Abstract

Bullying is a serious problem for schools, parents and public policy makers alike. While bullying creates risks of health and social problems in childhood, it is unclear if this risk extends into adulthood. A large cohort of children was assessed for bullying involvement in childhood and then followed up in young adulthood to assess health, risky/illegal behavior, wealth and social relationships. Victims of childhood bullying including those that bullied others (bully-victim) were at increased risk of poor health, wealth and social relationship outcomes in adulthood even after controlling for family hardship and childhood psychiatric disorders. In contrast, pure bullies were not at increased risk of poor adult outcome once other family and childhood risk factors were taken into account. Being bullied is not a harmless rite of passage but throws a long shadow over affected people’s lives. Interventions in childhood are likely to reduce long term health and social costs.

Keywords: Bullying, health, social outcomes, crime, psychiatric problems, wealth

Introduction

Psychologists, economists and policy makers are interested in how early inputs in the life cycle affect later productivity (Heckman 2006). Children’s psychological problems (Goodman, Joyce et al. 2011) or exposure to abuse (Currie and Spatz Widom 2010) impact functioning decades later in adulthood. There is little information, however, about the long-term effects of problematic peer relationships, although school children spend more time at school or out of school with peers than with their parents.

Bullying is systematic abuse of power and refers to repeated aggression against another person that is intentional and involves an imbalance of power (Olweus 1994). The repeated aggression can be either direct (e.g. name calling, beating) or relational with the intent to damage relationships (e.g. spreading rumors) (Wolke, Woods et al. 2000). Children can be perpetrators of bullying or victims and some children both bully and get victimized (bully-victims). Being bullied or bullying others is a relatively common experience in childhood and adolescence (Nansel, Overpeck et al. 2001).

Children who are withdrawn, physically weak, prone to show a reaction (e.g. run away, get upset), with poor social understanding (Woods, Wolke et al. 2009) or with no or few friends who can stand up for them (Wolke, Woods et al. 2009) (Arseneault, Bowes et al. 2010) are more likely to become victims at school. Victims of bullying are at increased risk of adverse outcomes in childhood, including physical health problems, emotional and psychological problems (Reijntjes, Kamphuis et al. 2010) and reduced school achievement (Arseneault, Bowes et al. 2010; Nakamoto and Schwartz 2010). The poorer educational attainment of victims in childhood may have adverse effects on income across adulthood (Brown and Taylor 2008).

In contrast, pure bullies are often strong, healthy children (Wolke, Woods et al. 2001), and some have suggested they are competent in emotion recognition (Woods, Wolke et al. 2009) and social understanding and effective in manipulating others (Sutton, Smith et al. 1999). They have high social impact in school while being controversial (liked by some but disliked by their victims), come from disturbed families and are deviant in their behavior but not emotionally troubled (Juvonen, Graham et al. 2003). Bullies have been reported to be at increased risk for later offending (Ttofi, Farrington et al. 2011), in particular boys (Sourander, Brunstein Klomek et al. 2011).

It is “bully-victims”, those who are victims of bullying but also bully others, that seem to be the most troubled: impulsive, easily provoked, with low self-esteem, poor in understanding social cues, and unpopular with peers (Arseneault, Bowes et al. 2010). Bully-victims are also more likely to come from dysfunctional families or have pre-existing conduct, behavior or emotional problems and it has been suggested that these factors, rather than bullying per se, may explain adult outcomes (Sourander, Ronning et al. 2009).

Finally, there is some evidence for a dose-response relationship between duration of being bullied and adverse outcome in childhood. Those who are chronically bullied by peers (i.e. over years) compared to those bullied at one time point have been reported to have a higher risk for adverse outcomes such as psychiatric problems in childhood (Schreier, Wolke et al. 2009) (Winsper, Lereya et al. 2012)

This is the first study to investigate how involvement in childhood bullying and chronicity of being bullied affects a range of adult outcomes including health, risky/illegal behavior, wealth and social relationships. It tests the unique contributions of exposure to bullying in different roles, above and beyond the effects of adverse family relationships and pre- or co-existing psychiatric problems in childhood.

