Abstract

Although possessing different anthropological origins, there are similarities in the epidemiology of end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) among the indigenous peoples of Australia (the Australian Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders) and New Zealand (Maori and Pacific Peoples). In both countries there is a substantially increased rate of ESKD among these groups. This is more marked in Australia than in New Zealand, but in both countries the relative rate (in comparison to non-indigenous rates) as well as absolute rate have nearly stabilized in recent years. The excess risk affects females particularly—in contrast to the non-indigenous picture. Among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia, there is a strong age interaction, with the most marked risk being among those aged 25 to 45 years. Indigenous peoples are less likely to be treated with home dialysis, and much less likely to receive a kidney transplant. In particular, rates of living donation are very low among indigenous groups in both countries. Outcomes during dialysis treatment and during transplantation are inferior to those of nonindigenous ones, even after adjustment for the higher prevalence of comorbidities. The underlying causes for these differences are complex, but the slowing and possible stabilization of incident rate changes is heartening.

Keywords: Aboriginal dialysis transplant outcomes, Australia, Maori, New Zealand

INTRODUCTION

The indigenous peoples of Australia and New Zealand have different ethnic origins, but many similarities in the trends in end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) in recent times. Within Australia, there are Aboriginal Australians (population approximately 500,000 out of a total of 22 million people) and Torres Strait Islanders (population approximately 35,000). Aboriginal Australians are believed to have crossed from South East Asia (when there was a ‘land-bridge') around 50,000 years ago. Torres Strait Islanders are of Melanesian origin. These groups are usually combined for analyses of indigenous Australians as ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders' (ATSI).

In New Zealand, the Maori are considered as the indigenous people. Anthropologically, they are believed to have migrated from Polynesia in the tenth century. The second group regarded as an ethnic minority (and sharing many of the socio-economic disadvantages) are the Pacific Peoples, composed of recent immigrants from nearby Pacific Islands (Samoa, Cook Islands, Tonga, Niue, Fiji, Tokelau). In the 2006 Census, Maori numbered 565,329 and Pacific Peoples 265,974 of a total NZ resident population of 4,027,947.1 (The 2011 NZ Census was deferred due to the Christchurch earthquake.)

Although there are clear anthropological, geographic, and cultural differences between the various indigenous groups, there are a number of common elements. In both countries, these groups endure high rates of a variety of chronic diseases, especially diabetes and its complications. Their experiences of ESKD and renal replacement therapy (RRT) are remarkably similar.

INCIDENCE OF ESKD AMONG INDIGENOUS PEOPLES IN AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND

The ANZDATA Registry collects data on all people throughout Australia and New Zealand who receive chronic dialysis or a kidney transplant, and is the source of the data in this paper. ‘ESKD incidence' is thus actually the incidence of those who start RRT unless stated otherwise.2

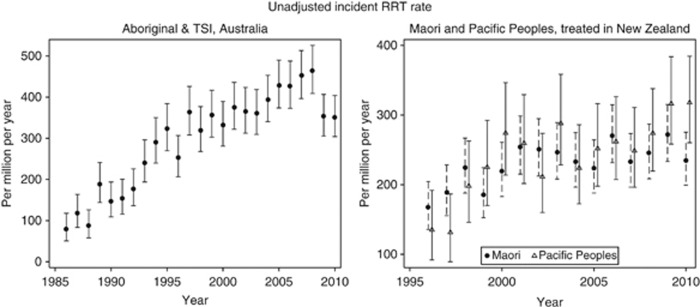

The incidence rates of RRT in the indigenous groups in Australia and New Zealand differ in absolute terms, with current incident rates for ATSI approximately 400 per million per year; rates for Maori and Pacific Peoples in New Zealand are lower (around 250 per million per year). Historically, there was a steady increase in indigenous incidence rates prior to 2000.3 Importantly, however, in the period since 2000 the incidence rates are slowing or have stabilized in both countries (Figure 1). Whether this reflects a stabilization of availability and propensity to treat (following an expansion of renal services) or a stabilization in rates of underlying chronic kidney disease (CKD) is not clear. A recent study demonstrated that (in the period 2003–2007) there was no difference in the proportion of people with ESKD treated with RRT between ATSI and non-indigenous people in Australia.4

Figure 1.

