Abstract

In the past decade, several experimental studies demonstrated an inhibitory effect of calcimimetics on the progression of vascular calcification in animals with chronic kidney disease (CKD), in keeping with the expression of the calcium-sensing receptor (CaR) in vascular tissue. In addition, calcimimetics were also found to prevent the arterial remodeling caused by CKD and to slow the progression of atherosclerosis in uremic rats and mice, respectively. The mode of action of these CaR modulators could be both via a better control of secondary hyperparathyroidism and direct effects on the vessel wall. Two main clinical trials, ADVANCE and EVOLVE, recently evaluated in patients with CKD stage 5D the effects of the calcimimetic cinacalcet on the progression of vascular calcification and hard cardiovascular outcomes, respectively. Both trials missed their respective primary end point by intent-to-treat analysis although by other prespecified analyses, including adjustment for baseline characteristics, there was strong suggestive evidence in favor of reductions in risk, in agreement with numerous experimental studies. Further clinical trials are needed to settle this issue definitively.

Keywords: calcimimetics, CKD, CKD-MBD, vascular calcification, outcomes

The development of calcimimetics, which are synthetic allosteric modulators of the calcium-sensing receptor (CaR), has been a breakthrough in the treatment of secondary hyperparathyroidism in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Calcimimetics are also in clinical use for patients with primary hyperparathyroidism and those with parathyroid carcinoma. Several different compounds have been synthesized, but the only calcimimetic presently available for treatment in human patients is cinacalcet.

Initially, it was thought that the CaR was mainly expressed in organs regulating systemic calcium homeostasis, including kidney, intestine, bone, thyroid, and the parathyroid glands. Subsequently, it became clear that this receptor, which is the first identified G protein–coupled receptor to be activated by an ion,1 is present in many other tissues and cell types, including the cardiovascular system,2, 3, 4, 5 and exerts many functions other than the regulation of serum Ca2+.1

In the setting of CKD, the cellular expression of the CaR has been shown to be reduced as compared with physiological conditions. Initially, CaR downregulation was shown in parathyroid tissue.6, 7, 8, 9, 10 This process apparently occurs not before but only after the development of parathyroid hyperplasia, as shown in rats with short-term CKD.9 It is enhanced by high phosphate intake.10 It can be upregulated by the administration of calcimimetics, concomitantly with the correction of reduced vitamin D receptor expression.11 Notably, CaR activation by calcimimetics has also been reported to accelerate parathyroid apoptosis in uremic rats.12

Subsequently, it was found that CaR downregulation in CKD also occurred in other tissues, including the cardiovascular system.5 These observations have led to the hypothesis that CaR activation by calcimimetics might exert beneficial effects not only with respect to the CKD-associated bone and mineral disorder (CKD-MBD) but also on CKD-associated cardiovascular disease. Here below we present experimental and clinical evidence in favor of this hypothesis, with main focus on vascular calcification as an intermediate outcome both in experimental and clinical studies and on cardiovascular events and mortality in one animal study and several clinical studies.

EXPERIMENTAL EVIDENCE

As downregulation of CaR expression has been observed in association with calcification of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) in vitro4 and in human atherosclerotic-calcified arteries,4 several groups of authors have assessed the effect of calcimimetics on the progression of vascular calcification in VSMC in vitro and in animal models with CKD in vivo.

In vitro studies

The calcimimetics R-56813 and calindol14 have been shown to decrease VSMC calcification induced by high phosphate concentrations in culture medium. This decrease was abolished in CaR-siRNA-transfected cells.13 The mechanism behind the inhibitory effect of calcimimetics on vascular calcification could be a stimulation of matrix-gla protein (MGP) production by VSMC, as initially suggested by Farzaneh-Far et al.15 and subsequently supported by observations of others in rat and bovine VSMCs, respectively.14, 16 However, in vitro activation of CaR by R-568 did not modify phosphate-enhanced MGP release in our experimental human VSMC model.13 These apparent discrepancies may be due to the use of VSMC from different species, with possibly variable induction of bone morphogenic protein-2 (BMP-2) which is itself a regulator of MGP synthesis and may decrease MGP expression.17 Of interest, in the study by Ciceri et al.14 using bovine VSMC, increased expression of BMP-2 under high medium phosphate conditions was effectively prevented by calindol. Another possibility of the apparently inconsistent findings is that in none of these in vitro studies the state of gamma-glutamyl carboxylation and phosphorylation of the MGP molecule was assessed. Undercarboxylated and nonphosphorylated MGP, but not fully carboxylated and phosphorylated MGP, was found to correlate with vascular calcification in the clinical setting of patients with CKD.18, 19

