Abstract

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) antiviral therapy is plagued by limited efficacy and resistance to most nucleos(t)ide analog drugs. We have proposed that the complex RNA binding mechanism of the HBV reverse transcriptase (P) may be a novel target for antivirals. We previously found that RNA binds to the duck HBV (DHBV) P through interactions with the T3 and RT1 motifs in the viral terminal protein and reverse transcriptase domains, respectively. Here, we extended these studies to HBV P. HBV T3 and RT1 synthetic peptides bound RNA in a similar manner as did analogous DHBV peptides. The HBV T3 motif could partially substitute for DHBV T3 during RNA binding and DNA priming by DHBV P, whereas replacing RT1 supported substantial RNA binding but not priming. Substituting both the HBV T3 and RT1 motifs restored near wild-type levels of RNA binding but supported very little priming. Alanine-scanning mutations to the HBV T3 and RT1 motifs blocked HBV ε RNA binding in vitro and pgRNA encapsidation in cells. These data indicate that both the HBV T3 and RT1 motifs contain sequences essential for HBV ε RNA binding and encapsidation of the RNA pre-genome, which is similar to their functions in DHBV. Small molecules that bind to T3 and/or RT1 would therefore inhibit encapsidation of the viral RNA and block genomic replication. Such drugs would target a novel viral function and would be good candidates for use in combination with the nucleoside analogs to improve efficacy of antiviral therapy.

Keywords: Hepatitis B virus, DNA priming, encapsidation, RNA binding

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a hepatotropic DNA virus that replicates by reverse transcription (1). It chronically infects >350 million people and kills 0.6-1.2 million patients annually (2-5). Anti-HBV therapy primarily employs nucleos(t)ide analogs that suppress viral replication by 4-5 log10 in 70-90% of patients, often to below the clinical detection limit (6-8). However, treatment eradicates HBV as measured by loss of viral surface antigens in serum in only 3-6% of patients even after years of therapy (6-9), so more effective drugs are urgently needed. Animal hepadnaviruses exist, including the Duck Hepatitis B Virus (DHBV) that is a common model for HBV.

Hepadnaviral reverse transcription (1, 10, 11) occurs within capsid particles in the cytoplasm and is catalyzed by the viral reverse transcriptase (“polymerase”, P). Reverse transcription begins after binding of P to the ε stem-loop on the viral pregenomic RNA (pgRNA) (12-15). This binding requires active participation of the HSP90 class of chaperones that are constitutively associated with P (16-19). P:ε binding triggers encapsidation of both P and the pgRNA into viral capsids (13, 20), where DNA synthesis is primed by a tyrosine residue in the amino‐terminal domain of P using ε as a template (21-24). This results in covalent attachment of the viral DNA to P. Mature intracellular capsids can then either be enveloped and secreted from cells as virions, or they can be transported to the nucleus to replenish the nuclear form of the viral genome called the covalently closed circular DNA (25-27).

P has four domains (28, 29). The terminal protein domain contains the tyrosine that primes DNA synthesis, the spacer domain links the terminal protein domain to the rest of P, the reverse transcriptase domain contains the DNA polymerase active site, and the ribonuclease H (RNAseH) domain degrades the pgRNA during reverse transcription. Complementation studies with fragments of HBV P imply that there are multiple contacts between the terminal protein and the reverse transcriptase/RNAseH domains (23, 30, 31). RNA binding studies with truncated HBV and DHBV P derivatives revealed that sequences from both the terminal protein and reverse transcriptase domains are needed for P to bind RNA and subsequently prime DNA synthesis (12, 17, 31-33). Support for a role for both the terminal protein and reverse transcriptase domains in RNA binding also comes from mutagenesis of DHBV P (34, 35). Similarly, studies with hemin and carbonyl J derivatives directly implicate sequences in both the terminal protein and reverse transcriptase domains as being involved in RNA binding (36, 37).

We previously identified the T3 motif (aa 176-183) in the terminal protein domain and the RT1 motif (aa 385-415) in the reverse transcriptase domain of DHBV P as being essential for P:ε binding (Fig. 1a – c) (38-40). Synthetic peptides containing T3 and RT1 sequences bound RNA, and mutating DHBV T3 and RT1 altered accessibility of the terminal protein domain to monoclonal antibodies, changed its sensitivity to proteolysis, inhibited RNA binding by a truncated version of P [miniRT2; (41)], blocked encapsidation of P, and eliminated viral DNA synthesis. Subsequently, Stahl, et al. (35) found that the DHBV T3 motif is buried within the protein structure but is transiently exposed by the chaperones that are complexed to P. They also found that mutations within T3 disrupted RNA binding without globally disrupting folding of P.

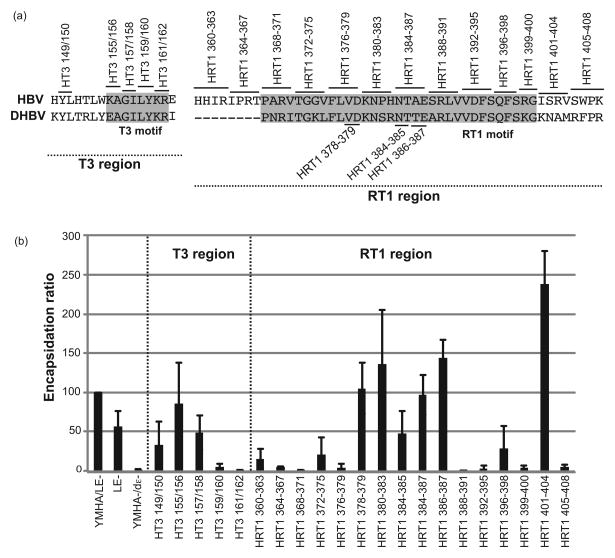

Figure 1. HBV T3 and RT1 sequences bind nucleic acids non-specifically.

(a) The HBV polymerase. The terminal protein (TP), spacer, reverse transcriptase (RT), and RNAseH domains and the T3 and RT1 motifs are shown. (b) The T3 motif. Sequences of P flanking the T3 motif are shown for avian (DHBV through RGHBV) and mammalian (WHV through HBV) hepadnaviruses. The T3 motif is shaded. (c) The RT1 motif. The definition of this motif has been expanded by two residues at the N-terminus relative to the numbering used in Badtke et al. (40). (d) T3 and RT1 peptide RNA binding assay. HBV and DHBV T3 and RT1 peptides were bound to a nitrocellulose filter in a slot-blot apparatus, 32P-labeled HBV or DHBV ε RNA was passed through the filter in 3 concentrations (H, M, L), the filter was washed, and bound RNA was detected by autoradiography. DHBV and HBV T3-scramble are negative control peptides in which the sequences have been scrambled.