Methods

Sample

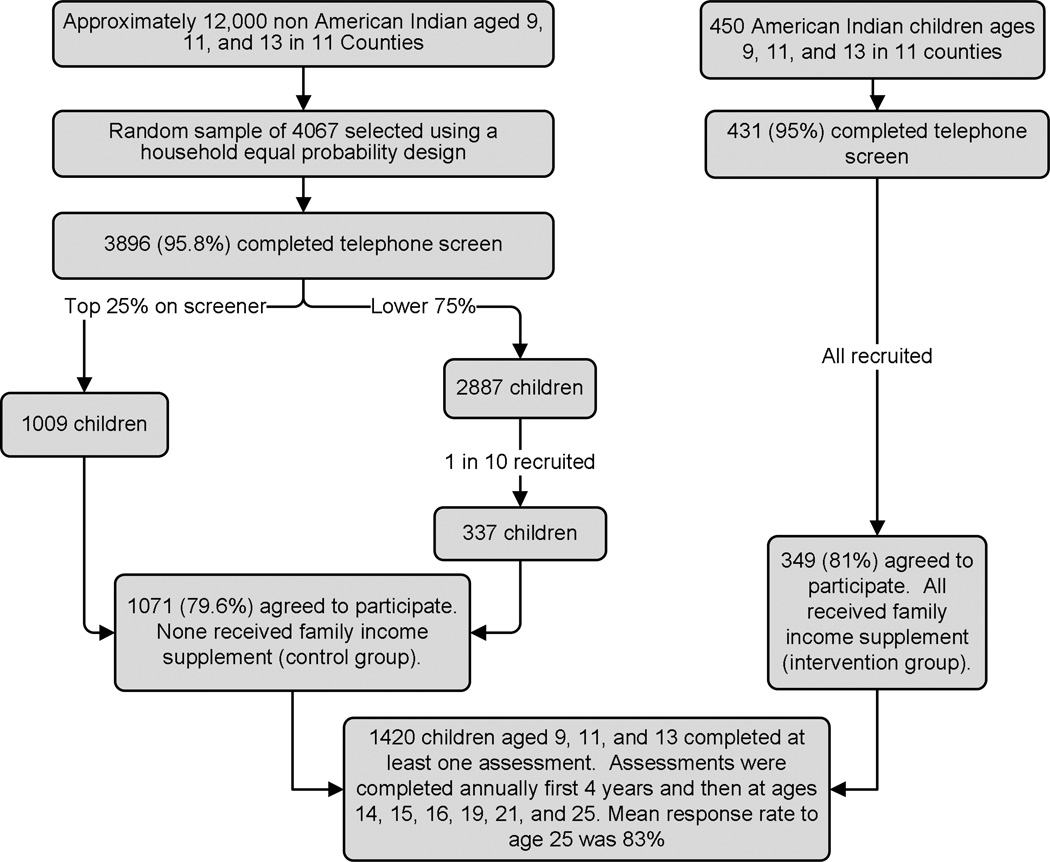

The Great Smoky Mountain Study is a population-based study of three cohorts of children, age 9, 11, and 13 at intake, recruited from 11 counties in Western North Carolina in 1993 using a multi-stage household equal probability, accelerated cohort design (see figure 1) (for full details see (Costello, Angold et al. 1996). Of all subjects recruited, 80% (N=1420) agreed to participate. The weighted sample was 49.0% female.

Figure 1.

Ascertainment strategy for the Great Smoky Mountain Study

Annual assessments were completed with the child and the primary caregiver until age 16 and then with the participant again at ages 19, 21, and 24–26 years (mean=25.0; SD=0.79). An average of 83% of possible interviews was completed overall (range: 75% to 94%). Before interviews, participants signed informed consent forms approved by the Duke University Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Of the 1420 subjects assessed in childhood, 1273 or 89.7% were followed up in young adulthood. Follow-up rates were similar across bully/victim groups (bullies: 100 of 112 or 89.3%; victims: 305 of 335 or 91.0%; bully-victims: 79 of 86 or 91.9%; neither: 789 of 887 or 89.0%) with no differences between the follow-up rate between the neither group and any of the three bully/victim groups (neither vs. bullies, p = 0.39; neither vs. victims, p = 0.95; neither vs. bullies, p = 0.93).

Measures of Childhood Bullying and Victimization

At each assessment between ages 9 and 16, the child and their parent reported on whether the child had been bullied/teased or bullied others in the 3 months immediately prior to the interview as part of the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA)(Angold and Costello 1995; Angold and Costello 2000) (full definitions provided in table 1). Being bullied or bullying others was counted if reported by either the parent or the child at any childhood or adolescent assessment. If the informant reported that the subject had been bullied or bullied others, then the informant was asked separately how often the bullying occurred in the prior 3 months in the following three settings: home, school, and the community. The focus in the current paper is on peer bullying in the school context only. Parent and child agreement on peer bullying (kappa=0.24) was similar to that of other bullying measures (Schreier, Wolke et al. 2009). Although this may seem low, a large meta-analysis of parent and self-report of behavioral and emotional functioning report similar concordance levels (Achenbach, McConaughy et al. 1987). All subjects were categorized as victims only (i.e. never indicated at any assessment that they had bullied others; N=335; 23.6%), bullies only (i.e. never indicated that they had been a victim of bullying; N=112; 7.9%), both (bully-victims: had indicated that they bullied others and had become victims at any of the assessments; N=86; 6.1%) or neither (N=887; 62.5%). Compared to the neither group, both bully-victims and bullies were more likely to be male, but victim status did not differ by sex (bully-victims: 72.4% male vs. 47.8%, p=0.009; bullies: 69.1% male vs. 47.8%, p=0.02 and victims: 52.9% male vs. 47.8%, p=0.34). For both victims and bully-victims, it was relatively common report having been bullied at more than one time point: 159 (37.8%) children/adolescents (35.8% (N=120) of those in the victim group; 45.4% (N=39) of those in the bully-victim group, not significantly different, p=.24) reported being bullied at more than one assessment point (chronic victims). The groups did not differ in terms of the percent of individuals reporting being bullied at 3 or more assessments either.

Table 1.

Definitions and interview probes for bullying and being bullied in childhood

| Variable | How assessed? | How often? | Definition | Interview Questions* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Being bullied/teased | Structured interview with the child and their parent | 4 to 6 times in the last 3 months at one or more assessment between ages 9 and 16 | Child is a particular object of repeated mockery, physical attacks or threats by peers or siblings. |

Do you get teased or bullied at all by your siblings or friends/peers? Is that more than other children? Are other boys and girls mean to you? |

| Bullying | Structured interview with the child and their parent | 4 to 6 times in the last 3 months at one or more assessment between ages 9 and 16 | Child repeatedly engages in deliberate actions aimed at causing distress to another or attempts to force another to do something against his/her will by using threats, violence, or intimidation. |

Do you ever do things to upset other people on purpose or try to hurt them on purpose? Do you ever try to get other people into trouble on purpose? Have you ever forced someone to do something s/he didn’t want to do by threatening or hurting him/her? Do you ever pick on anyone? |

Interviewer begins with standard questions, but may ask additional questions to ensure that the definition is met in full. Furthermore, interviewer asks who the perpetrator was (sibling or peers). Only peer bullying coded for this study. Frequency and onset are also assessed.

Assessment of Adult Outcomes

All outcomes except officially recorded criminal offenses were assessed through interviews with the young adults with the Young Adult Psychiatric Assessment (YAPA) (Angold, Erkanli et al. 2012)). The four broad domains were:

Health

Participants reported being diagnosed with a serious physical illness or being in a serious accident at any point during young adulthood or having a sexually transmitted disease (report of testing positive for herpes, genital warts, chlamydia, or HIV). Weight and height measurements were used to derive body mass index with obesity defined as a BMI value greater than or equal to 30 kg/m2. Participants were assessed for a DSM-IV psychiatric diagnosis (any DSM-IV anxiety disorder, any depressive disorder, and antisocial personality disorder). Regular smoking was defined as smoking > 1 cigarette per day for 3 months. Self-reported perceived poor health, high illness contagion risk, and slow illness recovery was derived from a physical health problems survey (Form HIS-1A (1998), US Department of Commerce for the U.S. Public Health Service).