In vivo studies

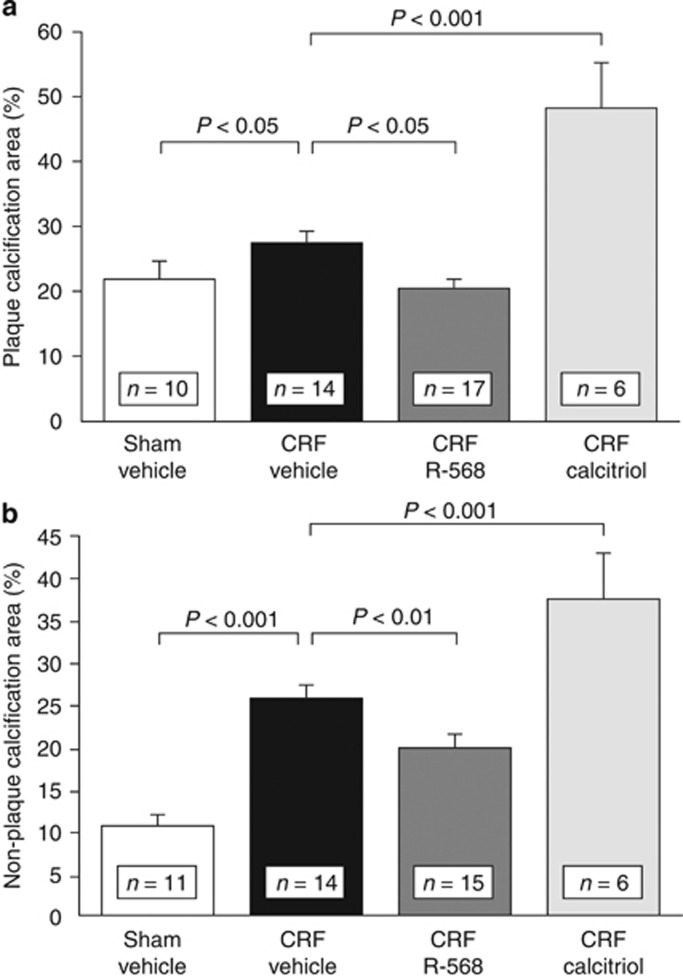

Studies in different animal models of CKD showed an inhibitory effect of the calcimimetics AMG 64120, 21 or cinacalcet22 on the progression of vascular calcification in rats and of the calcimimetic R-568 in mice,13 respectively. Whereas in uremic rats vascular calcification was induced either by pharmacological doses of calcitriol or paricalcitol or by feeding high doses of adenine, in our apolipoprotein E (apoE)-deficient mouse model with superimposed uremia aortic calcification occurred spontaneously, both in media and in atherosclerotic intima (Figure 1). One of the possible mechanisms of action clearly is suppression of parathyroid overfunction, together with a decrease in serum calcium and phosphate concentrations. This is in line with the observation that surgical parathyroidectomy led to a similar reduction in vascular calcification in an experimental model of high-dose calcitriol-induced arterial mineralization.22 The parathyroid hormone (PTH)-dependent effect does, however, not preclude other mechanisms, including the abovementioned direct effects on the vessel wall. In recent clinical studies, the administration of cinacalcet led to a decrease in circulating fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) concentration, whereas vitamin D and/or its active derivatives generally increased it.23, 24, 25 However, such an effect of calcimimetics on serum FGF23 was not observed in two recent animal studies.13, 26 Whether FGF23 favors the occurrence or progression of vascular calcification27, 28 or not29, 30 remains an unsolved issue, in contrast to the well-established negative effects of high FGF23 on cardiac structure and function.31

Figure 1.