Incident renal replacement therapy rates for indigenous people in Australia and New Zealand. Graphs indicate rate and 95% confidence interval.

Within the overall rates, there is substantial variation in association with a number of factors. The excess rates of RRT are not constant with age or gender, but are greatest in the ‘middle' ages. For ATSI, the overall relative incidence rate in the period 2007–2009 (compared with non-indigenous) was 4.12 (3.82–4.46). However, there were interactions: with gender—among females the RR was 5.98 (5.37–6.66) and male 3.01 (2.69–3.37); and with age—the RR increased from 0.80 (0.25–2.56) among the <15-year age group to 14.8 (12.9–17.1) among those 45–64 years, then fell to 2.07 (1.20–3.57) among those aged ⩾75. The net effect of these changes is that the gender difference usually observed (i.e. lower rates among females) is not seen. The age relationship means the greatest burden of the disease falls upon those in the age groups who are at the peak of their economic and societal role. The cause of this age–period interaction is complex—those people currently aged 55–75 experienced a very different upbringing to those currently aged 25–45. Whether this age relationship is a period effect will only become clear in the future as the current ‘middle-aged' cohort ages and it becomes clear whether this is an age–period interaction or simply an age–ethnicity interaction.

In New Zealand, the overall relative rate for Maori during the period 2006–2009 was 3.61 (3.27–3.98) and Pacific Peoples 3.89 (3.44–4.39). While the interaction between indigenous group and relative risk remains significant (P<0.001 for interaction), the excess risk among females was more pronounced among Pacific Peoples (female RR 5.23 (4.37–6.27) vs. males RR 3.09 (2.61–3.65)) than among Maori (female RR 4.10 (3.52–4.80) vs male RR 3.31 (2.91–3.76)). Age-related trends were less marked than for Australian indigenous groups (peak RR 10.0 (8.22–12.1) for Maori and RR 13.5 (10.8–17.0) for Pacific Peoples in the 55–64-year age group).

In addition to variation with age and gender, there is considerable variation in ESKD rates within Australia in geographic terms, with higher rates observed among ATSI people living in more remote areas.5 This leads to a need to relocate to receive treatment; in one report 78% of ATSI people living in remote areas relocated to receive RRT.6 It is not clear whether this geographic variation reflects differences in the prevalence of diabetes or other chronic conditions, differences in the rate of progression of CKD, or differential access to treatment. There are some clues: there does not appear to be a major cardiovascular mortality gradient between outer metropolitan and remote areas.7 Another possible factor is the differential uptake of RRT; however, there is little difference between indigenous and non-indigenous groups in the proportion of people who receive RRT in a recent death-certificate-based study.4 Genetic differences have been suggested (thrifty genotype), but there is no empirical evidence to support or refute this as a cause of the geographical variation.

The reported primary renal disease for ESKD in ATSI, Maori, and Pacific Peoples is predominantly diabetic nephropathy (DN). Among ATSI, 60% of incident cases are attributed to DN in 2009 (25% of the non-indigenous group). For New Zealand, 69% of Maori and 65% of Pacific Peoples were reported as DN (in contrast to 21% of the non-indigenous New Zealanders who started RRT). The rates of renal biopsy for DN in both Australia and New Zealand are low—the diagnosis of DN is assigned clinically and is likely to include a number of factors, including hypertensive change and glomerulomegaly.

RENAL REPLACEMENT THERAPY

Australia has a system of universal health care (Medicare). While there is also a system of private health insurance, in the nephrological sector this provides access to some additional hemodialysis facilities in capital cities, but does not affect the basic entitlement to care.

