- 9.1: For the following infection-related GN, we suggest appropriate treatment of the infectious disease and standard approaches to management of the kidney manifestations: (2D)

- poststreptococcal GN;

- infective endocarditis-related GN;

- shunt nephritis.

INTRODUCTION

This chapter provides recommendations for the treatment of infection-associated GN, which may occur in association with bacterial, viral, fungal, protozoal, and helminthic infection (Table 21). The cost implications for global application of this guideline are addressed in Chapter 2.

Table 21. Infections associated with glomerulonephritis.

| Bacterial | Viral |

| Mycobacterium leprae, M. tuberculosis | Hepatitis B and C |

| Treponema pallidum | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| Salmonella typhi, S. paratyphi, S. typhimurium | Epstein-Barr virus |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae, S. virdans, S. pyogenes | Coxsackie B |

| Staphyloccoccus aureus, S. epidermidis, S. albus | ECHO virus |

| Leptospira speciesa | Cytomegalovirus |

| Yersinia enterocoliticaa | Varicella zoster |

| Neisseria meningitidis, Neisseria gonorrhoeaea | Mumps |

| Corynebacterium diphtheriaea | Rubella |

| Coxiella burnettiia | Influenza |

| Brucella abortusa | |

| Listeria monocytogenesa | |

| Fungal | Helminthic |

| Histoplasma capsulatuma | Schistosoma mansoni, S. japonicum, S. haematobium |

| Candidaa | Wuchereria bancrofti |

| Coccidiodes immitisa | Brugia malayi |

| Loa loa | |

| Protozoal | Onchocerca volvulus |

| Plasmodium malariae, P. falciparum | Trichinella spiralisa |

| Leishmania donovani | |

| Toxoplasma gondii | |

| Trypanosoma cruzi, T. bruci | |

| Toxocara canisa | |

| Strongyloides stercoralisa |

ECHO, enteric cytopathic human orphan; GN, glomerulonephritis.

Only case reports documented.

BACTERIAL INFECTION–RELATED GN

BACKGROUND AND RATIONALE

The prototype for bacterial infection-related GN (also called postinfectious GN) is poststreptococcal GN, which most often occurs in children following a pharyngeal or cutaneous infection (impetigo) caused by a particular nephritogenic strain of Streptococci, and usually has a favorable outcome.

However, in the last decades the spectrum of postinfectious GN has changed. The incidence of poststreptococcal GN, particularly in its epidemic form, has progressively declined in industrialized countries. Recent series reported that streptococcal infections accounted for only 28–47% of acute GN, Staphylococcus aureus or Staphylococcus epidermidis being isolated in 12–24% of cases and Gram-negative bacteria in up to 22% of cases.330, 331, 332 Bacterial endocarditis and shunt infections are also frequently associated with postinfectious GN. Moreover, the atypical postinfectious GN tends to affect mainly adults who are immunocompromised, e.g., in association with alcoholism, diabetes, and drug addiction. While spontaneous recovery within a few weeks is still the rule in children affected by the typical poststreptococcal GN, the prognosis in immunocompromised adults with postinfectious GN is significantly worse, with less than 50% in complete remission after a long follow-up.333

POSTSTREPTOCOCCAL GN

BACKGROUND AND RATIONALE

The diagnosis of poststreptococcal GN requires the demonstration of antecedent streptococcal infection in a patient who presents with acute GN. Nephritis may follow 7–15 days after streptococcal tonsillitis and 4–6 weeks after impetigo.334

The nature of the nephritogenic streptococcal antigen is still controversial.334, 335, 336 Kidney biopsy is not indicated unless there are characteristics that make the diagnosis doubtful, or to assess prognosis and/or for potential therapeutic reasons. The kidney histology shows acute endocapillary GN with mesangial and capillary granular immune deposition.

The clinical manifestations of acute nephritic syndrome usually last less than 2 weeks. Less than 4% of children with poststreptococcal GN have massive proteinuria, and occasionally a patient develops crescentic GN with rapidly progressive kidney dysfunction. Serum C3 values usually return to normal by 8–10 weeks after recognition of the infection. Persistent hypocomplementemia beyond 3 months may be an indication for a renal biopsy, if one has not already been performed. A lesion of MPGN is commonly found in persistently hypocomplementemic GN.

The short-term prognosis of the acute phase of poststreptococcal GN is excellent in children; however, in elderly patients, mortality in some series is as high as 20%. Although the long-term prognosis of poststreptococcal GN is debated, the incidence of ESRD in studies with 15 years of follow-up is less than 1%, with the exception being that long-term prognosis is poor in elderly patients who develop persistent proteinuria.333, 334

Well-documented streptococcal infection should be treated with penicillin, or erythromycin if the patient is allergic to penicillin, to resolve streptococcal infection and prevent the spread of the nephritogenic streptococcus among relatives or contacts. However, antibiotics are of little help for reversing GN, as the glomerular lesions induced by immune complexes are already established.

The management of acute nephritic syndrome, mainly in adults, requires hospital admission if features of severe hypertension or congestive heart failure are present. Hypertension and edema usually subside after diuresis is established. Adult patients persisting with urinary abnormalities beyond 6 months, especially if proteinuria >1 g/d, should receive ACE-I or ARBs, as in other proteinuric glomerular diseases (see Chapter 2). The long-term prognosis is worse in patients, mainly adults, who have persistent proteinuria after 6 months.337

Pulses of i.v. methylprednisolone can be considered in patients with extensive glomerular crescents and rapidly progressive GN, based on extrapolation from other rapidly progressive and crescentic GNs, although there is no evidence from RCTs.

RESEARCH RECOMMENDATIONS

An RCT is needed to evaluate the treatment of crescentic poststreptococcal GN with corticosteroids.

Research is needed to determine the nature of the streptococcal antigen, as a basis for developing immunoprophylactic therapy.

GN ASSOCIATED WITH INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS

BACKGROUND AND RATIONALE

The natural history of GN associated with infective endocarditis has been significantly altered with the changing epidemiology of the disorder, and with the use of antibiotics.337, 338, 339, 340

In USA, infective endocarditis is diagnosed in approximately 40 cases per million every year, and the disease is increasingly frequent in elderly individuals and in patients with no underlying heart disease. i.v. drug usage, prosthetic heart valves, and structural heart disease are risk factors. Staphylococcus aureus has replaced Streptococcus viridans as the leading cause of infective endocarditis. The incidence of GN associated with Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis ranges from 22% to 78%, the highest risk being among i.v. drug users. Focal and segmental proliferative GN, often with focal crescents, is the most typical finding. Some patients may exhibit a more diffuse proliferative endocapillary lesion with or without crescents.337, 338, 339, 340

The immediate prognosis of the GN is good, and is related to the prompt eradication of the infection, using appropriate antibiotics for 4–6 weeks.

RESEARCH RECOMMENDATION

Multicenter studies are needed to determine the incidence, prevalence, and long-term prognosis of infective endocarditis–related GN.

SHUNT NEPHRITIS

BACKGROUND AND RATIONALE

Shunt nephritis is an immune complex–mediated GN that develops as a complication of chronic infection on ventriculoatrial or ventriculojugular shunts inserted for the treatment of hydrocephalus.341

The diagnosis is based on clinical evidence of kidney disease (most commonly, microscopic hematuria and proteinuria, frequently in the nephrotic range, occasionally elevated SCr and hypertension) with prolonged fever or signs of chronic infection, in a patient with a ventriculovascular shunt implanted for treatment of hydrocephalus. The histologic findings are typically type 1 MPGN, with granular deposits of IgG, IgM, and C3, and electron-dense mesangial and subendothelial deposits.

The renal outcome of shunt nephritis is good if there is early diagnosis and treatment of the infection. Ventriculovascular shunts may become infected in about 30% of cases. GN may develop in 0.7–2% of the infected ventriculovascular shunts in an interval of time ranging from 2 months to many years after insertion. The infecting organisms are usually Staphylococcus epidermidis or Staphylococcus aureus. In contrast to ventriculovascular shunts, ventriculoperitoneal shunts are rarely complicated with GN.

A late diagnosis, resulting in delays in initiating antibiotic therapy and in removing the shunt, results in a worse renal prognosis.

