Abstract

Purpose

A Pan-Canadian Practice Guideline on Screening, Assessment, and Care of Psychosocial Distress (Depression, Anxiety) in Adults With Cancer was identified for adaptation.

Methods

American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has a policy and set of procedures for adapting clinical practice guidelines developed by other organizations. The guideline was reviewed for developmental rigor and content applicability.

Results

On the basis of content review of the pan-Canadian guideline, the ASCO panel agreed that, in general, the recommendations were clear, thorough, based on the most relevant scientific evidence, and presented options that will be acceptable to patients. However, for some topics addressed in the pan-Canadian guideline, the ASCO panel formulated a set of adapted recommendations based on local context and practice beliefs of the ad hoc panel members. It is recommended that all patients with cancer be evaluated for symptoms of depression and anxiety at periodic times across the trajectory of care. Assessment should be performed using validated, published measures and procedures. Depending on levels of symptoms and supplementary information, differing treatment pathways are recommended. Failure to identify and treat anxiety and depression increases the risk for poor quality of life and potential disease-related morbidity and mortality. This guideline adaptation is part of a larger survivorship guideline series.

Conclusion

Although clinicians may not be able to prevent some of the chronic or late medical effects of cancer, they have a vital role in mitigating the negative emotional and behavioral sequelae. Recognizing and treating effectively those who manifest symptoms of anxiety or depression will reduce the human cost of cancer.

INTRODUCTION

American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has established a process for adapting other organizations' clinical practice guidelines. This article summarizes the results of that process and presents the practice recommendations adapted from the Pan-Canadian Guideline on Screening, Assessment and Care of Psychosocial Distress (Depression, Anxiety) in Adults with Cancer,1 which addressed the optimum screening, assessment, and psychosocial-supportive care interventions for adults with cancer who are identified as experiencing symptoms of depression and/or anxiety.

This guideline adaptation addresses one of 18 symptom topics that have been identified and prioritized for guideline development by ASCO's Cancer Survivorship Committee. As a result of the growing numbers of cancer survivors,2 ASCO has taken steps to address the recommendations made by the Institute of Medicine (IOM)3 to promote evidenced-based, comprehensive, compassionate, and coordinated survivorship care.4–6 More specifically, ASCO's Cancer Survivorship Committee has mobilized to address recommendation 3 of the IOM, which calls for health care providers to “use of systematically developed evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, assessment tools, and screening instruments to help identify and manage late effects of cancer and its treatment. Existing guidelines should be refined and new evidence-based guidelines should be developed through public- and private-sector efforts.”3(p155)

METHODS

This guideline adaptation was informed by the ADAPTE methodology,7 which was used as an alternative to de novo guideline development for this guideline. Adaptation of guidelines is considered by ASCO in selected circumstances, when one or more quality guidelines from other organizations already exist on the same topic. The objective of the ADAPTE process8 is to take advantage of existing guidelines in order to enhance efficient production, reduce duplication, and promote the local uptake of quality guideline recommendations.

THE BOTTOM LINE.

GUIDELINE QUESTION

What are the optimum screening, assessment, and treatment approaches in the treatment of adult patients with cancer who are experiencing symptoms of depression and anxiety?

Target Population

This guideline adaptation pertains to adults (age 18 years and older) at any phase of the cancer continuum and regardless of cancer type, disease stage, or treatment modality. The guideline does not focus on treatment of depression or anxiety in adults prior to a cancer diagnosis, but recognizes these as risk factors in the assessment process.

Target Audience

Professional health care providers (eg, medical, surgical, and radiation oncologists; psychiatrists; psychologists; primary care providers; nurses; and others involved in the delivery of care for adults with cancer) as well as patients, family members, and caregivers.

