Abstract

Chemoresistance is a major impediment to the successful treatment of cancer. It involves various mechanisms, including defects in the apoptosis program that is induced by anticancer drugs. To further explore the mechanisms underlying the development of chemoresistance in ovarian carcinoma after cisplatin (CDDP) treatment, we compared the effect of CDDP on expression of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP), a direct inhibitor of caspase-3, -7, and -9, Fas, Fas-ligand (Fas-L), and pro- and antiapoptotic proteins in a CDDP-sensitive human ovarian carcinoma cell line (2008) and its CDDP-resistant subclone (2008C13). In this article, we show that cisplatin treatment led to a differential expression of distinct apoptotic targets in the CDDP-sensitive cell line (2008) and its CDDP-resistant subclone (2008C13). The acquisition of cisplatin resistance was associated with the ability of the treated cells to enhanced expression of XIAP, whereas the death inducer Fas-L was abrogated in 2008C13 following treatment with CDDP. However, the CDDP-sensitive cells failed to activate XIAP but increased Fas-L expression, indicating that distinct regulatory mechanisms are operative. These findings suggest that the expression of XIAP and downregulation of Fas-L are linked to chemoresistance in ovarian carcinoma cells and may represent one of the potential antiapoptotic mechanisms involved during this process.

Keywords: Cisplatin, Apoptosis, Chemoresistance, XIAP, Fas-L, Ovarian carcinoma

Cisplatin [cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II)] (CDDP2) is one of the most widely used chemotherapeutic agents for the treatment of human ovarian cancer and other tumors (1,2). Despite its usefulness in these diseases, the appearance of drug resistance or the development of a defective apoptotic program are frequent occurrences in these tumors and remain major obstacles to treatment success (3–6). Numerous mechanisms have been found to contribute to the resistance to CDDP; these include impaired cellular drug uptake, increased drug efflux, enhanced intracellular detoxification, increased in DNA repair activity, and tolerance in platinum adducts. However, the precise molecular steps implicated in the induction of this resistance remain unknown. Difference in signal transduction activity in response to chemotherapy could provide insight regarding the ultimate outcome of the treatment.

In this study, we investigated molecules in the apoptosis pathway that might be regulated differentially by CDDP treatment in CDDP-sensitive and CDDP-resistant ovarian cancer cells. The expression of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) or proapoptotic proteins such as Bax, Bcl-xs, and Fas-L was assessed. Our data indicate that CDDP treatment results in inhibition of XIAP and activation of proapoptotic proteins like Bax, Bcl-xs, and Fas-L in the CDDP-sensitive 2008 cells. On the other hand, an increase in the level of XIAP and inhibition of apoptosis inducers such as Bax, Bcl-xs, and Fas-L appeared following drug treatment in the CDDP-resistant 2008C13 cells. Our findings suggest that acquired chemoresistance could have resulted from the induction of XIAP and should involve an impairment of the apoptotic pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

CDDP-sensitive (2008) and CDDP-resistant (2008CI3) ovarian cancer cells were kindly provided by Drs. S. B. Howell (University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA), S. G. Chaney (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC), and Z. H. Siddik (M.D. Anderson, Houston, TX) (7). CDDP (platinol-AQ cisplatin injection) was purchased from Bristol Laboratories (Princeton, NJ).

Cell Lines

Human ovarian cancer cells 2008 and their CDDP-resistant variant 2008C13 cells were cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere in RPMI-1640 medium (Life Technologies, Inc., Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 1% nonessential amino acids, 10% fetal calf serum (Life Technologies, Inc.), and 1% streptomycin-penicillin.

Immunoblot Analysis

Cells growing exponentially were treated or not with 20 μM CDDP for 1 h, after which they were washed and fresh drug-free medium was added. At different times after drug exposure, the cells were collected and lysed as previously described (8). Proteins (70 μg) were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE transferred onto PVDF membrane (Immobilon; Millipore, Bedford, MA). After blocking with 5% milk in phosphate-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween-20 for 1 h, the membranes were probed with anti-p53 (BD-Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), anti-p2l (BD-Pharmingen), anti-Bcl-xs, (Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA), and anti-Bax (Santa Cruz). The antibody–antigen complexes were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ).

