Abstract

exo-Methylene lactone group-containing compounds, such as (−)-xanthatin, are present in a large variety of biologically active natural products, including extracts of Xanthium strumarium (Cocklebur). These substances are reported to possess diverse functional activities, exhibiting anti-inflammatory, antimalarial, and anticancer potential. In this study, we synthesized six structurally related xanthanolides containing exo-methylene lactone moieties, including (−)-xanthatin and (+)-8-epi-xanthatin, and examined the effects of these chemically defined substances on the highly aggressive and farnesyltransferase inhibitor (FTI)-resistant MDA-MB-231 cancer cell line. The results obtained demonstrate that (−)-xanthatin was a highly effective inhibitor of MDA-MB-231 cell growth, inducing caspase-independent cell death, and that these effects were independent of FTase inhibition. Further, our results show that among the GADD45 isoforms, GADD45γ was selectively induced by (−)-xanthatin and that GADD45γ-primed JNK and p38 signaling pathways are, at least in part, involved in mediating the growth inhibition and potential anticancer activities of this agent. Given that GADD45γ is becoming increasingly recognized for its tumor suppressor function, the results presented here suggest the novel possibility that (−)-xanthatin may have therapeutic value as a selective inducer of GADD45γ in human cancer cells, in particular in FTI-resistant aggressive breast cancers.

INTRODUCTION

exo-Methylene lactone group-containing compounds are present ubiquitously in a large variety of biologically active natural products,1 including extracts of Xanthium strumarium (Cocklebur), and possess diverse activities, including anti-inflammatory, antimalarial, and cytotoxic activities for cancer cells.1 Although the xanthanolides are potentially attractive anticancer candidates, X. strumarium contains only trace amounts of the xanthanolide sesquiterpene lactones. It has been reported that natural product extracts that contain principally (+)-8-epi-xanthatin and (−)-xanthatin (see Figure 1) are effective growth inhibitors of several human tumor cell lines, with IC50 values ranging from 0.8 to 6.1 µM, and that farnesyltransferase (FTase) is a potential target of (+)-8-epi-xanthatin, exhibiting an IC50 value of 64 µM.2 FTase catalyzes post-translational prenylation reactions that are required for the oncogenic properties of certain GDP/GTP-binding GTPases, including Ras and Rho. 3,4 Although there is an apparent inconsistency in the reported IC50 values for (+)-8-epi-xanthatin-mediated inhibition of FTase activity versus its effect on cancer cell growth rates, FTase inhibition may be a mechanistic target of this agent’s growth suppression. It is noteworthy that (+)-8-epi-xanthatin has never been evaluated for its effects in human breast cancer-derived cells. Nor is there detailed experimental information investigating the effects of pure, chemically synthesized derivatives of (+)-8-epi-xanthatin or (−)-xanthatin on any human cancer cell lines, as previous studies have relied upon the use of cruder biological extracts.

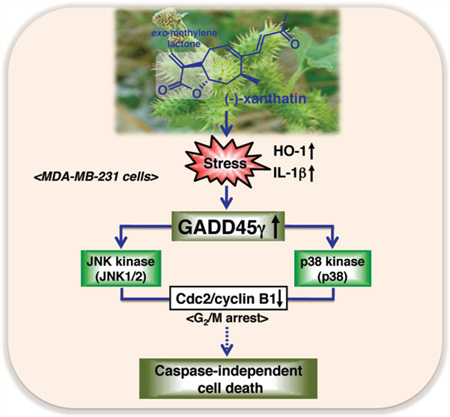

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of six synthesized xanthanolide sesquiterpene lactones and β-caryophyllene and IC50 values for MDA-MB-231 cell growth inhibition. The exo-methylene lactone moiety, indicated with a gray inclusion, but not the dienone moiety (with a dotted line enclosure) is suggested as important for (−)-xanthatin- and (+)-8-epi-xanthatin-mediated inhibitory effects on MDA-MB-231 cell growth. Inset: MDA-MB-231 cells were exposed to increasing concentrations of compounds listed in the figure. The IC50 values (µM), obtained at 48 h in culture, were determined as described in Materials and Methods. The values indicate the means of three independent experiments performed with five technical replicates. Except for (−)-xanthatin and (+)-8-epi-xanthatin, IC50 values could not be determined due to weak inhibitory activities. The figures in parentheses indicate the percent of cell viability when compared with that of the vehicle-treated group (control as 100%).

The molecular mechanisms of breast cancer progression and metastasis are not fully understood.5−13 Among experimental human breast cancer cell lines, MDA-MB-231 cells have been established as a valuable model for preclinical studies as they are highly aggressive, both in vitro and in vivo. 7,14 Further, MDA-MB-231 cells have been characterized as farnesyltransferase-inhibitor (FTI) “resistant” cells.15,16 However, there is no information regarding the sensitivity of these cells to xanthanolide sesquiterpene lactone-mediated growth inhibition, such as for (+)-8-epi-xanthatin and (−)-xanthatin.

Another increasingly recognized target in cancer biology is the growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible gene 45 (GADD45) pathway, inducible by a variety of DNA damaging agents, such as UV irradiation and methylmethane sulfonate.17 While GADD45 was initially identified as a gene rapidly induced by stimuli and assigned a role as a stress sensor,17 more recent attention has focused on GADD45 as a likely tumor suppressor gene that is inactivated in multiple tumor types.18 GADD45 stimulation results in the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling, including the p38 MAPK and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathways.19–21 In these respects, it is note-worthy that compounds containing a sesquiterpene lactone moiety can modulate MAPK pathways through the induction of cellular stress,1 although the details of this mechanism are not well established. To date, at least three major MAPK pathways, extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2 (ERK1/2), JNK, and p38, are recognized as physiologically important,19,21 undergoing activation by various stimuli, including UV irradiation, oxidation, and treatments with anticancer chemicals.21,22 The JNK and p38 signaling pathways appear particularly responsive to stress stimuli.19,20 Although an interplay in the apoptotic process has been established between the induction of GADD45 and the activation of stress stimuli-mediated p38/JNK signaling pathways,19 GADD45 pathways themselves have not been investigated as potential mediators of the cancer cell growth inhibitory effects exhibited by the xanthanolide sesquiterpene lactones.

In the current study, we chemically synthesized six structurally related xanthanolides-containing exo-methylene lactones, including (−)-xanthatin and (+)-8-epi-xanthatin, and examined their activities on MDA-MB-231 cancer cells. The results revealed that (i) (−)-xanthatin possesses the most efficacious antiproliferation potential, demonstrated by the induction of caspase-independent death in MDA-MB-231 cells, and that (ii) the effect of (−) -xanthatin appears independent of FTase inhibition. Further, our results show that among the GADD45 isoforms, GADD45γ is selectively induced by (−) -xanthatin through cellular stress pathways including oxidative stress and that GADD45γ-primed JNK and p38 signaling pathways are, at least in part, involved in mediating (−)-xanthatin’s growth inhibition and potential anticancer activities.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Of the six xanthanolides used in this study, (−)-xanthatin, (+)-8-epi-xanthatin, and (−)-dihydroxanthatin were chemically synthesized according to a published protocol.23 The remaining compounds including xanthocidin derivatives were synthesized according to our previously established methods.24−26 These synthesized compounds were purified by HPLC or column chromatography, and their purity (>95%) was confirmed by 1H- and 13C NMR spectroscopy. No ring-opened derivatives of the xanthanolides’ lactones were detected in our analyses. β-Caryophyllene/SP600125/d-limonene and FTI-277/U0126 were purchased from Sigma Co. (St. Louis, MO) and Calbiochem (San Diego, CA), respectively. SB202190 and Z-VAD-FMK were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd. (Osaka, Japan) and Enzo Life Sciences International, Inc. (Farmingdale, NY), respectively. (−)-Perillic acid was purchased from Axxora LLC (San Diego, CA). N-Acetyl-L-cysteine and L-ascorbic acid (vitamin C) were purchased from Nacalai Tesque Inc. (Kyoto, Japan). All other reagents were of the highest grade commercially available.

Cell Cultures and Proliferation Assays

Cell culture conditions and methods were based on procedures described previously.12,13 Briefly, the human breast cancer cell lines, MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 (obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD), were routinely grown in phenol red-containing minimum essential medium alpha (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), supplemented with 10 mM HEPES, 5% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL of penicillin, and 100 µg/mL of streptomycin in a humidified incubator, in an atmosphere of 5% CO2, at 37 °C. Before chemical treatments, the medium was changed to phenol red-free minimum essential medium alpha (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10 mM HEPES, 5% dextran-coated charcoal-treated serum, 100 U/mL of penicillin, and 100 µg/mL of streptomycin. Cultures of approximately 60% confluence in a 100-mm Petri dish were used to seed the proliferation experiments. In the proliferation studies, the cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of approximately 5,000 cells/well, and test substances were introduced 4 h after cell seeding. After 24 or 48 h of incubation, cell proliferation was analyzed using a reagent of CellTiter 96 Aqueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay (MTS reagent; Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All test chemicals were prepared in ethanol. Control incubations contained equivalent additions of ethanol. No adverse influence of ethanol was detectable on cell viability at the final concentrations used.

Assay of Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) Secretion

The CytoTox96 non-Radioactive Cytotoxicity Assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI) was used to quantitatively measure LDH, a stable cytosolic enzyme that is released in necrosis. MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with (−)-xanthatin and (−)-dihydroxanthatin at 0.5−25 µM for 24 or 48 h, and then released LDH levels were determined.

