Introduction

The term circadian rhythm (from the latin circa diem, which means ‘for about a day’) was coined by Halberg to describe endogenous oscillations in organisms that were observed in approximate association with the earth's daily rotation cycle1. Circadian rhythms are hypothesized to have evolved in aerobic organisms to anticipate changes of environmental oxygen levels driven by photosynthetic bacteria and the solar cycle2. They present competitive advantages to organisms, by handling energy supply more efficiently and enhancing their ability to survive respiration-associated cycles of oxidative stress. In mammals, it has been estimated that approximately 10% of the genome is under circadian control3, 4.

Over the past fifteen years, evidence for circadian oscillations of components of the immune system has emerged as an integral regulator that has the potential to impact disease onset and therapies5, 6. Recent studies suggest that cyclical recruitment of immune cells to tissues can affect disease. Rhythms in tissues appear to be synchronized globally while acting locally via sympathetic nerves to orchestrate tissue-specific oscillations in the expression of adhesion molecules and chemokines by endothelial cells7. These rhythms are matched by endogenous oscillations in the expression of pro-migratory factors by immune cells, thus increasing the likelihood of their homing to tissues at specific stages in the circadian cycle. Additional data point to the importance of circadian expression of components of the innate immune system for the onset of inflammatory diseases8, 9.

In this article, we review the components of the immune system that have been shown to be oscillating over the course of a day and will discuss the implications of these fluctuations as potential factors in the circadian onset of diseases.

Entrainment of circadian rhythms

In humans, autonomous circadian rhythms span approximately 24h in length and need to be synchronized to overlap with the daily rotational cycle of the earth. The alignment of an organisms’ endogenous circadian rhythm to an external rhythm is called entrainment. The light patterns represent the principal environmental cue or zeitgeber (German for ‘time giver’10) to align the daily oscillations of the organism. Light anchors the organism in its geophysical time by setting the rest–activity cycle. In addition, it is indirectly responsible for the time of food intake, which is itself another powerful entrainer of rhythm11.

The central clock

In opaque organisms such as mammals, light is processed through the eye and is transmitted via the retinohypothalamic tract to suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN) neurons in the hypothalamus12. The SCN are the central clock, the master pacemaker of the organism13. Recent excellent reviews have provided a detailed overview of the molecular components comprising the clock11, 12, 14, 15; the reader is encouraged to consult them as these concepts will only be briefly discussed here.

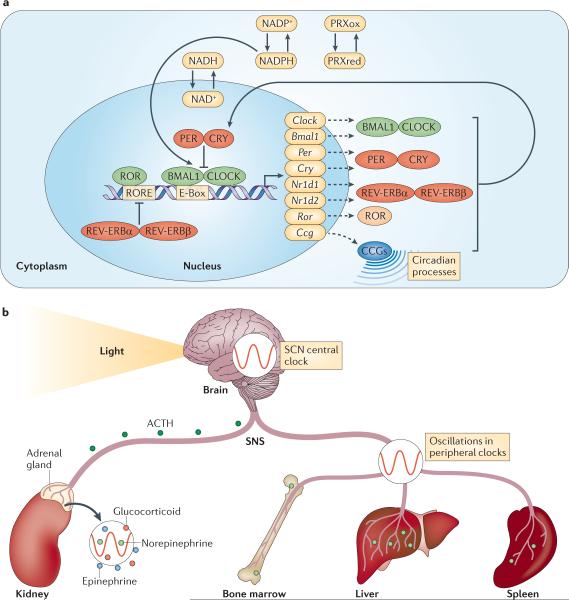

At the molecular level, the clock consists of multiple sets of transcription factors that result in autoregulatory transcription-translation feedback loops (TTFLs) (Fig. 1a). Transcription of the core clock genes BMAL1 (brain and muscle Arnt-like protein 1) and CLOCK (circadian locomotor output cycles kaput), or its related gene NPAS2 (neuronal PAS domain containing protein-2; mainly expressed in the forebrain), results in the heterodimerization of the BMAL1–CLOCK complex in the cytoplasm, triggering its nuclear translocation where it binds to canonical Enhancer Box (E-Box)-sequences of clock controlled genes (CCGs, Box 1)16. In addition, BMAL1 and CLOCK promote their own repression by inducing the expression of their negative regulators PER (period) and CRY (cryptochrome). The PER–CRY heterodimer translocates to the nucleus and interacts with BMAL1–CLOCK to inhibit transcription. The cycle starts anew when expression of PER–CRY wanes due to reduced BMAL1–CLOCK levels.

Figure 1.

a) The molecular clock.

Transcription of the core clock genes Bmal1 and Clock (or its related gene Npas2, not shown) results in their heterodimerization in the cytoplasm and ensuing nuclear translocation. These helix-loop-helix transcription factors bind to canonical E-Box sequences (CACGTG) of clock-controlled genes (CCGs), driving circadian processes and their own expression. In addition, the expression of negative (PER and CRY) as well as positive (retinoic acid-related orphan receptor (ROR)) regulators of this cycle is induced. The PER/CRY complex represses binding of BMAL1–CLOCK to target genes, whereas ROR binding to ROR responsive elements (ROREs) in the Bmal1 promoter induces expression. After a period of time, the PER/CRY complex is degraded and BMAL1–CLOCK activates another transcription cycle. A second autoregulatory feedback loop is induced by transcription of REV-ERBα and REV-ERBβ (encoded by Nr1d1 and Nr1d2). The REV-ERBα–REV-ERBβ complex represses Bmal1 transcription and competes with ROR for binding of ROREs. While this pathway stabilizes the clock it can also directly drive circadian rhythms. The molecular clock does not only depend on transcriptional/translational feedback but is also regulated by rhythms in post-translational modifications of proteins such as oxidation cycles of peroxiredoxins (PRXox(idized)/PRXred(uced)) as well as NADPH and NADH, the latter of which can modulate the binding of the BMAL1/CLOCK complex to DNA directly.

b) Entrainment and synchronization.

