Abstract

Background

The clinical characteristics of elderly patients with AML differ from those of younger patients, resulting in poorer survival and treatment outcomes. We analyzed retrospectively the clinical data of AML patients 65 years old and above to describe patients' characteristics and treatment patterns, and to define meaningful prognostic factors of survival in the Korean population.

Methods

Basic patients' characteristics, clinical outcomes according to treatments, and prognostic factors associated with survival and treatment intensity were examined in a total of 168 patients diagnosed in 5 institutes between 1996 and 2012 as having AML.

Results

Herein, 84 patients (50.0%) received high-intensity regimens (HIR), 18 (10.7%) received low-intensity regimens (LIR), and 66 (39.3%) received supportive care (SC) only. The median survival of all patients was 4.5 months; and median survival times with HIR, LIR, and SC were 6.8 months, 10.2 months, and 1.6 months, respectively. Median survival times with HIR and LIR were significantly longer than that with SC (P<0.0001 and P=0.006, respectively). Multivariate analysis identified age, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group-performance status (ECOG-PS), hemoglobin (Hb) level, and serum creatinine (Cr) level as statistically significant prognostic factors for survival. In the HIR group, prognostic factors for survival were ECOG-PS, Hb level, and C-reactive protein level.

Conclusion

Even in elderly AML patients, an intensive treatment regimen could be beneficial with careful patient selection. Further prospective studies designed to identify specific prognostic factors are required to establish an optimal treatment strategy for elderly AML patients.

Keywords: Acute myeloid leukemia, Survival, Prognosis, Chemotherapy, Elderly

INTRODUCTION

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is the most common acute leukemia in adults. The median age of patients is 65-70 years of at diagnosis [1]. Intensive treatments such as high-dose chemotherapy and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation are effective in improving the survival of these patients [2]. However, many patients are not eligible for these treatments owing to their advanced age, poor performance, or comorbidity. Furthermore, factors negatively influencing treatment outcomes, including adverse cytogenetic and molecular aberrations, antecedent hematologic disorders, and the incidence of fatal infection or bleeding, are more frequent in old age [3]. As a result, the prognosis of elderly AML patients is very poor even with intensive treatment [3, 4, 5, 6, 7].

For these reasons, studies have been performed to identify optimal patient characteristics and optimal treatment regimens in elderly patients with AML. Specific parameters including clinical manifestations, laboratory values, and molecular and genetic markers have been suggested as prognostic or predictive factors [7].

In this study, we analyzed the clinical characteristics, treatment patterns, and outcomes of elderly AML patients (65 years old and above) treated at 5 Korean healthcare facilities. Prognostic factors were also analyzed to define the relationship among clinical parameters, treatment patterns, and patient survival.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Patients who were at least 65 years old and were diagnosed with AML between 1996 and 2012 were included in this study. Five institutes located in Gyeonggi province and Incheon city, Korea participated in this study, and a total of 168 cases were analyzed. The following clinical parameters were included in the analysis: age, gender, antecedent hematologic disorder, cytogenetic risk group classified according to the Southwest Oncology Group and Medical Research Council (SWOG/MRC) criteria, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (ECOG-PS), Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation-Specific Comorbidity Index (HCT-CI), common blood cell count (CBC) test, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), C-reactive protein (CRP), bone marrow (BM) blast percent, and other laboratory values that have been referred to as prognostic factors in past studies.

Treatment patterns and response criteria

Treatment patterns were divided into 3 groups: high-intensity regimen (HIR), low-intensity regimen (LIR), and supportive care (SC) groups. Treatment for the HIR group consisted of anthracycline, high dose cytarabine and fludarabine; treatment for the LIR group consisted of low dose cytarabine, hypomethylating agent, arsenic trioxide and All-trans retinoic acid; and the treatment for the SC group included hydroxyurea or no active treatment.

Response criteria defined by the International Working Group for Diagnosis, Standardization of Response Criteria, Treatment Outcomes, and Reporting Standards for Therapeutic Trials in AML were used in this study [8].