Aortic calcification in chronic renal failure (CRF) and non-CRF apoE−/− mice treated with vehicle, calcimimetic R-568, or high-dose calcitriol; (a) plaque and (b) non-plaque (media) calcification. Both types of calcification were increased in CRF compared with non-CRF apoE−/− mice. CRF apoE−/− mice treated with R-568 exhibited a decrease of aortic root plaque and non-plaque calcification compared with vehicle-treated CRF mice. However, CRF apoE−/− mice treated with a pharmacological dose of calcitriol showed a striking increase of aortic root plaque calcification and nonplaque calcification compared with control CRF mice receiving vehicle. In addition, vascular plaque and non-plaque calcification was higher in calcitriol-treated CRF mice compared with R-568-treated mice (from Ivanovski et al.,13 with permission).

Notably, the administration of calcimimetics also exerted favorable actions on uremia-induced arterial remodeling in rats with CKD,22, 32 together with a decrease in the vascular expression of BMP-2 and a reduction in osteoblastic transdifferentiation of VSMC,32 and reduced the progression of atherosclerosis in apoE-deficient mice with CKD (Figure 2).13

Figure 2.

Aortic root and thoracic aorta plaque area in chronic renal failure (CRF) and non-CRF apoE−/− mice treated with vehicle, calcimimetic R-568, or high-dose calcitriol. (a) Aortic root atherosclerosis lesions were increased in CRF compared with non-CRF apoE−/− mice. R-568-treated CRF mice had a significant decrease in aortic plaque area compared with vehicle-treated CRF apoE−/− mice. No significant change in aortic plaque area was observed in calcitriol-treated CRF apoE−/− mice compared with vehicle-treated CRF apoE−/− mice. (b) Atherosclerotic lesions in thoracic aorta were significantly increased in CRF compared with non-CRF apoE−/− mice. Atherosclerotic lesions were significantly less extended in R-568-treated CRF apoE−/− mice than in vehicle-treated CRF apoE−/− mice. In contrast, high-dose calcitriol-treated CRF apoE−/− mice exhibited a significant increase in lesions at this anatomical site compared with R-568-treated CRF apoE−/− mice, but not compared with vehicle-treated CRF apoE−/− mice (from Ivanovski et al.,13 with permission). NS, not significant.

Most interestingly, Lopez et al.20 were able to demonstrate in their rat model with CKD and arterial calcification induced by high-dose calcitriol treatment that survival was significantly reduced in the animals treated with this most active vitamin D derivative, whereas survival was improved in the animals concomitantly treated with the calcimimetic AMG 641.

Recently, a novel peptide, AMG 416 (formerly KAI-4169 and now named velcalcetide in the United States), has been identified that acts as a CaR agonist.33 It is structurally unrelated to the calcimimetics discussed so far. It acts by a mechanism distinct from that of cinacalcet, the only approved calcimimetic in clinical practice, as it can activate CaR both in the presence and the absence of physiological levels of extracellular Ca2+. This new CaR agonist has also been shown to reduce the progression of vascular calcification in uremic rats (surgical 5/6 nephrectomy model), in addition to a potent inhibitory effect on PTH secretion.33

CLINICAL EVIDENCE

Observational studies

Block et al.34 tested the question whether prescription of the calcimimetic cinacalcet to hemodialysis patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism improved their survival. They prospectively collected data on chronic hemodialysis patients from a large provider in the United States beginning in 2004, a time coincident with the commercial availability of cinacalcet hydrochloride. They merged this information with data in the US Renal Data System to determine all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. All patients included in the study received intravenous treatment with active vitamin D derivatives, which was considered as a surrogate for the diagnosis of parathyroid overfunction. Of the 19,186 patients, 5976 received cinacalcet and all were followed for up to 26 months. They used unadjusted and adjusted time-dependent Cox proportional hazards modeling to analyze the data. They found that all-cause and cardiovascular mortality rates were significantly lower for the hemodialysis patients treated with cinacalcet than for those who did not receive calcimimetic treatment. Thus this observational study found a significant survival benefit associated with cinacalcet prescription in patients receiving intravenous vitamin D. However, the study had several limitations, the most important one being the possibility that residual confounding by indication might be responsible for the findings. Clearly, observational studies such as this one cannot establish a cause-and-effect relationship; they are only hypothesis generating.

