Abstract

Factor VIII (FVIII) is the blood coagulation protein which when defective or deficient causes for hemophilia A, a severe hereditary bleeding disorder. Activated FVIII (FVIIIa) is the cofactor to the serine protease factor IXa (FIXa) within the membrane-bound Tenase complex, responsible for amplifying its proteolytic activity more than 100,000 times, necessary for normal clot formation. FVIII is composed of two noncovalently linked peptide chains: a light chain (LC) holding the membrane interaction sites and a heavy chain (HC) holding the main FIXa interaction sites. The interplay between the light and heavy chains (HCs) in the membrane-bound state is critical for the biological efficiency of FVIII. Here, we present our cryo-electron microscopy (EM) and structure analysis studies of human FVIII-LC, when helically assembled onto negatively charged single lipid bilayer nanotubes. The resolved FVIII-LC membrane-bound structure supports aspects of our previously proposed FVIII structure from membrane-bound two-dimensional (2D) crystals, such as only the C2 domain interacts directly with the membrane. The LC is oriented differently in the FVIII membrane-bound helical and 2D crystal structures based on EM data, and the existing X-ray structures. This flexibility of the FVIII-LC domain organization in different states is discussed in the light of the FVIIIa-FIXa complex assembly and function.

Keywords: coagulation Factor VIII, cryo-electron microscopy, structure determination, molecular modeling, protein–lipid interactions

INTRODUCTION

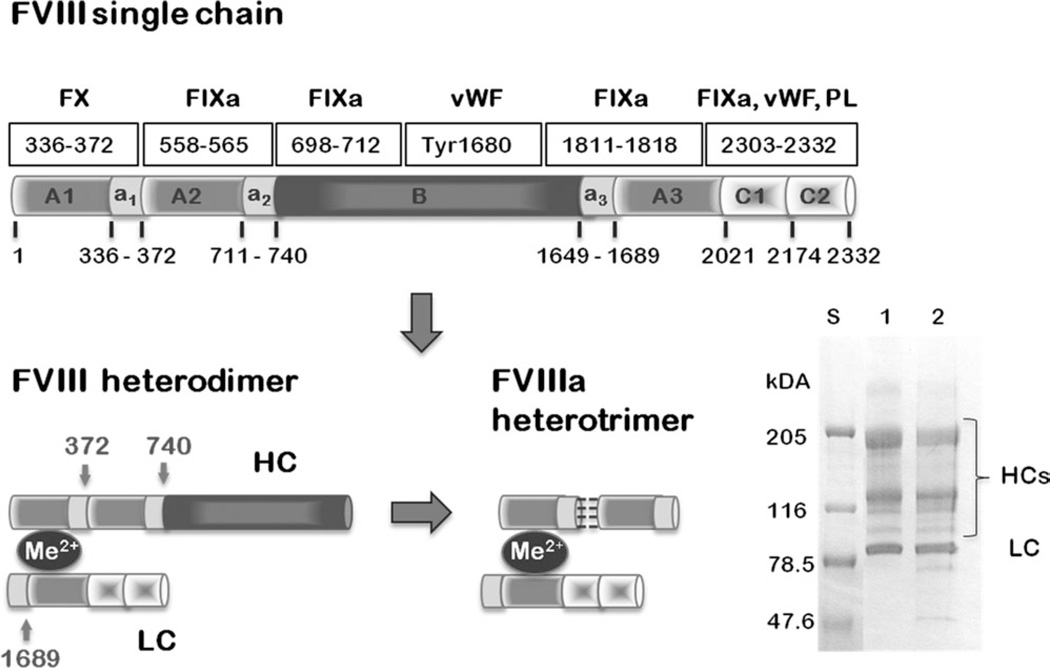

Factor VIII (FVIII) is a large plasma glycoprotein of 2332 amino acid residues organized in six domains: A1-A2-B-A3-C1-C2.1–4 The three A (3A) domains are homologous to each other, to the A domains of Factor V (FV), and the copper-binding protein ceruloplasmin.5 The B domain has no known homologues and the C domains are homologous to each other, to the C domains of FV, and are part of the discoidin family.6 In vitro, FVIII exists as a mixture of heterodimers of a variable length heavy chain (HC) of the A1–A2 domains with different length of the B domain due to limited proteolysis of the B domain by FXa or Thrombin, and a constant length light chain (LC). The LC consists of the A3–C1–C2 domains and holds the FVIII membrane-binding sites. The C2 domain has the main membrane-binding site to the negatively charged platelet surface identified as four hairpin loops interacting directly with the membrane. 6,7 The LC and HC are linked noncovalently via divalent metal cations. Upon initiation of coagulation, FVIII is further activated by thrombin, resulting in the entire cleavage of the B domain and separation of the A2 and A1 domains at Arg372. Thus, activated FVIII (FVIIIa) is a heterotrimer of the A1 and A2 domains and the LC. The A2 domain, which contains the main protease [Factor IXa (FIXa)]-binding sites, is linked noncovalently to the A1 domain by weak hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions. The FVIIIa has a short lifetime in vivo (~6 h) due to spontaneous dissociation of the A2 domain, leading to inactivated FVIIIa and abolished thrombin generation 9–12 (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

FVIII primary structure. FVIII single chain: the FVIII domains A1, A2, A3, B, C1, and C2 linear arrangement and amino acid numbering are shown. The acidic domains crucial for FVIII proteolytic activation are denoted as a1, a2, and a3. The main interactions sites with other coagulation factors: X, Xa, IXa, von Wlbrandt factor (vWF), and phospholipids (PL) are indicated with rectangular boxes, as well as the corresponding amino acid numbering. FVIII heterodimer: the gray arrows show the thrombin cleavage sites. The divalent metal ions (Me2+) holding the heavy chain (HC) and light chain (LC) are indicated with a dark ellipse. FVIIIa heterotrimer: the FVIII heterotrimer is held together by additional hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions between the A1 and A2 domains from the HC, shown as black dashed lines. SDS-PAA gel of the recombinant FVIII full length variant utilized in this study, which is identical to the plasma-derived FVIII utilized in the 2D crystals study13. FVIII-FL exists as a mixture of heterodimers with a constant LC of ~80 kDa molecular weight and variable HCs (90–200 kDa). The standards are indicated with S. 1-indicated the protein in the presence of 5 mM Ca2+ and with 2-the protein in the presence of 20 mM EDTA showing that the LC remains intact after treatment with 20 mM EDTA.

Two human recombinant FVIII crystal structures (FVIII-3D) lacking the B domain were solved by X-ray crystallography at 3.8 Å14 and 4.0 Å15 resolution. In the crystal structures, the C domains are juxtaposed to each other and proposed to both bind to the membrane. Following this domain organization, the well defined C2 domain membrane-binding interface including two pairs of hydrophobic residues from opposite hairpin loops: Met2199–Phe2200 and Leu2251– Leu2252, as well as Val2223 and His2315 from two additional C2 loops6,16,17 were extended to include Leu2053, Leu2096, Phe2093–Lys2092, and Gln2042–Phe2093 from the tip of the C1 domain.18–20 This FVIII–membrane interaction interface via both C domains includes the A3 domain from the LC in a proposed FVIII membrane-bound conformation within a model of the membrane-bound FVIIIa–FIXa complex.15,17 In the previous low-resolution FVIII membrane-bound structure (15 Å) from electron microscopy (EM) data of plasmaderived B domainless FVIII organized in two-dimensional (2D) crystals, only the C2 domain interacts directly with the membrane and the proposed FVIIIa–FIXa membrane-bound structure did not involve additional FVIII-LC membrane interaction sites.21 So far, it has been challenging to identify unambiguously which domains and residues from the FVIII-LC interact directly with the membrane in its functional membrane-bound conformation. Extensive biochemical studies have further confirmed the possibility of a dual C1–C2 membrane-binding interface.20,22 These data however do not exclude additional structurally allowed reorganization of the FVIII-LC domains in a membrane environment leading to a full FVIII-LC membrane-interaction including all LC domains (A3–C1–C2)15 or a sole FVIII-C2 membrane interaction.6,21