These observations with DHBV P led us to hypothesize that T3 and RT1 form an interdomain RNA binding site (40). We proposed that the T3 and RT1 motifs initially bind RNA non-specifically, and that these non-specific interactions are essential for subsequent specific binding between P and the pgRNA. The roles for the T3 and RT1 motifs were hypothesized to be conserved among the hepadnaviruses due to their high homology between DHBV and HBV. Here, we tested whether the HBV T3 and RT1 motifs participate in RNA binding and pgRNA encapsidation as predicted from studies with DHBV.

Materials and Methods

Viruses and plasmids

All plasmids are listed in Table 1. pCMV-HBV-LE–II (LE–II) is an HBV pgRNA expression vector containing 1.2 copies of the HBV(adw2) genome downstream of the CMV promoter in pBS– (Promega). It carries mutations that ablate expression of the surface proteins to prevent expression of infectious HBV. YMHA/LE- is pCMV-HBV-LE–II in which the YMDD motif of the DNA polymerase active site is mutated to prevent conversion of the pgRNA into DNA. YMHA-/dε- is a derivative of YMHA/LE- in which part of ε is deleted to block encapsidation. pMiniRT2 is a bacterial expression vector encoding DHBV P residues 74-245 and 352-575 in pRsetB (Invitrogen). HT3, HRT1, HT3/HRT1, HRT1b, HT3/HRT1b, HT3/HRT1c and HT3/HRT1d are derivatives of pminiRT2 in which the DHBV T3 and/or RT1 motifs with or without their immediate flanking regions are replaced with the corresponding HBV sequences. Clones HT3-155/156A to HRT1-405-408A carry paired or quadruple alanine-scanning mutations across the T3 and RT1 regions in pcDNA-3FHP (24), which expresses an N-terminally 3xFLAG-tagged HBV P gene (serotype ayw) under the CMV promoter in pcDNA3 (Invitrogen). This P allele lacks residues 17 and 18 in the terminal protein domain and residues 186-196 in the spacer domain relative to the P protein used for the other experiments. The T3 motif and its flanking sequences are identical in the two proteins, and the RT1 motif has only one variation (A369S) in the ayw protein relative to P expressed by pCMV-HBV-LE-II. For consistency, mutations in pcDNA-3FHP are numbered relative to pCMV-HBV-LE-II. HT3-149/150 to HRT1-405-408 carry paired or quadruple alanine-scanning mutations across the T3 and RT1 regions in YMHA/LE-. Genbank accession numbers for the sequences in Fig. 1 are DQ195079 (Duck hepatitis B virus, DHBV), CAC80820 (Stork hepatitis virus, SHV), AAA45738 (Heron hepatitis virus, HHV), AAA45748 (Ross' goose hepatitis virus, RGHV), AAA46767 (Woodchuck hepatitis virus, WHV), P03161 (Ground squirrel hepatitis virus, GSHV), AAC16908 (Woolly monkey hepatitis virus, WMHV) and AM282986 (HBV, adw2 clone). The Genbank number for the serotype ayw P sequences in the 3xFLAG-tagged HBV P gene is V01460.1.

Table 1. Plasmids employed.

| Names | Description |

|---|---|

| LE-II | HBV full-length expression vector containing 1.2 copies of HBV genome under the CMV promoter with stop codons in surface protein genes L and S that together block production of all three surface antigens. |

| YMHA/LE- | Mutating enzymatic active site YMDD to YMHA in the LE-II background, which is a parental plasmid for the mutants used in the encapsidation study. |

| YMHA-/dε | Encapsidation-deficient YMHA/LE- derivative with the left lower half of ε knocked out. |

| MiniRT2 | DHBV P bacterial expression vector that encodes a truncation of P which contains aa 74-245 and 352-575 under pCDNA 3.1 background. |

| HT3 | MiniRT2 with T172H, R173T, Y175W, E176K mutations in DHBV P (mutated positions indicated with the DHBV residue numbers). |

| HRT1 | MiniRT2 with N384A, I386V, K389G, L390V, S397P, R398H, T401A, A403S and K414R mutations in DHBV P (mutated positions indicated with the DHBV residue numbers). |

| HT3/HRT1 | MiniRT2 with HT3 and HRT1 mutations in DHBV P. |

| HRT1b | MiniRT2 with N384A, I386V, K389G, L390V, T401A, A403S and K414R mutations in DHBV P (mutated positions indicated with the DHBV residue numbers). |

| HT3/HRT1b | MiniRT2 with HT3 and HRT1b mutations in DHBV P. |

| HT3/HRT1c | MiniRT2 with HT3 and HRT1 mutations, plus R377I,G378R,N379I,T380P,S381R,W382T mutations in DHBV P (mutated positions indicated with the DHBV residue numbers). |

| HT3/HRT1d | MiniRT2 with HT3 and HRT1 mutations, plus K416I, N417S, A418R, M419V, R420S, F421W mutations in DHBV P (mutated positions indicated with the DHBV residue numbers). |

| pcDNA-3FHP | 3×FLAG-tagged HBV P under the human cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter in pcDNA3. |