Statistics

Multivariate analyses of survival were performed using the Cox proportional hazard model. Overall survival (OS) was calculated by Kaplan-Meier survival curves and survival differences between subgroups were compared using log rank test. Independent-samples T test, chi-square test, and likelihood ratio test for trend were used to define the difference in clinical factors among the treatment groups. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS statistical software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Patients' characteristics

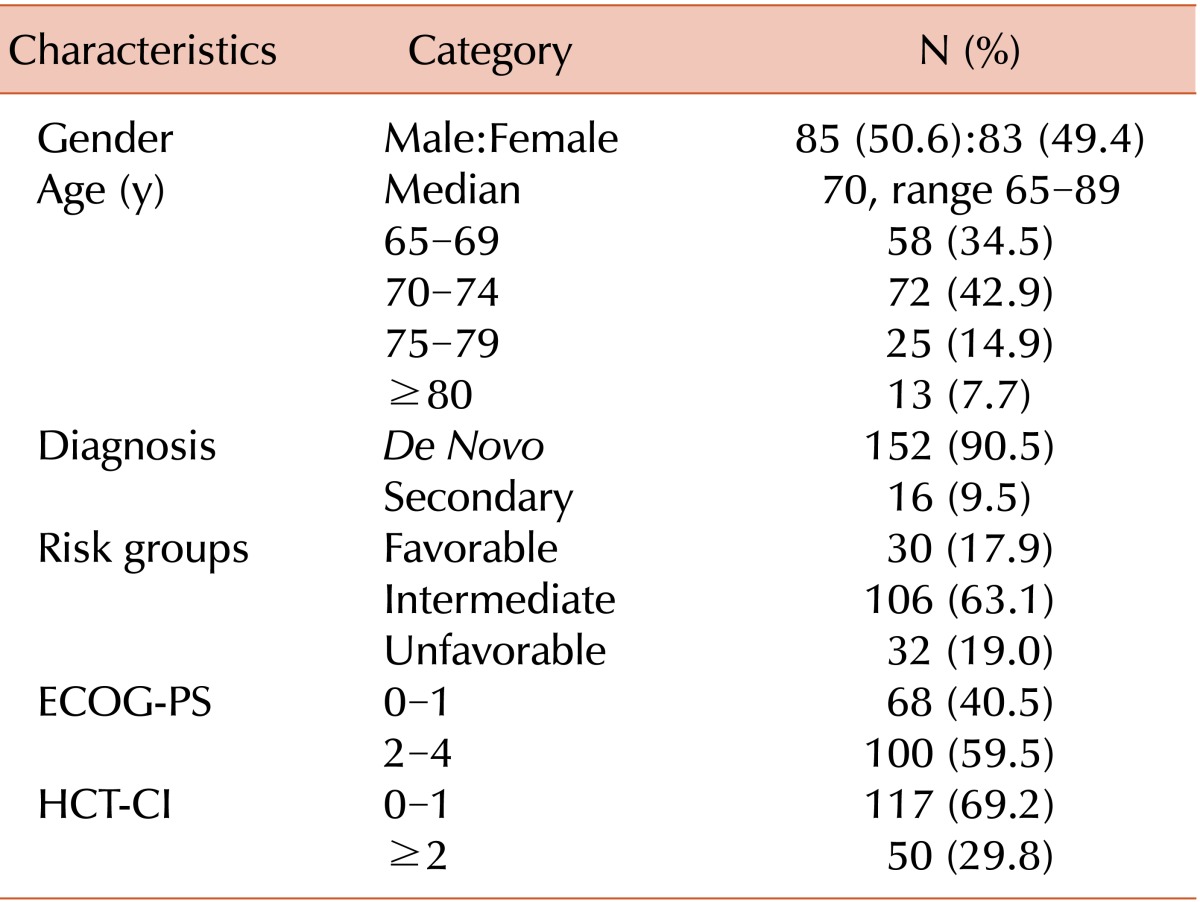

Of the total of 168 patients, the number of male and female patients was 85 and 83, respectively. The median age was 70 years, and most patients had de novo AML (N=152, 90.5%). The intermediate-risk group (N=106, 63.1%) was the largest of the treatment groups. Sixty-eight patients (40.5%) had an ECOG-PS of 0 or 1, and 110 (69.2%) had an HCT-CI of 0 or 1 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patients' characteristics (N=168).

Risk groups were defined according to the Southwest Oncology Group and Medical Research Council criteria.

Abbreviations: ECOG-PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; HCT-CI, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation comorbidity index.

