Abstract

Inhibitor of DNA-binding-1 (ID1) transcription factor is essential for the proliferation and progression of many cancer types including leukemia. However, the ID1 protein has not yet been therapeutically targeted in leukemia. ID1 is normally polyubiquitinated and degraded by the proteasome. Recently, it has been shown that USP1, a ubiquitin specific protease, deubiquitinates ID1 and rescues it from proteasome degradation. Inhibition of USP1 therefore offers a new avenue to target ID1 in cancer. Here, using a Ubiquitin-Rhodamine-based high throughput screening, we identified small molecule inhibitors of USP1 and investigated their therapeutic potential for leukemia. These inhibitors blocked the deubiquitinating enzyme activity of USP1 in vitro in a dose-dependent manner with an IC50 in the high nanomolar range. USP1 inhibitors promoted the degradation of ID1 and, concurrently, inhibited the growth of leukemic cell lines in a dose dependent manner. A known USP1 inhibitor, Pimozide, also promoted ID1 degradation and inhibited growth of leukemic cells. In addition, the growth of primary Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) patient-derived leukemic cells was inhibited by a USP1 inhibitor. Collectively, these results indicate that the novel small molecule inhibitors of USP1 promote ID1 degradation and are cytotoxic to leukemic cells. The identification of USP1 inhibitors therefore opens up a new approach for leukemia therapy.

Keywords: USP1, ID1, small molecule inhibitors, leukemia

INTRODUCTION

ID1 (inhibitor of DNA binding 1) protein is a member of the helix-loop-helix (HLH) family of transcriptional regulatory proteins which consists of four members, ID1-ID4 (1, 2). Basic HLH (bHLH)-family of transcription factors are key regulators of cellular development and differentiation. The bHLH proteins (e.g. E2A, E2-2, HEB) form homodimers or heterodimers with other tissue-specific bHLH proteins (e.g. MyoD, SCL/tal1), bind DNA upon dimerization, and activate transcription of differentiation-associated proteins. The ID-family of HLH proteins can also form dimers with bHLH proteins (3). However, the ID-bHLH heterodimers are transcriptionally inactive and are unable to bind to the DNA since ID proteins lack a basic DNA binding domain (2). Accordingly, ID proteins antagonize the functions of bHLH proteins and inhibit the bHLH protein-mediated transactivation of genes which promote cellular differentiation. ID proteins, therefore, are also termed inhibitors of differentiation. In addition to binding to the bHLH proteins, ID proteins can also interact with non-bHLH proteins and antagonize their function (4).

ID1, one of the ID proteins, is known to play a role in cellular transformation. It is overexpressed in a variety of human cancer types, including pancreatic, cervical, ovarian, prostate, breast, colon and brain cancer (5-11). In most of these cancer types, high ID1 expression correlates with poor prognosis and increased chemoresistance (7, 9, 10, 12, 13). Moreover, functional studies have demonstrated that ID1 can promote cell proliferation, inhibit differentiation, delay cellular senescence in primary human cells, and promote cell migration and the metastatic phenotype of cancers (14). ID1 function is also required for maintaining the ‘stemness” of many normal and malignant tissues (10, 11, 15).

Recent studies indicate that ID1 is also an activator of leukemic cell growth. First, Tang et al (16) observed high levels of ID1 expression in primary AML samples, and high expression correlated with poor prognosis. Second, ID1 was identified as a common downstream target of constitutively activated oncogenic tyrosine kinases, such as BCR-ABL and TEL-ABL(17). Third, ID1 can immortalize hematopoietic progenitors in vitro and promote a myeloproliferative disease in mice in vivo (18). Moreover, knockdown of ID1 expression inhibited leukemic cell growth (18). Collectively, these observations suggest that ID1 is a prime therapeutic target for leukemia and other cancer types. However, suitable drugs to therapeutically target ID1 have not been developed to date (14). Protein-protein interactions in the nucleus, such as the interaction of ID1 with HLH factors, are notoriously difficult to inhibit with small molecules (19).

A recent report offers an alternative strategy for knocking down the ID1 protein-namely, through inhibition of the ubiquitin specific protease, USP1 (20). USP1 is a deubiquitinating (DUB) enzyme, which removes polyubiquitin chains from the ID1 protein (20). ID1 is normally polyubiquitinated and rapidly degraded by the proteasome (21-23). USP1 removes the polyubiquitin chains and rescues ID1 from degradation. Selectively knocking down USP1 using shRNA results in a rapid degradation of ID1 in osteosarcoma cells. Importantly, USP1 knockdown results in decreased mesenchymal cell proliferation, and enhanced differentiation of osteosarcoma cells which overexpress USP1 and ID1 (20), providing a rationale for differentiation therapy of many cancer types including leukemia (e.g. acute myelogenous leukemia (AML), chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML)). We therefore reasoned that pharmacologic inhibition of USP1 would promote ubiquitin-mediated degradation of ID1 protein, resulting in differentiation and growth inhibition of immature leukemic cells. Our laboratory has previously shown that human USP1 forms a stable complex with its binding partner, USP1 associated factor 1 (UAF1) (24). USP1 by itself exhibits low DUB activity; however, this activity is significantly enhanced when bound as a USP1/UAF1 complex. Using high throughput screening, we identified a small molecule inhibitor of the USP1/UAF1 complex. We describe here a novel small molecule (C527), and multiple derivatives, that inhibit USP1 catalytic activity, promote ID1 degradation, and inhibit leukemic cell growth.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

High Throughput Screening

The USP1/UAF1 complex was prepared as described previously (24) (Figure 1) and the protein complex was used for high throughput screening. The fluorogenic ubiquitin-Rhodamine (Ub-Rhodamine) based enzyme assay was established in a 384-well format for high throughput screening. The reaction buffer containing free ubiquitin and USP1/UAF1 enzyme complex was added in 384 well plates using automated liquid handling robot-Bio-Tek Microfill (Bio-Tek Instrments Inc., VT), followed by addition of the compounds (in DMSO) from the compound library plates to wells using a pin transfer robotic system at a final concentration of 10 μM. The reactions were then incubated for 30 min at room temperature followed by the addition of Ub-Rhodamine to initiate the reactions. The enzyme activity of the USP1/UAF1 complex was determined by measuring the fluorescence of Ub-Rhodamine. 150,000 compounds were screened from the library plates at the Partners Center for Drug Discovery, Cambridge, MA. Details of the screen are provided in the ‘supplementary methods” section.