Prospective clinical trials

The first large-scale trial of cinacalcet therapy was reported in 2004 in 741 adults with CKD stage 5D. It assessed treatment efficacy based on intact PTH concentrations.35 Between 2004 and early 2012, 11 additional trials were reported, although none was primarily designed to evaluate treatment effects on patient-relevant outcomes, including mortality or adverse events.36

In 2011, Raggi et al.37 reported the results of the ADVANCE study whose objective was to examine whether in chronic hemodialysis patients the administration of cinacalcet plus low-dose vitamin D sterols was superior to flexible doses of vitamin D sterols alone in slowing the progression of vascular and valvular calcification. Eligible subjects were on hemodialysis for 3 months with serum PTH values >300 pg/ml or serum PTH values of 150–300 pg/ml together with a calcium–phosphorus product >50 mg2/dl2 while receiving vitamin D. All subjects received calcium-based phosphate binders. Coronary artery calcification (CAC) and aorta and cardiac valve calcium scores were determined both by Agatston scoring and the more recently developed volume scoring using multi-detector computed tomography. Subjects with Agatston CAC scores ⩾30 were randomized to cinacalcet (30–180 mg/day) plus low-dose calcitriol or vitamin D analog (⩽2 μg paricalcitol equivalent/dialysis) or flexible vitamin D therapy. The primary end point was percentage change in Agatston CAC score from baseline to week 52.

Median Agatston CAC scores increased 24% in the cinacalcet group and 31% in the flexible vitamin D group (P=0.073). Corresponding changes in volume CAC scores were 22 and 30% (P=0.009). Increases in calcification scores were consistently less in the aorta, aortic valve, and mitral valve among subjects treated with cinacalcet plus low-dose vitamin D sterols, and the differences between groups were significant at the aortic valve. The authors concluded that in hemodialysis patients with moderate-to-severe secondary hyperparathyroidism, cinacalcet plus low-dose vitamin D sterols may attenuate vascular and cardiac valve calcification.

In late 2012, Chertow et al.37 reported the Evaluation of Cinacalcet Therapy to Lower Cardiovascular Events (EVOLVE) trial in 3883 patients receiving long-term hemodialysis treatment. It was the first trial specifically designed to evaluate cinacalcet treatment plus standard of care versus placebo plus standard of care on patient-centered outcomes, using a primary composite outcome of all-cause mortality or first nonfatal cardiovascular event (myocardial infarction, myocardial ischemia, heart failure, or peripheral vascular event). Standard of care included the use of phosphate binders and vitamin D sterols. Secondary end points were cardiovascular mortality, stroke, clinical bone fracture, parathyroidectomy, and components of composite primary end point. The trial was event driven, requiring 1882 primary end point events for study termination. Its duration had to be extended by 16 months beyond the initially planned 4 years because of lower event rates than anticipated. The primary analysis was performed on the basis of the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle. Prespecified secondary analyses included multivariable analyses adjusting for baseline characteristics, and companion analyses with lag censoring, in which data were censored 6 months after patients stopped using a study drug. The median duration of study drug exposure was 21.2 months in the cinacalcet group versus 17.5 months in the placebo group. There was a high number of study drug discontinuation by non-protocol-specified reasons in the placebo group, much higher than anticipated, with 20% of patients in that group receiving commercial cinacalcet before the occurrence of a primary event. This high drop-in rate and other factors limited the statistical power of the trial such that, in contrast to the original assumption of a 20% treatment effect, with the observed study duration and observed rates of events, drop-outs, and drop-ins the re-estimated statistical power was only 54%.

The primary composite end point in the EVOLVE trial was reached in 938 of 1948 patients (48.2%) in the cinacalcet group and in 952 of 1935 patients (49.2%) in the placebo group, stratified according to country and diabetes status (relative hazard in the cinacalcet group vs. the placebo group, 0.93; 95% confidence interval, 0.85–1.02, P=0.11). Thus there was a 7% nonsignificant reduction in the risk of the primary composite end point with cinacalcet in the ITT analysis. After adjustment for baseline characteristics, there was a nominally significant 12% reduction in risk. Although analyses accounting for study drug exposure are subject to chance, bias, and confounding, there were consistent (and nominally significant) effects, up to a 15% reduction in the primary composite end point and a 17% reduction in mortality, using the abovementioned prespecified secondary analyses.

