Abstract

Cocaine abuse and addiction remain great challenges on the public health agendas in the U.S. and the world. Increasingly sophisticated perspectives on addiction to cocaine and other drugs of abuse have evolved with concerted research efforts over the last 30 years. Relapse remains a particularly powerful clinical problem as, even upon termination of drug use and initiation of abstinence, the recidivism rates can be very high. The cycling course of cocaine intake, abstinence and relapse is tied to a multitude of behavioral and cognitive processes including impulsivity (a predisposition toward rapid unplanned reactions to stimuli without regard to the negative consequences), and cocaine cue reactivity (responsivity to cocaine-associated stimuli) cited as two key phenotypes that contribute to relapse vulnerability even years into recovery. Preclinical studies suggest that serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine; 5-HT) neurotransmission in key neural circuits may contribute to these interlocked phenotypes well as the altered neurobiological states evoked by cocaine that precipitate relapse events. As such, 5-HT is an important target in the quest to to understand the neurobiology of relapse-predictive phenotypes, to successfully treat this complex disorder and improve diagnostic and prognostic capabilities. This review emphasizes the role of 5-HT and its receptor proteins in key addiction phenotypes and the implications of current findings to the future of therapeutics in addiction.

Keywords: Addiction, Cocaine, Cue Reactivity, Dependence, Impulsivity, Serotonin

1. Introduction

Thirty years of intensive study have elucidated molecular mechanisms underlying the in vivo effects of abused substances, the impressive, distributed network of circuitry at the heart of addictive processes, and have made inroads into the complex polygenetic nature of addiction (Ducci and Goldman, 2012; Kalivas and Volkow, 2005; Koob and Volkow, 2010). These 30 years have produced increasingly sophisticated perspectives on addiction as a chronic, relapsing brain disorder that engages reward function and an `expanding cycle of dysfunction' in cognition, learning and emotional functions (Volkow, et al., 2010). This trajectory from drug use to addiction begins against a background of vulnerability based upon genetic and environmental factors, and progresses as neuronal plasticity in key brain circuits entrains addictive behaviors in concert with experiential learning and the added pharmacological impact of the abused substance. The means to reverse causal neuroplasticity and therapeutically improve function in the addicted brain is an important quest and one ripe with near-term therapeutic potential with positive outcomes. Although surprisingly less is known about its influence compared to key players dopamine (DA) and glutamate (Kalivas and Volkow, 2005), serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine; 5-HT) neurotransmission in key neural circuits may contribute to inherent states of vulnerability as well as the altered neurobiological states that drive the transition from drug use to abuse to dependence. This review emphasizes the role of 5-HT in key addiction phenotypes and the implications of current findings to the future of therapeutics in addiction.

There are a multitude of factors that contribute to the initial decision to experience an abused drug, to the continued maintenance of drug use and the ultimate development of dependence or addiction. The same or even different factors may contribute to vulnerability to withdrawal-related syndromes, difficulty achieving abstinence, and sensitivity to relapse during abstinence. Relapse is a particularly challenging clinical problem as, even though a drug abuser may initiate termination of drug use and commit to abstinence, the recidivism rates can be very high (Brandon, et al., 2007). Relapse is defined as reversion to drug-using behavior which interrupts the progress of abstinence and can be seen as a dynamic process rather than a single, discrete event (Maisto and Connors, 2006; Miller, et al., 1996). Vulnerability to endogenous factors (e.g., craving, stress, withdrawal) are interwoven with responsiveness to exogenous stimuli (e.g., drug-associated cues) which can serve as immediate antecedents to relapse (Hendershot, et al., 2011). Efficacious relapse prevention programs emphasize cognitive-behavioral skills and coping responses with an accent on environmental stimuli and cognitive processes as triggers (Hendershot, et al., 2011). Medications are also useful to suppress relapse which requires reestablishment of normal brain function consequent to long-term, drug-induced neuroplasticity and diminishment of the power of relapse triggers (Modesto-Lowe and Kranzler, 1999; Paterson, 2011). Currently, medications for treatment of opioid (heroin, morphine) and alcohol addiction which help to suppress relapse in the context of behavioral therapy have been developed. However, although nicotine replacement therapy, buproprion and varenicline are effective therapeutics for nicotine addictions, medication development efforts have not yet yielded effective pharmacotherapies for cocaine and other abused psychostimulants. A great deal of interest remains in filling this gap to maximize the probability of treatment success by minimizing lapses to drug use (Hendershot, et al., 2011;Volkow and Skolnick, 2012).

2. Cocaine

The illicit abuse of psychostimulants is a problem that includes a myriad of abused chemical substances. The present review will focus on cocaine for several reasons. First, cocaine remains one of the greatest challenges on the public health agendas in the U.S. and the world. Indicators of the extent of the cocaine problem in the U.S. (e.g., forensic seizures, treatment, mortality and emergency department admissions) continue to dominate the landscape; serious health and social consequences of cocaine use extensively impact families and communities and drain their resources (Community Epidemiology Work Group, 2005). There were ~1.4 million current cocaine users aged 12 or older in the U.S. in 2011 (SAMHSA, 2012); 50% of the four million drug-related emergency department visits in 2010 involved illicit drug use and cocaine was cited as the abused drug most commonly-involved (DAWN: Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2013). While treatment has been shown to decrease morbidity and mortality associated with this disorder, only ~11% of those who needed treatment received care in 2009, with cost and inaccessibility cited as primary barriers (Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University, 2012). Second, there is a wealth of epidemiological knowledge that attests to the tenacity of cocaine abuse in those who suffer its vagaries (Degenhardt and Hall, 2012; Schulden, et al., 2009) as well as basic and translational research in both clinical populations and animal models (Kalivas and Volkow, 2005; Koob and Volkow, 2010). Lastly, this rich database provides a knowledge scaffold upon which to disentangle the role of 5-HT in key facets of cocaine addiction and to ultimately integrate this knowledge into the dominant theoretical constructs of addiction (Kalivas and Volkow, 2005; Koob and Volkow, 2010). Thus, the impact of cocaine abuse and dependence on the quality of health and society is massive, and the lack of useful therapeutic medications to suppress intake and enhance recovery in cocaine dependence is considered a major unaddressed gap (Hendershot, et al., 2011;Volkow and Skolnick, 2012).

The cycling course of cocaine intake, abstinence and relapse is tied to a multitude of behavioral and cognitive processes with impulsivity and cue reactivity cited as two key phenotypes that set up vulnerability to relapse even years into recovery (Drummond, 2001; Koob and Volkow, 2010; Moeller, et al., 2001b; O'Brien, et al., 1998; Saunders, et al., 2013). Impulsivity has been defined clinically as a predisposition toward rapid unplanned reactions to stimuli without regard to the negative consequences (Moeller, et al., 2001a), while cue reactivity is conceptualized as the sensitivity to cues linked with the drug-taking experience that are known to trigger craving in humans (Carter and Tiffany, 1999; O'Brien, et al., 1988; O'Brien, et al., 1998). Inherent (trait) impulsivity and the incentive motivation for drug and drug-associated cues are woven in a complex web of cause and effect. Cocaine-dependent subjects are more impulsive than non-drug using subjects on both self-report questionnaires and laboratory measures of impulsivity (Moeller, et al., 2001a; Moeller, et al., 2001b). Furthermore, greater impulsivity predicts reduced retention in outpatient treatment trials for cocaine dependence (Green, et al., 2009; Moeller, et al., 2001b; Moeller, et al., 2007; Patkar, et al., 2004; Schmitz, et al., 2009). High impulsivity has been noted in cocaine-dependent subjects who express high cocaine cue reactivity (Liu, et al., 2011) and a similar relationship has been observed in cigarette smokers (Doran, et al., 2007; Doran, et al., 2008). Individuals with poor impulse control may be more vulnerable to drug-associated stimuli, and less capable of engaging processes that override heightened attentional biases for cues (Liu, et al., 2011). Interestingly, acute amphetamine administration decreased impulsive choice when the delay to obtain the reinforcer was signaled by a discrete cue (light/tone), but increased impulsive choice in the absence of a paired cue (Cardinal, et al., 2000), further suggesting that impulsivity and cue-associated events are intertwined. Individual differences in reactivity to cues could also be caught in this web, although it is difficult to assess whether there may be “trait” sensitivity to reward-related cues (Mahler and de Wit, 2010) that predates chronic cocaine use. Phenotypic differences in sensitivity to reward-related cues are reported in rats such that the propensity to approach a cue predictive of reward availability (“sign-tracking”) predicts the motivation to self-administer cocaine and to reinstate drug-seeking after extinction from cocaine self-administration relative to rats that preferentially approach the location of the reward delivery (“goal-trackers”) (Saunders and Robinson, 2013; Yager and Robinson, 2013). Interestingly, sign-trackers exhibit higher impulsivity relative to goal-trackers (Flagel, et al., 2010; Tomie, et al., 2008). Thus, there is a growing appreciation that impulsivity and cocaine cue reactivity are interlocked contributors to relapse, a cardinal facet of addiction and may be mediated by shared neurobiology and neuroanatomy.