To advance our understanding of how the FVIII-LC and the entire FVIII membrane-bound organization affects the FVIII function and hemostasis, we have carried out cryo-EM and structural analysis of FVIII-LC bound to phosphatidylserine (PS) containing galactosylceramide (GC) single bilayer lipid nanotubes (LNTs)23 mimicking the activated platelet surface. Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) is a powerful method to study the structure and assembly of biological macromolecules and their interactions specifically at the protein– lipid bilayer interface.24,25 GC–LNT have been developed as suitable systems for helical crystallization of membrane-associated proteins allowing structure determination by cryo-EM in the 20–10 Å resolution range.25,26 At this resolution, the existing structural data for individual domains can be fitted and modeled within the protein densities defined by cryo-EM.27–29

In this work, we show the structure of membrane-bound FVIII-LC (FVIII-LC–LNT) as calculated from cryo-EM data of helically organized FVIII-LC onto PS-GC–LNT. The protein density map refined at 20 Å resolution supports the previously determined domain organization from FVIII membrane-bound 2D crystals,21 where the A3–C1–C2 domains have an extended arrangement and only the C2 domain interacts with the membrane. The C1 and C2 domains orientation is further altered in the new FVIII-LC–LNT structure to best fit the protein densities defined by cryo-EM. The orientation of the membrane-bound FVIII-LC domains in the helical crystals confirms the flexibility of the C1–C2 link identified from the 3D crystal structures14,15 showing the agonistic, rather than antagonistic nature of the FVIII-LC-membrane-bound organization defined for helical and 2D crystals to the one in FVIII-3D crystals (from X-ray crystallography). Defining the conformational space of the C2 and C1 domains orientation in different crystal packing: helical, 2D and 3D and respective to the rest of the FVIII molecule, is essential to understand the FVIII membrane-bound structure and its significance for hemostasis. Resolving the membrane-bound organization of the FVIII-LC is a critical component in understanding the FVIIIa–FIXa complex assembly onto the activated platelet membrane and its function. The new FVIII–LNT membrane-bound structure based on the FVIII-LC–LNT cryo-EM data is a step further in understanding the mechanism by which the FVIIIa–FIXa complex regulates the delicate equilibrium between excessive bleeding (hemophilia) and thrombosis.

RESULTS

Cryo-EM of FVIII-LC–LNT

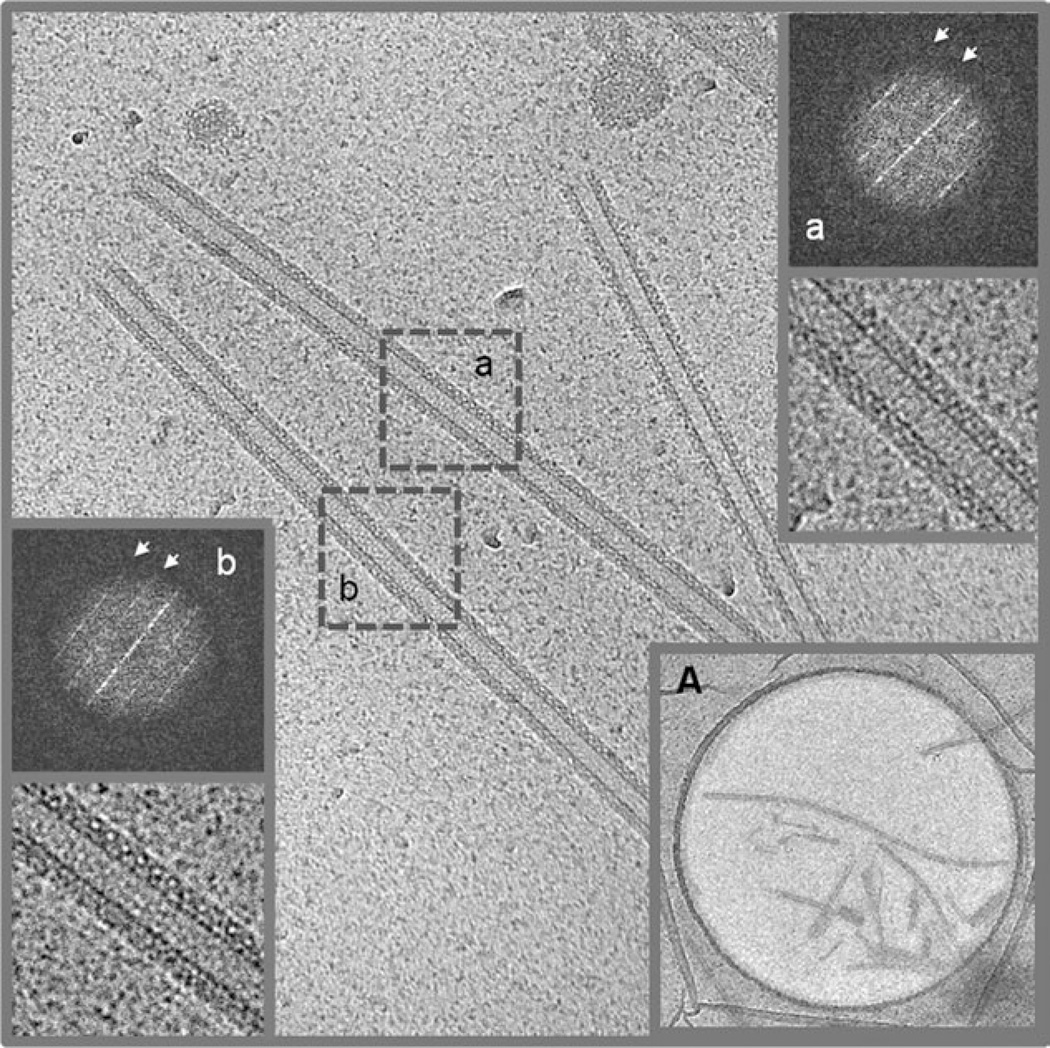

FVIII-LC and HC are completely dissociated in the presence of 20 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and only the FVIII-LC, which contains the FVIII membrane-binding sites is attached to the membrane.8,13 FVIII-LC binds tightly to the LNT in presence of 20 mM EDTA, fully covering the membrane surface (Figure 2). From a total of 229 FVIII-LC– LNT digital cryo-EM micrographs, 136 were selected and only 69 FVIII-LC–LNT images with defined helical diffraction were kept for further structure analysis.

FIGURE 2.

Digital cryo-EM micrograph of FVIII-LC–LNT (4096 × 4096 pixels at 2.9 Å/pixel). The inner tubes’ diameter is 190 Å. The length varies from 0.5 µm to a few micrometer. (a and b white) Fourier transforms (FTs) and inverse FT of the 512 × 512 pixel boxed area are denoted with a gray dashed line (a and b black). The two visible layer lines on the FT are centered at 0.0083 Å−1 and 0.0167 Å−1 (white arrows), respectively. The defocus of the images included in the dataset is between −0.7 µm and −4.4 µm, as calculated from the first Thon ring of the FT of the individual images with an overall average value of −2.5 ± 1.2 µm. (A) Low-magnification view of FVIII-LC–LNT. The FVIII-LC–LNT are frozen hydrated in amorphous ice over 2 µm diameter holes spaced 2 µm. The lipid and protein densities are in black.