Final Recommendations

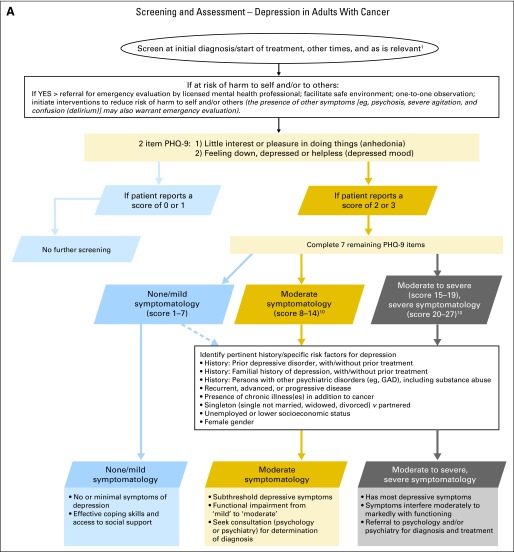

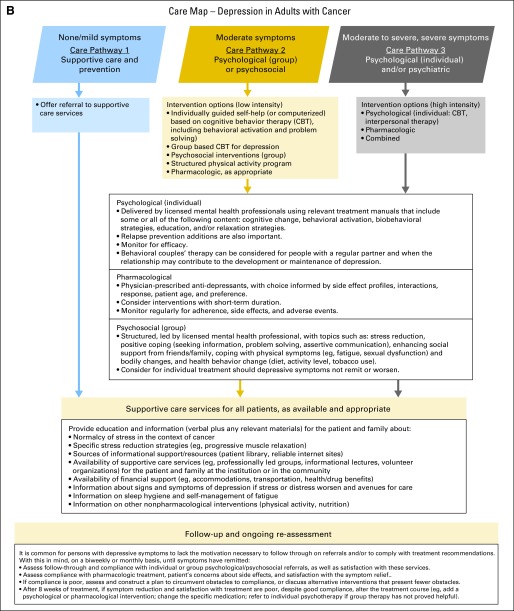

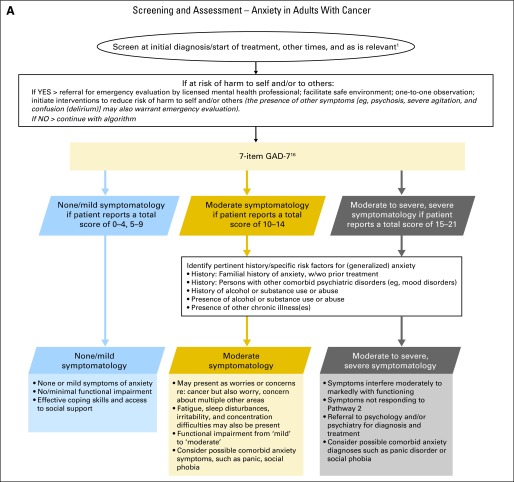

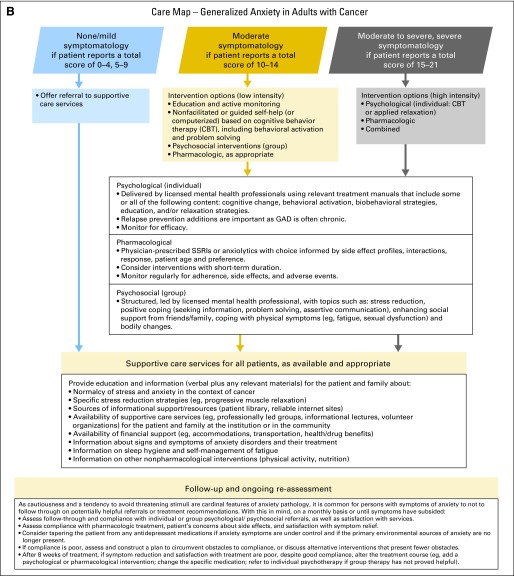

It is recommended that all patients with cancer and cancer survivors be evaluated for symptoms of depression and anxiety at periodic times across the trajectory of care. Assessment should be performed using validated measures. Depending on levels of symptoms reported, different treatment pathways are recommended (Figures 1 and 2). Failure to identify and treat anxiety and depression in the context of cancer increases the risk for poor quality of life, and potentially increased disease-related morbidity and mortality.