Cell Morphology Studies

For morphological examination of MDA-MB-231 cells after treatments, images were obtained using an inverted microscope Leica DMIL (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar) and captured using a Pixera Penguin 600CL Cooled CCD digital camera (Pixera Co., Los Gatos, CA). For dual treatments with (−)-xanthatin and inhibitor, each inhibitor (U0126, SP600125, SB202190, or Z-VAD-FMK) was pretreated for 2 h, and then (−)-xanthatin was introduced into the culture. Exposure to the inhibitors did not result in any remarkable effects in cell morphology. The concentrations of inhibitors used in the experiments were determined empirically following dose-response measures of their relative effectiveness. Data were processed using Pixera Viewfinder 3.0 software (Pixera Co., Los Gatos, CA). The breast cancer cells were plated in 6-well plates. Three areas with approximately equal cell densities were identified in each well, and images of each of these areas were captured.

Analysis of p21WAF1/CIP1 (p21), IL-1β, HO-1,GADD45α/β/γ, Cdc2, and Cyclin B1 mRNA by Semiquantitative Reverse Transcription–Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was prepared from MDA-MB-231 cells using RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Inc. Hilden, Germany) and was purified using RNeasy/QIAamp columns (Qiagen, Inc. Hilden, Germany), and the following cDNA (cDNA) synthesis, RT and PCR were performed using SuperScript One-Step RT-PCR System with Platinum Taq polymerase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The primers used were p21 (sense) 5′-GTG AGC GAT GGA ACT TCG ACT T-3′ and p21 (antisense) 5′-GGC GTT TGG AGT GGT AGA AAT C-3′. The primers used were IL-1β (sense) 5′-CAG CTA CGA ATC TCC GAC CA-3′ and IL-1β (antisense) 5′-ACT TGT TGC TCC ATA TCC TGT-3′. The primers used were HO-1 (sense) 5′-CGC CTA CAC CCG CTA CCT G-3′ and HO-1 (antisense) 5′-TTG GCC TCT TCT ATC ACC CTC-3′. The primers used were GADD45α (sense) 5′-AAC ATC CTG CGC GTC AGC AA-3′ and GADD45α (antisense) 5′-CCC ATT GAT CCA TGT AGC GAC T-3′. The primers used were GADD45β (sense) 5′-CAA GTT GAT GAA TGT GGA CCC-3′ and GADD45β (antisense) 5′-CTT TCT TCG CAG TAG CTG G-3′, and GADD45γ (sense) 5′-CAA AGT CTT GAA CGT GGA CCC-3′ and GADD45γ (antisense) 5′-GAT CCT TCC AGG CGT CCT C-3′. The primers used were Cdc2 (sense) 5′-TCA GTC TTC AGG ATG TGC TT-3′ and Cdc2 (antisense) 5′-GCAAAT ATG GTG CCT ATACTC C-3′. The primers used were cyclin B1 (sense) 5′-CCA TTA TTG ATC GGT TCA TGC3′ and cyclin B1 (antisense) 5′-GCC AAA GTA TGT TGC TCG AC-3′. Primers for PCR of β-actin were taken from previously published work.27 PCR of p21, IL-1β, HO-1, GADD45α/β/γ, Cdc2, cyclin B1, and β-actin was performed under conditions producing template quantity-dependent amplification over 33 cycles. Details of the PCR conditions are indicated in the Figure legends. PCR products were separated by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis in Tris-acetate EDTA buffer and stained with ethidium bromide. When the RT reaction was omitted, no signal was detected in any of the samples. β-Actin was used as an internal control for RT-PCR.

DNA Microarray Analysis

Total RNA was collected from 10 µM (−)-xanthatin or vehicle-treated MDA-MB-231 cells 48 h after exposure by using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Inc. Hilden, Germany) and was purified using RNeasy/QIAamp columns (Qiagen, Inc. Hilden, Germany). The specific gene expression pattern in the MDA-MB-231 cells was examined by DNA microarray analysis in comparison with vehicle-controls. From both cells, total RNA was extracted, and cDNA synthesizing and cRNA labeling were conducted using a Low RNA Fluorescent Linear Amplification kit (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA). Labeled cRNA (Cy3 to controls, Cy5 to (−)-xanthatins) was hybridized to human oligo DNA microarray slides (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA) that carry spots for human genes. Specific hybridization was analyzed using a Microarray scanner (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA) and evaluated as a scatter-plot graph for gene expression. Hokkaido System Science (Sapporo, Japan) provided assistance with experiments.

DNA Fragmentation Analysis

DNA fragmentation analysis, an indicator of apoptosis, was performed using the commercial Suicide Track DNA ladder isolation kit (Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany), according to the manufacturing procedure provided.

Relaxation Assay of DNA Topoisomerase I (Topo I)

Topo I and pBR322 DNA (supercoiled DNA) were purchased from TaKaRa Bio Inc. (Kyoto, Japan) and New England Biolabs Inc. (Ipswich, MA). The enzyme reaction was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (TaKaRa Bio Inc.).

Data Analysis

IC50 values were determined using SigmaPlot 11 software (Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA), according to analyses described previously.28−31 Differences were considered significant when the p value was calculated as less than 0.05. Statistical differences between two groups were calculated by the Student’s t test. Other statistical analyses were performed by Scheffe’s F test, a post-hoc test for analyzing results of ANOVA testing. These calculations were performed using Statview 5.0J software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Effects of Xanthanolides on the Proliferation of MDA-MB-231 Cells

We investigated the effects of six chemically synthesized xanthanolides (Figure 1) on the proliferation of MDA-MB-231 cells in culture. (−)-Xanthatin and (+)-8-epi-xanthatin were revealed as effective inhibitors of MDA-MB-231 cell proliferation. The IC50 values after 48 h of exposure to (−)-xanthatin and (+)-8-epi-xanthatin were 5.28 µM and 10.57 µM, respectively (Figure 1, inset). Complete inhibition of cell growth was observed at 25 µM with (−)-xanthatin and (+)-8-epi-xanthatin following treatment for 48 h (Figure 2A, right panel). In comparison, the other synthesized xanthanolides exhibited no observable effects on the growth of MDA-MB-231 cells, even at 25 µM (Figures 1 and 2A). In particular, (−)-dihydroxanthatin, a reduced form of (−)-xanthatin (see Figure 1), did not exert inhibitory effects on cellular proliferation (Figures 1 and 2A). In addition to an exo-methylene lactone moiety, (−)-xanthatin contains a dienone group (see Figure 1), a potentially reactive/electrophilic functional group, capable of Michael-type adduct formation with DNA bases and other molecules.32 However, due to its lack of antiproliferative activity, it appears that this moiety does not contribute to essential antiproliferative properties of the xanthanolides. Further, the exo-methylene-containing β-caryophyllene was largely inactive with respect to exerting antiproliferative activity on MDA-MB-231 cells (Figures 1, inset, and 2A). Together, these results suggest that the exo-methylene structure containing a lactone moiety is the key determinant for the (−)-xanthatin-mediated effects (see Figure 1, indicated with gray inclusion in the structures). Interestingly, both (−)-xanthatin and (+)-8-epi-xanthatin abrogated MDA-MB-231 cell viability in a time- and dose-dependent manner (Figure 2A); however, (−)-xanthatin inhibited cell proliferation with a 2-fold stronger efficacy than that of (+)-8-epi-xanthatin (Figures 1 and 2A). These results directed our further focus on the (−)-xanthatin-mediated antiproliferative effects on MDA-MB-231 cells.

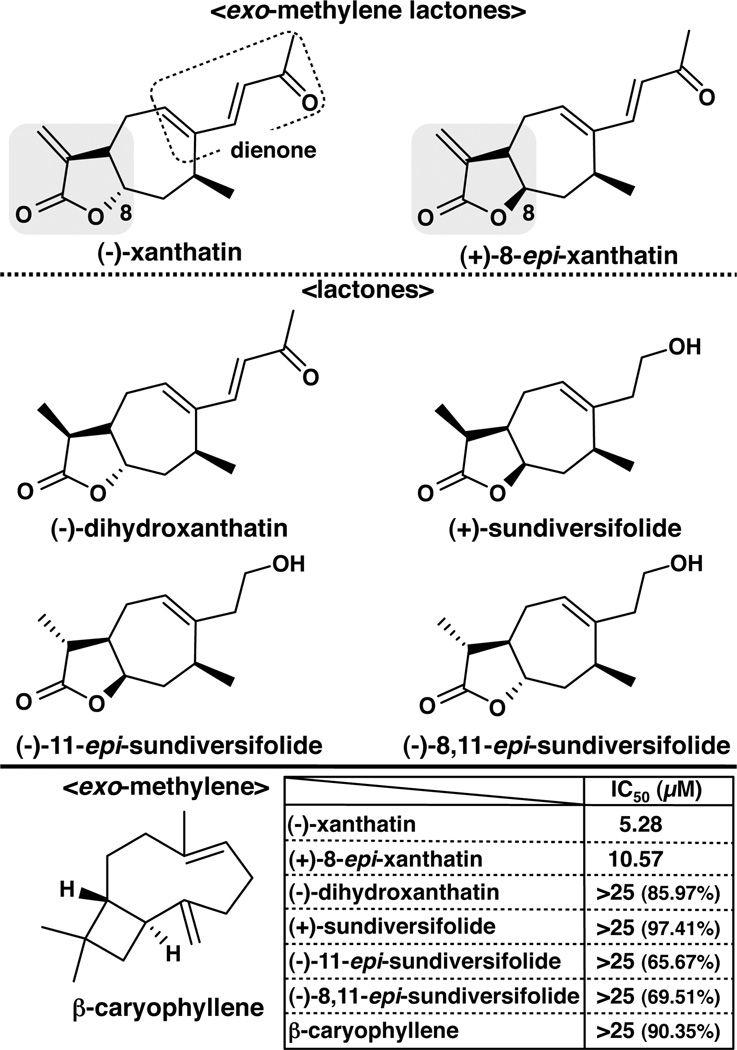

Figure 2.