Structure Analysis of FVIII-LC–LNT

FVIII-LC–LNT 2D Class Averages

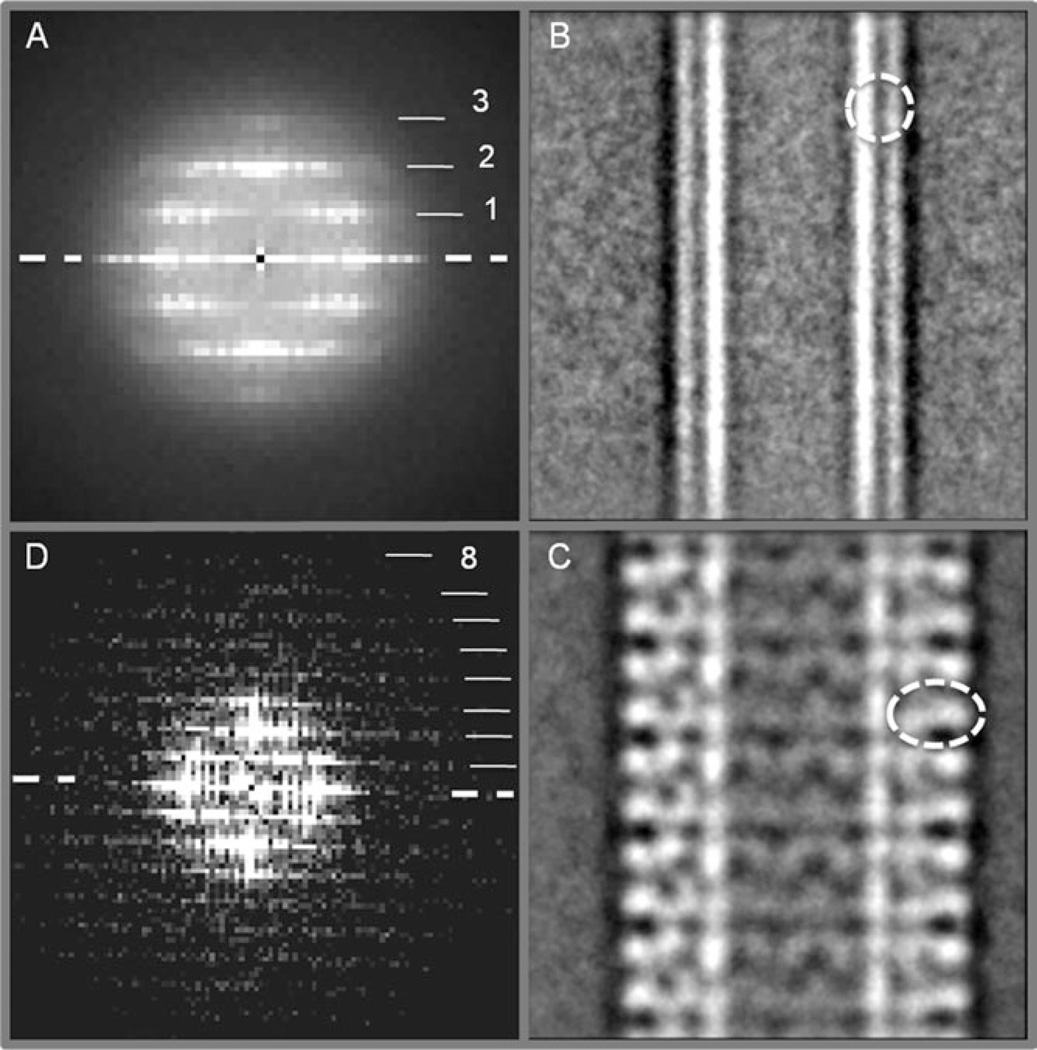

The cryo-EM micrographs were filtered, normalized, and inverted for further data analysis in the e2workflow.py graphic interface.30 The FVIII-LC–LNT helical tubes were selected and 256 × 256 pixels (at 2.9 Å/pixel) segments with 90% overlap boxed with e2helixboxer.py.30 Contrast transfer function (CTF) correction (only phase flipping) of the helical segments from the same micrograph was carried out and an initial particle (helical segments) set of 6408 particles was generated in the e2workflow.py interface single particle analysis option (EMAN2).30 Reference free 2D class averages were calculated with e2refine2d.py reference free alignment algorithm to select particles by diameter and degree of order. The diameter was evaluated from the 2D class averages and the order from the Fourier transform (FT) of the class averages within the e2display.py graphic interface (Supporting Information 1). The helical segments from class averages with inner diameter of 190 Å and consistent helical diffraction pattern were further combined in a single dataset. The process was iterated several times until a final set of 2043 particles was selected and a combined FT calculated to evaluate the helical parameters of the FVIII-LC–LNT for further structure analysis. The pitch was estimated at 120 Å and the rise at 60 Å (Figure 3A).

FIGURE 3. 2D analysis of FVIII-LC–LNT.

A. Combined FT from 2043 FVIII-LC–LNT helical segments (particles). The layer lines are indicated as 1—1/120 Å−1, 2—1/60 Å1, and 3—1/40 Å−1. The equator is indicated with a white dashed line. (B) Representative 2D class average from 277 control LNT (cLNT) segments with the same lipid composition as in (C) (Supporting Information 1). The lipid bilayer is well defined. The inner and outer leaflet and the lower density of the membrane hydrophobic core are clearly visible. The circle (white dashed line, 75 Å diameter) indicates the lipid bilayer. The inner diameter of the cLNT is 175 Å. (C) Representative 2D class average from 184 FVIII-LC–LNT particles (Supporting Information 1). The inner diameter of the FVIII-LC–LNT is 190 Å. The oval (white dashed line, 115 Å × 75 Å) indicates the 2D-projected density of the FVIII-LC-molecules oriented orthogonally to the lipid bilayer. The 2D class averages in (B) and (C) are cropped to 240 × 240 pixels at 2.9 Å/pixel. (D) FT of (C) showing up to eight layer lines (8—1/15 Å). The equator is indicated with a white dashed line. (A) and (D) are cropped views of the full FT of the helical segments.

The projected density of the FVIII-LC molecules in the 2D class averages oriented orthogonally to the LNT surface is well defined (Figure 3C). The inner leaflet of the LNT bilayer is clearly visible and corresponds to the density of the inner leaflet of the lipid bilayer defined in the control LNT (cLNT) 2D class averages (Figure 3B). The height of the helically organized FVIII-LC molecule was estimated to be ~75–80 Å above the membrane surface. The change in the inner diameter of the LNT upon binding and helical organization of the FVIII-LC further supports a strong protein–membrane interaction and possible partial insertion of the protein into the membrane bilayer (Figure 3B and C). These observations are in agreement with our previous work on the Factor Va (FVa)31 and FVIII membrane-bound structures. Some of the best class averages (Figure 3C) showed a twofold symmetry, viewed perpendicular to the long LNT axis. This symmetry was not taken into account for the helical reconstruction, due to the limited number of initial particles (helical segments) showing this feature. The 2D averages solely were used to classify the helical segments according to the reference free alignment algorithms and differentiate by diameter and order. For the helical analysis the individual particles were aligned according to the rise, rise per subunit angle and imposed symmetry (along the long LNT axis) following the single particle and helical algorithms implemented in the iterative helical real space reconstruction (HRSR).27,28