Health care practitioners implementing the recommendations presented in this guideline should first identify the available resources in their institution and community for the treatment of depressive and anxiety symptoms. The availability and accessibility of supportive care services for all are important in preventing or reducing the severity of symptoms of psychopathology in patients.

Follow-Up and Re-Assessment

- It is common for persons with symptoms of depression and/or anxiety not to follow through on referrals and/or to comply with treatment recommendations. With this in mind:

- ○ Assess follow-through and compliance with individual or group psychological/psychosocial referrals, as well as satisfaction with these services.

- ○ Assess compliance with pharmacologic treatment, patient's concerns about adverse effects, and satisfaction with the symptom relief provided by the treatment.

- ○ Consider tapering the patient from medications prescribed for anxiety if symptoms are under control and if the primary environmental sources of anxiety are no longer present.

- ○ If compliance is poor, assess and construct a plan to circumvent obstacles to compliance or discuss alternative interventions that present fewer obstacles.

- ○ After 8 weeks of treatment, if symptom reduction and satisfaction with treatment are poor, despite good compliance, alter the treatment course (eg, add a psychological or pharmacological intervention; change the specific medication; refer to individual psychotherapy if group therapy has not proved helpful).

ASCO's adaptation process begins with a literature search to identify candidate guidelines for adaptation. Adapted guideline manuscripts are reviewed and approved by the ASCO Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee (CPGC). The review includes two parts: methodological review and content review. The methodological review is completed by a member of the CPGC's Methodology Subcommittee and/or by ASCO senior guideline staff. The content review is completed by an ad hoc panel (Appendix 1, online only) convened by ASCO that includes multidisciplinary representation. Further details of the methods used for the development of this guideline are reported in a Data Supplement available at www.asco.org/adaptations/depression.

DISCLAIMER

The information contained in, including but not limited to clinical practice guidelines and other guidance is based on the best available evidence at the time of creation and is provided by the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Inc. (“ASCO”) to assist providers in clinical decision making. The information should not be relied on as being complete or accurate, nor should it be considered as inclusive of all proper treatments or methods of care or as a statement of the standard of care. With the rapid development of scientific knowledge, new evidence may emerge between the time information is developed and when it is published or read. The information is not continually updated and may not reflect the most recent evidence. The information addresses only the topics specifically identified therein and is not applicable to other interventions, diseases, or stages of diseases. This information does not mandate any particular product or course of medical treatment. Further, the information is not intended to substitute for the independent professional judgment of the treating provider, as the information does not account for individual variation among patients. Recommendations reflect high, moderate or low confidence that the recommendation reflects the net effect of a given course of action. The use of words like “must,” “must not,” “should,” and “should not” indicate that a course of action is recommended or not recommended for either most or many patients, but there is latitude for the treating physician to select other courses of action in certain cases. In all cases, the selected course of action should be considered by the treating provider in the context of treating the individual patient. Use of the information is voluntary. ASCO provides this information on an “as is” basis, and makes no warranty, express or implied, regarding the information. ASCO specifically disclaims any warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular use or purpose. ASCO assumes no responsibility for any injury or damage to persons or property arising out of or related to any use of this information or for any errors or omissions.

GUIDELINE AND CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The Expert Panel was assembled in accordance with ASCO's Conflict of Interest Management Procedures for Clinical Practice Guidelines (“Procedures,” summarized at http://www.asco.org/rwi). Members of the panel completed ASCO's disclosure form, which requires disclosure of financial and other interests that are relevant to the subject matter of the guideline, including relationships with commercial entities that are reasonably likely to experience direct regulatory or commercial impact as the result of promulgation of the guideline. Categories for disclosure include employment relationships, consulting arrangements, stock ownership, honoraria, research funding, and expert testimony. In accordance with the Procedures, the majority of the members of the panel did not disclose any such relationships.

