Abstract

Stem cells are defined as precursor cells that have the capacity to self-renew and to generate multiple mature cell types. Only after collecting and culturing tissues is it possible to classify cells according to this operational concept. This difficulty in identifying stem cells in situ, without any manipulation, limits the understanding of their true nature. This review aims at presenting, to health professionals interested in this area, an overview on the biology of embryonic and adult stem cells, and their therapeutic potential.

Keywords: adult stem cells, biological characteristics, cell therapy, embryonic stem cells, human diseases

Although the initial concept of stem cells is more than 100 years old,1 and much of its biology and therapeutic potential has been explored in the past three decades, we still know little about their true nature. This review is intended to provide an overview on the biology of stem cells and their therapeutic potential to those interested in this field.

Stem cells are operationally defined as cells that have the potential for unlimited or prolonged self-renewal, as well as the ability to give rise to at least one type of mature, differentiated cells.2, 3 Although this basic definition of ‘stemness' applies generally to stem cells, it is necessary to individually consider embryonic and adult stem cells as they do not share much more than the name and the basic definition above.

EMBRYONIC STEM CELLS

In humans, the embryo is defined as the organism from the time of implantation in the uterus until the end of the second month of gestation. Embryonic stem cells (ESCs), however, refer to a much more restricted period, resulting from the isolation and cultivation of cells from the blastocyst, which forms at approximately 5 days after fertilization.4

Establishing ESC lines

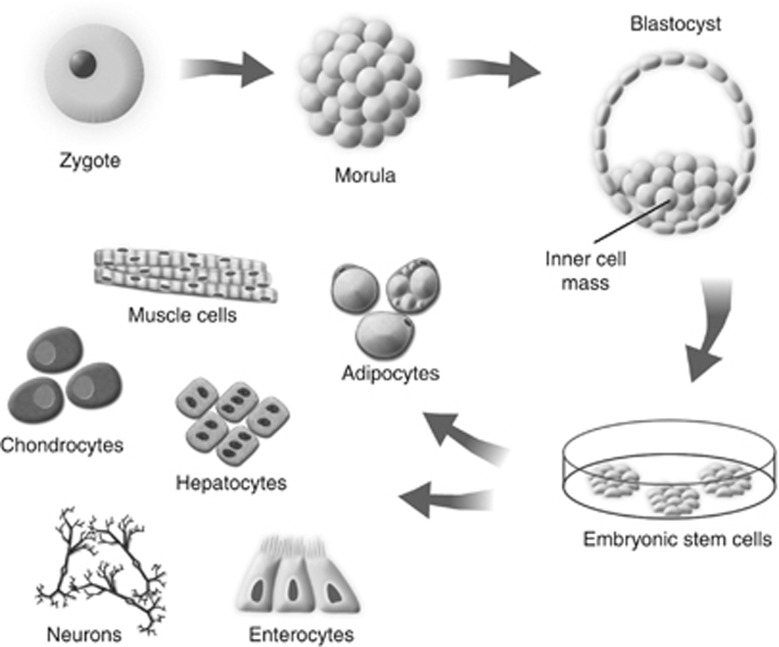

The zygote, which is the cell resulting from the fertilization of an oocyte by a spermatozoon, is totipotent. Several successive cell divisions generate the morula, with 32–64 totipotent cells. After that stage, it develops into the blastocyst, which consists of a hollow ball of cells. Peripheral cells (the trophoblast) of the blastocyst generate the embryonic membranes and placenta, whereas the inner cell mass develops into the fetus. These are the cells that are used to establish stem cell cultures (Figure 1). They are not totipotent, as they do not have the ability to support the formation of another embryo, and are considered to be pluripotent as they can produce all the cell types of the adult organism. Further development of the embryo leads to the formation of the gastrula, composed of the three germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm), from which the complete organism develops.

Figure 1.

Embryonic stem cell cultivation. The zygote undergoes successive mitotic divisions until a sphere of cells—the blastocyst—is formed. In the blastocyst, the trophoblast at its periphery generates the embryonic membranes and placenta, whereas the inner cell mass develops into the fetus. Embryonic stem cells are immortal in culture, having been established from one pluripotent cell collected from the inner cell mass. These are capable of differentiating into any of the mature cell types present in the adult organism.

