Abstract

Objective

Recent studies have shown that angiotensin II (Ang II) plays a critical role in the pathogenesis and progression of hypertensive kidney disease. However, the signaling mechanisms are poorly understood. In this study, we investigated the role of CXCR6 in Ang II-induced renal injury and fibrosis.

Approach and Results

Wild-type and CXCR6-GFP knockin mice were treated with Ang II via subcutaneous osmotic minipumps at 1500 ng/kg/min after unilateral nephrectomy for up to 4 weeks. WT and CXCR6-GFP knockin mice had virtually identical blood pressure at baseline. Ang II treatment led to an increase in blood pressure that was similar between WT and CXCR6-GFP knockin mice. CXCR6-GFP knockin mice were protected from Ang II-induced renal dysfunction, proteinuria, and fibrosis. CXCR6-GFP knockin mice accumulated fewer bone marrow-derived fibroblasts and myofibroblasts and produced less extracellular matrix protein in the kidneys following Ang II treatment. Furthermore, CXCR6-GFP knockin mice exhibited fewer F4/80+ macrophages and CD3+ T cells and expressed less proinflammatory cytokines in the kidneys after Ang II treatment. Finally, wild-type mice engrafted with CXCR6−/− bone marrow cells displayed fewer bone marrow-derived fibroblasts, macrophages, and T cells in the kidney after Ang II treatment compared with wild-type mice engrafted with CXCR6+/+ bone marrow cells.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that CXCR6 plays a pivotal role in the development of Ang II-induced renal injury and fibrosis through regulation of macrophage and T cell infiltration and bone marrow-derived fibroblast accumulation.

Keywords: Chemokine receptor, Angiotensin II, Inflammation, fibrosis

INTRODUCTION

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a growing public health problem in the world. Hypertension is a major cause of CKD. A prominent pathological feature in patients with CKD is inflammation, tubular atrophy, and interstitial fibrosis. The degree of renal fibrosis correlates well with the prognosis of kidney disease1. Renal interstitial fibrosis is characterized by massive fibroblast activation and excessive production and deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM), which leads to the destruction of renal parenchyma and progressive loss of kidney function. The current therapeutic options in the clinical settings for this devastating condition are limited and often ineffective except for dialysis or kidney transplantation, thus making chronic kidney failure one of the most expensive diseases to treat on a per-patient basis2. Despite improvement in the knowledge of diverse aspects related to CKD, the pathogenesis and the initial molecular events leading to chronic renal fibrosis and eventually chronic renal failure remain elusive. Therefore, a better understanding of the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of chronic kidney disease is essential for developing effective strategies to treat this devastating disorder and prevent its progression.

A large body of evidence indicates that activation of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) plays a central role in initiation and progression of CKD through regulation of inflammation and fibrosis3. The underlying mechanisms involved in angiotensin II (Ang II)-induced kidney disease are incompletely understood. Recent studies have shown that inflammatory and immune cell infiltration and altered chemokine production are characteristic for hypertensive kidney damage4, 5. The infiltration of circulating cells into sites of injury is mediated by locally produced chemokines through interaction with their respective receptors. However, the mechanism resulting in infiltration of these cells in hypertension remains incompletely understood.

We have recently shown that CXCL16 is induced in the kidney in response to Ang II and genetic deletion of CXCL16 suppresses Ang II-induced renal injury and fibrosis6. CXCR6 is the receptor for CXCL16, which is expressed in T cells, monocytes, and myeloid fibroblasts7–9. In this study, we investigated the role of CXCR6 in leukocyte recruitment and renal injury in Ang II-induced hypertensive kidney disease.

Materials and Methods

WT C57BL/6 and CXCR6-GFP knockin mice on a C57BL/6 background were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory as described10. Genotyping was confirmed with PCR following the manufacturer’s instruction. Mice were bred and maintained in the animal care facility of Baylor College of Medicine and had access to food and water ad libitum. All animal procedures were in accordance with national and international animal care and ethical guidelines and have been approved by the institutional animal welfare committee. A full description of methods can be found in the online-only Data Supplement.

RESULTS

Blood Pressure

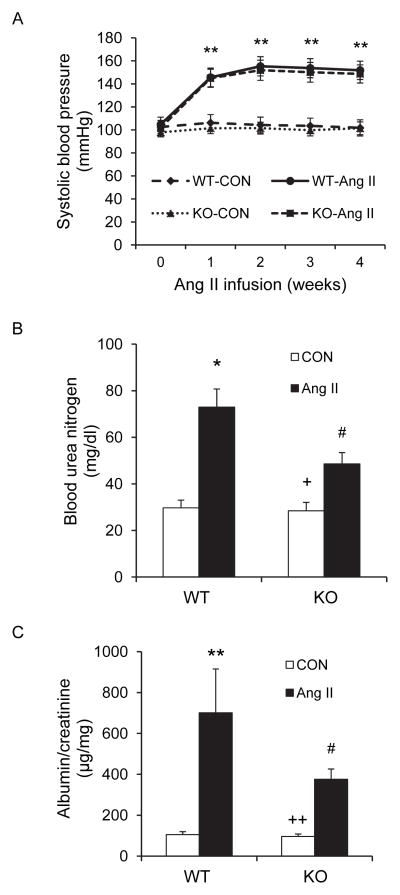

There were no significant differences in blood pressure among the four groups at baseline. Ang II treatment increased blood pressure in both WT and CXCR6-GFP knockin mice with no differences between the two treatment groups (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Effect of CXCR6 disruption on blood pressure, renal function, and proteinuria.