(−)-Xanthatin inhibits the growth of MDA-MB-231 cells in a dose- and time-dependent manner. (A) MDA-MB-231 cells were exposed for 24 h (left panel) or 48 h (right panel) to increasing concentrations of the compounds indicated in Figure 1. Data are expressed as the percent of the vehicle-treated group (control) and represent the mean ± SD (n = 5). *Significantly different (p < 0.05) from control. Cont, control; Dihy, (−)-dihydroxanthatin; and BCP, β-caryophyllene. N.D., not detectable (because of complete cell death). (B) MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with vehicle (a; control), 25 µM (−)-dihydroxanthatin (b), and 10 and 25 µM (−)-xanthatin (c and d, respectively) for 48 h prior to the examination of cellular morphology. Representative data images are shown. Images were taken with × 100 magnification (a, b, c, and d). (C) LDH released into the culture medium was measured at 24 or 48 h after the indicated concentrations of (−)-xanthatin/(−) -dihydroxanthatin treatments. Data are expressed as the percent of vehicle-treated group (control) and represent the mean ± SD (n = 5). *Significantly different (p < 0.05) from the control. **Significantly different (p < 0.05) from 10 µM (−)-xanthatin-treated groups at 24 or 48 h. (D) Cells were exposed to 10 µM (−)-xanthatin for 2 or 48 h, and the morphology of cells was assessed at high resolution (a, control for 2 h; b, control for 48 h; c, xanthatin for 2 h; d, xanthatin for 48 h).

Morphological Alterations and Cell Membrane Integrities in MDA-MB-231 Cells after (−)-Xanthatin Treatment

MDA-MB-231 cells displayed typical mesenchymal morphology at 48 h (Figure 2B, control panel a). However, treatments with (−)-xanthatin resulted in a striking and dose-dependent morphological change in MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 2B, panel a vs c and d). Specifically, increasing concentrations of (−)-xanthatin resulted in a progressively more rounded cellular appearance (Figure 2B;0.05–5 µM, data not shown). In contrast, treatment with 25 µM (−)-dihydroxanthatin was devoid of noticeable effects on cellular morphology (Figure 2B, panel b).

To investigate the loss of plasma membrane integrity, a property associated with necrosis, the LDH release assay was used as a measure of cell lysis after (−)-xanthatin treatment (Figure 2C). Although high concentrations of (−)-xanthatin (25 µM) induced significant release of LDH in a time-dependent manner, untreated cells (i.e., spontaneous LDH release), cells treated with 0.5–5 µM (−)-xanthatin or 0.5–25 µM (−)-dihydroxanthatin, exhibited little detectable LDH release, even after 48 h of exposure. For further confirmation of these results, high resolution microscopic analysis was performed (Figure 2D). When compared to the vehicle-treated control (Figure 2D, panel a), plasma membrane blebbing was observed 2 h after treatment with (−)-xanthatin (panel c). In good agreement with the LDH release assays, cell membrane rupture was not detected 48 h after 10 µM (−)-xanthatin exposure (panel d), although the agent-treated cells showed a quite different morphology compared to that of the cells treated by vehicle alone (panel b). Also, subsequent to (−)-xanthatin removal (i.e., 25 µM for 48 h treatment), cell viability was not restored following incubation (data not shown), suggesting that (−)-xanthatin can suppress the proliferation of MDA-MB-231 cells, followed by necrotic cell death, or cytotoxic cell death at higher concentrations of (−)-xanthatin (>25 µM). On the basis of these lines of evidence, 10 µM (−)-xanthatin levels were chosen for further mechanistic experiments.

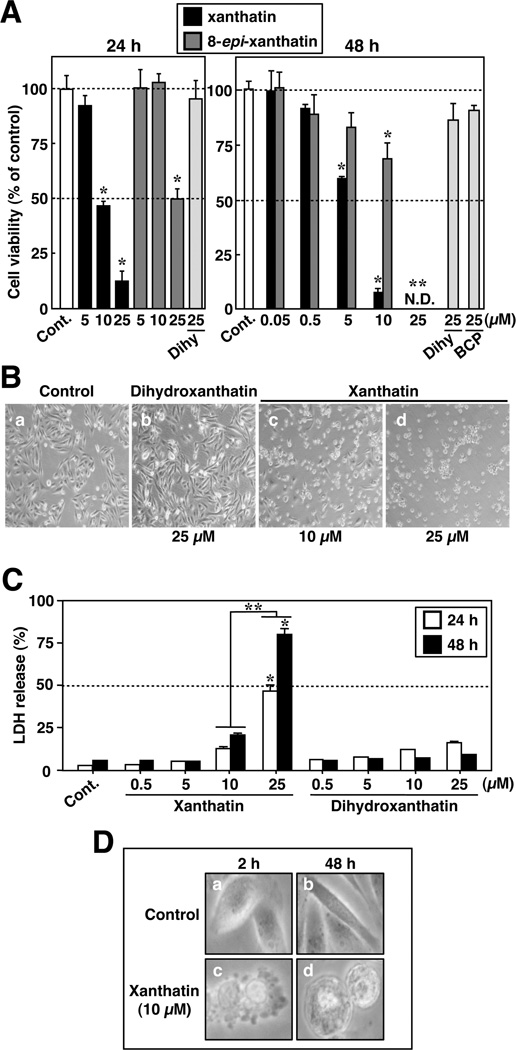

Stress-Responsible Genes IL-1β and HO-1, but Not the FTI-Sensitive p21 Gene, Are Induced by (−)-Xanthatin

It has been suggested that (+)-8-epi-xanthatin, an analogue of (−)-xanthatin, may suppress the proliferation of some tumor cells via FTase inhibition.2 We therefore hypothesized that if (−)-xanthatin exerts its antiproliferative action on the malignant cells through FTase inhibition, FTI-resistant MDA-MB-231 cells should not be influenced by this agent. To test this hypothesis, we first examined whether FTI-277, a highly potent and selective inhibitor of FTase,33 can affect MDA-MB-231 cell growth. Although MDA-MB-231 cells express functional FTase,34 the cells were markedly resistant to FTI-277, even at 25 µM concentrations (Figure 3A), a concentration much higher than the reported IC50 value of 100 nM.33 Therefore, if (−)-xanthatin and (+)-8-epi-xanthatin specifically target FTase activity, MDA-MB-231 cells should be resistant to these agents as well. However, the proliferative activity of the FTI-resistant breast cancer cells was inhibited potently by (−)-xanthatin in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 3A; also see Figure 2A). MDA-MB-231 cell resistance to FTI-277 treatment has also been reported by others.15,16 In addition, other known FTase inhibitory compounds explored for use as anticancer agents, d-limonene and perillic acid,35,36 did not abolish the proliferation of MDA-MB-231 cells (i.e., IC50 values >25 µM, respectively) (data not shown). Further, it was reported that FTIs can induce the expression of the p21 gene, an important cell-cycle suppressor.37,38 If this mechanistic target was conserved for (−) -xanthatin, then the respective expression level of this suppressor would be expected to be positively stimulated by (−)-xanthatin treatment. However, no enhancement of p21 gene transcript level was detected following (−)-xanthatin treatment (Figure 3B, inset). Therefore, the data presented here strongly support the idea that the mechanism of the (−)-xanthatin-mediated antiproliferative effects on MDA-MB-231 cells is distinct from that of FTase inhibition.

Figure 3.

(−)-Xanthatin-mediated growth suppression of MDA-MB-231 cells is accompanied by elevations in stress-responsive gene expression but not p21. (A) MDA-MB-231 cells were exposed for 48 h to increasing concentrations of FTI-277 (0.05−25 µM) and (−)-xanthatin (5 and 10 µM). Data are expressed as the percent of vehicle-treated group (control), as mean ± SD (n = 5). *Significantly different (p < 0.05) from the control. **Significantly different (p < 0.05) from the 10 µM FTI-277-treated group. N.S., not significant. (B) RT-PCR analysis of p21 mRNA levels after treatment with (−)-xanthatin at 10 µM. β-Actin was used as an RNA normalization control. Lane 1, 100-bp DNA ladder marker; lanes 2 and 4, mRNA levels in the absence of (−)-xanthatin; and lanes 3 and 5, mRNA levels in the presence of (−)-xanthatin. p21 mRNA level was not influenced by (−)-xanthatin (see inset; see also Figure 4A–a). A representative data image is shown. (C) RT-PCR analysis of IL-1β and HO-1 mRNAlevels after treatment with 10 µM (−)-xanthatin. β-Actin was used as an RNA normalization control. Lanes 1 and 6,100-bp DNA ladder marker; lanes 2,4, 7, and 9, mRNAlevels in the absence of (−)-xanthatin; and lanes 3, 5, 8, and 10, mRNAlevels in the presence of (−)-xanthatin up-regulated transcript levels for the stress responsive genes, IL-1β and HO-1. A representative data image is shown. (D) MDA-MB-231 cells were treated for 48 h with 5 µM or 10 µM(−)-xanthatin in the presence (+) or absence (−) of two antioxidants, vitamin C (Vit.C) and N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC), respectively. Each inhibitor was added (Vit.C, 25 µM; NAC, 1 mM, respectively) as a pretreatment, 2 h in advance to (−)-xanthatin additions. Data are expressed as the percent of vehicle-treated group (−/−/− group), as the mean ± SD (n = 5). *Significantly different (p < 0.05) from the control. **Significantly different (p < 0.05) from the 5 µM (−)-xanthatin alone-treated group. ***Significantly different (p < 0.05) from the 10 µM (−)-xanthatin alone-treated group.

Therefore, the question remains as to how (−)-xanthatin exerts its antiproliferative actions on the breast cancer cells. It is accepted that sesquiterpene compounds containing the exo-methylene lactone can interact with cysteine residue(s) in proteins involved in maintaining the redox balance in cells, via a Michael-type addition.1 These interactions in turn disrupt intracellular redox balance, leading to concomitant induction of interleukin-1β (IL-1β), heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) expression, and activation of reactive oxygen species. 1,39,40 If the lactone moiety of (−)-xanthatin is responsible for the bioactivity, it would be expected that the expression of IL-1β and HO-1 would be up-regulated by the respective treatment. Thus, we investigated the mRNA expression status of IL-1β and HO-1 after the chemical treatment. IL-1β expression was increased 3.0-fold (Figure 3C, left panel), and HO-1 was similarly up-regulated 5.3-fold (Figure 3C, right panel). Further, the (−)-xanthatin-mediated antiproliferative effects on MDA-MB-231 cells were suppressed by treatments with two types of antioxidants: N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) and vitamin C (Vit.C), with NAC more effective than Vit.C at either 5 or 10 µM (−)-xanthatin treatments (Figure 3D). These data suggest that (−)-xanthatin may suppress MDA-MB-231 cell growth through the modulation of intracellular oxidative stress pathways.