Treatment patterns and outcomes

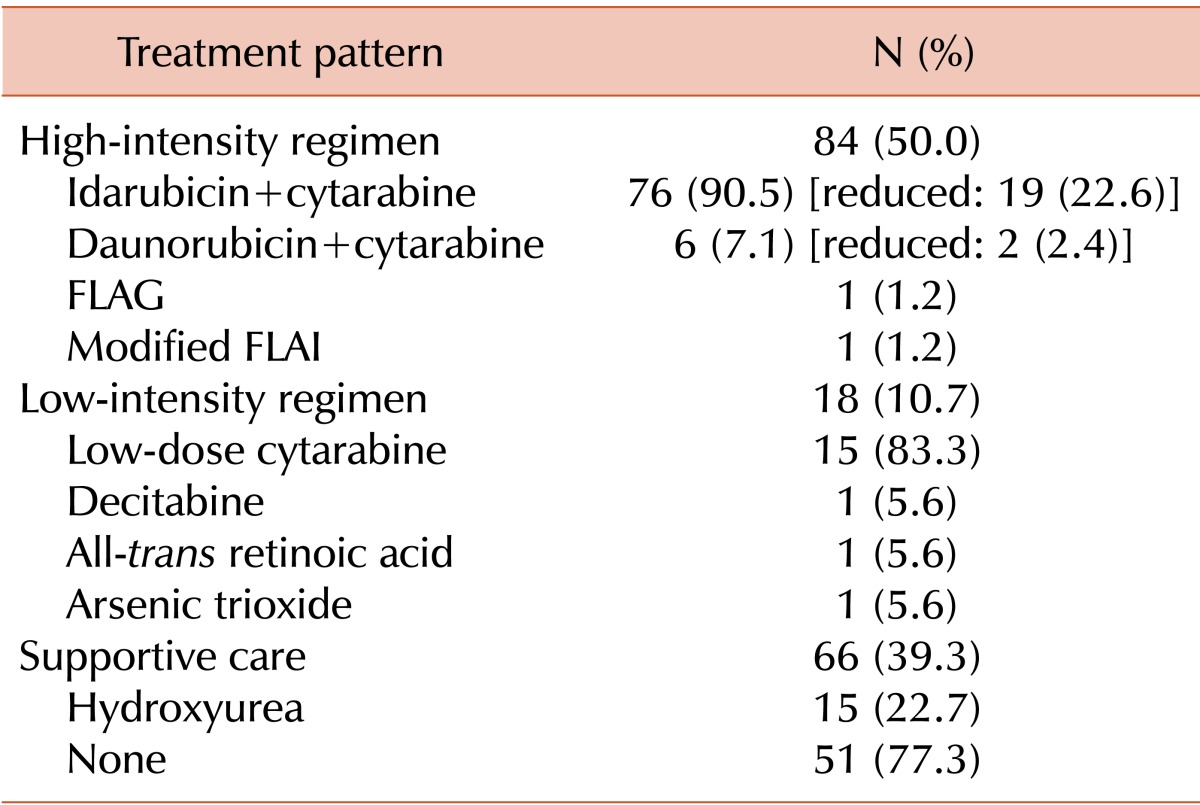

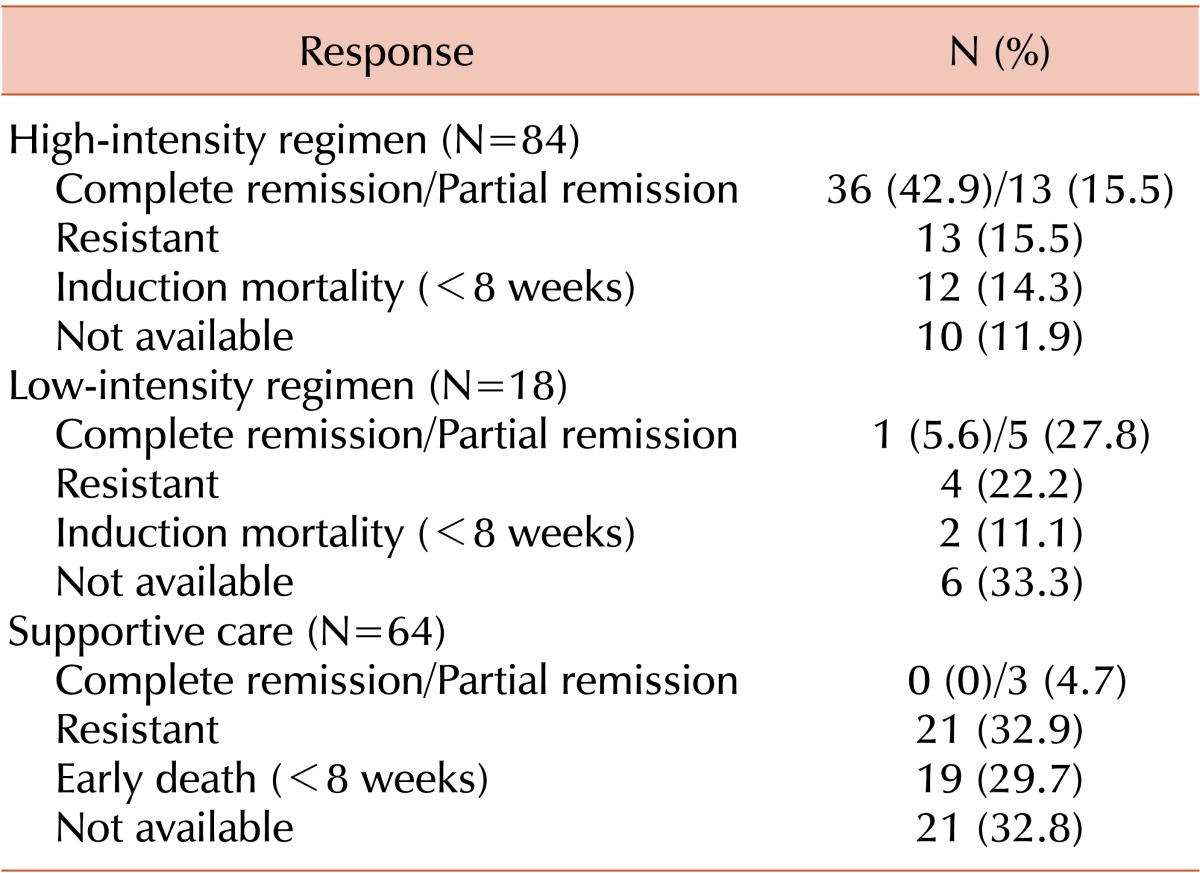

Half of the patients (N=84, 50%) were treated with a HIR, and cytarabine with idarubicin was used mostly (N=76, 90.5%) among these patients. Further, 18 patients (10.7%) belonged to the LIR group and 66 patients (39.3%) to the SC group (Table 2). The response rate in the HIR group was 58.4% (N=49), with complete remission (CR) in 42.9% and partial remission (PR) in 15.5% of the patients. The response rate in the LIR group was 33.3% (CR: 5.6%, PR: 27.8%). Only 3 patients in the SC group achieved PR (Table 3). Response rates in the favorable, intermediate, and unfavorable cytogenetic risk groups were 30% (CR: 20%, PR: 10%), 35.8% (CR: 22.6%, PR: 13.2%), and 34.4% (CR: 21.8%, PR: 12.5%), respectively.

Table 2.

Patterns of induction treatment.

Abbreviations: reduced, reduced dose or infusion day compared to original regimen; FLAG, fludarabine, cytarabine, and G-CSF; FLAI, fludarabine, cytarabine, and idarubicin.

Table 3.

Clinical outcomes according to treatment intensity.