FVIII-LC-LNT Helical Reconstruction

3D reconstruction from the selected 2043 FVIII-LC–LNT helical segments was carried out with the IHRSR algorithm combining single particle and helical analysis. 27,28 A hollow cylinder with walls corresponding to the thickness of the lipid bilayer with the attached protein molecules was used as an initial reference volume (inner diameter = 190 Å, outer diameter = 550 Å, Supporting Information 2/Figure 1). To correctly define the symmetry of the FVIII molecules organized around the LNT we have tested 10 symmetries from 7 to 16 molecules for a 120 Å pitch and low initial angle, corresponding to the first layer line from the combined FT of the 2043 particle set (Figure 3A; Supporting Information 2/Figure 2). The symmetries to be tested were calculated from the possible number of FVIII molecules, which can be accommodated on a LNT surface with outer diameter of 300 Å and length 120 Å. Only symmetries, which gave 3D reconstructions with well-defined inner leaflet of the LNT bilayer and protein densities corresponding to the mass and volume of a membrane-bound FVIII or FVa: 80 Å × 60 Å × 40 Å,13,31,32 were considered for further evaluation. 15-fold symmetry proved to be best for a 120 Å pitch. The 3D reconstruction was further improved by refining 7.5 molecules FVIII-LC per 60 Å rise symmetry until the helical parameters converged (Supporting Information 2/Figure 2). The final FVIII-LC-LNT 3D reconstruction showed a helical repeat of 7.5 FVIII-LC molecules bound around the surface of a LNT segment with 60 Å length (rise) equivalent to 15 FVIII-LC molecules organized around a LNT segment of 120 Å length (Figure 4). This arrangement is in very good agreement with the estimated surface covered by one membrane-bound FVIII molecule organized in 2D crystals (~7200 Å2) and the surface of a naked LNT with a 300 Å outer diameter, which gives 15 FVIII molecules, organized around the LNT surface for a 120 Å pitch. In the FVIII-LC–LNT 3D helical reconstruction, the inner leaflet of the lipid bilayer is well defined, whereas the lipid molecules from the outer leaflet appear to strongly interact with the FVIIII-LC bound molecules. This feature of the FVIII-membrane-bound organization has been previously observed in our cryo-EM experiments with membrane-bound FVIII 21,23 and FVa31 and further validates the FVIII-LC–LNT cryo-EM structure (Figure 4). In the raw cryo-EM data the projected densities of the membrane-bound FVIII-LC molecules interfere with the outer membrane layer density showing apparent vacancies in the 3D reconstruction where the hydrophobic core is. This interference from the projected density is least at the outer surface of the protein (Figure 4A). The final 15 unit (FVIII-LC molecules)/120 Å pitch 3D reconstruction gave the best results when comparing the distribution of the particles per projection of the 3D helical volumes, as well as when comparing the 2D projections from the calculated 3D volume to the 2D class averages, where no symmetries are imposed (Supporting Information 2/Figure 3). Several consecutive cycles of refinement (50 cycles each) were carried out until convergence of the helical parameters: rise and angle was achieved (Supporting Information 2/Figure 2).

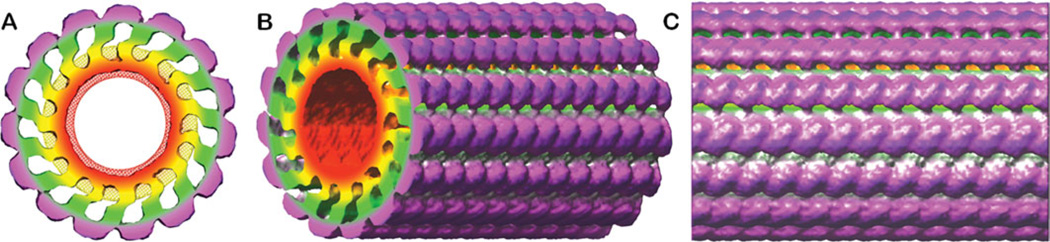

FIGURE 4.

3D reconstruction of FVIII-LC-LNT. (A) Orthorhombic view along the long LNT axis (z-axis). The solid surface is contoured at 0.005 density level and viewed at 5.8 Å/pixel resolution in Chimera—volume viewer option33. The surface is colored as follows (radius of outer shell from center): red—114 Å and yellow—162 Å are the densities corresponding to the LNT bilayer (red is the inner membrane layer). The FVIII-LC membrane-binding part is colored in green—198 Å and the FVIII-LC part not involved in the membrane binding is in magenta—250 Å. The tube inner diameter is 190 Å and the outer diameter 500 Å. The density corresponding to a cLNT is shown with red and yellow mesh (2.9 Å mesh size) contoured at 0.05 threshold with the same radii as for the FVIII-LC-LNT. (B) View rotated 45° and (C) 90° counterclockwise from (A) around the z-axis. The length of the tube corresponds to the boxed FVIII-LC-LNT segments: 256 pixels (2.9 Å/pixel) equal to ~12 turns of the FVIII-LC helix around the LNT, as the symmetry of the FVIII-LC-LNT helix is 7.5 subunits (FVIII-LC) molecules per turn (pitch = 60 Å = 20.7 pixels).

The resolution defined from the visible layer lines further way from the meridian in the FT of the best class averages (Figure 3C) is 15 Å. The resolution of the final FVIII-LC–LNT 3D reconstruction is limited to 20 Å because of the low signal to noise ratio of the protein density (low threshold) due to the relatively low number of helical segments in the initial dataset and local disorders in the FVIII-LC–LNT helical tubes. The densities corresponding to the membrane and membrane-bound region of the FVIII-LC molecule were sufficiently well defined to allow further fitting of the FVIII-LC domains’ atomic structures within the cryo-EM map.

Membrane-Bound Organization of FVIII Assembled in 2D Crystals

The original FVIII-2D membrane-bound structure21 was built by separately fitting the FVIII 3A domains homology model based on Ceruloplasmin X-ray structure,5 the C1 homology model based on the C2 crystal structure6 and the C2 crystals structure6 within the density for the membrane-bound FVIII-2D crystals calculated by EM.21 To improve the original FVIII-2D structure21 based on the new FVIII-3D structure (3CDZ), we first aligned separately the 3CDZ 3A domains: Ala1–Tyr2017, the C1 domain: Cys2021-Cys2169 and C2domain: Cys2174 to Tyr2332 to the FVIII-2D 3A and two C (2C) domains (Supporting Information 3/Fgure 1). The two peptide links between the A3 and C1 domains: SerAsn-Lys (2018–2020), and the C1 and C2 domains: Asp-LeuAsn-Ser (2170–2173) from the 3CDZ structure was separately aligned to the old FVIII-2D structure and a FVIII-2D reference structure based on the aligned 3CDZ structure was created in UCSF-Chimera.33 The reference FVIII-2D structure was exported in VMD34 and refined by aligning again the 3CDZ structure to the reference structure without separating the individual domains and by relaxing the A3–C1 and C1–C2 links. To achieve this, first the 3CDZ-3A domains were aligned to the reference structure 3A domains, and then the 2C domains were consecutively aligned, keeping the 3A domains fixed by relaxing the peptide links between the A3– C1 and the C1–C2 domains imposing independent rotation and translation of the respective domains. The new FVIII-2D structure was compared with the old FVIII-2D structure and to the FVIII-3D structure showing that both FVIII-2D structures, based on homology modeling (old) and FVIII-3D structure (new), are permitted (Figure 5; Supporting Information 3/Figure2).

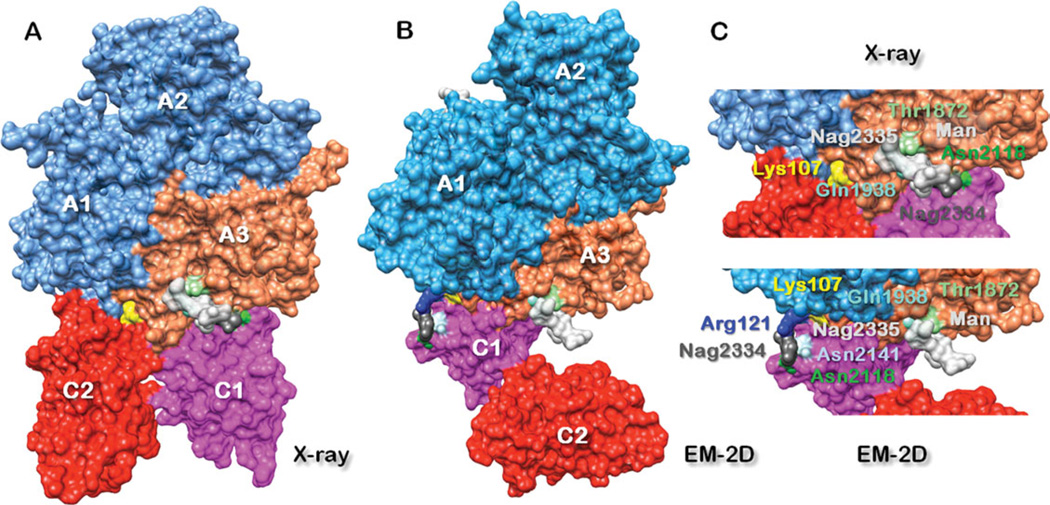

FIGURE 5.