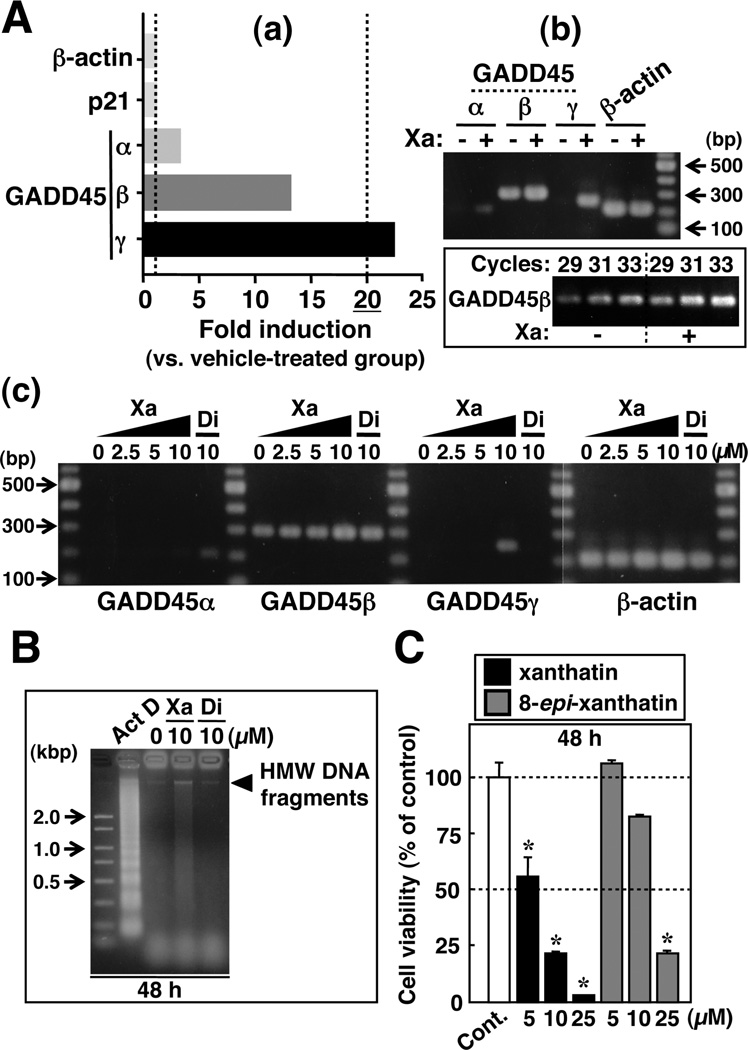

GADD45γ mRNA Overexpression Selectively Induced by (−)-Xanthatin

To indentify the pathways responsible for the (−)-xanthatin-induced breast cancer-suppressive effects, we performed gene expression/microarray experiments. Among the various genes that were up-regulated by 10 µM (−)-xanthatin treatments, the GADD45α/β/γ gene family was noteworthy. Of these transcripts, GADD45γ expression exhibited the most marked up-regulation (22.2-fold), followed by GADD45β (13-fold) (Figure 4A–a). As shown in the Figure 4A–b, we verified the results of the DNA microarray using RT-PCR methodology. GADD45Cα and GADD45β transcript levels were modestly increased, whereas levels of GADD45γ were clearly up-regulated in the (−)-xanthatin-treated group. It should be noted that although p21, IL-1β, and HO-1 genes were basally expressed in the MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 3, panels B and C), the GADD45γ gene was largely suppressed in the absence of treatment (Figure 4A–b). Again, no up-regulation of p21 expression was detected by the DNA microarray analysis (Figure 4A–a, see also Figure 3B), although up-regulation of the IL-1β and HO-1 genes was observed (4.9- and 3.9-fold, respectively). Collectively these results indicate that (−)-xanthatin modulates GADD45 gene levels in FTI-resistant MDA-MB-231 tumor cells. Of interest, treatment of the cell cultures with the inactive congener, (−)-dihydroxanthatin (see Figures 1 and 2), resulted in apparent up-regulation of GADD45Cα and GADD45β as well; however, GADD45γ expression was specifically enhanced only in the 10 µM (−)-xanthatin-treated samples (Figure 4A–c). Although GADD45β expression was only modestly more sensitive to (−)-xanthatin treatment than (−)-dihydroxanthatin (Figure 4A, panel b and c), perhaps GADD45β up-regulation also positively enhances the functional activities of (−) -xanthatin in MDA-MB-231 cells. The marked induction response of GADD45γ to (−)-xanthatin treatments correlated well with the degree of cell death induced by this agent (Figure 2A, right panel), implicating GADD45γ as a selective target of (−)-xanthatin’s functional effects in MDA-MB-231 cells.

Figure 4.

Selective up-regulation of the GADD45γ gene and its downstream signaling pathways are modulated by (−)-xanthatin. (A-a) Results of DNAmicroarray analysis. Data are expressed as fold induction vs vehicle-treated groups. MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with the vehicle or 10 µM (−)-xanthatin for 48 h, followed by mRNA isolation. Details of microarray conditions are described under Materials and Methods. (A-b) RT-PCR analysis of GADD45 isoform α/β/γ transcript levels after treatment with (+) or without (−) 10 µM (−)-xanthatin. β-Actin was used as an RNA normalization control. A 100-bp DNA ladder marker was also loaded. Xa, (−)-xanthatin. A representative data image is shown. Also see also the inset (GADD45β). (A-c) RT-PCR analysis of GADD45 isoform α/β/γ mRNA levels after treatment with varying concentrations of (−)-xanthatin, ranging from 2.5 to 10 µM, and 10 µM (−)-dihydroxanthatin. β-Actin was used as an RNA normalization control. A 100-bp DNA ladder marker was also loaded. Xa, (−)-xanthatin; and Di, (−)-dihydroxanthatin. A representative data image is shown. (B) DNA fragmentation analysis after 10 µM (−)-xanthatin or 10 µM (−)-dihydroxanthatin treatments for 48 h. Actinomycin D (Act D) was used as a positive control for DNA fragmentation. A DNA size marker was also loaded. Xa, (−)-xanthatin; and Di, (−)-dihydrox-anthatin. A representative data image is shown. (C) MCF-7 cells were exposed for 48 h to increasing concentrations of (−)-xanthatin or (+)-8-epi-xanthatin as indicated in the Figure. Data are expressed as the percent of the vehicle-treated group (control) and represent the mean ± SD (n = 5). *Significantly different (p < 0.05) from the control. Cont, control.

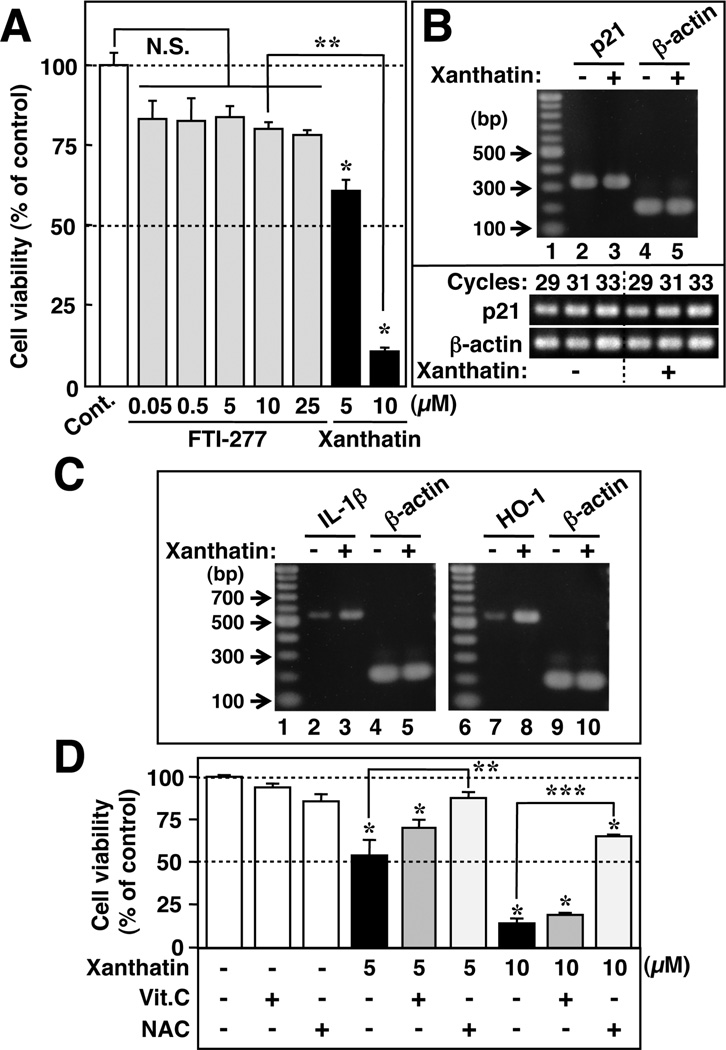

GADD45γ-Related Signaling Pathways Are Involved in (−)-Xanthatin-Mediated Cell Death