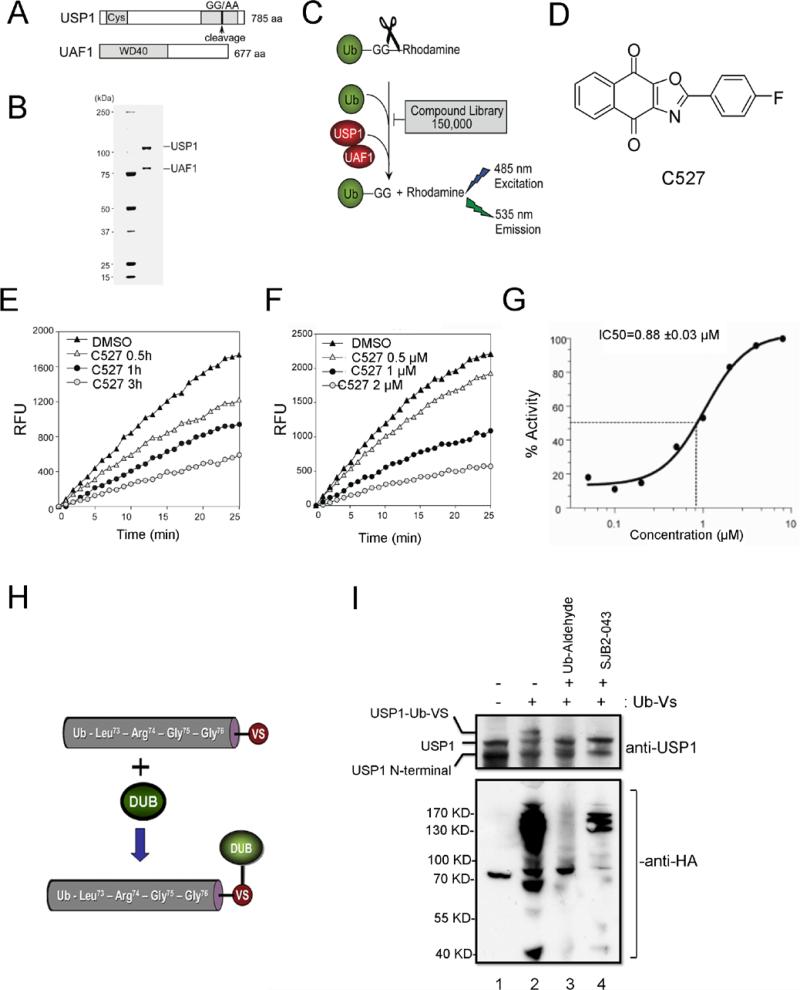

Figure 1. High-throughput screening and identification of USP1/UAF1 inhibitors.

(A) Schematic of the USP1/UAF1 constructs. (B) Coomassie blue staining of the purified USP1/UAF1 complex (C) A schematic of the Ub-Rhodamine based screening assay (D) Chemical structure of a parental USP1 inhibitor compound 527 (C527). (E) C527 inhibits USP1 activity in a time-dependent manner. Purified USP1/UAF1 complex was incubated with 1 μM C527 or DMSO for the indicated time, followed by the addition of Ub-AMC at a 0.5 μM final concentration. Fluorescence (RFU) at 535 nm was measured to indicate the enzymatic activity of USP1. (F) Dose-dependent inhibition of USP1 enzymatic activity by USP1 inhibitor C527. Purified USP1/UAF1 complex was incubated with C527 or DMSO for 3 hrs followed by the addition of Ub-AMC at 0.5 μM concentration. The fluorescence (RFU) at 535 nm was measured to indicate the enzymatic activity of USP1. (G) IC50 plot of C527 against USP/UAF1 complex in an enzymatic reaction, as described in panels E and F. (H,I) USP1 inhibitor SJB2-043 1 μM inhibits the activity of native USP1/UAF1. K562 cells were treated with DMSO or SJB2-043 for 24 hrs and cell extracts were incubated with 0.5 μM Ub-Vs (see structure in panel H) for 45 min. An aliquot of untreated cell extract was treated with Ubiquitin-aldehyde (Ub-Aldehyde, 5 μM) before adding Ub-Vs. The reactions were then subjected to immunoblotting with anti-HA or anti-USP1 antibodies.

In Vitro Deubiquitination Assays

Purified USP5 enzyme was purchased from Boston Biochem. UCH-L1 and UCH-L3 were as reported previously (25). USP12/46 was prepared in our laboratory as described (26, 27). The in vitro enzymatic assays were performed as described previously (24) using ubiquitin-AMC (Ub-7-amido-4methylcoumarin; Boston Biochem) as a substrate in a reaction buffer containing 20 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.8), 20 mM NaCl, 0.1 mg/ml ovalbumin, 0.5 mM EDTA and 10 mM dithiothreitol. The fluorescence was measured by FluoStar Galaxy Fluorometer (BMG Labtech). For the Ub-vinylsulfone (VS) assay, the proteins were incubated with Ub-VS (Boston Biochem) at 0.5 μM final concentration for 45 min at 30 °C, followed by the immunoblotting analysis.

Cells and drug treatments

Leukemic cell lines were grown in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen) and penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen). Hela cells and U2OS cells were grown in DMEM (Invitogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen) and penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen). K562 cells were provided by Dr. Dipanjan Chowdhury (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA). MOLM14 cells were provided by Dr. A. Thomas Look (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA). Luciferase expressing AML cell lines were provided by Dr. Andrew Kung (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA). Mouse osteosarcoma cells were provided by Dr. Stuart Orkin (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA). The cells were provided within the last 24 months. No authentication of the cell lines was done by the authors. USP1 inhibitor C527 and its derivatives were synthesized and the purity was validated by high-performance liquid chromatography. Pimozide was purchased from Sigma. Primary human AML patient samples were collected from DFCI leukemia program under the approval of appropriate protocols. Cells were treated with DMSO or USP1 inhibitors in appropriate medium for 24-72 hrs. The viable cell counts were determined using Trypan blue staining, Cell TiterGlo reagent (Promega) or MTT assay. The apoptotic cells were detected using AnnexinV and 7AAD (BD Biosciences) staining according to the manufacturer's instructions using flow cytometry. For Benzidine staining, the cells were washed twice with PBS and resuspended in 45 μl of PBS + 5 μl of Benzidine stain solution (0.2% in 0.5 M glacial acetic acid, 3% H2O2). After 45 min incubation at room temperature, the Benzidine positive cells were detected by light microscopy.

Antibodies and shRNAs

Western blotting was performed with the following antibodies: anti- USP1 (A301-699A, Bethyl lab), anti- ID1 (B-8, Santa Cruz), anti-Vinculin (H-10, Santa Cruz), anti-alpha tubulin (DM1A, Santa Cruz), anti-ID2 (C-20, Santa Cruz), anti-ID3 (C-20, Santa Cruz), anti-FANCD2 (H-300, Santacruz) and anti-FANCI (28). Doxycyclin-inducible shRNAs in TRIPZ Lentivirus vectors against human USP1 were purchased from Open Biosystems (Thermo Scientific). Mature antisense sequence for the shRNAs were (A)V2THS_171887:TTTATCTTCTCCTACAATC, (B) V2THS_218649: TTAAGATAGCAAGTATTGC and (C) V2THS_171886:TAAACTTTCACATTCCAAG.

Mouse xenograft experiments

6-8 weeks old athymic nude mice were used for xenograft studies. The mouse experiments were reviewed and approved by DFCI's Animal Care and Use Committee. 5 × 106 K562 cells were mixed with matrigel (BD Bioscience) (1:1 ratio) and injected subcutaneously into the flanks of nude mice. When the tumors reached 2 mm3 size, 15 mg/kg Pimozide (dissolved in 2% DMSO+0.3% Tartaric acid) or Vehicle was administered daily. The tumor growth was monitored by measuring the size.

Homologous recombination (HR) analysis and immunofluorescence

HR activity was analyzed by DR-GFP reporter as previously described (29). U2OS-DRGFP cells carrying a chromosomally integrated single copy of HR repair substrate were used. Double strand break (DSB)-induced HR in these cells results in restoration and expression of GFP. Briefly, 24 h after induction of chromosomal DSBs through the expression of I-SceI, U2OS-DRGFP cells were treated with USP1 inhibitor C527 for 24 h. Cells were then subjected to FACS analysis to quantify the percentage of viable GFP-positive cells. The Rad51 foci in cells were detected by immunofluoroscence as described (30) using anti-RAD51 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibodies. The quantification of cells with RAD51 foci was performed by counting the number of cells with RAD51 foci.