A. Systolic blood pressure was elevated to the similar level between Ang II-treated WT and CXCR6-GFP knockin mice. ** P<0.01 between Ang II-treated groups and vehicle-treated control groups. n=6 per group. B. CXCR6 disruption significantly attenuated Ang II-induced renal dysfunction. * P<0.05 vs WT controls; + P < 0.05 vs KO Ang II; and # P < 0.05 vs WT Ang II. n=6 per group. C. CXCR6 disruption inhibited Ang II-induced albuminuria. ** P<0.01 vs WT controls; ++ P < 0.01 vs KO Ang II; and # P < 0.05 vs WT Ang II. n=6 per group.

Renal Function

Treatment with Ang II for 4 weeks caused kidney dysfunction in WT mice as reflected by significant elevation of blood urea nitrogen (BUN). Kidney function was preserved in CXCR6-GFP knockin mice with BUN markedly lower than WT mice (Figure 1B).

Albuminuria

WT mice developed massive albuminuria after Ang II treatment for 4 weeks, whereas Ang II-treated CXCR6-GFP knockin mice produced significantly less albuminuria (Figure 1C).

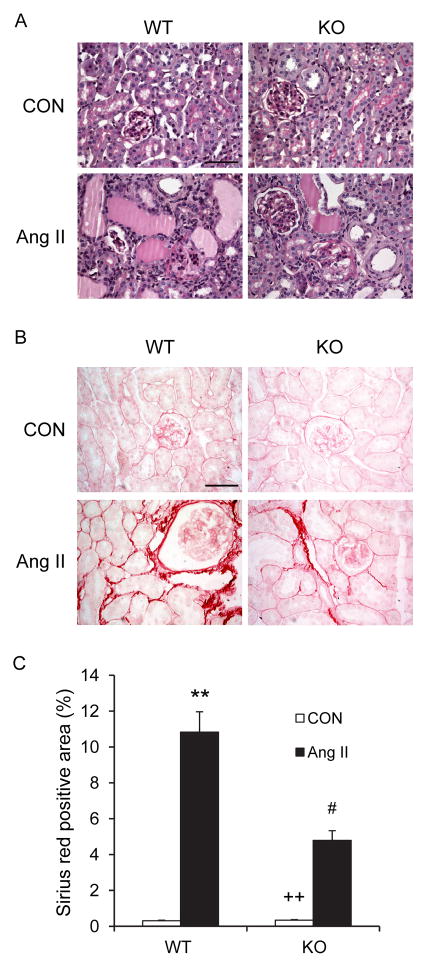

Kidney Injury and Fibrosis

To assess the effect of CXCR6 disruption on Ang II-induced kidney damage, kidney sections were stained with PAS and scored for histological injury after 4 weeks of saline or Ang II infusion (Figure 2A and Table I in the online-only Data Supplement). On a semiquantitative scale that includes glomerulosclerosis, interstitial disease, fibrosis, and vascular injury, the 2 saline-infused groups had minimal kidney damage. Ang II caused a marked increase in the severity of kidney injury in the WT mice, which was substantially reduced in CXCR6-GFP knockin mice. Sirius red staining showed that Ang II-treated WT mice developed significant collagen deposition in the kidney compared with saline-treated WT mice. These fibrotic responses were significantly reduced in CXCR6-GFP knockin mice with chronic Ang II infusion (Figure 2B–C).

Figure 2. Effect of CXCR6 disruption on renal injury and fibrosis.

A. Representative photomicrographs of PAS stained sections showing Ang II-induced kidney damage in WT and CXCR6-GFP knockin mice. Scale bar: 50 μm. B. Representative photomicrographs of kidney sections from WT and CXCR6-GFP knockin mice 4 weeks after Ang II or saline treatment stained with Sirius red for assessment of total collagen deposition. Scale bar: 50 μm. C. Quantitative analysis of interstitial collagen content in the kidneys. ** P < 0.01 vs WT controls, ++ P < 0.01 vs KO Ang II, and # P < 0.05 vs WT Ang II. n= 6 per group.

