence imaging of mammalian embryos without compromising viability. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17(8):763–767. doi: 10.1038/11698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centonze VE, White JG. Multiphoton excitation provides optical sections from deeper within scattering specimens than confocal imaging. Biophys J. 1998;75(4):2015–2024. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77643-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhuo SM, Zheng LQ, Chen JX, Xie SS, Zhu XQ, Jiang XS. Depth-cumulated epithelial redox ratio and stromal collagen quantity as quantitative intrinsic indicators for differentiating normal, inflammatory, and dysplastic epithelial tissues. Appl Phys Lett. 2010;97:173701. doi: 10.1063/1.3505762. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koehler MJ, König K, Elsner P, Buckle R, Kaatz M. In vivo assessment of human skin aging by multiphoton laser scanning tomography. Opt Lett. 2006;31(19):2879–2881. doi: 10.1364/ol.31.002879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun TL, Liu Y, Sung MC, et al. Ex vivo imaging and quantification of liver fibrosis using second-harmonic generation microscopy. J Biomed Opt. 2010;15(3):036002. doi: 10.1117/1.3427146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin SJ, Jee SH, Kuo CJ, et al. Discrimination of basal cell carcinoma from normal dermal stroma by quantitative multiphoton imaging. Opt Lett. 2006;31(18):2756–2758. doi: 10.1364/ol.31.002756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhuo S, Chen J, Wu G, et al. Quantitatively linking collagen alteration and epithelial tumor progression by second harmonic generation microscopy. Appl Phys Lett. 2010;96:213704. doi: 10.1063/1.3441337. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen J, Zhuo S, Chen G, et al. Establishing diagnostic features for identifying the mucosa and submucosa of normal and cancerous gastric tissues by multiphoton microscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73(4):802–807. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rogart JN, Nagata J, Loeser CS, et al. Multiphoton imaging can be used for microscopic examination of intact human gastrointestinal mucosa ex vivo. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(1):95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paull A, Trier JS, Dalton MD, Camp RC, Loeb P, Goyal RK. The histologic spectrum of Barrett’s esophagus. New Engl J Med. 1976;295(9):476–480. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197608262950904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang KS, Sampliner RE Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Updated guidelines 2008 for the diagnosis, surveillance and therapy of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(3):788–797. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.König K. Clinical multiphoton tomography. Journal of Biophotonics. 2008;1(1):13–23. doi: 10.1002/jbio.200710022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.König K, Ehlers A, Riemann I, Schenkl S, Buckle R, Kaatz M. Clinical two-photon microendoscopy. Microsc Res Tech. 2007;70(5):398–402. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jung JC, Schnitzer MJ. Multiphoton endoscopy. Opt Lett. 2003;28(11):902–904. doi: 10.1364/ol.28.000902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Flusberg BA, Jung JC, Cocker ED, Anderson EP, Schnitzer MJ. In vivo brain imaging using a portable 3.9 gram two-photon fluorescence microendoscope. Opt Lett. 2005;30(17):2272–2274. doi: 10.1364/ol.30.002272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gobel W, Kerr JN, Nimmerjahn A, Helmchen F. Miniaturized two-photon microscope based on a flexible coherent fiber bundle and a gradient-index lens objective. Opt Lett. 2004;29(21):2521–2523. doi: 10.1364/ol.29.002521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Engelbrecht CJ, Johnston RS, Seibel EJ, Helmchen F. Ultra-compact fiber-optic two-photon microscope for functional fluorescence imaging in vivo. Opt Express. 2008;16(8):5556–5564. doi: 10.1364/oe.16.005556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fu L, Jain A, Cranfield C, Xie H, Gu M. Three-dimensional nonlinear optical endoscopy. J Biomed Opt. 2007;12(4):040501. doi: 10.1117/1.2756102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tang S, Jung W, McCormick D, et al. Design and implementation of fiber-based multiphoton endoscopy with microelectromechanical systems scanning. J Biomed Opt. 2009;14(3):034005. doi: 10.1117/1.3127203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Myaing MT, MacDonald DJ, Li X. Fiber-optic scanning two-photon fluorescence endoscope. Opt Lett. 2006;31(8):1076–1078. doi: 10.1364/ol.31.001076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goldblum JR. Controversies in the diagnosis of Barrett esophagus and Barrett-related dysplasia: one pathologist’s perspective. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134(10):1479–1484. doi: 10.5858/2010-0249-RA.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Skala MC, Squirrell JM, Vrotsos KM, et al. Multiphoton microscopy of endogenous fluorescence differentiates normal, precancerous, and cancerous squamous epithelial tissues. Cancer Res. 2005;65(4):1180–1186. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Theer P, Hasan MT, Denk W. Two-photon imaging to a depth of 1000 micron in living brains by use of a Ti:Al2O3 regenerative amplifier. Opt Lett. 2003;28(12):1022–1024. doi: 10.1364/ol.28.001022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen X, Leischner U, Rochefort NL, Nelken I, Konnerth A. Functional mapping of single spines in cortical neurons in vivo. Nature. 2011;475(7357):501–505. doi: 10.1038/nature10193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Germain RN, Robey EA, Cahalan MD. A decade of imaging cellular motility and interaction dynamics in the immune system. Science. 2012;336(6089):1676–1681. doi: 10.1126/science.1221063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]