FVIII domain organization in 2D and 3D crystals. (A) Domain organization of FVIII in 3D crystals as solved by X-ray crystallography (3CDZ). In the FVIII-3D structure two N-acetyl glucosamines: Nag2334 and Nag2335 (dark and light gray spheres) and three manose residues: Man2336–2338 (light gray spheres) are in close proximity to Asn2118 (green spheres) at the C1–A3 interface.14,15 (B) Domain organization of FVIII in 2D crystals as proposed by EM. In the FVIII-2D structure the Asn2118 is moved to the C1–A1 interface, due to the rearrangement of the C domains respective to the 3A domain in the 2D crystal structure. The Nag2334 (dark gray spheres) is also moved with the Asn2118 to the C1–A1 interface and is stabilized additionally by Arg121 (blue spheres) from the A1 domain and Asn2141 (light blue spheres) from the C1 domain. The NAG2335 (light gray spheres) remains at the C1–A3 interface in proximity to Gln1938 (aquamarine spheres) and Thr1872 (light green spheres) from the A3 domains, as originally resolved in the FVIII-3D structure. The FVIII structures in (A) and (B) are aligned on the 3A domains, as previously shown.14 (C) Magnified view of the C—A domains interface. Top: C1–A3 and C2–A1 domains interface in the FVIII-3D structure and bottom: C1–A3 and C1–A1 interface in the FVIII-2D structure. The A1 domain is colored blue, the A3 orange, the C1 magenta, and the C2 red. In the FVIII-3D structure, the Nag2335 at the C1–A3 interface (top) is in proximity to three mannose residues (Man 2336, 2337, and 2338 light gray spheres). We cannot assert at this point whether the mannose residues and NAG2335 remain at the C1–A3, as resolved in the FVIII-X-ray structure.

The new FVIII-2D structure based on the 3CDZ co-ordinates shows an important glycosylation site resolved in the X-ray structure: Asn2118 from the C1 domain localized at the C1–A3 domains interface (Figure 5). The Asn2118 in the FVIII-2D structure is located at the C1–A1 interface stabilized by the NAG2334 and Arg121 from the A1 domain (Figure 5C). The rearrangement of the C1 domain, respectively, to the A1 and A3 domains in the FVIII-2D structure is not in contradiction with the FVIII-3D structure, as the C2– A1 interface characterized in the FVIIII crystal structure is small (~371 Å2) and supported by weak interactions: only Arg121 and Glu122 from the A1 domain are sufficiently close (~5 Å) to Gln2266 and Lys2239 from the C2 domain to allow hydrogen bonds and electrostatic interactions between the amino acid residues’ side chains.15 All the remaining amino acid residues at the A1–C2 interface are at a distance greater than 8 Å. This reorganization of the C1–A3 interface is allowed by the flexibility of the link between the C1 and C2 domains and weak hydrophilic interface between them. 14, 15 The C1 domain in the FVIII-2D structure forms a stronger interface with the A1 domain, compared to the weaker interface between the C2 and A2 domains in the FVIII-3D structure (Figure 5). In the FVIII-2D structure, Lys107 and Glu177 from the A1 and Glu2022 and His2137 from the C1 domain are closer than 4 Å, respectively, allowing van der Waals interactions between the side chain atoms. Arg121 from A1 and Asn2118 from C1 are also in close proximity ~5 Å further reinforcing the A1–C1 interface. The A3–C1 domain interface has been well characterized for both FVIII-3D and FVIII-2D structures showing an extended 1200 Å2 hydrophobic and aromatic interface14,15,21 (Figure 5C).

Fitting of FVIII-LC Domains Within FVIII-LC-LNT Density Defined by cryo-EM

To fit FVIII-LC from the 2D and 3D crystal structures within the FVIII-LC-LNT cryo-EM map, both structures were oriented with the C2 domain facing the LNT membrane, such that the residues Phe2200 and Leu2252 from the hairpin loops interact directly with the membrane (Supporting Information 3/Figure 3). All structures were fitted automatically with the “fit in map” option of UCSF Chimera 34,35 until convergence was achieved. Few initial positions were selected to differentiate between multiple fitting options, restricting the orientation of the C2 domain toward the membrane. The best fit for the FVIII-LC-3D structure did not accommodate both C domains within the cryo-EM map. The FVIII-LC-2D structure showed a better fit, however the C2 domain did not fit correctly the corresponding density from the FVIII-LC–LNT cryo-EM map (Figure 6; Supporting Information 3/Figure 3).

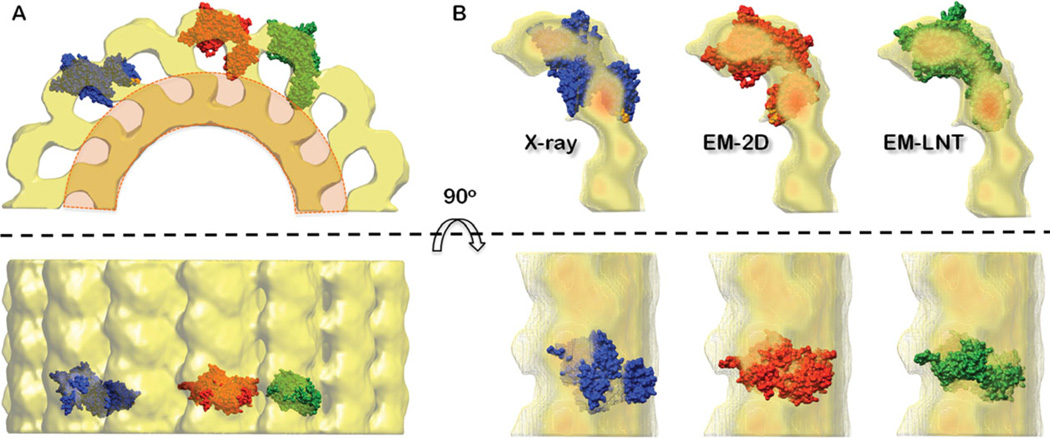

FIGURE 6.

Fitting of the FVIII-LC within the FVIII-LC–LNT protein–membrane density defined by cryo-EM. (A) Surface representation of half of the FVIII-LC–LNT 3D density map calculated from the cryo-EM data, drawn at 2.9 Å/pix and 0.004 contour level. The FVIII-LC-3D (blue), the FVIII-LC-2D (red), and the FVIII-LC–LNT (green) structures are shown as surfaces and fitted with the “fit in map” option of UCSF Chimera (Supporting Information 3, Table I). The density corresponding to the cLNT membrane is shown in orange. The orthogonal fitting of the FVIII-LC-3D structures is not allowed as it interferes with the density of the adjacent molecule as seen in (B). (B) Combined surface and solid density maps of two adjacent FVIII-LC–LNT molecules. In red is the density corresponding to 0.019 thresholds and in yellow to 0.009 (map density: min = 0.0, max = 0.02). The FVIII-LC-3D (red), FVIII-LC-2D (blue), and FVIII-LC–LNT (green) structures are fitted as in (A). Phe2200 and Leu2252 from the C2 domain hairpin loops interacting directly with the membrane are shown with orange spheres.

To optimize the fitting of the FVIII-LC from the FVIII-2D structure the A3–C1 and C2 domains were separately fitted within the cryo-EM map, keeping the correct C2 orientation toward the membrane. The A3–C1 domains interface was kept as in the FVIII-2D structure. The C2 domain was rotated around the flexible C1–C2 link: Asp2170-Ser2173 for an optimal fit, resulting in a more elongated orientation of the 2C domains. The resulting FVIII-LC–LNT membrane-bound structure showed a better fit within the cryo-EM map (Supporting Information 3/Figure 3).