In both Australia and New Zealand, incident patients of indigenous origin are less likely to commence treatment with peritoneal dialysis or a pre-emptive transplant. In 2009, 18% of ATSI people commenced RRT with peritoneal dialysis and 1% with a pre-emptive transplant; in contrast, 25% of non-indigenous people started with peritoneal dialysis and 6% with a pre-emptive transplant. In New Zealand, there are differences between the Maori (where 31% commenced RRT with PD in 2009) and Pacific Peoples (where 22% commenced RRT with PD) compared with 41% for non-indigenous people. Only 1% of Maori and none among the Pacific Peoples started with a pre-emptive transplant compared with 7% for non-indigenous New Zealanders.

Complications of dialysis are more common among indigenous than among non-indigenous people. Technique failure and peritonitis rates are higher among ATSI, Maori, and Pacific islanders than comparable non-indigenous groups. In Australia, remoteness from major cities is a further factor associated with higher rates of peritonitis.8

In 2009, overall peritonitis rates among ATIS were 1.23 (1.07–1.42) episodes per patient-year; for non-indigenous Australians the comparable rate was 0.54 (0.51–0.57) per patient-year.

MORTALITY DURING DIALYSIS TREATMENT

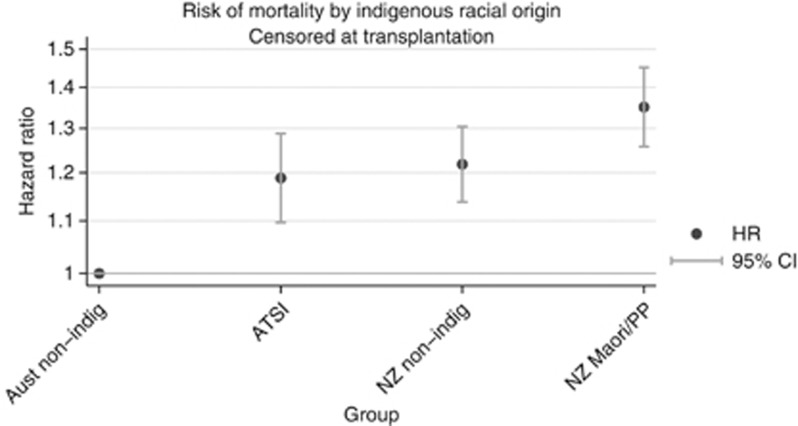

Comparison of the indigenous dialysis populations with the non-indigenous populations in both Australia and New Zealand discloses a number of differences—the indigenous groups are younger, more likely to be female, diabetic, have coronary artery, peripheral vascular, or chronic lung disease, obesity, be referred late for nephrological care, and be current smokers at RRT start. After adjusting for these demographic differences, and comorbidities, there remains a moderate excess mortality risk associated with indigenous racial origin among those who commenced RRT in the period 2000–2009 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Relative mortality of indigenous groups during dialysis treatment, Australia and New Zealand. This analysis includes all incident patients during the period 2000–2009, adjusted for age, diabetes, coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, chronic lung disease, smoking, later referral, and BMI at RRT start, and censored at transplantation on or at 31 December 2009. ATSI=Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islanders.

TRANSPLANTATION

The number of indigenous people transplanted is considerably lower than that of non-indigenous comparators, a situation common to other countries.9 Among people aged less than 60 at RRT start, by 5 years 67% of non-indigenous Australians and 71% of surviving non-indigenous New Zealanders had received a transplant; for ATSI in Australia and Maori and Pacific Peoples in NZ the rates are 26% and 25%, respectively. In Australia during 2009, 737 transplants were performed for non-indigenous recipients, of whom 418 (57%) received kidneys from deceased donors. For indigenous recipients, there were 24 transplants performed for indigenous recipients, 20 (83%) of which were from deceased donors. Similarly, for New Zealand non-indigenous people there were 96 transplants performed (38 (40%) from deceased donors), and 25 transplants to indigenous recipients (16 (64%) from deceased donors). This is partly explained by a higher prevalence of comorbidities, but there are likely to be a number of other factors. Previous studies have suggested both lower rates of placement on the waiting list, and lower rates of transplantation of those on the list.10 Communication issues are important in many settings, with empiric evidence suggesting problems in sharing a mutual understanding during nephrological consultations.11