RESEARCH RECOMMENDATION

Multicenter observational studies are needed to determine the incidence, prevalence, and long-term prognosis of shunt nephritis.

- 9.2: Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection–related GN (Please also refer to the published KDIGO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention, Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of Hepatitis C in Chronic Kidney Disease.342)

- 9.2.1: For HCV-infected patients with CKD Stages 1 or 2 and GN, we suggest combined antiviral treatment using pegylated interferon and ribavirin as in the general population. (2C) [based on KDIGO HCV Recommendation 2.2.1]

- 9.2.1.1: Titrate ribavirin dose according to patient tolerance and level of renal function. (Not Graded)

- 9.2.2: For HCV-infected patients with CKD Stages 3, 4, or 5 and GN not yet on dialysis, we suggest monotherapy with pegylated interferon, with doses adjusted to the level of kidney function. (2D) [based on KDIGO HCV Recommendation 2.2.2]

- 9.2.3: For patients with HCV and mixed cryoglobulinemia (IgG/IgM) with nephrotic proteinuria or evidence of progressive kidney disease or an acute flare of cryoglobulinemia, we suggest either plasmapheresis, rituximab, or cyclophosphamide, in conjunction with i.v. methylprednisolone, and concomitant antiviral therapy. (2D)

BACKGROUND

HCV infection is a major public health problem, with an estimated 130–170 million people infected worldwide.343, 344, 345 HCV frequently causes extrahepatic manifestations, including mixed cryoglobulinemia, lymphoproliferative disorders, Sjögren's syndrome, and kidney disease. A major concern is the lack of safe and effective drugs to treat HCV-infected patients with CKD.346 Unfortunately, there are no large-scale clinical trials in patients with HCV-associated kidney disease; thus, evidence-based treatment recommendations cannot be made in this patient population. However, we have extrapolated HCV treatment from the non-CKD population, with the appropriate and necessary dose adjustments.

Kidney involvement due to HCV is most commonly associated with type II cryoglobulinemia, and is clinically manifested by proteinuria, microscopic hematuria, hypertension, and mild to moderate kidney impairment.347, 348

On kidney biopsy, a type I MPGN pattern of injury is the most common pathological finding.349 Vasculitis of the small- and medium-sized renal arteries can also be present. Immunofluorescence usually demonstrates deposition of IgM, IgG, and C3 in the mesangium and capillary walls. On electron microscopy, subendothelial immune complexes are usually seen and may have an organized substructure suggestive of cryoglobulin deposits.348, 350 Besides MPGN, other forms of glomerular disease have been described in patients with HCV, including IgAN, MN, postinfectious GN, thrombotic microangiopathies, FSGS, and fibrillary and immunotactoid GN.348, 349, 350, 351, 352, 353, 354

Patients with type II cryoglobulinemia (mixed polyclonal IgG and monoclonal IgM [Rheumatoid-factor positive] cryoglobulins) should be tested for HCV. Patients with proteinuria and cryoglobulinemia should be tested for HCV RNA even in the absence of clinical and/or biochemical evidence of liver disease. Similarly, HCV-infected patients should be tested at least annually for proteinuria, hematuria, and eGFR to detect possible HCV-associated kidney disease. Practice guidelines for treatment of HCV infection in general have been recently published.355 For detailed information regarding treatment of HCV-mediated kidney disease the reader is also referred to the recently published KDIGO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention, Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of Hepatitis C in Chronic Kidney Disease.342

RATIONALE

There is low-quality evidence to recommend treatment of HCV-associated GN. Treatment should be focused on reducing or eliminating HCV replication, and reducing the formation and glomerular deposition of HCV-containing immune complexes (including cryoglobulins).

There is low-quality evidence to recommend dose adjustments for interferon and ribavirin based on level of kidney function.

There is very low–quality evidence to suggest that patients with HCV-associated GN and severe kidney manifestations require additional treatment with immunosuppression and/or corticosteroids and/ or plasma exchange.

The best long-term prognostic indicator of HCV-associated GN is sustained virologic response (defined as HCV RNA clearance from serum) for at least 6 months after cessation of therapy. In patients with normal kidney function, this aim can be best achieved by the use of pegylated interferon-α-2a/2b in combination with ribavirin, which results in sustained virological response rates of 45–50% in genotypes 1 and 4, and 70–80% in genotypes 2 and 3 in HVC-monoinfected patients. This represents the current standard of care for HCV infection.342, 355

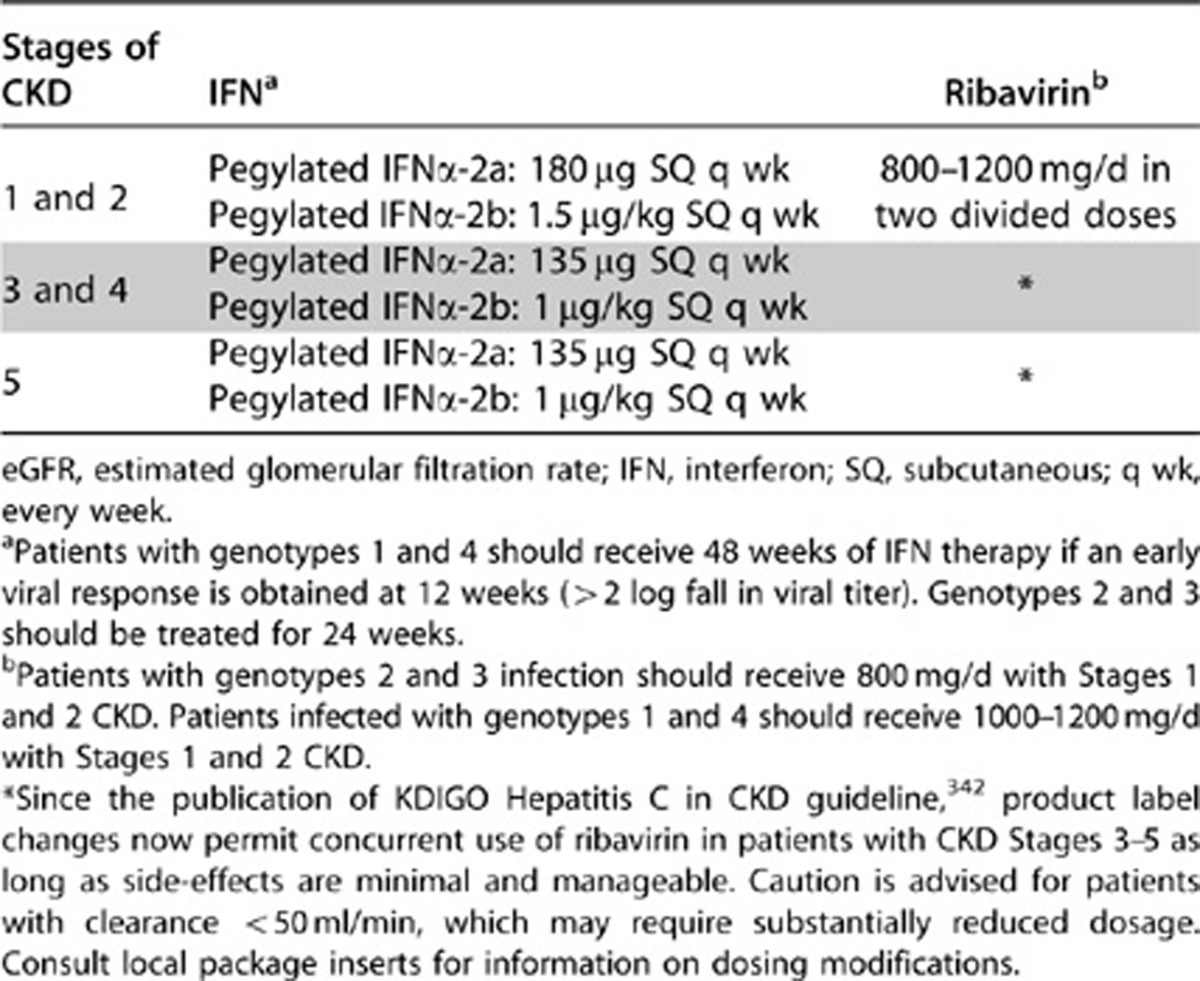

Treatment regimens for HCV-associated GN and the doses of individual agents will vary with the severity of the kidney disease. No dose adjustment is needed for patients with eGFR >60 ml/min.356, 357, 358

There is a paucity of information regarding treatment of HCV-infected patients with GFR <60 ml/min but not yet on dialysis (CKD stages 3–5). The suggested doses (based on expert opinion, not evidence) are pegylated interferon-α-2b, 1 μg/kg subcutaneously once weekly or pegylated interferon-α-2a, 135 μg subcutaneously once weekly, together with ribavirin 200–800 mg/d in two divided doses, starting with the low dose and increasing gradually, as long as side-effects are minimal and manageable (see Table 22). Hemolysis secondary to ribavirin very commonly limits its dosage or prevents its use in patients with CKD.