We next assessed the downstream pathways of GADD45 activation. Since GADD45γ is capable of modulating each of the stress-responsive JNK and p38 signaling pathways in the cell death pathway,19−21 we tested established inhibitors of JNK (SP600125), p38 (SB202190) and ERK (U0126) for their respective effects on (−)-xanthatin-mediated morphological change as well as on cell death. (−)-Xanthatin treatment resulted in the loss of the characteristic spindle-shape in MDA-MB-231 cells and adoption of a rounded cellular morphology, followed by cell death (see Figure 2B, panels a vs c/d and Figure 2D). When comparing (−)-xanthatin-induced cell death [i.e., (%) inhibition of cell viability, 85.43 ± 6.52%] and the accompanying morphological changes induced (data not shown), both parameters were effectively blocked by pretreatments of either 10 µM SP600125 or 10 µM SB202190 for 2 h [i.e., (%) inhibition of cell viabilities, SP600125 = 40.95 ± 7.69% and SB202190 = 48.32 ± 6.22%, respectively]. However, as expected, 10 µM U0126 was not effective in blocking (−)-xanthatin’s actions [i.e., (%) inhibition of cell viability, 89.21 ± 8.31%], data that further support the mechanistic involvement of the stress-responsive JNK and p38 MAP kinase-mediated signaling pathways as effectors of (−)-xanthatin’s activities. To further investigate the mode of cell death activated by the 10 µM (−)-xanthatin-treatments, DNA fragmentation patterns were analyzed by gel electrophoresis. The results demonstrated no detectable DNA fragmentation in the (−)-xanthatin-treated cells (Figure 4B, indicated by Xa), whereas actinomycin D (Act D)-treatments, serving as a positive control for apoptosis, produced readily apparent DNA fragmentation patterns (Figure 4B, indicated by Act D). When comparing the control and 10 µM (−)-dihydroxanthatin-treated lanes, (−)-xanthatin treatment for 48 h generated considerably large amounts of high molecular weight (HMW) DNA fragments (>2 kbp) but no short oligonucleo-somes typically characteristic of apoptotic cell death (Figure 4B, indicated by Act D). Further, when 50 µM Z-VAD-FMK, a pan-caspase inhibitor, was added in combination with (−)-xanthatin, no detectable changes resulted in either (−)-xanthatin-induced cell death indices or cellular morphology of the MDA-MB-231 cells (data not shown). In addition, it was demonstrated that (−)-xanthatin markedly evoked the death response of MCF-7 breast cancer cells, with an IC50 value of 5.05 µM (Figure 4C), comparable to the effects noted with MDA-MB-231 cells following treatment with the compound (Figure 1, inset). It should also be noted that (−)-xanthatin was approximately 3-fold more potent than (+)-8-epi-xanthatin in lowering MCF-7 cell viability (IC50 values of 5.05 µM vs 16.13 µM). Since MCF-7 cells are caspase-3-deficient,41 these data strongly suggest that (−)-xanthatin-induced cell death is not mediated through caspase activation of apoptotic pathways.

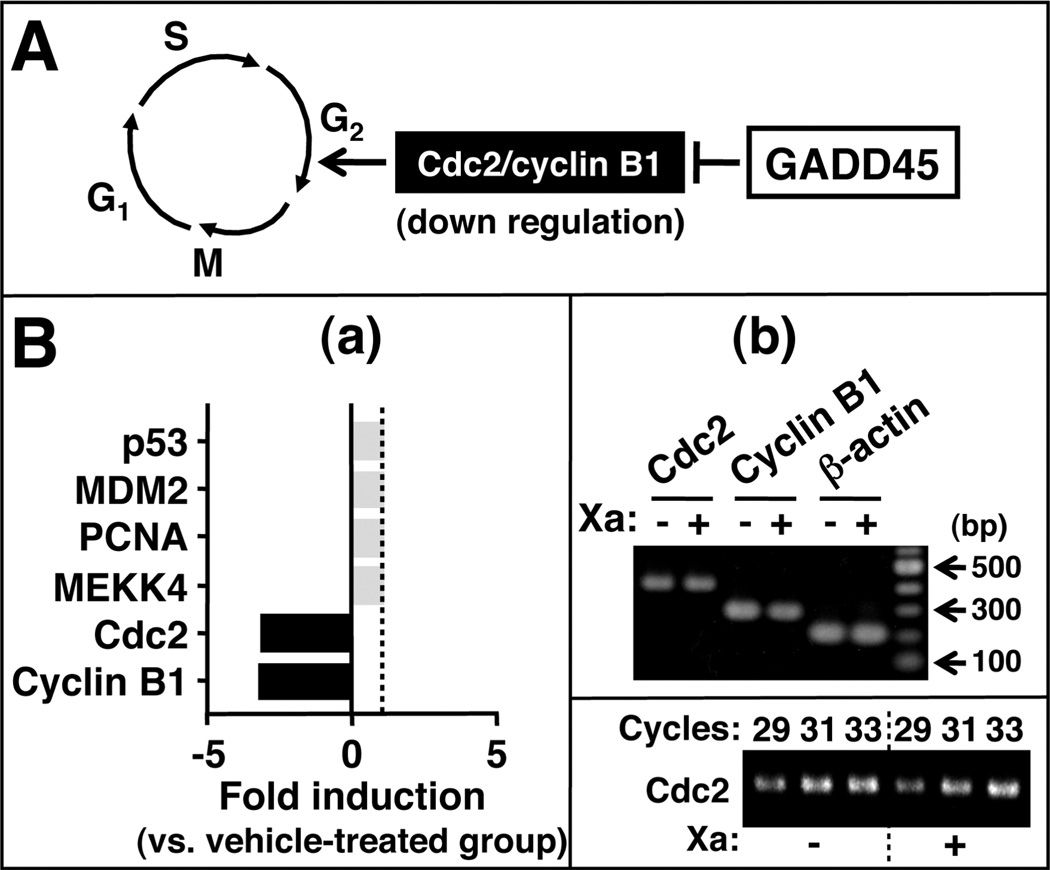

(−)-Xanthatin Represses Genes Involved in the Cell Cycle G2/M Checkpoints

In addition to being rapidly induced by DNA-damaging agents, accumulating evidence suggests that the GADD45 family belongs to a subset of genes that are coordi-nately activated in growth-arrested cells. 17,42 Using DNA micro-array and RT-PCR analyses, we evaluated GADD45 responses in (−)-xanthatin treated MDA-MB-231 cells since all three GADD45 isoforms are suggested to cause cell cycle arrest at the G2/M transition via the inhibition of Cdc2/cyclin B117,43 (Figure 5A). Among the GADD45-interactive molecules in cell cycle regulation, Cdc2 and cyclin B1 were selectively down-regulated (3.0- and 3.3-fold, respectively) by (−)-xanthatin (Figure 5B–a), indicating that this agent’s antiproliferative activities are likely mediated, at least in part, through GADD45-mediated inhibition of Cdc2/cyclin B1 and subsequent reduction of G2/M checkpoint control (Figure 5B–a and -b).

Figure 5.

(−)-Xanthatin suppresses key genes involved in the G2/M checkpoint. (A) GADD45 molecules can inhibit Cdc2/cyclin B1 involved in the G2/M checkpoint. (B-a) Results of DNA microarray analysis were presented. Data are expressed as the fold induction vs vehicle-treated groups. MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with the vehicle or 10 µM (−)-xanthatin for 48 h, followed by mRNA isolation. Details of microarray conditions are described under Materials and Methods. (B-b) RT-PCR analysis of Cdc2 and cyclin B1 mRNA levels after treatment with (+) or without (−) 10 µM (−)-xanthatin. β-Actin was used as an RNA normalization control. Also see the inset (Cdc2). A100-bp DNA ladder marker was also loaded. Xa, (−)-xanthatin. A representative data image is shown.

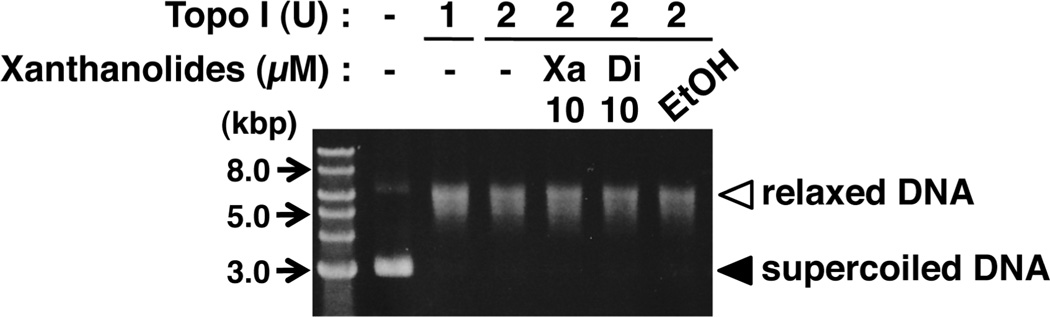

(−)-Xanthatin Does Not Affect Topoisomerase I (Topo I)-Mediated DNA Relaxation

It is well-established that GADD45 genes are induced by stimuli leading to DNA damage.17,19,20 On the basis of these considerations, we asked whether (−)-xanthatin may affect Topo I-catalyzed DNA relaxation, as Topo I plays a major role in regulating genomic DNA topology, modulating supercoiled to relaxed DNA transitions.44 Following the incubation of supercoiled DNA and Topo I, reaction products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. The supercoiled DNA was almost completely converted into relaxed DNA in the presence of 1 or 2 U Topo I (Figure 6). Under these conditions, no inhibitory effect of 10 µM (−)-xanthatin on Topo I was detected (up to 25 µM; data not shown). Similar results were obtained with 10 µM (−)-dihydroxanthatin (Figure 6), suggesting that (−)-xanthatin induces GADD45γ through the induction of cellular stress and not through the inhibition of a Topo I-catalyzed reaction (see also Figure 3C and 3D). These results are in contrast to the anticancer drug, camptothecin, which causes DNA damage by affecting Topo I-catalyzed reactions44 and subsequent induction of GADD45 genes.45

Figure 6.