RESULTS

Identification of a novel USP1 inhibitor using high throughput screening

We have previously reported that USP1 by itself exhibits poor DUB activity. However, when bound to its interacting partner, UAF1, the catalytic activity of USP1 is significantly enhanced (24). We therefore utilized a purified USP1/UAF1 complex and performed a high throughput screen to identify a USP1 inhibitors (Figure 1). We used the cDNA encoding a full length USP1 polypeptide, which had a substitution of GG to AA at amino acid residues 670 to 671 (Figure 1A). We have previously shown that this amino acid change disrupts an autocleavage site in USP1 but does not alter the interaction of USP1 with UAF1 or the DUB activity of the complex (24, 31). Human USP1 (with GG to AA mutation) and UAF1 proteins were coexpressed in SF9 insect cells to generate a protein complex with elevated DUB activity. The USP1/UAF1 protein complex was purified and the purity was confirmed by coomassie staining (Figure 1B). The stable USP1/UAF1 enzyme complex was then subjected to a high throughput inhibitor screen, described schematically in Figure 1C. A small molecule, C527 (heterocyclic tricyclic 1,4-dihydro-1,4-dioxo-1H-naphthalene) (Figure 1D) was identified which inhibited the USP1/UAF1 complex.

USP1 inhibitor C527 has a high affinity for USP1

We next confirmed the ability of C527 to inhibit the USP1/UAF1 complex in a dose-dependent and time-dependent manner, using Ub-AMC as a substrate (Figure 1E-G). Pretreatment of USP1/UAF1 with C527 resulted in inhibition of its enzyme activity with an IC50 of 0.88 ± 0.03 μM. To determine the specificity of C527 in USP1/UAF1 inhibition, we next examined its ability to inhibit other DUB enzymes in vitro. UAF1 stimulates not only USP1, but also two other DUB enzymes, USP12 and USP46 (26). We therefore tested C527 for its ability to inhibit the purified USP12/USP46 complex or other DUBs. C527 inhibited the DUB activity of the USP12/USP46 complex and other DUB enzymes in vitro. However, the IC50 of C527 for these DUB enzymes was higher in comparison to USP1/UAF1 complex (Table 1). C527 had considerably less inhibitory effect on UCH-L1 and UCH-L3, a different subclass of deubiquitinating enzymes, referred to as the ubiquitin C- terminal hydrolases (25), even though they are also cysteine proteases. Taken together, C527 is a pan-deubiquitinating enzyme inhibitor in vitro, with a high nanomolar IC50 for the USP1/UAF1 complex.

Table 1.

IC50 values of USP1 inhibitor C527 for the indicated deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs).

| DUBs | IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|

| USP1 | 0.88±0.07 |

| USP12/46 | 5.97±0.37 |

| USP5 | 1.65±0.42 |

| UCH-L1 | >10 |

| UCH-L3 | 2.18±0.69 |

In order to generate a USP1 inhibitor with improved cellular potency, we chemically synthesized several analogs/derivatives of C527 and determined their IC50 for USP1/UAF1 inhibition (data not shown). We then selected a derivative, SJB2-043 (IC50=0.544 μM), for further studies due to the feasibility of its large-scale chemical synthesis.

USP1 inhibitor SJB2-043 inhibits the enzyme activity of native USP1

We next determined whether SJB2-043 inhibits the DUB activity of native USP1 complexes isolated from human cells (Figure 1 H, I). For this purpose, we performed competition assays between SJB2-043 and the ubiquitin (Ub) active site probe HA-Ub-Vinyl sulfone (HA-Ub-VS) reagent (Figure 1H). This affinity reagent covalently modifies and traps active DUB enzymes in cell extracts (32). Cells were treated with SJB2-043 for 24 hrs and cell extracts were incubated with HA-Ub-VS, followed by immunoblotting with anti-USP1 or anti-HA antibodies. Consistent with our previous studies and the most recent studies by Piatkov et al (24, 31, 33), USP1 in the untreated cells was detected on western blot as a doublet; full length USP1 and an auto-cleaved USP1 with only N-terminus (Figure 1I, lane 1). The Ub-USP1 conjugates were generated in the untreated cell lysates and were detected by an increase in molecular weight of USP1 (Figure 1I, lane 2). However, the formation of the Ub-USP1 conjugate was inhibited by the addition of SJB2-043 (lanes 4). Ub-aldehyde, a potent known nonspecific DUB inhibitor, caused a complete loss of USP1-Ub-VS conjugates in this competition assay (lane 3). SJB2-043 inhibited the Ub-VS labeling of a limited number of endogenous DUB enzymes (Figure 1I, anti-HA blot). In addition, SJB2-043 inhibited the labeling of USP1 with Ub-VS in a dose dependent manner (supplementary figure 1A). Taken together, these data demonstrate that SJB2-043 is an inhibitor of the native USP1/UAF1 complex.

Novel USP1 inhibitors promote degradation of ID1 in leukemic cells

shRNA knockdown of USP1 results in enhanced proteasome-mediated degradation of ID1 in osteosarcoma cells (20). ID1 degradation in osteosarcoma cells results in mesenchymal differentiation and decreased cell proliferation. We therefore tested whether small molecule USP1 inhibitors enhance ID1 degradation in cells. Indeed, USP1 inhibitor C527 promoted the dose-dependent degradation of ID1 in human U20S osteosarcoma cells (data not shown). We next tested USP1 inhibitors for their ability to inhibit USP1 in various cell lines. The K562 cell line (the erythroleukemia cell line derived from a chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) patient), was treated with SJB2-043 (Figure 2A) for 24 hrs, and USP1 and ID1 protein levels were determined by Western blotting. Interestingly, the SJB2-043 caused a dose-dependent decrease in USP1 levels and a concomitant degradation of ID1 protein in the K562 cells at a micromolar drug concentration (Figure 2B). The decrease in USP1 and ID1 levels by SJB2-043 exposure resulted from proteasomal degradation, since the proteasome inhibitor, MG-132, restored the levels of both proteins (Figure 2C, supplementary figure 1B).