3. Addiction Neurocircuitry

Addiction is now recognized as a disordered integration of cognitive and motivational aspects of reward-directed behavior involving higher order limbic-corticostriatal circuit structures (Kalivas and Volkow, 2005). This circuit controls both impulsivity and cue reactivity and neuroadaptations in limbic-corticostriatal subnuclei are noted as particularly relevant in addiction (Feil, et al., 2010; Fineberg, et al., 2010; Kalivas and Volkow, 2005; Koob and Volkow, 2010). Several key regions implicated include: (1) ventral tegmental area (VTA), initiation of sensitization (enhanced behavioral responsivity), reward-mediated behaviors, anhedonia of acute withdrawal; (2) medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), inhibitory control, site of action for abused drugs to alter executive function and decision-making; (3) nucleus accumbens (NAc), reward, maintenance of sensitization, persistent drug-induced behaviors; (4) amygdala, memory for motivational impact of drug-associated stimuli) (Everitt and Wolf, 2002; Kalivas and Volkow, 2005; Kelley, 2004).

The complexity of the limbic-corticostriatal circuitry involved in addictive process should not be underestimated, particularly with innervation from all monoamine efferents and extensive reciprocal and looping interconnections with other cortical, limbic, and thalamic nodes. Functional imaging studies conducted in humans are consistent in citing corticostriatal connectivity as critical in impulsivity and cocaine cue reactivity (Chase, et al., 2011; Chikazoe, 2010; Wager, et al., 2005). Exposure to drug-associated cues activates cortical regions such as the anterior cingulate cortex, the orbitofrontal cortex, and the insula in humans (Bechara, 2005; Childress, et al., 1999; Goldstein, et al., 2007; O'Brien, et al., 1988). Further, studies indicate that the inferior, middle and superior frontal gyri in the PFC, orbitofrontal cortex and ventral striatum [caudate, NAc] share increased activation during impulsive action tasks and in response to drug-associated cues (Chase, et al., 2011; Chikazoe, 2010; Wager, et al., 2005). The fact that the impulsive behavior in cocaine-dependent subjects resembles that of patients with PFC lesions (Bechara, et al., 1997) is interesting in light of observations that the PFC has been implicated in cue-elicited cocaine-seeking behaviors (McLaughlin and See, 2003). The mPFC imposes “top down” control of subcortical structures, especially the ventral striatum (NAc) (Dalley, et al., 2011). Compromised signaling between the mPFC and basal ganglia are thought to underlie the cognitive inability to withhold prepotent responses (impulsivity) (Dalley, et al., 2011; Fineberg, et al., 2010), and to maintain abstinence in the face of drug-associated cues in rodents (Kalivas, 2008). Recently, Moeller and colleagues demonstrated differential frontostriatal connectivity features in cocaine-dependent versus non-drug using controls (Ma, et al., 2014). Further, the dorsal prelimbic projection to the NAc core and the ventral infralimbic mPFC projection to the NAc shell (Vertes, 2004) oppositionally control drug-seeking (Di Ciano and Everitt, 2004; Kalivas, 2008; Kalivas and McFarland, 2003; Koya, et al., 2009; McLaughlin and See, 2003; Stefanik, et al., 2013), while the infralimbic mPFC is implicated in impulsive action (Chudasama, et al., 2003; Dalley, et al., 2011; Fineberg, et al., 2010; Murphy, et al., 2012). The normal function of the mPFC microcircuitry is driven by the excitatory and inhibitory balance engendered by glutamate pyramidal neurons and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) interneurons, respectively; alterations in the excitatory/inhibitory balance in the mPFC are hypothesized to drive cognitive deficits in addiction and psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia (O'Donnell, 2011). An elegant study employing novel optogenetic tools recently found that selective activation of glutamate pyramidal neurons in mouse mPFC resulted in deficits in cognitive function while selective activation of GABA interneurons minimally affected behavior; however, activation of GABA interneurons could partially restore the deficits due to activation of glutamate pyramidal neurons (Yizhar, et al., 2011). Thus, there is considerable evidence in support of an imbalance in the limbic-corticostriatal function that may serve an integrating mechanism underlying impulsive action and cue reactivity. While the a priori decision to focus on this circuitry in the present review does not exclude the involvement of a more encompassing neural network over these behaviors, this focus is appropriate for the discussion of 5-HT involvement given its control over critical limbic-corticostriatal circuits (for reviews) (Alex and Pehek, 2006; Bubar and Cunningham, 2008).

4. Serotonin

The 5-HT neurotransmitter system is integral in motor, cognitive, reward and affective function (Jacobs and Fornal, 1995; Lucki, 1998; Soubrié, 1986; Tops, et al., 2009), processes that are under the control of dense 5-HT afferent input to the limbic-corticostriatal circuit afforded by 5-HT neurons originating in the dorsal (DRN) and medial (MRN) raphe nuclei (Kosofsky and Molliver, 1987; Lidov, et al., 1980; Vertes and Linley, 2008). To understand the detailed interactions of 5-HT, 5-HT receptors and drugs of abuse, the picture is astonishingly complex. Serotonin functions within the synapse are controlled by the 5-HT transporter (SERT) while the actions of 5-HT are mediated by 14 genetically-encoded subtypes of 5-HT receptors (5-HTXR), which are grouped into seven families (5-HT1R – 5-HT7R) according to their structural and functional characteristics (for reviews) (Bockaert, et al., 2006; Hoyer, et al., 2002). The 5-HT receptor family is comprised of 13 distinct G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) and one ligand gated ion channel (5-HT3R), providing a diverse landscape of available signaling cascades and mechanisms unparalleled in any other neurotransmitter system. The 5-HT1R (5-HT1AR, 5-HT1BR, 5-HT1DR, 5-HT1ER, 5-HT1FR) couple principally to Gαi/o, the 5-HT2 (5-HT2AR, 5-HT2BR, 5-HT2CR) to Gαq/11, the 5-HT4R, 5-HT6R, and 5-HT7R couple to Gαs while 5-HT5AR couples to Gαi/o; the specific G protein isoform(s) which couples to 5-HT5BR is unknown. An appreciation of the impact of cocaine on 5-HT function must take into consideration the fact that increased synaptic efflux of 5-HT consequent to cocaine-evoked inhibition of 5-HT reuptake would result in 5-HT available for interaction with the regionally-localized receptors, thus, the role of 5-HT in the in vivo effects of cocaine is heavily dependent upon the receptor subtype(s) activated and downstream signaling webs triggered. Experimental approaches that largely stimulate or block multiple 5-HT receptors affords a limited appreciation of the role of 5-HT in neurobiology because these diverse receptors are distributed unevenly in the brain and affect many neural circuits. In fact, we would argue that confusion in our understanding of the relative roles of 5-HT receptors in neurobiology has been perpetrated by the employment of non-selective 5-HT receptor ligands in behavioral and mechanistic studies. A primary consideration is the role of individual 5-HT-receptive proteins in a given brain region, and the balance between facilitatory and inhibitory mechanisms that govern neuronal function and which, in turn, can be altered in long-term cocaine exposure. Serotonin neurotransmission is important in the tonic and phasic control over the limbiccorticostriatal circuit via regulation of both DA and glutamate neurotransmission (for review) (Alex and Pehek, 2006) and perturbations in the balance of its control may contribute to basal states of vulnerability as well as the altered neurobiological states that drive the transition from cocaine use to abuse to dependence.

The current literature supports a role for serotonergic control over impulsivity and cocaine cue reactivity, although there are decided gaps in appreciating how 5-HT systems interdigitate with other neurotransmitters (e.g., dopamine, glutamate) involved in these phenotypes. Here, we review the results of studies which employed global 5-HT manipulations and relatively selective 5-HT receptor ligands across assays that tap into behavioral expression of these constructs. Ultimately, we focus on the involvement of 5-HT2AR and 5-HT2CR systems due to the consistency in experimental outcomes (Table 1). This 5-HT2R family is comprised of the 5-HT2AR, 5-HT2BR and 5-HT2CR that share sequence homology, similar pharmacological characteristics and signaling pathways (Bockaert, et al., 2006; Hoyer, et al., 2002). The ultimate level of functionality of the 5-HT2R is determined by a culmination of factors, including availability of active pools of receptors and effective coupling to and activation of downstream signaling components. Upon the initial event of receptor activation by agonist, both 5-HT2AR and 5-HT2CR interact primarily with the heterotrimeric G protein Gaq/11 to activate the enzyme phospholipase Cβ which generates intracellular second messengers inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate and diacylglycerol, leading to increased calcium release from intracellular stores (Hannon and Hoyer, 2008; Millan, et al., 2008). Both receptors also activate phospholipase A2 and generate arachidonic acid through an (unidentified) pertussis toxin-sensitive G protein (Felder, et al., 1990) as well as phospholipase D (McGrew, et al., 2002; Moya, et al., 2007). Lastly, the 5-HT2AR and 5-HT2CR directly associate with β-arrestin2 to control downstream signaling (Abbas, et al., 2009; Labasque, et al., 2008), a G protein-independent process which has profound behavioral relevance (Schmid, et al., 2008). The degree to which these downstream signaling pathways are recruited varies between the receptors, both at the level of agonist-dependent (“ligand-directed signaling”, “biased agonism”, “functional selectivity”) and agonist-independent activation (“constitutive activity”) of each pathway (Berg, et al., 2005; Berg, et al., 1998). Such features are likely to distinguish the functional effects of the 5-HT2R subtypes and their roles in behaviors key in addictive processes.

Table 1.