(−)-Xanthatin does not affect topoisomerase I (Topo I)-mediated DNA relaxation. Effects of (−)-xanthatin and (−)-dihydrox-anthatin on Topo I-catalyzed DNA relaxation are shown. The filled vs unfilled arrowheads refer to the positions of supercoiled DNA and relaxed DNA, respectively. After the incubation of Topo I alone or in combination with xanthanolides, each sample was subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis, followed by staining with ethidium bromide. A 1-kbp DNA ladder marker was also loaded. Xa, (−)-xanthatin; and Di, (−)-dihydroxanthatin. A representative data image is shown.

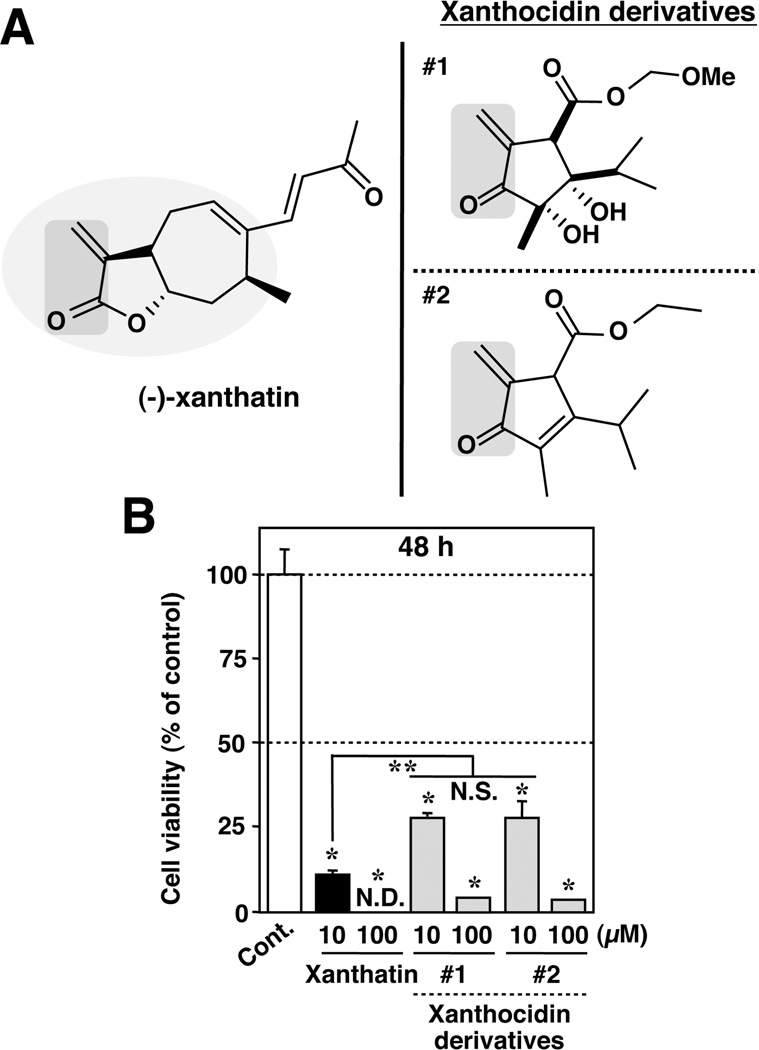

(−)-Xanthatin-Mediated Antiproliferative Effects on MDA-MB-231 Cells Minimally Require Its Exomethylene-Coupled Carbonyl Moiety in the Structure

Our prior data (Figures 1 and 2) suggested that the exo-methylene lactone moiety is a possible active center mediating both (−)-xanthatin’s antiproliferative and cell death effects on MDA-MB-231 cells. To test this concept in some detail, we synthesized two additional xanthocidin derivatives, containing an exo-methylene-coupled carbonyl moiety, in the cyclopentane or cyclopentene ring, respectively (Figure 7A, right panel; structures #1 and #2). As shown in Figure 7A (right panel), #2 contains two potential Michael acceptor centers. One is the exo-methylene-coupled carbonyl moiety, and the other is an enone moiety, as compared with structure #1. When tested experimentally at 10 µM concentrations, the derivatives #1 and #2 exhibited comparatively similar inhibitory effects on the breast cancer line’s viability (Figure 7B), even though derivative #2 contains the additional enone moiety. When compared with (−)-xanthatin’s suppressive effects, both of the xanthocidin derivatives exhibited much weaker growth suppression in the MDA-MB-231 cells. It is possible that the results may be influenced by differences in the compounds’ inherent lipophilicity, although it is notable that both of the xanthocidin derivatives did produce statistically significant inhibitory effects on cell viability at 10 µM. Therefore, these data strongly suggest that the exo-methylene-coupled carbonyl moiety (Figure 7A, left panel; indicated by a gray circle) in the structure of (−)-xathatin is critically important for its inhibitory activity on cell viability, whereas the entire structure of (−)-xanthatin, except for a dienone moiety, contributes importantly to the cancer cell antiproliferative function.

Figure 7.

(−)-Xanthatin-mediated antitumor effects minimally require its exo-methylene-coupled carbonyl moiety. (A) Chemical structures of (−)-xanthatin (left panel) and two xanthocidin derivatives (right panel, #1 and #2). The exo-methylene-coupled carbonyl moiety in the structures is indicated with a gray inclusion. Me, − CH3 (methyl group). (B) MDA-MB-231 cells were exposed for 48 h to the indicated concentrations (10, 100 µM) of the compounds listed in panel A. Data are expressed as the percent of the vehicle-treated group (control) and represent the mean ± SD (n = 5). *Significantly different (p < 0.05) from the control. **Significantly different (p < 0.05) from the 10 µM (−)-xanthatin-treated group. N.D., not detectable (because of complete cell death). N.S., not significant.

DISCUSSION

Among established human breast cancer cell lines, MDA-MB-231 cells are well recognized as a highly aggressive breast cancer model. If breast cancer cells express estrogen receptors (ERs) and their proliferation is estrogen dependent, ER antagonists and aromatase inhibitors are typically chosen as potentially effective treatment regimens.8,13 However, for ER-negative breast tumors, as modeled by the MDA-MB-231 cells in vitro, other strategies are usually more effective, such as the transformation of ER-negative into ER-positive breast cancer cells using ER cDNA transfection or re-expression of the ERgene by demethylating its promoter. 46 However, these modalities are only employed in vitro, severely limiting the gamut of effective alternative strategies in vivo. The study presented here focuses on the investigation and promise of developing new chemical agents exhibiting anticancer potential for aggressive ER-negative breast cancers.

In this regard, various sesquiterpene lactones have been recognized previously as toxic to both humans and animals, with a view that these substances are nonselectively reactive with cellular macromolecules.47 However, among the discovered sesquiterpene lactones, (−)-xanthatin, derived from extracts of X. strumarium (Cocklebur) has been reported as exhibiting little or no toxicity to animals, exhibiting an LD50 value of ∼800 mg/kg.48 However, previous studies on (−)-xanthatin have relied on preparations derived from crude extracts of plant materials. In the current study, we performed chemical syntheses to derive pure preparations of (−)-xanthatin and other xanthanolide sesquiterpene lactone derivatives, and studied these agents as potential anticancer modalities in an MDA-MB-231 cell model. The results demonstrated strikingly that among these chemically related substances, (−)-xanthatin was a highly effective inhibitor of cancer cell proliferation, as well as an inducer of cancer cell death.

Mechanistically, we attempted to define the mode of action of (−)-xanthatin’s antiproliferative effects. Initial results indicated that the mechanism of the (−)-xanthatin-mediated effects on MDA-MB-231 cells was distinct from that of FTase inhibition and/or the associated up-regulation of the p21 gene, an important cell-cycle suppressor (Figure 3A and B). We also evaluated whether (−)-xanthatin may interfere with Topo I-catalyzed DNA relaxation, as Topo I is known to play a major role in regulating DNA topology by modulating its transition from supercoiled DNA into relaxed DNA.44 The anticancer drug, camptothecin, causes DNA damage by modulating the Topo I-catalyzed reaction,45 resulting in cell death accompanied by DNA fragmentation.44 However, at 10 µM (−)-xanthatin, the concentration that effectively compromises MDA-MB-231 cell viability (Figure 2A, right panel), no Topo I inhibition or characteristic DNA fragmentation patterns could be detected (Figures 4B and 6). Rather, (−)-xanthatin treatment resulted in the production of HMW DNA fragments in the absence of oligonucleosomal DNA fragmentation, suggesting a caspase-independent apoptotic mechanism.49 The anticancer agent, irofulven (6-hydroxymethylacylfulvene), is an analogue of illudin S that possesses sesquiterpene and methylene-coupled carbonyl moieties and also appears to evoke a caspase-independent apoptosis with concomitant appearance of HMW DNA fragments in MDA-MB-231 cells.50 We further investigated the effect of the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK on (−)-xanthatin’s activity. However, Z-VAD-FMK additions resulted in no observable morphological change or cell death when combined with (−)-xanthatin treatments, further supporting a caspase-independent mode of cell death. Others have also reported that cellular apoptosis induced by arucanolide, a sesquiterpene lactone, is similarly insensitive to Z-VAD-FMK.51 To obtain more evidence supporting a caspase-independent cell death primed by (−)-xanthatin, we further investigated the effect of (−)-xanthatin on MCF-7 cells, a breast cancer cell line having a caspase-3 deficient background.41 MCF-7 cell proliferation and viability were also remarkably suppressed by (−)-xanthatin (Figure 4C). Therefore, these results support the concept that the potent suppressive effects of (−)-xanthatin on breast cancer lines involve a mode of action involving one or more caspase-independent pathways.