| HT3-155/156A | pcDNA-3FHP with K155A, A156G mutations in HBV P. |

| HT3-157/158A | pcDNA-3FHP with G157A, I158A mutations in HBV P. |

| HT3-159/160A | pcDNA-3FHP with L159A, Y160A mutations in HBV P. |

| HT3-161/162A | pcDNA-3FHP with K161A,R162A mutations in HBV P. |

| HRT1-364-367A | pcDNA-3FHP with I364A/P365A/R366A/T367A mutations in HBV P. |

| HRT1-368-371A | pcDNA-3FHP with P368A/S369G/R370A/V371A mutations in HBV P. |

| HRT1-376-379A | pcDNA-3FHP with F376A/L377A/V378A/D379A mutations in HBV P. |

| HRT1-378-379A | pcDNA-3FHP with V378A, D379A mutations in HBV P. |

| HRT1-384-385A | pcDNA-3FHP with N384A, T385A mutations in HBV P. |

| HRT1-386-387A | pcDNA-3FHP with A386G, E387A mutations in HBV P. |

| HRT1-392-395A | pcDNA-3FHP with V392A/D393A/F394A/S395A mutations in HBV P. |

| HRT1-399-400A | pcDNA-3FHP with R399A, G400A mutations in HBV P. |

| HRT1-405-408A | pcDNA-3FHP with S405A/W406A/P407A/K408A mutations in HBV P. |

| HT3-149/150 | YMHA/LE- with Y149A, L150A mutations in HBV P. |

| HT3-155/156 | YMHA/LE- with K155A, A156G mutations in HBV P. |

| HT3-157/158 | YMHA/LE- with G157A, I158A mutations in HBV P. |

| HT3-159/160 | YMHA/LE- with L159A, Y160A mutations in HBV P. |

| HT3-161/162 | YMHA/LE- with K161A, R162A mutations in HBV P. |

| HRT1-360-363 | YMHA/LE- with H360A,H361A,I362A and R363A mutations in HBV P. |

| HRT1-364-367 | YMHA/LE- with I364A,P365A,R366A and T367A mutations in HBV P. |

| HRT1-368-371 | YMHA/LE- with P368A,A369G,R370A and V371A mutations in HBV P. |

| HRT1-372-375 | YMHA/LE- with T372A,G373A,G374A and V375A mutations in HBV P. |

| HRT1-376-379 | YMHA/LE- with F376A,L377A,V378A and D379A mutations in HBV P. |

| HRT1-378-379 | YMHA/LE- with V378A and D379A mutations in HBV P. |

| HRT1-380-383 | YMHA/LE- with K380A,N381A,P382A and H383A mutations in HBV P. |

| HRT1-384-387 | YMHA/LE- with N384A,T385A,A386G and E387A mutations in HBV P. |

| HRT1-384-385 | YMHA/LE- with N384A and T385A mutations in HBV P. |

| HRT1-386-387 | YMHA/LE- with A386G and E387A mutations in HBV P. |

| HRT1-388-391 | YMHA/LE- with S388A,R389A,L390A and V391A mutations in HBV P. |

| HRT1-392-395 | YMHA/LE- with V392A,D393A,F394A and S395A mutations in HBV P. |

| HRT1-396-398 | YMHA/LE- with Q396A,F397A, and S398A mutations in HBV P. |

| HRT1-399-400 | YMHA/LE- with R399A and G400A mutations in HBV P. |

| HRT1-401-404 | YMHA/LE- with I401A,S402A,R405A and V406A mutations in HBV P. |

| HRT1-405-408 | YMHA/LE- with S405A,W406A,P407A and K408A mutations in HBV P. |

Cell culture, transfection and isolation of intracellular HBV cores

Huh7 human hepatoma cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F12 with 10% fetal bovine serum. Transfections employed FuGENE (Roche Diagnostics) or LT1 (Mirus) and according to the manufacturer's instructions. Four days post-transfection, cells were lysed in core particle preparation lysis buffer [CPLB; 10 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 1 mM EDTA, 0.25% NP40, 50 mM NaCl, 8% sucrose], and the lysates were treated with micrococcal nuclease. 20% of the lysate was used for total RNA isolation and 80% was used for core particle isolation by sedimentation through a sucrose cushion as described (42). 3xFLAG-tagged P derivatives for the ε RNA binding assays were isolated from transfected 293T cells as described (24).

Chimeric miniRT2 expression and purification

MiniRT2 chimeric constructs containing a hexa-histidine tag on the N-terminus were expressed in BL21(DE3)-codon+ E. coli cells and purified by nickel-affinity chromatography as described (43).

Synthetic peptides

Synthetic peptides were purchased from Genscript. The peptides were: Wild-type HBV T3 (HYLHTLWKAGILYKRETTSRSASFCGSP), HBV T3-scramble (RSYWFYCLAARLKGTSTEHLTIPGKHS), HBV RT1 (RTPARVTGGVFLVDKNPHNTAESRLVVDFSQFSRGISR), wild-type DHBV T3 (KYFNRLYEAGILYKRISKHLVTFK), and DHBV T3-scramble (SKLRYFTYFLHNKLIRGIVKAKYE). The T3 and RT1 motifs are underlined.

In vitro priming assay

200 ng purified miniRT2 or its derivatives, 10 μCi [α32P]dGTP (3000 Ci/mmole, GE Healthcare), 0.25 μg ε and 0.5% NP40 were incubated at 30° for 2 hours in TMnNK [20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 1mM MnCl2, 15 mM NaCl, 20 mM KCl, 2 mM DTT], the samples were resolved by SDS polyacrylamide electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and the signal was detected by autoradiography.

RNA binding assays

MiniRT2 proteins or peptides (0.2 μg) were dissolved in TMnNK plus 0.5% NP40, applied to a nitrocellulose filter, and the filter was washed with TMnNK plus 0.5% NP40. 32P-radiolabeled HBV and DHBV ε RNAs dissolved in TMnNK were passed through the filter, the filter was washed twice, and retained ε was detected by autoradiography.

Purified P from 293T cells was detected by western blotting using the M2 antibody (Sigma). The FLAG lysis buffer was removed from aliquots of P-bound M2 beads, and then aliquots of beads were incubated with 0.5 μg 32P-labeled ε RNAs in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer [50 mM Tris (pH 7.0), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.05% NP-40] with 1× complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), 2 mM DTT, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and 1 U/μl RNasin Plus RNase inhibitor (Promega) (24). After 3 hours incubation at room temperature, unbound materials were removed and the beads were washed in RIPA buffer containing 2 mM DTT, 28 μM E-64, 1 mM PMSF and 5 μg/mL leupeptin and 10 U RNasin Plus per ml. Bound materials were eluted by boiling and resolved by SDS-PAGE. The gel was dried and 32P-labeled RNA was quantified via phosphorimaging.

HBV encapsidation assay

Total cytoplasmic RNA and encapsidated pgRNA were isolated from Huh7 cell lysates or HBV core particle preparations employing Tri-Reagent (Molecular Research Center) and were treated with DNAseI to remove contaminating DNA. cDNA was synthesized using random hexamer primers and MultiScribe™ Reverse Transcriptase (Applied Biosystems). HBV cDNA was quantified by quantitative PCR targeting the pgRNA upstream of the start sites for the surface antigen genes employing the Applied Biosystems 7500 Sequence Detection System. Amplification was performed in 25 μL of TaqMan universal Mastermix (Applied Biosystems) containing 5 μL cDNA, 0.2 μM sense primer (5′- GCCTCGCAGACGCAGATC -3′, HBV positions 580 to 597) and antisense (5′- CTAACATTGAGATTCCCGAGATTG -3′, positions 623 to 646) primers and 0.1 μM probe (5′-FAM T CAATCGCCGCGTCGCAGAAGA -TAMRA-3′, positions 599-619). PCR conditions were: 2 minutes at 50°C and 10 minutes at 95°C followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 60 seconds. cDNA derived from in vitro transcribed HBV polymerase RNA was used for the standard curve.

Results

HBV T3 and RT1 sequences bind RNA non-specifically

Synthetic peptides containing DHBV T3 and RT1 sequences non-specifically bind RNA (40). Therefore, we asked whether homologous HBV peptides also bind RNA and if they have specificity for HBV ε. HBV wild-type T3, T3-scramble negative control, and wild-type RT1 synthetic peptides were bound to a nitrocellulose filter in a slot-blot apparatus; DHBV T3 wild-type and scrambled peptides were included as controls. 32P-labeled DHBV or HBV ε RNA was passed through the filter at 1.5, 0.9 and 0.45 μg/mL for HBV ε and 0.8, 0.48, and 0.24 μg/mL for DHBV ε, the filter was washed, and bound RNA was detected by autoradiography. As previously observed, the wild-type DHBV T3 peptide bound both HBV and DHBV ε RNAs and DHBV T3-scramble did not bind RNA (Fig. 1d). HBV T3 and RT1 peptides also bound RNA proportional to the amount of RNA passed through the filter, and the HBV T3-scramble peptide did not. RNA binding was non-specific because the peptides bound both HBV ε and DHBV ε RNAs (Fig. 1d) and a non-ε RNA called DRF+ (DHBV nt 2401-2605) that does not bind specifically to the full-length DHBV P (data not shown). Therefore, peptides containing HBV T3 or RT1 sequences bind RNA non-specifically.