Risky/illegal behaviors

Official felony charges were harvested from North Carolina administrative Offices of the Courts records. Self-report was used to assess recent police contact, often lying to others, frequent physical fighting, breaking into another home/business/property, frequent drunkenness (drinking to excess at least once weekly for 3 months), recent use of marijuana or other illegal substances and one-time sexual encounters with strangers (hooking up with strangers).

Wealth: Financial/educational accomplishments

Being impoverished was coded based upon thresholds issued by the Census Bureau based on income and family size (Dalaker and Naifah 1993). High school dropout and completion of any college education were coded based upon the subject’s educational status at the last adult assessment. Job problems were assessed as being dismissed or fired from a job and quitting a job without financial preparations. Finally, other financial problems assessed included: failing to honor debts or financial obligations and being a poor manager of one’s finances.

Social relationships

Marital, parenthood, and divorce status were determined through self-report at the last adult assessment. The quality of the participant’s relationship with their parents, spouse/significant other, and friends was assessed at each assessment including arguments and violence. Variables were included to indicate any violence in a romantic relationship, a poor relationship with one’s parents, no best friend or confidante, and problems making or keeping friends.

Assessment of Childhood Hardships

Childhood hardships were assessed through the following dichotomized risk scales: low socioeconomic status (SES) (Nakao and Treas 1992), unstable family structure (presence of 2 or more indicators: single parent structure, step-parent in household, divorce, parental separation, or change in parent structure), maltreatment (any: sexual abuse, physical abuse, neglected) and family dysfunction (5 or more of the following: inadequate parental supervision, over-involvement of the parent, physical violence between parents, high frequency of parental arguments, marital relationship characterized by absence of affection, apathy, or indifference, child is upset by or actively involved in arguments between parents, mother scores in elevated range on depression questionnaire, high frequency of arguments between parent and child, and most parental activities are source of tension or worry for the child (see Codebooks for all items: http://devepi.duhs.duke.edu/codebooks.html).

Childhood Psychiatric Problems

Childhood psychiatric variables were assessed between 9–16 years of age (Costello, Mustillo et al. 2003) and included the following DSM-IV diagnoses: any anxiety disorder, depressive disorders (same as adulthood), disruptive behavior disorders (including conduct disorder, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, and oppositional defiant disorder) and substance disorder (including any abuse/dependence).

Analyses

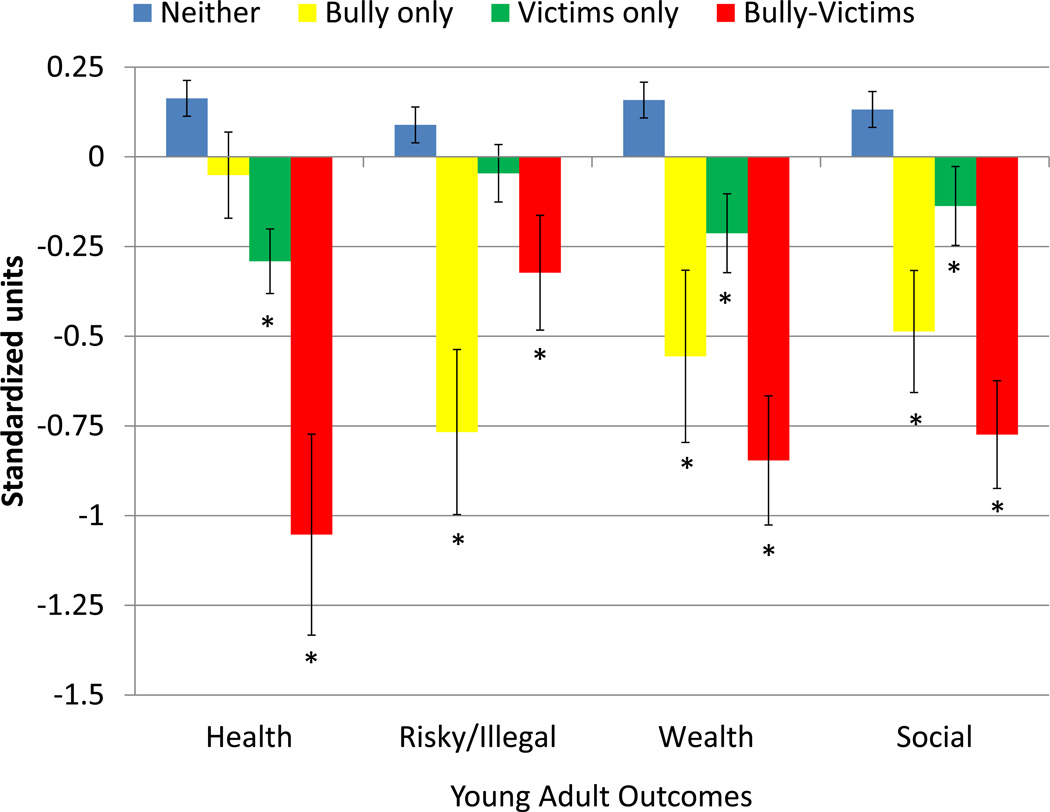

All associations were tested using weighted regression models in a generalized estimating equations framework implemented by SAS PROC GENMOD. Robust variance (sandwich type) estimates were used to adjust the standard errors of the parameter estimates for the sampling weights applied to observations. Bullies, victims and bully/victims were compared to those not involved in any bullying (neither) in childhood. Negative primary outcomes were aggregated across each of the four domains (health, risky/illegal behaviors, wealth: financial/educational, and social functioning) and these scales were standardized (Mean: 0; SD: 1; i.e. the mean of 0 indicates the mean problems for each domain in the total sample). Bully/victim status predicted standardized domain scores in a series of weighted linear regression models (figure 2). For follow-up bivariate analyses of individual indicators within the four broad domains, logistic regression was used and odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals are reported (table 2 and table 3). Multivariable analyses in table 4 involved prediction of young adult outcome variables by bully/victim status controlling for childhood psychiatric variables and hardships that could have occurred prior to, concurrent with, or after the first reported incident of bullying role involvement. Finally, in table 5 the unadjusted and adjusted associations of one timepoint and chronic victimization versus neither (not involved in bullying) for each of the domains in adulthood are reported.