One potential mechanistic pathway accounting for (−)-xanthatin’s antiproliferative effects is that of oxidative stress, as the (−)-xanthatin-induced effects on cell viability were abrogated by pretreatment of the MDA-MB-231 cell cultures with antioxidants such as NAC and Vit.C (Figure 3D). Of note, NAC, a thiol (-SH)-containing compound, was more effective than Vit.C, suggesting that oxidative stress pathways potentially involving interaction between (−)-xanthatin and cysteine residue (s) in protein targets are involved in the (−)-xanthatin’s antiproliferative effects. It was reported previously that chemicals containing a sesquiterpene lactone moiety are effective activators of oxidative stress pathways.1 In this respect, GADD45 genes, including GADD45γ, are recognized as early response genes that are induced following DNA damage produced by stress stimuli.17,19,20 Using DNA microarray and corroborative gene expression analyses, we identified several modulated genes in response to (−)-xanthatin treatment. The GADD45γ gene in particular was remarkably elevated in MDA-MB-231 cells, along with gene expression changes involved in the GADD45-related signaling pathways (both up-and down-regulation). In addition, the HO-1 and IL-1β gene transcripts were identified as up-regulated by (−)-xanthatin-mediated treatments and stress response genes that may in turn lead to the induction of the GADD45 gene responses noted. We also observed up-regulation of other oxidative stress-responsive genes such as HSPA1A/HSP70 and HSPA6/HSP70B′.52 If one of the triggers primed by (−)-xanthatin is oxidative stress, it appears to follow that expression of stress-responsive genes, such as HO-1 and IL-1β, would exhibit up-regulation and that antioxidants would function to effectively block the cell death responses produced by (−)-xanthatin.

Although all three GADD45 isoforms are implicated in cell cycle arrest at the G2/M transition, through inhibition of Cdc2/cyclin B1,17,43 among the GADD45-interactive molecules in cell cycle regulation, we identified that Cdc2 and cyclin B1 were selectively down-regulated (3.0 and 3.3-fold, respectively) by (−)-xanthatin. These results indicate that this agent’s antiproliferative activities are likely mediated, at least in part, through GADD45-mediated inhibition of Cdc2/cyclin B1 and subsequent reduction of G2/M checkpoint control.

Accumulating experimental evidence indicates that GADD45γ, but not GADD45Cα or GADD45β, functions as a tumor suppressor gene in cancers, leading to G2/M arrest, followed by apoptosis.18,52 In addition, the GADD45γ gene is rarely mutated in tumors.18,53 Thus, ectopic expression of GADD45γ is being explored as a novel strategy to inhibit tumor growth. Although GADD45γ appears as an attractive target for cancer treatment, to our knowledge no selective inducer of the GADD45γ isoform has been identified previously. The results presented here suggest the novel possibility that (−)-xanthatin may have therapeutic value as a selective inducer of GADD45γ in human cancer cells, in particular FTI-resistant aggressive breast cancers. Further studies are required to ascertain exact mechanistic targets of (−)-xanthatin’s antiproliferative and cell killing effects in breast cancer models (Figure 8).

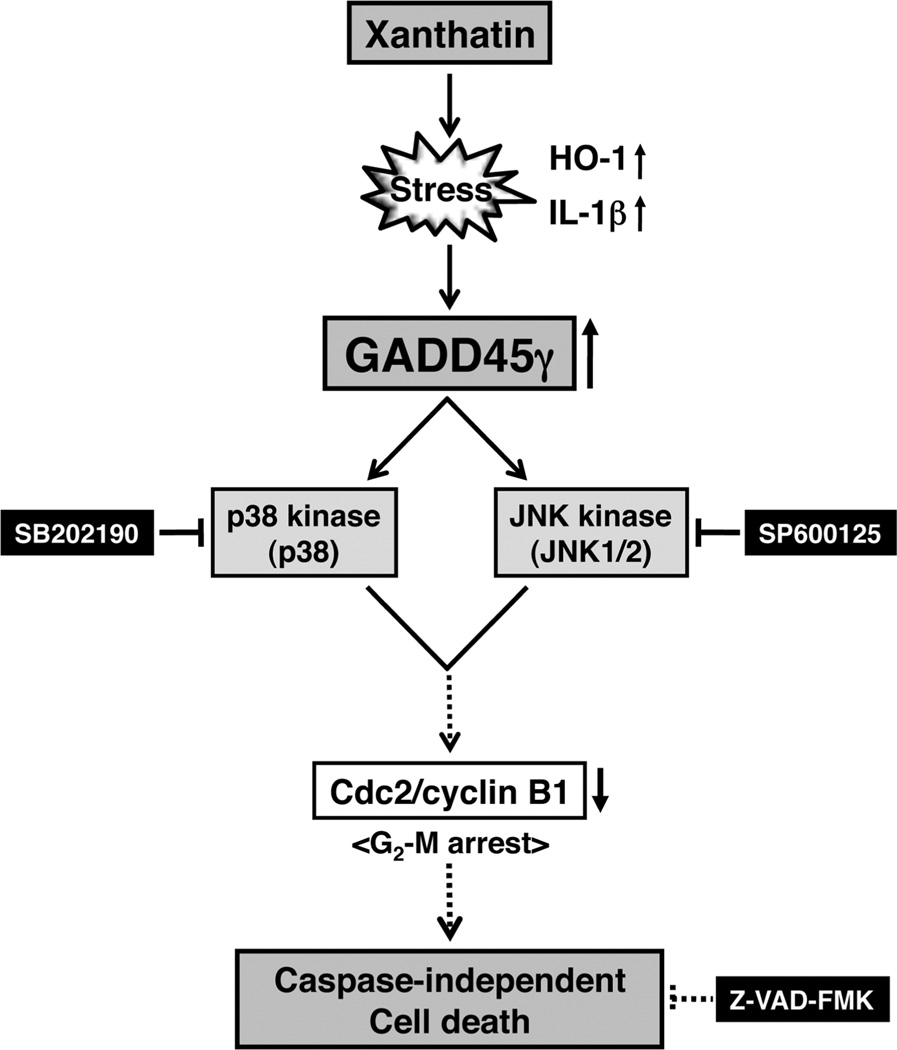

Figure 8.

Summary of the (−)-xanthatin-mediated antiproliferation effects on human breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells. In this study, it was revealed that (−)-xanthatin selectively induced the GADD45γ gene, a tumor suppressor, in MDA-MB-231 breast caner cells. The GADD45γ gene is induced by certain stresses evoked by (−)-xanthatin, followed by the activation of stress-responsive MAPK (JNK and p38)-mediated signaling pathways. These activities are blocked by the specific inhibitors, SP600125 and SB202190, respectively. Conceivably, GADD45γ-mediated G2/M arrest may be caused by the down-regulation of Cdc2/cyclin B1. Finally, damaged cells result in caspase-independent cell death but not in necrosis. Z-VAD-FMK, a pan-caspase inhibitor, does not interfere with (−)-xanthatin-induced cell death. Solid lines indicate interactions of the former and the later that were demonstrated directly by the results of this study; hypothesized interactions are denoted with dotted lines.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