HBV T3 and RT1 motifs can partially substitute for the corresponding DHBV sequences

We hypothesized that the T3 and RT1 regions would be interchangeable to some extent between DHBV and HBV due to their high sequence homology. Therefore, we created chimeric DHBV miniRT2 derivatives containing the HBV T3 motif and its immediate flanking sequences and/or the HBV RT1 motifs and evaluated their ability to bind RNA and prime DNA synthesis. MiniRT2 is a truncation derivative of DHBV P (Fig. 2a) that can specifically prime DNA synthesis in the presence of DHBV ε and can be readily purified from E. coli. Therefore, we created chimeric DHBV miniRT2 proteins containing sequences corresponding to the HBV T3 and RT1 motifs (HT3, HRT1, HT3/HRT1, HRT1b, HT3/HRT1b, HT3/HRT1c and HT3/RT1d; Table 1 and Fig. 2b); the immediate flanking sequences were included in the T3 chimeras because the HBV and DHBV T3 motifs are nearly identical.

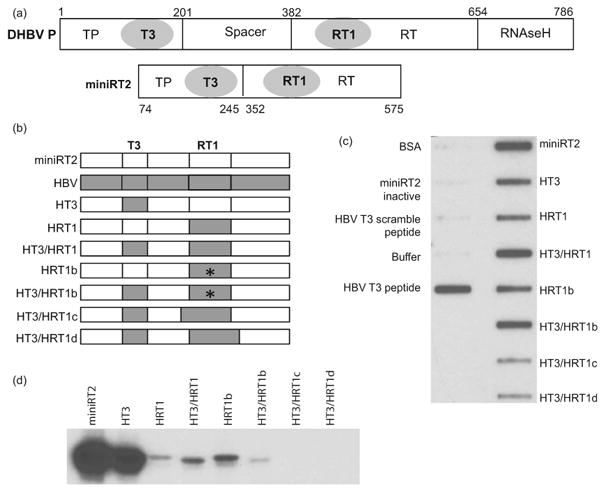

Figure 2. Function of the HBV T3 and RT1 motifs in DHBV P.

(a) The DHBV polymerase and its miniRT2 truncation derivative. The terminal protein (TP), spacer, reverse transcriptase (RT), and RNAseH domains are shown. The amino acid positions for the domain and truncation boundaries are for DHBV P. (b) Structure of chimeric DHBV mRT2 derivatives carrying HBV T3 and/or RT1 motifs. * denotes the P382S/H383R mutations in the RT1 region. (c) In vitro RNA binding assay. Binding of purified miniRT2 derivatives to 32P-labeled DRF+ RNA was determined using a filter-binding assay analogous to the peptide:RNA binding assay in Fig. 1. (d) In vitro DNA priming assay. Equal amounts of miniRT2 chimeric constructs were incubated with DHBV ε and [α32P]dGTP and the products were resolved by SDS-PAGE. DNA priming was detected as covalent attachment of 32P to the proteins.

We first measured the effects of substituting the DHBV T3 and/or RT1 sequences on RNA binding. pMiniRT2 chimeric proteins containing an N-terminal hexa-histidine tag were expressed in E. coli and purified by nickel-affinity chromatography. Equal amounts of the recombinant proteins were bound to a filter and binding to 32P-labeled DRF+ RNA was determined using a filter-binding assay. None of the negative controls [bovine serum albumin, GST-tagged miniRT2 that is enzymatically active in solution but cannot bind RNA in this assay due to interference of the GST tag with the RNA binding motifs when the enzyme is bound to the filter (41), HBV T3 scrambled peptide, or buffer] bound DHBV ε RNA, whereas binding was readily detected when the HBV T3 peptide or wild-type his-tagged miniRT2 were employed as positive controls. Replacing either the DHBV T3 or RT1 motifs with the corresponding HBV sequences in constructs HT3 and HRT1 reduced RNA binding by about half compared to wild-type miniRT2. Substituting both the HBV T3 and RT motifs in the construct HT3/HRT1 restored RNA binding by the chimeric protein to wild-type levels. Similar results were obtained when DHBV or HBV ε RNAs were employed (data not shown).

To further characterize the RT1 motif, we tested whether a pair of non-conserved amino acids in the middle of RT1 (S397/R398 in DHBV vs. P382/H383 in HBV) may contribute to the reduced RNA binding in the HRT1 chimera, we reverted these residues in HRT1 to the DHBV sequence in construct HRT1b. This reversion had no effect on RNA binding by chimeric proteins containing just HBV RT1 or HBV T3 and RT1 motifs (Fig. 2c). We also asked whether additional sequences may contribute to HBV RT1 function by extending the HBV sequences transferred to miniRT2 by six amino acids in the N- and C-terminal directions in constructs HT3/HRT1c and HRT3/HRT1d (Fig. 2b). This nearly ablated the non-specific RNA binding measured by this assay even though HT3 was included in both mutants (Fig. 2c and data not shown).

We next asked whether the HBV T3 and/or RT1 motifs could substitute for their DHBV homologs during DNA priming. MiniRT2 and its derivatives were incubated with DHBV ε and [α32P]dGTP and the products were resolved by SDS-PAGE. In this assay, DNA priming is detected as covalent attachment of [32P]dGMP to miniRT2. The HBV T3 motif substituted well for DHBV T3, whereas the HBV RT1 replacement nearly eliminated DNA priming (Fig. 2d). Substitution of both the HBV T3 and RT1 motifs in the HT3/HRT1 construct modestly increased priming, as did combining the HRT1b motif carrying the reversion mutations with the HBV T3 motif. As expected from their low ability to bind RNA, priming was not detected with mutants HT3/HRT1c and HT3/HRT1d. Therefore, the HBV and DHBV T3 and RT1 motifs are similar enough that chimeric enzymes retained RNA binding activity, but complementation was much less efficient in the more complex priming reaction.

Effect of the HBV T3 and RT1 motifs on RNA binding by full-length P

The effect of mutating the HBV T3 and RT1 motifs and their immediate flanking regions on RNA binding by the full-length protein was evaluated using 3xFLAG-tagged HBV P expressed in 293T cells and purified by anti-FLAG immunoprecipitation. 32P-labeled wild-type HBV ε and a mutant HBV ε (Hε-dB) that cannot bind to P were incubated with P derivatives still attached to the immunoprecipitation beads. The beads were washed, HBV P and bound ε RNAs were resolved by SDS-PAGE, P was detected by western blotting using anti-FLAG antibodies (Fig. 3a), and retained RNAs were quantified by phosphorimaging (Fig. 3b).