In 1981, two groups established the first ESC lines from mouse blastocysts, and in 1998 the first human ESC line was generated.5 Although seemingly simple, the procedure is technically demanding because of the need for strictly controlled conditions necessary for the maintenance of the cells in the undifferentiated state. This is particularly important for human ESCs.6 Once established, ESC lines may be maintained in permanent culture, frozen and thawed, and transported between laboratories. It is estimated that there are currently around 250 human ESC lines in the world, widely shared among different groups. The process of establishing an ESC line requires, however, the destruction of the blastocyst, raising ethical issues as scientific investigation alone is not capable of determining whether blastocysts constitute human beings. An alternative method involves the production of ESCs by collection of only one cell from the inner cell mass, allowing implantation of the remaining cells in the womb. However, ethical considerations still remain as it has to be tested whether the remaining cells can develop into a normal human being.

Characteristics of ESCs

Cultured ESCs show defined characteristics: they are pluripotent, capable of differentiating into cells derived from all three germ layers; they are immortal in culture and may be maintained for several hundred passages in the undifferentiated state; and they maintain a normal chromosomal composition.

Molecular characterization of ESCs is well developed, and they are known to express surface markers such as CD9, CD24, and alkaline phosphatase, and several genes involved with pluripotency, including Oct-4, Rex-1, SOX-2, Nanog, LIN28, Thy-1, and SSEA-3 and -4.7 Expression of high levels of telomerase explains their immortality in culture.

ESC research focuses mainly on two issues, both of which have shown significant progress in the past few years.6 The first point explores how to better maintain the cells in long-term culture, without significant modifications of their genetic composition and, in the case of human ESCs, avoiding the need for animal products in the culture. Generally, the cells are maintained in culture on feeder cells such as mouse fibroblasts. The second point focuses on how to differentiate the cells into the many mature cell types that are necessary for the potential treatment of different diseases. ESCs can be induced to differentiate into various cell types in suspension culture, resulting in three-dimensional cell aggregates called embryoid bodies. This tendency of ESCs to differentiate spontaneously may not always be desirable. A technical challenge is to control the differentiation process: although the addition of growth factors directs the differentiation process, usually the cultures spontaneously differentiate into various cell types. It is thus necessary to use methods that allow removal of undifferentiated ESCs from cultures in which the differentiated cell types are the desired product.

Induced pluripotent stem cells

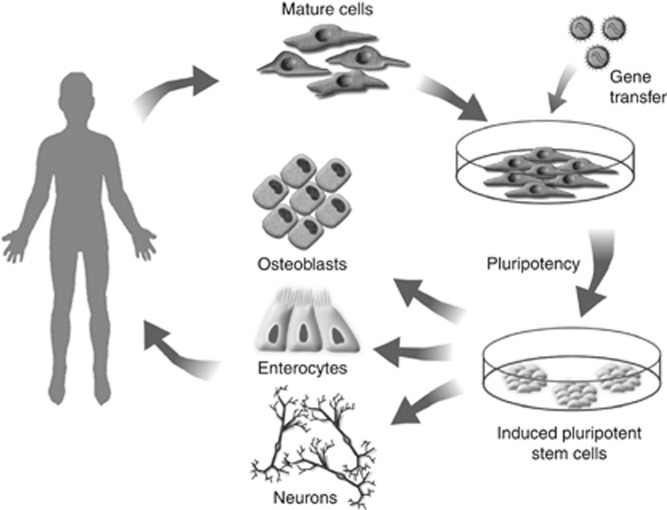

Recently, methods for direct reprogramming of adult cells to induced pluripotent stem cells have been developed.8 In the process, mature cells from the patient are treated in vitro with genes that ‘dedifferentiate' them to a pluripotent stage, similar to an ESC (Figure 2). Induced pluripotent stem cells are believed to be identical to natural pluripotent ESCs in many respects, including the expression of specific genes and proteins, chromatin methylation patterns, culture kinetics, in vitro differentiation patterns, and teratoma formation. Besides avoiding the ethical issues associated with the destruction of human embryos, this approach allows the generation of patient-specific cells of any lineage. Problems related to the genetic modification of target cells, however, must still be resolved before induced pluripotent stem cells may be clinically tested.

Figure 2.