Circadian rhythms are entrained by external cues, of which light is a major contributor. Light is processed via the retina, leading to synchronization of rhythms in hypothalamic suprachiasmatic nuclei, which comprise the master clock of the organism. From here, humoral and neural output systems modulate clocks in peripheral tissues via the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, setting a common phase. Release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) from the pituitary gland likely cooperates with the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) to regulate rhythmic release of hormones (glucocorticoids, epinephrine and norepinephrine) from the adrenal glands. In addition the SNS directly innervates tissues, and can modulate circadian rhythms locally via cyclical release of norepinephrine from nerve varicosities.

The role of the nuclear receptors REV-ERBα (encoded by Nr1d1) and REVERBβ (encoded by Nr1d2), which were previously thought to form an accessory feedback loop that stabilizes the clock, has been recently refined as a more integral part of this pathway capable of driving circadian rhythms17. Nr1d1−/−Nr1d2−/− mice showed a complete loss of circadian rhythm, comparable to other clock-deficient strains (such as Per1−/−Per2−/− and Cry1−/−Cry2−/−)17. Although the transcriptional regulation of these clock genes has long been the paradigm for the control of circadian rhythms, recent surprising observations in red blood cells and algae have revealed that circadian oscillations can exist solely due to rhythmic modifications at the posttranslational level18, 19. These data indicate that regulation of the clock occurs at many different levels, thereby increasing the stability of the system.

Peripheral clocks

The central clock orchestrates a uniform temporal program across the whole organism by synchronizing multiple peripheral clocks that oscillate autonomously and exist in virtually all cells, thus setting a common rhythm (Fig. 1b). Clocks in peripheral tissues employ essentially the same molecular components as in the SCN and with respect to the immune system have so far been reported to exist in different hematopoietic cell lineages, including macrophages and lymphocytes8, 20, 21.

Rhythmic synchronization of the body occurs indirectly via behavioral rest– activity cycles but also in a direct manner via a complex and incompletely understood interplay between hormones and local autonomic innervation14, 22 (Fig. 1b). Key hormones implicated in this process — glucocorticoids and catecholamines (epinephrine and norepinephrine) — are released by the adrenal gland via the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis; norepinephrine is also derived from sympathetic nerves. The HPA receives input from the SCN via neurons that target the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, which induces the pituitary to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), thus regulating the activity of the adrenal gland14, 22. Glucocorticoids act through the glucocorticoid receptor, which is expressed by almost all mammalian cells (except SCN neurons) and can inhibit the synthesis of pro-inflammatory factors while promoting the expression of anti-inflammatory mediators23. Catecholamines act via α-adrenergic and α-adrenergic receptors, which can have diverse effects on the immune system, including increasing the numbers of neutrophils and natural killer (NK) cells in blood, and boosting humoral immune responses (reviewed in 23).

The variety of factors involved in the synchronization of peripheral clocks may secure stability and allow the organism to maintain the overall rhythm even following brief disruption of environmental (zeitgeber) signals. Indeed, in animals with glucocorticoid-receptor deficiencies or after adrenalectomy, the circadian rhythm is disrupted more easily than in control animals when challenged with out-of-phase zeitgebers24. A previously unrecognized but important factor in the synchronization process is the autonomic innervation of tissues, and the local release of norepinephrine from nerve varicosities22, 23. Although much progress has been made thus far, more studies are needed to dissect the influence of different synchronizing mechanisms at the cellular level in various tissues.

Rhythms in immune parameters

Circulating cellular and humoral elements

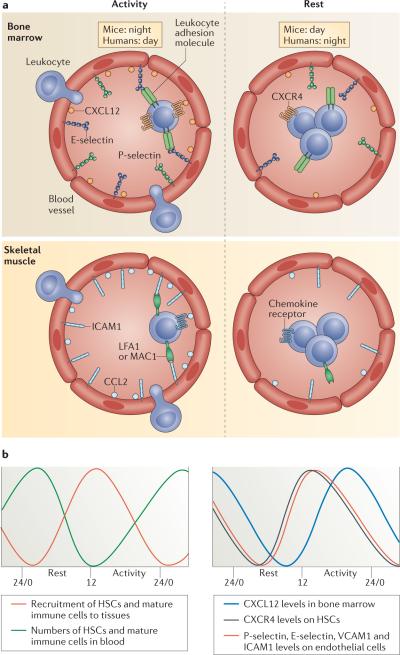

Key parameters of the immune system in the blood exhibit circadian rhythms, most strikingly the number of circulating hematopoietic cells, as well as hormones and cytokines25. These factors oscillate according to the rest–activity phase of the species, whether the species is diurnal (e.g. humans) or nocturnal (e.g. rodents) (Fig. 2a). The immune cellular and humoral components in the blood display opposite rhythms: the numbers of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) and most mature leukocytes (with the exception of effector CD8+ T cells26) peak in the circulation during the resting phase (during the night for humans and during the day for rodents) and decrease during the active period25, 27 (Table 1 and Fig. 2a-b). In addition, HSPCs and mature immune cells are released from the bone marrow into the blood at the beginning of the resting phase28. This release is dependent on local sympathetic innervation, which mediates the rhythmic downregulation of the expression of CXC-chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12; previously known as SDF1)28, a major retention factor for hematopoietic cells in the bone marrow. This coincides with reduced levels of its receptor CXCR4 on HSPCs29, as well as on CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subsets26. By contrast, the levels of glucocorticoids (cortisol in humans and corticosterone in mice), epinephrine, norepinephrine, and the pro-inflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) peak during the onset of the active phase25, 27. These observations may have implications for associations with circadian onset of diseases (discussed below).