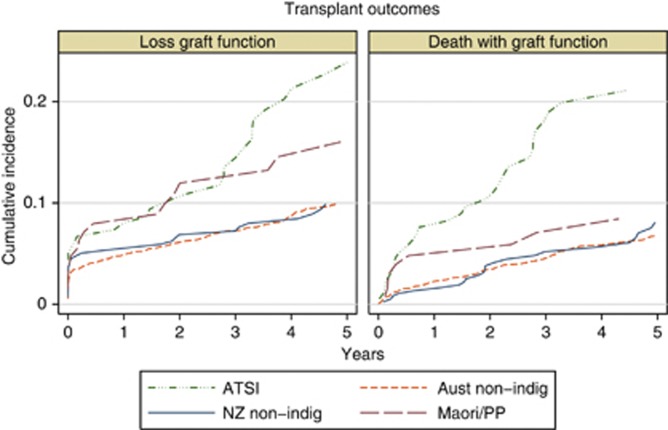

Transplant outcomes among indigenous people are substantially inferior to those among non-indigenous groups. There is a particular excess of death with a functioning transplant, with a continuing increase in difference over time after transplantation (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Cumulative incidence of different types of graft loss in Australia and New Zealand, using a competing-risks approach. The left panel shows loss of graft function (return to dialysis), and the right panel death with a functioning graft. Only first deceased donor grafts (kidney only) are included.

SUMMARY

Indigenous groups in Australia and New Zealand have substantially higher rates of ESKD than non-indigenous people. Importantly, these rates have stabilized in both countries, after a long period of steady increase. There are differences in dialysis modality, rates of transplantation, and outcomes among both dialysis and transplant patients.

Acknowledgments

The enormous contribution of patients and staff in renal units throughout Australia and New Zealand in contributing and submitting data to the ANZDATA Registry is gratefully acknowledged.

The author declared no competing interests.

References

- Statistics New Zealand Quickstats about New Zealand's population and dwellings18 May 2007. Available from: http://www.stats.govt.nz/~/media/Statistics/Census/2006-reports/quickstats-subject/Population-Dwellings/qstats-about-nzs-population-and-dwellings-2006-census.pdf (cited 31 March 2012).

- ANZDATA Registry In: McDonald SP, Hurst K (eds).Thirty-fourth Report: Methods and Definitions ANZDATA Registry: Adelaide; 2011, p vii. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald SP, Russ GR. The burden of end stage renal disease (ESRD) among indigenous peoples in Australia & New Zealand. Kidney Int. 2003;63 (Suppl s83:s123–s127. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.63.s83.26.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare End-Stage Kidney Disease in Australia: Total Incidence, 2003–2007Cat. no. PHE 143. AIHW: Canberra, 2011.

- Cass A, Cunningham J, Wang Z, et al. Regional variation in the incidence of end-stage renal disease in indigenous Australians. Med J Aust. 2001;175:24–27. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston-Thomas A, Cass A, O'Rourke P. Kidney disease in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Aboriginal Islander Health Work J. 2007;18:3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Andreasyan K, Hoy WE. Recent patterns in chronic disease mortality in remote living Indigenous Australians. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:483. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim WH, Boudville N, McDonald SP, et al. Remote indigenous peritoneal dialysis patients have higher risk of peritonitis, technique failure, all-cause and peritonitis-related mortality. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:3366–3372. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeates KE, Cass A, Sequist TD, et al. Indigenous people in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States are less likely to receive renal transplantation. Kidney Int. 2009;76:659–664. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald SP, Russ GR. Current incidence, treatment patterns and outcome of end-stage renal disease among indigenous groups in Australia and New Zealand. Nephrology (Carlton) 2003;8:42–48. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1797.2003.00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cass A, Lowell A, Christie M, et al. Sharing the true stories: improving communication between Aboriginal patients and healthcare workers. Med J Aust. 2002;176:466–470. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]