Abstract

Saphenous vein graft (SVG) failure is a common finding in patients following coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery. In the literature SVG failure rates have been reported from 25 to over 50% within 10 years. Although common, it remains unclear to what extent SVG failure affects clinical outcome, due to differences in definition, patient selection and follow-up. Particularly the lack of agreement on a universal definition makes comparisons between studies, and therefore generalizability of associations with outcomes, challenging. We suggest using a definition of SVG failure that is based on imaging as well as clinical parameters, that includes reporting SVG failure on both graft and patient level. The use of non-invasive imaging may help improve follow-up rates, and provide a more accurate picture of the real incidence and clinical impact of SVG failure. Given the lack of supportive evidence showing a consistent association between SVG failure and major adverse cardiovascular events, SVG failure should not be considered a valid surrogate endpoint at this time.

Coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery is the criterion standard for treatment of patients with left main disease and multivessel coronary artery disease and those with diabetes.1 The efficacy of surgical revascularization is limited by saphenous vein graft (SVG) failure and progression of coronary artery disease.2 During the first year after CABG, up to 15% of SVGs occlude, and about half of all patients develop SVG failure in >1 graft within 10 years after surgery.3 Early SVG failure is largely due to thrombosis due to graft spasm or technical error.3,4 After the first month, neointimal hyperplasia and later super-imposed atheroma become the driving forces leading to SVG failure.5 Despite the poor patency of SVGs, its ready availability makes it a preferred conduit for circumflex and right coronary artery lesions in approximately 70% of patients undergoing CABG.3 Given that N300,000 patients undergo CABG in the United States each year, the burden of SVG failure on our health care system is therefore one of real concern.6 Despite the high incidence, the relationship between graft failure and subsequent clinical outcomes has not been extensively studied. In this editorial, we will address the challenges involving SVG failure, clinical outcomes, and its use as a surrogate end point in future clinical trials.

Challenges in graft failure research: differences in definitions, failure rates, and selection bias

A universal definition of SVG failure is lacking. The diagnosis of SVG failure could be based on a combination of clinical, angiographic, or other imaging findings in patients with a history of CABG. As such, SVG failure may be interpreted as follows: (a) strict angiographic or imaging diagnosis, (b) angiographic or imaging diagnosis with some evidence of reduced perfusion, (c) angiographic or imaging diagnosis with a clinical event, and (d) clinical event in the early postoperative period. Angiographic or imaging criteria for SVG failure may be interpreted as follows: (a) any narrowing of the lumen of the graft, (b) narrowing of the lumen that functionally limits blood flow as measured for instance by fractional flow reserve, and (c) narrowing of the lumen of N70%. In daily clinical practice, angiography is performed for symptomatic patients with a high suspicion of either coronary or graft disease. In those cases, the diagnosis of SVG failure is based on the finding of a functional stenosis or occlusion of the graft lumen, irrespective of disease in the coronary tree. Therefore, in the clinical setting, SVG failure is mainly an angiographic diagnosis, in which symptoms may or may not be related to graft disease. In an attempt to establish a more systematic approach of assessing SVG patency, FitzGibbon et al7 introduced a grading system in which graft lesions were categorized in grade A, grade B, or grade O in which the proximal and distal anastomoses and bypass trunks were assessed separately, with the final grading the entire graft being the grade for the part rated lowest. Grade A was defined as an excellent graft and run-off. Grade B was defined narrowed to b50% of the caliber of the grafted coronary artery or a new stenosis of the grafted coronary artery N50% of what it was before operation. Grade O was defined as occlusion. To work around the issue of differences in anastomosis configuration, that is, single-outlet, versus branched “Y” type or sequential anastomosed SVGs, each coronary anastomosis is considered to be the distal end of a single bypass graft irrespective of the trunk configuration. Although the FitzGibbon grading system has been used in a number of studies, others have used dichotomous grading system based on a cut-off percentage of stenosis.8 Another definition challenge is patients who died before grafts could be assessed and consent for autopsy was not obtained. In some studies, those patients are accounted for as SVG failure, whereas others do not.9 All these differences in definition have hindered interpretation of data in the literature.