Table 22. Treatment of HCV infection according to stages of CKD.

Monotherapy with interferon-α has been used in cryoglobulinemic GN with complete clearance of HCV RNA and improved kidney function; however, recurrence of viremia and relapses of kidney disease were universally observed after interferon was discontinued.359, 360 Subsequent studies with interferon-α monotherapy360, 361, 362, 363 have yielded mixed results.360 Treatment with interferon-α may exacerbate cryoglobulinemic vasculitis.364, 365 Thus, it is recommended that interferon -α should be started after the acute flare has been controlled with immunosuppressive agents.366

Better outcomes have been achieved by combined use of interferon-α with ribavirin367, 368, 369, 370 and pegylated interferon with ribavirin.366, 370, 371, 372, 373, 374 In a recent meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials comparing the efficacy and safety of antiviral vs. immunosuppressive therapy (corticosteroids alone or in combination with cyclophosphamide) in patients with HCV-associated GN, proteinuria decreased more (odds ratio 3.86) after interferon therapy (3 MU thrice weekly for at least 6 months).375 However, both treatments failed to significantly improve kidney function. Recently published KDIGO guidelines for treatment of viral hepatitis in patients with kidney disease suggest that patients with moderate proteinuria and slowly progressive kidney disease can be treated with a 12-month course of standard interferon-α or pegylated interferon-α-2a with dose adjusted as described below plus ribavirin, with or without erythropoietin support, depending on the level of hemoglobin.342 Ribavirin dose needs to be titrated according to patient tolerance; caution is advised for patients with clearance <50 ml/min which may require substantially reduced dosage.

There is very low–quality evidence that patients with nephrotic-range proteinuria and/or rapidly progressive kidney failure or an acute flare of cryoglobulinemia, should receive additional therapy with either plasmapheresis (3 L of plasma thrice weekly for 2–3 weeks), rituximab (375 mg/m2 once a week for 4 weeks), or cyclophosphamide (2 mg/kg/d for 2–4 months) plus i.v. methylprednisolone 0.5–1 g/d for 3 days.342 There are no comparative data to favour any one of these three additional therapies. Corticosteroids may lead to increases in HCV viral load.376, 377

Case reports have suggested remarkable reduction in proteinuria and stabilization of kidney function in response to rituximab in patients with cryoglobulinemic vasculitis.378, 379 Although HCV viremia increased modestly in some patients, it remained unchanged or decreased in others and the overall treatment was considered safe.380 Observations in 16 patients with severe refractory HCV-related cryoglobulinemia vasculitis treated with rituximab in combination with pegylated interferon-α-2b and ribavirin also showed good response.381 Symptoms usually reappear with reconstitution of peripheral B cells. The long-term safety of multiple courses of rituximab in patients with HCV is unknown. It remains debatable whether antiviral therapy should be commenced as soon as immunosuppression is begun or delayed until a clinical remission (complete or partial) is evident.382, 383, 384

There is a paucity of controlled studies available in HCV-associated GN; most studies are retrospective analyses with small sample sizes. Most of the available evidence comes from studies of patients with significant proteinuria, hematuria, or reduced kidney function.

RESEARCH RECOMMENDATIONS

- Epidemiologic studies are needed to determine:

- the prevalence and types of glomerular lesions in HCV-infected patients;

- whether there are true associations between HCV infection and GN other than MPGN (e.g., IgAN).

An RCT is needed to evaluate corticosteroids plus cyclophosphamide in addition to antiviral therapy in HCV-associated GN.

An RCT is needed to evaluate rituximab in addition to antiviral therapy in HCV-associated GN.

- 9.3: Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection–related GN

- 9.3.1: We recommend that patients with HBV infection and GN receive treatment with interferon-α or with nucleoside analogues as recommended for the general population by standard clinical practice guidelines for HBV infection (see Table 23). (1C)

- 9.3.2: We recommend that the dosing of these antiviral agents be adjusted to the degree of kidney function. (1C)

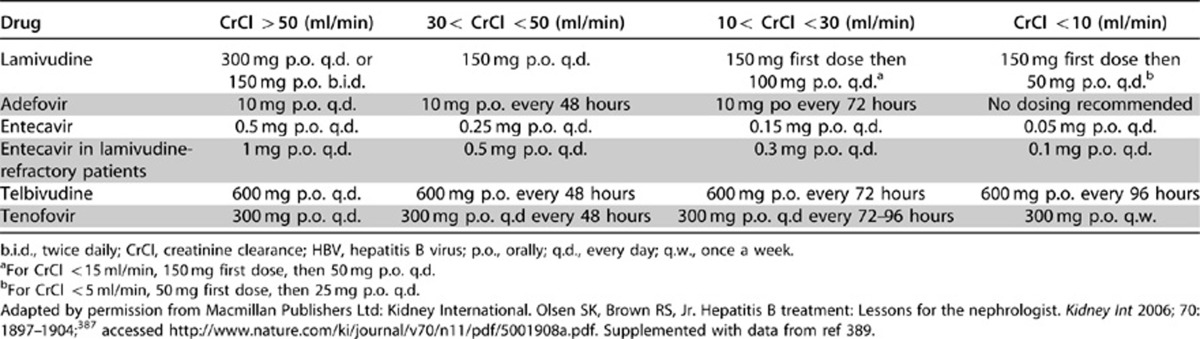

Table 23. Dosage adjustment of drugs for HBV infection according to kidney function (endogenous CrCl).

BACKGROUND

Approximately one-third of the world's population has serological evidence of past or present infection with HBV, and 350 million people are chronically infected, making it one of the most common human pathogens.385, 386 The spectrum of disease and natural history of chronic HBV infection is diverse and variable, ranging from a low viremic inactive carrier state to progressive chronic hepatitis, which may evolve to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. It is not possible to predict which patients with HBV infection are more likely to develop kidney disease.387

HBV-associated patterns of GN include MN, MPGN, FSGS and IgAN. MN is the most common form of HBV-mediated GN, especially in children. The diagnosis of HBV-mediated GN requires detection of the virus in the blood and the exclusion of other causes of glomerular disease. In children, HBV-mediated GN has a favorable prognosis, with high spontaneous remission rate. In adults, HBV-mediated GN is usually progressive. Patients with nephrotic syndrome and abnormal liver function tests have an even worse prognosis, with >50% progressing to ESRD in the short term.388 There are no RCT studies on the treatment of HBV-mediated GN, so evidence-based treatment recommendations cannot be made. Clinical practice guidelines on the management of chronic hepatitis B have been recently published in Europe and in the USA, but do not include specific recommendations on HBV-mediated kidney disease.385, 386

RATIONALE

Treatment of HBV-associated GN with interferon or nucleoside analogues is indicated.

Several drugs are now available for the treatment of chronic HBV infection (see Table 23). The efficacy of these drugs has been assessed in an RCT at 1 year (2 years with telbivudine). Longer follow-up (up to 5 years) is available for lamivudine, adefovir, entecavir, telbivudine, and tenofovir in patient subgroups.385 However, there are no data to indicate the effect of these treatments for HBV infection on the natural history of HBV-related GN. Treatment of patients with HBV infection and GN should be conducted according to standard clinical practice guidelines for HBV infection. Nephrotoxicity of some of the nucleoside analogues (adefovir and tenofovir) can be of concern.

The heterogeneity of patients with HBV infection (e.g., degree of liver function impairment, extent of extrahepatic involvement) creates substantial complexity in establishing treatment guidelines in patients with HBV-mediated kidney disease.