Cell Growth Assay

The cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 2 × 103 cells per well. Twenty-four hours later, the cells were treated with CDDP for 1 h, washed, seeded, and left to proliferate for 4–5 days. The number of surviving cells was measured by nucleic acid staining with the CyQUANT Cell Proliferation Assay Kit (Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, OR) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The samples were analyzed on a Fluoroskan Ascent CF microplate fluorometer (ThermoLab-Systems; Helsinki, Finland). All experiments were done in quadruplicate, and the proliferation rate was expressed as the ratio of the number of proliferating cells treated with CDDP to that of cells not treated with CDDP.

DNA Fragmentation Analysis

The nucleosomal DNA degradation was analyzed as described previously (9). Briefly, 1 × 105 cultured cells were seeded in 6-cm culture dishes and allowed to adhere overnight. Cisplatin-treated and untreated cells were harvested and then lysed in a solution containing 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 25 mM EDTA, and 0.5% SDS. After centrifugation, the supernatants were incubated with 300 μg/ml proteinase K for 5 h at 65°C and extracted with phenol-chloroform. The aqueous layer was treated with 0.1 volume of 3 M sodium acetate, and the DNA was precipitated with 2.5 volumes of 95% ethanol. After treatment with 100 μg/ml RNase A for 1 h at 37°C, the sample (10 μg) was electrophoresed on a 2% agarose gel and transferred by Southern blot using the human Cot-1 DNA (Gibco-Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) as a probe.

Reverse Transcriptase-PCR and DNA Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from 2008 and 2008C13 cells by using the RNeasy mini Kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. First-strand cDNA was prepared by reverse transcription (RT) of 2 μg of RNA in a 20-μl reaction volume containing 10× PCR buffer, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, and 5 μM random primers (superscript reverse transcriptase; Life Technologies). PCR amplifications were performed in a 50-μl reaction volume containing 5 μl of cDNA, with a master mix composed of 10× PCR buffer, 1 mM MgCl2, 200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 2.5 U of AmpliTaq Gold (Perkin Elmer, Norwalk, CT), and 20 nM of each primer.

Primers used were as follows. Human Fas sense (5′-ATT TCT GCC ACT GCA GCC CTC AGG-3′) and anti-sense (5′-TCC AGT TCG CTG GGC AGA CTT CTC-3′); human Fas-L sense (5′-ATG TTT CAG CTC TTC CAC CTA CAG A-3′) and antisense (5′-CCA GAG AGA GCT CAG ATA CGT TGA C-3′); and human β-actin sense (5′-TGA CGG GGT CAC CCA CAC TGT GCC CAT CTA-3′) and antisense (5′-CTA GAA TTT GCG GTC GAC GAT GGA GGG-3′), covering the 76–706 region of Fas cDNA, the 365–856 region of Fas-L cDNA, and the 2199–3065 region of β-actin cDNA and giving PCR products of 630, 492, and 867 bp, respectively (10). XIAP sense (5′-AGC ATC AAC ACT GGC ACG AGC AGG-3′) and antisense (5′-TGT TCC CAA GGG TCT TCA CTG GGC-3′); the human GAPDH sense (5′-CCC ATG GCA AAT TCC ATG GCA CC-3′) and antisense (5′-TGT CAT GGA TGA CCT TGG CCA GG-3′) spanning the 162–989 nucleotide region of XIAP and the 188–532 region of GAPDH cDNAs and yielding 827-and 344-bp PCR products, respectively. Conditions for the PCR reaction consisted of an initial denaturation step at 94°C for 5 min followed by 35 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at either 57°C (for Fas) or 61°C (for Fas-L and β-actin) or 55°C for XIAP and GAPDH), and 30 s at 72°C. After a final extension at 72°C for 5 min, RT-PCR products were subjected to electrophoresis on 1.2% agarose gels and stained by ethidium bromide. The Fas, Fas-L, and XIAP products were subsequently confirmed by direct sequencing.