RESULTS OF GUIDELINE SEARCH AND ASCO PANEL CONTENT REVIEW

As mentioned, the adaptation process starts with a literature search to identify candidate guidelines for adaptation on a given topic. The systematic search of clinical practice guideline databases, guideline developer Web sites, and the published health literature identified clinical practice guidelines, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and other guidance documents addressing the screening, assessment, and care of symptoms of anxiety and/or depression. On the basis of formal content review of the pan-Canadian guideline using a standardized form and on review of the literature search yield, the ad hoc panel selected the pan-Canadian guideline for adaptation because it was comprehensive and recently developed by multidisciplinary panels of experts. (see Data Supplement for details of the search and content review.)

PAN-CANADIAN PRACTICE GUIDELINE: SCREENING, ASSESSMENT AND CARE OF PSYCHOSOCIAL DISTRESS (DEPRESSION, ANXIETY) IN ADULTS WITH CANCER

CLINICAL QUESTIONS AND TARGET POPULATION

The pan-Canadian guideline1 addressed the question, “What are the optimum screening, assessment, and psychosocial-supportive care interventions for adults with cancer who are identified as experiencing symptoms of depression and/or anxiety?”

The target population for the guideline is adults (age 18 years and older) with cancer at any phase of the cancer continuum, regardless of cancer type, disease stage, or treatment modality. The guideline does not focus on the management of depression or anxiety in adults before their cancer diagnosis, but recognizes these as risk factors in the assessment process.

The pan-Canadian guideline is intended to inform Canadian health authorities, program leaders and administrators, as well as professional health care providers engaged in the care of adults with cancer via algorithms and recommendations that would facilitate uptake of the guideline recommendations. The guideline is multidisciplinary in its focus, and the recommendations are applicable to direct-care care providers (eg, nurses, social workers, family practitioners) in diverse care settings.

DEVELOPMENT METHODOLOGY AND THE KEY EVIDENCE

The pan-Canadian guideline was developed by means of the systematic ADAPTE methodology,7 with assessment of the quality of guidelines in accordance with the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) II reporting convention.9 A systematic search of clinical practice guideline databases, guideline developer Web sites, and the published literature was conducted to identify clinical practice guidelines, systematic reviews and other guidance documents that address screening, assessment, and/or treatment of psychosocial distress (depression and anxiety) in adults with cancer. The search of the published literature included searches of the MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and Cochrane Library databases recent to December 2009. The recommendations and algorithms on the optimum screening, assessment, and supportive care of adult patients with cancer who experience depression and/or anxiety were based on the expert consensus of the National Advisory Working Group of the Cancer Journey Action Group, Canadian Partnership Against Cancer, and are informed primarily by five clinical practice guidelines and a number of supporting documents.1

RESULTS OF THE ASCO METHODOLOGIC REVIEW

The methodologic review of the pan-Canadian guideline was completed independently by two ASCO guideline staff members using the Rigour of Development subscale from the AGREE II instrument,9 as discussed above. The score for the Rigour of Development domain is calculated by summing the scores across individual items in the domain and standardizing the total score as a proportion of the maximum possible score. Detailed results of the scoring for this guideline are available on request to guidelines@asco.org. Overall, the pan-Canadian guideline score was 83.3% for methodological quality, with only minor deviations from the ideal as reflected in the AGREE II items.

FINAL RECOMMENDATIONS

On the basis of formal content review of the pan-Canadian guideline, the ASCO panel agreed that, in general, the recommendations were clear, thorough, based on the most relevant scientific evidence, and presented options that will be acceptable to patients. However, for some topics, the ASCO panel formulated a set of adapted recommendations based on local context and practice beliefs of the ad hoc panel members. Additional guidelines and systematic reviews identified in the literature search were used as a supplementary evidence base to inform these adapted recommendations.

The ASCO panel underscores that health care practitioners who implement the recommendations presented in this guideline adaptation should first identify the available resources in their institution and community for the treatment of anxiety and depressive symptoms. The availability and accessibility of supportive care services for all are important in preventing or reducing the severity of symptoms of psychopathology in patients. As a minimum, practitioners should verify with their institution or local hospital the preferred pathway for care of an individual who may present with a mental health emergency.