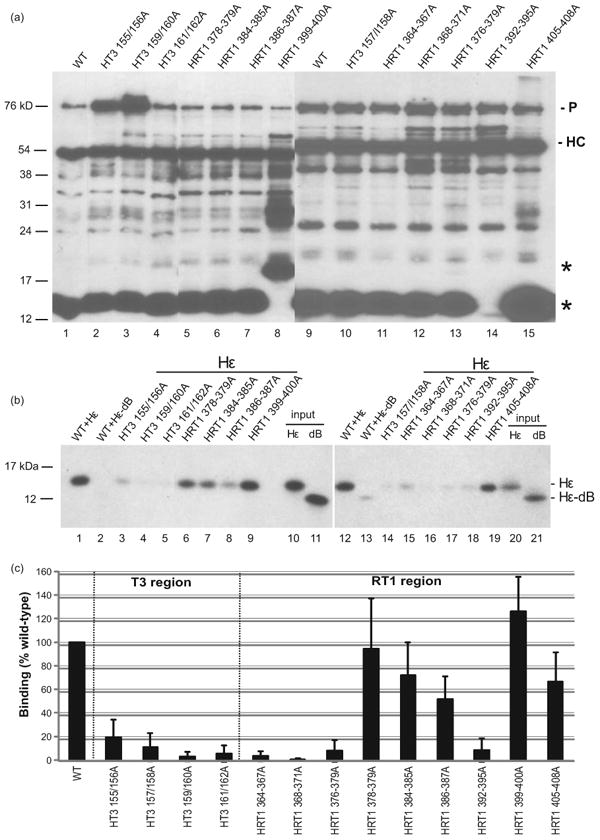

Figure 3. In vitro RNA binding activity of full-length HBV with mutant T3 and RT1 motifs.

(a) Accumulation of HBV P mutants. HBV P derivatives were expressed in transfected 293T cells, immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibodies, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and detected by western blotting using the M2 anti-FLAG antibody; the exposure of the left gel was shorter to limit saturation of the more intense bands. The position of HBV P (P) and the antibody heavy chain (HC) are indicated. * denotes the position of an N-terminal fragment of the 3xFLAG-tagged wild-type P. (b) The immunoaffinity-purified HBV P derivatives were incubated with 32P-labeled wild-type Hε or mutant Hε-dB RNA and co-precipitated products were resolved by SDS–PAGE. Input representing 0.5% of the indicated ε RNA added to each binding reaction mixture is in lanes 10, 11, 20, and 21. (c) Bound 32P-labeled ε RNA signals were quantified via phosphorimaging and compared to the binding of wild-type P to Hε RNA. The data represent the mean ± one standard deviation from at least three independent experiments.

Similar levels of the full-length P proteins were recovered in most cases, but HT3-155/156A and HT3-159/160A accumulated to higher levels in one assay (Fig. 3a). Western blots also revealed a prominent amino-terminal fragment of P that contained part of the terminal protein domain (* in Fig. 3a). This fragment from HRT1-399-400A migrated more slowly than the wild-type fragment, and it was absent for HRT1-392-395A (Fig. 3a). This fragment does not contain the reverse transcriptase domain where the mutations are located, so these mutations appear to have altered recognition of P by cellular proteases.

Purified P specifically associated with ε but not with the negative control mutant ε-dB (Fig. 3b). The HBV T3 motif mutants HT3-155/156A, HT3-157/158A, HT3-159/160A and HT3-161/162A suppressed P:ε binding to <20% relative to the wild-type enzyme (Figs. 3b and 3c). Mutations in the RT1 motif also altered RNA binding (Fig. 3). HRT1-364-367A, HRT1-368-371A, HRT-376-379A, and HRT1-392-395A reduced RNA binding to <20% compared to wild-type. Mutants HRT1-384-385A, HRT1-386-387A, and HRT1-405-408A had modest effects on RNA binding (reduced to 50-70% of wild-type). Mutants HRT1-378-379A and HRT1-399-400A either had no effect on binding or moderately increased it. Therefore, both the HBV T3 and RT1 motifs modulate RNA binding by P, and the effect of mutating the T3 region on RNA binding is overall greater than mutating RT1.

Mutating HBV T3 and RT1 affects encapsidation of the pgRNA

The effects of mutating the HBV T3 and RT1 motifs on pgRNA encapsidation were measured by introducing paired or quadruple alanine-scanning mutations to the T3 and RT1 regions in the HBV pgRNA expression vector pCMV-HBV(YMHA/LE-) (Fig. 4a). Expression of the pgRNA in cells leads to authentic HBV reverse transcription because it is both the template for reverse transcription and the mRNA for P and the capsid protein. The pCMV-HBV(YMHA/LE-) vector contains mutations to the YMDD motif in the DNA polymerase active site that ablate its activity to permit measurement of encapsidation without some of the pgRNA being converted into DNA.

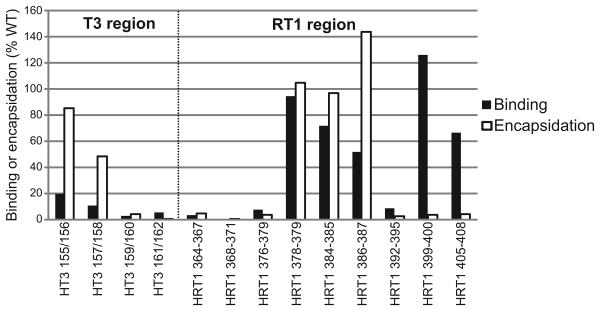

Figure 4. The HBV T3 and RT1 motifs contain sequences essential for encapsidation.

(a) Alignment of amino acids sequence from the DHBV3 and HBV T3 and RT1 regions; shaded regions represent the T3 and RT1 motifs. Alanine-scanning mutations were introduced at the indicated positions in the HBV T3 and RT1 motifs in context of the viral genome. (b) Encapsidation assay. Huh7 cells were transfected with the HBV genomic expression vectors, HBV core particles were isolated, total cytoplasmic RNA and encapsidated RNAs were isolated, and RNA levels were measured by quantitative TaqMan PCR. The encapsidation ratios for all mutants were normalized to the ratio observed with the HBV(YMHA/LE-) control as determined in the same assay. The data are represented as the average ± one standard deviation from three to five independent experiments.

Wild-type and mutant HBV DNAs were transfected into Huh7 cells and cell lysates were prepared four days post-transfection. Total RNA was isolated from 20% of each lysate, capsid particles were isolated from the remaining lysate by sedimentation through a sucrose cushion (44), and encapsidated RNA was isolated from the pellet. cDNA was synthesized from the RNAs using random primers, and HBV cDNAs were quantified by TaqMan PCR. The encapsidation ratio was defined as (encapsidated pgRNA/total pgRNA)×100; ratios were normalized to the wild-type genome (YMHA/LE-) assessed in the same experiment.