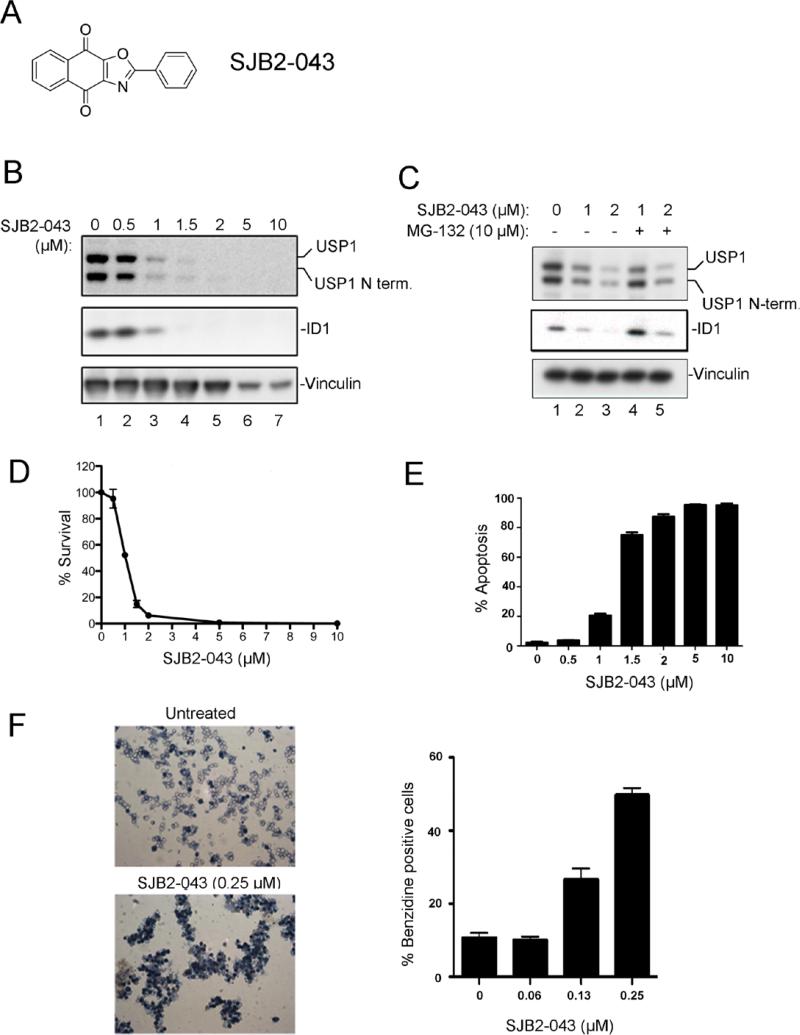

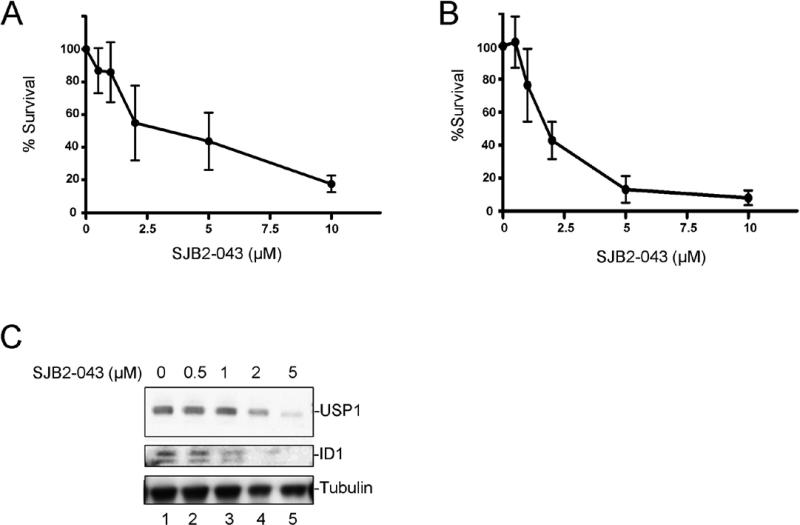

Figure 2. USP1 inhibitor promotes ID1 degradation and inhibits growth of the leukemic cell line K562.

(A) Chemical structure of USP1 inhibitor SJB2-043 (B) Western blots of lysates from K562 cells treated with DMSO or USP1 inhibitor SJB2-043 for 24 hrs. (C) Degradation of USP1 and ID1 in leukemic cells by USP1 inhibitor is proteasome mediated. Western blots of the lysates from K562 cells treated with SJB2-043 for 24 hrs followed by the treatment with MG-132 are shown. (D) Dose-dependent growth inhibition of K562 cells by USP1 inhibitor SJB2-043. Cells were grown in triplicate with DMSO or SJB2-043 for 24 hrs, and cytotoxicity was determined. (E) Induction of apoptosis in K562 cells treated with USP1 inhibitor. Cells were grown in triplicate with DMSO or SJB2-043 for 24 hrs, and apoptosis was determined. (F) Differentiation of K562 cells after treatments with low doses of USP1 inhibitor. Benzidine staining of the cells treated with SJB2-043 for 5 days is shown.

SJB2-043 also caused a decrease in the levels of other ID proteins, namely ID2 and ID3 in K562 cells (supplementary figure 1C). To determine whether the decrease in ID1 levels was secondary to a decrease in USP1 levels, we next generated a K562 stably transfected with a cDNA encoding doxycycline-induced shRNA to USP1. As expected, doxycycline exposure of these cells resulted in a dose-dependent decrease in USP1 expression (supplementary figure 2A). Moreover, depletion of USP1 by siRNA promoted ID1 degradation in K562 cells (supplementary figure 2B). Importantly, siRNA-mediated knockdown of USP1 in leukemic K562 cells resulted in growth inhibition, increased apoptosis and cell cycle arrest (Supplementary figures 2C, 2D, 2E, 2F). Collectively, these results indicated that while SJB2-043 may have off target effects, it exhibits its activity in K562 cells at least in part by promoting degradation of USP1 which results in ID1-ID3 degradation.

USP1 inhibitors are cytotoxic to leukemic cells

We next determined whether the USP1 inhibitors are cytotoxic to leukemic cells and whether the cytotoxicity results from ID1 degradation. K562 leukemic cells were treated with SJB2-043, and survival and differentiation were assessed. SJB2-043 caused a dose-dependent decrease in the number of viable K562 cells, with an EC50 of approximately 1.07 μΜ ± 0.08 (95% Confidence Limits) (Figure 2 D). Moreover, SJB2-043 induced apoptosis of K562 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2E). Cytotoxic drug concentrations correlated with the concentrations required for ID1 degradation. In addition, low dose treatments with SJB2-043 activated differentiation of K562 cells into hemoglobin-expressing erythroid cells, as detected by benzidine staining (Figure 2F).

In addition to the CML cells (K562 cells), we also evaluated the cytotoxicity of SJB2-043 in multiple acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cell lines. We chose AML cell lines which were engineered to express the Luciferase enzyme so that these cell lines can be used in future for in vivo optical imaging experiments. The AML cell lines, namely, MOLM14, OCI-AML3, U937 and SK-NO1 (Figure 3) expressed ID1 proteins. Upon treatment with SJB2-043, a dose-dependent cytotoxicity and concomitant ID1 degradation was observed in all of the AML cell lines (Figure 3) further suggesting the role of ID1 in leukemic cell survival.

Figure 3. USP1 inhibitor promotes ID1 degradation and causes cytotoxicity in multiple AML cell lines.

(A) Dose-dependent growth inhibition of MOLM14 cells by SJB2-043. Cells were grown in triplicate in presence of DMSO or SJB2-043 for 24 hrs, and cytotoxicity was determined. (B) Western blots of the lysates from MOLM14 cells treated with DMSO or SJB2-043 for 24 hrs. (C) Dose-dependent growth inhibition of Luciferase expressing AML cell lines by SJB2-043. Cells were grown in triplicate in the presence of DMSO or SJB2-043 for 24 hrs, and cytotoxicity was determined. (D) Western blots of the lysates from Luciferase expressing AML cells treated with DMSO or SJB2-043 for 24 hrs.

In order to determine if the cytotoxicity of the USP1 inhibitor was due to USP1/ID1 degradation, we next evaluated analogs of SJB2-043 in leukemic cells (Supplementary Figure 3). The USP1 inhibitor analogs (e.g. SJB2-127) with no significant activity on USP1 (IC50 >10 μM ) or ID1 degradation at concentrations upto 10 μΜ, did not exhibit cytotoxic effects on leukemic cells (supplementary figure 3A). The analog SJB2-109 had comparable biochemical inhibitory activity (IC50 =0.416 μM ) to our lead inhibitor SJB2-043 and exhibits comparable effects on ID1 degradation and leukemic cell survival. Importantly, a more potent analog SJB3-019A (IC50 = 0.0781 μM) was 5 times more potent than SJB2-043 in promoting ID1 degradation and cytoxicity in K562 cells.

To determine whether ID1 degradation resulted from USP1 inhibition and was not secondary to apoptosis, we next analyzed USP1/ID1 levels and apoptosis after treating K562 cells with SJB2-043 along with a caspase inhibitor in a time-course manner. USP1/ID1 degradation was observed as early as 7 hrs after the 2 μM of SJB2-043 exposure when apoptosis was not significant (supplementary figure 4A). At 18 hrs or 26 hrs (supplementary figures 4B, 4C) after the SJB2-043 exposure (2 μM), complete degradation of USP1/ID1 was observed with concurrent robust increase in apoptosis. As expected, caspase inhibitor treatment resulted in decreased apoptosis and inhibition of caspase activity (supplementary figures 4). However, ID1 degradation was not affected by caspase inhibition (supplementary figures 4, left panels). Even when the caspase activity was significantly abrogated with caspase inhibitor, the apoptosis was not completely blocked. These results suggest that ID1 degradation by SJB2-043 may not be occurring as a result of induction of apoptosis, although apoptosis may play a role in destabilizing ID1 independent of USP1 inhibition.