The sections that follow present the recommendations adapted from the pan-Canadian guideline on screening, assessment, and treatment and care options for depressive symptoms, followed by recommended screening, assessment, and treatment, and care options for anxiety symptoms. Where identified by an asterisk, recommendations are taken verbatim from the pan-Canadian guideline. Otherwise, recommendations have been adapted by the ASCO panel. Recommendations on follow-up and reassessment of symptoms of depression and anxiety were based solely on the consensus of the ASCO panel.

RECOMMENDATIONS ON SCREENING, ASSESSMENT, AND TREATMENT AND CARE OPTIONS FOR DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS

Figure 1 presents a screening, assessment, and care algorithm for depression adapted from the pan-Canadian guideline.1 The algorithm was modified to reflect the ASCO panel's adapted recommendations. Of particular note, references to the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS) screening measure in the recommendations and the algorithm were removed as this measure is not widely used in the United States.

Fig 1.

Depression algorithm. Data adapted with permission.1 GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; PHQ-9, nine-item personal health questionnaire. In this algorithm, the use of the word “depression” refers to the PHQ-9 screening score and not to a clinical diagnosis: (1) initial diagnosis/start of treatment, regular intervals during treatment, 3, 6, and 12 months after treatment, diagnosis of recurrence or progression, when approaching death, and during times of personal transition or reappraisal such as family crisis10a; (2) presence of symptom in the last 2 weeks (rated as 0 = “not at all,” 1 = “several days,” 2 = “more than half the days,” and 3 = “nearly every day”); (3) content of remaining seven items: sleep problems, low energy, appetite, low self-view, concentration difficulties, motor retardation or agitation, and thoughts of self-harm.1 Care map for depression in adults with cancer. Data adapted with permission.1 CBT, cognitive behavior therapy..

Screening

- All patients should be screened for depressive symptoms at their initial visit, at appropriate intervals, and as clinically indicated, especially with changes in disease or treatment status (ie, post-treatment, recurrence, progression) and transition to palliative and end-of-life care.

- ○ The Canadian Association of Psychosocial Oncology (CAPO) and the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer (the Partnership) guideline Assessment of Psychosocial Health Care Needs of the Adult Cancer Patient suggests screening at initial diagnosis, start of treatment, regular intervals during treatment, end of treatment, post-treatment or at transition to survivorship, at recurrence or progression, advanced disease, when dying, and during times of personal transition or reappraisal such as family crisis, during post-treatment survivorship and when approaching death.*

Screening should be done using a valid and reliable measure that features reportable scores (dimensions) that are clinically meaningful (established cut-offs). *

- When assessing a person who may have depressive symptoms, a phased screening and assessment is recommended that does not rely simply on a symptom count.

- ○ As a first step for all patients, identification of the presence or absence of pertinent history or risk factors (see depression algorithm) is important for subsequent assessment and treatment decision making.

- ○ As a second step, two items from the nine-item Personal Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)11 (Table 1) can be used to assess for the classic depressive symptoms of low mood and anhedonia. For individuals who endorse either item (or both) as occurring for more than half of the time or nearly every day within the last 2 weeks (ie, a score of ≥ 2), a third step is suggested in which the patient completes the remaining items of the PHQ-9.11,12 It is estimated that 25% to 30% of patients would need to complete the remaining items. The traditional cutoff for the PHQ-9 is ≥ 10. The Panel's recommended cutoff score of ≥ 8 is based on a study of the diagnostic accuracy of the PHQ-9 with cancer outpatients. A meta-analysis by Manea et al13 also supports the ≥ 8 cutoff score.

- ○ For patients who complete the latter step, it is important to determine the associated sociodemographic, psychiatric or health comorbidities, or social impairments, if any, and the duration of depressive symptoms.