Effects of 5-HT manipulations on impulsivity, cocaine reward, and cocaine-seeking in animals

| 5-HT Manipulation | Action | Impulsive Action* | Cocaine Self-Administration* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reward | Cocaine-Seeking | ||||

| Cue | Cocaine | ||||

| 5,7-DHT1–6 | 5-HT neurotoxin |

|

|

|

|

| PCPA6–8 | Tryptophan hydroxylase inhibitor |

|

|

||

| Fenfluramine9–11 | 5-HT releaser |

|

|

NE | |

| Fluoxetine10,12–19 | SSRI |

|

|

|

NE |

| 8-OH-DPAT8,17,21–25 | 5-HT1AR agonist |

|

|

||

| WAY1006358,11,22,23,26 | 5-HT1AR antagonist |

/NE /NE

|

NE |

|

|

| RU249698,23,27 CP9425328 |

5-HT1BR agonist |

/NE /NE

|

|

|

|

| SB216641, GR12793529 | 5-HT1BR antagonist |

|

|

||

| --- | 5-HT1BR overexpression in NAc 30 |

|

|

|

|

| DOI8,21,23,31–35 | 5-HT2AR agonist |

|

|||

| M1009072,36–40 | 5-HT2AR antagonist |

|

NE |

|

|

| RO60-017536,40,49–50 WAY16390941–42,44–45 MK 21249lorcaserin43 |

5-HT2CR agonist |

|

|

|

|

| SB242084^36,40,46, 48-51, 55 | 5-HT2CR antagonist |

|

/NE /NE

|

|

|

| --- | 5-HT2CR knockdown in mPFC 47 |

|

|

||

| SB27014652–54 Ro04-679054 |

5-HT6R antagonist | NE |

/NE /NE

|

|

|

“Impulsive Action” refers to studies that assayed “action restraint” measures of impulsive action, (see text). “Reward” refers to studies that evaluated effects of manipulations predominantly on intake of cocaine (reinforcing effects) and/or breakpoints (motivational effects). “Cocaine-seeking” refers to behavioral output reinforced by contextual and/or discrete drug-associated cues during withdrawal or following repeated extinction training which occurred in the absence (“cue”) or presence of investigator-delivered cocaine (“Cocaine”). Greyed cells indicate that no publications for these manipulations were identified. The red and blue arrows indicate an increase ( ) or decrease (

) or decrease ( ), respectively, in cocaine intake or breakpoint (Cocaine Reward), operant responses following extinction training or forced abstinence in the absence (Cue-Evoked Cue Reactivity) or presence of pretreatment with investigator-delivered cocaine (Cocaine-Primed Cue Reactivity). “NE” indicates that no effect was observed under the treatment conditions employed.

), respectively, in cocaine intake or breakpoint (Cocaine Reward), operant responses following extinction training or forced abstinence in the absence (Cue-Evoked Cue Reactivity) or presence of pretreatment with investigator-delivered cocaine (Cocaine-Primed Cue Reactivity). “NE” indicates that no effect was observed under the treatment conditions employed.

SB242084 alone supported self-administration in squirrel monkeys (Manvich et al., 2012).

2001;

2004;

2003;

2011;

2012;

Recent research emphasizes that the 5-HT system exhibits a multitude of distinctive properties relative to other monoaminergic systems. A new conceptual understanding of 5-HT systems was born with the recent discovery that the synthetic enzyme for 5-HT in brain (tryptophan hydroxylase-2) is structurally distinct from that in peripheral tissues (tryptophan hydroxylase-1) (Walther and Bader, 2003). Not one, but two, serotonergic pathways innervate cortical and subcortical structures from their parent neurons of origin in the raphe nuclei with one set of serotonergic fibers (fine fibers from DRN) exquisitely sensitive and the other (beaded fibers from MRN) relatively insensitive to neurotoxic damage by substituted amphetamines (Kosofsky and Molliver, 1987). The 5-HT2CR is the only GPCR to known to undergo pre-RNA editing such that the 5-HT2CR can exist in 32 predicted mRNA isoforms that could encode up to 24 different receptor protein isoforms in human (Gurevich, et al., 2002) or rat brain (Anastasio, et al., 2014). Constitutive activity for some 5-HT receptors is prominent and the regulation of the 5-HT2R family is unique in that both agonists and antagonists have been noted to downregulate/desensitize receptors, an outcome of chronic treatment which is inconsistent with classical pharmacological thought (Bockaert, et al., 2006). Even in cases of very high structural homology between receptor subtypes, the functional impact of stimulation may be notably oppositional (Bockaert, et al., 2006; Bubar and Cunningham, 2008) and the molecular characteristics of the protein complex may overlap, but are not identical (Becamel, et al., 2004). The significance of these distinct aspects of the 5-HT system is largely a mystery, primarily because of our overall lack of knowledge. However, the more we learn about the biomachinery of the 5-HT system, the more these processes will yield to a greater understanding and recognition of its importance in cocaine dependence as well as overall brain function.

5. Cocaine Reward and Serotonin

Food, water, sex or an abused drug can serve as a rewarding stimulus that positively reinforces, and increases the probability of, behavior leading to its consumption (Morse and Skinner, 1958). Multiple, somewhat distinguishable, facets of reward include hedonic value (`liking'), the organism's motivation to approach and consume rewards (incentive salience; `wanting'), and the learning of predictive associations between the reward and allied internal/external stimuli (drug-associated stimuli) (Berridge, et al., 2009). The activity of 5-HT neurons that innervate limbic-corticostriatal circuit controls the hedonic value of natural rewards (Nakamura, et al., 2008; Ranade and Mainen, 2009) and the motivational aspects of reward evoked by intracranial self-stimulation (Miliaressis, 1977; Simon, et al., 1976; Van der Kooy, et al., 1978). Electrophysiological studies in monkeys suggest that neurons in the DRN encode reward-seeking behaviors, and that DRN 5-HT neurons broadcast reward-related information to the forebrain (Bromberg-Martin, et al., 2010; Inaba, et al., 2013; Miyazaki, et al., 2011a; Miyazaki, et al., 2011b). Utilizing optogenetic technologies, the selective stimulation of mPFC neurons that project directly to the DRN resulted in a profound influence over a motivated behavior (Warden, et al., 2012) which is likely due to control of neuronal firing and 5-HT efflux in the DRN (Celada, et al., 2001). While these data strongly support the involvement of 5-HT innervation of forebrain in reward processing, there is little known about how 5-HT neurons coordinate the hedonic, motivational and learned aspects of cocaine reward. It is clear that cocaine binds to SERT, inhibits reuptake and increases extracellular 5-HT efflux (Koe, 1976), actions that have profound implications for the cellular activity of 5-HT raphe neurons (Cunningham and Lakoski, 1988; Cunningham and Lakoski, 1990; Pitts and Marwah, 1986) and 5-HT efflux and neuronal signaling in the terminal regions of raphe 5-HT neurons, including cortical and striatal regions (Bradberry, et al., 1993; Cameron, et al., 1997; Parsons and Justice, Jr., 1993; Pum, et al., 2007). Thus, cocaine exposure significantly alters the function of 5-HT neurons and 5-HT signaling in downstream targets in limbic-corticostriatal circuitry, and, as such, would likely impact the control of 5-HT neurons over reward processing.

The hedonic aspects of cocaine reward as well as the incentive motivational value attributed to cocaine reward and cocaine-associated cues are studied in the self-administration assay under controlled conditions in animals. Elegant self-administration assays have also been developed in humans (Comer, et al., 2008; Matuskey, et al., 2012), and applied to study cocaine reward (Fischman and Foltin, 1992; Fischman and Schuster, 1982), although reports in humans predominantly rely on self-report questionnaires to explore the euphorigenic and subjective effects of cocaine. In drug self-administration, the presentation of an abused drug as an appetitive “reward” contingent upon a behavioral response increases the probability that that behavior will reoccur. There are multiple self-administration paradigms which are employed to study drug reward processing in animals. Evaluation of active drug self-administration under experimental manipulations allows deductions about the role of a specific signaling pathway in the rewarding (reinforcing) effects of the self-administered drug. The progressive ratio self-administration variant in which the number of responses required for each reinforcer increases progressively during the session taps into the motivation to approach and consume rewards (incentive salience); the breakpoint is used as a measure of the motivation to take cocaine (Roberts, et al., 2007). The predictive associations between cocaine reward and allied internal/external stimuli are frequently assessed by measuring the learned behavioral output (“drug-seeking”) within the drug-taking context and/or in the presence of discrete drug-associated cues during forced abstinence or following repeated extinction training (Marchant, et al., 2013; Pickens, et al., 2011). There is a great deal of intriguing information emerging concerning the control of cues that are discrete (e.g., light or tone delivered with the drug) (Cunningham, et al., 2012; Meil and See, 1996; Nic Dhonnchadha, et al., 2009), contextual (environment is which drug self-administration occurs) (Crombag, et al., 2008; Hearing, et al., 2011), discriminative (predictive of drug availability) (Bradberry and Rubino, 2004; Kallupi, et al., 2013; Weiss, et al., 2000) or provoked by external stimuli such exposure to the drug itself (de Wit and Stewart, 1981) or stressful circumstances (Ahmed and Koob, 1997; Goeders and Guerin, 1994). The propensity for cocaine-associated cues to trigger relapse-like behavior in animals (return to attempts to deliver cocaine) (Kalivas and McFarland, 2003) as well as craving and relapse in humans and to activate extended limbic-corticostriatal circuitry (Childress, et al., 1999; Kosten, et al., 2006; Sinha and Li, 2007), elevate the need to understand the mechanisms through which cocaine and cocaine-associated cues so powerfully control behavior. The dominant hypothesis in the field is that the neural circuitry generating the reinforcing effects of abused drugs converge with those that serve as the substrate for engendering drug-taking (Kalivas and McFarland, 2003). Animal models provide the opportunity to address hypotheses employing selective ligands and manipulations of the 5-HT system, many of which are not available for human research. Although several additional models are employed (e.g., conditioned place preference, conditioned hyperactivity, etc.), here we focus predominantly upon the results derived from self-administration paradigms.