Figure 2. Rhythms in immune cell function.

a) Rest-activity cycles in diurnal humans and nocturnal mice. In murine bone marrow and skeletal muscle, leukocyte recruitment is enhanced during the active phase due to higher expression levels of chemokines as well as adhesion molecules on both the endothelium and hematopoietic cells. In peripheral tissues, the molecules oscillating on leukocytes mediating circadian recruitment are not known but likely include CCR2, the receptor for CCL2, and the ICAM-1 binding integrins LFA-1 and Mac-1. During the resting phase, lower adhesion molecule and chemokine expression as well as enhanced mobilization from the bone marrow results in reduced leukocyte recruitment and enhanced numbers of immune cells in blood. b) Oscillation of factors known to contribute to circadian trafficking of hematopoietic cells showing in-phase expression of pro-migratory factors.

Table 1.

Rhythms in immune cell function

| Acrophase during the resting phase | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Source | Oscillating parameter | Acrophase | Trough | Refs |

| Human | Blood | Neutrophils | CT20 | CT8 | 25 |

| Naive, central memory, effector memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells | CT2 | CT14 | 26 | ||

| HSCs | CT20 | CT8 | 29 | ||

| HSC mobilization from the BM | Afternoon | Morning | |||

| Mouse | Blood | Neutrophils, monocytes, lymphocytes, eosinophils | ZT5 | ZT13 | 7 |

| HSCs | ZT5 | ZT13 | 28 | ||

| HSC mobilization from the BM | 29 | ||||

| Spleen | Macrophages, B cells | CT8 | CT16 | ||

| Rat | Spleen/lymph node | Splenocyte proliferation | CT9-13 | CT21-1 | 30 |

| Acrophase during the active phase | |||||

| Human | Blood | Effector CD8+ T cells | CT14 | CT2 | 26 |

| Cortisol, epinephrine, norepinephrine | CT8-11 | CT1-5 | 26 | ||

| Naive, central memory CD4+ and CD8+ cells | CXCR4 | CT9 | CT21 | 26 | |

| Mature CD8+ cells | CX3CR1 | CT9 | CT21 | 26 | |

| Mouse | Bone marrow Muscle/liver | Neutrophil/HSC homing Monocyte/neutrophil recruitment | ZT13 | ZT1-5 | 7 |

| Bone marrow | CXCL12 | ZT21 | ZT9 | 28 | |

| Bone marrow ECs Muscle ECs | P-selectin, E-selectin, VCAM-1 ICAM-1, Ccl2 | ZT13 | ZT5 | 7 | |

| HSCs | CXCR4 | ZT13 | ZT5 | 29 | |

| Splenic B cells/ Macrophages | TLR9 | ZT19 | ZT7 | 9 | |

| Splenic macrophages | Tnf, Ccl2 | CT16-20 | CT24 | 8 | |

| Mouse/ Rat | Neutrophils | Phagocytic activity | CT3-4 | CT10-16 | 40 |

| Rat | NK cells | Granzyme, Perforin, IFNv, TNF | ZT14-24 | ZT2-6 | 39 |

| Muscle | Neutrophil recruitment | CT17 | CT11 | 35 | |

CT: actual circadian time in hours (e.g. CT6 = 6AM); ZT: Zeitgeber time: time after the onset of light with lights on at ZT0/24 and off at ZT12; EC: endothelial cells; HSC: hematopoietic stem cell; BM: bone marrow.

Rhythms in tissue constituents

In contrast to their acrophases in blood during the resting phase, the migration of hematopoietic cells to tissues preferentially occurs during the active phase. Accordingly, in mice the homing of HSCs and neutrophils to the bone marrow, as well as monocyte recruitment to muscle tissue, peaks at night7. Circadian leukocyte migration is regulated locally by sympathetic nerves and is mediated by rhythmic expression of endothelial cell adhesion molecules and chemokines7.

Interestingly, adhesion molecule expression is differentially regulated in different tissues: the expression of bone marrow homing receptors P-selectin, E-selectin and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM1) oscillates in the bone marrow but not skeletal muscle, whereas ICAM1 expression, but not these homing receptors, oscillates in the latter7. This suggests that rhythms in the expression of these adhesion molecules drive the recruitment of hematopoietic cells to tissues. How different tissues regulate the expression of distinct molecules through the same adrenergic signals is currently unknown. Oscillations in the expression of pro-migratory molecules by hematopoietic cells have also been described, including CX3CR1 on CD8+ T cells26 and CXCR4 on T cells26 and HSPCs29 as detailed above. This argues for a contribution of both cell-autonomous and non-cell autonomous mechanisms for circadian recruitment of immune cells, enhancing the efficacy of leukocyte–endothelial cell interactions by the in-phase expression of receptor–ligand pairs.

The physiological role of circadian leukocyte trafficking is currently unclear. In the bone marrow, the circadian homing of neutrophils may serve as a feedback mechanism for bone marrow stromal cells to sense leukocyte concentrations in the blood and trigger the next round of cyclical hematopoietic cell release. In peripheral tissues, the circadian recruitment of leukocytes to tissues (which is at its peak during the active phase) may exist to replenish resident leukocyte populations, and contribute to healing muscle injuries that are prevalent during physical activity and maintain the immunosurveillance of the body. The latter might represent its most important function, since rhythmic bacterial encounters — which are likely to be maximal during the active phase — could have been a potent evolutionary driver for the circadian emigration of leukocytes.

There are conflicting data about whether the regulation of lymphocyte numbers in lymphoid tissues occurs in a cyclical fashion, with studies in rodents reporting increased proliferation of lymphocytes in lymph nodes and spleen during the day (during the rest phase)30, whereas more lymphocytes have been reported to be present in the thymus and spleen at night (during the active phase)8, 31. Therefore, circadian trafficking behavior of lymphocytes requires further study. Taken together, leukocyte trafficking across different tissues occurs in a circadian manner, orchestrated by the in-phase expression of cell adhesion molecules and chemokines.