Membrane-Bound Organization of FVIII Assembled in Helical Crystals

The new FVIII-LC–LNT structure was generated based on the FVIII-LC–LNT structure obtained from the rigid docking of the FVIII-LC domains atomic structures within the cryo-EM map. A reference FVIII-LC–LNT structure was first created in UCSF Chimera and then exported in VMD. 34 In VMD, the 3CDZ structure was aligned to the FVIII-LC–LNT reference structure, by first aligning the A3 domain, then the C2 domain, keeping the A3 domain fixed. Finally the C1 domain was aligned keeping both A3 and C2 fixed.

The links between the A3–C1 and C1–C2 domains were relaxed accordingly to optimize the alignment. The FVIII-3A domains were aligned such as to match the orientation of the A3 domain in the FVIII-LC membrane-bound structure, by preserving their organization as in the FVIII-2D structure. The resulting FVIII–LNT structure showed that for the helically assembled FVIII-LC molecules, the conformation of the FVIII-LC is more extended (Figure 6; Supporting Information 3/Figure 3) than the FVIII-2D. This flexibility of the FVIII-LC structure in different ordered assemblies: helical, 2D and 3D crystals confirms the potential role of the FVIII-LC domains orientation to enhance the FIXa proteolytic efficiency when assembled with FVIIIa in the Tenase complex.

DISCUSSION

FVIII is a complex multidomain protein, which for function requires an elaborated interplay between two well-defined protein–protein and protein–lipids interfaces. Understanding the structural relationship between these two interfaces: the LC–membrane and the LC–HC, is fundamental to optimize the FVIIIa–FIXa interaction governing the Tenase complex assembly and function. Historically, first the C2–membrane interface was identified from the C2 crystal structure solved at 1.9 Å .6 Five hydrophobic residues from two β-hairpin loops: Met2199–Phe2200 and Leu2251–Leu2252, and Val 2223 from an adjacent loop were suggested to interact directly with the membrane. Fitting the C2 domain within the corresponding density for membrane-bound FVIII organized in 2D crystals showed a fourth loop exposing Trp2313 and His2315 as a direct-binding site to the membrane surface,21 confirmed recently by a crystal structure of the C2 domain in complex with a specific inhibitor.17 The same C2 domain membrane-binding interface was identified for the two FVIII crystal structures solved at 3.8 Å14 and 4.0 Å15 resolutions. The RMSD between the C2 domain alone6 and the C2 domain in the FVIII crystal structures is 0.79 Å and 1.5 Å, respectively.14,15 In both crystal structures the C domains are juxtaposed to each other and proposed to both bind to the membrane. This arrangement of the C domains has been also observed in the crystal structure for the homologous protein Factor Vai (resolved at 2.8 Å, lacking the B and A2 domains),35 which indicates that a juxtaposed C1–C2 organization is preferred in 3D crystal packing. In the crystal structures, the C2 domain is loosely bound to the adjacent A1 and C1 domains. 14, 15 Both C2–A1 and C1–C2 interfaces are rather hydrophilic (<400 Å2) and the C1–C2 link (Asp2170–Ser2173) allows a considerable degree of freedom. In contrast, the C1 domain forms an extended aromatic-hydrophobic interface with the A3 domain (~1200 Å2, 20 residues), which corresponds to the size of the A3–C1 interface calculated for the membrane-bound FVIII structure.21 Comparing the FVIII-2D to the FVIII-3D (3CDZ) structure shows that they are complimentary and differ in the organization of the LC domains, thus affecting the interfaces between the C domains and the membrane, as well as between the C and A3 domains (Figure 6A and B).

This fact was previously illustrated in the first paper reporting the FVIII-3D structure.14 Orienting the C1 domain from the FVIII-LC-3D structure to match the orientation of the C1 domain in the FVIII-LC-2D and FVIII-LC–LNT structures is allowed rotationally and translationally by relaxing the Ser2018–Lys2020 peptide linker between the A3 and C1 domains. The same hydrophobic A3–C1 interface was preserved for both membrane-bound forms (Figure 4). Orienting the C2 domain from the FVIII-3D structure such as to match the orientation in the FVIII-2D and FVIII–LNT structures, requires further translation and rotation, which is achieved by relaxing the Asp2170–Ser2173 peptide linker between the C1 and C2 domains (Figure 6). The two S–S bonds between Cys2021–Cys2169 and Cys21730–Cys2326, each positioned at the C1 and C2 domain ends, respectively, limit the length of the flexible peptide links and restrict the C1–A3 and C1–C2 domains conformational space. The FVIII-LC–LNT is a direct evidence for the flexibility of the FVIII molecule in its membrane-bound state and proof for the physical existence of the previously proposed FVIII-2D structure. Which FVIII structure (3D, 2D, or helical) is closest to the physiological membrane-bound organization of FVIIIa within the Tenase complex is yet to be resolved.

When calculating a 3D structure from 2D crystals by EM, the crystals need to be tilted in the electron microscope. This tilt is limited to 65–708 leading to a significant missing cone of information.36 In the case of membrane-bound FVIII 2D crystals, the missing information is in the direction parallel to the membrane involving mainly the C domains–membrane interface. For this reason the height and overall density distribution of the FVIII membrane-bound molecules attached to a phospholipid vesicles’ surface and viewed parallel to the membrane was considered when calculating the 3D structure. This orthogonal to the 2D crystals view clearly showed a small density, as a stalk connected to a larger density, corresponding predominantly to the mass of the 3A and the C1 domains,21 also observed for the FVa bound to phospholipid vesicles32 and tubes.23 The orientation of the A domains was well resolved from the projection map of the membrane-bound FVIII 2D crystals, however less information was available for the C domains, as they lay directly under the A domains heterotrimer, when viewed perpendicular to the membrane surface.13,21 This problem is overcome for helically organized FVIII bound to LNT, as all views of the membrane-bound FVIII molecules are present in the images recorded with no tilt and the best resolved structural information is obtained parallel to the membrane (defining well the C domains membrane-binding interface23,45). Therefore, 2C domains directly interacting with the membrane cannot fit within the electron densities obtained for helically organized FVIII-LC molecules, FVIII organized in 2D crystals and the density resolved for individual molecules attached to PS-containing vesicles.