Cocaine is a robust reinforcer in self-administration assays in animals and humans, and its hedonic value is under the control of 5-HT as assessed by studies of rate of responding for cocaine and/or breakpoints. A summary of studies across rodents and monkeys is shown in Table 1 (Cocaine Reward; please note that Table 1 collapses observations across multiple types of paradigms and the reader is directed to the actual publications to gain a complete appreciation of the methodologies employed and the resulting observations). The potency of cocaine analogues to support self-administration correlated negatively with potency to bind to SERT (Ritz, et al., 1987), an observation which suggests that 5-HT may contribute an inhibitory role in cocaine reward. Notably, increased breakpoints for cocaine seen following depletion of central 5-HT after intracerebroventricular (ICV) infusion of the neurotoxin 5,7-dihydroxytryptamine (5,7-DHT) correlated with decreases in 5-HT in midbrain, but not NAc or amygdala (Roberts, et al., 1994). Localized depletion of 5-HT in the medial forebrain bundle or amygdala resulted in increased breakpoints (Loh and Roberts, 1990) suggesting that forebrain 5-HT innervation is critical to cocaine reward. Systemic administration of l-tryptophan to increase central 5-HT via synthesis (Carroll, et al., 1990b; McGregor, et al., 1993), the 5-HT releaser fenfluramine (Glowa, et al., 1997) or the selective 5-HT reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) fluoxetine (Carroll, et al., 1990a; Oleson, et al., 2011; Peltier and Schenk, 1993; Richardson and Roberts, 1991) suppressed the reinforcing and motivational properties of cocaine. In sum, increased and decreased central 5-HT tracked with blunted and augmented reinforcing properties of cocaine, respectively. There are no published reports of which we are aware that have evaluated the influence of 5-HT manipulations on cocaine self-administration in humans directly. However, in self-report analyses, fluoxetine suppressed cocaine-induced subjective effects and drug “liking” (Walsh, et al., 1994) while tryptophan depletion augmented cocaine-induced drug “wanting” (Cox, et al., 2011) but suppressed the “high” induced by intravenous cocaine (Aronson, et al., 1995). These few results in humans must be interpreted with caution as it is unclear whether self-report of drug-induced state reflects sensitivity to the reinforcing effects of the drug (Matuskey, et al., 2012), however they provide support to the general concept that 5-HT may regulate the reward value of cocaine.

Further clarity in understanding this question is provided by analyses of cocaine reward following pretreatment with a selective 5-HT receptor ligand, however, no such compounds are yet available for analyses in humans (see 9. Implications for Treatment of Cocaine Addiction). Table 1 summarizes animal studies with available compounds with the best selectivity for a given 5-HT receptor. These data suggest that the 5-HT1AR (Czoty, et al., 2002; Muller, et al., 2007; Nader and Barrett, 1990; Peltier and Schenk, 1993) and 5-HT2CR (Cunningham, et al., 2011; Fletcher, et al., 2002; Grottick, et al., 2000; Neisewander and Acosta, 2007) provide inhibitory tone over cocaine reward while an excitatory role for the 5-HT1BR (Parsons, et al., 1998; Pentkowski, et al., 2009; Pentkowski, et al., 2012; Przegalinski, et al., 2007; Przegalinski, et al., 2008) is supported; the 5-HT2AR appears to uninvolved in the reinforcing or motivational effects of cocaine (Filip, 2005; Fletcher, et al., 2002; Nic Dhonnchadha, et al., 2009), and there are conflicting data as to the involvement of the 5-HT6R (Valentini, et al., 2013; van Gaalen, et al., 2010) while the 5-HT2BR, 5-HT4R and 5-HT5R remain to be evaluated. These data support a role for 5-HT in the control of reward processing for cocaine and one which is dependent upon involvement of specific receptor subtypes.

Serotonin innervation (Kosofsky and Molliver, 1987; Lidov, et al., 1980; Vertes and Linley, 2008) and distribution of SERT (Maloteaux, 1986; Pickel and Chan, 1999) are not uniform across forebrain and the magnitude and temporal attributes of the effects of cocaine on 5-HT efflux is region-specific (Bradberry, et al., 1993; Cameron, et al., 1997; Parsons and Justice, Jr., 1993; Pum, et al., 2007). Systemic cocaine administration elevates 5-HT efflux in mesocorticostriatal regions, including the VTA (Chen and Reith, 1994; Parsons and Justice, Jr., 1993), NAc (Andrews and Lucki, 2001; Parsons and Justice, Jr., 1993) as well as PFC and other neocortical areas (Mangiavacchi, et al., 2001; Pum, et al., 2007). Localized microinjections of 5-HT2R ligands significantly alter cocaine-evoked behaviors (i.e., hyperactivity, discriminative stimulus effects) (Bubar and Cunningham, 2008), however, only a handful of published studies have manipulated 5-HT receptors in discrete brain nuclei and assessed the reinforcing or motivational effects of cocaine in self-administration paradigms. These few studies focused on the VTA (5-HT2CR) (Fletcher, et al., 2004), the NAc (5-HT1BR) (Pentkowski, et al., 2012) or mPFC (5-HT2AR, 5-HT2CR) (Anastasio, et al., 2014; Pentkowski, et al., 2010; Pockros, et al., 2011). Intra-VTA activation of 5-HT2CR attenuated cocaine intake on both fixed and progressive ratio schedules (Fletcher, et al., 2004), matching directionally the results following systemic administration of a selective 5-HT2CR agonist (Cunningham, et al., 2011; Fletcher, et al., 2002; Grottick, et al., 2000; Neisewander and Acosta, 2007). Overexpression of the 5-HT1BR in the medial NAc shell resulted in a leftward/upward shift in the dose-effect curve and increased breakpoint for cocaine delivery (Pentkowski, et al., 2012), consistent with observations seen after systemic 5-HT1BR agonists (Parsons, et al., 1998). Microinfusion of a selective 5-HT2AR antagonist into ventral mPFC (Pockros, et al., 2011) or a 5-HT2CR agonist into the prelimbic, infralimbic mPFC or the neighboring cingulate cortex were ineffective at altering cocaine intake (Pentkowski, et al., 2010). Thus, based upon this limited data set, the NAc 5-HT1BR and VTA 5-HT2CR exert an excitatory and inhibitory role, respectively, to control the reinforcing and motivational properties of cocaine.

6. Impulsivity and Serotonin

Impulsivity is not a unitary construct, but can be considered a “trait” comprised of several components that contribute to its characteristic pattern of poorly conceived, disadvantageous decisions and behaviors (Evenden, 1999a; Moeller, et al., 2001a). Some of the components of impulsivity as a cognitive construct include maladaptive inhibitory control, failure to consider the consequences of behaviors, and a preference for immediate rather than delayed rewards (Evenden, 1999a; Moeller, et al., 2001a). Impulsive behavior is not always aberrant as there are ecological advantages for the decision to act versus to reflect. In the United States, the lifetime prevalence of self-reported impulsive behavior is ~17% and within this population ~83% report a lifetime history of at least one major psychiatric disorder including addiction (Chamorro, et al., 2012). As impulsivity is a multi-dimensional construct, at present, the rank order and importance of each dimension within any one psychiatric disorder is unclear. Impulsivity is highly associated with “externalizing” psychiatric disorders such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, bipolar disorder and drug dependence (Chamorro, et al., 2012). It is likely that impulsive behavior contributes significantly to several components of the addiction cycle, including initial choice to use drugs, the establishment of repetitive patterns of drug intake, the transition from casual to compulsive use to dependence and cue-evoked relapse events as proposed by the results of animal studies (Anastasio, et al., 2014; Belin, et al., 2008; de Wit and Richards, 2004). Thus, the convergence of the impulsivity trait with the dynamic state of cocaine dependence may contribute to greater vulnerability to relapse.

The multidimensional nature of impulsivity is reflected in the numerous measurement tools developed for laboratory assessments of impulsivity in humans and animals (Winstanley, 2011). These models are highly translational in that the operant tasks are employed across species (human, primate, and rodent) with appropriate alterations in design. Although no current preclinical model successfully measures all facets of impulsivity within individual subjects, animal models enrich and foster investigations into the neuromolecular underpinnings of disorders characterized by aberrant impulsivity enabling conclusions to be drawn across preclinical and clinical studies. Generally divided into three categories (Table 2), each task is designed to measure a different dimension of impulsivity: (1) measures of decision-making, in which impulsivity is defined as preference for a smaller-sooner reward over a larger-later reward; (2) behavioral disinhibition, in which impulsivity is assessed as premature or disinhibited responses; and (3) punishment/extinction, in which impulsivity is defined as the perseveration of a response which is punished or not reinforced (Table 2) (for reviews) (Cardinal, et al., 2004; Robbins, 2002; Winstanley, 2011). [We present animal models as measures of “impulsive action” or “impulsive choice” to avoid using anthropomorphic labels for animal behaviors.]

Table 2.