Circadian rhythms and disease

Circadian response to acute inflammatory insults

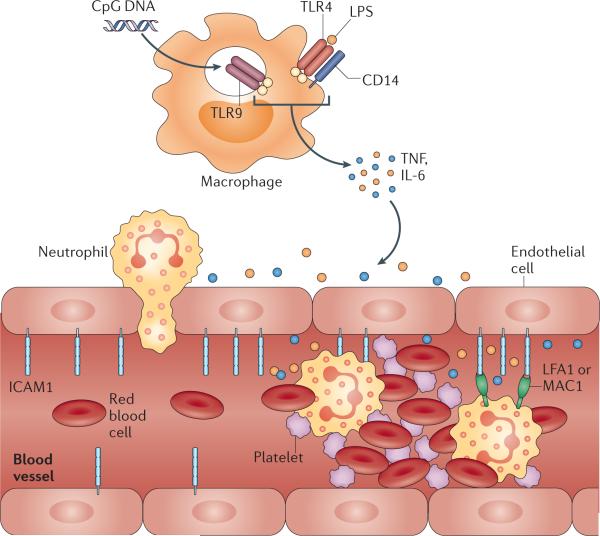

It has been known since pioneering work of the 1960s and ‘70s that the response of mice to various pathogens and their by-products, such as bacterial endotoxins and exotoxins, and pro-inflammatory cytokines, is under diurnal control7, 9, 32-37. Collectively, these studies show that mice are highly sensitive and subject to greatly reduced survival when exposed to these factors towards the beginning of the active phase (that is, early evening). This response is incompletely understood but appears to be tightly balanced to detect and fight pathogen encountered locally under physiological conditions when antigen exposure is maximal. The phenomenon may be due to a combination of factors (Fig. 3). One, increased expression of adhesion molecules and chemokines at this time point provides greater leukocyte infiltration into the tissue (see above)7. This results in higher numbers of activated leukocytes in tissues and an increased potential to cause tissue damage.

Figure 3. Contributing factors in circadian disease onset.

Cyclical exposure to pathogens or other inflammatory insults is matched by oscillations in the expression of pattern recognition receptors (PPRs) on tissue macrophages such as toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) and TLR4-associated factors. These recognize microbial CpG DNA and lipopolysaccharides (LPS), respectively, which triggers signaling events that lead to cyclical release of the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF and IL-6. These cytokines can induce inflammation both locally and systemically, resulting in the recruitment of leukocytes from the circulation to combat the infection. Leukocyte trafficking is under circadian control, with circadian release from the bone marrow and cyclical recruitment to tissues, the latter being due to enhanced expression of pro-migratory factors such as intercellular cell adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1) on endothelial cells. Rhythmic leukocyte/endothelial cell interactions can contribute to obstructing blood flow in small caliber vessels by exacerbating leukocyte activation, prompting their interactions with other free-flowing blood components such as red blood cells (RBCs), and potentially causing thrombus formation and vascular infarction as observed in sickle cell disease.

Two, mice exhibit an enhanced sensitivity to detect pathogens during the active phase due to increased expression of components of the innate immune system, such as the pattern recognition receptor (PPR) Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9)9, as well as Cd14, Nfkbia (IκBα) and the transcription factors Rela (p65 NF-κB), Fos and Jun — downstream signaling components of TLR48. Mice stimulated with a TLR9 agonist showed circadian oscillations in the expression of Tnf and Ccl2 peaking at night. Arrhythmic mice carrying a nonfunctional Per2 gene (Per2Brdm1) expressed significantly lower levels of Ccl2 than wild-type mice9. In a separate study, stimulation with the TLR4 ligand lipopolysaccharide (LPS) at the beginning of the active phase yielded significantly elevated serum levels of IL-6, IL-12, CCL5, CXCL1 and CCL2 compared with the beginning of the resting phase38. This was shown to be dependent on the expression of clock genes: Bmal1−/− macrophages and Nr1d1−/− mice (which are deficient for REV-ERBα) did not exhibit these oscillations38. The high cytokine levels released at this time point likely exacerbate the ongoing local inflammation. The mouse Tlr9 promoter region has two non-canonical E-boxes, to which the BMAL1–CLOCK heterodimer can bind9, providing an immediate functional link between innate immunity and circadian rhythms8, 9.

Three, leukocytes display higher phagocytic ability and cytotoxicity during the active phase39-41 but whether this is directly regulated by clock genes is currently unknown. Interestingly, such circadian responses to acute inflammatory insults are not restricted to mammals but also seen in flies and plants, indicating the adaptation of diverse organisms to maximize a reaction (and to overreact when stimulated with non-physiological doses) at times when encounters with pathogens are most likely to occur42-48. In mice, it is conceivable that this would peak at the beginning of the phase of physical activity when the mouse starts feeding and exploring the environment. In contrast, for the plant Arabidopsis, this depends on the activity phase of its pathogen, downy mildew, which disperses its infectious spores at dawn48.

Circadian timing in disease manifestations

Several chronic diseases are known to exhibit circadian exacerbations in their symptoms or presentations (Table 2)49-54. For example, patients with rheumatoid arthritis experience joint stiffness in the early morning, which has been correlated with enhanced serum levels of TNF and IL-650. Susceptibility to cardiovascular complications such as stroke and myocardial infarction also peaks at this time51, 52, 55. This has been linked to a surge in the activity of the sympathetic nervous system in the early morning hours, leading to increased blood pressure as well as enhanced viscosity and coagulability of the blood and thus a predisposition to thrombosis56. In addition, recent evidence suggests that ischemic cells in the brain can release peroxiredoxins — cytosolic antioxidant proteins that are vital for redox balance and are conserved markers of circadian rhythms2 — that can bind to TLR2 and TLR4 on brain infiltrating macrophages, inducing the release of IL-23 and the recruitment of pro-inflammatory IL-17+ T cells which may aggravate brain damage57.

Table 2.