Figure 2.

Table 2.

Associations between role in bullying in childhood and young adult health functioning and risky/illegal behaviors

| Neither | Bully only |

Victim only |

Bully/ Victim |

Bully vs. Neither |

Victim vs. Neither |

Bully-victim vs. Neither |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Outcomes | N=887 | N=112 | N=335 | N=86 | OR (95%CI) | p value | OR (95%CI) | p value | OR (95%CI) | p value |

| Serious Illness | 3.2 | 3.4 | 7.7 | 16.7 | 1.06 (0.35–3.18) | 0.9171 | 2.52 (0.93–6.84) | 0.0694 | 6.02 (1.62–22.33) | 0.0073 |

| Serious Accident | 11.7 | 6.5 | 17.1 | 7.0 | 0.53 (0.24–1.18) | 0.1198 | 1.56 (0.83–2.93) | 0.1682 | 0.57 (0.25–1.31) | 0.1865 |

| Sexually transmitted disease | 4.8 | 7.0 | 5.2 | 10.6 | 1.51 (0.63–3.63) | 0.355 | 1.10 (0.40–3.05) | 0.851 | 2.37 (0.65–8.58) | 0.189 |

| Obesity | 26.1 | 32.9 | 27.1 | 35.6 | 1.39 (0.63–3.05) | 0.417 | 1.05 (0.66–1.68) | 0.841 | 1.56 (0.70–3.49) | 0.275 |

| Any non-substance psychiatric disorder | 14.2 | 27.5 | 34.0 | 52.4 | 2.28 (1.02–5.08) | 0.044 | 3.11 (1.86–5.20) | 0.000 | 6.62 (2.89–15.16) | 0.000 |

| Regular smoking (>1day) | 36.6 | 55.4 | 52.1 | 79.0 | 2.16 (1.01–4.60) | 0.047 | 1.89 (1.20–2.96) | 0.006 | 6.52 (2.79–15.22) | 0.000 |

| Self-report of poor health | 15.1 | 11.7 | 23.2 | 36.9 | 0.74 (0.38–1.46) | 0.389 | 1.69 (0.97–2.96) | 0.064 | 3.28 (1.33–8.09) | 0.010 |

| Self-report of illness contagion | 21.4 | 22.7 | 31.6 | 48.3 | 1.07 (0.43–2.67) | 0.876 | 1.70 (1.04–2.76) | 0.034 | 3.42 (1.50–7.82) | 0.004 |

| Self-report of slow illness recovery | 7.1 | 3.6 | 8.8 | 31.5 | 0.49 (0.18–1.34) | 0.162 | 1.26 (0.57–2.76) | 0.570 | 6.03 (2.15–16.93) | 0.001 |

| Risky/Illegal behaviors | ||||||||||

| Official felony charge | 9.7 | 22.0 | 11.1 | 27.1 | 2.63 (1.22–5.70) | 0.014 | 1.17 (0.63–2.17) | 0.620 | 3.48 (1.33–9.06) | 0.011 |

| Police contact | 11.2 | 22.4 | 9.8 | 20.7 | 2.29 (0.94–5.59) | 0.068 | 0.86 (0.42–1.78) | 0.689 | 2.07 (0.69–6.21) | 0.196 |

| Lying | 3.9 | 9.3 | 3.2 | 4.2 | 2.52 (0.63–10.08) | 0.191 | 0.82 (0.27–2.50) | 0.729 | 1.07 (0.36–3.19) | 0.910 |

| Physical fighting | 6.4 | 14.0 | 7.0 | 15.6 | 2.39 (0.86–6.64) | 0.095 | 1.10 (0.53–2.30) | 0.799 | 2.71 (0.89–8.28) | 0.079 |

| Breaking in | 3.2 | 12.4 | 3.4 | 16.6 | 4.28 (1.33–13.72) | 0.014 | 1.05 (0.35–3.15) | 0.925 | 6.03 (1.65–21.98) | 0.007 |

| Frequently drunk | 8.5 | 24.8 | 10.4 | 5.9 | 3.57 (1.37–9.30) | 0.009 | 1.26 (0.59–2.68) | 0.545 | 0.68 (0.28–1.67) | 0.402 |

| Marijuana use | 28.1 | 58.7 | 38.2 | 40.0 | 3.64 (1.73–7.65) | 0.001 | 1.58 (0.99–2.52) | 0.057 | 1.70 (0.75–3.89) | 0.206 |

| Other illicit drug use | 8.1 | 25.3 | 9.7 | 10.6 | 3.86 (1.53–9.73) | 0.004 | 1.23 (0.59–2.55) | 0.581 | 1.35 (0.62–2.96) | 0.451 |

| Hooking up with stranger | 12.1 | 25.9 | 19.0 | 8.0 | 2.54 (1.02–6.34) | 0.046 | 1.70 (0.90–3.24) | 0.104 | 0.63 (0.28–1.41) | 0.262 |

Bolded ORs significant at p<0.05.THC=Marijuana-related. OR = odds ratio; 95%CI=95 percent confidence interval.

Table 3.