RESEARCH RECOMMENDATIONS

RCTs are needed to establish the most effective antiviral treatment regimen in modifying the progression of HBV-associated GN. Studies will need to account for the extrarenal disease involvement, as well as evaluate varying drug combinations, including timing and duration of therapy.

RCTs in children should be evaluated separately in view of the higher rate of spontaneous remission in HBV-associated GN.

- 9.4: Human Immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection–related glomerular disorders

- 9.4.1: We recommend that antiretroviral therapy be initiated in all patients with biopsy-proven HIV-associated nephropathy, regardless of CD4 count. (1B)

BACKGROUND

Approximately 5 million people a year are infected with HIV worldwide.390 Kidney disease is a relatively frequent complication in patients infected with HIV.

Human immunodeficiency virus–associated nephropathy (HIVAN) is the most common cause of CKD in patients with HIV-1, and is mostly observed in patients of African descent,391, 392 perhaps related to susceptibility associated with genetic variation at the APOL1 gene locus on chromosome 22, closely associated with the MYH9 locus.164,393 Untreated, HIVAN rapidly progresses to ESRD. Typical HIVAN pathology includes FSGS, often with a collapsing pattern, accompanied by microcystic change in tubules. There are usually many tubuloreticular structures seen on electron microscopy. In addition to HIVAN, a number of other HIV-associated kidney diseases have been described.391, 394, 395 In patients with HIV, proteinuria and/or decreased kidney function is associated with increased mortality and worse outcomes.396 Data from a number of RCTs suggest that highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) is beneficial in both preservation and improvement of kidney function in patients with HIV.397, 398, 399 Patients with kidney dysfunction at start of HAART have the most dramatic improvements in kidney function.400, 401 A decrease in HIV viral load during HAART is associated with kidney function improvement, while an increase in viral load is associated with worsening kidney function.402, 403, 404

RATIONALE

There is low-quality evidence to suggest a kidney biopsy is necessary to define the specific type of kidney diseases present in patients with HIV infection.

HAART may be effective in HIVAN, but it is not effective in other GN associated with HIV infection.

Causes of kidney disease, other than HIVAN, that occur in patients with HIV infection include diabetic nephropathy, thrombotic microangiopathies, cryoglobulinemia, immune complex GN, an SLE-like GN, or amyloidosis (see Table 24).394, 395, 405, 406 More than a third of the patients with HIV who underwent a kidney biopsy had diabetic nephropathy; or MN, MPGN, IgAN, or another pattern of immune-complex GN.395, 407 In patients with HIV infection, many of these pathologies can mimic HIVAN, but each condition requires a different therapy.391, 394, 395, 408 Studies in HIV-infected patients with kidney disease from Africa showed a high prevalence of HIVAN, but other forms of GN and interstitial nephritis were also present (see Table 24).409, 410 Cohen and Kimmel recently reviewed the rationale for a kidney biopsy in the diagnosis of HIV-associated kidney disease.391, 411

Table 24. The spectrum of kidney disease in HIV-infected patients.

| • HIVAN-collapsing FSGS |

| • Arterionephrosclerosis |

| • Immune-complex GN |

| –MPGN pattern of injury |

| –Lupus-like GN |

| • Idiopathic FSGS |

| • HCV and cryoglobulinemia |

| • Thrombotic microangiopathies |

| • Membranous nephropathy |

| –HBV-mediated |

| –Malignancy |

| • Minimal-change nephropathy |

| • IgAN |

| • Diabetic nephropathy |

| • Postinfectious GN |

| –Infectious endocarditis |

| –Other infections: Candida, Cryptococcus |

| • Amyloidosis |

| • Chronic pyelonephritis |

| • Acute or chronic interstitial nephritis |

| • Crystal nephropathy |

| –Indinavir, atazanavir, i.v. acyclovir, sulfadiazine |

| • Acute tubular necrosis |

| • Proximal tubulopathy (Fanconi syndrome) |

| –Tenofovir |

FSGS, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis; GN, glomerulonephritis; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIVAN, human immunodeficiency virus–associated nephropathy; IgAN, immunoglobulin A nephropathy; MPGN, mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis.

Observational studies and data from uncontrolled or retrospective studies398, 399, 412, 413, 414, 415 and from an RCT397 suggest that HAART (defined as combination therapy with three or more drugs) is beneficial in both preservation and improvement of kidney function in patients with HIVAN. Since the introduction of HAART in the 1990s, there has also been a substantial reduction in the incidence of HIVAN.416 In multivariate analysis, HIVAN risk was reduced by 60% (95% CI −30% to −80%) by use of HAART, and no patient developed HIVAN when HAART had been initiated prior to the development of acquired immune deficiency syndrome.416 The use of HAART has also been associated with improved kidney survival in patients with HIVAN.417 Antiviral therapy has been associated with GFR improvements in HIV patients with both low CD4 lymphocyte counts and impaired baseline kidney function, supporting an independent contribution of HIV-1 replication to chronic kidney dysfunction in advanced HIV disease.398

Early observational studies suggested a benefit for ACE-I.418 A number of retrospective, observational, or uncontrolled studies conducted before or during the initial phases of HAART reported variable success with the use of corticosteroids in patients with HIV-associated kidney diseases.419, 420, 421 There is only one study using cyclosporine in 15 children with HIV and nephrotic syndrome.422 These early observational studies suggested a benefit for ACE-I and corticosteroids in HIV-mediated kidney disease, but the studies were prior to introduction of HAART, and in the era of modern HAART therapy, it is unclear what the potential benefits are, if any, of the use of corticosteroids or cyclosporine in the treatment of patients with HIVAN or other HIV-related kidney diseases. It is not known whether this benefit remains in the context of current management.418

There is no RCT that evaluates the value of HAART therapy in patients with HIVAN.423 There is very low–quality evidence to suggest that HAART may be of benefit in patients with HIV-associated immune-complex kidney diseases and thrombotic microangiopathies.391, 394, 411 There are recent comprehensive reviews of HIV and kidney disease that describe current knowledge and gaps therein.424, 425

RESEARCH RECOMMENDATIONS

RCTs are needed to evaluate the efficacy of HAART in HIVAN and other HIV-associated glomerular diseases. Long-term follow-up is needed to determine if kidney damage in susceptible individuals is halted or merely slowed by HAART, particularly when control of viremia is incomplete or intermittent.

An RCT is needed to evaluate the role of corticosteroids in combination with HAART in the treatment of HIV-associated kidney diseases.

An RCT is needed to determine if benefits of RAS blockade are independent of HAART therapy in patients with HIVAN and other HIV-mediated kidney diseases.

- 9.5: Schistosomal, filarial, and malarial nephropathies

- 9.5.1: We suggest that patients with GN and concomitant malarial, schistosomal, or filarial infection be treated with an appropriate antiparasitic agent in sufficient dosage and duration to eradicate the organism. (Not Graded)

- 9.5.2: We suggest that corticosteroids or immunosuppressive agents not be used for treatment of schistosomal-associated GN, since the GN is believed to be the direct result of infection and the attendant immune response to the organism. (2D)

- 9.5.3: We suggest that blood culture for Salmonella be considered in all patients with hepatosplenic schistosomiasis who show urinary abnormalities and/or reduced GFR. (2C)

- 9.5.3.1: We suggest that all patients who show a positive blood culture for Salmonella receive anti-Salmonella therapy. (2C)