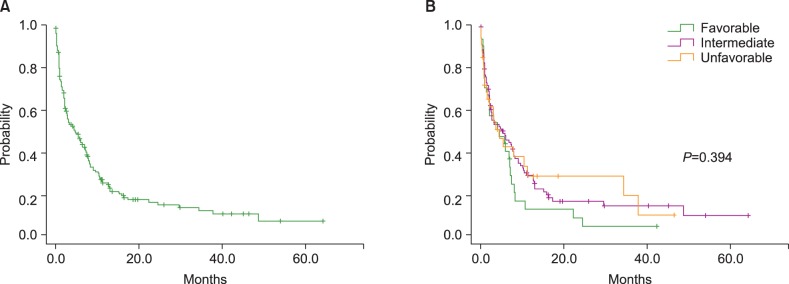

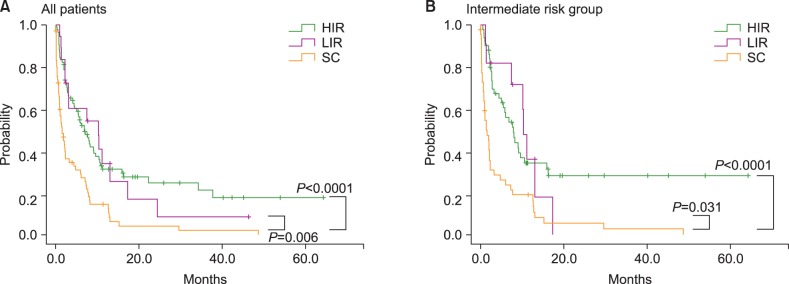

The median survival of all patients was 4.5 months (95% CI: 2.4-6.7 months) (Fig. 1A). Median survival rates in the favorable, intermediate, and unfavorable cytogenetic risk groups were 4.1 months (95% CI: 0.8-9.7 months), 5.0 months (95% CI: 1.6-8.4 months), and 4.5 months (95% CI: 2.4-6.7 months), respectively. There was no significant difference in the survival rates among the cytogenetic risk groups (P=0.394) (Fig. 1B). The median survival rates in the HIR, LIR, and SC treatment groups were 6.8 months (95% CI: 4.4-9.3 months), 10.2 months (95% CI: 0.7-2.5 months), and 1.6 months (95% CI: 1.7-7.4 months), respectively. One-year survival rates in the HIR, LIR, and SC treatment groups were 31%, 26%, and 6%, respectively. Compared to the SC group, median survival was significantly longer in the HIR and LIR groups (P<0.0001 and P=0.006, respectively) (Fig. 2A). Among the 106 patients in the intermediate risk group, the median survival was significantly shorter in the SC treatment group (1.4 months, 95% CI: 0.5-2.3 months) than in the HIR (7.9 months, 95% CI: 5.2-10.6 months) or LIR treatment group (10.3 months, 95% CI: 9.2-11.5 months; P<0.0001 and P=0.031, respectively). There was no survival difference between the HIR and LIR treatment groups (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 1.

(A) The median survival of all patients was 4.5 months (95% CI: 2.4-6.7 months). (B) Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival according to the cytogenetic risk group.

Fig. 2.

(A) Survival comparison according to treatment intensity showed that median survivals in the HIR and LIR groups were significantly longer than that in the SC group. There was no difference in median survival between the HIR and the LIR group. (B) In the intermediate risk group, median survivals in the HIR and LIR groups were significantly longer than that in the SC group (P=0.031). There was no difference in median survival between the HIR and the LIR group. Abbreviations: HIR, high-intensity regimen; LIR, low-intensity regimen; SC, supportive care.