Mutating the HBV T3 motif at residues 149/150, 155/156 and 157/158 modestly reduced encapsidation to 48-85% of wild-type, whereas mutating residues 159/160 and 161/162 nearly ablated encapsidation (Fig. 4b). Eleven of the 16 sets of mutations to the RT1 sequences suppressed encapsidation to <50% of wild-type (mutants 360-363, 364-367, 368-371, 372-375, 376-379, 384-387, 388-391, 392-395, 396-398, 399-400, and 405-408). Mutating residues 378-379, 380-383, 384-385, 386-387, and 401-404 had no effect on encapsidation or modestly increased encapsidation (Fig. 4b). These effects were due to encapsidation defects rather than pgRNA stability issues because the pgRNA is the mRNA for both proteins required for encapsidation (the capsid and P proteins), and hence stability effects are eliminated by normalizing to total pgRNA levels. Furthermore, ε is the only cis-acting signal required for HBV encapsidation (45), so modulation of encapsidation by the mutations through altering cis-acting RNA signals is highly unlikely. Therefore, sequences within both the HBV T3 and RT1 motifs are important for pgRNA encapsidation.

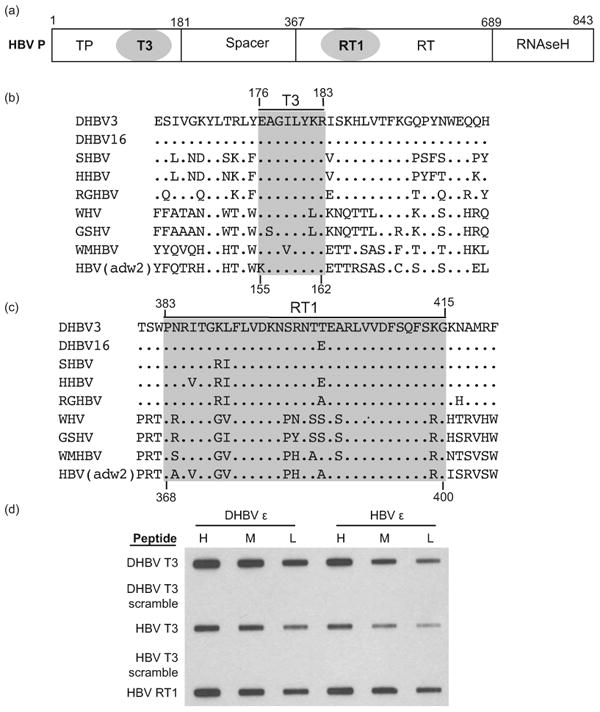

Comparison of RNA binding and encapsidation

RNA binding is a prerequisite for encapsidation, so we compared the effect of mutating HBV T3 and RT1 on RNA binding in vitro and encapsidation in vivo (Fig. 5). Data for 11 of the 13 mutants were consistent with RNA binding being a necessary but not sufficient step for encapsidation. Mutants with lesions at positions 159/160, 161/162, 364/367, 368/371, 376-379, and 392/395 reduced both RNA binding and encapsidation, consistent with an RNA binding deficiency causing the encapsidation defect. Mutants with alterations at positions 399/400 and 405/408 retained robust binding but had severely impaired encapsidation efficiencies, consistent with the mutations affecting a post-binding step in encapsidation. Mutations to positions 378/379, 384/385, and 386/387 retained substantial activity in both RNA binding and encapsidation. Only mutants 155/156 and 157/158 in T3 were discordant; these mutants bound RNA poorly but retained substantial encapsidation activity.

Figure 5. Comparison of the effect of mutating HBV T3 and RT1 on RNA binding in vitro and encapsidation in vivo.

All values are normalized to binding to wild-type HBV ε or encapsidation by wild-type HBV P.

Discussion

Previous studies into the RNA binding mechanism by DHBV P by us and others (12, 17, 38, 40, 42, 44, 46) led us to propose a complex model for RNA binding (40). In this model, P initially adopts a closed conformation in complex with cellular chaperones. The chaperones transiently open the complex, exposing the T3 and RT1 motifs which together form the primary RNA binding site. RNA binding is proposed to proceed through two stages, with an initial non-specific step being followed by a conformation change in P that forms the stable P:ε complex needed to trigger both DNA priming and encapsidation. Here, we extended these studies from DHBV to the human pathogen HBV. Four observations were made: 1) HBV T3 and RT1 peptides could bind RNA (Fig. 1); 2) HBV T3 and RT1 motifs could substitute for the DHBV elements in RNA binding and to a much lesser extent in DNA priming in a chimeric DHBV:HBV minimal polymerase construct (Fig. 2); 3) HBV T3 and RT1 elements both contribute to RNA binding and encapsidation in context of the full-length enzyme (Figs. 3 and 4); 4) The phenotypes of a panel of HBV T3 and RT1 mutants are overall consistent with their hypothesized roles in RNA binding and encapsidation (Fig. 5).

Two technical considerations may affect these results. First, the HBV polymerase accumulates to low levels in cells and cannot be routinely detected without epitope tagging that may change its properties (47). This precludes normalizing the encapsidation data for possible differences in accumulation of the mutant P enzymes. However, most mutants did not show severe defects in accumulation when tested in 3xFLAG-tagged P (Fig. 3a). Second, the amino-terminal fragment of P that accumulates in cells was not present for HRT1-392-395A (Fig. 3a, lane 14), and its mobility was retarded for HRT1-399-400A (Fig. 3a). These mutations to RT1 presumably altered folding of P, changing the exposure of protease cleavage sites in the N-terminal domain of P. However accumulation and mobility of the full-length enzyme was unaffected by these mutations, and the HRT1-399-400 mutant retained ε-binding activity, indicating that global misfolding is unlikely.

Mutants 155/156 and 157/158 in the T3 motif retained only low levels of activity in the in vitro binding assay yet could support substantial levels of encapsidation (Fig. 5). At least three causes can be envisioned for this discrepancy. First, the mutant 155/156 mutant occasionally accumulated to unusually high levels (Fig. 3A), raising the possibility that aberrant folding may have reduced its RNA binding efficiency. Second, the mutations may have reduced the stability of the P:ε complexes enough to cause their disassociation during the lengthy co-precipitation assay but not enough to prevent the transient complexes from triggering encapsidation in cells. Finally, the mutations may have simultaneously reduced RNA binding and increased the specific efficiency of RNA encapsidation, resulting in encapsidation of a higher proportion of the P molecules that managed to bind ε.