We next examined the effect of CXCR6 disruption on the expression of collagen I and fibronectin, two major components of ECM. Immunofluorescence staining demonstrated that CXCR6 disruption attenuated the upregulation of collagen I (Figure 3A–B) and fibronectin (Figure 3C–D). Similar results were obtained with Western blot analysis (Figure 3E–F).

Figure 3. Effect of CXCR6 disruption on fibronectin and collagen I expression.

A. Representative photomicrographs of fibronectin immunofluorescence staining in the kidneys of WT and CXCR6-GFP knockin mice 4 weeks after Ang II or saline treatment. Scale bar: 25 μm. B. Quantitative analysis of fibronectin positive area in the kidneys. ** P <0.01 vs WT controls, + P <0.05 vs KO Ang II, and # P <0.05 vs WT Ang II. n=6 per group. C. Representative photomicrographs of collagen I immunofluorescence staining in the kidneys of WT and CXCR6-GFP knockin mice 4 weeks after Ang II or saline treatment. Scale bar: 25 μm. D. Quantitative analysis of collagen I positive area in the kidneys. ** P <0.01 vs WT controls, + P <0.05 vs KO Ang II, and # P <0.05 vs WT Ang II. n=6 per group. E. Representative Western blots show the protein levels of fibronectin and collagen I in the kidneys of WT and CXCR6-GFP knockin mice 4 weeks after Ang II or saline treatment. F. Western blot analysis of fibronectin and collagen I protein expression in the kidneys of WT and CXCR6-GFP knockin mice. * P < 0.05 vs WT controls, + P < 0.05 vs KO Ang II, and # P < 0.05 vs WT Ang II. n=5 per group.

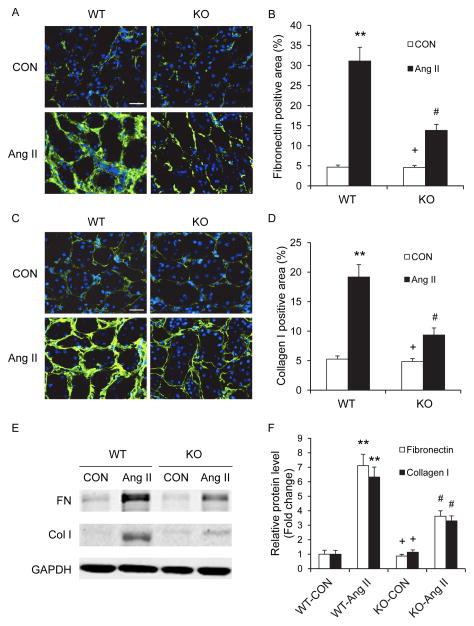

Myeloid Fibroblasts Accumulation and Myofibroblast Formation

Recent evidence indicates that myeloid fibroblasts contribute significantly to the pathogenesis of renal fibrosis and circulating fibroblast precursors expressed CXCR69, 11–14. To examine the effect of CXCR6 disruption on the accumulation of myeloid fibroblasts in the kidney, WT and CXCR6-GFP knockin mice were infused with vehicle or Ang II for 2 weeks. The two-week model of Ang II infusion was chosen because we and others have shown that cellular infiltration precedes the development of target organ injury9, 15, 16. Kidney sections were stained for CD45 and procollagen I and examined with a fluorescence microscope. The number of bone marrow-derived fibroblasts dual positive for CD45 and procollagen I was significantly reduced in the kidneys of Ang II-treated CXCR6-GFP knockin mice compared with WT mice (Figure 4A–B). These data indicate that CXCR6 has an important role in recruiting bone marrow-derived fibroblasts into the kidney in response to Ang II.

Figure 4. CXCR6 disruption suppresses bone marrow-derived fibroblast accumulation and myofibroblast formation in the kidney.

A. Representative photomicrographs of kidney sections from WT and CXCR6-GFP knockin mice 2 weeks after Ang II or saline treatment stained for CD45 (red), procollagen I (green), and DAPI (blue). Arrow heads indicate CD45 and procollagen I double positive fibroblasts. Scale bar: 25 μm. B. Quantitative analysis of CD45+ and procollagen I+ fibroblasts in kidneys of WT and CXCR6-GFP knockin mice 2 weeks after Ang II or saline treatment. ** P < 0.01 vs WT controls, + P < 0.05 vs KO Ang II, and # P < 0.05 vs WT Ang II. n=6 per group. C. Representative photomicrographs of α-SMA immunofluorescence staining in kidneys of WT and CXCR6-GFP knockin mice 4 weeks after Ang II or saline treatment. Scale bar: 25 μm. D. Quantitative analysis of α-SMA positive area in kidneys. ** P <0.01 vs WT controls, ++ P <0.01 vs KO Ang II, and # P <0.05 vs WT Ang II. n=6 per group. E. Representative Western blots show the levels of α-SMA protein expression in the kidneys of WT and CXCR6-GFP knockin mice 4 weeks after Ang II or saline treatment. F. Quantitative analysis of α-SMA protein expression in the kidneys. ** P <0.01 vs WT controls, + P <0.05 vs KO Ang II, and # P <0.05 vs WT Ang II. n=5 per group.