Associations between role in bullying in childhood and young adult financial and social functioning

| Neither | Bully only |

Victim only |

Bully/ Victim |

Bully vs. Neither |

Victim vs. Neither |

Bully-victim vs. Neither |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wealth: Financial/ educational functioning | N=887 | N=112 | N=335 | N=86 | OR (95%CI) | p value | OR (95%CI) | p value | OR (95%CI) | p value |

| Impoverished | 18.3 | 32.4 | 29.9 | 38.2 | 2.14 (0.99–4.62) | 0.052 | 1.91 (1.15–3.17) | 0.013 | 2.76 (1.17–6.55) | 0.021 |

| No high school diploma | 18.6 | 26.3 | 20.1 | 41.1 | 1.56 (0.78–3.11) | 0.208 | 1.10 (0.67–1.80) | 0.701 | 3.05 (1.36–6.83) | 0.007 |

| No college | 43.7 | 62.2 | 53.3 | 70.7 | 2.12 (1.03–4.36) | 0.042 | 1.47 (0.97–2.24) | 0.073 | 3.11 (1.33–7.30) | 0.009 |

| Dismissed from a job | 20.2 | 38.6 | 33.5 | 38.1 | 2.49 (1.16–5.31) | 0.019 | 1.99 (1.23–3.21) | 0.005 | 2.43 (1.06–5.61) | 0.037 |

| Quit multiple jobs | 9.9 | 27.8 | 20.3 | 37.3 | 3.51 (1.43–8.62) | 0.006 | 2.33 (1.28–4.26) | 0.006 | 5.44 (2.28–12.96) | 0.000 |

| Failing to honor financial obligations | 10.7 | 30.5 | 9.9 | 35.8 | 3.66 (1.46–9.21) | 0.006 | 0.92 (0.46–1.86) | 0.819 | 4.65 (1.86–11.62) | 0.001 |

| Poor financial management | 7.4 | 11.2 | 16.1 | 12.3 | 1.57 (0.49–5.01) | 0.448 | 2.39 (1.24–4.64) | 0.010 | 1.75 (0.52–5.86) | 0.367 |

| Social functioning | ||||||||||

| Violent relationships | 4.9 | 15.3 | 5.0 | 11.1 | 4.48 (1.29–15.53) | 0.0179 | 1.31 (0.60–2.87) | 0.5008 | 3.12 (0.90–10.78) | 0.0728 |

| Poor relationship with parents | 15.0 | 26.6 | 27.3 | 51.9 | 2.05 (0.76–5.53) | 0.154 | 2.12 (1.17–3.83) | 0.013 | 6.10 (2.41–15.41) | 0.000 |

| No best friend/confidante | 23.6 | 38.5 | 24.0 | 46.1 | 2.03 (0.96–4.30) | 0.0652 | 0.95 (0.58–1.56) | 0.842 | 2.77 (1.22–6.28) | 0.0151 |

| Problems making/keeping friends | 2.0 | 16.9 | 8.4 | 10.4 | 6.79 (2.02–22.80) | 0.0020 | 3.08 (1.20–7.93) | 0.0194 | 3.90 (1.03–14.78) | 0.0455 |

Bolded ORs significant at p<0.05.THC=Marijuana-related. OR = odds ratio; 95%CI=95 percent confidence interval.

Table 4.

Associations between role in bullying in childhood and young adult outcomes accounting for childhood family hardships and childhood psychiatric problems

| Bullies vs. Neither | Victims vs. Neither | Bully-Victims vs. Neither | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (SE) | p value | Sig. Covariates |

β (SE) | p value | Sig. Covariates |

β (SE) | p value | Sig. Covariates |

|

| Health | 0.10 (0.15) | 0.49 | 1,2,6,8 | −0.36 (0.10) | <0.001 | 1,2,5,6 | −0.65 (0.28) | <0.05 | 1,2,6 |

| Risky/Illegal | −0.31 (0.24) | 0.20 | 1,7,8,9 | −0.06 (0.10) | 0.52 | 1,8,9 | 0.40 (0.18) | 0.02 | 1,8,9 |

| Wealth: Financial/Educational | −0.21 (0.22) | 0.34 | 1,2,5,8 | −0.21 (0.10) | <0.05 | 1,2,5 | −0.43 (0.18) | <0.05 | 1,2,5 |

| Social | −0.20 (0.18) | 0.28 | 6 | −0.25 (0.12) | <0.05 | 1 | −0.42 (0.18) | <0.05 | 2,6,9 |

Bolded ORs significant at p<0.05.Childhood/adolescent confounders: 1=Sex; 2 = Low SES; 3 = Family instability; 4 = Family dysfunction; 5 = Maltreatment; 6= childhood depression; 7 = childhood anxiety; 8 = childhood disruptive behavior disorders; and 9 = childhood substance disorders.

Table 5.

Raw and adjusted associations between bullying victimization reported once or at multiple assessments in childhood and young adult outcomes

| One timepoint vs. Neither | Chronic vs. Neither | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (SE) | p value | β (SE) | p value | |

| Health | ||||

| Raw | −0.58 (0.12) | <0.0001 | −0.50 (0.18) | 0.005 |

| Adjusted | −0.42 (0.12) | 0.0005 | −0.24 (0.15) | 0.11 |

| Risky/Illegal | ||||

| Raw | −0.09 (0.11) | 0.39 | −0.14 (0.14) | 0.31 |

| Adjusted | −0.00 (0.11) | 0.93 | 0.13 (0.14) | 0.39 |

| Wealth: Financial/Educational | ||||

| Raw | −0.30 (0.12) | 0.011 | −0.68 (0.20) | 0.0005 |

| Adjusted | −0.03 (0.11) | 0.77 | −0.42 (.21) | 0.050 |

| Social | ||||

| Raw | −0.25 (0.11) | 0.030 | −0.71 (0.21) | 0.0008 |

| Adjusted | −0.10 (0.11) | 0.39 | −0.44 (0.21) | 0.034 |

Bolded ORs significant at p<0.05.Adjusted analyses controlled for the following childhood/adolescent confounders: sex, low SES, family instability, family dysfunction, maltreatment, childhood depression, childhood anxiety, childhood disruptive behavior disorders, and childhood substance disorders.