RESULTS

Cisplatin-Induced Apoptosis in Ovarian Carcinoma Cells

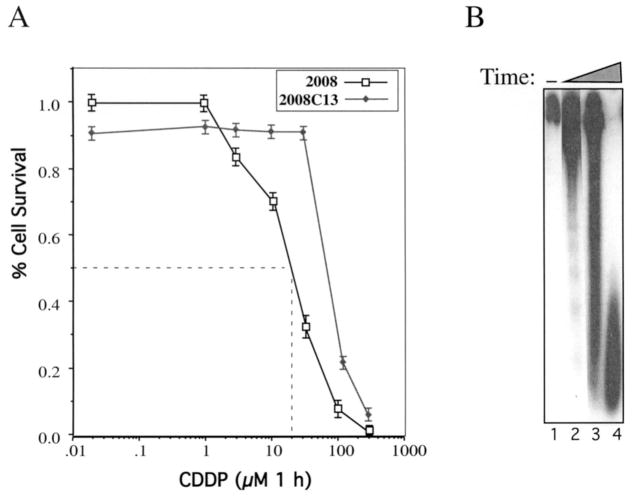

The CDDP-sensitive 2008 cells were derived from a patient with serous cystadenocarcinoma of the ovary, and its resistant subclone 2008CI3 was established from 2008 by in vitro exposure to platinum anticancer agents (7). To mimic in vivo chemotherapy, cells were incubated with CDDP for 1 h, after which the drug was washed out. The dose response and time course for the induction of apoptosis were determined by cell viability, DNA ladder (Fig. 1), and examination of DAPI-stained cells microscopically (data not shown). DNA fragmentation was observed from 3, 6, and 24 h after the treatment of 2008 cells with 20 μM of CDDP in 2008 cells (Fig. 1B). However, no DNA fragmentation was observed in CDDP-resistant cells (data not shown).

Figure 1.

CDDP-induced apoptosis in ovarian carcinoma cells. (a) Dose response of CDDP-induced apoptosis. The 2008 and 2008C13 cells were incubated for 1 h in 96-well plates (2 × 103 cells/well) with CDDP at the concentrations indicated, then cultured in a fresh CDDP-free medium for the remaining time. The percentage of live cells was measured 4 days later by using a fluorescence-based nucleic acid method for cell viability (CyQUANT cell proliferation assay kit). (b) Analysis of CDDP-induced DNA fragmentation pattern. The 2008 ovarian carcinoma cells were treated with 20 μM of CDDP for 1 h, and cells were collected at the indicated time for DNA fragmentation analysis.

Expression of the Members of Pro- and Antiapoptotic Proteins in Sensitive and Resistant Cells After CDDP Treatment

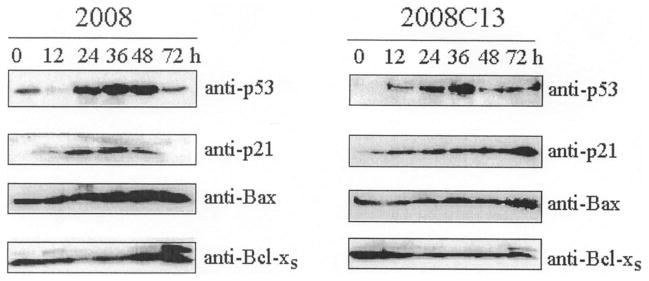

DNA-damaging drugs are known to activate the tumor suppressor gene p53, where function relates to cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and sensitivity to chemotherapy (11–13). Therefore, p53 expression was investigated after CDDP treatment, in parallel with induction of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p2lCIP/WAF1, a p53-dependent gene (14). As depicted by Western blot analysis (Fig. 2), p53 accumulated in ovarian carcinoma cells in response to CDDP at a level 10-fold higher than un- treated cells. Western blot of p2l show the induction of this protein in parallel with p53 accumulation in response to CDDP (Fig. 2). Next, we analyzed the expression of members of the Bcl-2 family such as the pro-apoptotic proteins Bax and Bcl-xs (15–17). Increases in antiapoptotic proteins have been suggested to be responsible for resistance to apoptosis under numerous physiopathologic situations (18). Western blot analysis of 2008 and 2008C13 cell extracts following CDDP treatment was performed using anti-p53, anti-p21, anti-Bax and Bcl-xs antibodies (Fig. 2). Strong upregulation of p53 protein level followed by its target gene product p2l was observed after 24 h of treatment of 2008 and 2008C13 cells. In addition, induction of proapoptotic proteins such as Bax and Bcl-xs was observed between 36 and 72 h after CDDP treatment of 2008 cells (Fig. 2). Interestingly, the CDDP-resistant clones did not express these proapoptotic molecules and remained at their basal level following drug treatment (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Expression of pro- and antiapoptotic proteins in CDDP-treated ovarian carcinoma 2008 and 2008Cl3 cells. CDDP-sensitive and CDDP-resistant cells were treated for 1 h with 20 μM CDDP. At the indicated time, whole cell lysates were prepared and proteins were separated (70 μg) and analyzed by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies.