To determine if CXCR6 disruption influences myofibroblast formation, kidney sections were stained for α-SMA, a marker of myofibroblasts, and examined with a fluorescence microscope. Ang II-treated CXCR6-GFP knockin mice exhibited a significant reduction in the number of α-SMA+ myofibroblasts in the kidneys compared with Ang II-treated WT mice (Figure 4C–D). Consistent with these findings, Western blot analysis showed that disruption of CXCR6 significantly reduced the protein expression levels of α-SMA in the kidneys after Ang II treatment compared with WT mice (Figure 4E–F).

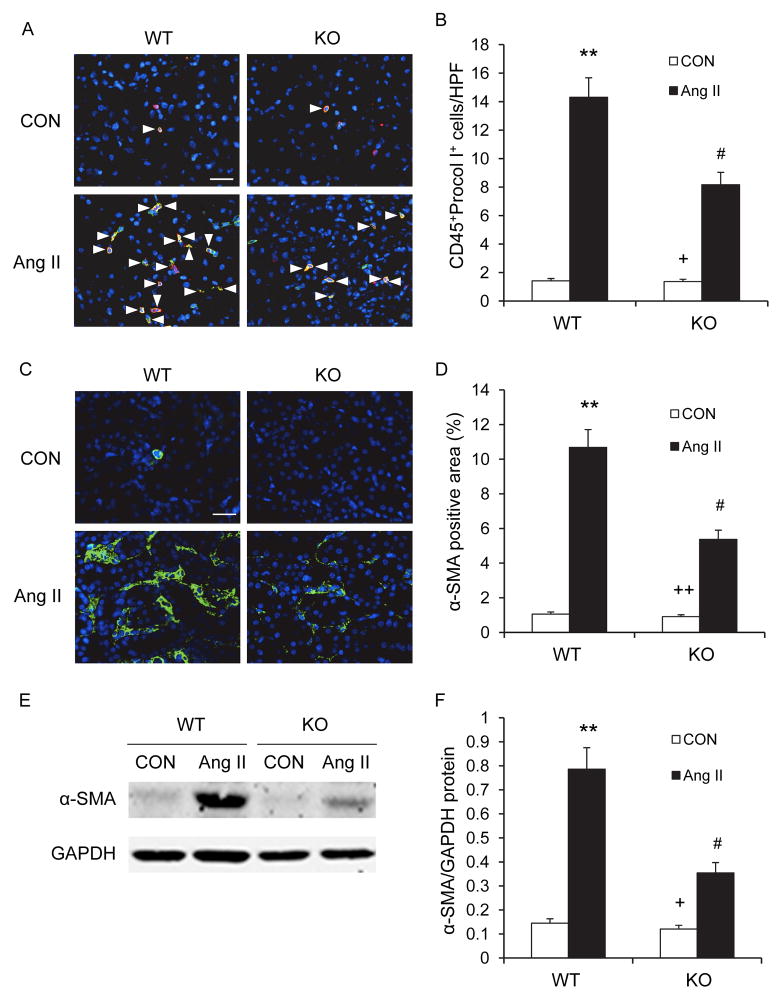

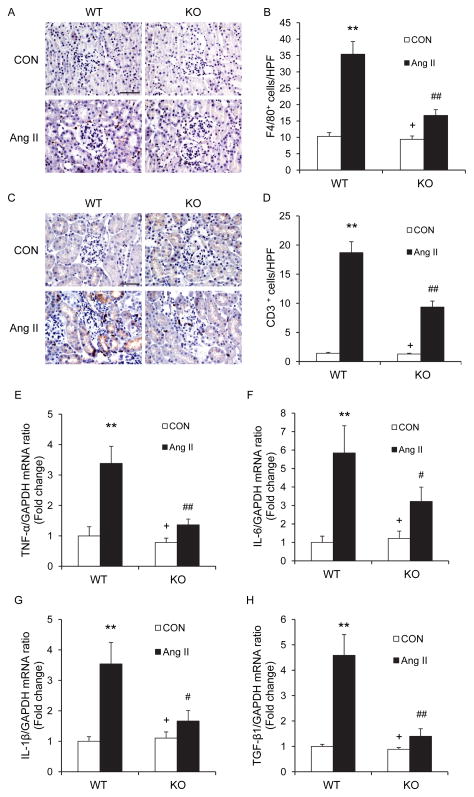

Macrophage and T cell Infiltration and Inflammatory Cytokine Production

Recent evidence indicates that macrophages and T cells play a critical role in the pathogenesis of Ang II-induced target organ damage17. We examined if infiltrating macrophages and T cells in the kidney express CXCR6. Kidney sections were stained for CXCR6 and F4/80, a macrophage marker, or CD3, a T cell marker. The results showed that infiltrating F4/80+ macrophages and CD3+ T cells express CXCR6 (Figure I in the online-only Data Supplement). To determine if CXCR6 plays a role in the regulation of inflammatory cell infiltration into the kidney, WT and CXCR6-GFP knockin mice were infused with vehicle or Ang II for 2 weeks. Kidney sections were stained for F4/80 and CD3. Significant infiltration of macrophages and T cells was observed in the kidneys of WT mice after Ang II treatment compared with the vehicle-treated control group. In contrast, disruption of CXCR6 significantly inhibited macrophage and T cell infiltration into the kidneys after Ang II treatment (Figure 5A–D). These results indicate that CXCR6 mediates inflammatory cell infiltration into the kidney in Ang II-induced hypertensive kidney disease.

Figure 5. CXCR6 disruption reduces Ang II-induced inflammation.

A. Representative photomicrographs of kidney sections stained for F4/80 (a macrophage marker) (brown) and counterstained with hematoxylin (blue) in WT and CXCR6-GFP knockin mice 2 weeks after Ang II or saline treatment. Scale bar: 50 μm. B. Quantitative analysis of F4/80+ macrophages in the kidneys. **P < 0.01 vs WT controls; ## P < 0.01 vs WT Ang II; + P < 0.05 vs KO Ang II. n=6 in each group. C. Representative