Results

Bullying role in childhood and specific aspects of health and risky behavior in adulthood

Table 2 displays the unadjusted associations between childhood role status in bullying and adult health outcomes and risky/illegal behaviors. Each association was tested with weighted logistic regression models and associations are reported as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals and associated p values compared to the neither group. Bully-victims in school had the worst health outcomes in adulthood (elevated on 6 of 9 indices), with marked elevation for having been diagnosed with a serious illness, having been diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder, regular smoking and slow illness recovery. Bullies and victims were both elevated on 2 of 9 indices - psychiatric problems and regular smoking. Risky/illegal behaviors were elevated for bullies (6 of 9 indices) and bully-victims (2 of 9 indices). Bullies were elevated for a range of behaviors including both official felony charges, substance use, and self-report of illegal behavior. There was no evidence of elevated risk for risky/illegal behavior for victims.

Bullying role in childhood and specific aspects of wealth and social relationships in adulthood

Unadjusted associations were also tested for wealth (financial/educational) and social outcomes (table 3). The area with the most evidence of impairment across all groups was financial/educational functioning. Bullies were elevated on 5 of 7 outcomes, bully-victims were elevated on 6 outcomes and victims were elevated on 4 outcomes. All groups were at risk for being impoverished in young adulthood and having difficulty keeping jobs. Both bullies and bully-victims displayed impaired educational attainment. There were no significant differences across groups in the likelihood of being married, having kids or being divorced, but social relationships were disrupted for all groups.

Overall effect of bullying role on health, risky behavior, wealth and social relationships in adulthood

Figure 2 displays unadjusted z scores for each of the four outcome domains for all groups. Across all domains, positive scores indicate fewer problems and negative scores indicate more problems. Asterisks indicate whether a bullying involvement group was statistically different relative to the neither group (p<.05). The weighted linear regression coefficients (β) are provided in the Figure 2 legend. Bully-victims were elevated across all domains and both bullies and victims were elevated across three of the four domains.

Bullying role in childhood and adult outcomes adjusted for childhood psychiatric problems and family hardship

These associations, however, might be accounted for by family hardships and psychiatric problems in childhood that both influenced or were concurrent with risk for bullying or victimization. All significant associations were retested accounting for childhood family hardships (family SES, family stability, family dysfunction, and maltreatment) and child psychiatric problems (childhood depression; childhood anxiety; childhood disruptive behavior disorders; childhood substance disorders). Bullies were no longer at risk for any adult outcomes after adjusting for confounders. In contrast, being a victims or bully-victims continued to be associated with poor outcomes in adulthood (see table 4). Being a victim and, in particular, a bully-victim continued to be an independent predictor of diminished health, wealth and social relationships in adulthood. Bullying involvement did not predict risky/illegal behavior in adjusted models.

Chronicity of peer victimization and adult outcomes

Of the 421 victims or bully-victims, 159 (37.8%) were chronically bullied. Table 5 compares those who were victims at one timepoint only or at 2 or more timepoints (chronic victims) to those with no bullying involvement in all outcome domains. The findings are consistent with a dose-response pattern of effect of being bullied and wealth and social relations in adulthood. After adjustments for confounders, those who were chronically bullied continued to be more likely to have wealth (financial/educational) and social relationship problems. In direct comparisons of the chronic to one time point victims (not shown), the chronically bullied had significantly higher levels of social problems (p=.046) and showed a trend towards higher wealth problems (p=.083). There was no evidence of difference between groups on risky/illegal behavior or health outcomes.

Discussion

Involvement in any role in bullying was predictive of compromised adult health, wealth, risky/illegal behavior and social relationships. Once adjusted for family hardship and childhood psychiatric disorders, victims and bully-victims continued to be impaired in health, wealth and social relationships in adulthood. The greatest impairment across multiple areas of adult functioning was found for bully-victims. In contrast, pure bullies were not at increased risk of poor adult outcome once other family and childhood risk factors were taken into account. Finally, there was evidence to support a dose-response effect of being bullied for poor wealth and social outcomes.

Previous longitudinal research has suggested that victimization or bullying perpetration in childhood may be a marker of present and later psychopathology rather than a cause of long term adverse outcome (Sourander, Ronning et al. 2009). Other short term longitudinal studies suggested that the effects of victimization are unique and occur over and above any pre-existing behavior or emotional problems (Kim, Leventhal et al. 2006) or genetic liability (Arseneault, Milne et al. 2008). Previous cross-sectional studies or short term longitudinal studies in childhood (Zwierzynska, Wolke et al. ; Arseneault, Bowes et al. 2010) or retrospective studies in adulthood (Lund, Nielsen et al. 2009) indicated the presence of more physical, psychosomatic or mental health problems in victimised children and, in particular, those who were bully-victims. It has been suggested that bullying others may be, for some children, a response to being bullied, rather than the result of bullies becoming targets of other bullies (Arseneault, Bowes et al. 2010). This move from victim to bully-victim may occur more often when victims are from deprived families, show poor emotional regulation or have mental health problems and lack resources to deal with the stress. Indeed, victims have been described as withdrawn, unassertive, easily emotionally upset, and as having poor emotion or social understanding (Camodeca, Goossens et al. 2003; Woods, Wolke et al. 2009), whereas bully-victims tend to be aggressive, easily angered, and frequently bullied by their siblings (Wolke and Skew 2012). In the present study, victims and particularly bully-victims differed from children not involved in bullying by growing up more often in deprived families and having more mental health problems in childhood. By adjusting for these pre-existing or concurrent problems, this study provides strong evidence of unique and direct effects, not only on health but also wealth (Brown and Taylor 2008) and social functioning in adulthood, of exposure to peer victimization, and in particular, being victimized by peers chronically or being a bully-victim (Lehti, Klomek et al. 2012). Controlling for family and childhood psychiatric problems attenuated these relationships but did not eliminate them.

