Abstract

Early life stress has been linked to the etiology of mental health disorders. Rodent models of neonatal maternal separation stress frequently have been used to explore the long-term effects of early stress on changes in affective and cognitive behaviors. However, most current paradigms risk metabolic deprivation, due to prolonged periods of pup removal from the dam. We have developed a new paradigm in Balb/CByJ mice, that combines very brief periods of maternal separation with temperature stress to avoid the confound of nutritional deficiencies. We have also included a within-litter control group of pups that are not removed from the dam. The present experiments provide an initial behavioral characterization of this new model. We show that neonatally stressed mice display increased anxiety and aggression along with increased locomotion but decreased exploratory behavior. In contrast, littermate controls show increased exploration of novelty, compared to age-matched, colony reared controls. Behavioral changes in our briefly stressed mice substantially concur with the existing literature, except that we were unable to observe any cognitive deficits in our paradigm. However, we show that within litter control pups also sustain behavioral changes suggesting complex and long lasting interactions between different environmental factors in early postnatal life.

Keywords: Neonatal Stress, Anxiety, Aggression, Contextual Fear Conditioning

Introduction

Early life stress has been implicated in mental health disorders, such as schizophrenia, clinical depression and more recently, Autism Spectrum Disorder (Anisman & Zacharko, 1982; de Kloet, Joels, & Holsboer, 2005; Heim & Nemeroff, 1999; Juul-Dam, Townsend, & Courchesne, 2001; Kinney, Munir, Crowley, & Miller, 2008; McEwen, 2004). Maternal separation has frequently been used in rodents to model neonatal stress and has been well characterized in terms of its developmental programming of the HPA axes and associated behavioral alterations (Anisman, Zaharia, Meaney, & Merali, 1998; Champagne, de Kloet, & Joels, 2009; Lehmann & Feldon, 2000; Levine, 2005; Meaney, 2001). The most frequently employed procedure involves removal of the pups from the dam for intervals of three to six hours, for a two to three week duration, following birth (Kaffman & Meaney, 2007; Sanchez, Ladd, & Plotsky, 2001) introducing the possibility of substantial metabolic deprivation, associated with prolonged maternal separation (Schmidt, Levine, Alam, Harbich, Sterlemann, Ganea, de Kloet, Holsboer, & Muller, 2006; Suchecki, Rosenfeld, & Levine, 1993; van Oers, de Kloet, Whelan, & Levine, 1998).

The objective of this study is to provide an initial behavioral characterization of a new stress paradigm in Balb/CByJ mice, which minimizes maternal separation time from the pups. Our long-term goal is to study the effects of neonatal stress on cortical development. Malnutrition is a substantial confound in regards to brain development (Resnick, Miller, Forbes, Hall, Kemper, Bronzino, & Morgane, 1979). Thus, in the current paradigm, we have reduced the maternal separation time to one hour/day. We also have limited stress exposure to the first postnatal week, since this time window represents the most dynamic and plastic period in the development of somatosensory cortex (Berger-Sweeney & Hohmann, 1997). To insure, nevertheless, a sufficient stress effect in our mice, we have combined maternal separation with short exposures to cold stress, which has previously shown to be a very effective stressor (Avishai-Eliner, Yi, Newth, & Baram, 1995; Odeon, Salatino, Rodriguez, Scolari, & Acosta 2010; Yi & Baram, 1994). We chose Balb/CByJ mice for this paradigm because of their high stress responsiveness (Brinks, van der Mark, de Kloet, & Oitzl, 2007; Ducottet & Belzung, 2004; Shanks & Anisman, 1988) as well as high potential for developmental plasticity (Chapillon, Manneche, Belzung, & Caston, 1999; Priebe, Brake, Romeo, Sisti, Mueller, McEwen, & Francis, 2006; Zaharia, Kulczycki, Shanks, Meaney, & Anisman, 1996). We have chosen to include a within-litter control group (LMC) by subjecting only half of each litter to maternal separation/temperature stress while the other half of the pups remained with the dam. This approach was aimed at factoring out maternal effects on offspring behavior in adulthood Kaffman & Meaney, 2007; Meaney, 2001; Zaharia, Kulczycki, Shanks, Meaney & Anisman, 1996).

Neonatal maternal separation/isolation paradigms are characterized, typically, by increased anxiety responses on tasks such as the elevated plus maze and/or open field crossing (Brinks, van der Mark, de Kloet, & Oitzl, 2007; Kalinichev, Easterling, Plotsky, & Holtzman, 2002b; Knuth & Etgen, 2007; Lehmann, Pryce, Bettschen, & Feldon, 1999; Romeo, Mueller, Sisti, Ogawa, McEwen, & Brake, 2003; Troakes & Ingram, 2009; Wei, David, Duman, Anisman, & Kaffman 2010; Wigger & Neuman, 1999). Mild to moderate cognitive deficits, on task such as the Morris water maze and object recognition, have frequently been described (Aisa, Tordera, Lasheras, Del Rio, & Ramirez, 2008; Huot, Plotsky, Lenox, & McNamara, 2002; Kosten, Karanian, Yeh, Haile, Kim, Kehoe, & Bahr, 2007; Lehmann, Pryce, Bettschen, & Feldon, 1999) as have changes in novelty responses and locomotion (Kalinichev, Easterling, & Holtzman, 2002a; Slotten, Kalinichev, Hagan, Marsden, & Fone, 2006; Ogawa, Mikuni, Kuroda, Muneoka, Mori, & Takahashi, 1994) albeit not always in the same direction. Freezing, as an indicator of acquisition of contextual fear conditioning (CCFC), was affected in some studies (Kosten, Lee, & Kim, 2006; Stevenson, Spicer, Mason, & Marsden, 2009; Lehmann, Pryce, Bettschen, & Feldon, 1999) but not others (Kosten, Miserendino, Bombace, Lee, & Kim, 2005; Wilber, Southwood, & Wellman, 2009). In addition, neonatal maternal separation stress can increase male aggression (Veenema, Blume, Niederle, Buwalda, & Neumann, 2006; Veenema & Neumann, 2009). Divergence in behavioral observations between different labs and studies has generally been attributed to differences in the extent of the stress experience or variance in the genetic backgrounds of the rodents employed or both (Lehmann & Feldon, 2000, Zaharia, et al. 1996). Maternal care effects are also an established factor in altering adult behavioral responses (Kaffman & Meaney, 2007; Meaney, 2001, Zaharia, et al. 1996).