- ○ Of special note, one of remaining seven items of the PHQ-9 assesses thoughts of self harm (ie, “Thoughts that you would be better off dead or hurting yourself in some way”). Among patients with moderate to severe or severe depression, such thoughts are not rare. Having noted that, it is the frequency and/or specificity of the thoughts that are most important vis-à-vis risk. Some clinicians may choose to omit the item from the PHQ-9 and administer eight items. It should be noted, however, that doing so may artificially lower the score, with the risk of some patients appearing to have fewer symptoms than they actually do. Such changes also weaken the predictive validity of the score and the clarity of the cutoff scores. It is important to note that individuals do not typically endorse a self-harm item exclusively or independent of other symptoms; rather, it occurs with several other symptom endorsements. Thus, it is the patient's endorsement of multiple symptoms that will define the need for services for moderate to severe symptomatology.

Consider special circumstances in the assessment of depressive symptoms. These include but are not limited to the following: (1) use culturally sensitive assessments and treatments as is possible, (2) tailor assessment or treatment for those with learning disabilities or cognitive impairments, (3) be aware of the difficulty of detecting depression in the older adult.

Table 1.

PHQ Nine-Symptom Depression Scale and the GAD items

| Item | Ratings |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHQ-9 | ||||

| Over the past two weeks, how often have you been bothered by any of the following problems? | Not at all | Several days | More than half the days | Nearly every day |

| 1. Little interest or pleasure in doing things | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 2. Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 3. Trouble falling or staying asleep, or sleeping too much | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 4. Feeling tired or having little energy | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 5. Poor appetite or overeating | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 6. Feeling bad about yourself—or that you are a failure or have let yourself or your family down | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 7. Trouble concentrating on things, such as reading the newspaper or watching television | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 8. Moving or speaking so slowly that other people could have noticed? Or the opposite—being so fidgety or restless that you have been moving around a lot more than usual | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 9. Thoughts that you would be better off dead or hurting yourself in some way | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Column totals | ||||

| If you checked off any problems, how difficult have these problems made it for you to do your work, take care of things at home, or get along with other people? | Not difficult at all | Somewhat difficult | Very difficult | Extremely difficult |

| GAD-7 | ||||

| Over the past two weeks, how often have you been bothered by the following problems? | Not at all | Several days | More than half the days | Nearly every day |

| 1. Feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 2. Not being able to stop or control worrying | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 3. Worrying too much about different things | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 4. Trouble relaxing | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 5. Being so restless that it is hard to sit still | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 6. Becoming easily annoyed or irritable | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 7. Feeling afraid as if something awful might happen | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Column totals | ||||

| If you checked off any problems, how difficult have these problems made it for you to do your work, take care of things at home, or get along with other people? | Not difficult at all | Somewhat difficult | Very difficult | Extremely difficult |

NOTE. GAD-7 Anxiety Severity score calculated by assigning scores of 0, 1, 2, and 3 to the response categories, respectively, of “not at all,” several days,” “more than half the days,” and “nearly every day.” GAD-7 total score for the seven items ranges from 0 to 21: 0-4: minimal anxiety; 5-9: mild anxiety; 10-14: moderate anxiety; 15-21: severe anxiety.

Abbreviations: GAD, Generalized Anxiety Disorder; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire.

Assessment

Specific concerns such as risk of harm to self and/or others, severe depression or agitation, or the presence of psychosis or confusion (delirium) require immediate referral to a psychiatrist, psychologist, physician, or equivalently trained professional.

Assessments should be a shared responsibility of the clinical team, with designation of those who are expected to conduct assessments as per scope of practice.*

The assessment should identify signs and symptoms of depression, the severity of cancer symptoms (eg, fatigue), possible stressors, risk factors, and times of vulnerability. A range of problem checklists is available to guide the assessment of possible stressors. Examples of these are accessible at www.asco.org/adaptations/depression. Clinicians can amend checklists to include areas not represented or ones unique to their patient populations.

Patients should first be assessed for depressive symptoms using the PHQ-9.11 (Table 1).

Table 2 provides a list of other depressive symptom assessment measures, which can be used in follow-up to the PHQ-911 or as alternatives. Table 2 was modified to include measures of depression and/or anxiety symptoms only.

If moderate to severe or severe symptomatology is detected through screening, individuals should have further diagnostic assessment to identify the nature and extent of the depressive symptoms and the presence or absence of a mood disorder.