Apart from using various definitions, selection bias is another problem in the presented rates of graft failure among clinical studies. In most clinical studies as well as in clinical practice, SVG failure is based on symptom-based repeat angiography studies. Thus, patients who did not have symptoms or had symptoms but were not subject to angiography, including those deceased, are not accounted for. Other clinical studies assessed graft patency using programmed follow-up either with angiography8 or noninvasive computed tomography10 in all surviving patients irrespective of angina status. Although, ideally, all patients scheduled for programmed assessment would participate, bias also is introduced here because, in reality, a substantial number of patients refuse to undergo follow-up angiography. Those patients are generally more sick and have more comorbidities and are, therefore, also at higher risk for complications during angiography.8 Non-invasive cardiac imaging may, therefore, increase the likelihood of these patients returning for scheduled follow-up. However, compared with angiography, computed tomographic and other imaging techniques are less accurate in assessing patency of nonoccluded grafts and lesions at anastomotic sites and around surgical clips. Overall, reported graft failure rates are usually higher in studies including only symptomatic patients compared with those including all surviving patients.11 Another frequent problem with the published data on failure rates is that studies publish graft failure rates without presenting data “per patient” and/or “per graft.”

Impact of baseline parameters and intraoperative decision making on vein graft failure

Differences in reported graft failure rates can also be attributed to preselection and/or variation in patient and graft characteristics. A number of predictors for vein graft failure have been identified, those include baseline parameters such as age, gender, obesity, diabetes, perioperative drug regimens, but also intraoperative parameters such as on-pump versus off-pump surgery, harvesting technique (open vs endoscopic), handling (no-touch, preservation techniques), harvest site location, vein caliber, target coronary run-off, competitive flow, use of single versus multiple anastomosis, anastomotic technique, and operator experience.11,12

Graft failure and clinical outcomes: results from clinical studies

A limited number of studies have been published on the association of vein graft failure and clinical outcomes. A well-known study from the 1990s by Lytle et al13 compared long-term survival in 2 cohorts: (1) 723 patients with prior CABG who had graft stenosis but did not undergo any revascularization within 12 months of follow-up and (2) 573 patients without documented graft stenosis. After a mean follow-up of 6.9 years, they found that patients with vein graft stenosis occurring within 5 years after surgery and patients with no vein graft stenosis had similar outcomes. However, patients with significant stenosis in SVGs to the left anterior descending coronary artery had higher rates of death and cardiac ischemic events. An analysis from the Duke Cardiovascular Databank reported the clinical impact of early vein graft failure in 1,243 patients who underwent angiography for clinical reasons within 18 months after CABG.14 The investigators also found that vein graft failure was associated with death, myocardial infarction, or revascularization driven by revascularization. Recently, the results of the long-term clinical follow-up study of the PREVENT IV trial9 were published. Saphenous vein graft failure was reported in 43% of patients (787/1,829 patients) and was subsequently associated with an increase in revascularization but not with death and/or myocardial infarction. The authors concluded that although the absolute number of failed grafts did not correlate with long-term clinical outcomes, the proportion of grafts with SVG failure did. A limitation of this analysis was that the trial was not powered for SVG failure and clinical outcome, so modest but significant correlations with outcome could have been missed. Further randomized studies are needed to further evaluate the role of SVG failure on subsequent clinical outcome.

Graft failure as a surrogate end point for clinical studies?

It has been intuitively assumed that (1) graft failure that results in a decrease in blood supply to the supplied myocardium adversely affects recurrence of angina as well as myocardial infarction, subsequent heart failure, and death and (2) clinical outcomes are dependent upon the amount of myocardium involved. Evidence from clinical studies thus far has provided little support of this logic. A number of hurdles must be taken to draw statements on the relationship between graft failure and clinical outcome. First of all, are the factors that affect graft patency the same factors that affect clinical outcome following CABG? For instance, renal failure and diabetes are associated with clinical events after CABG but not with SVG failure, suggesting that outcomes are driven by progression of native coronary disease.15,16 Second, does graft failure directly or indirectly contribute to adverse clinical outcome? And, subsequently do interventions that improve SVG patency also improve clinical outcomes? Third, what are the competing risks for outcomes after CABG, such as progression of cardiovascular atherosclerosis as well as noncardiovascular systemic diseases? Fourth, are coronary vessels subjected for bypass surgery all flow limiting lesions that require intervention? Certainly, in a patient receiving multiple bypass grafts, not all the vein targets are of equal importance. The FAME study that compared fractional flow reserve versus angiography suggests that, in one fifth of all angiographically determined significant coronary lesions (>70% stenosis), there was no evidence of ischemia.17 In such cases, graft failure may likely have little or no clinical consequence. Lastly, it is unclear whether the rate and timing of graft deterioration are of clinical importance. It may be assumed that deterioration of some SVG lesions are of little clinical importance due to competitive flow of the native coronary circulation or because they supply only a small myocardial territory. In others, the need for a patent SVG is only temporarily required until the native coronary vessels developed a sufficient collateral network. In such, acute SVG failure may lead to adverse coronary events, whereas slow-onset SVG failure more remote from CABG may not, as collaterals will take over. Therefore, SVG failure in the early postoperative phase may be of more clinical importance than failure more remote from surgery.