Comparison of behavioral laboratory measures of impulsivity

| Rats | Humans |

|---|---|

| Impulsive Choice Tasks | Reward-Directed Paradigms |

| Delay Discounting | Delay Discounting (Delayed Reward) |

| Iowa Gambling Task | |

| Impulsive Action Tasks | Rapid-Decision Paradigms |

| Stop Signal Task | Stop Signal Reaction Time Task |

| Go-NoGoTask | Go-NoGoTask |

| One/Five-Choice Serial Reaction Time Task | Continuous Performance Task; Immediate and Delayed Memory Task |

| Differential Reinforcement of Low-Rate | Single Key Impulsivity Paradigm |

| Fixed Consecutive Number Task | |

| Punishment/Extinction Tasks | Punishment/Extinction Paradigms |

| Fixed-Interval Extinction | lntra-/Extra-dimensional Set Shifting |

| Maze-based Set Shifting |

Impulsive action (behavioral disinhibition; rapid-response impulsivity; difficulty in withholding a prepotent response) and impulsive choice (decision-making; delayed reward measures) are two primary dimensions of impulsivity that have been associated with cocaine dependence in humans (Moeller, et al., 2001a; Moeller, et al., 2001b; Patkar, et al., 2004) and in rodent models of cocaine addiction (Anastasio, et al., 2014; Belin, et al., 2008; Perry, et al., 2005). The results of these studies suggest that inherent levels of impulsive behavior are positively correlated with the sensitivity to the effects of psychostimulants. Further, acute or chronic exposure to psychostimulants changes the probability of impulsive behaviors. In general, cocaine has been noted to increase impulsive action (Anastasio, et al., 2011; Paine and Olmstead, 2004; Stoffel and Cunningham, 2008) and impulsive choice (Logue, et al., 1992; Paine, et al., 2003), although there is not an absolute consensus with regard to the outcome of investigator-delivered cocaine administration across tasks (Paine, et al., 2003). Studies in healthy controls indicate a relationship between individual differences in response inhibition and activated neural circuits (Congdon, et al., 2010), however, the specific neural substrates that underlie these individual differences remain relatively unexplored.

Behavioral characteristics common to impulsivity have been linked to various aspects of serotonergic function within the corticostriatal circuit. There is extensive evidence that 5-HT manipulations alter performance in impulsivity tasks in humans and in animals (Table 1) (for reviews) (Dalley and Roiser, 2012; Fineberg, et al., 2010; Pattij and Vanderschuren, 2008; Winstanley, et al., 2006). Maladaptive impulsive behaviors have been correlated with diminished 5-HT levels in plasma and 5-HT metabolite (5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid) levels in cerebrospinal fluid (Brown and Linnoila, 1990; Stein, et al., 1993; Virkkunen and Narvanen, 1987), suggesting that an imbalance in 5-HT function may underlie impulsive behaviors. Depletion of 5-HT globally by 5,7-DHT (Winstanley, et al., 2004a) or PCPA (Evenden, 1998a; Masaki, et al., 2006) as well as 5,7-DHT into the DRN increased impulsive action (Harrison, et al., 1997). In healthy volunteers, tryptophan depletion has been reported to increase impulsivity in laboratory tasks (Booij, et al., 2006; Dougherty, et al., 2007; LeMarquand, et al., 1999; Walderhaug, et al., 2002; Walderhaug, et al., 2007), as does tryptophan challenge, but only in those subjects with high trait impulsivity (Markus and Jonkman, 2007; Young, et al., 1988). The 5-HT releaser fenfluramine and the SSRI fluoxetine suppressed impulsive action in rodents (Baarendse and Vanderschuren, 2012; Humpston, et al., 2013; Wolff and Leander, 2002), observations mirrored in humans (Manuck, et al., 1998; Moeller, et al., 2007; Patkar, et al., 2004; Soloff, et al., 2003). While the hypothesis is that decrements in 5-HT function may underlie impulsive behaviors, its validity has been challenged by recent findings that ablation of 5-HT terminals in the frontal cortex or the NAc did not alter impulsive actions in rats (Fletcher, et al., 2009) and that high levels of impulsive action are associated with elevated 5-HT release in the mPFC (Dalley, et al., 2002; Puumala and Sirviö, 1998). The inconsistent effects of global 5-HT manipulations are best explained by differences between tasks employed across studies and underscores not only the multidimensionality of impulsivity, but also that different tasks tap into distinct aspects of impulsive behavior that are engendered through discrete brain circuits and neural substrates. Furthermore, the complexity of impulsivity is highlighted by findings that the 5-HT system selectively regulates “action restraint” measures of impulsive action, but not “action cancellation” measures or impulsive choice (Winstanley, et al., 2004b). These last observations suggest that 5-HT plays a nuanced role in impulsivity, perhaps driven at the level of the 5-HT-receptive proteins and interactions with the limbic-corticostriatal DA and glutamate systems (Dalley and Roiser, 2012; Winstanley, et al., 2006).

Preclinical laboratories have pioneered elucidation of the pivotal roles for specific 5-HTXR in impulsive behaviors using the most selective pharmacologic tools; Table 1 summarizes studies with selective 5-HT receptor ligands upon systemic administration and virally-mediated gene transfer methods to manipulate expression of specific receptor proteins in subregions of the limbic-corticostriatal circuit in adult rats. Mixed results with 5-HT1AR ligands (Blokland, et al., 2005; Carli and Samanin, 2000; Evenden, 1998b; Evenden, 1999b) and incomplete pharmacological and/or genetic assessments of the 5-HT1BR complicates identification of a role for the 5-HT1R family in the emergence of impulsive action while the 5-HT6R does not appear to play a primary role in impulsive action (de Bruin, et al., 2013; Talpos, et al., 2006). A selective 5-HT2AR antagonist (e.g., M100907) (Anastasio, et al., 2011; Fletcher, et al., 2007; Fletcher, et al., 2011; Winstanley, et al., 2004b) or a selective 5-HT2CR agonist (e.g., Ro 60-0175, WAY163909) (Cunningham, et al., 2012; Fletcher, et al., 2007; Fletcher, et al., 2011; Navarra, et al., 2008; Winstanley, et al., 2004b) consistently reduced impulsive action. Systemic administration of the preferential 5-HT2AR agonist 2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodoamphetamine (DOI) increased impulsivity (Blokland, et al., 2005; Carli and Samanin, 2000; Evenden, 1998b; Evenden, 1999b; Evenden and Ryan, 1999; Hadamitzky and Koch, 2009; Koskinen, et al., 2000a; Koskinen, et al., 2000b; Koskinen, et al., 2003) and the 5-HT2CR antagonist SB242084 produced qualitatively similar results to DOI (Anastasio, et al., 2013; Winstanley, et al., 2004b; Young, et al., 2011). Thus, there is an almost-perfect oppositional control of impulsive action observed in preclinical studies upon systemic administration of 5-HT2R ligands. Lastly, the possibility that the 5-HT2AR and 5-HT2CR may act in concert to control impulsivity is suggested by the discovery that impulsive action was synergistically suppressed by very low, ineffective doses of a selective 5-HT2AR antagonist (M100907) plus a selective 5-HT2CR agonist (WAY163909) (Cunningham, et al., 2012).

7. Cocaine Cue Reactivity and Serotonin

Drug-associated cues have long been hypothesized to be an essential driver in the cycle of addiction, relapse and recovery (Wikler, 1948), and psychological theorists have greatly enriched our understanding of the intertwined natures of drug reward and drug-related stimuli at behavioral and neuromolecular levels (Crombag, et al., 2008; Kelley, 2004; Richard, et al., 2013; Saunders and Robinson, 2013). Physiological responses (Robbins, et al., 1997), and altered brain activation patterns in limbic-corticostriatal circuits are observed upon exposure to cocaine-associated cues in cocaine-dependent subjects (Carpenter, et al., 2006; Goldstein, et al., 2007; Hester and Garavan, 2009; Potenza, et al., 2012). Attentional bias toward cocaine-associated cues measured in the cocaine-word Stroop task correlates positively with the severity of cocaine craving (Copersino, et al., 2004; Field, et al., 2009) and is also predictive of treatment outcomes in cocaine-dependent subjects (Carpenter, et al., 2006). Given their importance in addictive disorders, individual differences in sensitivity to reward-associated cues are now under study as a factor predictive of the propensity for drug use and/or relapse events in humans (Mahler and de Wit, 2010) and animals (Flagel, et al., 2010; Liu, et al., 2013; Saunders and Robinson, 2013; Tomie, et al., 2008; Yager and Robinson, 2013).

The phrase “cue reactivity” is a descriptor employed here to designate the sensitivity to drug-associated stimuli conditioned to the drug-taking experience regardless of the clinical scale or procedure employed to analyze this behavioral construct in humans or animals. However, there is not a consensus as to the operational definition of cue reactivity in experimental studies nor as to the protocols that provide the most translational applicability to the human situation. Of relevance to the present analysis of 5-HT control over drug-seeking, the experimental design of most pharmacological and genetic manipulations includes acquisition and maintenance of a short or long-access cocaine self-administration followed by extinction and subsequent reinstatement sessions in the presence of the drug-associated environment (Cunningham, et al., 2012; Fletcher, et al., 2007; Nic Dhonnchadha, et al., 2009; See, 2005; Shaham, et al., 2003). An alternative is to employ a self-administration assay followed by assessment of cocaine-seeking during an imposed withdrawal period (forced abstinence) (Anastasio, et al., 2014; Fuchs, et al., 1998; Grimm, et al., 2001; Liu, et al., 2013; Panlilio and Goldberg, 2007). The operant responses (e.g., lever presses) during the reinstatement session are recorded, but may or may not result in the delivery of cocaine-associated cues. Each variable of the protocol employed is ultimately important in dissecting the neurobiology of drug-seeking, however, the neuroadaptations that underlie withdrawal-related sequela determined following extinction training versus during forced abstinence are not identical (Di Ciano and Everitt, 2002; Schmidt, et al., 2001; Self, et al., 2004; Sutton, et al., 2003). Because of the limited number of studies that have evaluated the effects of selective 5-HT manipulations across impulsive action, cocaine reward and cocaine-seeking (Table 1), we have summarized results of studies in which cocaine-seeking was assessed during forced abstinence or following extinction training and under conditions in which the cocaine-seeking response was/was not reinforced by discrete drug-associated cues.