SCHISTOSOMAL NEPHROPATHY

BACKGROUND

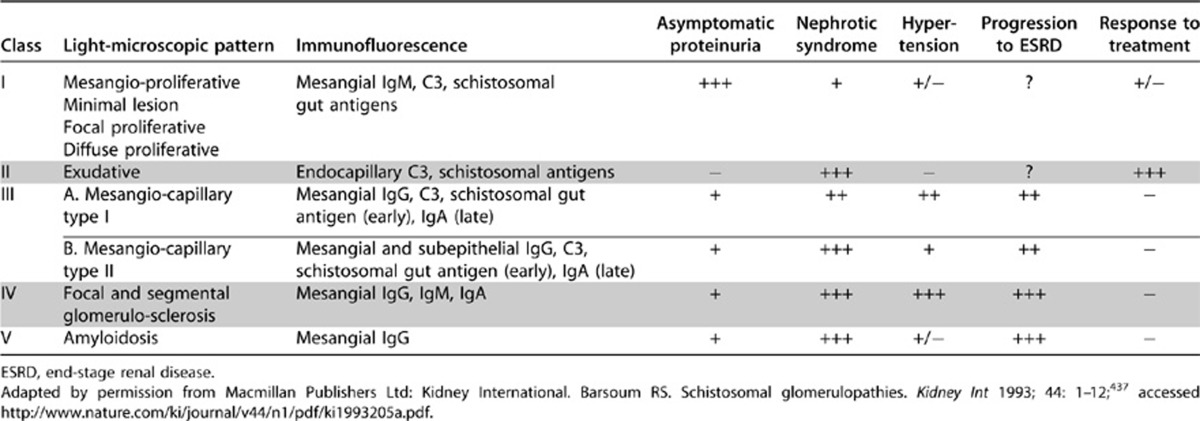

Schistosomiasis (syn. Bilharziasis), a chronic infection by trematodes (blood flukes), is encountered in Asia, Africa, and South America.426, 427 S. mansoni and S. japonicum cause glomerular lesions in experimental studies, but clinical glomerular disease has been described most frequently in association with hepatosplenic schistosomiasis produced by S. mansoni.428, 429, 430, 431, 432, 433, 434, 435, 436 A classification of schistosomal glomerulopathies is given in Table 25. It should be recognized that, in highly endemic areas, the association of GN with schistosomiasis may be coincidental rather than causal.

Table 25. A clinicopathological classification of schistosomal glomerulopathy.

RATIONALE

The incidence of GN in schistosomiasis is not well defined. Hospital-based studies have shown overt proteinuria in 1–10% and microalbuminuria in about 22% of patients with hepatosplenic schistosomiasis due to S. mansoni.437, 438 Sobh et al.439 documented asymptomatic proteinuria in 20% patients with “active” S. mansoni infection. A field study in an endemic area of Brazil showed only a 1% incidence of proteinuria.440 However, histological studies have documented glomerular lesions in 12 – 50% of cases.430, 435

GN is most commonly seen in young adults, and males are affected twice as frequently as females. In addition to nephrotic syndrome, eosinophiluria is seen in 65% of cases and hypergammaglobulinemia in 30%.441 Hypocomplementemia is common. Several studies have shown new-onset or worsening of nephrotic syndrome in the presence of coinfection with Salmonella.442

Several patterns of glomerular pathology have been described (see Table 25). Class I is the earliest and most frequent lesion. Class II lesion is more frequent in patients with concomitant Salmonella (S. typhi, S. paratyphi A, or S. typhimurium) infection.443, 444

Praziquantel, given in a dose of 20 mg/kg three times for 1 day, is effective in curing 60–90% patients with schistosomiasis. Oxamiquine is the only alternative for S. mansoni infection.445 Successful treatment helps in amelioration of hepatic fibrosis and can prevent development of glomerular disease. Established schistosomal GN, however, does not respond to any of these agents.

Steroids, cytotoxic agents, and cyclosporine are ineffective in inducing remission.446 In one RCT, neither prednisolone nor cyclosporine, given in combination with praziquantel and oxamiquine were effective in inducing remissions in patients with established schistosomal GN.447

Treatment of coexistent Salmonella infection favorably influences the course of GN. In a study of 190 patients with schistosomiasis, 130 were coinfected with Salmonella. All of them showed improvement in serum complement levels, CrCl, and proteinuria following antibilharzial and anti-Salmonella treatment, either together or sequentially.448 Other studies have shown disappearance of urinary abnormalities following anti-Salmonella therapy alone.442, 444 The prognosis is relatively good with class I and II schistosomal GN, provided sustained eradication of Schistosoma and Salmonella infection can be achieved, whereas class IV and V lesions usually progress to ESRD despite treatment.446, 449, 450 The association of Salmonella infection with schistosomal GN is not observed in all geographical areas.451

RESEARCH RECOMMENDATION

Studies are required to evaluate the precise contribution of Salmonella infection to schistosomal nephropathy, and the value of treating these two infections separately or together on the outcome.

FILARIAL NEPHROPATHY

BACKGROUND AND RATIONALE

Filarial worms are nematodes that are transmitted to humans through arthropod bites, and dwell in the subcutaneous tissues and lymphatics. Clinical manifestations depend upon the location of microfilariae and adult worms in the tissues. Of the eight filarial species that infect humans, glomerular disease has been reported in association with Loa loa, Onchocerca volvulus, Wuchereria bancrofti, and Brugia malayi infections in Africa and some Asian countries.452, 453, 454, 455, 456

Glomerular involvement is seen in a small number of cases. Light microscopy reveals a gamut of lesions, including diffuse GN and MPGN, membranoproliferative GN, minimal-change and chronic sclerosing GN, and the collapsing variant of FSGS.457 Microfilariae may be found in the arterioles, glomerular and peritubular capillary lumina, tubules, and interstitium.457 Immunofluorescence and electron microscopy show immune deposits along with worm antigens and structural components.456, 458

Urinary abnormalities have been reported in 11–25% and nephrotic syndrome is seen in 3–5% of patients with loiasis and onchocerciasis, especially those with polyarthritis and chorioretinitis.456, 459 Proteinuria and/or hematuria was detected in over 50% of cases with lymphatic filariasis; 25% showed glomerular proteinuria.460, 461 A good response (diminution of proteinuria) is observed following antifilarial therapy in patients with non-nephrotic proteinuria and/or hematuria. The proteinuria can increase and kidney functions worsen following initiation of diethylcarbamazepine or ivermectin,461, 462 probably because of an exacerbation of the immune process secondary to antigen release into circulation after death of the parasite.463

The response is inconsistent in those with nephrotic syndrome, and deterioration of kidney function may continue, despite clearance of microfilariae with treatment. Therapeutic apheresis has been utilized to reduce the microfilarial load before starting diethylcarbamazepine to prevent antigen release.464

The incidence, prevalence, and natural history of glomerular involvement in various forms of filariasis are poorly documented. This condition is usually found in areas with poor vector control and inadequate health-care facilities. Similarly, the treatment strategies have not been evaluated.

RESEARCH RECOMMENDATION

• Epidemiological studies of kidney involvement in regions endemic for these conditions are required. The effect of population-based treatment with filaricidal agents on the course of kidney disease should be studied.

MALARIAL NEPHROPATHY

BACKGROUND AND RATIONALE

Infection with Plasmodium falciparum usually results in AKI or proliferative GN. Chronic infection with the protozoal malarial parasites Plasmodium malariae (and, to a lesser extent, Plasmodium vivax or ovale) has been associated with a variety of kidney lesions, including MN and membranoproliferative GN.465 In the past, this has been known as “quartan malarial nephropathy”.465, 466 Nephrotic syndrome, sometimes with impaired kidney function, is a common clinical manifestation; it is principally encountered in young children. The glomerular lesions are believed to be caused by deposition of immune complexes containing antigens of the parasite, but autoimmunity may participate as well. The clinical and morphological manifestations vary from country to country.467 Nowadays, the lesion is much less common, and most children in the tropics with nephrotic syndrome have either MCD or FSGS, rather than malarial nephropathy.467, 468 HBV and HIV infection and streptococcal-related diseases are also now more common causes of nephrotic syndrome than malarial nephropathy in Africa.467, 468, 469

There are limited observational studies and no RCTs for an evidence-based treatment strategy for malarial nephropathy. Patients with GN and concomitant infection with Plasmodium species (typically Plasmodium malariae) should be treated with an appropriate antimalarial agent (such as chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine) for suffcient duration to eradicate the organism from blood and hepatosplenic sites. Observational studies have suggested improvement in clinical manifestations in some—but not all—patients, following successful eradication of the parasitic infection. There does not appear to be any role for steroids or immunosuppressant therapy in malarial nephropathy,465, 466 although controlled trials are lacking. Dosage reductions of chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine may be needed in patients with impaired kidney function.

RESEARCH RECOMMENDATIONS

Studies of the incidence and prevalence of malarial nephropathy, and its response to antimalarial therapy are needed, especially in endemic areas of West Africa.

RCTs are needed to investigate the role of corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents when malarial nephropathy progresses, despite eradication of the malarial parasite.