photomicrographs of kidney sections stained for CD3 (a T lymphocyte marker) (brown) and counterstained with hematoxylin (blue) in WT and CXCR6-GFP knockin mice 2 weeks after Ang II or saline treatment. Scale bar: 50 μm. D. Quantitative analysis of CD3+ T cells in the kidneys. **P < 0.01 vs WT controls; ## P < 0.01 vs WT Ang II; + P < 0.05 vs KO Ang II. n=6 in each group. E. Quantitative analysis of TNF-α mRNA expression in the kidneys. **P < 0.01 vs WT controls; ## P < 0.01 vs WT Ang II; + P < 0.05 vs KO Ang II. n=5 in each group. F. Quantitative analysis of IL-6 mRNA expression in the kidneys. **P < 0.01 vs WT control; # P < 0.05 vs WT Ang II; + P < 0.05 vs KO Ang II. n=5 in each group. G. Quantitative analysis of IL-1β mRNA expression in the kidneys. **P < 0.01 vs WT control; # P < 0.05 vs WT Ang II; + P < 0.05 vs KO Ang II. n=5 in each group. H. Quantitative analysis of TGF-β1 mRNA expression in the kidneys. **P < 0.01 vs WT controls; ## P < 0.01 vs WT Ang II; + P < 0.05 vs KO Ang II. n=5 in each group.

We next examined the effect of CXCR6 disruption on the expression of known pro-inflammatory cytokines that are involved in the pathogenesis of kidney injury 18. The mRNA levels of IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, and TGF-β1 were increased significantly in the kidneys of WT mice after Ang II treatment (Figure 5E–H). In contrast, the upregulation of IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, and TGF-β1 was greatly attenuated in the kidneys of CXCR6-GFP knockin mice after Ang II treatment (Figure 5E–H).

Effect of CXCR6 Disruption on Mobilization of Myeloid Fibroblasts Precursors, Monocytes, and T cells

To determine the effect of CXCR6 disruption on mobilization of monocytes, and T cells and fibroblast precursors, peripheral nucleated cells were stained for CD11b and CD3 or CD45 and collagen I from WT and CXCR6-GFP knockin mice two weeks after saline or Ang II treatment. Our results showed that there were no significant differences among the four groups though Ang II treatment led to a small, but not significant increase in monocytes, T cells, and fibroblast precursors (Figure II in the online-only Data Supplement).

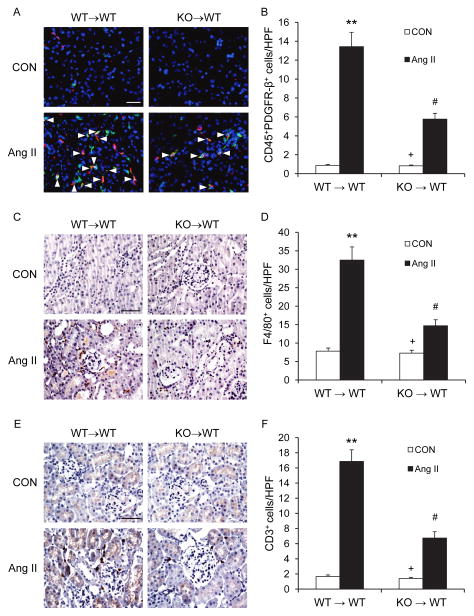

Effect of CXCR6 Disruption in Bone Marrow Cells on Accumulation of Myeloid Fibroblasts, Macrophages, and T cells in the Kidney