Future directions

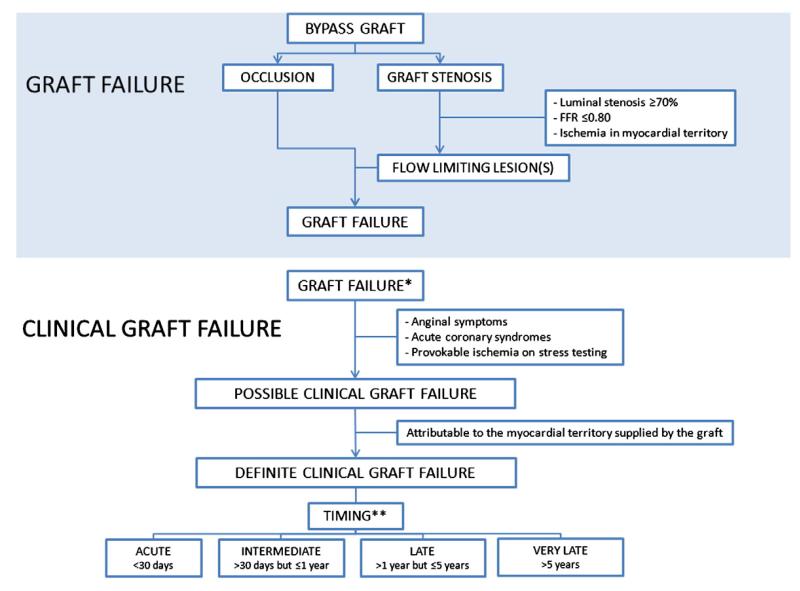

Patients with prior CABG represent a high-risk population for future cardiovascular events. Patient-tailored postoperative medication regimens and lifestyle modification have significant influence on reducing clinical event rates in patients following CABG, irrespective of their effect on sustaining graft patency. Although it remains unclear to what extent graft failure influences clinical outcome, further study is warranted to evaluate surgical techniques18 and medical strategies8 for decreasing SVG failure. An overall consensus for a universal definition is lacking, which makes comparisons between studies as well as generalizability of associations with outcomes challenging. Therefore, a universal definition for graft failure is warranted preferably based on angiographic and/or noninvasive imaging as well as inclusion of clinical variables. In Figure, we present a systematic approach to classify graft failure, in which the definition of bypass graft failure is based on angiographic and/or imaging findings. We also introduce a new term clinical bypass graft failure, which refers to clinical symptoms that are related to the failing graft. In future studies assessing SVG patency, the use of noninvasive imaging methods may help decrease patient drop-out as is seen with angiographic follow-up studies and may help provide a more accurate picture of the clinical impact of SVG failure. Better understanding of factors associated with SVG failure is also required. Further study is needed to provide better insight into whether patients with SVG failure actually have worse subsequent long-term clinical outcomes, and if so, which patients should be monitored more closely. Further implementation of evidence based strategies to improve CABG surgery should be installed, including patient selection, target artery, and graft selection including the use of fractional flow reserve in certain angiographic lesions as well as identification and prevention of factors associated with SVG failure. Given the lack of supportive evidence showing a consistent association between SVG failure and major adverse cardiovascular events, SVG failure should not be considered a valid surrogate end point at this time. In general, new interventions should be shown to improve clinical outcomes and not just imaging based SVG failure.

Figure.