Cinacalcet reduced the rate of parathyroidectomy by more than half. As to side effects, hypocalcemia and gastrointestinal adverse events were significantly more frequent in patients receiving cinacalcet, as already reported in the first large cinacalcet trial in 2004.35

Thus EVOLVE did not meet its primary end point in the unadjusted ITT analysis, although it showed a 7% reduction in the risk of death or cardiovascular events with cinacalcet in hemodialysis patients treated for secondary hyperparathyroidism. ITT analyses adjusted for baseline characteristics suggest that treating secondary hyperparathyroidism with cinacalcet results in nominally significant reductions in the risk of death or cardiovascular events. An analysis censoring data after study drug discontinuation suggests a reduced risk with cinacalcet.

CONCLUSION

Numerous experimental studies done in vitro and in vivo have shown that calcimimetics are able to inhibit the mineralization of VSMC and the progression of vascular calcification, respectively. Other beneficial actions on the vessel wall have also been observed. However, in the clinical arena the superiority of calcimimetics over standard of care concerning the progression of vascular calcification and hard cardiovascular outcomes in patients with CKD stage 5D, although probable, has not yet been proven definitively. The limited statistical power of both the ADVANCE trial and the EVOLVE trial done in patients who are frequently frail and chronically ill is certainly the main reason for the persisting uncertainty.

Acknowledgments

This supplement was supported by a grant from the 58th Annual Meeting of the Japanese Society for Dialysis Therapy.

TBD declares having received honoraria as an advisor/consultant to Abbott-AbbVie, Amgen, Baxter, Chugai, F. Hoffman-La Roche, FMC, and Sanofi-Genzyme and having served as a speaker for Abbott-AbbVie, Amgen, Chugai, Kirin, Sanofi-Genzyme, and Vifor.