Production of induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells. iPS cells are produced by treating mature cells, such as fibroblasts, with genes that ‘dedifferentiate' them to a pluripotent stage, similar to an embryonic stem cell. Viral vectors, such as retroviruses, are generally used for gene transfer. The transformed cells become morphologically and biochemically similar to pluripotent stem cells, with the advantage of representing autologous cells in therapeutic applications.

Therapeutic potential of ESCs

The principal advantage of ESCs over adult stem cells is related to their pluripotency and limitless expansion in culture, as they have the potential to give rise to all cell types composing the adult organism. This potential is exploited in vitro to develop specialized cells that are then used in therapy.

Owing mainly to safety issues, the clinical use of hESCs is much more restricted than that of adult stem cells. As proof of pluripotency, ESC lineages injected into immunodeficient mice must lead to teratoma formation, with derivatives of all three germ layers. Only differentiated cells derived from ESCs may be administered to patients, as any contaminating undifferentiated cells could give rise to cancer. The first clinical trial using human ESC-derived cells, which in this case are oligodendrocyte progenitor cells, was started in October 2010. Care must be taken, however, to not call this procedure ‘human ESC therapy', as the cells to be used are no longer ESCs.

ADULT STEM CELLS

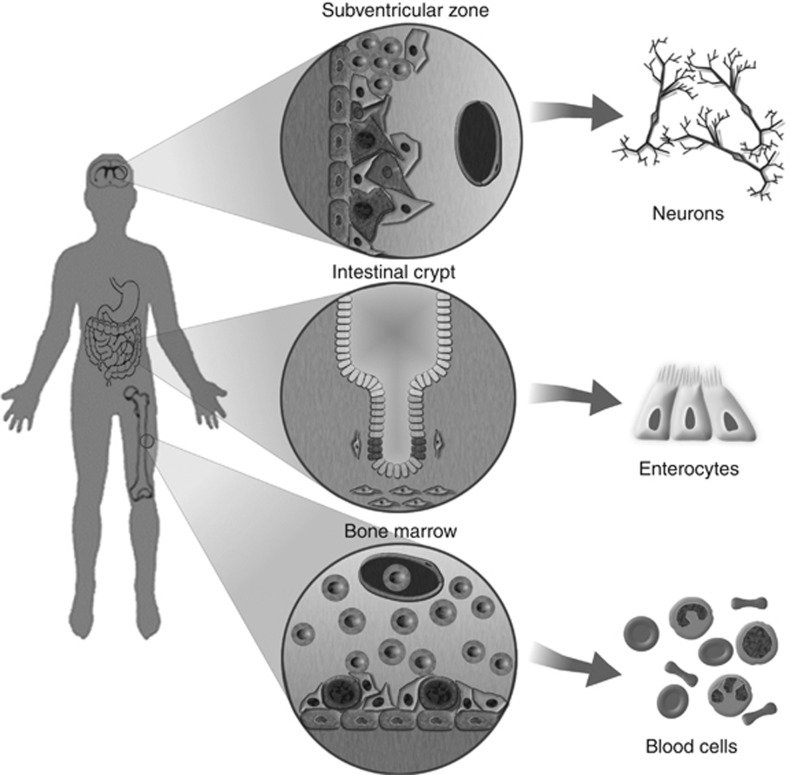

Adult or somatic stem cells (ASCs) are rare, quiescent cells with a more limited self-renewal and differentiation capacity. Numerous types of precursor cells have been isolated in adult tissues, leading to the concept that all tissues have their own compartment of stem cells (Figure 3). They are responsible for replenishing cells that die within a given organ, either due to physiological (wear and tear) or pathological processes.

Figure 3.

Adult or somatic stem cells (ASCs). ASCs are present in all types of organs and tissues in the organism, exemplified here by neuronal stem cells in the subventricular zone of the brain, epithelial stem cells, and hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow. They are responsible for replenishing cells that die, either in physiological (wear and tear) or pathological processes.