Depletion of forebrain 5-HT (Tran-Nguyen, et al., 1999; Tran-Nguyen, et al., 2001) and drugs which promote increased central 5-HT (fenfluramine, fluoxetine) (Baker, et al., 2001; Burmeister, et al., 2003; Burmeister, et al., 2004)) suppressed cue-evoked drug-seeking(Table 1). Cocaine-primed drug-seeking was, in contrast, elevated under conditions of 5-HT depletion (Tran-Nguyen, et al., 1999) and unaffected by fenfluramine and fluoxetine (Burmeister, et al., 2003). The outcomes suggest that 5-HT plays differential roles over cocaine-seeking versus cocaine reward (above), and between drug-seeking generated in the absence or presence of cocaine itself (Table 1). This pattern of observations is mirrored in humans as tryptophan depletion suppressed cue-evoked craving in the absence of cocaine administration (Satel, et al., 1995) and augmented cocaine-primed craving (Cox, et al., 2011) suggesting that cue- and cocaine-primed craving are under the regulation of 5-HT neurotransmission. A defining characteristic of these studies is whether cocaine is present at time of study, however, it is necessary to consider the small number of studies and that the neuroadaptations associated with repeated cocaine exposure are superimposed upon the overlapping, widespread changes of central 5-HT levels evinced by these 5-HT manipulations (see 8. Intersection of Impulsivity and Cue Reactivity in Cocaine Dependence).

The employment of pharmacological and genetic tools in animals allows insight into the controlling features of 5-HT neurotransmission over cocaine-seeking. A perusal of Table 1 indicates that, while mixed results obfuscate the role of 5-HT1AR (Czoty, et al., 2002; Muller, et al., 2007; Nader and Barrett, 1990; Peltier and Schenk, 1993), blockade of the 5-HT6R suppresses both cue- and cocaine-primed cocaine-seeking (Valentini, et al., 2013; van Gaalen, et al., 2010). The 5-HT2BR, 5-HT4R and 5-HT5R remain to be evaluated, but there is strong support for a regulatory role of the 5-HT1BR, 5-HT2AR and 5-HT2CR in cocaine cocaine-seeking. With regard to the 5-HT1BR, Neisewander and colleagues have shown that a selective 5-HT1BR agonist suppresses cue- and cocaine-primed drug-seeking (Acosta, et al., 2005; Pentkowski, et al., 2009), although conflicting data are reported (for a discussion, see (Przegalinski, et al., 2008). As predicted by the suppressive effects of a systemically-administered 5-HT1BR agonist (Acosta, et al., 2005; Pentkowski, et al., 2009), overexpression of the 5-HT1BR in the NAc (Pentkowski, et al., 2012) reduced both cue- and cocaine-evoked drug-seeking. Interestingly, a diametrically-opposite role for the 5-HT1BR is seen for cocaine intake (Parsons, et al., 1998; Pentkowski, et al., 2009; Pentkowski, et al., 2012; Przegalinski, et al., 2007). These data highlight that a given 5-HT receptor can play a differential role in cocaine reward versus responsivity to cocaine-conditioned stimuli; in the case of the 5-HT1BR, the differential role likely reflects the status of the 5-HT1BR expression and function which is persistently altered during withdrawal from cocaine self-administration (O'Dell, et al., 2006). This series of studies highlights the need to understand the dynamic neuroadaptation of 5-HT systems consequent to repeated cocaine self-administration to best comprehend the mechanisms underlying cue reactivity.

The most consistent evidence of a role for 5-HT receptors in cocaine cue reactivity has emerged from evaluation of 5-HT2AR and 5-HT2CR manipulations. In all studies conducted to date, a selective 5-HT2AR antagonist (M100907) (Fletcher, et al., 2002; Nic Dhonnchadha, et al., 2009) or a selective 5-HT2CR agonist (Ro 60-0175, WAY163909) share efficacy to suppress cue- and cocaine-primed drug-seeking (Cunningham, et al., 2011; Fletcher, et al., 2002; Grottick, et al., 2000; Neisewander and Acosta, 2007). The selective 5-HT2CR antagonist SB242084 increased cocaine-seeking in most studies (Burbassi and Cervo, 2008; Burmeister, et al., 2004; Fletcher, et al., 2002; Manvich, et al., 2012; Neisewander and Acosta, 2007; Pelloux, et al., 2012) and actually exhibited stimulant-like properties and supported self-administration in non-human primates (Manvich, et al., 2012). The possibility that the 5-HT2AR and 5-HT2CR may act in concert is suggested by the fact that both cue- and cocaine-primed drug-seeking were synergistically suppressed by very low, ineffective doses of a selective 5-HT2AR antagonist (M100907) plus a selective 5-HT2CR agonist (WAY163909) (Cunningham, et al., 2012). Because the 5-HT2AR and 5-HT2CR are oppositional in vivo (Bubar and Cunningham, 2008), results observed following administration of nonselective 5-HT2A/2CR antagonists are confounded by a concurrent blockade of the 5-HT2CR which would be expected to have oppositional actions to those of blockade of the 5-HT2AR, therefore, it is perhaps not surprising that non-selective 5-HT2A/2CR antagonists failed to attenuate cocaine-seeking in animals (Burmeister, et al., 2004; Filip, 2005; Schenk, 2000) or humans (Ehrman, et al., 1996) or influence self-reported euphoric effects of cocaine (Newton, et al., 2001) or craving (De La Garza, et al., 2005; Loebl, et al., 2008). Thus, once distinguished pharmacologically, the 5-HT2AR and 5-HT2CR plays an excitatory and inhibitory role, respectively, in cue reactivity.

8. Intersection of Impulsivity and Cue Reactivity in Cocaine Dependence

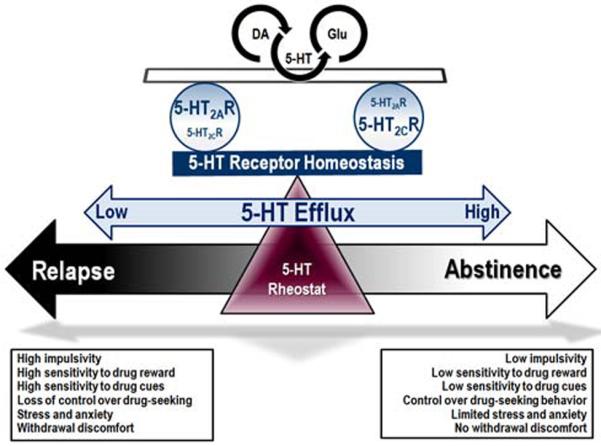

High impulsivity and cue reactivity are linked to an increased propensity to relapse (Moeller, et al., 2001b; O'Brien, et al., 1998) while studies suggest that these are interlocked phenotypes in humans (Liu, et al., 2011) and animals (Anastasio, et al., 2014; Belin, et al., 2008; Perry, et al., 2005). Serotonin is a sensitive homeostatic regulator of these interlocked phenotypes as measured following 5-HT manipulations which disrupt the 5-HT balance in the entire brain (e.g., 5,7-DHT, fluoxetine; Table 1). Serotonin neurons cast a wide net to all corners of the brain and their influence is “implicated in virtually everything, but responsible for nothing” (Jacobs and Fornal, 1995). Thus, 5-HT acts not so much as a sole mediator of specific behaviors, but rather as an elemental rheostat of “higher-order” neural circuits. Serotonin functions to constrain the response to arousing, rewarding and motivating stimuli while reduced 5-HT potentiates the impact of such stimuli (Izquierdo, et al., 2012; Lucki, 1998; Soubrié, 1986) and disengages stimuli from their emotional significance (Beevers, et al., 2009; Deakin, 1998). Within this construct, 5-HT flexibly modulates the organism's “drive to withdraw” from aversive or intense stimulation relative to the “withdrawn” state of low reactivity to stimulation (Tops, et al., 2009). When a global deficiency of 5-HT (e.g., 5,7-DHT) predicts the loss of restraint over arousing stimuli, measures of impulsive action, cocaine reward and cocaine-primed cocaine-seeking were elevated; under conditions of tonic elevation of 5-HT efflux (e.g., fluoxetine), impulsive action, cocaine reward and cue-evoked cocaine-seeking were diminished (Table 1). Such data give overall credence to the important role of 5-HT to control fundamental facets of the stimulus-response relationships that drive these behaviors. Increased firing of 5-HT neurons has been associated with “waiting” when the possibility of future reward is high (Miyazaki, et al., 2011a; Miyazaki, et al., 2011b; Miyazaki, et al., 2012b), a mechanism suggested to underlie serotonergic control over impulsive behavior (Miyazaki, et al., 2012a) and 5-HT can influence cognitive processing through both tonic and phasic mechanisms (Ranade and Mainen, 2009). The role of specific 5-HT receptor populations (e.g., 5-HT2AR and 5-HT2CR) as a nexus connecting these two phenotypes and the drive to relapse versus to maintain abstinence may be dependent upon tonic and phasic mechanisms which dictate serotonergic modulation over the limbic-corticostriatal circuit (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Serotonin serves as a key nexus for vulnerability to relapse.