Influence of circadian timing on disease manifestations

| Species | Disease/model | Oscillating parameter | Acrophase | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | Rheumatoid arthritis | Stiffness, Pain, Serum TNF, IL-6 | CT5-8 | 50 |

| Allergic rhinitis | Sneezing, nasal congestion | CT6 | 54 | |

| Bronchial asthma | Broncho- constriction | CT6 | 54 | |

| Sputum eosino- phils, Serum IL-5 | CT7 | 53 | ||

| Myocardial infarction | Pain | CT9 | 52 | |

| Ischemic stroke | Hypertension | CT6-12 | 51 | |

| Sickle cell vaso-occlusive crisis | Hospital admission | CT18 | 49 | |

| Mouse | LPS-induced inflammation | Lethality | CT16 | 34 |

| LPS-induced inflammation | Lethality, Leukocyte recruitment, ICAM-1 | ZT13 | 7 | |

| Pneumococcal infection | Lethality | CT16 | 33, 37 | |

| CLP-induced sepsis | Lethality, TLR9 on splenic macrophages | ZT19 | 9 | |

| Coxsackie B3 virus infection | Gross myocardial lesions | CT16 | 32 | |

| TNF-induced inflammation | Lethality | ZT10 | 36 | |

| Sickle cell vaso-occlusion | Lethality, Leukocyte adhesion, RBC- WBC interactions | ZT13 | 7 |

CLP: cecal ligation and puncture; RBC: red blood cell; WBC: white blood cell

In addition to the increased occurrence of myocardial infarction in the morning, infarct sizes were also found to be larger, suggesting that rhythmic leukocyte infiltration could play a contributing role58. It is intriguing that the number of leukocytes in blood correlates with the incidence of cardio-vascular events59. Leukocyte adhesion plays a critical role in sickle cell vaso-occlusion as mortality is prevented in mice deficient in both P- and E-selectin60, 61. Circadian time affects vaso-occlusive events in humans49 and mice7, further supporting their contribution to circadian onset of vascular diseases. It is likely that multiple circadian-regulated cellular and humoral factors modulate disease onset and progression.

Chronopharmacology

Clock genes are linked to the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, TNF and CXCL138, 62, and have been implicated in a variety of diseases including cancer development63-65. Cry1−/−Cry2−/− macrophages are arrhythmic and show enhanced levels in all three cytokines62. This does not seem to be due to direct transcriptional regulation but rather has been linked to the loss of CRY binding to adenylyl cyclase, resulting in enhanced cAMP levels and constitutive protein kinase A and NF-κB activity62. It is currently unclear whether an association with disease is due to a general alteration of circadian rhythms or an impaired activity of the clock genes. However, at least in Nr1d1−/− animals, which show elevated and non-oscillating IL-6 levels after LPS stimulation compared with wild-type mice but otherwise robust circadian oscillations, a direct transcriptional activity of REV-ERBα in the regulation of this cytokine appears to be important38.

In humans, the impact of altered rhythms on health has been relatively well characterized and is generally accepted. Both frequent jetlag and shift work are significantly associated with the development of cancer66-68. In addition, evidence exists that the preservation of circadian rhythms provides better recovery in a cecal ligation and puncture (CLP)-induced rat model of sepsis69. Animals that were transferred to constant conditions after CLP exhibited significantly reduced survival compared to rats left under a 12 hour light–dark cycle69 indicating that strictly enforced daily lighting patterns in the intensive care unit could improve the recovery of septic patients. Our current understanding of circadian rhythms in the immune system will give us a better appreciation of how to improve on current therapies by taking into account chronopharmacological considerations.

Ongoing studies aim to time the administration of drugs according to their peak efficacy while exerting minimal side effects70-72. For this, drug pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics need to be taken into consideration73. In a vaccination model, Fikrig and colleagues showed that lymphocyte cultures harvested from mice that were immunized with a TLR9 ligand as adjuvant at the time of enhanced TLR9 responsiveness exhibited an increased antigen-induced proliferative response and IFNγ production four weeks later9. Synthetic oligodeoxynucleotides, which trigger TLR9 may prove to have long-lasting effects by enhancing the antibody titer in vaccination strategies when administered at the time of highest TLR9 expression (presumably occurring in the morning in humans).

Cyclical homing and mobilization efficiencies of HSCs could be clinically exploited to enhance the isolation of mobilized HSCs at the acrophase in blood (which occurs at night in humans)29. These cells should then be transplanted back at the peak of HSC homing activity to the bone marrow, which is predicted to be during the day in humans7. The use of β3 adrenergic receptor agonists could additionally improve engraftment as these induce expression of homing receptors (P-selectin, E-selectin and VCAM1) by bone marrow endothelial cells, which is associated with enhanced recruitment of HSCs7. A more general approach to reset circadian rhythms comes in the form of synthetic REV-ERB agonists, which in an animal model of obesity led to increased energy expenditure and may thus be important in treating metabolic diseases74. With respect to the immune system, the REV-ERB ligand GSK4112 has recently been shown to suppress the expression of Il6, Cxcl11, Ccl2 and Cxcl6 in primary human macrophages in response to LPS38. These recent developments suggest that immunochronotherapy should be further studied as it could represent a useful ally to existing therapeutic regiments. In addition, circadian time should already be taken into account when harvesting human tissue samples such as blood and biopsies at different times of the day as circadian rhythms may introduce considerable variability among samples. The same holds true in experimental settings using pre-clinical animal models since the immune response can vary significantly over the course of a day.

Conclusions

Numerous studies have provided strong links between circadian rhythms and the immune system. Much work remains to be done, however, with regards to implementing these observations in the clinic and to integrating the breadth of circadian influences into a multifaceted immune response. One could envision that simple therapeutic changes taking into account the circadian time may impact clinical care as much as the development of a new drug, at a fraction of the cost. A greater mechanistic understanding of rhythms in the immune response will be critical to identify new opportunities in the development of time-based interventions that harness endogenous predispositions.

Preface.