Types of adult stem cells

For some of the body compartments, including hematopoietic, epithelial, muscular, and neural, the biological characteristics of their intrinsic stem cells are better defined.9 Hematopoietic stem cells have been in clinical use for more than 40 years, in bone marrow and more recently cord blood transplantation. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are of stromal origin and may be isolated from virtually any tissue in the organism, which suggests a perivascular niche for this population.10, 11 MSCs are attractive for clinical therapy because of their easy in vitro expansion and their ability to differentiate into a variety of tissues, provision of trophic support, and modulation of immune responses.12 Even organs previously considered as post-mitotic, such as the heart or kidney, are now believed to have their own stem cell compartments, which are, however, still poorly understood.13, 14

Adult tissue-specific stem cells are rare and generally do not display characteristic morphology or surface markers that would readily distinguish them from mature cells. They can therefore not be readily ‘isolated' from any given tissue, but a variety of protocols have succeeded to enrich stem/progenitor cells to different degrees of purity. Human hematopoietic stem cells, for instance, are usually collected from the bone marrow or cord blood as CD34- or CD133-positive, CD38- and lineage-negative populations. Even so, the enriched fraction contains other cell types, and hematopoietic stem cells are also present in the cell marker ‘negative' population. The study of ASCs may be classified as basic, when molecular or cellular aspects are investigated; preclinical, when cell therapy protocols are tested in animal models; or as clinical studies, when they are used to treat patients.

Maintenance of adult stem cells in the organism

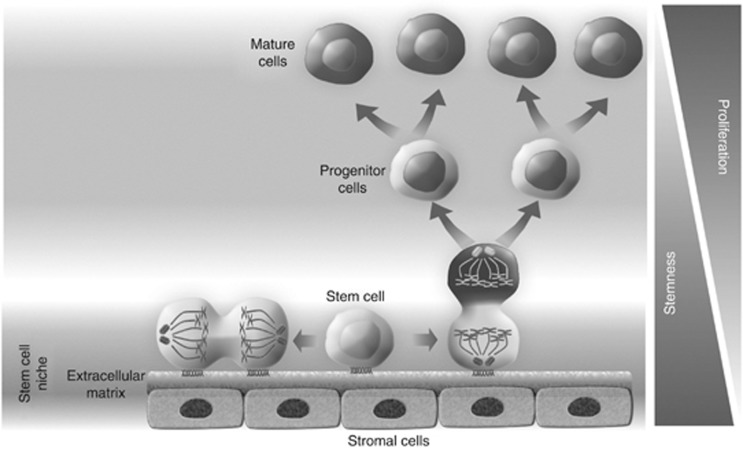

ASCs are capable of long-term self-renewal and of giving rise to mature cell types with specialized functions, reflecting their ability of asymmetric division. Whereas one remains as a self-renewing stem cell, the second daughter cell is committed to replicating and differentiating into a mature cell type (Figure 4). In this case, the cells generated are called precursor or progenitor cells, which, after several rounds of mitosis, give rise to differentiated cells.

Figure 4.

The niche and asymmetric cell division of stem cells. The fate of stem cells is determined by their interaction with their microenvironment or niche. The niche is composed of other (stromal) cells, extracellular matrix (ECM), and signaling factors, which, in combination with intrinsic characteristics of stem cells, define their properties and potential. Adult stem cells divide asymmetrically to produce two kinds of daughter cells. Whereas one remains in the niche as a self-renewing stem cell, the other one becomes a precursor or progenitor cell, exits the niche, and enters a pathway of proliferation and differentiation, which leads to the formation of a mature cell type.

The mechanisms controlling the fate of stem cells are not fully understood, but they strongly depend on the interaction between these cells and their microenvironment or niche. Niches are composed of other cells, extracellular matrix, and signaling factors, which, in combination with intrinsic characteristics of stem cells, define their properties and potential.15 The importance of the niche is becoming increasingly clear, as stemness is maintained only when the cells are attached to it (Figure 4). When ASCs leave the niche, they enter a pathway of proliferation and differentiation.

Only by understanding this relationship and reproducing the niche during in vitro culture willwe be able to expand adult stem cells. The therapeutic use of ASCs also depends on the understanding of this interrelationship, as ACSs must recognize a ‘regenerative niche' at the site of the lesion, home to the sites of tissue injury where they exert their therapeutic activity.