In contrast, risky/illegal behaviors ranging from felony charges to illicit drug use or hooking up with strangers were attenuated and no longer explained by involvement in bullying once family and child psychiatric factors were adjusted for. Boys and those with childhood disruptive disorders (including conduct disorder, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, and oppositional defiant disorder) and childhood substance disorder were more likely to engage in risky/illegal behaviors. Thus risky/illegal behaviour into adulthood was explained, not by bullying or victimization per se, but by a persistent overall antisocial tendency (Odgers, Moffitt et al. 2008) where bullying involvement as perpetrator may be an early indicator rather than a cause (Niemelä, Brunstein-Klomek et al. 2011). Similarly, a recent meta-analysis found that bullying perpetration was related to later offending, but that the size of this effect decreased as more confounders were included in the analysis and follow-up periods increased (Ttofi, Farrington et al. 2011).

There are a variety of potential routes by which being victimized may affect later life outcomes. Being bullied may alter physiological responses to stress (Ouellet-Morin, Danese et al. 2011), interact with a genetic vulnerability such as variation in the serotonin transporter (5-HTT) gene (Sugden, Arseneault et al. 2010), affect telomere length or the epigenome (Shalev, Moffitt et al. 2012), by changing cognitive responses to threatening situations (Mezulis, Abramson et al. 2004) or by affecting school performance. Altered HPA-axis activity and altered cortisol responses may not only increase the risk for developing mental health problems (Harkness, Stewart et al. 2011) but increase susceptibility to illness by interfering with immune responses (Segerstrom and Miller 2004). Both altered stress responses and altered social cognition (e.g. being hypervigilant to hostile cues (van Dam, van der Ven et al. 2012)) and neuro-circuitry (Teicher, Samson et al. 2010) related to bullying exposure may affect social relationships with parents, friends and co-workers. Finally, victimization, in particular of bully-victims, has been found to be associated with poor concurrent academic achievement (Nakamoto and Schwartz 2010). However, for victims this association is usually weak. Indeed we found no increased risk of failure to complete high school or college for victims but increased overall financial and educational problems for chronic victims. Similarly, bully-victims were at higher risk for school failure and poor job performance. This is in contrast to a previous report that, however, did not distinguish between victims and bully-victims but looked at them together as victims (Brown and Taylor 2008).

Caveats

This study has the advantages of a prospective, longitudinal design within a representative community sample that used structured interviews to assess childhood bullying involvement and young adult outcomes. This sample is not representative of the US population with American Indians overrepresented and African-Americans underrepresented. The prevalence rates of bullying and peer victimization reported in childhood are similar to rates reported in population-based studies (Nansel, Overpeck et al. 2001) (Analitis, Velderman et al. 2009). Bullying involvement was coded by aggregating across multiple observations. For the bully-victim group, this might mean that participants moved between the victim and bully role across time (Arseneault, Bowes et al. 2010). It is not at all clear how different patterns of movement between victimization and bullying might affect short- or long-term outcomes (van Dam, van der Ven et al. 2012). Family hardships and childhood psychiatric problems were assessed throughout childhood and adolescence and accounted for in adjusted analysis. It is possible that psychiatric problems, in particular, might have been the consequence of bullying involvement in some cases (Arseneault, Milne et al. 2008; Reijntjes, Kamphuis et al. 2010) rather than a confounder as in the analysis. This would suggest that our findings may underestimate the long-term effects of bullying role. There is always the possibility of unmeasured confounding in longitudinal research such as potential genetic factors. Finally, despite the use of a large community sample, there were not sufficient participants in some groups to allow us to test differences by race/ethnicity or sex.

Conclusion

Being bullied is not a harmless rite of passage or an inevitable part of growing up but throws a long shadow over affected children’s lives. Victims, in particular chronic victims and bully-victims are at increased risk for adverse health, wealth and social functioning in adulthood. These problems are associated with great costs for the individual and society. Bullying involvement can be easily assessed and monitored by health professionals and school personnel, and effective interventions that reduce victimization are available (Ttofi and Farrington 2011). Such interventions are likely to reduce human suffering and long term health and social costs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The work presented here was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (MH63970, MH63671, MH48085), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA/MH11301), NARSAD (Early Career Award to WC), the William T Grant Foundation and the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) in the UK (ES/K003593/1). We would like to thank Saverio Stranges for comments on an earlier draft.

Footnotes

Authorship

DW and WC developed the study idea. All authors contributed to the study design. Data collection was supervised by AA, EC and WC. Data analysis and interpretation were conducted by WC and DW. DW and WC drafted the paper, and AA and EC provided critical revisions. All authors approved the final version of the paper for submission.

Financial Disclosures

None of the authors have potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH, et al. Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: Implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;101:213–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Analitis F, Velderman MK, et al. Being Bullied: Associated Factors in Children and Adolescents 8 to 18 Years Old in 11 European Countries. Pediatrics. 2009;123(2):569–577. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello E. The Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA) Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:39–48. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello EJ. A test-retest reliability study of child-reported psychiatric symptoms and diagnoses using the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA-C) Psychological Medicine. 1995;25:755–762. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700034991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Erkanli A, et al. Psychiatric Diagnostic Interviews for Children and Adolescents: A Comparative Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;51(5):506–517. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arseneault L, Bowes L, et al. Bullying victimization in youths and mental health problems: "Much ado about nothing"? Psychological Medicine. 2010;40(5):717–729. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arseneault L, Milne BJ, et al. Being Bullied as an Environmentally Mediated Contributing Factor to Children’s Internalizing Problems: A Study of Twins Discordant for Victimization. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(2):145–150. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S, Taylor K. Bullying, education and earnings: Evidence from the National Child Development Study. Economics of Education Review. 2008;27(4):387–401. [Google Scholar]