To further examine the role of CXCR6 in bone marrow-derived cells in recruiting myeloid fibroblasts, macrophages, and T cells, we performed bone marrow chimera experiments by reconstitution of WT mice with CXCR6+/+ or CXCR6−/− bone marrow cells. Eight weeks after bone marrow transplantation, chimeric mice were subjected to vehicle or Ang II treatment for 2 weeks. The genotype of bone marrow-derived cells from the chimeric mice was confirmed by PCR of DNA extracted from peripheral blood cells (Figure III in the online-only Data Supplement). Compared with WT mice transplanted with CXCR6+/+ bone marrow cells, WT mice transplanted with CXCR6−/− bone marrow cells accumulated fewer CD45+ and PDGFR-β+ fibroblasts, F4/80+ macrophages, and CD3+ T cells (Figure 6). These data indicate that CXCR6 in bone marrow-derived cells is critical for recruiting bone marrow-derived fibroblasts, macrophages, and T cells into the kidney in response to Ang II.

Figure 6. CXCR6 disruption in bone marrow-derived cells inhibits myeloid fibroblast, macrophage, and T cell infiltration into the kidney.

A. Representative photomicrographs of kidney sections stained for CD45 (red), PDGFR-β (green), and DAPI (blue). Arrow heads indicate CD45 and PDGFR-β double positive fibroblasts. Scale bar: 25 μm. B. Quantitative analysis of CD45 and PDGFR-β+ fibroblasts in kidneys. ** P < 0.01 vs WT controls, + P < 0.05 vs KO Ang II, and # P < 0.05 vs WT Ang II. n=5 per group. C. Representative photomicrographs of kidney sections from WT mice transplanted with CXCR6+/+ or CXCR6−/nus; bone marrow cells 2 weeks after Ang II or saline treatment stained for F4/80 (brown) and counterstained with hematoxylin (blue). Scale bar: 50 μm. D. Quantitative analysis of F4/80+ macrophages in the kidneys. **P < 0.01 vs WT controls; # P < 0.05 vs WT Ang II; + P < 0.05 vs KO Ang II. n=5 in each group. E. Representative photomicrographs of kidney sections stained for CD3 (brown) and counterstained with hematoxylin (blue). Scale bar: 50 μm. F. Quantitative analysis of CD3+ T cells in the kidneys. **P < 0.01 vs WT controls; # P < 0.05 vs WT Ang II; +P < 0.05 vs KO Ang II. n=5 in each group.

Discussion

In this study, we have demonstrated that disruption of CXCR6 leads to renal protection in an experimental model of hypertensive kidney disease induced by Ang II. In the Ang II-induced hypertension model, disruption of CXCR6 preserves renal function, reduces urinary albumin excretion, and attenuates tubulointerstitial disease, glomerular injury, and vascular damage.

A large body of evidence indicates that activation of RAS plays a central role in the initiation and progression of chronic kidney disease. The underlying mechanisms involved in Ang II-induced hypertensive kidney disease are incompletely understood. Recent studies have shown that inflammatory and immune cell infiltration are characteristic for hypertensive kidney disease4, 5. The infiltration of circulating cells into sites in injury is mediated by locally produced chemokines through interaction with their respective receptors. We have recently shown that CXCL16 is induced in the kidney in response to Ang II and CXCL16 deficiency suppresses Ang II-induced renal inflammation and fibrosis6. The CXCL16 receptor, CXCR6, is expressed in T cells, monocytes, and myeloid fibroblasts7–9. In the present study, we have demonstrated that CXCR6 is pathologically important in recruitment of myeloid fibroblasts, macrophages, and T cells and development of renal injury and fibrosis because disruption of CXCR6 inhibits recruitment of bone marrow-derived fibroblasts, macrophages, and T cells into the kidney and the development of renal interstitial fibrosis in response to Ang II treatment. Furthermore, compared with WT mice transplanted with CXCR6+/+ bone marrow cells, WT mice transplanted with CXCR6−/− bone marrow cells accumulate fewer myeloid fibroblasts, macrophages, and T cells into the kidney. These data provide compelling evidence for a critical role of CXCR6 in recruiting myeloid fibroblasts, macrophages, and T cells into the kidney and pathogenesis of renal injury and fibrosis. Of note, CXCL16 knockout mice and CXCR6-GFP knockin displayed similar phenotype in response to Ang II treatment.