Circadian rhythms, long known to play crucial roles in physiology, are emerging as critical regulators of specific immune functions. Circadian oscillations of immune mediators coincide with the activity of the immune system, possibly allowing the host to anticipate and handle microbial threats more efficiently. These oscillations may also help to promote tissue recovery, and the clearance of potentially harmful cellular elements from the circulation. This review summarizes the current knowledge of circadian rhythms in the immune system and provides an outlook on potential future implications.

Box 1 Clock-controlled genes.

Since the molecular clock consists of a set of transcription–translation feedback loops, a significant fraction of the output is directed at the control of the clock mechanism itself. In addition, many other genes outside the clock machinery are under direct circadian regulation by binding clock transcription factors, driving biological processes in a cyclical manner. These clock-controlled genes exhibit E-box motifs allowing the binding of BMAL1–CLOCK, RORE motifs as binding sites for ROR and REV-ERB family members, and D-elements as docking sites for PAR BZIP factors. In the SCN, liver and heart up to 10% of expressed genes exhibit circadian regulation3, 4. The number of circadian-regulated functions is probably higher as this does not account for transcription independent regulation of mRNA and proteins. This does not mean that all circadian transcripts are direct, transcriptional targets of the clock. Rather, the process appears hierarchical where a clock-controlled gene (e.g. a hormone, transcription factor, transmembrane receptor or an enzyme) may serve as an intermediary and drive expression of other genes or regulate the functions of other proteins. An example for the immune system is Tlr9, which is under direct circadian control of BMAL1–CLOCK transcription factors and renders the whole cell more sensitive to detection of bacterial DNA at specific times9, thus inducing the circadian expression of genes that under steady-state conditions may neither be expressed nor cycle. It is also important to note that only a small percentage of all oscillating genes in one tissue oscillates in another (although they are expressed), suggesting tissue-specific regulation of the oscillation mechanisms and indicating that these are probably controlled in an indirect manner by clock genes.

Online Summary.

Circadian rhythms are endogenous oscillations in organisms of ~24 hour in length that exist in virtually all cells.

The most striking immune parameter, the number of circulating leukocytes, oscillates in blood in a manner according to the phase of physical activity of the organism. Generally, the peak occurs during the resting phase.

In contrast to circulating leukocytes, leukocyte recruitment to tissues occurs preferentially during the active phase of the organism. It is mediated by the in-phase expression of cell adhesion molecules and chemokines.

The organism's response to acute inflammatory insults exhibits circadian oscillations. This is most likely due to a combination of circadian regulated leukocyte trafficking, expression of pathogen-sensitive receptors and phagocytic activity of leukocytes.

Chronic diseases exhibit circadian exacerbations in their symptoms or presentations, which has been linked to an exaggeration of the circadian expression of pro-inflammatory mediators.

Circadian rhythms should be taken into account when harvesting human tissue samples and in experimental settings using pre-clinical animal models. In addition, chronopharmacology holds great promise to impact clinical care in the future.

Acknowledgments

Our work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 HL097700, DK056638, HL097819, HL116340, HL069438) to P.S.F., the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) to C.S. and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science to Y.K.

Glossary terms

- Sympathetic nerves

Belong to the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), which along with the parasympathetic nervous system, makes up the autonomic nervous system. The SNS is under involuntary control and acts to mobilize the body's fight-or-flight response, among other functions.

- Diurnal

A pattern that occurs during the day, in contrast to nocturnal.

- Rest–activity cycle

Species-specific rhythm determined by diurnal (humans) or nocturnal (rodents) periods of activity followed by times of rest.

- Suprachiasmatic nuclei

A pair of nuclei, each consisting of approximately 10,000 highly interconnected neurons that are located in a small region of the hypothalamus, above the optic chiasm from where they receive environmental light input through the retinohypothalamic tract.

- Retinohypothalamic tract

Connects photosensitive retinal ganglion cells directly to the suprachiasmatic nuclei of the hypothalamus.

- Entrainment

The alignment of an organism's endogenous circadian rhythm with an external rhythm.

- Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis

The HPA axis consists of a complex set of input and feedback mechanisms between the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland and the adrenal gland. It is a major part of the neuroendocrine system.

- Acrophase

Time at which the peak of a rhythm occurs.

- Zeitgeber

An environmental cue such as light, food or temperature that synchronizes an organism's endogenous rhythm to the earth's 24-hour light/dark cycle.

Biography

Christoph Scheiermann received his PhD in vascular biology from Imperial College London before joining the lab of Paul S. Frenette. He is the recipient of an Emmy-Noether award from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) to head his own laboratory focusing on the circadian regulation of immune functions.

Yuya Kunisaki received M.D. and Ph.D. with Dr. Yoshinori Fukui at the Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan and is a research fellow at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, USA, where he focuses on the trafficking of hematopoietic stem cells and immune cells by in vivo and ex vivo imaging.

Paul S. Frenette obtained his medical degree from Laval University, Quebec, Canada, and did a medical residency at McGill University, Montreal, Canada followed by a fellowship in hematology-oncology at the New England Medical Center, Boston MA, USA. He then studied in the laboratories of Denisa Wagner at Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA, and Richard Hynes at MIT, Boston, Massachusetts, USA before taking a faculty position at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York, USA. He became the founding director of the Ruth L. and David S. Gottesman Institute for Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine at Einstein in 2010. His research interests have focused on the neural regulation of stem cell microenvironments, hematopoietic cell migration and the vascular biology of sickle cell disease.