DISCLAIMER

While every effort is made by the publishers, editorial board, and ISN to see that no inaccurate or misleading data, opinion or statement appears in this Journal, they wish to make it clear that the data and opinions appearing in the articles and advertisements herein are the responsibility of the contributor, copyright holder, or advertiser concerned. Accordingly, the publishers and the ISN, the editorial board and their respective employers, office and agents accept no liability whatsoever for the consequences of any such inaccurate or misleading data, opinion or statement. While every effort is made to ensure that drug doses and other quantities are presented accurately, readers are advised that new methods and techniques involving drug usage, and described within this Journal, should only be followed in conjunction with the drug manufacturer's own published literature.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary Table 42: Summary table of studies examining prednisone or CsA treatment vs. control in patients with schistosoma and nephropathy (categorical outcomes).

Supplementary Table 43: Summary table of studies examining prednisone or CsA treatment vs. control in patients with schistosoma and nephropathy (continuous outcomes).

Supplementary material is linked to the online version of the paper at http://www.kdigo.org/clinical_practice_guidelines/GN.php

References

- Genovese G, Friedman DJ, Ross MD, et al. Association of trypanolytic ApoL1 variants with kidney disease in African Americans. Science. 2010;329:841–845. doi: 10.1126/science.1193032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montseny JJ, Meyrier A, Kleinknecht D, et al. The current spectrum of infectious glomerulonephritis. Experience with 76 patients and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1995;74:63–73. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199503000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroni G, Pozzi C, Quaglini S, et al. Long-term prognosis of diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis associated with infection in adults. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:1204–1211. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.7.1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasr SH, Markowitz GS, Stokes MB, et al. Acute postinfectious glomerulonephritis in the modern era: experience with 86 adults and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2008;87:21–32. doi: 10.1097/md.0b013e318161b0fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroni G, Ponticelli C.Acute post-infectious glomerulonephritisIn: Ponticelli C, Glassock R (eds).Treatment of Primary Glomerulonephritis2nd edn.Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; 2009153–177. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Iturbe B, Musser JM. The current state of poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:1855–1864. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008010092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batsford SR, Mezzano S, Mihatsch M, et al. Is the nephritogenic antigen in post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis pyrogenic exotoxin B (SPE B) or GAPDH. Kidney Int. 2005;68:1120–1129. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizawa N, Yamakami K, Fujino M, et al. Nephritis-associated plasmin receptor and acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis: characterization of the antigen and associated immune response. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:1785–1793. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000130624.94920.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin DS. Poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis. A progressive disease. Am J Med. 1977;62:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(77)90344-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habib G, Hoen B, Tornos P, et al. Guidelines on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of infective endocarditis (new version 2009): the Task Force on the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) and the International Society of Chemotherapy (ISC) for Infection and Cancer. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2369–2413. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoen B, Alla F, Selton-Suty C, et al. Changing profile of infective endocarditis: results of a 1-year survey in France. JAMA. 2002;288:75–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koya D, Shibuya K, Kikkawa R, et al. Successful recovery of infective endocarditis-induced rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis by steroid therapy combined with antibiotics: a case report. BMC Nephrol. 2004;5:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-5-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata Y, Ohta S, Kawai K, et al. Shunt nephritis with positive titers for ANCA specific for proteinase 3. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:e11–e16. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of hepatitis C in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2008. pp. S1–S99. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Alter MJ. Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2436–2441. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i17.2436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poynard T, Yuen MF, Ratziu V, et al. Viral hepatitis C. Lancet. 2003;362:2095–2100. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)15109-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams R. Global challenges in liver disease. Hepatology. 2006;44:521–526. doi: 10.1002/hep.21347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perico N, Cattaneo D, Bikbov B, et al. Hepatitis C infection and chronic renal diseases. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:207–220. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03710708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RJ, Gretch DR, Yamabe H, et al. Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis associated with hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:465–470. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199302183280703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers CM, Seeff LB, Stehman-Breen CO, et al. Hepatitis C and renal disease: an update. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42:631–657. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00828-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roccatello D, Fornasieri A, Giachino O, et al. Multicenter study on hepatitis C virus-related cryoglobulinemic glomerulonephritis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;49:69–82. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico G. Renal involvement in hepatitis C infection: cryoglobulinemic glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 1998;54:650–671. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arase Y, Ikeda K, Murashima N, et al. Glomerulonephritis in autopsy cases with hepatitis C virus infection. Intern Med. 1998;37:836–840. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.37.836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamar N, Izopet J, Alric L, et al. Hepatitis C virus-related kidney disease: an overview. Clin Nephrol. 2008;69:149–160. doi: 10.5414/cnp69149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz GS, Cheng JT, Colvin RB, et al. Hepatitis C viral infection is associated with fibrillary glomerulonephritis and immunotactoid glomerulopathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9:2244–2252. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V9122244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabry A, A EA, Sheashaa H, et al. HCV associated glomerulopathy in Egyptian patients: clinicopathological analysis. Virology. 2005;334:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghany MG, Strader DB, Thomas DL, et al. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C: an update. Hepatology. 2009;49:1335–1374. doi: 10.1002/hep.22759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:975–982. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadziyannis SJ, Sette H, Jr, Morgan TR, et al. Peginterferon-alpha2a and ribavirin combination therapy in chronic hepatitis C: a randomized study of treatment duration and ribavirin dose. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:346–355. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-5-200403020-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358:958–965. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)06102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RJ, Gretch DR, Couser WG, et al. Hepatitis C virus-associated glomerulonephritis. Effect of alpha-interferon therapy. Kidney Int. 1994;46:1700–1704. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misiani R, Bellavita P, Fenili D, et al. Interferon alfa-2a therapy in cryoglobulinemia associated with hepatitis C virus. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:751–756. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199403173301104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cresta P, Musset L, Cacoub P, et al. Response to interferon alpha treatment and disappearance of cryoglobulinaemia in patients infected by hepatitis C virus. Gut. 1999;45:122–128. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.1.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsuda A, Imai H, Wakui H, et al. Clinicopathological analysis and therapy in hepatitis C virus-associated nephropathy. Intern Med. 1996;35:529–533. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.35.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzaro C, Panarello G, Carniello S, et al. Interferon versus steroids in patients with hepatitis C virus-associated cryoglobulinaemic glomerulonephritis. Dig Liver Dis. 2000;32:708–715. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(00)80335-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cid MC, Hernandez-Rodriguez J, Robert J, et al. Interferon-alpha may exacerbate cryoblobulinemia-related ischemic manifestations: an adverse effect potentially related to its anti-angiogenic activity. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1051–1055. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199905)42:5<1051::AID-ANR26>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Yonemura K, Miyaji T, et al. Progressive renal failure and blindness due to retinal hemorrhage after interferon therapy for hepatitis C virus-associated membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. Intern Med. 2001;40:708–712. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.40.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garini G, Allegri L, Lannuzzella F, et al. HCV-related cryoglobulinemic glomerulonephritis: implications of antiviral and immunosuppressive therapies. Acta Biomed. 2007;78:51–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruchfeld A, Lindahl K, Stahle L, et al. Interferon and ribavirin treatment in patients with hepatitis C-associated renal disease and renal insufficiency. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18:1573–1580. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garini G, Allegri L, Carnevali L, et al. Interferon-alpha in combination with ribavirin as initial treatment for hepatitis C virus-associated cryoglobulinemic membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;38:E35. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2001.29291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi P, Bertani T, Baio P, et al. Hepatitis C virus-related cryoglobulinemic glomerulonephritis: long-term remission after antiviral therapy. Kidney Int. 2003;63:2236–2241. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabry AA, Sobh MA, Sheaashaa HA, et al. Effect of combination therapy (ribavirin and interferon) in HCV-related glomerulopathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:1924–1930. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.11.1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alric L, Plaisier E, Thebault S, et al. Influence of antiviral therapy in hepatitis C virus-associated cryoglobulinemic MPGN. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:617–623. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2003.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacoub P, Saadoun D, Limal N, et al. PEGylated interferon alfa-2b and ribavirin treatment in patients with hepatitis C virus-related systemic vasculitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:911–915. doi: 10.1002/art.20958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzaro C, Zorat F, Caizzi M, et al. Treatment with peg-interferon alfa-2b and ribavirin of hepatitis C virus-associated mixed cryoglobulinemia: a pilot study. J Hepatol. 2005;42:632–638. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saadoun D, Resche-Rigon M, Thibault V, et al. Antiviral therapy for hepatitis C virus--associated mixed cryoglobulinemia vasculitis: a long-term followup study. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:3696–3706. doi: 10.1002/art.22168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrizi F, Bruchfeld A, Mangano S, et al. Interferon therapy for HCV-associated glomerulonephritis: meta-analysis of controlled trials. Int J Artif Organs. 2007;30:212–219. doi: 10.1177/039139880703000306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles ED, Dustin LB. Hepatitis C virus-induced cryoglobulinemia. Kidney Int. 2009;76:818–824. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koziolek MJ, Scheel A, Bramlage C, et al. Effective treatment of hepatitis C-associated immune-complex nephritis with cryoprecipitate apheresis and antiviral therapy. Clin Nephrol. 2007;67:245–249. doi: 10.5414/cnp67245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed MS, Wong CF. Should rituximab be the rescue therapy for refractory mixed cryoglobulinemia associated with hepatitis C. J Nephrol. 2007;20:350–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacoub P, Delluc A, Saadoun D, et al. Anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (rituximab) treatment for cryoglobulinemic vasculitis: where do we stand. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:283–287. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.065565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansonno D, De Re V, Lauletta G, et al. Monoclonal antibody treatment of mixed cryoglobulinemia resistant to interferon alpha with an anti-CD20. Blood. 2003;101:3818–3826. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saadoun D, Resche-Rigon M, Sene D, et al. Rituximab combined with Peg-interferon-ribavirin in refractory hepatitis C virus-associated cryoglobulinaemia vasculitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1431–1436. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.081653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garini G, Allegri L, Carnevali ML, et al. Successful treatment of severe/active cryoglobulinaemic membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis associated with hepatitis C virus infection by means of the sequential administration of immunosuppressive and antiviral agents. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:3333–3334. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannuzzella F, Vaglio A, Garini G. Management of hepatitis C virus-related mixed cryoglobulinemia. Am J Med. 2010;123:400–408. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saadoun D, Resche Rigon M, Sene D, et al. Rituximab plus Peg-interferon-alpha/ribavirin compared with Peg-interferon-alpha/ribavirin in hepatitis C-related mixed cryoglobulinemia Blood 2010116326–334.quiz 504–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Association For The Study Of The Liver EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2009;50:227–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorrell MF, Belongia EA, Costa J, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: management of hepatitis B. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:104–110. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-2-200901200-00100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen SK, Brown RS., Jr Hepatitis B treatment: Lessons for the nephrologist. Kidney Int. 2006;70:1897–1904. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appel G. Viral infections and the kidney: HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C. Cleve Clin J Med. 2007;74:353–360. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.74.5.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology. 2009;50:661–662. doi: 10.1002/hep.23190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepkowitz KA. One disease, two epidemics--AIDS at 25. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2411–2414. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel PL, Barisoni L, Kopp JB. Pathogenesis and treatment of HIV-associated renal diseases: lessons from clinical and animal studies, molecular pathologic correlations, and genetic investigations. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:214–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt CM, Klotman PE. HIV-1 and HIV-associated nephropathy 25 years later. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2 (Suppl 1:S20–S24. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03561006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genovese G, Tonna SJ, Knob AU, et al. A risk allele for focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in African Americans is located within a region containing APOL1 and MYH9. Kidney Int. 2010;78:698–704. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SD, Kimmel PL. Immune complex renal disease and human immunodeficiency virus infection. Semin Nephrol. 2008;28:535–544. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szczech LA, Gupta SK, Habash R, et al. The clinical epidemiology and course of the spectrum of renal diseases associated with HIV infection. Kidney Int. 2004;66:1145–1152. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szczech LA, Hoover DR, Feldman JG, et al. Association between renal disease and outcomes among HIV-infected women receiving or not receiving antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:1199–1206. doi: 10.1086/424013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sadr WM, Lundgren JD, Neaton JD, et al. CD4+ count-guided interruption of antiretroviral treatment. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2283–2296. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalayjian RC, Franceschini N, Gupta SK, et al. Suppression of HIV-1 replication by antiretroviral therapy improves renal function in persons with low CD4 cell counts and chronic kidney disease. AIDS. 2008;22:481–487. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f4706d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krawczyk CS, Holmberg SD, Moorman AC, et al. Factors associated with chronic renal failure in HIV-infected ambulatory patients. AIDS. 2004;18:2171–2178. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200411050-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters PJ, Moore DM, Mermin J, et al. Antiretroviral therapy improves renal function among HIV-infected Ugandans. Kidney Int. 2008;74:925–929. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid A, Stohr W, Walker AS, et al. Severe renal dysfunction and risk factors associated with renal impairment in HIV-infected adults in Africa initiating antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1271–1281. doi: 10.1086/533468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta SK, Parker RA, Robbins GK, et al. The effects of highly active antiretroviral therapy on albuminuria in HIV-infected persons: results from a randomized trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:2237–2242. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfi053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta SK, Smurzynski M, Franceschini N, et al. The effects of HIV type-1 viral suppression and non-viral factors on quantitative proteinuria in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era. Antivir Ther. 2009;14:543–549. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longenecker CT, Scherzer R, Bacchetti P, et al. HIV viremia and changes in kidney function. AIDS. 2009;23:1089–1096. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832a3f24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt CM, Morgello S, Katz-Malamed R, et al. The spectrum of kidney disease in patients with AIDS in the era of antiretroviral therapy. Kidney Int. 2009;75:428–434. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt CM, Winston JA, Malvestutto CD, et al. Chronic kidney disease in HIV infection: an urban epidemic. AIDS. 2007;21:2101–2103. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282ef1bb4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas M, Kaul S, Eustace JA. HIV-associated immune complex glomerulonephritis with ″lupus-like″ features: a clinicopathologic study of 14 cases. Kidney Int. 2005;67:1381–1390. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine DM, Perazella MA, Lucas GM, et al. Kidney biopsy in HIV: beyond HIV-associated nephropathy. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;51:504–514. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerntholtz TE, Goetsch SJ, Katz I. HIV-related nephropathy: a South African perspective. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1885–1891. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han TM, Naicker S, Ramdial PK, et al. A cross-sectional study of HIV-seropositive patients with varying degrees of proteinuria in South Africa. Kidney Int. 2006;69:2243–2250. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SD, Kimmel PL. Renal biopsy is necessary for the diagnosis of HIV-associated renal diseases. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2009;5:22–23. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babut-Gay ML, Echard M, Kleinknecht D, et al. Zidovudine and nephropathy with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:856–857. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-111-10-856_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ifudu O, Rao TK, Tan CC, et al. Zidovudine is beneficial in human immunodeficiency virus associated nephropathy. Am J Nephrol. 1995;15:217–221. doi: 10.1159/000168835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner JT.Resolution of renal failure after initiation of HAART: 3 cases and a discussion of the literature AIDS Read 200212103–105., 110-102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szczech LA, Edwards LJ, Sanders LL, et al. Protease inhibitors are associated with a slowed progression of HIV-related renal diseases. Clin Nephrol. 2002;57:336–341. doi: 10.5414/cnp57336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas GM, Eustace JA, Sozio S, et al. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and the incidence of HIV-1-associated nephropathy: a 12-year cohort study. AIDS. 2004;18:541–546. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200402200-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atta MG, Gallant JE, Rahman MH, et al. Antiretroviral therapy in the treatment of HIV-associated nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:2809–2813. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalayjian RC. The treatment of HIV-associated nephropathy. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2010;17:59–71. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2009.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eustace JA, Nuermberger E, Choi M, et al. Cohort study of the treatment of severe HIV-associated nephropathy with corticosteroids. Kidney Int. 2000;58:1253–1260. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laradi A, Mallet A, Beaufils H, et al. HIV-associated nephropathy: outcome and prognosis factors. Groupe d' Etudes Nephrologiques d'Ile de France. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9:2327–2335. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V9122327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MC, Austen JL, Carey JT, et al. Prednisone improves renal function and proteinuria in human immunodeficiency virus-associated nephropathy. Am J Med. 1996;101:41–48. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(96)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingulli E, Tejani A, Fikrig S, et al. Nephrotic syndrome associated with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in children. J Pediatr. 1991;119:710–716. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80284-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yahaya I, Uthman AO, Uthman MM.Interventions for HIV-associated nephropathy Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009. CD007183. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Elewa U, Sandri AM, Rizza SA, et al. Treatment of HIV-associated nephropathies. Nephron Clin Pract. 2011;118:c346–c354. doi: 10.1159/000323666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak JE, Szczech LA.(eds.)HIV and kidney disease Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2010171–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitsulo L, Engels D, Montresor A, et al. The global status of schistosomiasis and its control. Acta Trop. 2000;77:41–51. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(00)00122-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chugh KS, Harries AD, Dahniya MH, et al. Urinary schistosomiasis in Maiduguri, north east Nigeria. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1986;80:593–599. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1986.11812073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdurrahman MB, Attah B, Narayana PT. Clinicopathological features of hepatosplenic schistosomiasis in children. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1981;1:5–11. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1981.11748052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Romeh SH, van der Meulen J, Cozma MC, et al. Renal diseases in Kuwait. Experience with 244 renal biopsies. Int Urol Nephrol. 1989;21:25–29. doi: 10.1007/BF02549898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade ZA, Andrade SG, Sadigursky M. Renal changes in patients with hepatosplenic schistosomiasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1971;20:77–83. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1971.20.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra Shekhar K, Pathmanathan R. Schistosomiasis in Malaysia. Rev Infect Dis. 1987;9:1026–1037. doi: 10.1093/clinids/9.5.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcao HA, Gould DB. Immune complex nephropathy i schistosomiasis. Ann Intern Med. 1975;83:148–154. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-83-2-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musa AM, Asha HA, Veress B. Nephrotic syndrome in Sudanese patients with schistosomiasis mansoni infection. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1980;74:615–618. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1980.11687394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queiroz PF, Brito E, Martinelli R, et al. Nephrotic syndrome in patients with Schistosoma mansoni infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1973;22:622–628. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1973.22.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha H, Cruz T, Brito E, et al. Renal involvement in patients with hepatosplenic Schistosomiasis mansoni. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1976;25:108–115. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1976.25.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobh MA, Moustafa FE, el-Housseini F, et al. Schistosomal specific nephropathy leading to end-stage renal failure. Kidney Int. 1987;31:1006–1011. doi: 10.1038/ki.1987.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsoum RS. Schistosomal glomerulopathies. Kidney Int. 1993;44:1–12. doi: 10.1038/ki.1993.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsoum RS, Abdel-Rahman AY, Francis MR, et al. Patterns of glomerular injury associated with hepato-splenic schistosomiasis. Proceedings of the XII Egyptian Congress of Nephrology. Cairo, Egypt. 1992.