These studies provide strong support for the hypotheses that the T3 and RT1 motifs are involved in both RNA binding and encapsidation in both HBV and DHBV (34-38, 40). In both viruses the T3 and RT1 elements contribute to RNA binding by synthetic peptides, purified miniRT2 derivatives, and the full-length enzyme [(40) and Figs. 1-3]. Furthermore, the data demonstrate a role for the T3 and RT1 motifs in steps beyond RNA binding for both DHBV and HBV. The impact of mutating the DHBV T3 and/or RT1 motifs on DNA priming has been measured (34, 35, 40), and here we demonstrate a role for the HBV T3 and RT1 motifs during encapsidation (Fig. 4). These studies also begin to dissect the relative roles of the two elements. All four T3 mutations assessed for RNA binding in vitro were severely impaired, whereas most of the RT1 mutants had less severe effects on binding (Fig. 3). In contrast, only three of the five T3 mutants examined reduced encapsidation by >50%, whereas 11 of 16 RT1 mutants had over a 2-fold defect in encapsidation and the defects from mutating RT1 were usually more severe. This implies that the T3 element may function primarily in RNA binding, whereas RT1 is clearly important for both RNA binding and encapsidation. A role for the RT1 motif beyond simply binding RNA is also supported by data with the chimeric DHBV miniRT2 constructs (Fig. 2). The HBV T3 motif and its immediate flanking sequences could complement both RNA binding and DNA priming to about 50% wild-type levels in the chimeric miniRT2 proteins, whereas the RT1-containing chimeras bound RNA adequately but primed DNA synthesis very poorly.

The complexity of the hepadnaviral RNA binding and encapsidation mechanisms implies that these reactions should be amenable to disruption by inhibitors that bind to T3 and/or RT1 and block RNA binding or disrupt the conformational changes in P that are associated with binding. This would block reverse transcription at a step distinct from all existing anti-HBV drugs. Drugs targeting RNA binding or encapsidation should have a high selective index because the hepadnaviral RNA binding and encapsidation reactions have no known cellular counterparts. Furthermore, neither T3 nor RT1 contain residues in which nucleos(t)ide analog resistance mutations have been found, so drugs targeting the T3:RT1 site would be unlikely to lead to cross-resistance with the nucleos(t)ide analogs. Therefore, antagonists of the T3:RT1 site would be good candidates for use in combination with the nucleos(t)ide analogs, permitting multi-drug inhibition of HBV. Indeed, peptide fragments containing these motifs have recently been shown to block P-ε binding and protein priming in DHBV (33, 40).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. William Wold for scientific and logistical assistance and Dr. Maureen Donlin for technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- DHBV

duck hepatitis B virus

- HBV reverse transcriptase

(P)

- pgRNA

pre-genomic RNA

- ε

HBV's encapsidation signal and origin of replication

- miniRT2

a DHBV P truncation derivative that retains priming activity

Footnotes

Statement of Interests: 1. Authors' declaration of personal interests: None of the authors have a personal interest related to the work reported here.

2. Declaration of funding interests: This work was supported by NIH grants R43AI084232 to F.C. at VirRx, Inc. and R01AI074982 to J.H. at the Pennsylvania State University. S.J. was supported by the training grant “Viruses and Cancer,” T32CA60395.