Collectively, these results indicated that novel USP1 inhibitors promote ID1 degradation by specifically targeting native USP1 and cause cytotoxicity in multiple leukemic cell lines.

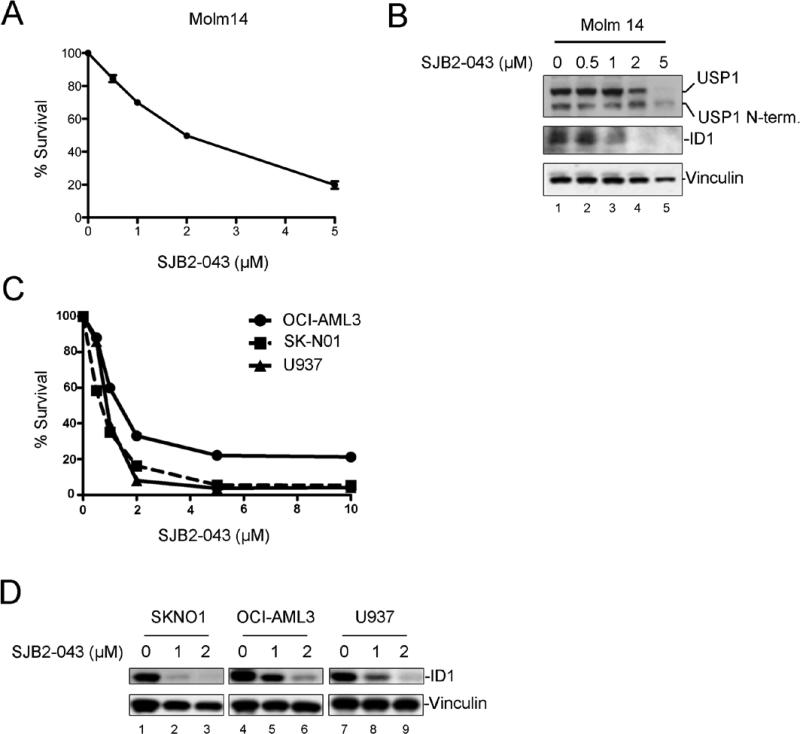

Pimozide, a known USP1 inhibitor, promotes ID1 degradation and inhibits leukemic cell growth

A known drug, Pimozide, is a weak USP1 non-competitive inhibitor (34). Pimozide may also inhibit STAT5 activation, thereby reducing the survival of BCR/ABL driven CML cells (35). We examined Pimozide for its possible cytotoxic effects on K562 cells (Figure 4) via destabilization of ID1. Interestingly, Pimozide promoted ID1 degradation, decreased USP1 levels, and caused a dose-dependent inhibition of K562 cell growth in vitro with induction of apoptosis (Figure 4B-D), though at a higher drug concentrations as compared to SJB2-043. The inhibitory drug concentrations correlated with the concentrations required for ID1 degradation. We next examined the effect of Pimozide in a mouse xenograft model of leukemia. K562 cells were injected into nude mice and xenografts were established followed by the treatment with Pimozide or Vehicle. As shown in Figure 4E, Pimozide treatment caused a modest inhibition of tumor growth. Taken together, Pimozide, a commercially available weak USP1 inhibitor, promotes ID1 degradation and inhibits leukemic cell growth in vitro and in vivo, suggesting that our more potent USP1 inhibitors may have a stronger anti-leukemic effect.

Figure 4. Treatment of K562 cells with a known USP1 inhibitor, Pimozide, leads to ID1 degradation and growth inhibition.

(A) Chemical structure of a known USP1 inhibitor Pimozide (B) Dose-dependent growth inhibition of K562 cells by Pimozide. Cells were grown in triplicate with DMSO or Pimozide for 48 hrs and cytotoxicity was determined. (C) Induction of apoptosis in K562 cells treated with Pimozide. Cells were grown in triplicate cultures, as described in “B”, and apoptosis was determined. (D) Western blots of the lysates from cells treated with DMSO or Pimozide for 48 hrs. (E) In vivo efficacy of Pimozide in K562 xenograft. Nude mice (n=10 per group) bearing xenografts of K562 cells were injected ip with Pimozide or Vehicle daily and tumor volumes (Tumor Volume = (width)2 × length/2)) were measured. P value = 0.0042 for Pimozide vs Vehicle groups, using paired t-test.

USP1 inhibitor promotes ID1 degradation and inhibits growth of primary AML cells from patients

Human AML precursor cells arise from leukemic stem cells (LSCs) and LSC differentiation is controlled through coordinate transcriptional regulation including the bHLH proteins. We therefore, tested whether the USP1 inhibitor also promotes ID1 degradation and cytoxicity in primary human leukemic cells. Primary fresh bone marrow and peripheral blood samples were acquired from AML patients and mononuclear cells were harvested. The cells were then exposed to USP1 inhibitor for 48-72 hrs in culture and ID1 levels as well as cell viability was determined. USP1 inhibitor SJB2-043 exhibited dose-dependent cytotoxicity on the primary bone marrow as well as peripheral blood from AML patients (Figure 5 A, B). Moreover, SJB2-043 treatment caused inactivation of USP1 and promoted ID 1 degradation in primary AML cells (Figure 5C). ID1 protein was detected as a doublet, which is likely due to the post-translational modification of the protein. These results demonstrate that USP1 inhibitor SJB2-043 inactivates native USP1 in primary AML cells and exhibits cytotoxicity. The selectivity of SJB2-043 against normal human hematopoietic cells was then examined in comparison to Pimozide using cord blood CD34+ cells. Whereas Pimozide was tolerated at high micromolar doses, low micromolar levels of SJB2-043 did result in growth inhibition of primary human cord blood CD34+ cells (Supplementary figure 5).

Figure 5. USP1 inhibitors promote ID1 degradation and growth inhibition of primary AML cells from patients.

Primary bone marrow cells or peripheral blood mononuclear cells from AML patients were cultured in triplicate cultures in the presence of DMSO or USP1 inhibitor, and cytotoxicity was determined. Survival plots of primary AML bone marrow cells (A) or peripheral blood cells (B) treated with DMSO or SJB2-043 for 48-72 hrs are shown. The data are from 3 different patient samples (N=3 ± SEM). (C) Western blots of the lysates from AML peripheral blood cells treated with SJB2-043 for 48 hrs.

USP1 inhibitor increases the levels of Ub-FANCD2 and disrupts the homologous recombination

Previous studies indicate that USP1 has other substrates besides ID1 (36). For instance, the USP1/UAF1 complex deubiquitinates the cellular monoubiquitinated substrates Ub-FANCD2 and Ub-PCNA (31, 37). Deubiquitination of FANCD2 is a critical step in the Fanconi anemia (FA)/BRCA DNA repair pathway (38, 39). Knockout or knockdown of USP1/UAF1 results in cellular hypersensitivity to DNA cross-linking chemotherapy agents such as Mitomycin C (40, 41). Murine knockout of USP1 results in cellular increase in Ub-FANCD2 and a mouse phenotype resembling FA (41). Knockout of USP1 also results in elevated levels of Ub-PCNA, leading to an increase in DNA translesion synthesis (TLS) (31).