Medical or substance-induced causes of significant depressive symptoms (eg, interferon administration) should be determined and treated.

As a shared responsibility, the clinical team must decide when referral to a psychiatrist, psychologist, or equivalently trained professional is needed. This includes, for example, all patients with a PHQ-9 score in the severe range or patients in moderate range but with pertinent history and/or risk factors. Such would be determined using measures with established reliability, validity, and utility (eg, cutoff or normative data available) or standardized diagnostic interviews for assessment and diagnosis of depression.

Table 2.

Selected Measures for Depression and Anxiety (modified from the Pan-Canadian Guideline)

| Measures | Description |

|---|---|

| Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)14 |

|

| Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)14,15,70,71 |

|

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) -716,72 |

|

| Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression Scale (CES-D)17 and short form (CES-D-SF)18 |

|

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire-IV (GAD-Q-IV)19 |

|

| Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS)20 and short form (GDS-SF)21 |

|

| Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D)22–24, 78–80 |

|

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)25 |

|

| Patient Health Questionnaire for Depression (PHQ-9)11 |

|

| Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ)26 and abbreviated form (PSWQ-A)27 |

|

| Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)28 |

|

Treatment and Care Options

For any patient who is identified as at risk of harm to self and/or others, refer to appropriate services for emergency evaluation. Facilitate a safe environment and one-to-one observation, and initiate appropriate harm-reduction interventions.

First, treat medical causes of depressive symptoms (eg, unrelieved symptoms such as pain and fatigue) and delirium (eg, infection or electrolyte imbalance).*

For optimal management of depressive symptoms or diagnosed mood disorder, use pharmacologic and/or nonpharmacologic interventions (eg, psychotherapy, psycho-educational therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and exercise) delivered by appropriately trained individuals.29–39

These guidelines make no recommendations about any specific antidepressant pharmacologic regimen being better than another. The choice of an antidepressant should be informed by the adverse effect profiles of the medications; tolerability of treatment, including the potential for interaction with other current medications; response to prior treatment; and patient preference. Patients should be warned of any potential harm or adverse effects.*

Offer support and provide education and information about depression and its management to all patients and their families, including what specific symptoms and what degree of symptom worsening warrants a call to the physician or nurse.

- Special characteristics of depressive disorders are relevant for diagnosis and treatment, including the following35,36:

- ○ Many individuals (50% to 60%) with a diagnosed depressive disorder will have a comorbid anxiety disorder, with generalized anxiety being the most prevalent.40

- ○ If an individual has comorbid anxiety symptoms or disorder(s), the usual practice is usually to treat the depression first.

- ○ Some people have depression that does not respond to an initial course of treatment.

- It is recommended to use a stepped care model and tailor intervention recommendations based on variables such as the following:

- ○ Current symptomatology level and presence or absence of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-V) diagnosis

- ○ Level of functional impairment in major life areas

- ○ Presence or absence of risk factors

- ○ History of and response to previous treatments for depression

- ○ Patient preference

- ○ Persistence of symptoms after receipt of an initial course of depression treatment

Psychological and psychosocial interventions should derive from relevant treatment manuals for empirically supported treatments that specify the content and guide the structure, delivery mode, and duration of the intervention.

Use of outcome measures should be routine (minimally pre- and post-treatment) to (1) gauge the efficacy of treatment for the individual patient, (2) monitor treatment adherence, and (3) evaluate practitioner competence.

Follow-Up and Reassessment

It is common for persons with depressive symptoms to lack the motivation necessary to follow through on referrals and/or to comply with treatment recommendations. With this in mind, do the following on a biweekly or monthly basis, until symptoms have remitted35,36,41:

○ Assess follow-through and compliance with individual or group psychological or psychosocial referrals, as well as satisfaction with these services.

○ Assess compliance with pharmacologic treatment, patient's concerns about adverse effects, and satisfaction with the symptom relief provided by the treatment.

○ If compliance is poor, assess and construct a plan to circumvent obstacles to compliance, or discuss alternative interventions that present fewer obstacles.