A novel finding of this study is the striking reduction in Ang II-induced renal fibrosis in CXCR6-GFP knockin mice. Renal fibrosis is a final common pathway leading to renal failure. Because activated fibroblasts are the principal effector cells that are responsible for ECM production in the fibrotic kidney, their activation is regarded as a key event in the pathogenesis of renal fibrosis19, 20. However, the origin of these fibroblasts remains debatable. They are traditionally thought to arise from resident renal fibroblasts21–23. Recent evidence suggests they may originate from bone marrow-derived fibroblast precursors9, 11–14, 24–26. We and others have shown that these cells migrate into the kidney in response to obstructive injury and contribute to the development of renal fibrosis9, 12, 25–28. However, the signaling mechanisms underlying the recruitment of these bone marrow-derived fibroblast precursors into the kidney are incompletely understood. In the present study, we showed that disruption of CXCR6 inhibits bone marrow-derived fibroblast accumulation and myofibroblast formation in the kidney and the development of renal fibrosis in response to Ang II. These results indicate that CXCR6 plays a key role in recruitment of bone marrow-derived fibroblasts into the kidney and development of renal fibrosis in Ang II-induced hypertensive nephropathy.

Macrophages and T cells have been shown to play an important role in the development of hypertensive kidney disease17. Ang II is a key factor in the regulation of inflammatory response in hypertensive end organ damage3, 29. CXCR6 is expressed in various leukocyte subsets including monocytes and T cells7–9. Recent studies have shown that CXCR6 plays an important role in inflammatory disease such as atherosclerosis30. In the present study, our results show that Ang II-induced interstitial infiltration of macrophages and T cells into the kidney is significantly attenuated in CXCR6-GFP knockin mice. These data indicate that CXCR6 signaling mediates Ang II-induced macrophage and T cell infiltration.

Our results indicate that disruption of CXCR6 significantly attenuate proinflammatory and profibrotic cytokine expression in the kidney in response to Ang II. This is relevant because proinflammatory cytokines – TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β have been implicated in the pathogenesis of Ang II-induced target organ damage31 and TGF-β1 functions as a downstream mediator of Ang II-induced renal fibrosis3, 32.

In summary, our studies identify that CXCR6 critically regulates Ang II-induced renal injury and fibrosis. In response to Ang II, the activated CXCR6 signaling recruits myeloid fibroblasts, monocytes/macrophages, and T cells into the kidney leading to proinflammatory and profibrotic cytokine production, renal injury, and fibrosis. These findings suggest that inhibition of CXCR6 signaling could constitute a novel therapeutic target for hypertensive kidney disease.

Supplementary Material

Significance.

Our study defines a critical role of CXCR6 in regulating Ang II-induced renal injury and fibrosis. In response to Ang II, the activated CXCR6 signaling recruits myeloid fibroblasts, monocytes/macrophages, and T cells into the kidney leading to proinflammatory and profibrotic cytokine production, renal injury, and fibrosis. These findings suggest that inhibition of CXCR6 signaling could constitute a novel therapeutic strategy for hypertensive kidney disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. JoAnn Trial for critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank Joel M. Sederstrom for his expert assistance with the flow cytometry.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants - K08HL092958 and R01DK095835 and an American Heart Association grant 11BGIA7840054 (to YW). J Yan was supported in part by a NIH/NIDDK T32 training grant –T32DK62706. ML Entman was supported by a NIH grant – R01HL089792. The Cytometry and Cell Sorting Core at Baylor College of Medicine was supported by NIH grants - AI036211, CA125123, and RR024574.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