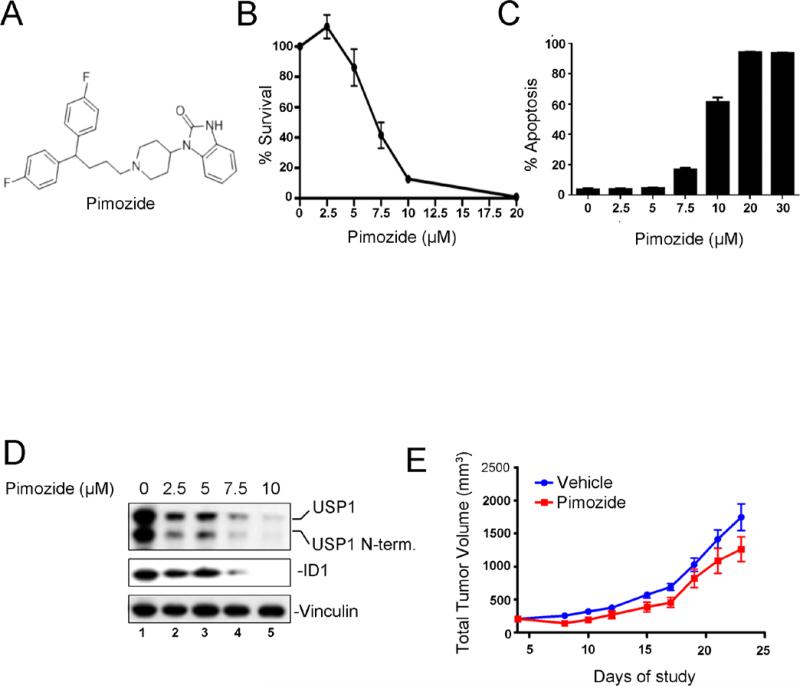

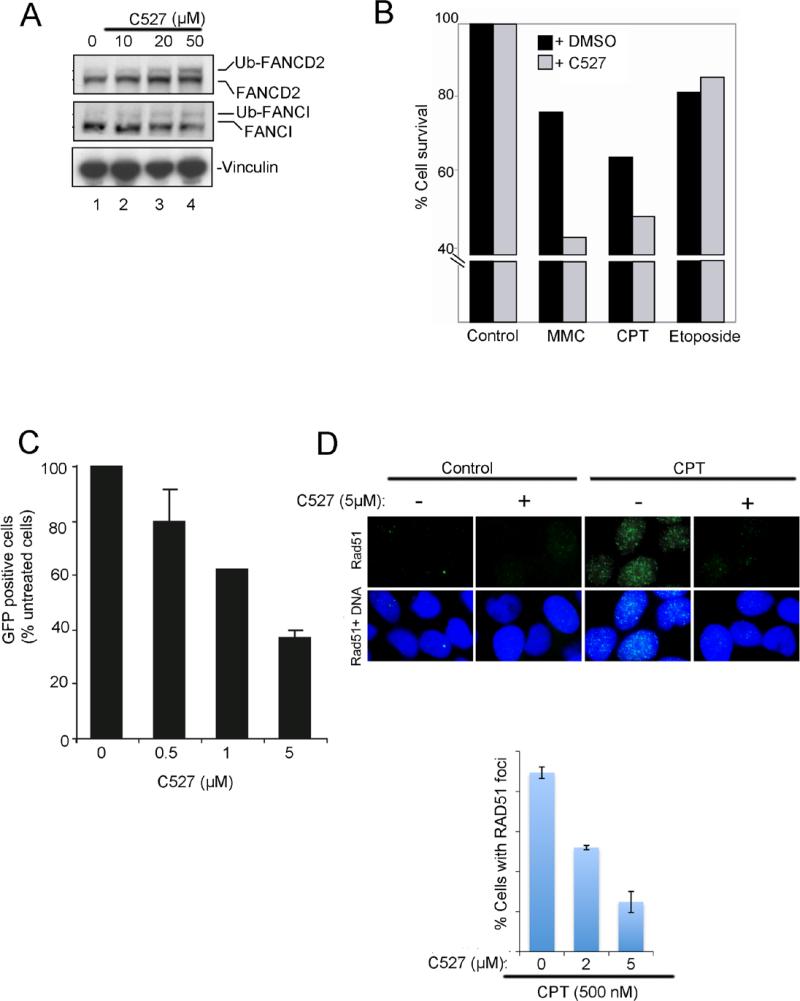

We next determined whether the USP1 inhibitors can alter cellular levels of Ub-FANCD2 and Ub-FANCI, a binding partner of FANCD2 (Figure 6). Hela cells were treated with USP1 inhibitor C527 and levels of FANCD2 and FANCI were determined by western blotting of the cell lysates. C527 treatments caused an increase in the levels of Ub-FANCD2 and Ub-FANCI (Figure 6A). SJB2-043 (another USP1 inhibitor) also increased the level of Ub-FANCD2 (supplementary figures 6A and 6B). An increase in Ub-PCNA was also observed in cells exposed to SJB2-043 (supplementary figure 6C) suggesting that besides FANCD2, PCNA is also affected by USP1 inhibition. Hela cells were next pre-treated with C527 followed by the treatment with DNA damaging agents including Mitomyin C, a DNA cross-linking agent. Pre-treatment of cells with USP1 inhibitor caused an enhancement in the cytoxicity of Mitomycin C and Camptothecin (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. USP1 inhibitor increases the levels of Ub-FANCD2, decreases the HR activity, and sensitizes the cells to chemotherapy agents.

(A) Western blots of the lysates from Hela cells treated with DMSO or USP1 inhibitor C527 for 8 hrs. (B) Increased cytotoxicity of C527 on Hela cells in presence of chemotherapy agents. Cells were treated with C527 (1 μM) for 24 hrs, followed by the treatment with Mitomycin C (MMC) (0.25 μM), Camptothecin (CPT) (0.1 μM) or Etoposide (0.5 μM) for 4 days, and cell survival was determined. (C) C527 inhibits DRGFP reporter for homologous recombination repair activity. U2OS-DRGFP cells were transfected with I-SCE-I reporter plasmid and then exposed to C527 at the indicated concentration for 24 h. Cells were then subjected to flow cytometry analysis. The percentage of GFP positive cells was normalized by solvent vehicle treated group are shown. (D) C527 inhibits camptothecin-induced RAD51 foci formation. HeLa cells were pre-treated with DMSO or C527 at the indicated concentration and then exposed to camptothecin (CPT) for 1 hr. RAD51 foci were detected using immunofluorescence. Data are represented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments.

Since disruption of USP1 activity results in decreased homologous recombination (HR) (41), we next used a gene conversion assay to examine the effect of USP1 inhibitor on cellular HR activity. Interestingly, C527 treatments caused a dose-dependent decrease in gene conversion (Figure 6C), based on the measurement of cellular GFP in this assay. We also confirmed HR defect by evaluating Rad51 foci formation, another surrogate marker of cellular HR activity (Figure 6D). C527 inhibited Camptothecin induced the Rad51 foci in Hela cells. The more active USP1 inhibitor SJB3-019A also increased the levels of Ub-FANCD2 and Ub-PCNA, and decreased the HR activity (supplementary figures 6D-F). Taken together, these results suggest that USP1 inhibitor treatments lead to an increase in ubiquitinated forms of FANCD2 and FANCI, causes a decrease in HR activity, and sensitizes cells to DNA damaging agents.

DISCUSSION

ID1 is essential for proliferation and maintenance of many cancer types (14, 42). However, it has not yet been therapeutically targeted with a small molecule in leukemia. Here, we demonstrate that targeting USP1 with a small molecule, can promote ID1 degradation and cell death in multiple leukemic cell lines. Our data demonstrate that ID1 can be targeted even in primary human leukemic cells using novel inhibitors of USP1.