References

- 1.Halberg F, Halberg E, Barnum CP, Bittner JJ. Physiological 24-hour Periodicity in Human Beings and Mice, the Lighting Regimen and Daily Routine. In: Withrow RB, editor. Photoperiodism and Related Phenomena in Plants and Animals. 1959. pp. 803–78. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edgar RS, et al. Peroxiredoxins are conserved markers of circadian rhythms. Nature. 2012;485:459–64. doi: 10.1038/nature11088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Panda S, et al. Coordinated transcription of key pathways in the mouse by the circadian clock. Cell. 2002;109:307–20. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00722-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Storch KF, et al. Extensive and divergent circadian gene expression in liver and heart. Nature. 2002;417:78–83. doi: 10.1038/nature744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arjona A, Silver AC, Walker WE, Fikrig E. Immunity's fourth dimension: approaching the circadian-immune connection. Trends Immunol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.08.007. [Nice overview of the recent developments in the circadian immunology field.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lange T, Dimitrov S, Born J. Effects of sleep and circadian rhythm on the human immune system. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1193:48–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scheiermann C, et al. Adrenergic nerves govern circadian leukocyte recruitment to tissues. Immunity. 2012;37:290–301. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.05.021. [The first study to show a circadian rhythm in leukocyte recruitment to tissues and the implication in homeostasis and inflammation.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keller M, et al. A circadian clock in macrophages controls inflammatory immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:21407–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906361106. [This study describes a macrophage-intrinsic clock that drives the circadian expression of the signaling pathways involved in the response to endotoxins.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silver AC, Arjona A, Walker WE, Fikrig E. The circadian clock controls toll-like receptor 9-mediated innate and adaptive immunity. Immunity. 2012;36:251–61. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.017. [This paper shows that a circadian rhythm in TLR9 expression has long term implications for immunization and adaptive immunity.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aschoff J. Exogenous and endogenous components in circadian rhythms. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1960;25:11–28. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1960.025.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green CB, Takahashi JS, Bass J. The meter of metabolism. Cell. 2008;134:728–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Golombek DA, Rosenstein RE. Physiology of circadian entrainment. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:1063–102. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00009.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ralph MR, Foster RG, Davis FC, Menaker M. Transplanted suprachiasmatic nucleus determines circadian period. Science. 1990;247:975–8. doi: 10.1126/science.2305266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dibner C, Schibler U, Albrecht U. The mammalian circadian timing system: organization and coordination of central and peripheral clocks. Annu Rev Physiol. 2010;72:517–49. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takahashi JS, Hong HK, Ko CH, McDearmon EL. The genetics of mammalian circadian order and disorder: implications for physiology and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:764–75. doi: 10.1038/nrg2430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bunger MK, et al. Mop3 is an essential component of the master circadian pacemaker in mammals. Cell. 2000;103:1009–17. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00205-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho H, et al. Regulation of circadian behaviour and metabolism by REV-ERB-alpha and REV-ERB-beta. Nature. 2012;485:123–7. doi: 10.1038/nature11048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Neill JS, Reddy AB. Circadian clocks in human red blood cells. Nature. 2011;469:498–503. doi: 10.1038/nature09702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Neill JS, et al. Circadian rhythms persist without transcription in a eukaryote. Nature. 2011;469:554–8. doi: 10.1038/nature09654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boivin DB, et al. Circadian clock genes oscillate in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Blood. 2003;102:4143–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bollinger T, et al. Circadian clocks in mouse and human CD4+ T cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e29801. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dickmeis T. Glucocorticoids and the circadian clock. J Endocrinol. 2009;200:3–22. doi: 10.1677/JOE-08-0415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elenkov IJ, Wilder RL, Chrousos GP, Vizi ES. The sympathetic nerve--an integrative interface between two supersystems: the brain and the immune system. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:595–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Le Minh N, Damiola F, Tronche F, Schutz G, Schibler U. Glucocorticoid hormones inhibit food-induced phase-shifting of peripheral circadian oscillators. EMBO J. 2001;20:7128–36. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.24.7128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haus E, Smolensky MH. Biologic rhythms in the immune system. Chronobiol Int. 1999;16:581–622. doi: 10.3109/07420529908998730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dimitrov S, et al. Cortisol and epinephrine control opposing circadian rhythms in T cell subsets. Blood. 2009;113:5134–43. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-11-190769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haus E, Lakatua DJ, Swoyer J, Sackett-Lundeen L. Chronobiology in hematology and immunology. Am J Anat. 1983;168:467–517. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001680406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mendez-Ferrer S, Lucas D, Battista M, Frenette PS. Haematopoietic stem cell release is regulated by circadian oscillations. Nature. 2008;452:442–7. doi: 10.1038/nature06685. [The first study to show that hematopoietic stem cells are released into the blood from the bone marrow in a circadian manner dependent on CXCL12.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lucas D, Battista M, Shi PA, Isola L, Frenette PS. Mobilized hematopoietic stem cell yield depends on species-specific circadian timing. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:364–6. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.09.004. [This paper describes circadian oscillations in hematopoietic stem cell yield harvested from human blood.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cardinali DP, Brusco LI, Selgas L, Esquifino AI. Diurnal rhythms in ornithine decarboxylase activity and norepinephrine and acetylcholine synthesis in submaxillary lymph nodes and spleen of young and aged rats during Freund's adjuvant-induced arthritis. Brain Res. 1998;789:283–92. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Litvinenko GI, et al. Circadian dynamics of cell composition of the thymus and lymph nodes in mice normally, under conditions of permanent illumination, and after melatonin injection. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2005;140:213–6. doi: 10.1007/s10517-005-0448-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feigin RD, Middelkamp JN, Reed C. Circadian rhythmicity in susceptibility of mice to sublethal Coxsackie B3 infection. Nat New Biol. 1972;240:57–8. doi: 10.1038/newbio240057a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feigin RD, San Joaquin VH, Haymond MW, Wyatt RG. Daily periodicity of susceptibility of mice to pneumococcal infection. Nature. 1969;224:379–80. doi: 10.1038/224379a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Halberg F, Johnson EA, Brown BW, Bittner JJ. Susceptibility rhythm to E. coli endotoxin and bioassay. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1960;103:142–4. doi: 10.3181/00379727-103-25439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.House SD, Ruch S, Koscienski WF, 3rd, Rocholl CW, Moldow RL. Effects of the circadian rhythm of corticosteroids on leukocyte-endothelium interactions in the AM and PM. Life Sci. 1997;60:2023–34. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)00167-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hrushesky WJ, Langevin T, Kim YJ, Wood PA. Circadian dynamics of tumor necrosis factor alpha (cachectin) lethality. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1059–65. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.3.1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shackelford PG, Feigin RD. Periodicity of susceptibility to pneumococcal infection: influence of light and adrenocortical secretions. Science. 1973;182:285–7. doi: 10.1126/science.182.4109.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gibbs JE, et al. The nuclear receptor REV-ERBalpha mediates circadian regulation of innate immunity through selective regulation of inflammatory cytokines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:582–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106750109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arjona A, Sarkar DK. Circadian oscillations of clock genes, cytolytic factors, and cytokines in rat NK cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:7618–24. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.7618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hriscu ML. Modulatory factors of circadian phagocytic activity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1057:403–30. doi: 10.1196/annals.1356.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Logan RW, Arjona A, Sarkar DK. Role of sympathetic nervous system in the entrainment of circadian natural-killer cell function. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25:101–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lazzaro BP, Sceurman BK, Clark AG. Genetic basis of natural variation in D. melanogaster antibacterial immunity. Science. 2004;303:1873–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1092447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee JE, Edery I. Circadian regulation in the ability of Drosophila to combat pathogenic infections. Curr Biol. 2008;18:195–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.12.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McDonald MJ, Rosbash M. Microarray analysis and organization of circadian gene expression in Drosophila. Cell. 2001;107:567–78. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00545-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roden LC, Ingle RA. Lights, rhythms, infection: the role of light and the circadian clock in determining the outcome of plant-pathogen interactions. Plant Cell. 2009;21:2546–52. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.069922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shirasu-Hiza MM, Dionne MS, Pham LN, Ayres JS, Schneider DS. Interactions between circadian rhythm and immunity in Drosophila melanogaster. Curr Biol. 2007;17:R353–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stone EF, et al. The circadian clock protein timeless regulates phagocytosis of bacteria in Drosophila. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002445. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang W, et al. Timing of plant immune responses by a central circadian regulator. Nature. 2011;470:110–4. doi: 10.1038/nature09766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Auvil-Novak SE, Novak RD, el Sanadi N. Twenty-four-hour pattern in emergency department presentation for sickle cell vaso-occlusive pain crisis. Chronobiol Int. 1996;13:449–56. doi: 10.3109/07420529609020915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cutolo M. Chronobiology and the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2012;24:312–8. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3283521c78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gupta A, Shetty H. Circadian variation in stroke - a prospective hospital-based study. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59:1272–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-5031.2005.00678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Muller JE, et al. Circadian variation in the frequency of onset of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:1315–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198511213132103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Panzer SE, Dodge AM, Kelly EA, Jarjour NN. Circadian variation of sputum inflammatory cells in mild asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:308–12. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smolensky MH, Lemmer B, Reinberg AE. Chronobiology and chronotherapy of allergic rhinitis and bronchial asthma. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2007;59:852–82. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jeyaraj D, et al. Circadian rhythms govern cardiac repolarization and arrhythmogenesis. Nature. 2012;483:96–9. doi: 10.1038/nature10852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Marfella R, et al. Morning blood pressure surge as a destabilizing factor of atherosclerotic plaque: role of ubiquitin-proteasome activity. Hypertension. 2007;49:784–91. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000259739.64834.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shichita T, et al. Peroxiredoxin family proteins are key initiators of post-ischemic inflammation in the brain. Nat Med. 2012;18:911–7. doi: 10.1038/nm.2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Suarez-Barrientos A, et al. Circadian variations of infarct size in acute myocardial infarction. Heart. 2011;97:970–6. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.212621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Coller BS. Leukocytosis and ischemic vascular disease morbidity and mortality: is it time to intervene? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:658–70. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000156877.94472.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Frenette PS, Atweh GF. Sickle cell disease: old discoveries, new concepts, and future promise. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:850–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI30920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Turhan A, Weiss LA, Mohandas N, Coller BS, Frenette PS. Primary role for adherent leukocytes in sickle cell vascular occlusion: a new paradigm. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:3047–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052522799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Narasimamurthy R, et al. Circadian clock protein cryptochrome regulates the expression of proinflammatory cytokines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:12662–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209965109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fu L, Pelicano H, Liu J, Huang P, Lee C. The circadian gene Period2 plays an important role in tumor suppression and DNA damage response in vivo. Cell. 2002;111:41–50. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00961-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Janich P, et al. The circadian molecular clock creates epidermal stem cell heterogeneity. Nature. 2011;480:209–14. doi: 10.1038/nature10649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Taniguchi H, et al. Epigenetic inactivation of the circadian clock gene BMAL1 in hematologic malignancies. Cancer Res. 2009;69:8447–54. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Filipski E, et al. Effects of chronic jet lag on tumor progression in mice. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7879–85. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Harrington M. Location, location, location: important for jet-lagged circadian loops. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2265–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI43632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Knutsson A, et al. Breast cancer among shift workers: results of the WOLF longitudinal cohort study. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2012 doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Carlson DE, Chiu WC. The absence of circadian cues during recovery from sepsis modifies pituitary-adrenocortical function and impairs survival. Shock. 2008;29:127–32. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e318142c5a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Beauchamp D, Labrecque G. Chronobiology and chronotoxicology of antibiotics and aminoglycosides. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2007;59:896–903. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gorbacheva VY, et al. Circadian sensitivity to the chemotherapeutic agent cyclophosphamide depends on the functional status of the CLOCK/BMAL1 transactivation complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:3407–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409897102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Levi F, Schibler U. Circadian rhythms: mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;47:593–628. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zmrzljak UP, Rozman D. Circadian regulation of the hepatic endobiotic and xenobitoic detoxification pathways: the time matters. Chem Res Toxicol. 2012;25:811–24. doi: 10.1021/tx200538r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Solt LA, et al. Regulation of circadian behaviour and metabolism by synthetic REV-ERB agonists. Nature. 2012;485:62–8. doi: 10.1038/nature11030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]