For an initial behavioral characterization of our new paradigm, we here have chosen to assess behavioral domains, previously show to be affected in the neonatal stress literature. Since Balb/CByJ mice require very extensive training to perform adequately on spatial learning and memory tasks such as e.g. the Morris water maze (Arters, Hohmann, Mills, Olaghere, & Berger-Sweeney, 1998), we chose an Open Field Object Recognition task, adapted by us for use in this mouse strain, to assess spatial learning/memory. This task has the added benefit of lending itself simultaneously, to the assessment of locomotion, anxiety and novelty response in mice.

Materials and Methods

All studies were performed on offspring of Balb/CByJ mice purchased from Jackson Laboratories and raised in our own breeding colony at Morgan State University. Mice were housed in clear polycarbonate cages in temperature- and humidity-controlled rooms with a timed 12 light-/dark cycle, in accordance with to the guidelines of the American Association of Veterinary Medicine. Mice were behaviorally tested during the light portion of the light-dark cycle. All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Morgan State University and carried out in accordance with NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the guidelines of the American Veterinary association.

Neonatal stress exposure and experimental design

Male and female Balb/CByJ pups were subjected to maternal separation for one hour daily between postnatal days [PND] two and seven. Pups were removed for stress exposure late morning, during the light cycle. We employed a split litter design, removing half the male and female pups daily, for 6 days, from the dam for one hour (STR group); the other half of the litter remained with the dam (LMC group). STR vs. LMC pups were marked by toe clip (digit 5, STR bilaterally, LMC digit 5 unilaterally). In addition, STR and LMC pups were marked with non-toxic paint on their backs during the first postnatal week, for easier identification of STR mice for daily removals. During the stress procedure, pups were exposed, on alternating days, to 30 min. of hot (37 degree C°) or cold stress (5 degree C°), allowed to re-acclimatize to room temperature for 30 minutes and then returned to the dam in the home cage. Following the stress exposure, pups remained with the dam until PND 30, when they were weaned. At weaning, mice were separated by sex, and group housed according to their litters of origin. Additional litters, born during the same time period as the STR/LMC mice, were used as age-matched, colony reared, controls (AMC). With the exception of weekly cage changes, which did not commence until the pups were one week old, these mice were not handled at all until weaning. Mice began behavioral testing at three month of age.

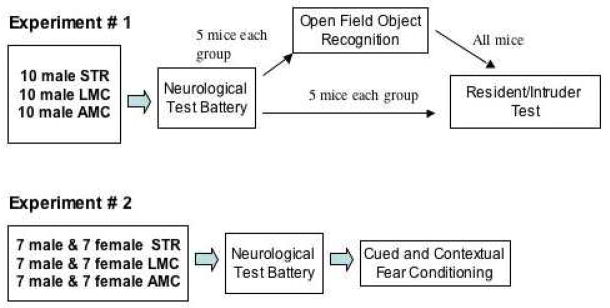

The mice used for the studies reported here were generated in two separate cohorts, designated below as “Experiment # 1” and “Experiment # 2”. STR/LMC and AMC mice respectively, originated from at least four different litters in each cohort. Table 1, below, illustrates the specific design used for each experiment.

Table 1.

Design diagram

|

Behavioral Assessment

At three months of age all mice assigned were first subjected to a neurological test battery as previously described (Hohmann, Walker, Boylan, & Blue, 2007; Picker, Yang, Ricceri, & Berger-Sweeney, 2006). Briefly, we assessed coordination, balance and strength by monitoring the mice’ righting response, grip strength and balance on crossing a thin, long rod towards the home cage. Mice were scored with the examiner blind to treatment group. All tests were performed in triplicate and average scores for each animal were used for analysis. This neurological testing took approximately one hour/mouse and also served as “handling” exposure for the mice, acquainting them to the individual conducting their subsequent behavioral testing. The Open Field Object Recognition task was performed within one week following the neurological test battery, as previously described by us in (Hohmann et al., 2007; Krasnova, Betts, Dada, Jefferson, Ladenheim, Becker, Cadet, & Hohmann, 2007). This task has been adapted from the procedure used by Ricceri and colleagues (Ricceri, Usiello, Valanzano, Calamandrei, Frick, & Berger-Sweeney, 1999) and is performed in a round enclosure of approximately three feet diameter. A detailed description, including diagrams, is presented in (Hohmann et al., 2007). On the first session [S1] mice are placed into the enclosure without objects and this session is used to assess locomotor activity, by measuring quadrant crossing, and thigmotaxis, as indicator of anxiety by measuring time spend in the center vs. periphery of the enclosure. During sessions 2–4 [S2–S4], five objects of different shapes and colors were placed at set locations in the enclosure. In session 5 [S5] two of the objects are moved to a new location (displaced objects), where they remain for session 6, and in session 7 [S7], a novel, substituted object is introduced in place of one present in all prior sessions; the rest of the objects remain in position (Non substituted objects). Mice are placed into the enclosure for 6 minutes with 3-minute intervals between sessions during which odor cues are wiped away with 75% ethanol solution.

Time spent with each object is recorded. Spatial learning/memory is assessed in session 5, by calculating time spent with the displaced objects, minus time spent with the same objects in session 4 (before they were moved). This is compared to time spent with the non-displaced objects in session 5 minus time spent with the same objects in session 4. Novelty response is assessed in session 7 by calculating time spent with the novel object, minus time spent with the object previously in this location; this is compared to time spent with the “old”, non-substituted four objects in session 7 minus time spent with the same objects in session 6.

Mice were videotaped during the performance of the Open Field Object Recognition task and data were analyzed on a Dell Pentium computer using Observer Video-Pro (Noldus) software. Statistical analysis was performed using factorial and repeated measures ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc tests (GraphPad Prizm).

Aggression was studied using a modified “resident intruder” task (Crawley, 2000). Briefly, mice were tested, a) directly after the neurological test battery, at 3 month, or b) one week later, after conclusion of testing in the Open Field Object Recognition paradigm. The resident adult, male mouse (STR, LMC or AMC) was placed within a large cage (“16.5” L, “8.5” D, “8” H) alone, for 10 minutes. After ten minutes, a normal male Balb/CByJ intruder mouse of the same age was added into the rat cage, but protected within a wire mesh container of approximately 6 inches in diameter. The resident mouse’ response to the intruder mouse was observed for 15 minutes. The experiment was videotaped and quantification of aggressive behaviors (nipping, tail rattling, lunging, biting of the wire mesh) were made using the Pheno Scan Suite, Top Scan 1.0 from CleverSys.Inc.. The individual analyzing the videotapes was blind to the condition of the mice observed. Statistical analysis was performed using Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric analysis with Dunn post hoc test (GraphPad Prizm).