References

- 1.Nath KA. The tubulointerstitium in progressive renal disease. Kidney Int. 1998;54:992–994. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bidani AK, Griffin KA. Pathophysiology of hypertensive renal damage: Implications for therapy. Hypertension. 2004;44:595–601. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000145180.38707.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruiz-Ortega M, Ruperez M, Esteban V, Rodriguez-Vita J, Sanchez-Lopez E, Carvajal G, Egido J. Angiotensin ii: A key factor in the inflammatory and fibrotic response in kidney diseases. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:16–20. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfi265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crowley SD, Frey CW, Gould SK, Griffiths R, Ruiz P, Burchette JL, Howell DN, Makhanova N, Yan M, Kim HS, Tharaux PL, Coffman TM. Stimulation of lymphocyte responses by angiotensin ii promotes kidney injury in hypertension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;295:F515–524. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00527.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guzik TJ, Hoch NE, Brown KA, McCann LA, Rahman A, Dikalov S, Goronzy J, Weyand C, Harrison DG. Role of the t cell in the genesis of angiotensin ii induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2449–2460. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xia Y, Entman ML, Wang Y. Critical role of cxcl16 in hypertensive kidney injury and fibrosis. Hypertension. 2013;62:1129–1137. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim CH, Kunkel EJ, Boisvert J, Johnston B, Campbell JJ, Genovese MC, Greenberg HB, Butcher EC. Bonzo/cxcr6 expression defines type 1-polarized t-cell subsets with extralymphoid tissue homing potential. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:595–601. doi: 10.1172/JCI11902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sato T, Thorlacius H, Johnston B, Staton TL, Xiang W, Littman DR, Butcher EC. Role for cxcr6 in recruitment of activated cd8+ lymphocytes to inflamed liver. J Immunol. 2005;174:277–283. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.1.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen G, Lin SC, Chen J, He L, Dong F, Xu J, Han S, Du J, Entman ML, Wang Y. Cxcl16 recruits bone marrow-derived fibroblast precursors in renal fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:1876–1886. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010080881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Unutmaz D, Xiang W, Sunshine MJ, Campbell J, Butcher E, Littman DR. The primate lentiviral receptor bonzo/strl33 is coordinately regulated with ccr5 and its expression pattern is conserved between human and mouse. J Immunol. 2000;165:3284–3292. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.3284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li J, Deane JA, Campanale NV, Bertram JF, Ricardo SD. The contribution of bone marrow-derived cells to the development of renal interstitial fibrosis. Stem Cells. 2007;25:697–706. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sakai N, Wada T, Yokoyama H, Lipp M, Ueha S, Matsushima K, Kaneko S. Secondary lymphoid tissue chemokine (slc/ccl21)/ccr7 signaling regulates fibrocytes in renal fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:14098–14103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511200103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grimm PC, Nickerson P, Jeffery J, Savani RC, Gough J, McKenna RM, Stern E, Rush DN. Neointimal and tubulointerstitial infiltration by recipient mesenchymal cells in chronic renal-allograft rejection. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:93–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107123450203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broekema M, Harmsen MC, van Luyn MJ, Koerts JA, Petersen AH, van Kooten TG, van Goor H, Navis G, Popa ER. Bone marrow-derived myofibroblasts contribute to the renal interstitial myofibroblast population and produce procollagen i after ischemia/reperfusion in rats. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:165–175. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005070730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haudek SB, Cheng J, Du J, Wang Y, Hermosillo-Rodriguez J, Trial J, Taffet GE, Entman ML. Monocytic fibroblast precursors mediate fibrosis in angiotensin-ii-induced cardiac hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;49:499–507. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sopel M, Falkenham A, Oxner A, Ma I, Lee TD, Legare JF. Fibroblast progenitor cells are recruited into the myocardium prior to the development of myocardial fibrosis. International journal of experimental pathology. 2012;93:115–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2011.00797.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luft FC, Dechend R, Muller DN. Immune mechanisms in angiotensin ii-induced target-organ damage. Ann Med. 2012;44 (Suppl 1):S49–54. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2011.653396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung AC, Lan HY. Chemokines in renal injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:802–809. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010050510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neilson EG. Mechanisms of disease: Fibroblasts--a new look at an old problem. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2006;2:101–108. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strutz F, Muller GA. Renal fibrosis and the origin of the renal fibroblast. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:3368–3370. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Picard N, Baum O, Vogetseder A, Kaissling B, Le Hir M. Origin of renal myofibroblasts in the model of unilateral ureter obstruction in the rat. Histochem Cell Biol. 2008;130:141–155. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0433-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qi W, Chen X, Poronnik P, Pollock CA. The renal cortical fibroblast in renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Powell DW, Mifflin RC, Valentich JD, Crowe SE, Saada JI, West AB. Myofibroblasts. I. Paracrine cells important in health and disease. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:C1–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.277.1.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iwano M, Plieth D, Danoff TM, Xue C, Okada H, Neilson EG. Evidence that fibroblasts derive from epithelium during tissue fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:341–350. doi: 10.1172/JCI15518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xia Y, Entman ML, Wang Y. Ccr2 regulates the uptake of bone marrow-derived fibroblasts in renal fibrosis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77493. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang J, Lin SC, Chen G, He L, Hu Z, Chan L, Trial J, Entman ML, Wang Y. Adiponectin promotes monocyte-to-fibroblast transition in renal fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:1644–1659. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013030217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Niedermeier M, Reich B, Rodriguez Gomez M, Denzel A, Schmidbauer K, Gobel N, Talke Y, Schweda F, Mack M. Cd4+ t cells control the differentiation of gr1+ monocytes into fibrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:17892–17897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906070106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang J, Chen J, Yan J, Zhang L, Chen G, He L, Wang Y. Effect of interleukin 6 deficiency on renal interstitial fibrosis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e52415. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mann DL. Angiotensin ii as an inflammatory mediator: Evolving concepts in the role of the renin angiotensin system in the failing heart. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2002;16:7–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1015355112501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galkina E, Harry BL, Ludwig A, Liehn EA, Sanders JM, Bruce A, Weber C, Ley K. Cxcr6 promotes atherosclerosis by supporting t-cell homing, interferon-gamma production, and macrophage accumulation in the aortic wall. Circulation. 2007;116:1801–1811. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.678474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mehta PK, Griendling KK. Angiotensin ii cell signaling: Physiological and pathological effects in the cardiovascular system. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C82–97. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00287.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolf G. Renal injury due to renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system activation of the transforming growth factor-beta pathway. Kidney Int. 2006;70:1914–1919. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.