The 5-HT neurotransmitter system regulates higher order neural circuits that ultimately control expression of the impulsivity and cue reactivity phenotypes that contribute to relapse to drug-seeking. Alterations in the level of 5-HT efflux and associated disruptions in 5-HT receptor homeostasis shifts the balance of 5-HT:DA:glutamate neurotransmission that govern impulsivity, sensitivity to reward and cues, and control over drug seeking. A global deficiency of 5-HT, such as that observed during withdrawal from cocaine administration, is associated with loss of restraint over arousing stimuli, such that measures of impulsive action, cocaine reward and cocaine-primed cocaine-seeking are elevated. These factors, coupled with elevated stress, anxiety and withdrawal discomfort set the stage for enhanced vulnerability to relapse. As such, medications that act to restore 5-HT rheostatic control may be effective in promoting abstinence. This may best be accomplished by targeting specific 5-HT receptors of which the 5-HT2AR and 5-HT2CR, which consistently exert oppositional influence upon impulsivity and cue reactivity, have emerged as key targets mediating the intersection of these interlocked phenotypes.

It is quite possible that impulsivity and related irregularities of the 5-HT system set the stage for neurochemical and behavioral vulnerability to cocaine-associated stimuli (Anastasio, et al., 2014). The mPFC has received the most attention as a site at which the 5-HT2AR and 5-HT2CR evoke oppositional control over behavior based upon the results of intracranial microinfusion studies. Localized infusion of a 5-HT2AR-selective antagonist into the ventral mPFC suppressed impulsive action (Winstanley, et al., 2003) and cue-evoked cocaine-seeking (Pockros, et al., 2011). Microinfusion of a 5-HT2CR agonist into the prelimbic or infralimbic mPFC, but not the neighboring anterior cingulate cortex, suppressed both cue- and cocaine-primed cocaine-seeking (Pentkowski, et al., 2010). Most recently, we found that virally-mediated 5-HT2CR knockdown in the mPFC resulted in both elevated impulsive action and cocaine-seeking relative to controls (Anastasio, et al., 2014). Thus, 5-HT control of impulsivity and cocaine cue reactivity (but not cocaine reward) intersects within the mPFC with oppositional roles for mPFC 5-HT2AR and 5-HT2CR.

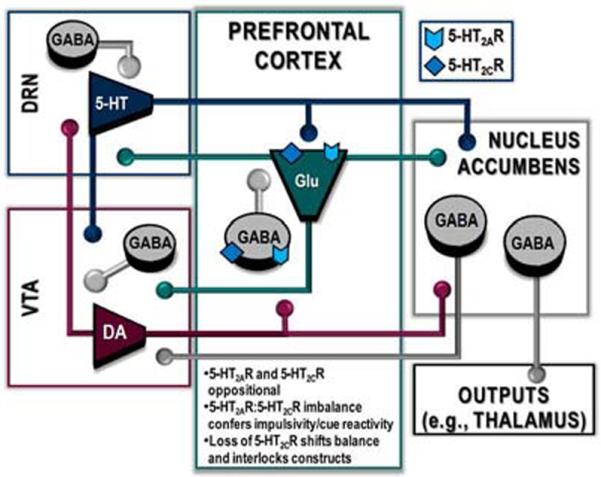

A 5-HT2AR:5-HT2CR balance within the mPFC may serve as a neurobiological rheostat over the mechanisms underlying impulsivity and sensitivity to cues through a highly organized interaction between 5-HT, DA, and glutamate systems within the limbic-corticostriatal circuit (Figure 2). Serotonin neurotransmission through its cognate 5-HT2AR and 5-HT2CR is important in establishing the excitatory/inhibitory balance in the mPFC microciruitry, although the specific regulatory forces involved are decidedly understudied. Rich 5-HT innervation to the mPFC arises from 5-HT neurons of the DRN and MRN and the mRNA and/or protein for the 5-HT2AR and 5-HT2CR are found in both primary neuronal types in the mPFC (Burnet, et al., 1995; Pompeiano, et al., 1994). A quantitative analysis indicated that 50–66% of pyramidal neurons express 5-HT2AR mRNA; within layers II–V, nearly every glutamate neuron expressed 5-HT2AR mRNA (de Almeida J. and Mengod, 2007). The great majority of 5-HT2AR labeling in mPFC is postsynaptic, although some localization in presynaptic terminals has been reported (Miner, et al., 2003). A more modest expression of 5-HT2AR mRNA is found in GABA interneurons (~13–46%), most notably parvalbumin- and calbindin-positive cells (de Almeida J. and Mengod, 2007). By comparison, lower overall expression of 5-HT2CR mRNA (Pompeiano, et al., 1994) and protein are observed relative to 5-HT2AR in the mPFC (de Almeida J. and Mengod, 2007); we have reported prominent expression of 5-HT2CR immunoreactivity in parvalbumin-positive interneurons in the mPFC (Liu, et al., 2007) consistent with previous observations (Burnet, et al., 1995). Activation of either receptor can result in depolarization of pyramidal neurons or GABA interneurons which regulate pyramidal outflow (Alex and Pehek, 2006; Araneda and Andrade, 1991; Beique, et al., 2007; Puig, et al., 2010). Importantly, the net consequence of 5-HT2AR and 5-HT2CR function in mPFC appears to be interactive; there is evidence that constitutive knockout of the 5-HT2AR results in upregulation of 5-HT2CR control over the excitability of mPFC pyramidal neurons (Beique, et al., 2007). This interaction between the 5-HT2AR and 5-HT2CR in mPFC is supported by our observation that, consequent to knockdown of the 5-HT2CR in mPFC, 5-HT2AR control over impulsive action is augmented (Anastasio and Cunningham, unpublished). These data suggest that a functional disruption of the cortical 5-HT2AR:5-HT2CR balance may be a key neurobiological trigger that sets the stage for enhanced impulsivity and sensitivity to cues. There is now evidence that 5-HT receptor control of PFC in humans remains balanced across development into adulthood (Lambe, et al., 2011) and that dysregulation of individual receptor subtypes during development (such as consequent to maternal deprivation) (Benekareddy, et al., 2010) could have long-lasting repercussions for 5-HT receptor control of the mPFC microcircuitry. Such developmental disruptions in 5-HT control of mPFC communications could set up conditions conducive to generation of inherent vulnerability traits such as impulsivity (Lambe, et al., 2011) or generalized cue reactivity (de Wit and Richards, 2004) that could promote initial drug use, trigger addictive and/or relapse processes. The magnitude and nature of the cellular response to 5-HT, however, are heavily dependent upon the cortical subregion, cellular morphology and laminar position of the neurons (Beique, et al., 2007; Gonzalez-Burgos, et al., 2005; Liu, et al., 2007). Similarly, the 5-HT2AR and 5-HT2CR could control mPFC output through actions in the same or different, interacting neurons or neuronal networks (Araneda and Andrade, 1991; Puig, et al., 2010). Nonetheless, we propose that an imbalance in the mPFC 5-HT2AR:5-HT2CR interaction disrupts the cortical microcircuitry resulting in profound neuroplastic consequences to overlapping and interlooping subcortical structures and shifts the 5-HT:DA:glutamate homeostatic framework within the limbic-corticostriatal circuit.

Figure 2. The PFC 5-HT2AR and 5-HT2CR is an important site of action for the intersection of impulsivity and cue reactivity.

A schematic overview of the overlapping and reciprocal interactions between 5-HT, DA and glutamate neurotransmission is illustrated within the limbic-corticostriatal circuit. Serotonin neurons (blue) from the dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN) innervate the ventral tegmental area (VTA), nucleus accumbens (NAc) and prefrontal cortex (PFC); DA neurons (red) from the VTA project to the DRN, NAc and PFC; pyramidal glutamate neurons (green) from the PFC innervate the DRN, VTA and NAc; GABA medium spiny projection neurons (gray) from the NAc project to the VTA and other primary output systems (e.g., thalamus). The microcircuitry within each brain region is comprised of the respective 5-HT, DA, or glutamate projection neurons and GABA interneurons. Within the PFC 5-HT2AR (chevron) and 5-HT2CR (diamond) are each localized to GABA interneurons and pyramidal glutamate projection neurons, and thus, are perfectly situated to tightly control the PFC microcircuitry. We theorize that disruption of the oppositional 5-HT2AR:5-HT2CR balance within the PFC shifts the 5-HT, DA and/or glutamate homeostatic framework within the limbic-corticostriatal circuitry and sets the stage for enhanced impulsivity and sensitivity to cues in cocaine dependence.

Studies to date support the overarching hypothesis that connections between impulsivity, cocaine cue reactivity and a dysregulated 5-HT system exist. However, whether dysfunction in 5-HT neurotransmission which promote impulsivity and cue reactivity (Table 1), contribute to or result from, repeated cocaine self-administration is not known. An important consideration in understanding the mechanistic roles of 5-HT is the fact that repeated cocaine self-administration evokes significant neuroadaptations that are likely to be entangled with critical addictive processes. The neuroplastic changes in DA and glutamate subsystems associated with cocaine self-administration are well-characterized and integrated into dominant theories of addiction (Kalivas and Volkow, 2005; Koob and Volkow, 2010), but the features of serotonergic neuroplasticity have only marginally been evaluated in appropriate animal models. For example, termination of cocaine self-administration resulted in decreased basal levels of extracellular 5-HT in the NAc that persisted for 6–10 hours (Parsons, et al., 1995; Weiss, et al., 2001), although other timepoints and regions of the limbic-corticostriatal circuit have not been evaluated in this regard. Changes in the functional status of the 5-HT2R systems appear to follow repeated cocaine exposures as well, however, the use of widely variant doses and regimens of cocaine administration (predominantly, investigator-delivered), and 5-HT2R ligands which lack specificity are likely to contribute to the mixed directional changes. Serotonergic receptor function is reportedly altered in rodents during withdrawal from repeated cocaine exposure (Baumann and Rothman, 1996; Darmani, et al., 1992; Filip, et al., 2006; Levy, et al., 1994) and in abstinent human cocaine abusers (Ghitza, et al., 2007; Handelsman, et al., 1998; Lee and Meltzer, 1994; Patkar, et al., 2006). Response-independent chronic cocaine exposure regimens investigated to date did not indicate robust effects on either 5-HT2AR or 5-HT2CR mRNA or protein expression (Javaid, et al., 1993; Johnson, et al., 1993; Neisewander, et al., 1994), however, long-term cocaine self-administration was associated with increased 5-HT2AR availability in the frontal cortex of monkeys (Sawyer, et al., 2012). These findings suggest that the altered responsiveness of 5-HT2AR or 5-HT2CR seen following repeated cocaine administration may be related to direct alterations in receptor expression.