Cued and Contextual Fear Conditioning was conducted according to Crawley (Crawley, 2000) with some minor modifications and utilizing TSE, custom build, Fear Conditioning equipment. Freezing was scored via computerized assessment and validated by visual examination of the videotaped sessions. Briefly, on day 1, mice were placed into chamber A, with a metal floor that can be electrified. An auditory conditioning stimulus (white noise, 80 dB) was combined with a mild foot-shock of 0.035 mA, for 2 seconds, as conditioning stimulus. The number of seconds spent freezing (total immobility except for respiration) was measured, per unit time, as an indicator of the fear response, at initial entry into the chamber and past each of two tone/conditioning shock pairings. Twenty-four hours later (day 2), the same mouse was placed into chamber B, with a different sensory context (e.g. smell (vanilla), shape, floor texture) and freezing behavior was scored prior to and after application of the auditory conditioning stimulus. On day 3, the mouse was returned to the original conditioning environment (chamber A) for 5 minutes, to measure the freezing response again. The amount of freezing, prior to the conditioning tone stimulus, on day 2 in chamber B compared to freezing on day 3 in chamber A is regarded as a measure of context learning. A measure of cued conditioning is regarded as the amount of freezing in environment B prior to and after exposure to the conditioning (tone) stimulus. Statistical analysis was performed using factorial and repeated measures ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc tests (GraphPad Prizm).

Statistical Analysis

Individual statistical approaches are listed above, for each method.

Results

Experiment #1: Effects of neonatal stress and rearing conditions on anxiety, exploratory behavior and aggression

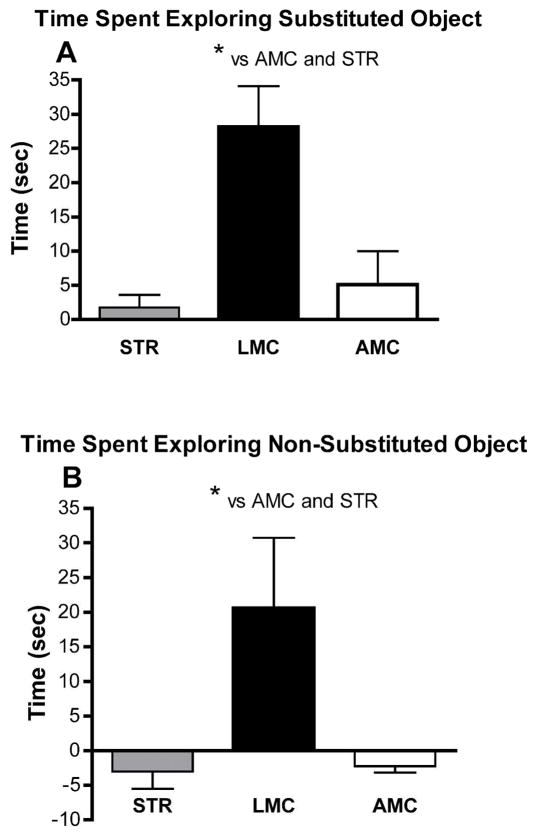

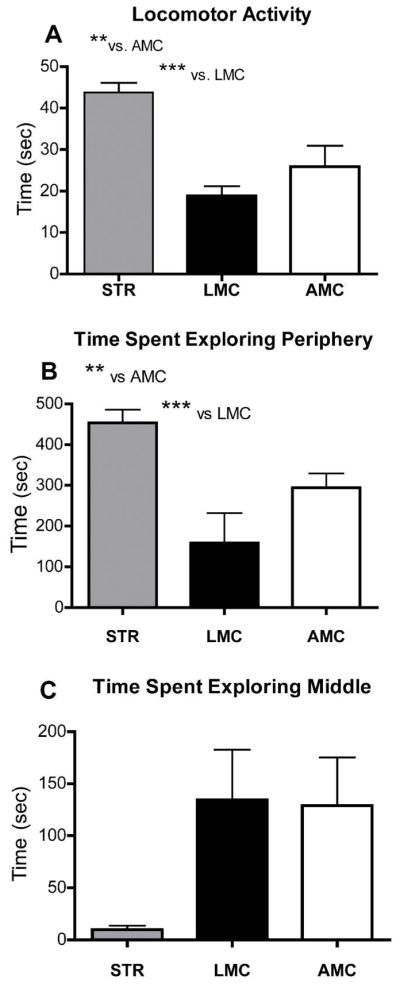

1.1. Ten each, male STR, LMC and yoked AMC mice were assessed in the neurological test battery, followed by Open Field Object Recognition testing. ANOVA main effects for condition (STR, LMC, AMC) were significant for locomotor activity (P< 0.001, F=13.7, DF29) in the empty enclosure. Post hoc analysis, as illustrated in Figure 1A, revealed that STR males had significantly higher locomotor activity then AMC and LMC, while LMC mice did not differ significantly from AMC. In addition, STR males also spent significantly more time in the periphery and significantly less time in the center of the empty enclosure, resulting in main effects of (P=0.0015, F=8.4, DF29) and (P=0.051, F=3.3, DF29) respectively (see Figure 1B&C). There were no significant differences between the groups, in responses to the displaced objects in session 5. All groups showed slightly increased exploration of the displaced over the non-displaced objects, indicating that they had acquired the spatial arrangements of the objects and noticed object displacement. However, repeated measures ANOVA revealed significantly differences between the groups in exploratory activity in sessions 2 through 7 (P=0.006, F= 8.96, DF17). This was due, predominantly, to significantly decreased exploratory activity in STR compared to AMC males (post hoc P<0.01). Significant one-way, factorial ANOVA differences also emerged in the exploration of the substituted and non-substituted objects in session 7. As shown in Figure 2, a significant main effect was seen for exploration of both, the substituted, novel object (P=0.015, F=9.8, DF29), as well as for the non-substituted objects in session 7, compared to session 6 (P=0.018, F=4.9, DF29). This was due, clearly, to substantially increased exploration of all objects by LMC mice in session 7. STR as AMC mice, on the other hand displayed the same normal behavioral pattern of moderately increased exploration of the novel, substituted object, at the expense of exploration of the old, non-substituted objects.