This work was performed under the Cooperative Research Program of Network Joint Research Center for Materials and Devices [Research No. 2011290, (H.A.)]. This study was supported in part by the Program for Promotion of Basic and Applied Researches for Innovations in Bio-oriented Industry [(BRAIN) (M.S.)], and supported by Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) [Research Nos. 20790149 and 22790176, (S.T.)] from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sport, Science and Technology of Japan. This study was also supported by the donation from NEUES Corporation, Japan (H.A.). K.M. and K.Y. also acknowledge the support of the JSPS. C.J.O. was supported by a USPHS award, ES016358.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhang S, Won YK, Ong CN, Shen HM. Anticancer potential of sesquiterpene lactones: bioactivity and molecular mechanisms. Curr. Med. Chem. Anticancer Agents. 2005;5:239–249. doi: 10.2174/1568011053765976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim YS, Kim JS, Park SH, Choi SU, Lee CO, Kim SK, Kim YK, Kim SH, Ryu SY. Two cytotoxic sesquiterpene lactones from the leaves of Xanthium strumarium and their in vitro inhibitory activity on farnesyltransferase. Planta Med. 2003;69:375–377. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-38879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gibbs JB, Oliff A, Kohl NE. Farnesyltransferase inhibitors: Ras research yields a potential cancer therapeutic. Cell. 1994;77:175–178. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90308-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fritz G, Kaina B. Rho GTPases: promising cellular targets for novel anticancer drugs. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets. 2006;6:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jordan VC. Tamoxifen: toxicities and drug resistance during the treatment and prevention of breast cancer. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1995;35:195–211. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.35.040195.001211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santen RJ, Harvey HA. Use of aromatase inhibitors in breast carcinoma. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 1999;6:75–92. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0060075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rochefort H, Glondu M, Sahla ME, Platet N, Garcia M. How to target estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 2003;10:261–266. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0100261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brueggemeier RW, Hackett JC, Diaz-Cruz ES. Aromatase inhibitors in the treatment of breast cancer. Endocr. Rev. 2005;26:331–345. doi: 10.1210/er.2004-0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watanabe K, Motoya E, Matsuzawa N, Funahashi T, Kimura T, Matsunaga T, Arizono L, Yamamoto I. Marijuana extracts possess the effects like the endocrine disrupting chemicals. Toxicology. 2005;206:471–478. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamaguchi Y, Takei H, Suemasu K, Kobayashi Y, Kurosumi M, Harada N, Hayashi S. Tumor-stromal interaction through the estrogen-signaling pathway in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4653–4662. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miki Y, Suzuki T, Tazawa C, Yamaguchi Y, Kitada K, Honma S, Moriya T, Hirakawa H, Evans DB, Hayashi S, Ohuchi N, Sasano H. Aromatase localization in human breast cancer tissues: possible interactions between intratumoral stromal and parenchymal cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3945–3954. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takeda S, Yamaori S, Motoya E, Matsunaga T, Kimura T, Yamamoto I, Watanabe K. Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol enhances MCF-7 cell proliferation via cannabinoid receptor-independent signaling. Toxicology. 2008;245:141–146. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takeda S, Yamamoto I, Watanabe K. Modulation of Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol-induced MCF-7 breast cancer cell growth by cyclooxygenase and aromatase. Toxicology. 2009;259:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2009.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Price JE, Polyzos A, Zhang RD, Daniels LM. Tumorigenicity and metastasis of human breast carcinoma cell lines in nude mice. Cancer Res. 1990;50:717–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Denoyelle C, Albanese P, Uzan G, Hong L, Vannier JP, Soria J, Soria C. Molecular mechanism of the anti-cancer activity of cerivastatin, an inhibitor of HMG-CoA reductase, on aggressive human breast cancer cells. Cell. Signalling. 2003;215:327–338. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(02)00124-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pillé JY, Denoyelle C, Varet J, Bertrand JR, Soria J, Opolon P, Lu H, Pritchard LL, Vannier JP, Malvy C, Soria C, Li H. Anti-RhoA and anti-RhoC siRNAs inhibit the proliferation and invasiveness of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells in vitro and in vivo . Mol. Ther. 2005;11:267–274. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fornace AJ, Jr, Nebert DW, Hollander MC, Luethy JD, Papathanasiou M, Fargnoli J, Holbrook NJ. Mammalian genes coordinately regulated by growth arrest signals and DNA-dama-ging agents. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:4196–4203. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.10.4196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ying J, Srivastava G, Hsieh WS, Gao Z, Murray P, Liao SK, Ambinder R, Tao Q. The stress-responsive gene GADD45G is a functional tumor suppressor, with its response to environmental stresses frequently disrupted epigenetically in multiple tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005;11:6442–66449. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takekawa M, Maeda T, Saito H. Protein phosphatase 2Calpha inhibits the human stress-responsive p38 and JNK MAPK pathways. EMBO. J. 1988;17:4744–4752. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takekawa M, Saito H. Afamily of stress-inducible GADD45-like proteins mediate activation of the stress-responsive MTK1/MEKK4MAPKKK. Cell. 1998;95:521–530. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81619-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schaeffer HJ, Weber MJ. Mitogen-activated protein kinases: specific messages from ubiquitous messengers. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:2435–2444. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.2435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mansouri A, Ridgway LD, Korapati AL, Zhang Q, Tian L, Wang Y, Siddik ZH, Mills GB, Claret FX. Sustained activation of JNK/p38 MAPK pathways in response to cisplatin leads to Fas ligand induction and cell death in ovarian carcinoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:19245–19256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208134200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsuo K, Ohtsuki K, Yoshikawa T, Shishido K, Yokotani-Tomita K, Shindo M. Total synthesis of xanthanolides. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:8407–8419. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsuo K, Yokoe H, Shishido K, Shindo M. Synthesis of diversifolide and structure revision. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:4279–4281. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohtsuki K, Matsuo K, Yoshikawa T, Moriya C, Tomita-Yokotani K, Shishido K, Shindo M. Total synthesis of (+)- and (−)-sundiversifolide via intramolecular acylation and determination of the absolute configuration. Org. Lett. 2008;10:1247–1250. doi: 10.1021/ol8001333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yaji K, Shindo M. Total synthesis of (±)-xanthocidin using FeCl3-mediated Nazarov reaction. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:9808–9813. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steuerwald N, Cohen J, Herrera RJ, Brenner CA. Quantification of mRNA in single oocytes and embryos by realtime rapid cycle fluorescence monitored RT-PCR. Mol Hum. Reprod. 2000;6:448–453. doi: 10.1093/molehr/6.5.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takeda S, Kitajima Y, Ishii Y, Nishimura Y, Mackenzie PI, Oguri K, Yamada H. Inhibition of UDP-glucuronosyl-transferase 2B7-catalyzed morphine glucuronidation by ketoconazole: dual mechanisms involving a novel noncompetitive mode. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2006;34:1277–1282. doi: 10.1124/dmd.106.009738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takeda S, Misawa K, Yamamoto I, Watanabe K. Cannabidiolic acid as a selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitory component in cannabis. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2008;36:1917–1921. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.020909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takeda S, Usami N, Yamamoto I, Watanabe K. Cannabidiol-2′,6′-dimethyl ether, a cannabidiol derivative, is a highly potent and selective 15-lipoxygenase inhibitor. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2009;37:1733–1737. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.026930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takeda S, Jiang R, Aramaki H, Imoto M, Toda A, Eyanagi R, Amamoto T, Yamamoto I, Watanabe K. Δ9 -Tetrahydrocannabinol and its major metabolite Δ9 -tetrahydrocannabinol-11-oic acid as 15-lipoxygenase inhibitors. J. Pharm. Sci. 2011;100:1206–1211. doi: 10.1002/jps.22354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Janzowski C, Glaab V, Mueller C, Straesser U, Kamp HG, Eisenbrand G. α, β-Unsaturated carbonyl compounds: induction of oxidative DNA damage in mammalian cells. Mutagenesis. 2003;18:465–470. doi: 10.1093/mutage/geg018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lerner EC, Qian Y, Blaskovich MA, Fossum RD, Vogt A, Sun J, Cox AD, Der CJ, Hamilton AD, Sebti SM. Ras CAAX peptidomimetic FTI-277 selectively blocks oncogenic Ras signaling by inducing cytoplasmic accumulation of inactive Ras-Raf complexes. J. Biol Chem. 1995;270:26802–26806. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.26802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Delarue FL, Adnane J, Joshi B, Blaskovich MA, Wang DA, Hawker J, Bizouarn F, Ohkanda J, Zhu K, Hamilton AD, Chellappan S, Sebti SM. Farnesyltransferase and ger-anylgeranyltransferase I inhibitors upregulate RhoB expression by HDAC1 dissociation, HAT association and histone acetylation of the RhoB promoter. Oncogene. 2007;26:633–640. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crowell PL, Lin S, Vedejs E, Gould MN. Identification of metabolites of the antitumor agent d-limonene capable of inhibiting protein isoprenylation and cell growth. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 1992;31:205–212. doi: 10.1007/BF00685549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hardcastle IR, Rowlands MG, Barber AM, Grimshaw RM, Mohan MK, Nutley BP, Jarman M. Inhibition of protein prenylation by metabolites of limonene. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999;57:801–809. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(98)00349-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sepp-Lorenzino L, Rosen N. A farnesyl-protein transferase inhibitor induces p21 expression and G1 block in p53 wild type tumor cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:20243–20251. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Du W, Lebowitz PF, Prendergast GC. Cell growth inhibition by farnesyltransferase inhibitors is mediated by gain of geranylgeranylated RhoB. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:1831–1840. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oguro T, Hayashi M, Numazawa S, Asakawa K, Yoshida T. Heme oxygenase-1 gene expression by a glutathione depletor, phorone, mediated through AP-1 activation in rats. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996;221:259–265. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arrigo AP. Gene expression and thiol redox state. Free Radical Biol. Med. 1999;27:936–944. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00175-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li F, Srinivasan A, Wang Y, Armstrong RC, Tomaselli KJ, Fritz LC. Cell-specific induction of apoptosis by microinjection of cytochrome c. Bcl-xL has activity independent of cytochrome c release. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:30299–30305. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.48.30299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rishi AK, Sun RJ, Gao Y, Hsu CK, Gerald TM, Sheikh MS, Dawson MI, Reichert U, Shroot B, Fornace AJ, Jr, Brewer G, Fontana JA. Post-transcriptional regulation of the DNA damage-inducible gadd45 gene in human breast carcinoma cells exposed to a novel retinoid CD437. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:3111–3119. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.15.3111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vairapandi M, Balliet AG, Hoffman B, Liebermann DA. GADD45β and GADD45γ are cdc2/cyclinB1 kinase inhibitors with a role in S and G2/M cell cycle checkpoints induced by genotoxic stress. J. Cell. Physiol. 2002;192:327–338. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsao YP, Russo A, Nyamuswa G, Silber R, Liu LF. Interaction between replication forks and topoisomerase I-DNA cleavable complexes: studies in a cell-free SV40 DNA replication system. Cancer Res. 1993;53:5908–5914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xiao G, Chicas A, Olivier M, Taya Y, Tyagi S, Kramer FR, Bargonetti J. A DNA damage signal is required for p53 to activate gadd45. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1711–1719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang X, Phillips DL, Ferguson AT, Nelson WG, Herman JG, Davidson NE. Synergistic activation of functional estrogen receptor (ER)-α by DNA methyltransferase and histone deacetylase inhibition in human ER-alpha-negative breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7025–7029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Piovano M, Chamy MC, Garbarino JA, Quilhot W. Secondary metabolites in the genus Sticta (lichens) Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2000;28:589–590. doi: 10.1016/s0305-1978(99)00092-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roussakis C, Chinou I, Vayas C, Harvala C, Verbist JF. Cytotoxic activity of xanthatin and the crude extracts of Xanthium strumarium . Planta Med. 1994;60:473–474. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-959537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Solovyan VT, Bezvenyuk ZA, Salminen A, Austin CA, Courtney MJ. The role of topoisomerase II in the excision of DNA loop domains during apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:21458–21467. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110621200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Herzig MC, Liang H, Johnson AE, Woynarowska B, Woynarowski JM. Irofulven induces apoptosis in breast cancer cells regardless of caspase-3 status. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2002;71:133–143. doi: 10.1023/a:1013855615712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nakagawa Y, Iinuma M, Matsuura N, Yi K, Naoi M, Nakayama T, Nozawa Y, Akao Y. A potent apoptosis-inducing activity of a sesquiterpene lactone, arucanolide, in HL60 cells: a crucial role of apoptosis-inducing factor. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2005;97:242–252. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fp0040456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gomer CJ, Ryter SW, Ferrario A, Rucker N, Wong S, Fisher AM. Photodynamic therapy-mediated oxidative stress can induce expression of heat shock proteins. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2355–2360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zerbini LF, Libermann TA. GADD45 deregulation in cancer: frequently methylated tumor suppressors and potential therapeutic targets. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005;11:6409–6413. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]