There is also evidence that changes in expression, cellular localization and/or function of downstream effectors that couple to 5-HT2AR or 5-HT2CR may account in part for cocaine-associated sequela. For example, 5-HT2AR supersensitivity of some behavioral and neuroendocrine effects seen during withdrawal from repeated, investigator-delivered cocaine administration was associated with an increase in membrane-associated Gαq/11 protein expression in the hypothalamus and amygdala, rather than a specific increase in 5-HT2AR expression (Carrasco, et al., 2003; Carrasco, et al., 2004). Of note, the postsynaptic scaffolding protein PSD95 plays a key role in the surface expression and agonist-mediated internalization of 5-HT2AR (Abbas, et al., 2009; Xia, et al., 2003) and promotes desensitization of the 5-HT2CR (Abbas, et al., 2009; Gavarini, et al., 2006). Thus, despite the fact that the 5-HT2AR and 5-HT2CR share a great degree of homology (Bockaert, et al., 2006; Hoyer, et al., 2002), the regulation of these receptors are differentially and profoundly regulated by PSD95 (Abbas, et al., 2009; Becamel, et al., 2004; Xia, et al., 2003). Decreased expression of PSD95 was observed in mice treated chronically with cocaine, while mice with a targeted deletion of PSD95 exhibited enhanced cocaine-induced locomotor hyperactivity (Yao, et al., 2004). It is probable that the 5-HT2R:PSD95 interaction is essential to normal 5-HT neurobiology and that cocaine-induced neuroplasticity may engage such processes, however, few studies have critically evaluated the status of 5-HT2AR or 5-HT2CR function during phases of cocaine self-administration nor linked 5-HT neuroadaptations with impulsive action or cocaine-seeking. We have recently discovered that rats with the highest level of impulsive action or cocaine cue reactivity displayed the lowest levels of mPFC 5-HT2CR protein in mPFC, and were the least responsive to 5-HT2CR ligands (Anastasio, et al., 2014). Further, we found that synaptosomal PSD95 protein in the mPFC associated with the 5-HT2CR to a greater extent in high impulsive rats versus low impulsive rats (Anastasio, et al., 2014). This augmented 5-HT2CR:PSD95 association would be expected to desensitize and internalize the 5-HT2CR (Anastasio, et al., 2014). Given the potential interactive nature of 5-HT2AR and 5-HT2CR function in the mPFC (Anastasio and Cunningham, unpublished) (Beique, et al., 2007), we propose that dysregulation of cortical 5-HT2AR and 5-HT2CR may be a neurobiological mechanism underlying the intersection of impulsive action and cocaine cue reactivity.

9. Implications for Treatment of Cocaine Addiction

Relapse is a major challenge to achievement of successful remission of cocaine addiction, and predictors of relapse and treatment success would be helpful to control addictive behaviors. Progress in understanding the neurobiology of vulnerability factors for relapse and identifying predictors of individual vulnerability are important steps in increasing opportunities for prevention of cocaine addiction. For example, the use of screening to identify maladaptive impulsivity could be helpful to identify individuals at risk for drug use (Perry, et al., 2011). Identification and validation of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that predict impulsivity, cue reactivity or treatment success could also be useful in guiding prevention efforts (Ducci and Goldman, 2012). Impulsivity has been associated with genotypes that predict reduced 5-HT function (Bevilacqua, et al., 2010; Bevilacqua and Goldman, 2013; Bjork, et al., 2002; Stoltenberg, et al., 2012) and we have recently demonstrated that cocaine-dependent subjects who carry a SNP in the HTR2C (rs6318) (Lappalainen, et al., 1995) predicted to alter 5-HT2CR functionality (Brasch-Andersen, et al., 2011; Kuhn, et al., 2004; Okada, et al., 2004; Walstab, et al., 2011), exhibit significantly higher attentional bias on the cocaine-word Stroop task. As convergent evidence links genotypes to phenotypes important in addictive processes, it will be possible to best understand the shared genetic liability for impulsivity and cue reactivity, and to integrate this information into more effective clinical care for afflicted patients.

The development of biomarkers or predictors for vulnerability to addictive disorders will be of immense help in facilitation of treatment goals. Importantly, the advancement toward an armamentarium of medications that are effective and accessible means to suppress relapse (Volkow, et al., 2009) is necessary to improve the health outcomes of cocaine-dependent individuals. There has been little attention to the possibility that selective serotonergic medications may be of use in this regard, in large part because of the lack of such compounds for clinical trials in cocaine dependence. The SSRIs (e.g., fluoxetine) have been most studied and are largely ineffective as treatment in outpatient cocaine-dependent subjects as measured by outcomes of treatment retention, cocaine-positive urines or reductions in craving (Covi, et al., 1995; Grabowski, et al., 1995). However, Moeller and colleagues found that the SSRI citalopram in combination with cognitive behavioral therapy and contingency management significantly reduced cocaine-positive urines in citalopram-treated subjects who exhibited high baseline impulsivity scores (Green, et al., 2009; Moeller, et al., 2007; Schmitz, et al., 2009); these subjects remained in the study significantly longer than those that received placebo, reversing the negative correlation between the degree of baseline impulsivity and time in retention (Green, et al., 2009; Moeller, et al., 2001b; Moeller, et al., 2007; Patkar, et al., 2004; Schmitz, et al., 2009). These findings are consistent with a shared role for serotonergic substrates in impulsivity and cocaine relapse phenomenon and suggest that serotonergic strategies may be particularly effective in the impulsive subpopulation of cocaine addicts.

Several explanations are plausible for the inconsistency in the observations seen with citalopram versus other SSRIs in cocaine dependence. First, the SSRIs are a heterogeneous group of drugs that exhibit notable affinity for SERT and potently inhibit 5-HT reuptake, but differ with regard to relative affinities at the DA transporter (DAT) and norepinephrine (NE) transporter (NET), onset of therapeutic actions and half-life, and pharmacokinetic and metabolic profiles (Hiemke and Hartter, 2000; Vaswani, et al., 2003). Second, the fact that citalopram is a highly selective SSRI (3,400-fold higher affinity for SERT over NET or DAT) (Owens, et al., 1997) may contribute to the improved outcomes in cocaine-dependent subjects (Green, et al., 2009; Moeller, et al., 2001b; Moeller, et al., 2007; Patkar, et al., 2004; Schmitz, et al., 2009). The pharmacological profiles of SSRIs also includes moderate to high affinity for some 5-HT receptors. In particular, fluoxetine binds to the 5-HT2CR and acts as a potent 5-HT2CR antagonist (Ni and Miledi, 1997; Palvimaki, et al., 1996). Given that a selective 5-HT2CR antagonist (SB242084) enhances impulsive action (Fletcher, et al., 2007; Winstanley, et al., 2004b; Young, et al., 2011), cocaine-seeking (Burbassi and Cervo, 2008; Burmeister, et al., 2004; Fletcher, et al., 2002; Manvich, et al., 2012; Neisewander and Acosta, 2007; Pelloux, et al., 2012) and supports self-administration in non-human primates (Manvich, et al., 2012), fluoxetine actions as a 5-HT2CR antagonist may contribute to its failure to reduce craving and increase retention in treatment (Covi, et al., 1995; Grabowski, et al., 1995). Citalopram exhibits in vivo effects consistent with prominent actions as a 5-HT2CR agonist which are dose-dependently blocked by selective 5-HT2CR antagonists (Millan, et al., 1999; Palvimaki, et al., 2005). Third, a curious consequence of citalopram exposure may also contribute to its prominent actions as a 5-HT2CR agonist in vivo. A single injection of citalopram (20 mg/kg) was shown to rapidly upregulate 5-HT2CR binding sites in rat choroid plexus, an effect which is even more pronounced after chronic citalopram treatment (Palvimaki, et al., 2005; Palvimaki, et al., 1996). An increased density of 5-HT2CR after citalopram would allow 5-HT itself to exert greater actions via the 5-HT2CR and might account for the observations that the behavioral effects of citalopram fit the profile of a 5-HT2CR agonist moreso than do those of other SSRIs (Palvimaki, et al., 2005). In keeping with this hypothesis, fluoxetine does not alter the density of 5-HT2CR possibly due to its actions as a 5-HT2CR antagonist (Palvimaki, et al., 2005). Therefore, we propose that the treatment successes observed with citalopram (Green, et al., 2009; Moeller, et al., 2007; Schmitz, et al., 2009) over fluoxetine (Covi, et al., 1995; Grabowski, et al., 1995) in cocaine-dependent subjects may be related to the efficacy of citalopram to mimic selective 5-HT2CR agonists to suppress impulsivity (and perhaps cue reactivity) (Table 1).