FIGURE 1.

Locomotor and exploratory activity in the empty enclosure, used for Open Field Object Recognition testing (session 1). ** denotes P< 0.01 and *** denotes P< 0.001 in Tukey’s post-hoc analyses (A, B), highly significant main effects are detailed in the text. Locomotor activity in the male STR mice was substantially elevated above AMC and LMC. STR mice also displayed a significant level of thigmotaxis, spending substantially more time in the periphery then the center of the open enclosure then AMC or LMC. LMC mice did not differ significantly from AMC in any of these parameters.

FIGURE 2.

This figure illustrates differential exploration of objects between session 7 and session 6 in the Open Field Object Recognition task. In A, differences in time exploring the substituted object vs. the object previously in the same position are shown and in B, differences between exploration of the other four, non-substituted objects is compared between sessions 7 and 6. Positive numbers mean that exploration was increased in session 7 over session 6 and negative numbers indicate that there was a decrease of exploration of the objects in session 7 over session 6. As expected for normal mice, AMC males presented with increased exploration of the (substituted) novel object and slightly decreased exploration of all other objects. STR mice did not significantly differ from AMC mice. However, LMC males displayed significantly (P<0.05 post hoc) increased levels of exploration, compared to both, STR or AMC males, for all objects (substituted and non-substituted) in session 7. Please see the text for ANOVA main effects.

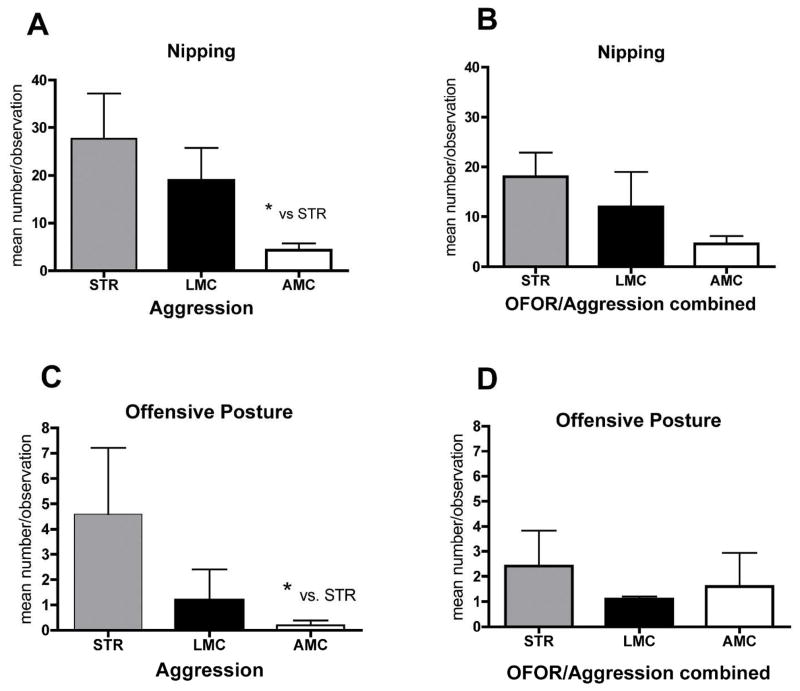

1.2. A modified Resident/Intruder test was performed with half of the males in each group tested in the Open Field Object Recognition task, above, and in addition, with an additional five/each STR, LMC and AMC males, tested directly, without prior Open Field Object Recognition testing. Analysis of the aggression data showed alterations in both the STR and LMC mice, compared to AMC. Subsequent, separate analysis of these two cohorts of mice, with and without prior testing in the Open Field Object Recognition task, revealed, that the extent of the aggressive display was modulated by previous behavioral experience of the mice. Aggression in both STR and LMC was attenuated compared to AMC, if the mice had been exposed to Open Field Object Recognition testing prior to the resident intruder paradigm, but the effects were more pronounced in STR mice. We chose a Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric analysis with Dunn post hoc analysis for these data, because of the presence of outliers in each group, suggesting a non-Gaussian distribution of the data. Nipping at the intruder in behaviorally naïve mice showed a significant main effect (P=0.03, Kruskal-Wallis stats 6.99, groups 3), which was no longer evident in mice with prior Open Field Object Recognition testing (compare Fig. 3A and B). Similarly, mice directly tested in the Resident/Intruder test showed significantly elevated aggression (P=0.02, Kruskal-Wallis stats 7.6, groups 3) in offensive posturing, but mice with prior Open Field Object Recognition testing no longer displayed significant differences in aggressive displays (Fig. 3C and D). On the other hand, wall climbing/rearing, an escape/exploratory and not an aggressive behavior, did not show significant differences between the groups (P=0.50, Kruskal-Wallis stats 1.4, group 3).

FIGURE 3.

Assessment of aggressive displays in males either tested directly (A, C) in the Resident/Intruder test, or following Open Field Object Recognition testing. Significant main effects for A and C are reported in the text. Note, that significant differences in nipping and offensive posture display were due mostly to the STR mice (* denotes post-hoc differences at P< 0.05) compared to AMC, when tested only in the resident intruder paradigm.

Experiment # 2: Effects of neonatal stress and rearing conditions on cued/contextual fear behavior