References

- Riccardi D, Kemp PJ. The calcium-sensing receptor beyond extracellular calcium homeostasis: conception, development, adult physiology, and disease. Annu Rev Physiol. 2012;74:271–297. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-020911-153318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smajilovic S, Hansen JL, Christoffersen TE, et al. Extracellular calcium sensing in rat aortic vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;348:1215–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.07.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegelstein RC, Xiong Y, He C, et al. Expression of a functional extracellular calcium-sensing receptor in human aortic endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;342:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.01.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam MU, Kirton JP, Wilkinson FL, et al. Calcification is associated with loss of functional calcium-sensing receptor in vascular smooth muscle cells. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;81:260–268. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molostvov G, James S, Fletcher S, et al. Extracellular calcium-sensing receptor is functionally expressed in human artery. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293:F946–F955. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00474.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kifor O, Moore FD, Jr, Wang P, et al. Reduced immunostaining for the extracellular Ca2+-sensing receptor in primary and uremic secondary hyperparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:1598–1606. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.4.8636374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogusev J, Duchambon P, Hory B, et al. Depressed expression of calcium receptor in parathyroid gland tissue of patients with hyperparathyroidism. Kidney Int. 1997;51:328–336. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizobuchi M, Hatamura I, Ogata H, et al. Calcimimetic compound upregulates decreased calcium-sensing receptor expression level in parathyroid glands of rats with chronic renal insufficiency. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:2579–2587. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000141016.20133.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter CS, Finch JL, Slatopolsky EA, et al. Parathyroid hyperplasia in uremic rats precedes down-regulation of the calcium receptor. Kidney Int. 2001;60:1737–1744. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin E, Garfia B, Recio FL, et al. Persistent downregulation of calcium-sensing receptor mRNA in rat parathyroids when severe secondary hyperparathyroidism is reversed by an isogenic kidney transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:2110–2116. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000024439.38838.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza FJ, Lopez I, Canalejo R, et al. Direct upregulation of parathyroid calcium-sensing receptor and vitamin D receptor by calcimimetics in uremic rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;296:F605–F613. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90272.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizobuchi M, Ogata H, Hatamura I, et al. Activation of calcium-sensing receptor accelerates apoptosis in hyperplastic parathyroid cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;362:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.07.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanovski O, Nikolov IG, Joki N, et al. The calcimimetic R-568 retards uremia-enhanced vascular calcification and atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E deficient (apoE−/−) mice. Atherosclerosis. 2009;205:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciceri P, Elli F, Brenna I, et al. The calcimimetic calindol prevents high phosphate-induced vascular calcification by upregulating matrix GLA protein. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2012;122:75–82. doi: 10.1159/000349935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farzaneh-Far A, Proudfoot D, Weissberg PL, et al. Matrix gla protein is regulated by a mechanism functionally related to the calcium-sensing receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;277:736–740. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza FJ, Martinez-Moreno J, Almaden Y, et al. Effect of calcium and the calcimimetic AMG 641 on matrix-Gla protein in vascular smooth muscle cells. Calcif Tissue Int. 2011;88:169–178. doi: 10.1007/s00223-010-9442-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebboudj AF, Shin V, Bostrom K. Matrix GLA protein and BMP-2 regulate osteoinduction in calcifying vascular cells. J Cell Biochem. 2003;90:756–765. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlieper G, Westenfeld R, Kruger T, et al. Circulating nonphosphorylated carboxylated matrix gla protein predicts survival in ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:387–395. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010040339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schurgers LJ, Barreto DV, Barreto FC, et al. The circulating inactive form of matrix gla protein is a surrogate marker for vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease: a preliminary report. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:568–575. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07081009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez I, Mendoza FJ, Aguilera-Tejero E, et al. The effect of calcitriol, paricalcitol, and a calcimimetic on extraosseous calcifications in uremic rats. Kidney Int. 2008;73:300–307. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henley C, Davis J, Miller G, et al. The calcimimetic AMG 641 abrogates parathyroid hyperplasia, bone and vascular calcification abnormalities in uremic rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;616:306–313. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung S, Querfeld U, Muller D, et al. Submaximal suppression of parathyroid hormone ameliorates calcitriol-induced aortic calcification and remodeling and myocardial fibrosis in uremic rats. J Hypertens. 2012;30:2182–2191. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328357c049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Kim H, Shin N, et al. Cinacalcet lowering of serum fibroblast growth factor-23 concentration may be independent from serum Ca, P, PTH and dose of active vitamin D in peritoneal dialysis patients: a randomized controlled study. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:112. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-14-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koizumi M, Komaba H, Nakanishi S, et al. Cinacalcet treatment and serum FGF23 levels in haemodialysis patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:784–790. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetmore JB, Liu S, Krebill R, et al. Effects of cinacalcet and concurrent low-dose vitamin D on FGF23 levels in ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:110–116. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03630509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch JL, Tokumoto M, Nakamura H, et al. Effect of paricalcitol and cinacalcet on serum phosphate, FGF-23, and bone in rats with chronic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;298:F1315–F1322. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00552.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desjardins L, Liabeuf S, Renard C, et al. FGF23 is independently associated with vascular calcification but not bone mineral density in patients at various CKD stages. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23:2017–2025. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1838-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoppet M, Hofbauer LC, Brinskelle-Schmal N, et al. Serum level of the phosphaturic factor FGF23 is associated with abdominal aortic calcification in men: the STRAMBO study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E575–E583. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg K, Olauson H, Amin R, et al. Arterial klotho expression and FGF23 effects on vascular calcification and function. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60658. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scialla JJ, Lau WL, Reilly MP, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 is not associated with and does not induce arterial calcification. Kidney Int. 2013;83:1159–1168. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul C, Amaral AP, Oskouei B, et al. FGF23 induces left ventricular hypertrophy. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4393–4408. doi: 10.1172/JCI46122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koleganova N, Piecha G, Ritz E, et al. A calcimimetic (R-568), but not calcitriol, prevents vascular remodeling in uremia. Kidney Int. 2009;75:60–71. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter S, Baruch A, Dong J, et al. Pharmacology of AMG 416 (velcalcetide), a novel peptide agonist of the calcium-sensing receptor, for the treatment of secondary hyperparathyroidism in hemodialysis patients. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013;346:229–240. doi: 10.1124/jpet.113.204834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block GA, Zaun D, Smits G, et al. Cinacalcet hydrochloride treatment significantly improves all-cause and cardiovascular survival in a large cohort of hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2010;78:578–589. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block GA, Martin KJ, de Francisco AL, et al. Cinacalcet for secondary hyperparathyroidism in patients receiving hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1516–1525. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer SC, Nistor I, Craig JC, et al. Cinacalcet in patients with chronic kidney disease: a cumulative meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001436. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raggi P, Chertow GM, Torres PU, et al. The ADVANCE study: a randomized study to evaluate the effects of cinacalcet plus low-dose vitamin D on vascular calcification in patients on hemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:1327–1339. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chertow GM, Block GA, Correa-Rotter R, et al. Effect of cinacalcet on cardiovascular disease in patients undergoing dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2482–2494. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]