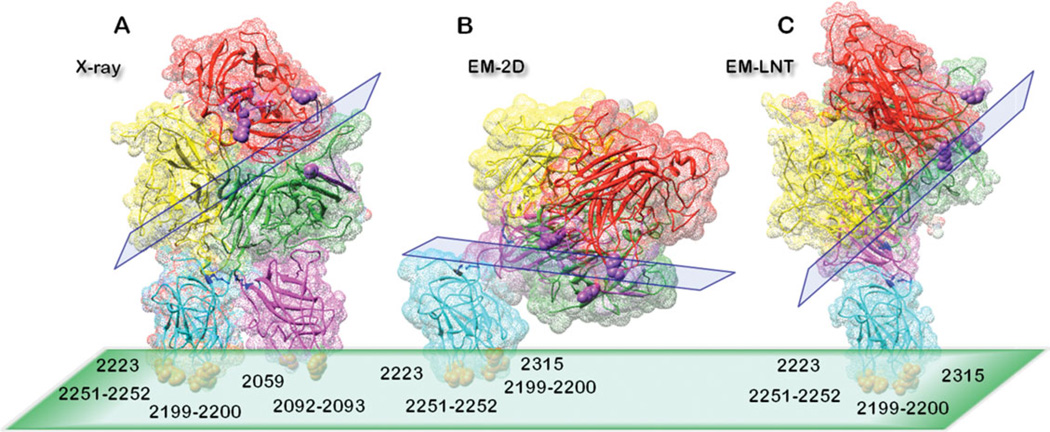

Recent biochemical studies have supported the importance of the C1 domain in the FVIII membrane-binding18–20 and shown that even removing the C2 domain does not completely abolish FVIII function.37 Our results do not exclude the juxtaposed C domains organization, or the biochemical evidence for the C1 domain binding and importance for the FVIII function. The presented novel FVIII-LC–LNT membrane-bound structure supports the previous FVIII membrane-bound structure from 2D crystals21 further confirming that there are at least two significant FVIII-LC domains organization at the level of the FVIII–membrane interface: one observed in 3D crystals with 60–70% water content and presence of crystallization agents14,15 where the C domains are juxtaposed and a second structure where only the C2 domain interacts with the membrane, as observed in tightly packed membrane-bound FVIII molecules organized in helical or 2D crystals at close to physiological conditions: solution and membrane composition (Figure 7). The membrane-bound FVIII structures from 2D and helical crystals are compatible with the FVIII-3D structures and the FVIIIa– FIXa interaction interface characterized so far. For example, the FVIII-2D structure supports an additional membrane-binding site at the A3 domain15 as the A3 domain is in close proximity to the membrane when organized in 2D crystal. At the same time the A2 domains is positioned at the right height (~9 nm)38 and orientation21 for the FVIIIa-FIXa interaction, without requiring a significant domain re-organzation (Figure 7). 15, 17 Finally, the suggested FVIII-C2-binding site for the FIXa-Gla domain 15,39 in the Tenase complex is not really accessible for the FVIII-2D and FVIII-3D structures, but easily reached in the refined FVIII-LNT structure with a stretched C2–C1 arrangement, where the C2 domains solely binds to the membrane and the C1 is position on top of the C2. The angle between the C1 and C2 domains’ long axis is close to a straight angle for the FVIII-LC–LNT and to a right angle for the FVIII organized in 2D membrane-bound crystals. The FVIII domains organization based on the FVIII-LC–LNT cryo-EM structure is also reminiscent of the first FVIII and FV membrane-bound models (the windmill model),40,41 which can be seen as the closest to the functional FVIIIa structure within the tenase complex (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7.

FVIII membrane-bound organizations. (A) FVIII-3D structure calculated from X-ray (3CDZ)15 oriented following the identified C2 and C1 membrane-binding residues. (B) FVIII-2D structure calculated from EM of membrane-bound FVIII-2D crystals.21 (C) FVIII–LNT structure calculated from helically assembled FVIII-LC onto LNT. The FVIIII domains are colored as follows: A1—yellow, A2—red, A3—green, C1—magenta, and C2—cyan. The C2 domains membrane-binding residues interacting directly with the membrane: Val2223, His2315, Met2199-Phe2200, and Leu2251–2252 are shown as orange spheres. (A) The C1 amino acid residues from the FVIII-3D structure interacting directly with the membrane: Ile2059 and Lys2092–Phe2093 are shown as orange spheres. The Factor IXa-binding loops A2: 558–565, 702–721 and A3: 1811–1818 are shown in purple and the critical residues for the FVIIIa–FIXa-binding interface: Lys1818, Lys713, and Arg562 are shown as purple spheres. The C1: Cys2021, Cys 2169 and the C2: Cys2174, Cys2326 residues forming disulfide bonds are shown in dark blue. The LC/membrane and HC/LC interfaces are shown as green and blue rectangles, respectively.

Identifying the exact residues from the FVIII-LC directly involved in the membrane binding has been the subject of numerous biochemical, biophysical and structural studies. Yet, the exact membrane-bound organization of FVIII has remained elusive specifically in the context of the Tenase complex assembly and function. The question of how this membrane-bound organization affects the HC–LC interface and modulates the FVIIIa cofactor activity within the FVIIIa–FIXa complex is not fully understood. The best known naturally occurring FVIII point and missense mutations, leading to hemophilia A are widely distributed across the FVIII molecules 14,44 suggesting that there is a very intricate and delicate allostery between the FVIII–membrane and the FVIII HC–LC interfaces leading to an optimal assembly of the FVIIIa–FIXa complex onto the platelet surface (Figure 7). It is also quite plausible that multiple conformations of membrane-bound FVIII and multiple conformational FVIIIa–FIXa assemblies exist, resulting in a range in efficiency of FIXa proteolytic amplification by FVIIIa. It is well known that a functional FVIIIa–FIXa complex can also form in solution; however its efficiency is greatly reduced compared to the FVIIIa–FIXa complex assembled on the activated platelet surface.43 Finally, remodeling the FVIII-2D structure based on the FVIII-3D co-ordinates shows that the Asn2118 residue, which is glycosilated and is localized at the C1–A3 domain interface 15 moves to a newly formed C1–A1 domain interface in the FVIII-2D structure (Figure 5). This new interface might be of significance for stabilizing the FVIIIa heterotrimer, which undergoes an additional cleavage between the A1 and A2 domains upon thrombin activation of FVIII,44 allowing the necessary flexibility of the A2 domain for optimal interaction with the FIXa.

To answer the fundamental question: “How the membrane-bound organization of the FVIII-LC affects the LC– HC interaction and modulates the FVIIIa cofactor activity within the FVIIIa–FIXa complex?” we need more structural information at different physiological conditions known to affect its function, as well as more consistent correlation with existing biochemical, biophysical and molecular biology data. A higher resolution FVIII membrane-bound structure by cryo-EM especially complemented with a FVIIIa and FVIIIa–FIXa complex membrane-bound structures, will be crucial to understand the exact nature of the FVIII–membrane interface, specifically in the context of the Tenase complex assembly and its role in hemostasis.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

FVIII-LC–LNT Preparation

GC: d-Galactosyl-b1–10-N-nervonyl-d-erythro-sphingosine (C24:1 β-d-galactosyl ceramide) and PS: DOPS—1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-[phospho-l-serine] were from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). The LNT were kept in: 20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, and pH 5 7.4. Albumin free human recombinant FVIII full length (FL; gift from Baxter Bioscience Vienna, Austria) was attached to the PS-GC–LNT [GC:PS = 1:4 (w/w)] ratio, prepared as previously described.23,45 EDTA of 20 mM was added to dissociate the FVIII-HC and incubated for 20 min at room temperature (21°C). The activity of FVIII was measured with the one stage aPTT-clotting assay (STart® Hemostasis Analyzer, Diagnostica Stago).46

Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE)

Ready Gel® Tris–HCl gels (4–15%; BioRad) were used. Protein of 10 µl at 0.4 mg/ml were reduced with 5% β-mercaptoethanol in Bio-Rad Laemmli sample buffer at 94°C for 5 min, loaded onto gels with Bio-Rad Prestained Standards Broad Range and run at 115 V for 2 h. The gels were stained with GelCode® Blue Stain Reagent (Thermo Scientific) and destained with water.

Electron Microscopy

Specimen preparation

FVIII-LC–LNT of 2µl was deposited onto hydrophilic EM holey carbon grids (R2/2, Quantifol MicroTools GmbH), the excess liquid blotted and the grids quickly plunged in liquid ethane cooled down by liquid nitrogen to obtain amorphous ice with the Vitrobot Mark III (FEI). The grids were transferred and observed at liquid nitrogen temperature in a transmission electron microscopy (TEM).

Data collection

Cryo-EM data were collected with a JEM2010F—field emission gun-equipped TEM operated at 200 kV. Images were recorded with a 4096 × 4096 pixel Ultrascan CCD camera (15 µm/pixel resolution, Gatan) at low electron dose conditions (~16 electrons/Å2s), liquid nitrogen temperature and a final magnification of 52,000 × on the detector. The quality of the helically organized FVIII-LC–LNT was evaluated in Fourier space with the FT option of the Digital Micrograph software utilized for the data collection (Gatan).

Image Analysis and Structure Determination

2D image analysis

The initial image processing was carried out with EMAN2.30 Helical tubes were selected with the e2helixboxer.py and processed in the single particle analysis option of the e2workflow.py interface, where CTF correction was carried out and the initial particle (helical segments) sets were created. 2D class averages were refined with the e2refine2d.py iterative reference free alignment algorithm implemented in EMAN2.30

Helical analysis

The final set of FVIII-LC–LNT segments (particles) was created in EMAN2 and validated for particles with the same diameter and order. The 3D reconstruction of the FVIII-LC-LNT was carried out with the IHRSR algorithm. 27 The final 3D reconstruction was validated according to the IHRSR criteria 27–29 and the biochemical, biophysical and structural data known for the membrane-bound FVIII-LC form.