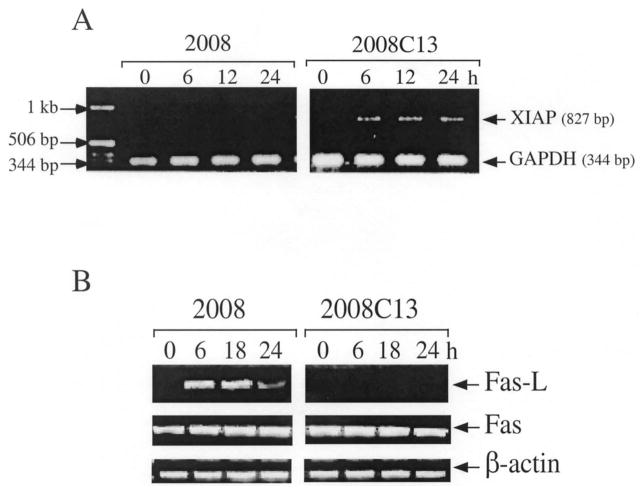

CDDP Enhances XIAP Upregulation and Fas-L Inhibition in CDDP-Resistant Cells

To investigate whether the antiapoptotic target XIAP and death-inducer Fas/Fas-L system were a target of CDDP-induced genotoxic stress, we examined whether the exposure of ovarian carcinoma cells to CDDP affected the expression of these genes. Following CDDP treatment, inhibition of XIAP mRNA expression was observed in CDDP-sensitive 2008 cells. However, XIAP induction was detected in the CDDP-resistant 2008C13 clones beginning 6 h after treatment and persisting through the next 24 h (Fig. 3a). In the case of Fas-L, mRNA was upregulated only in the CDDP-sensitive cells starting 6 h after drug treatment until 24 h, but was not detected in the resistant clones (Fig. 3b), even at higher concentration of CDDP (40 μM) (data not shown). In contrast, Fas receptor mRNA did not change following CDDP treatment and was comparable in both cell lines (Fig. 3b). Thus, CDDP led to the induction of Fas-L mRNA expression in chemosensitive 2008 cells and XIAP upregulation in chemoresistant 2008C13 cells. Therefore, genotoxic stress can signal to activate apoptosis induction in CDDP-sensitive cells and antiapoptotic mechanisms in the CDDP-resistant cells, indicating a defect in programmed cell death control leading to a survival mechanism in the chemoresistant cells.

Figure 3.

Expression of XIAP and Fas/Fas-L following CDDP treatment. (a) Fas-L mRNA was enhanced in 2008 cells and abrogated in 2008C13 cells after stimulation with CDDP. Cells were incubated with medium or with 20 μM CDDP for 1 h. At time points indicated, total RNA was purified, and the expression of Fas-L and β-actin mRNAs was examined by RT-PCR using specific primers. (b) Same experiment as in (a) with XIAP and GAPDH as the specific primer pairs.

DISCUSSION

Failure of cells to undergo apoptosis or programmed cell death may contribute to the development of chemotherapy resistance (19,20). Essentially all currently available cytotoxic drugs induce tumor cell death by triggering apoptosis, and most drugs target dividing cells. Resistance to chemotherapy is a major reason for treatment failure in ovarian cancer (3,4). Defects in the regulation of proteins controlling apoptosis may render these quiescent cells resistant to certain chemotherapeutic drugs.

Bcl-2 family proteins regulate apoptosis, some antagonizing cell death and others facilitating it. In particular, the Bcl-2 protein and its close homologue Bcl-xL confer resistance to cytotoxic drug-induced damage (21) in ovarian carcinoma (22). Unlike Bcl-2 family proteins, inhibitors of apoptosis proteins (IAPS) are a family of antiapoptotic proteins that are highly conserved across several species and they block apoptotic events by directly binding and inhibiting selected caspases (23). Thus far, at least five human IAP proteins have been described: NIAP, clAP-1, clAP-2, XIAP, and survivin (24). Although their role in human ovarian epithelial cancer and chemotherapy resistance are unknown, recent studies suggested that the expression of IAP genes might be regulated by nuclear transcription factors (25–27). It is therefore possible that differences in the signal transduction pathway activated in response to cisplatin in CDDP-sensitive and CDDP-resistance cells may be an important determinant to an apoptotic program and survival response.