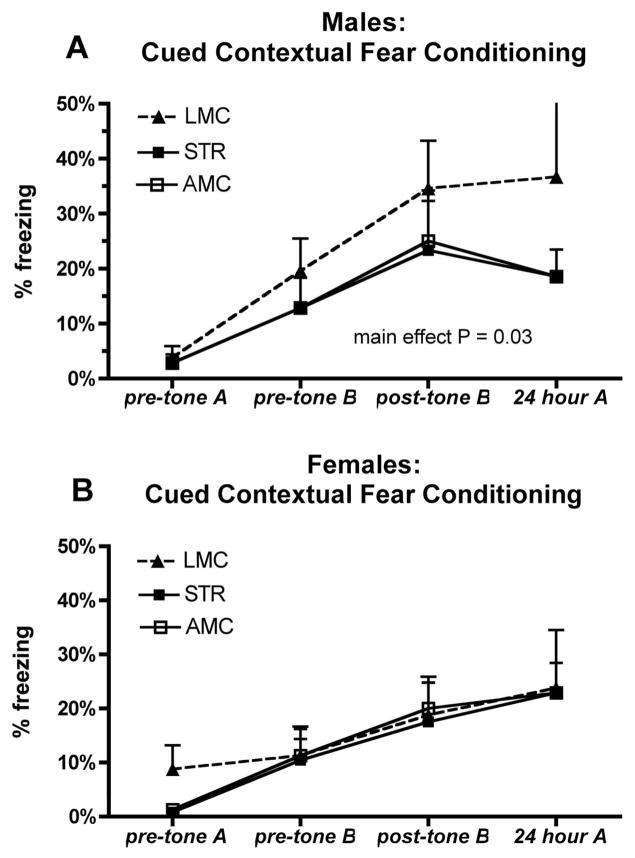

Based on the earlier observations of increased thigmotaxis in STR mice, compared to LMC and AMC, we prepared a cohort of 7 each, STR, LMC and AMC male and female mice, for testing on a Cued and Contextual Fear Conditioning paradigm. The inclusion of females in this particular task was motivated by prior (unpublished) observations in our lab, that Balb/CByJ male and female mice may have a different response to both the conditioning and the contextual stimuli compared to male mice of the same strain.

Male and female STR, LMC and AMC mice acquired the cued response, as indicated by increased freezing following the sound cue in the novel environment B, and also displayed appropriate context recognition, as indicated by diminished freezing in the novel environment (B) compared to the original conditioning environment (A) (see Figure 4). Repeated measures ANOVA, for males and females analyzed together, showed a significant main effect of (P= 0.018, F 3.87, DF23); Tukey’s post-hoc analysis revealed that this significance was carried by differences (P < 0.05) between LMC males and AMC and STR and females. No significant differences between AMC or STR males and females were seen in this analysis. When we followed up on this observation by conducting separate repeated measure ANOVAs for males and females, significant differences emerged within males (P= 0.034, F= 6.2, DF11), with LMC males displaying overall the most freezing of any group (P <0.05 compared to STR in Tukey’s post-hoc). No significant differences were present between females (P= 0.07, F =4.16, DF11) analyzed separately.

FIGURE 4.

Fear behavior, as assessed in the Cued and Contextual Fear Conditioning task. The amount of freezing is show under the following conditions: initial day 1, pre-conditioning, environment A, on day 2 (pre-tone environment B) and following exposure to the tone cue (post-tone B), 24 hours later, when re-exposed to the initial conditioning environment (24 hour A). No significant differences were seen for female mice between the STR, LMC and AMC groups but repeated measures ANOVA showed significantly increased freezing in LMC males.

Discussion

We here describe a novel neonatal stress protocol that can induce specific, long-term behavioral changes without inducing any gross neurological abnormalities in stressed mice. This stress paradigm exposes pups to only one hour/day of removal from maternal care and lactation and thus is consistent with our goal to devise a paradigm free of the confound of metabolic deprivation.

The significant behavioral changes we describe here for STR mice, as adults, are largely consistent with behavioral observations previously reported for more extensive neonatal maternal separation procedures. Surprisingly, compared to mice from normal, colony-raised litters (AMC), within liter controls, LMC mice, also displayed behavioral changes in adulthood. There are fundamental differences between the behavioral changes in STR and LMC mice, but there is also a small area of overlap (see Table 1 for summary). Thus, in addition to validating the present model of brief maternal separation as appropriate for future morphological studies on neonatal stress effects, this study has provided evidence, that environmental factors, other then the intended stressor, may permanently disrupt behavior and potentially brain morphology and in mice.

Increased anxiety has been the most consistently observed behavioral results of early stress effects (Brinks et al., 2009; Kalinichev et al., 2002b; Knuth & Etgen, 2007; Romeo et al., 2003; Troakes & Ingram, 2009; Wei et al.; Wigger & Neuman, 1999). Thus, our finding of increased thigmotaxis in the open field (see Fig. 1) is consistent with previous observations. Likewise, increased aggression as described by us for STR, and to some smaller extent LMC mice, in the Resident/Intruder task has precedence that has been linked to increased anxiety as well as to long-term alterations in HPA responsiveness, following early stress exposure (Veenema et al., 2006, Veenema & Neumann, 2007; Veenema & Neumann, 2009). Although we did not assess HPA responsiveness in our present study, such behavioral similarities between our model and previous studies suggest that the STR mice in the current study also may have altered stress responsiveness in adulthood.

Increased locomotor activity, as shown in our STR males in the open field, has also been described previously (Kalinichev et al., 2002a; Slotten et al., 2006). On the other hand, STR males showed decreased object exploration in the open field, an observation similar to “behavioral inhibition” reported by Kaneko and colleagues in isolation reared pups (Kaneko, Riley & Ehlers 1996). In light of increased locomotion in our STR mice, the slight decrease in overall object exploration in STR mice is most easily interpreted as a reticence to explore the objects and therefore an anxiety related response. Interestingly, LMC males increased their novelty responsiveness in the absence of altered locomotor activity or decreased anxiety, when compared to AMC mice. Such behavior might be interpreted as increased “risk seeking” but in light of the increased freezing behavior that LMC mice display in the Cued and Contextual Fear Conditioning Paradigm, it is more difficult to interpret.

In contrast to many previous studies of neonatal maternal separation stress, we have been unable to observe altered cognitive performance in our STR mice. This is likely not a methodological issue, since both the Open Field Object Recognition and the Cued and Contextual Fear Conditioning task have been successfully used to detect cognitive changes in models of developmental manipulations (Crawley, 2000; Ricceri, Colozza, & Calamandrei, 2000; Ricceri, Hohmann, & Berger-Sweeney, 2002). Thus, our data suggest, that long-term learning and memory deficits are not an inevitable consequence of early stress exposure. The extent of learning and memory changes described by others (Brinks et al., 2009; Kalinichev et al., 2002b; Knuth & Etgen, 2007; Romeo et al., 2003; Troakes & Ingram, 2009; Wei et al.; Wigger & Neuman, 1999), may well be related to the timing of the stress exposure and its differential effects on different brain regions, but could also have resulted from metabolic consequences of the prolonged maternal separation. In our paradigm, stress was limited to the first postnatal week, a time we targeted to affect neocortical morphogenesis, but when a substantial hippocampal impairment is less likely to occur. Compared to neocortex, the protracted maturation of the hippocampal formation (Altman & Bayer, 1990; Bayer, 1980; Bayer & Altman, 1987) renders it more vulnerable to later postnatal insults.