The drug of choice for chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) is Imitanib, although drug resistance remains a problem. Novel therapies are also needed for the cure of acute myelogenous leukemia (AML), the most common acute leukemias of adults. USP1 inhibitors represent a novel class of drugs for these cancers. USP1 inhibitors can degrade ID1, promote differentiation, and induce apoptosis in these types of leukemic cells and can be potential therapeutic agents. ID1 blocks cellular differentiation at least in part, through its repressive effect on the expression of cell cycle inhibitor p21 (20). Consistent with this previous report (20), our USP1 inhibitor C527 promotes the degradation of ID1 and the concurrent upregulation of p21 in mouse osteosarcoma cells (supplementary figure 6B). Cell cycle arrest through p21 upregulation provides a mechanistic explanation for the increase in erythroid differentiation of leukemic cells. ID proteins have central role in keeping cells in an immature state. Various reports suggest that ID proteins including ID1 play an important role in maintaining cancer-initiating cells in a variety of solid tumors (10, 19, 43, 44). Therefore, therapeutically targeting ID1 may also eradicate leukemic cancer stem cells.

An inhibitor of USP1, Pimozide, was recently identified (34). Pimozide, an antipsychotic drug, is currently FDA approved for treatment of Tourrete's syndrome. However, its efficacy in promoting ID1 degradation has not been previously reported. In our studies, Pimozide promotes ID1 degradation and causes cytoxicity in leukemic cells. Our in vivo studies using Pimozide showed a modest decrease in tumor volume in xenograft models of K562 leukemic cells. This is consistent with the recent report by Nelson et al (45) who observed a modest effect of Pimozide in FLT3-AML-driven tumor models. Of note, the EC50 of Pimozide on leukemic cells is significantly higher than our novel USP1 inhibitors. Even though Pimozide is currently used in humans for the treatment of Tourrete's syndrome, its efficacy in mouse tumor models is limited due to its toxicity. Accordingly, at the maximum tolerated doses, Pimozide may not be an effective anti-cancer agent, at least in leukemic mouse models. Moreover, in addition to exhibiting an inhibitory activity to USP1, it also abrogates STAT5 activity in leukemic cells (35, 45).

ID1 plays an important role in invasiveness of many cancer types including breast and brain tumors (11, 46, 47). Specifically, ID1 depletion by antisense oligos to ID1 in BCR-ABL bearing 32D3 cells significantly reduces its invasiveness in vitro and in vivo SCID mouse models via MMP9 axis (48). It remains to be investigated if our small molecule inhibitors of USP1 can reduce the invasiveness of leukemic cells. Although ID1 has been previously targeted using peptide-conjugated anti-sense oligomers (49), peptide aptamers (50), or cannabidiol (11) as potential ways to inhibit ID1 function in solid tumors, none of these applications have been explored for leukemia.

The USP1 inhibitors reported in this study may have other advantages, since USP1 has other known substrates (31, 37). We have previously shown that USP1, in complex with its stimulatory binding partner, UAF1, deubiquitinates the Fanconi Anemia (FA) proteins, FANCD2 and FANCI (24). Knockdown of USP1 activity results in elevated cellular levels of Ub-FANCD2, resulting in disruption of the FA pathway (40, 41). Functional Fanconi anemia DNA repair pathway is required for cellular resistance to DNA cross-linking agents and FA pathway deficient cells including USP1−/− cells are hypersensitive to DNA cross-linking agents (39-41). USP1 inhibitors may therefore block the FA pathway, thereby promoting cellular hypersensitivity to DNA crosslinking agents and chromosome instability. In the short run, USP1 inhibitors may therefore have an additional useful function as anti-cancer agents, by sensitizing tumors to conventional chemotherapeutic agents, e.g. Cisplatin (34). In our study, USP1 inhibitors increased the levels of Ub-FANCD2, decreased the HR activity, and sensitized cells to chemotherapy agents Mitomycin C and Camptothecin. The increase in Ub-FANCD2 may result directly from USP1 inhibition or indirectly from the DNA damage incurred by USP1 inhibitor exposure. In either case, USP1 inhibition may have additional anti-cancer functions which extend beyond the promotion of cellular differentiation. Accordingly, the inhibitors may be useful as radiation or cisplatin sensitizers, based on their ability to disrupt the FA/BRCA or TLS pathways.

In summary, we have identified novel small molecule inhibitors of USP1 which exhibit nanomolar IC50 for USP1 activity. These inhibitors also promote ID1 degradation and cause cytotoxicity in a variety of leukemic cell lines and primary leukemic cells. Further preclinical assessment of these small molecules in mouse models will determine their efficacy as novel anti-cancer agents. If successful, these newly identified USP1 inhibitors can have broader implications and can be valuable therapeutic agents for not only leukemia but also for other cancer types (e.g. breast cancer and glioblastoma) in which ID1 may be a prime therapeutic target.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Anna Blachman, Kevin O'Connor, and Benjamin Primack for their technical assistance. The authors also thank Jung Min Kim for her help in generating the data on p21 expression.

Grant support: This research was supported by a Translational Research Grant from the Leukemia Lymphoma Society (6237-13) and the National Institutes of Health grants (1RC4 DK090913-01, 2P01HL048546, 2RO1 DK43889 and 5R37HL52725-18) to A. D. D'Andrea.