In the present study, we examined the effect of CDDP on XIAP and Fas/Fas-L expression and activation of pro- and antiapoptotic targets in sensitive versus resistant cell lines. Our results showed that CDDP markedly inhibits XIAP mRNA expression and upregulates Fas-L in the drug-sensitive 2008 cells (Fig. 3). IAP family members inhibit caspase activation by inhibiting apoptosome formation, which is composed of cytochrome c/Apaf-1/caspase-9 (24,28). Thus, blocking of IAP protein expression results in caspase activation and apoptosis enhancement in CDDP-sensitive cells. Therefore, CDDP-induced XIAP upregulation is believed to enhance drug-induced apoptosis.

Taken together, our data provide a basis for understanding the molecular basis of chemosensitivity versus chemoresistance in ovarian cancer by demonstrating a central role for XIAP and Fas-L in drug-induced apoptosis. The cytotoxic action of drugs used in chemotherapy of ovarian carcinoma may involve several levels of interference with apoptosis pathways that include triggering of Fas/Fas-L interaction (autocrine suicide) (10, 29,30), activation of several signal transduction pathways (stress kinases) [(31,32), data not shown and A. Mansouri et al., manuscript submitted], and activation of effector molecules such as interleukin-1 beta-converting enzyme (ICE)-like proteases (33,34).

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to S. B. Howell, S. G. Chaney, and Z. H. Siddik for the gift of the 2008 and 2008C13 cells. A.M. is a recipient of the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer and Fondation pour la Recherche Medicale. This work was supported by a grant from The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center and grants from the National Institutes of Health (P30CA16672-24, 5P50CA83639, and Core Grant CA16672) and the Ovarian Cancer Research Program of the U.S. Department of Defense.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: CDDP, cisplatin [cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II)]; XIAP, X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein; Fas-L, Fas-ligand; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde dehydrogenase.