References

- 1.Seeger C, Zoulim F, Mason WS. Hepadnaviruses. In: Knipe DM, Howley P, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Roizman B, et al., editors. Fields Virology 5. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. pp. 2977–3029. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shepard CW, Simard EP, Finelli L, Fiore AE, Bell BP. Hepatitis B virus infection: epidemiology and vaccination. EpidemiolRev. 2006;28:112–25. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxj009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ganem D, Prince AM. Hepatitis B virus infection--natural history and clinical consequences. NEnglJ Med. 2004;350(11):1118–29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra031087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lavanchy D. Hepatitis B virus epidemiology, disease burden, treatment, and current and emerging prevention and control measures. J Viral Hepat. 2004;11(2):97–107. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2003.00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sorrell MF, Belongia EA, Costa J, Gareen IF, Grem JL, Inadomi JM, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: management of hepatitis B. AnnInternMed. 2009;150(2):104–10. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-2-200901200-00100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Bommel F, De Man RA, Wedemeyer H, Deterding K, Petersen J, Buggisch P, et al. Long-term efficacy of tenofovir monotherapy for hepatitis B virus-monoinfected patients after failure of nucleoside/nucleotide analogues. Hepatology. 2010;51(1):73–80. doi: 10.1002/hep.23246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woo G, Tomlinson G, Nishikawa Y, Kowgier M, Sherman M, Wong DK, et al. Tenofovir and entecavir are the most effective antiviral agents for chronic hepatitis B: a systematic review and Bayesian meta-analyses. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(4):1218–29. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marcellin P, Heathcote EJ, Buti M, Gane E, De Man RA, Krastev Z, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus adefovir dipivoxil for chronic hepatitis B. NEnglJMed. 2008;359(23):2442–55. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wursthorn K, Jung M, Riva A, Goodman ZD, Lopez P, Bao W, et al. Kinetics of hepatitis B surface antigen decline during 3 years of telbivudine treatment in hepatitis B e antigen-positive patients. Hepatology. 2010;52(5):1611–20. doi: 10.1002/hep.23905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Summers J, Mason WS. Replication of the Genome of a Hepatitis B-Like Virus by Reverse Transcription of an RNA Intermediate. Cell. 1982;29:403–15. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90157-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tavis JE, Badtke MP. Hepadnaviral Genomic Replication. In: Cameron CE, G”tte M, Raney KD, editors. Viral Genome Replication. New York: Springer Science+Business Media, LLC; 2009. pp. 129–43. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pollack JR, Ganem D. Site-specific RNA binding by a hepatitis B virus reverse transcriptase initiates two distinct reactions: RNA packaging and DNA synthesis. JVirol. 1994;68:5579–87. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.5579-5587.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirsch RC, Lavine JE, Chang LJ, Varmus HE, Ganem D. Polymerase gene products of hepatitis B viruses are required for genomic RNA packaging as well as for reverse transcription. Nature (London) 1990;344(6266):552–5. doi: 10.1038/344552a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Junker-Niepmann M, Bartenschlager R, Schaller H. A short cis-acting sequence is required for hepatitis B virus pregenome encapsidation and sufficient for packaging of foreign RNA. EMBO J. 1990;9(10):3389–96. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07540.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beck J, Nassal M. Sequence- and Structure-Specific Determinants in the Interaction between the RNA Encapsidation Signal and Reverse Transcriptase of Avian Hepatitis B Viruses. JVirol. 1997;71:4971–80. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.4971-4980.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu J, Seeger C. Hsp90 is required for the activity of a hepatitis b virus reverse transcriptase. ProcNatlAcadSciUSA. 1996;93:1060–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.3.1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu J, Anselmo D. In vitro reconstitution of a functional duck hepatitis b virus reverse transcriptase: posttranslational activation by HSP90. JVirol. 2000;74:11447–55. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.24.11447-11455.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu J, Toft DO, Seeger C. Hepadnavirus assembly and reverse transcription require a multi-component chaperone complex which is incorporated into nucleocapsids. EMBO J. 1997;16:59–68. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu J, Flores D, Toft D, Wang X, Nguyen D. Requirement of heat shock protein 90 for human hepatitis B virus reverse transcriptase function. JVirol. 2004;78(23):13122–31. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.23.13122-13131.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bartenschlager R, Schaller H. Hepadnaviral assembly is initiated by polymerase binding to the encapsidation signal in the viral RNA genome. EMBO Journal. 1992;11:3413–20. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05420.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weber M, Bronsema V, Bartos H, Bosserhoff A, Bartenschlager R, Schaller H. Hepadnavirus P Protein Utilizes a Tyrosine Residue in the TP Domain to Prime Reverse Transcription. JVirol. 1994;68:2994–9. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.2994-2999.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zoulim F, Seeger C. Reverse Transcription in Hepatitis B Viruses is Primed by a Tyrosine Residue of the Polymerase. JVirol. 1994;68:6–13. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.1.6-13.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lanford RE, Notvall L, Lee H, Beams B. Transcomplementation of Nucleotide Priming and Reverse Transcription between Independently Expressed TP and RT Domains of the Hepatitis B Virus Reverse Transcriptase. JVirol. 1997;71:2996–3004. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.2996-3004.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones SA, Boregowda R, Spratt TE, Hu J. In vitro epsilon RNA-dependent protein priming activity of human hepatitis B virus polymerase. J Virol. 2012 May;86(9):5134–50. doi: 10.1128/JVI.07137-11. Epub 2012/03/02. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tuttleman JS, Pourcel C, Summers J. Formation of the pool of covalently closed circular viral DNA in hepadnavirus-infected cells. Cell. 1986;47(3):451–60. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90602-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levrero M, Pollicino T, Petersen J, Belloni L, Raimondo G, Dandri M. Control of cccDNA function in hepatitis B virus infection. JHepatol. 2009;51(3):581–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zoulim F. Antiviral therapy of chronic hepatitis B: can we clear the virus and prevent drug resistance? AntivirChemChemother. 2004;15(6):299–305. doi: 10.1177/095632020401500602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang LJ, Hirsch RC, Ganem D, Varmus HE. Effects of insertional and point mutations on the functions of the duck hepatitis B virus polymerase. JVirol. 1990;64:5553–8. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.11.5553-5558.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Radziwill G, Tucker W, Schaller H. Mutational analysis of the hepatitis B virus P gene product: domain structure and RNase H activity. JVirol. 1990;64(2):613–20. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.2.613-620.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lanford RE, Kim YH, Lee H, Notvall L, Beames B. Mapping of the hepatitis B virus reverse transciptase TP and RT domains by transcomplementation for nucleotide priming and by protein-protein interaction. JVirol. 1999;73:1885–93. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.1885-1893.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beck J, Nassal M. Reconstitution of a functional duck hepatitis B virus replication initiation complex from separate reverse transcriptase domains expressed in Escherichia coli. JVirol. 2001;75(16):7410–9. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.16.7410-7419.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu J, Boyer M. Hepatitis B virus reverse transcriptase and epsilon RNA sequences required for specific interaction in vitro. JVirol. 2006;80(5):2141–50. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.5.2141-2150.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boregowda RK, Adams C, Hu J. TP-RT domain interactions of duck hepatitis B virus reverse transcriptase in cis and in trans during protein-primed initiation of DNA synthesis in vitro. J Virol. 2012 Jun;86(12):6522–36. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00086-12. Epub 2012/04/20. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seeger C, Leber EH, Wiens LK, Hu J. Mutagenesis of a Hepatitis B Virus Reverse Transcriptase Yields Temperature-Sensitive Virus. Virology. 1996;222:430–9. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stahl M, Beck J, Nassal M. Chaperones activate hepadnavirus reverse transcriptase by transiently exposing a C-proximal region in the terminal protein domain that contributes to epsilon RNA binding. JVirol. 2007;81(24):13354–64. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01196-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin L, Hu J. Inhibition of hepadnavirus reverse transcriptase-epsilon RNA interaction by porphyrin compounds. JVirol. 2008;82(5):2305–12. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02147-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang YX, Wen YM, Nassal M. Carbonyl J acid derivatives block protein priming of hepadnaviral P protein and DNA-dependent DNA synthesis activity of hepadnaviral nucleocapsids. J Virol. 2012 Sep;86(18):10079–92. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00816-12. Epub 2012/07/13. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cao F, Badtke MP, Metzger LM, Yao E, Adeyemo B, Gong Y, et al. Identification of an essential molecular contact point on the duck hepatitis B virus reverse transcriptase. JVirol. 2005;79(16):10164–70. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10164-10170.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Badtke MP, Cao F, Tavis JE. Combining genetic and biochemical approaches to identify functional molecular contact points. BiolProcedOnline. 2006;8:77–86. doi: 10.1251/bpo121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Badtke MP, Khan I, Cao F, Hu J, Tavis JE. An interdomain RNA binding site on the hepadnaviral polymerase that is essential for reverse transcription. Virology. 2009;390(1):130–8. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang X, Qian X, Guo HC, Hu J. Heat shock protein 90-independent activation of truncated hepadnavirus reverse transcriptase. JVirol. 2003;77(8):4471–80. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.8.4471-4480.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tavis JE, Massey B, Gong Y. The Duck Hepatitis B Virus Polymerase Is Activated by Its RNA Packaging Signal, Epsilon. JVirol. 1998;72:5789–96. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.5789-5796.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cao F, Donlin MJ, Turner K, Cheng X, Tavis JE. Genetic and biochemical diversity in the HCV NS5B RNA polymerase in the context of interferon alpha plus ribavirin therapy. JViral Hepat. 2011;18:349–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2010.01316.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gong Y, Yao E, Stevens M, Tavis JE. Evidence that the first strand-transfer reaction of duck hepatitis B virus reverse transcription requires the polymerase and that strand transfer is not needed for the switch of the polymerase to the elongation mode of DNA synthesis. JGenVirol. 2000;81:2059–65. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-8-2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hirsch RC, Loeb DD, Pollack JR, Ganem D. cis-Acting Sequences Required for Encapsidation of Duck Hepatitis B Virus Pregenomic RNA. JVirol. 1991;65(6):3309–16. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.6.3309-3316.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stahl M, Retzlaff M, Nassal M, Beck J. Chaperone activation of the hepadnaviral reverse transcriptase for template RNA binding is established by the Hsp70 and stimulated by the Hsp90 system. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(18):6124–36. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cao F, Tavis JE. Detection and characterization of cytoplasmic hepatitis B virus reverse transcriptase. JGenVirol. 2004;85(Pt 11):3353–60. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80297-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]