An unexpected observation we have made here is that the behavioral testing sequence affected the outcome of aggression measurements in the Resident/Intruder task. Our data show an attenuation of aggressive behavioral displays in STR mice in the Resident/Intruder test, after being exposed to the Open Filed Object Recognition task. Such attenuation of aggression was substantial in STR present to a smaller extent in LMC mice but not evident at all in AMC mice. It is interesting to speculate, that, if levels of aggressive display are correlated with acute HPA responsiveness, as consequence of early postnatal programming (Anisman et al. 1998; Veenema & Neumann, 2007), the Open Filed Object Recognition task might have increased the animal’s habituation to the testing environment and/or handler and therewith lowered “the pre-programmed”, subsequent HPA spike (Anisman & Zacharko 1982, Levine 2005) in the resident/intruder test. This is an intriguing questions, with potential significance to the understanding and treatment of stress related mental health conditions and an area of research that we intent to follow up on in future studies.

A novel observation in this study is that the littermates (LMC) in our split litter design also displayd behavioral alterations. In fact, some of the behaviors previously reported, subsequent to maternal separation stress, in single litter protocols (Kalinichev et al., 2002a; Kosten et al., 2006; Kosten et al., 2005; Ogawa et al., 1994) have segregated in our study. Only STR mice displayed significant elevations in anxiety and locomotion, yet, in the Cued and Contextual Fear Conditioning task, LMC, not STR males showed an elevated freezing response. This suggest, that LMC mice may experience some level of stress as well, perhaps as consequence of nest disruption and/or maternal care changes. Previous research has given ample evidence that maternal care behavior is a significant regulator of pup behavior in correlation to HPA programming by adulthood and neonatal stress effects have been argued to result from changes in maternal care behavior, following extended separation from the pups (Kaffman & Meaney, 2007; Levine 2005; Meaney, 2001; Priebe et al. 2006; Weaver, Cervoni, Champagne, D’Alessio, Sharma, Seckl, Dymov, Szyf, & Meaney, 2004, Zaharia, et al. 1996). It has been generally assumed that maternal behavior, if altered, would affect the entire litter equally. However, recent evidence is beginning to argue against this concept (Oitzl, Champagne, van der Veen, & de Kloet, 2009). We are currently in the process of evaluation maternal nursing, licking and grooming behavior in our paradigm.

The observation that STR and LMC mice display, largely, non-overlapping behavioral phenotypes may suggest, that stress related, developmental behavioral disruptions do not occur on a continuous gradient. If confirmed, this could have important implications for understanding the relationship between early stress and the different endophenotypes seen in connection with stress related mental health disorders (Anisman & Zacharko, 1982; de Kloet, Joels, & Holsboer, 2005; Heim & Nemeroff, 1999; Juul-Dam, Townsend, & Courchesne, 2001; Kinney, Munir, Crowley, & Miller, 2008; McEwen, 2004). Since we did not include animals for behaviorally naïve baseline measurements, we have not been able to assess corticosterone levels for this study but in our companion paper we show significant elevations of corticosterone in STR compared to LMC mice as juveniles (see: Hohmann et al. under review). We do not know, as of yet, if corticosteroid levels in LMC mice are also elevated above AMC levels. Future, more detailed studies of corticosterone levels throughout development and in response to an adult re-stress challenge, will help us to better understand this issue. Relevant studies are currently ongoing in our lab.

In conclusion, these behavioral data indicate that we have succeeded in generating a neonatal stress paradigm to pursue our long term goal, to study the effects of stress on cortical ontogenesis and morphology and how such changes may be related to the trajectories of specific, clinically relevant behaviors. Moreover, our split litter design has provided us, in the form of the LMC mice, with the ability to differentiate between consequences of maternal separation/temperature stress versus environmental effects other then the intended stressor. In our companion paper we present an initial morphological characterization on this novel neonatal stress paradigm.

Supplementary Material

Overall exploratory activity in the Open Field Object Recognition task, in STR, LMC and AMC males. Repeated measures ANOVA shows a significant main effect for group differences. Post-hoc analysis shows significantly decreased exploratory activity in STR compared to AMC males (post hoc P<0.01).

TABLE 2.

This table provides an overview of the behavioral modalities affected in STR vs. LMC mice respectively, as compared to AMC. Note that STR mice display increased locomotor activity but decreased exploratory behavior and increased anxiety in the Open Field Object Recognition test. STR males are also significantly more aggressive in the Resident/Intruder task. In contrast, LMC mice show increased exploratory activity when faced with novelty but also increase their amount of freezing in the Cued and Contextual Fear Conditioning paradigm. The only overlap between the LMC and STR phenotype is in regards to increased aggression. Also note, neither STR nor LMC mice show deficits in the learning and memory components of the Open Field Object Recognition or Cued and Contextual Fear Conditioning tasks.

| Locomotor (Open Field) | Exploratory (OFOR) | Anxiety (Open Field) | Novelty (OFOR) | Fear/Freezing (CCFC) | Aggression (Resident/Intruder) | Cognitive (OFOR, CCFC) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STR | ⇧ | ⇩ | ⇧ | ⬄ | ⬄ | ⇧ | ⬄ |

| LMC | ⬄ | ⬄ | ⬄ | ⇧ | ⇧ | ⇧ trend | ⬄ |

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Miss Diana Lipscomb and Miss Kristen Washington for their help in some early aspects of this work. The research was supported by SO6GM51971 to Dr. Christine Hohmann and R25GM058904 training support to MSU undergraduate student N. Beard.

Contributor Information

Christine F. Hohmann, Email: Christine.hohmann@morgan.edu, Department of Biology, Morgan State University, 1700 East Cold Spring Lane, Baltimore MD 21251.

Amber Hodges, Department of Psychology, Morgan State University, 1700 East Cold Spring Lane, Baltimore MD 21251

Miss Nakia Beard, Undergraduate student in the Biology Department at Morgan State University when she conducted the work in this manuscript.