References

- 1.Loehrer PJ, Einhom LH. Drugs five years later. Cisplatin Annn Intern Med. 1984;100:704–713. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-100-5-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dorr RT, Von Hoff DD. Cancer chemotherapy handbook. 2. Norwalk, CT: Appleton and Lange; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ozols RF. Ovarian cancer, part ii: Treatment. Curr Prob Cancer. 1992;16:61–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parker RJ, Eastman A, Bostick-Bruton F, Reed E. Acquired cisplatin resistance in human ovarian cancer cells is associated with enhanced repair of cisplatin-DNA lesions and reduced drug accumulation. J Clin Invest. 1991;87: 772–777. doi: 10.1172/JCI115080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Makin G, Dive C. Apoptosis and cancer chemotherapy. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:S22–26. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02124-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herr I, Debatin KM. Cellular stress response and apoptosis in cancer therapy. Blood. 2001;98:2603–2614. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.9.2603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andrews PA, Velury S, Mann SC, Howell SB. Cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II) accumulation in sensitive and resistant human ovarian carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 1988;48:68–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Claret FX, Hibi M, Dhut S, Toda T, Karin M. A new group of conserved coactivators that increase the specificity of AP-1 transcription factors. Nature. 1996;383:453–457. doi: 10.1038/383453a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mansouri A, Gaou I, De Kerguenec C, Amsellem S, Haouzi D, Berson A, Moreau A, Feldmann G, Letteron P, Pessayre D, Fromenty B. An alcoholic binge causes massive degradation of hepatic mitochondrial DNA in mice. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:181–190. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70566-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eichhorst ST, Muller M, Li-Weber M, Schulze-Bergkamen H, Angel P, Krammer PH. A novel ap-1 element in the CD95 ligand promoter is required for induction of apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells upon treatment with anticancer drugs. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:7826–7837. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.20.7826-7837.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith ML, Fomace AJ., Jr Mammalian DNA damage-inducible genes associated with growth arrest and apoptosis. Mutat Res. 1996;340:109–124. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1110(96)90043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowe SW, Ruley HE, Jacks T, Housman DE. P53-dependent apoptosis modulates the cytotoxicity of anticancer agents. Cell. 1993;74:957–967. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90719-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferreira CG, Tolis C, Giaccone G. p53 and chemosensitivity. Ann Oncol. 1999;10:1011–1021. doi: 10.1023/a:1008361818480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waldman T, Kinzier KW, Vogelstein B. p2l is necessary for the p53-mediated G1 arrest in human cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1995;55:5187–5190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adams JM, Cory S. The Bcl-2 protein family: Arbiters of cell survival. Science. 1998;281:1322–1326. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gross A, McDonnell JM, Korsmeyer SJ. Bcl-2 family members and the mitochondria in apoptosis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1899–1911. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.15.1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimizu S, Narita M, Tsujimoto Y. Bcl-2 family proteins regulate the release of apoptogenic cytochrome c by the mitochondrial channel VDAC. Nature. 1999;399:483–487. doi: 10.1038/20959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chao DT, Korsmeyer SJ. Bcl-2 family: Regulators of cell death. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:395–419. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Makin G, Hickman JA. Apoptosis and cancer chemotherapy. Cell Tissue Res. 2000;301:143–152. doi: 10.1007/s004419900160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnstone RW, Ruefli AA, Lowe SW. Apoptosis: A link between cancer genetics and chemotherapy. Cell. 2002;108:153–164. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00625-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamesaki S, Kamesaki H, Jorgensen TJ, Tanizawa A, Pommier Y, Cossman J. Bcl-2 protein inhibits etoposide-induced apoptosis through its effects on events subsequent to topoisomerase ii-induced DNA strand breaks and their repair. Cancer Res. 1993;53:4251–4256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu JR, Fletcher B, Page C, Hu C, Nunez G, Baker V. Bcl-xl is expressed in ovarian carcinoma and modulates chemotherapy-induced apoptosis. Gynecol Oncol. 1998;70:398–403. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1998.5125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clem RJ, Miller LK. Control of programmed cell death by the baculovirus genes p35 and iap. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:5212–5222. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.8.5212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deveraux QL, Reed JC. lap family proteins—suppressors of apoptosis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:239–252. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LaCasse EC, Baird S, Komeluk RG, MacKenzie AE. The inhibitors of apoptosis (IAPS) and their emerging role in cancer. Oncogene. 1998;17:3247–3259. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li J, Feng Q, Kim JM, Schneiderman D, Liston P, Li M, Vanderhyden B, Faught W, Fung MF, Senterman M, Komeluk RG, Tsang BK. Human ovarian cancer and cisplatin resistance: Possible role of inhibitor of apoptosis proteins. Endocrinology. 2001;142:370– 380. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.1.7897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tang G, Minemoto Y, Dibling B, Purcell NH, Li Z, Karin M, Lin A. Inhibition of JNK activation through NF-kappaβ target genes. Nature. 2001;414:313–317. doi: 10.1038/35104568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deveraux QL, Roy N, Stennicke HR, Van Arsdale T, Zhou Q, Srinivasula SM, Alnemri ES, Salvesen GS, Reed JC. IAPs block apoptotic events induced by caspase-8 and cytochrome c by direct inhibition of distinct caspases. EMBO J. 1998;17:2215–2223. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.8.2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Friesen C, Herr I, Kranimer PH, Debatin KM. Involvement of the CD95 (apo-1/fas) receptor/ligand system in drug-induced apoptosis in leukemia cells. Nat Med. 1996;2:574–577. doi: 10.1038/nm0596-574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kasibhatla S, Brunner T, Genestier L, Echeverri F, Mahboubi A, Green DR. DNA damaging agents induce expression of fas ligand and subsequent apoptosis in T lymphocytes via the activation of NF-kappaβ and AP-1. Mol Cell. 1998;1:543–551. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Potapova O, Haghighi A, Bost F, Liu C, Birrer MJ, Gjerset R, Mercola D. The jun kinase/stress-activated protein kinase pathway functions to regulate DNA repair and inhibition of the pathway sensitizes tumor cells to cisplatin. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:14041–14044. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.22.14041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanchez-Perez I, Murguia JR, Perona R. Cisplatin induces a persistent activation of jnk that is related to cell death. Oncogene. 1998;16:533–540. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nicholson DW, Ali A, Thomberry NA, Vaillancourt JP, Ding CK, Gallant M, Gareau Y, Griffin PR, Labelle M, Lazebnik YA, et al. Identification and inhibition of the ice/ced-3 protease necessary for mammalian apoptosis. Nature. 1995;376:37–43. doi: 10.1038/376037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Henkels KM, Turchi JJ. Cisplatin-induced apoptosis proceeds by caspase-3-dependent and -independent pathways in cisplatin-resistant and -sensitive human ovarian cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3077–3083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]