- Camodeca M, Goossens FA, et al. Links between social informative processing in middle childhood and involvement in bullying. Aggressive Behavior. 2003;29(2):116–127. [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Angold A, et al. The Great Smoky Mountains Study of Youth: Goals, designs, methods, and the prevalence of DSM-III-R disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53:1129–1136. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830120067012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Mustillo S, et al. Prevalence and Development of Psychiatric Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60(8):837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie J, Widom CSpatz. Long-Term Consequences of Child Abuse and Neglect on Adult Economic Well-Being. Child Maltreatment. 2010;15(2):111–120. doi: 10.1177/1077559509355316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalaker J, Naifah M. Poverty in the United States: 1997. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Current Population Reports: Consumer Income. 1993:60–201. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman A, Joyce R, et al. The long shadow cast by childhood physical and mental problems on adult life. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011;108(15):6032–6037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016970108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness KL, Stewart JG, et al. Cortisol reactivity to social stress in adolescents: Role of depression severity and child maltreatment. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36(2):173–181. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman JJ. Skill Formation and the Economics of Investing in Disadvantaged Children. Science. 2006;312(5782):1900–1902. doi: 10.1126/science.1128898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen J, Graham S, et al. Bullying Among Young Adolescents: The Strong, the Weak, and the Troubled. Pediatrics. 2003;112(6):1231–1237. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.6.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YS, Leventhal BL, et al. School Bullying and Youth Violence: Causes or Consequences of Psychopathologic Behavior? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(9):1035–1041. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.9.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehti V, Klomek AB, et al. Childhood bullying and becoming a young father in a national cohort of Finnish boys. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 2012;53(6):461–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2012.00971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund R, Nielsen KK, et al. Exposure to bullying at school and depression in adulthood: A study of Danish men born in 1953. Eur J Public Health. 2009;19(1):111–116. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckn101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezulis AH, Abramson LY, et al. Is There a Universal Positivity Bias in Attributions? A Meta-Analytic Review of Individual, Developmental, and Cultural Differences in the Self-Serving Attributional Bias. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130(5):711–747. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.5.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamoto J, Schwartz D. Is Peer Victimization Associated with Academic Achievement? A Meta-analytic Review. Social Development. 2010;19(2):221–242. [Google Scholar]

- Nakao K, Treas J. GSS Methodological Report No. 74. Chicago, Illinois: National Opinion Research Center; 1992. The 1989 Socioeconomic Index of Occupations: Construction from the 1989 Occupational Prestige Scores. [Google Scholar]

- Nansel TR, Overpeck M, et al. Bullying Behaviors Among US Youth: Prevalence and Association With Psychosocial Adjustment. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;285(16):2094–2100. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.16.2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemelä S, Brunstein-Klomek A, et al. Childhood bullying behaviors at age eight and substance use at age 18 among males. A nationwide prospective study. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(3):256–260. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odgers CL, Moffitt TE, et al. Female and male antisocial trajectories: From childhood origins to adult outcomes. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20(02):673–716. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D. Annotation: Bullying at school: Basic facts and effects of a school based intervention program. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1994;35(7):1171–1190. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouellet-Morin I, Danese A, et al. A Discordant Monozygotic Twin Design Shows Blunted Cortisol Reactivity Among Bullied Children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50(6):574–582. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.02.015. e573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reijntjes A, Kamphuis JH, et al. Peer victimization and internalizing problems in children: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2010;34(4):244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreier A, Wolke D, et al. Prospective Study of Peer Victimization in Childhood and Psychotic Symptoms in a Nonclinical Population at Age 12 Years. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(5):527–536. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segerstrom SC, Miller GE. Psychological Stress and the Human Immune System: A Meta-Analytic Study of 30 Years of Inquiry. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;30(4):601–630. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.4.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalev I, Moffitt TE, et al. Exposure to violence during childhood is associated with telomere erosion from 5 to 10 years of age: a longitudinal study. Mol Psychiatry. 2012 doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sourander A, Brunstein Klomek A, et al. Bullying at age eight and criminality in adulthood: findings from the Finnish Nationwide 1981 Birth Cohort Study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2011;46(12):1211–1219. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0292-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sourander A, Ronning J, et al. Childhood Bullying Behavior and Later Psychiatric Hospital and Psychopharmacologic Treatment: Findings From the Finnish 1981 Birth Cohort Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(9):1005–1012. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugden K, Arseneault L, et al. Serotonin Transporter Gene Moderates the Development of Emotional Problems Among Children Following Bullying Victimization. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49(8):830–840. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton J, Smith PK, et al. Bullying and ‘theory of mind’: A critique of the ‘social skills deficit’ view of anti-social behaviour. Social Development. 1999;8(1):117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Teicher MH, Samson JA, et al. Hurtful Words: Association of Exposure to Peer Verbal Abuse With Elevated Psychiatric Symptom Scores and Corpus Callosum Abnormalities. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167(12):1464–1471. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10010030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ttofi MM, Farrington DP. Effectiveness of school-based programs to reduce bullying: a systematic and meta-analytic review. Journal of Experimental Criminology. 2011;7(1):27–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ttofi MM, Farrington DP, et al. The predictive efficiency of school bullying versus later offending: A systematic/meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 2011;21(2):80–89. doi: 10.1002/cbm.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dam DS, van der Ven E, et al. Childhood bullying and the association with psychosis in non-clinical and clinical samples: a review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine. 2012;42(12):2463–2474. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winsper C, Lereya T, et al. Involvement in Bullying and Suicide-Related Behavior at 11 Years: A Prospective Birth Cohort Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;51(3):271–282. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.01.001. e273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolke D, Skew A. Family Factors, Bullying Victimisation & Wellbeing in Adolescents. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies. 2012;3(1):101–119. [Google Scholar]

- Wolke D, Woods S, et al. The association between direct and relational bullying and behaviour. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2000;41(8):989–1002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolke D, Woods S, et al. Bullying involvement in primary school and common health problems. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2001;85:197–201. doi: 10.1136/adc.85.3.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolke D, Woods S, et al. Who escapes or remains a victim of bullying in primary school? British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2009;27:835–851. doi: 10.1348/026151008x383003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods S, Wolke D, et al. Emotion recognition abilities and empathy of victims of bullying. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2009;33(5):307–311. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwierzynska K, Wolke D, et al. Peer Victimization in Childhood and Internalizing Problems in Adolescence: A Prospective Longitudinal Study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. :1–15. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9678-8. Early view. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.