Footnotes

The authors disclose no potential conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lasorella A, Uo T, Iavarone A. Id proteins at the cross-road of development and cancer. Oncogene. 2001;20:8326–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benezra R, Davis RL, Lockshon D, Turner DL, Weintraub H. The protein Id: a negative regulator of helix-loop-helix DNA binding proteins. Cell. 1990;61:49–59. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90214-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langlands K, Yin X, Anand G, Prochownik EV. Differential interactions of Id proteins with basic-helix-loop-helix transcription factors. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:19785–93. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.32.19785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Norton JD. ID helix-loop-helix proteins in cell growth, differentiation and tumorigenesis. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:3897–905. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.22.3897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maruyama H, Kleeff J, Wildi S, Friess H, Buchler MW, Israel MA, et al. Id-1 and Id-2 are overexpressed in pancreatic cancer and in dysplastic lesions in chronic pancreatitis. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:815–22. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65180-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schindl M, Oberhuber G, Obermair A, Schoppmann SF, Karner B, Birner P. Overexpression of Id-1 protein is a marker for unfavorable prognosis in early-stage cervical cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5703–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schindl M, Schoppmann SF, Strobel T, Heinzl H, Leisser C, Horvat R, et al. Level of Id-1 protein expression correlates with poor differentiation, enhanced malignant potential, and more aggressive clinical behavior of epithelial ovarian tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:779–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ouyang XS, Wang X, Lee DT, Tsao SW, Wong YC. Over expression of ID-1 in prostate cancer. J Urol. 2002;167:2598–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin CQ, Singh J, Murata K, Itahana Y, Parrinello S, Liang SH, et al. A role for Id-1 in the aggressive phenotype and steroid hormone response of human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1332–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Brien CA, Kreso A, Ryan P, Hermans KG, Gibson L, Wang Y, et al. ID1 and ID3 regulate the self-renewal capacity of human colon cancer-initiating cells through p21. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:777–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soroceanu L, Murase R, Limbad C, Singer EL, Allison J, Adrados I, et al. Id-1 is a key transcriptional regulator of glioblastoma aggressiveness and a novel therapeutic target. Cancer Res. 2013;73:1559–69. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheung HW, Ling MT, Tsao SW, Wong YC, Wang X. Id-1-induced Raf/MEK pathway activation is essential for its protective role against taxol-induced apoptosis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:881–7. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu H, Han HY, Wang YL, Zhang XP, Chua CW, Wong YC, et al. The role of Id-1 in chemosensitivity and epirubicin-induced apoptosis in bladder cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2009;21:1053–9. doi: 10.3892/or_00000323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fong S, Debs RJ, Desprez PY. Id genes and proteins as promising targets in cancer therapy. Trends Mol Med. 2004;10:387–92. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yokota Y, Mori S. Role of Id family proteins in growth control. J Cell Physiol. 2002;190:21–8. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang R, Hirsch P, Fava F, Lapusan S, Marzac C, Teyssandier I, et al. High Id1 expression is associated with poor prognosis in 237 patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2009;114:2993–3000. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-223115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tam WF, Gu TL, Chen J, Lee BH, Bullinger L, Frohling S, et al. Id1 is a common downstream target of oncogenic tyrosine kinases in leukemic cells. Blood. 2008;112:1981–92. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-103010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suh HC, Leeanansaksiri W, Ji M, Klarmann KD, Renn K, Gooya J, et al. Id1 immortalizes hematopoietic progenitors in vitro and promotes a myeloproliferative disease in vivo. Oncogene. 2008;27:5612–23. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perk J, Iavarone A, Benezra R. Id family of helix-loop-helix proteins in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:603–614. doi: 10.1038/nrc1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams SA, Maecker HL, French DM, Liu J, Gregg A, Silverstein LB, et al. USP1 deubiquitinates ID proteins to preserve a mesenchymal stem cell program in osteosarcoma. Cell. 2011;146:918–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lasorella A, Stegmuller J, Guardavaccaro D, Liu G, Carro MS, Rothschild G, et al. Degradation of Id2 by the anaphase-promoting complex couples cell cycle exit and axonal growth. Nature. 2006;442:471–4. doi: 10.1038/nature04895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bounpheng MA, Dimas JJ, Dodds SG, Christy BA. Degradation of Id proteins by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Faseb J. 1999;13:2257–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kong Y, Cui H, Zhang H. Smurf2-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of Id1 regulates p16 expression during senescence. Aging Cell. 2011;10:1038–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00746.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohn MA, Kowal P, Yang K, Haas W, Huang TT, Gygi SP, et al. A UAF1-containing multisubunit protein complex regulates the Fanconi anemia pathway. Mol Cell. 2007;28:786–97. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mermerian AH, Case A, Stein RL, Cuny GD. Structure-activity relationship, kinetic mechanism, and selectivity for a new class of ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase-L1 (UCH-L1) inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:3729–32. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohn MA, Kee Y, Haas W, Gygi SP, D'Andrea AD. UAF1 is a subunit of multiple deubiquitinating enzyme complexes. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:5343–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808430200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kee Y, Yang K, Cohn MA, Haas W, Gygi SP, D'Andrea AD. WDR20 regulates activity of the USP12 x UAF1 deubiquitinating enzyme complex. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:11252–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.095141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vinciguerra P, Godinho SA, Parmar K, Pellman D, D'Andrea AD. Cytokinesis failure occurs in Fanconi anemia pathway-deficient murine and human bone marrow hematopoietic cells. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:3834–42. doi: 10.1172/JCI43391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pierce AJ, Johnson RD, Thompson LH, Jasin M. XRCC3 promotes homology-directed repair of DNA damage in mammalian cells. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2633–8. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.20.2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang M, Kim JM, Shiotani B, Yang K, Zou L, D'Andrea AD. The FANCM/FAAP24 complex is required for the DNA interstrand crosslink-induced checkpoint response. Mol Cell. 2010;39:259–68. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang TT, Nijman SM, Mirchandani KD, Galardy PJ, Cohn MA, Haas W, et al. Regulation of monoubiquitinated PCNA by DUB autocleavage. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:339–47. doi: 10.1038/ncb1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borodovsky A, Ovaa H, Kolli N, Gan-Erdene T, Wilkinson KD, Ploegh HL, et al. Chemistry-based functional proteomics reveals novel members of the deubiquitinating enzyme family. Chem Biol. 2002;9:1149–59. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00248-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Piatkov KI, Colnaghi L, Bekes M, Varshavsky A, Huang TT. The auto-generated fragment of the usp1 deubiquitylase is a physiological substrate of the N-end rule pathway. Mol Cell. 2012;48:926–33. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen J, Dexheimer TS, Ai Y, Liang Q, Villamil MA, Inglese J, et al. Selective and cell-active inhibitors of the USP1/ UAF1 deubiquitinase complex reverse cisplatin resistance in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Chem Biol. 2011;18:1390–1400. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelson EA, Walker SR, Weisberg E, Bar-Natan M, Barrett R, Gashin LB, et al. The STAT5 inhibitor pimozide decreases survival of chronic myelogenous leukemia cells resistant to kinase inhibitors. Blood. 2011;117:3421–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-255232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang TT, D'Andrea AD. Regulation of DNA repair by ubiquitylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:323–34. doi: 10.1038/nrm1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nijman SM, Huang TT, Dirac AM, Brummelkamp TR, Kerkhoven RM, D'Andrea AD, et al. The deubiquitinating enzyme USP1 regulates the Fanconi anemia pathway. Mol Cell. 2005;17:331–9. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garcia-Higuera I, Taniguchi T, Ganesan S, Meyn MS, Timmers C, Hejna J, et al. Interaction of the Fanconi anemia proteins and BRCA1 in a common pathway. Mol Cell. 2001;7:249–62. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00173-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim H, D'Andrea AD. Regulation of DNA cross-link repair by the Fanconi anemia/BRCA pathway. Genes Dev. 2012;26:1393–408. doi: 10.1101/gad.195248.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oestergaard VH, Langevin F, Kuiken HJ, Pace P, Niedzwiedz W, Simpson LJ, et al. Deubiquitination of FANCD2 is required for DNA crosslink repair. Mol Cell. 2007;28:798–809. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim JM, Parmar K, Huang M, Weinstock DM, Ruit CA, Kutok JL, et al. Inactivation of murine Usp1 results in genomic instability and a Fanconi anemia phenotype. Dev Cell. 2009;16:314–20. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ruzinova MB, Benezra R. Id proteins in development, cell cycle and cancer. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:410–18. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(03)00147-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nam HS, Benezra R. High levels of Id1 expression define B1 type adult neural stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:515–26. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anido J, Saez-Borderias A, Gonzalez-Junca A, Rodon L, Folch G, Carmona MA, et al. TGF-beta receptor inhibitors target the CD44(high)/Id1(high) glioma-initiating cell population in human glioblastoma. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:655–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nelson EA, Walker SR, Xiang M, Weisberg E, Bar-Natan M, Barrett R, et al. The STAT5 inhibitor Pimozide displays efficacy in models of acute myelogenous leukemia driven by FLT3 mutations. Genes Cancer. 2012;3:503–11. doi: 10.1177/1947601912466555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lyden D, Young AZ, Zagzag D, Yan W, Gerald W, O'Reilly R, et al. Id1 and Id3 are required for neurogenesis, angiogenesis and vascularization of tumour xenografts. Nature. 1999;401:670–77. doi: 10.1038/44334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fong S, Itahana Y, Sumida T, Singh J, Coppe JP, Liu Y, et al. Id-1 as a molecular target in therapy for breast cancer cell invasion and metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13543–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2230238100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nieborowska-Skorska M, Hoser G, Rink L, Malecki M, Kossev P, Wasik MA, et al. Id1 transcription inhibitor-matrix metalloproteinase 9 axis enhances invasiveness of the breakpoint cluster region/abelson tyrosine kinase-transformed leukemia cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4108–116. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Henke E, Perk J, Vider J, de Candia P, Chin Y, Solit DB, et al. Peptide-conjugated antisense oligonucleotides for targeted inhibition of a transcriptional regulator in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:91–100. doi: 10.1038/nbt1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mern DS, Hasskarl J, Burwinkel B. Inhibition of Id proteins by a peptide aptamer induces cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:1237–44. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.