Schematic approach to classify graft failure according to angiographic/imaging criteria as well as clinical graft failure, which takes into account clinical characteristics. *Clinical graft failure can only occur in the presence of documented anatomic or physiologic graft failure and “clinical” as such refers to the finding of graft failure in combination with clinical findings related to the failing graft. **Timing of clinical graft failure can be assessed more accurately than timing of graft failure because of the associated symptoms. For example, a patient who presents with symptoms attributable to graft failure at 2 years after CABG surgery may have had a graft that met the criteria for failure at an earlier stage, but because symptoms attributable to the failing graft did not occur until 2 years after CABG surgery, it is justifiable to call this late clinical graft failure.

Footnotes

Funding sources and disclosures

This manuscript was funded by the Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, NC, and the Academic Medical Center—University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands. The authors are solely responsible for the design and conduct of this study, all study analyses, the drafting and editing of the manuscript, and its final contents.

References

- 1.Kolh P, Wijns W, Danchin N, et al. Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;38:S1–S52. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Motwani JG, Topol EJ. Aortocoronary saphenous vein graft disease. Pathogenesis, predisposition and prevention. Circulation. 1998;97:916–31. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.9.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldman S, Zadina K, Moritz T, et al. for the VA Cooperative Study Group #207/297/36 Long-term patency of saphenous vein and left internal mammary grafts after coronary artery bypass surgery: results from a department of veterans affairs cooperative study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:2149–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.08.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bourassa MG, Campeau L, Lesperance J, et al. Changes in grafts and coronary arteries after saphenous vein aortocoronary bypass surgery: results at repeat angiography. Circulation. 1982;65:90–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.65.7.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murphy GJ, Angelini GD. Insights into the pathogenesis of vein graft disease: lessons from intravascular ultrasound. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2004;2:8. doi: 10.1186/1476-7120-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Epstein AJ, Polsky D, Yang F, et al. Coronary revascularization trends in the United States, 2001-2008. JAMA. 2011;305:1769–76. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.FitzGibbon GM, Burton JR, Leach AJ. Coronary bypass graft fate: angiographic grading of 1400 consecutive grafts early after operation and of 1132 after one year. Circulation. 1978;57:1070–4. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.57.6.1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alexander JH, Hafley G, Harrington RA, et al. Efficacy and safety of edifoligide, an E2F transcription factor decoy, for prevention of vein graft failure following coronary artery bypass graft surgery: PREVENT IV: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294:2446–54. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.19.2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopes RD, Mehta RH, Hafley GE, et al. Project of Ex Vivo Vein Graft Engineering via Transfection IV (PREVENT IV) Investigators. Relationship between vein graft failure and subsequent clinical outcomes after coronary artery bypass surgery. Circulation. 2012;14(125):749–56. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.040311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meyer TS, Martinoff S, Hadamitzky M, et al. Improved noninvasive assessment of coronary artery bypass grafts with 64-slice computed tomographic angiography in an unselected patient population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:946–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buxton BF, Durairaj M, Hare DL, et al. Do angiographic results from symptom-directed studies reflect true graft patency? Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80:896–901. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.03.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopes RD, Hafley GE, Allen KB, et al. Endoscopic versus open vein-graft harvesting in coronary-artery bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:235–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lytle BW, Loop FD, Taylor PC, et al. Vein graft disease: the clinical impact of stenoses in saphenous vein bypass grafts to coronary arteries. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1992;103(5):831–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halabi AR, Alexander JH, Shaw LK, et al. Relation of early saphenous vein graft failure to outcomes following coronary artery bypass surgery. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:1254–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.06.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koshizaka M, Hafley GE, Lopes RD, et al. Diabetic patients have similar vein graft failure at 1 year, but higher 5-year mortality than non-diabetic patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery: insights from the PREVENT-IV trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:E1446. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehta RH, Hafley GE, Gibson CM, et al. Influence of preoperative renal dysfunction on one-year bypass graft patency and two-year outcomes in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;136:1149–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.02.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tonino PA, Fearon WF, DeBruyne B, et al. Angiographic versus functional severity of coronary artery stenoses in the FAME study: Fractional Flow Reserve Versus Angiography in Multivessel Evaluation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2816–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.11.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Souza DS, Johansson B, Bojo L, et al. Harvesting the saphenous vein with surrounding tissue for CABG provides long-term graft patency comparable to the left internal thoracic artery: results of a randomized longitudinal trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;132:373–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]