Mr. Justin Aneni, Biology majors at Morgan State University at the time this work was conducted

References

- Aisa B, Tordera R, Lasheras B, Del Rio J, Ramirez MJ. Effects of maternal separation on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses, cognition and vulnerability to stress in adult female rats. Neuroscience. 2008;154(4):1218–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman J, Bayer SA. Prolonged sojourn of developing pyramidal cells in the intermediate zone of the hippocampus and their settling in the stratum pyramidale. J Comp Neurol. 1990;301(3):343–364. doi: 10.1002/cne.903010303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anisman H, Zacharko RM. Depression, the predisposing influence of stress. The Behav and Brain Sciences. 1982;5:89–137. [Google Scholar]

- Anisman H, Zaharia MD, Meaney MJ, Merali Z. Do early life events permanently alter behavioral and hormonal responses to stressors? Int J Devel Neurosci. 1998;16(3–4):149–164. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(98)00025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arter J, Hohmann CF, Mills J, Olaghere O, Berger-Sweeney J. Sexually dimorphic responses to neonatal basal forebrain lesions in mice: I. Behavior and neurochemistry. J Neurobiol. 1998;37(4):582–594. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(199812)37:4<582::aid-neu7>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avishai-Eliner S, Yi SJ, Newth CJL, Baram TZ. Effects of maternal and sibling deprivation on basal and stress induced hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal components in the infant rat. Neurosci Letters. 1995;192:49–52. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11606-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer SA. Development of the hippocampal region in the rat. II. Morphogenesis during embryonic and early postnatal life. J Comp Neurol. 1980;190(1):115–134. doi: 10.1002/cne.901900108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer SA, Altman J. Directions in neurogenic gradients and patterns of anatomical connections in the telencephalon. Prog in Neurobiol. 1987;29:57–106. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(87)90015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger-Sweeney J, Hohmann CF. Behavioral consequences of abnormal cortical development: insights into developmental disabilities. Behav Brain Res. 1997;86:121–142. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(96)02251-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinks V, de Kloet ER, Oitzl MS. Corticosterone facilitates extinction of fear memory in BALB/c mice but strengthens cue related fear in C57BL/6 mice. Exp Neurol. 2009;216(2):375–382. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinks V, van der Mark M, de Kloet R, Oitzl M. Emotion and Cognition in High and Low Stress Sensitive Mouse Strains: A Combined Neuroendocrine and Behavioral Study in BALB/c and C57BL/6J Mice. Front Behav Neurosci. 2007;1:8. doi: 10.3389/neuro.08.008.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne DL, de Kloet ER, Joels M. Fundamental aspects of the impact of glucocorticoids on the (immature) brain. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;14(3):136–142. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawley J. What’s wrong with my mouse? Behavioral phenotyping of transgenic and knock-out mice. New York: Wiley-Liss; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- de Kloet ER, Joels M, Holsboer F. Stress and the brain: from adaptation to disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6(6):463–475. doi: 10.1038/nrn1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducottet C, Belzung C. Behaviour in the elevated plus-maze predicts coping after subchronic mild stress in mice. Physiol Behav. 2004;81(3):417–426. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Nemeroff CB. The impact of early adverse experiences on brain systems involved in the pathophysiology of anxiety and affective disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46(11):1509–1522. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00224-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohmann CF, Walker EM, Boylan CB, Blue ME. Neonatal serotonin depletion alters behavioral responses to spatial change and novelty. Brain Res. 2007;1139:163–177. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.12.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huot RL, Plotsky PM, Lenox RH, McNamara RK. Neonatal maternal separation reduces hippocampal mossy fiber density in adult Long Evans rats. Brain Res. 2002;950(1–2):52–63. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02985-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juul-Dam N, Townsend J, Courchesne E. Prenatal, perinatal, and neonatal factors in autism, pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified, and the general population. Pediatrics. 2001;107(4):E63. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.4.e63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaffman A, Meaney MJ. Neurodevelopmental sequelae of postnatal maternal care in rodents: clinical and research implications of molecular insights. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48(3–4):224–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinichev M, Easterling KW, Holtzman SG. Early neonatal experience of Long-Evans rats results in long-lasting changes in reactivity to a novel environment and morphine-induced sensitization and tolerance. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002a;27(4):518–533. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00326-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinichev M, Easterling KW, Plotsky PM, Holtzman SG. Long-lasting changes in stress-induced corticosterone response and anxiety-like behaviors as a consequence of neonatal maternal separation in Long-Evans rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002b;73(1):131–140. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00781-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko WM, Riley EP, Ehlers CL. Effects of artificial rearing on electrophysiology and behavior in adult rats. Depress Anxiety. 1996;4(6):279–288. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6394(1996)4:6<279::AID-DA4>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney DK, Munir KM, Crowley DJ, Miller AM. Prenatal stress and risk for autism. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32(8):1519–1532. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knuth ED, Etgen AM. Long-term behavioral consequences of brief, repeated neonatal isolation. Brain Res. 2007;1128(1):139–147. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.10.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TA, Karanian DA, Yeh J, Haile CN, Kim JJ, Kehoe P, et al. Memory impairments and hippocampal modifications in adult rats with neonatal isolation stress experience. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2007;88(2):167–176. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TA, Lee HJ, Kim JJ. Early life stress impairs fear conditioning in adult male and female rats. Brain Res. 2006;1087(1):142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TA, Miserendino MJ, Bombace JC, Lee HJ, Kim JJ. Sex-selective effects of neonatal isolation on fear conditioning and foot shock sensitivity. Behav Brain Res. 2005;157(2):235–244. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasnova IN, Betts ES, Dada A, Jefferson A, Ladenheim B, Becker KG, et al. Neonatal dopamine depletion induces changes in morphogenesis and gene expression in the developing cortex. Neurotox Res. 2007 doi: 10.1007/BF03033390. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann J, Pryce CR, Bettschen D, Feldon J. The maternal separation paradigm and adult emotionality and cognition in male and female Wistar rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;64(4):705–715. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00150-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann J, Feldon J. Long-term biobehavioral effects of maternal separation in the rat: consistent or confusing? Rev Neurosci. 2000;11(4):383–408. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2000.11.4.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine S. Developmental determinants of sensitivity and resistance to stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:939–946. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. Protection and damage from acute and chronic stress: allostasis and allostatic overload and relevance to the pathophysiology of psychiatric disorders. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1032:1–7. doi: 10.1196/annals.1314.