Molecular Modeling

Modeling of the FVIII-2D structure

Modeling of the FVIII-2D membrane-bound atomic structure was carried out initially in the UCSF-Chimera software33 by individually aligning the 3A domains, the C1 and C2 domains from the FVIII-X-ray structure 15 to the existing FVIII-EM structure.21 The reference structure were imported into VMD and the new FVIII-2D structure refined by aligning first the FVIII-3D structure (3CDZ)15 3A domains and then the C1 and C2 domains, independently of each other. The links between A3–C1 and C1–C2 were further relaxed by rotation and translation of the individual domains to best match the reference structure. The residues were minimized in NAMD.47

Rigid body docking

Fitting of the FVIII-LC domains atomic co-ordinates within the FVIII-LC–LNT cryo-EM density map was carried out with the UCSF-Chimera “fit in map” algorithm.33 First, the C2 domain was fitted in the corresponding dxensity and then the A3–C1 domains preserving the A3–C1 interface. The fit was optimized with the “fit in map” option and the PDB co-ordinates saved as a reference in UCSF Chimera.33

Modeling of the FVIII-LC–LNT structure

The reference FVIII-LC–LNT structure was exported to VMD34 and refined by first aligning the A3 domain, then the C1 and C2 domains, respectively. The links between the A3–C1 and C1– C2 domains were brought into closer proximity of the domains by translating and rotating the residues, and, finally, the residues were relaxed by minimizing in NAMD.47 The whole FVIII–LNT structure was built in VMD based on the FVIII-LC–LNT structure keeping the orientation of the FVIII-HC respective to the LC as in the FVIII-3D crystal structure.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

SSM acknowledge Professor Wah Chiu, Director of National Center for Macromolecular Imaging, Baylor College of Medicine who provided the facility and support to carry out successfully this project, as well as critical reading of the manuscript and continuous encouragement in carrying out the FVIII–LNT project. The author acknowledges all the staff and faculty of NCMI for their support and the National Center for Research Resources grant P41RR02250 to Professor Wah Chiu and SL. SSM also acknowledge Professor Ed Egelman from the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, for providing the IHRSR software, critical support with the analysis and consulting. This work is supported by a National Scientist Development grant from the American Heart Association: 10SDG3500034 and UTMB-NCB start up funds to SSM. BMP and GCL were supported in part by the Robert A Welch Foundation and NIH R01 grant GM037657, to BMP. This work used the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE), which is supported by National Science Foundation grant number OCI-1053575 and a National Science Foundation grant (CHE1152876) to BMP.

Contract grant sponsor: NIH Center

Contract grant number: P41 GM103832 (Wah Chiu)

Contract grant ponsor: National Scientist Development grant from the American Heart Association

Contract grant number: 10SDG3500034

Footnotes

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Toole JJ, Knopf JL, et al. Nature. 1984;312:342–347. doi: 10.1038/312342a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vehar GA, Keyt B, et al. Nature. 1984;312:337–342. doi: 10.1038/312337a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kane WH, Davie EW. Blood. 1988;71:539–555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lenting PJ, Mourik JA, Mertens K. Blood. 1998;92:3983–9396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pemberton S, Lindley P, Zaitsev V, Xard G, Tuddenham EG, Kemball-Cook G. Blood. 1997;89:2413–2421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pratt KP, Shen BW, Takeshima K, Davie EW, Fujikawa K, Stoddard BL. Nature. 1999;402:439–442. doi: 10.1038/46601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meeks SL, Healey JF, Parker ET, Barrow RT, Laollar P. Blood. 2007;110:4234–4242. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-096842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wakabayashi H, Schmidt KM, Fay PJ. Biochemistry. 2002;41:8485–8492. doi: 10.1021/bi025589o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fay PJ. Blood. 2004;18:1–15. doi: 10.1016/s0268-960x(03)00025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pittman DD, Kaufman RJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2429–2433. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fay PJ, Smudzin TM. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:13246–13250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Derrick TS, Kashi RS, Durrani M, Jhingan A, Middaugh CR. J Pharm Sci. 2004;93:2549–2557. doi: 10.1002/jps.20167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stoylova SS, Lenting PJ, Kemball-Cook G, Holzenburg A. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:36573–36578. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen BW, Spiegel PC, Chang CH, Huh JW, Lee JS, Kim J, Kim YH, Stoddard BL. Blood. 2008;111:1240–1247. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-109918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ngo JC, Huang M, Roth DA, Furie BC, Furie B. Structure. 2008;16:597–606. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilbert GE, Kaufman RJ, Arena AA, Miao H, Pipe SW. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:6374–6381. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104732200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu Z, Lin L, Yuan C, Nicolaes GA, Chen L, Meehan EJ, Furie B, Furie BC, Huang M. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:8824–8829. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.080168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsu TC, Pratt KP, Thompson AR. Blood. 2008;111:200–208. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-068957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meems H, Meijer AB, Cullinan DB, Mertens K, Gilbert GE. Blood. 2009;114:3938–3946. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-197707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu J, Pipe SW, Miao H, Jacquemin M, Gilbert GE. Blood. 2011;117:3181–3189. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-301663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stoilova-McPhie S, Villoutreix BO, Mertens K, Kemball-Cook G, Holzenburg A. Blood. 2002;99:1215–23. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.4.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Novakovic VA, Cullinan DB, Wakabayashi H, Fay PJ, Baleja JD, Gilbert G. Biochem J. 2011;435:187–196. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parmenter CD, Stoilova-McPhie S. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;366:288–293. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.11.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muller SA, Aebi U, Engel A. J Struct Biol. 2008;163:235–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fujiyoshi Y, Unwin N. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2008;18:587–592. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson-Kubalek EM, Chappie JS, Arthur CP. Methods Enzymol. 2010;481:45–62. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(10)81002-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Egelman EH. J Struct Biol. 2007;5:83–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Egelman EH. Methods Enzymol. 2010;482:167–183. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(10)82006-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galkin VE, Schmied WH, Schraidt O, Marlovits TC, Egelman EH. J Mol Biol. 2010;396:1392–1397. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang G, Peng L, Baldwin PR, Mann DS, Jiang W, Rees I, Ludtke SJ. J Struct Biol. 2007;157:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stoilova-McPhie S, Parmenter CD, Segers K, Villoutreix BO, Nicolaes GA. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:76–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stoylova S, Mann KG, Brisson A. FEBS Lett. 1994;35:330–334. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00881-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petteresen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. J Mol Graphics. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adams TE, Hockin MF, Mann KG, Everse SJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8918–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403072101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henderson R, Unwin PN. Nature. 1975;257:28–32. doi: 10.1038/257028a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wakabayashi H, Griffiths AE, Fay PJ. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:25176–25184. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.106906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mutuccumarana VP, Duffy EJ, Lollar P, Johnson AE. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:23652–23657. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blostein MD, Furie BC, Rajotte I, Furie B. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31297–31302. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302840200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pellequer JL, Gale AJ, Getzoff ED, Griffin JH. Thromb Haemost. 2000;83:78–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pellequer JL, Gale AJ, Griffin JH, Getzoff ED. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 1998;24:448–461. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.1998.0214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kemball-Cook G, Tuddenham EG, Wacey AI. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:216–219. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.1.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gilbert GE, Arena AA. Biochemistry. 1997;36:10768–10776. doi: 10.1021/bi970537y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fay PJ, Jenkins PV. Blood Rev. 2005;19:15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parmenter CD, Cane MC, Zhang R, Stoilova-McPhie S. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:1657–1660. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lollar P. J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1:2275–2279. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Phillips JC, Braun R, Wang W, Gumbart J, Tajkhorshid E, Villa E, Chipot C, Skeel RD, Kale L, Schulten K. J Comput Chem. 2005;26:1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meng EC, Pettersen EF, Couch GS, Huang CC, Ferrin TE. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:339. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.