- Sobh M, Moustafa F, el-Arbagy A, et al. Nephropathy in asymptomatic patients with active Schistosoma mansoni infection. Int Urol Nephrol. 1990;22:37–43. doi: 10.1007/BF02550434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabello AL, Lambertucci JR, Freire MH, et al. Evaluation of proteinuria in an area of Brazil endemic for schistosomiasis using a single urine sample. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1993;87:187–189. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(93)90485-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eltoum IA, Ghalib HW, Sualaiman S, et al. Significance of eosinophiluria in urinary schistosomiasis. A study using Hansel's stain and electron microscopy. Am J Clin Pathol. 1989;92:329–338. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/92.3.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinelli R, Pereira LJ, Brito E, et al. Renal involvement in prolonged Salmonella bacteremia: the role of schistosomal glomerulopathy. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1992;34:193–198. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46651992000300002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassily S, Farid Z, Barsoum RS, et al. Renal biopsy in Schistosoma-Salmonella associated nephrotic syndrome. J Trop Med Hyg. 1976;79:256–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambertucci JR, Godoy P, Neves J, et al. Glomerulonephritis in Salmonella-Schistosoma mansoni association. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1988;38:97–102. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1988.38.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross AG, Bartley PB, Sleigh AC, et al. Schistosomiasis. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1212–1220. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra012396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinelli R, Pereira LJ, Brito E, et al. Clinical course of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis associated with hepatosplenic schistosomiasis mansoni. Nephron. 1995;69:131–134. doi: 10.1159/000188427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobh MA, Moustafa FE, Sally SM, et al. A prospective, randomized therapeutic trial for schistosomal specific nephropathy. Kidney Int. 1989;36:904–907. doi: 10.1038/ki.1989.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdul-Fattah MM, Yossef SM, Ebraheem ME, et al. Schistosomal glomerulopathy: a putative role for commonly associated Salmonella infection. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 1995;25:165–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinelli R, Pereira LJ, Rocha H. The influence of anti-parasitic therapy on the course of the glomerulopathy associated with Schistosomiasis mansoni. Clin Nephrol. 1987;27:229–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobh MA, Moustafa FE, Sally SM, et al. Characterisation of kidney lesions in early schistosomal-specific nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1988;3:392–398. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.ndt.a091686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussenzveig I, De Brito T, Carneiro CR, et al. Human Schistosoma mansoni-associated glomerulopathy in Brazil. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:4–7. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bariety J, Barbier M, Laigre MC, et al. [Proteinuria and loaiasis. Histologic, optic and electronic study of a case] Bull Mem Soc Med Hop Paris. 1967;118:1015–1025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chugh KS, Singhal PC, Tewari SC, et al. Acute glomerulonephritis associated with filariasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1978;27:630–631. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1978.27.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Date A, Gunasekaran V, Kirubakaran MG, et al. Acute eosinophilic glomerulonephritis with Bancroftian filariasis. Postgrad Med J. 1979;55:905–907. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.55.650.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngu JL, Chatelanat F, Leke R, et al. Nephropathy in Cameroon: evidence for filarial derived immune-complex pathogenesis in some cases. Clin Nephrol. 1985;24:128–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillay VK, Kirch E, Kurtzman NA. Glomerulopathy associated with filarial loiasis. JAMA. 1973;225:179. doi: 10.1001/jama.1973.03220290057028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakasa NM, Nseka NM, Nyimi LM. Secondary collapsing glomerulopathy associated with Loa loa filariasis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;30:836–839. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(97)90090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormerod AD, Petersen J, Hussey JK, et al. Immune complex glomerulonephritis and chronic anaerobic urinary infection--complications of filariasis. Postgrad Med J. 1983;59:730–733. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.59.697.730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall CL, Stephens L, Peat D, et al. Nephrotic syndrome due to loiasis following a tropical adventure holiday: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Nephrol. 2001;56:247–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyer G, Ottesen EA, Galdino E, et al. Renal abnormalities in microfilaremic patients with Bancroftian filariasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;46:745–751. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.46.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhammer J, Birk HW, Zahner H. Renal disease in lymphatic filariasis: evidence for tubular and glomerular disorders at various stages of the infection. Trop Med Int Health. 1997;2:875–884. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1997.d01-404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruel T, Arborio M, Schill H, et al. [Nephropathy and filariasis from Loa loa. Apropos of 1 case of adverse reaction to a dose of ivermectin] Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1997;90:179–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngu JL, Adam M, Leke R, et al. Proteinuria associated with diethylcarbamazine treatment of onchocerciasis (abstract) Lancet. 1980;315:710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abel L, Ioly V, Jeni P, et al. Apheresis in the management of loiasis with high microfilariaemia and renal disease. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986;292:24. doi: 10.1136/bmj.292.6512.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsoum RS. Malarial nephropathies. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13:1588–1597. doi: 10.1093/ndt/13.6.1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiam-Ong S. Malarial nephropathy. Semin Nephrol. 2003;23:21–33. doi: 10.1053/snep.2003.50002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olowu WA, Adelusola KA, Adefehinti O, et al. Quartan malaria-associated childhood nephrotic syndrome: now a rare clinical entity in malaria endemic Nigeria. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:794–801. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doe JY, Funk M, Mengel M, et al. Nephrotic syndrome in African children: lack of evidence for ‘tropical nephrotic syndrome'. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:672–676. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfi297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seggie J, Davies PG, Ninin D, et al. Patterns of glomerulonephritis in Zimbabwe: survey of disease characterised by nephrotic proteinuria. Q J Med. 1984;53:109–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]