Therapeutic potential of adult stem cells

The plasticity of ASCs is still a controversial issue. Early reports suggesting that tissue-specific stem cells were able to transdifferentiate across lineage boundaries were subsequently shown to be largely due to technical artifacts.16 The question is yet open, but we know that some types of adult stem cells (such as the MSC) have greater plasticity and may therefore represent good candidates for cell therapeutic applications.11

The most obvious and potentially best clinical use of stem cells is to restore (in cell therapy protocols) or replace (in tissue engineering approaches) tissues that have been damaged by disease or injury.17 For example, tissues created using autologous stem cells can be used clinically without induction of an immune response. Moreover, the use of these cells avoids the ethical concerns associated with the use of ESCs. Other problems associated with the clinical use of ESCs, such as spontaneous differentiation with the risk of teratoma formation, are avoided. The potential application of adult stem cells in regenerative medicine is great, as shown in numerous preclinical and clinical studies.

Although hematopoietic stem cells have been used for more than 40 years for hematologic diseases in bone marrow and cord blood transplantation, the therapeutic use of stem cells for non-hematologic disorders has been explored only more recently. A great number of preclinical and clinical studies have been conducted. At the clinical level, however, the number of study subjects in most trials is too small, and controls are often not adequately tested to allow conclusive assessment of the efficacy of such treatments. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of stem cell therapy clinical trials have shown promising results, however, also demonstrating the need for adequately powered and well-controlled trials.18

The most common source from which ASCs are isolated is the bone marrow. The therapeutic results observed for non-hematologic diseases are believed to be due to MSCs, which are also present in this tissue.11 More recently, adipose-derived MSCs have also been used in clinical studies.12 The three major problems with ESCs—ethical issues, immunological rejection problems, and the potential of developing teratomas—are avoided with the use of adult stem cells. Although the true therapeutic potential of stem cells for non-hematologic diseases remains to be determined, the mechanisms responsible for these effects are becoming increasingly understood.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Cientifico e Tecnologico (CNPq) and Fundacao de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul for financial support.

All the authors declared no competing interests.

Footnotes

TO CITE THIS ARTICLE: Chagastelles PC, Nardi NB. Biology of stem cells: an overview. Kidney inter., Suppl. 2011; 1: 63–67.

References

- Ramalho-Santos M, Willenbring H. On the origin of the term ‘stem cell'. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:35–38. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Till JE, McCulloch EA. Hemopoietic stem cell differentiation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1980;605:431–459. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(80)90009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman IL. Stem cells: units of development, units of regeneration, and units in evolution. Cell. 2000;100:157–168. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81692-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards RG. IVF and the history of stem cells. Nature. 2001;413:349–351. doi: 10.1038/35096649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choumerianou DM, Dimitriou H, Kalmanti M. Stem cells: promises versus limitations. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2008;14:53–60. doi: 10.1089/teb.2007.0216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mountford JC. Human embryonic stem cells: origins, characteristics and potential for regenerative therapy. Transfus Med. 2008;18:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3148.2007.00807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rippon HJ, Bishop AE. Embryonic stem cells. Cell Prolif. 2004;37:23–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2004.00298.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maherali N, Hochedlinger K. Guidelines and techniques for the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:595–605. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alison MR, Islam S. Attributes of adult stem cells. J Pathol. 2009;217:144–160. doi: 10.1002/path.2498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Meirelles L, Chagastelles PC, Nardi NB. Mesenchymal stem cells reside in virtually all post-natal organs and tissues. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:2204–2213. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meirelles Lda S, Nardi NB. Methodology, biology and clinical applications of mesenchymal stem cells. Front Biosci. 2009;14:4281–4298. doi: 10.2741/3528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer Nardi N, da Silva Meirelles L. Mesenchymal stem cells: isolation, in vitro expansion and characterization. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2006;174:249–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott HC, Matthiesen TS, Brechtken J, et al. The adult human heart as a source for stem cells: repair strategies with embryonic-like progenitor cells. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2007;4 (Suppl 1:S27–S39. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, Rosenberg ME. Do stem cells exist in the adult kidney. Am J Nephrol. 2008;28:607–613. doi: 10.1159/000117311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs E, Tumbar T, Guasch G. Socializing with the neighbors: stem cells and their niche. Cell. 2004;116:769–778. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00255-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raff M. Adult stem cell plasticity: fact or artifact. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2003;19:1–22. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111301.143037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessina A, Gribaldo L. The key role of adult stem cells: therapeutic perspectives. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22:2287–2300. doi: 10.1185/030079906X148517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Rendon E, Brunskill SJ, Hyde CJ, et al. Autologous bone marrow stem cells to treat acute myocardial infarction: a systematic review. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:1807–1818. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]