Prognostic factors of survival

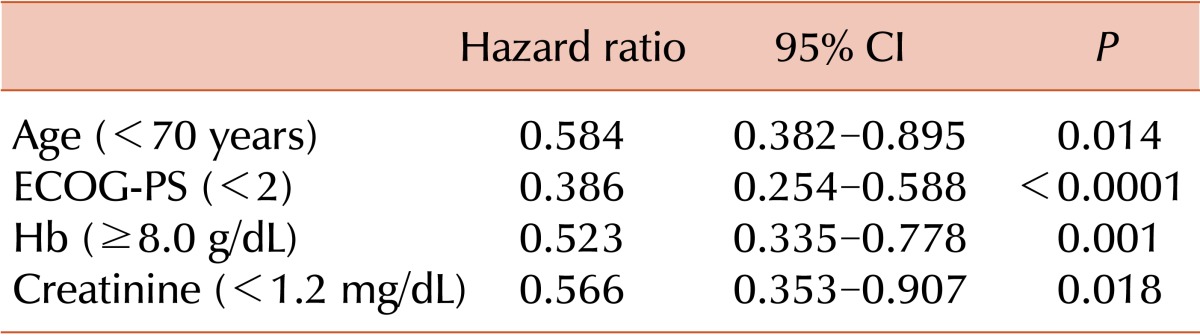

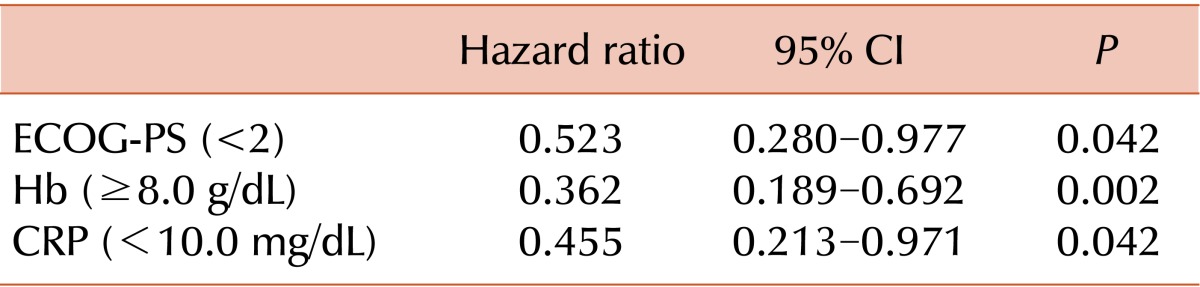

Multivariate analysis with age, ECOG-PS, risk group, HCT-CI, CBC count, creatinine (Cr) level, LDH level, CRP level, and BM blast percent was performed for all patients in each treatment group. Age over 70 years, ECOG-PS, Hb level, and Cr level were proven to be significant prognostic factors of survival for all patients (Table 4). ECOG-PS, Hb level, and CRP level were revealed as significant prognostic factors of survival in the HIR group (Table 5).

Table 4.

Prognostic factors for survival in all patients.

Abbreviations: ECOG-PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; Hb, hemoglobin; CI, confidence interval.

Table 5.

Prognostic factors for survival in high-intensity regimen group.

Abbreviations: ECOG-PS, ECOG performance status; CRP, C-reactive protein.

DISCUSSION

Improvement of survival due to advances in supportive care, chemotherapy regimens, and transplantation techniques has been observed in AML patients [2]. However, elderly AML patients show poor prognosis because of characteristics associated with their age. Characteristics such as fragile medical condition leading to the restriction of active treatments, a higher incidence of treatment-related mortality, and a higher proportion of patients in the high-risk group, including those with high-risk cytogenetic or genetic profiles who may be refractory to treatment, were suggested as the causes of poor clinical outcomes in elderly AML patients [3]. Survival of elderly AML patients has been reported to be only several months [3, 4, 5, 6, 7]. In our study, the median survival of elderly AML patients was 4.5 months, which was a result comparable to those obtained in other studies.

In this study, the median survival in the HIR and LIR groups was significantly longer than that in the SC group among all patients and in the intermediate-risk group. This significant difference among treatment groups was consistently observed even when meaningful prognostic factors such as ECOG-PS, Hb level, and CRP level were forced into the model (P=0.001). A possible explanation for these observations is that the patients who received HIR had more favorable clinical characteristics than those in the SC group. Comparing patients who received the HIR treatment to those in the SC group, the former were younger (average age 70.5±3.7 years vs. 75.7±5.7 years, respectively, P=0.01), had better ECOG-PS (0-1 vs. >1, respectively, P=0.049), had lower HCT-CI (0-1 vs. >1, respectively, P=0.049), had higher average platelet counts (91.0±81.5×109/L vs. 109.0±150.5×109/L, respectively, P=0.029), and had lower average Cr levels (1.0±0.3 mg/dL vs. 1.3±1.6 mg/dL, respectively, P=0.0333). This suggests that careful patient selection for high-intensity treatment with a meaningful use of prognostic factors could result in better clinical outcomes even in elderly AML patients.

Various prognostic or predictive models for elderly AML patients have been suggested to better predict clinical outcomes. Many factors, including age, PS, comorbidity, antecedent hematologic disorders, adverse cytogenetics, LDH level, blood cell counts, liver or kidney function, other laboratory values, and genetic profiles, have been reported as meaningful prognostic or predictive factors [7]. In our multivariate analysis, age, ECOG-PS, Hb level, and Cr level were defined as prognostic factors (Table 4). Because of the higher incidence of treatment-related mortality in elderly AML patients, selecting the optimal treatment intensity is of primary importance in improving clinical outcomes. Intensive treatment could be helpful for selecting patients who are expected to tolerate it. In our study, ECOG-PS, Hb level, and CRP level were suggested to be prognostic factors for the outcomes of intensive treatment (Table 5). However, although other studies have shown significant differences among the survival of general AML patients classified into different cytogenetic risk groups according to the SWOG/MRC criteria, such differences were not observed (P=0.394) in our study. This might be due to several reasons: the cytogenetic diagnosis may not have been accurate enough to enable the classification of each patient into the correct risk group, the lack of a sufficient number of patients, or clinical risk factors such as secondary AML (N=16) and AML with MDS-related changes (N=32), which are not listed in the SWOG/MRC criteria, may have been more common in our elderly AML patients.