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meaney MJ. Maternal care, gene expression and the transmission of individual differences in stress reactivity across generations. Ann Rev Neuroscie. 2001;24:1161–1192. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odeon MM, Salatino AE, Rodriguez CB, Scolari MJ, Acosta GB. The response to postnatal stress: amino acids transporters and PKC activity. Neurochem Res. 2010;35(7):967–975. doi: 10.1007/s11064-010-0153-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa T, Mikuni M, Kuroda Y, Muneoka K, Mori KJ, Takahashi K. Periodic maternal deprivation alters stress response in adult offspring: potentiates the negative feedback regulation of restraint stress-induced adrenocortical response and reduces the frequencies of open field-induced behaviors. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1994;49(4):961–967. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90250-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oitzl MS, Champagne DL, Van der Veen R, De Kloet ER. Brain development under stress: Hypotheses of glucocorticoid actions revisited. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009;34(6):853–866. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picker JD, Yang R, Ricceri L, Berger-Sweeney J. An altered neonatal behavioral phenotype in Mecp2 mutant mice. Neuroreport. 2006;17(5):541–544. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000208995.38695.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priebe K, Brake WG, Romeo RD, Sisti HM, Mueller A, McEwen BS, et al. Maternal influences on adult stress and anxiety-like behavior in C57BL/6J and BALB/CJ mice: A cross-fostering study. Dev Psychobiol. 2006;48(1):95–96. doi: 10.1002/dev.20098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick O, Miller M, Forbes W, Hall R, Kemper T, Bronzino J, et al. Developmental protein malnutrition: influences on the central nervous system of the rat. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1979;3(4):233–246. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(79)90011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricceri L, Colozza C, Calamandrei G. Ontogeny of spatial discrimination in mice: a longitudinal analysis in the modified open-field with objects. Dev Psychobiol. 2000;37(2):109–118. doi: 10.1002/1098-2302(200009)37:2<109::aid-dev6>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricceri L, Hohmann C, Berger-Sweeney J. Early neonatal 192 IgG saporin induces learning impairments and disrupts cortical morphogenesis in rats. Brain Res. 2002;954(2):160–172. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03172-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricceri L, Usiello A, Valanzano A, Calamandrei G, Frick K, Berger-Sweeney J. Neonatal 192 IgG-saporin lesions of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons selectively impair response to spatial novelty in adult rats. Behav Neurosci. 1999;113(6):1204–1215. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.113.6.1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo RD, Mueller A, Sisti HM, Ogawa S, McEwen BS, Brake WG. Anxiety and fear behaviors in adult male and female C57BL/6 mice are modulated by maternal separation. Horm Behav. 2003;43(5):561–567. doi: 10.1016/s0018-506x(03)00063-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez MM, Ladd CO, Plotsky PM. Early adverse experience as a developmental risk factor for later psychopathology: evidence from rodent and primate models. Dev Psychopathol. 2001;13(3):419–449. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401003029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt MV, Levine S, Alam S, Harbich D, Sterlemann V, Ganea K, et al. Metabolic signals modulate hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activation during maternal separation of the neonatal mouse. J Neuroendocrinol. 2006;18(11):865–874. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2006.01482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seckl JR, Meaney MJ. Glucocorticoid programming. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1032:63–84. doi: 10.1196/annals.1314.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanks N, Anisman H. Stressor-provoked behavioral changes in six strains of mice. Behav Neurosci. 1988;102(6):894–905. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.102.6.894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotten HA, Kalinichev M, Hagan JJ, Marsden CA, Fone KC. Long-lasting changes in behavioural and neuroendocrine indices in the rat following neonatal maternal separation: gender-dependent effects. Brain Res. 2006;1097(1):123–132. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.04.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson CW, Spicer CH, Mason R, Marsden CA. Early life programming of fear conditioning and extinction in adult male rats. Behav Brain Res. 2009;205(2):505–510. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchecki D, Rosenfeld P, Levine S. Maternal regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary- adrenal axis in the infant rat: the roles of feeding and stroking. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1993;75(2):185–192. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(93)90022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troakes C, Ingram CD. Anxiety behaviour of the male rat on the elevated plus maze: associated regional increase in c-fos mRNA expression and modulation by early maternal separation. Stress. 2009;12(4):362–369. doi: 10.1080/10253890802506391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Oers HJ, de Kloet ER, Whelan T, Levine S. Maternal deprivation effect on the infant’s neural stress markers is reversed by tactile stimulation and feeding but not by suppressing corticosterone. J Neurosci. 1998;18(23):10171–10179. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-23-10171.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veenema AH, Blume A, Niederle D, Buwalda B, Neumann ID. Effects of early life stress on adult male aggression and hypothalamic vasopressin and serotonin. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24(6):1711–1720. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veenema AH, Neumann ID. Neurobiological mechanisms of aggression and stress coping: a comparative study in mouse and rat selection lines. Brain Behav Evol. 2007;70(4):274–285. doi: 10.1159/000105491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veenema AH, Neumann ID. Maternal separation enhances offensive play-fighting, basal corticosterone and hypothalamic vasopressin mRNA expression in juvenile male rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(3):463–467. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver IC, Cervoni N, Champagne FA, D’Alessio AC, Sharma S, Seckl JR, et al. Epigenetic programming by maternal behavior. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7(8):847–854. doi: 10.1038/nn1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei L, David A, Duman RS, Anisman H, Kaffman A. Early life stress increases anxiety-like behavior in Balbc mice despite a compensatory increase in levels of postnatal maternal care. Horm Behav. 57(4–5):396–404. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigger A, Neuman ID. Periodic maternal deprivation induces gender -dependent alterations in behavioral and enuroendocrine responses to emotional stress in adult rats. Physiol Behav. 1999;66(2):293–302. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(98)00300-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilber AA, Southwood CJ, Wellman CL. Brief neonatal maternal separation alters extinction of conditioned fear and corticolimbic glucocorticoid and NMDA receptor expression in adult rats. Dev Neurobiol. 2009;69(2–3):73–87. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi SJ, Baram T. Corticotropin releasing hormone mediates the response to cold stress in neonatal rat without copensatory enhancement of the peptide’s gene expression. Endocrinology. 1994;135(6):2364–2368. doi: 10.1210/endo.135.6.7988418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaharia MD, Kulczycki J, Shanks N, Meaney MJ, Anisman H. The effects of early postnatal stimulation on Morris water-maze acquisition in adult mice: genetic and maternal factors. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;128(3):227–239. doi: 10.1007/s002130050130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Overall exploratory activity in the Open Field Object Recognition task, in STR, LMC and AMC males. Repeated measures ANOVA shows a significant main effect for group differences. Post-hoc analysis shows significantly decreased exploratory activity in STR compared to AMC males (post hoc P<0.01).