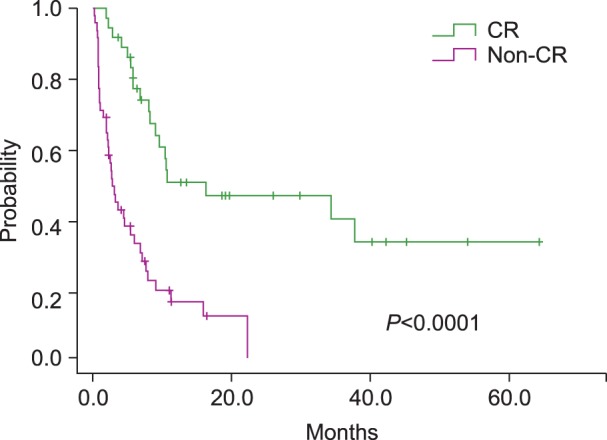

Several phase III trials of intensive chemotherapy given to elderly AML patients reported CR rates of 30-50% after induction of treatment [9, 10, 11]. In our study, CR rate was 42.9% and the response rate was 58.4% in the HIR group. The patients with CR in this group had longer survival than non-CR patients (16.3 months vs. 3.2 months, respectively, P<0.0001) (Fig. 3). There was no significant difference in the responses within the LIR group, probably due to the low number of patients. These results imply that a considerable length of survival can be expected even in elderly AML patients when they show CR with intensive treatment.

Fig. 3.

In the high-intensity regimen group, survival of the patients showing complete remission (CR) was significantly longer than that of patients who did not show CR (non-CR) (P<0.0001).

Even though this study has the limitation of a retrospective study, the results are worthy of notice. This study reports the practical aspects of treatment patterns and outcomes in elderly AML patients in 5 Korean institutes. It shows that clinical characteristics and outcomes in the Korean patients are similar to those in patients of western countries, and highlights the role of the same meaningful prognostic factors such as age, ECOG-PS, Hb level, Cr level, and CRP level. It also suggests that careful selection of patients receiving intensive chemotherapy could bring about better outcomes in elderly AML patients.

Footnotes

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2009 (Vintage 2009 Populations) Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2012. [Accessed March 4 2013]. at http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2009_pops09/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pulte D, Gondos A, Brenner H. Improvements in survival of adults diagnosed with acute myeloblastic leukemia in the early 21st century. Haematologica. 2008;93:594–600. doi: 10.3324/haematol.12304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dombret H, Raffoux E, Gardin C. Acute myeloid leukemia in the elderly. Semin Oncol. 2008;35:430–438. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menzin J, Lang K, Earle CC, Kerney D, Mallick R. The outcomes and costs of acute myeloid leukemia among the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1597–1603. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.14.1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lowenberg B, Downing JR, Burnett A. Acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1051–1062. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909303411407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shin HC, Na II, Yun T, et al. Acute myelogenous leukemia in the elderly (≥60): retrospective study of 115 patients. Korean J Med. 2006;70:196–206. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pollyea DA, Kohrt HE, Medeiros BC. Acute myeloid leukaemia in the elderly: a review. Br J Haematol. 2011;152:524–542. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheson BD, Bennett JM, Kopecky KJ, et al. Revised recommendations of the International Working Group for Diagnosis, Standardization of Response Criteria, Treatment Outcomes, and Reporting Standards for Therapeutic Trials in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4642–4649. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Godwin JE, Kopecky KJ, Head DR, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in elderly patients with previously untreated acute myeloid leukemia: a Southwest oncology group study (9031) Blood. 1998;91:3607–3615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Witz F, Sadoun A, Perrin MC, et al. A placebo-controlled study of recombinant human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor administered during and after induction treatment for de novo acute myelogenous leukemia in elderly patients. Groupe Ouest Est Leucémies Aiguës Myéloblastiques (GOELAM) Blood. 1998;91:2722–2730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldstone AH, Burnett AK, Wheatley K, et al. Attempts to improve treatment outcomes in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in older patients: the results of the United Kingdom Medical Research Council AML11 trial. Blood. 2001;98:1302–1311. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.5.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]