○ After 8 weeks of treatment, if symptom reduction and satisfaction with treatment are poor, despite good compliance, alter the treatment course (eg, add a psychological or pharmacologic intervention, change the specific medication, refer to individual psychotherapy if group therapy has not proved helpful).

RECOMMENDATIONS ON SCREENING, ASSESSMENT, AND TREATMENT AND CARE OPTIONS FOR ANXIETY SYMPTOMS

Figure 2 presents a screening and assessment algorithm for anxiety adapted from the pan-Canadian guideline.1 The algorithm was modified to reflect the ASCO panel's adapted recommendations. Of particular note, references to the ESAS screening measure in the recommendations and the algorithm were removed as this measure is not widely used in the United States.

Fig 2.

Anxiety algorithm. Data adapted with permission.1 GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 scale; w/wo, with or without. In this algorithm, the use of the word “anxiety” refers to GAD-7 scale scores and not to clinical diagnosis of anxiety disorder(s): (1) initial diagnosis/start of treatment, regular intervals during treatment, 3, 6, and 12 months after treatment, diagnosis of recurrence or progression, when approaching death, and during times of personal transition or reappraisal such as family crisis10a; (2) presence of symptom in the last 2 weeks (rated as 0 = “not at all,” 1 = “several days,” 2 = “more than half the days,” and 3 = “nearly every day”); (3) content of items: feeling nervous, anxious, on edge, cannot stop/control worry, worry too much, trouble relaxing, restlessness, easily annoyed, irritable, and feeling afraid. Final item regarding difficulty of the problems. Care map for generalized anxiety in adults with cancer. Data adapted with permission.1 CBT, cognitive behavior therapy; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

As noted, where identified by an asterisk, recommendations were taken verbatim from the pan-Canadian guideline. Otherwise, recommendations were adapted by the ASCO panel. Recommendations on follow-up and reassessment of symptoms of anxiety are based solely on the consensus of the ASCO panel.

Screening

All health care providers should routinely screen for the presence of emotional distress and specifically symptoms of anxiety from the point of diagnosis onward.*

- All patients should be screened for distress at their initial visit, at appropriate intervals and as clinically indicated, especially with changes in disease status (ie, post-treatment, recurrence, progression) and when there is a transition to palliative and end-of-life care.*

- ○ The CAPO and Partnership guideline, Assessment of Psychosocial Health Care Needs of the Adult Cancer Patient, suggests screening at initial diagnosis, start of treatment, regular intervals during treatment, end of treatment, post-treatment or at transition to survivorship, at recurrence or progression, advanced disease, when dying, and during times of personal transition or reappraisal such as family crisis, during post-treatment survivorship and when approaching death.*

Screening should identify the level and nature (problems and concerns) of the distress as a red flag indicator.*

Screening should be done using a valid and reliable tool that features reportable scores (dimensions) that are clinically meaningful (established cut-offs).*

Anxiety disorders include specific phobias and social phobia, panic and agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), obsessive compulsive disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

It is recommended that patients be assessed for GAD, as it is the most prevalent of all anxiety disorders and it is commonly comorbid with others, primarily mood disorders or other anxiety disorders (eg, social anxiety disorder).40

Use of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) -7 scale (Table 1) is recommended. Table 2 provides a list of other assessment measures for symptoms of anxiety, nervousness, and GAD. Table 2 was modified to include scales that measure depression and/or anxiety only.

Patients with GAD do not necessarily present with symptoms of anxiety, per se. The pathognomic GAD symptom (ie, multiple excessive worries) may present as “concerns” or “fears.” Whereas cancer worries may be common for many, GAD worry or fear may be disproportionate to actual cancer-related risk (eg, excessive fear of recurrence, worry about multiple symptoms or symptoms not associated with current disease or treatments). Importantly, an individual with GAD has worries about a range of other, noncancer topics and areas of his or her life.

It is important to determine the associated home, relationship, social, or occupational impairments, if any, and the duration of anxiety-related symptoms. As noted above, problem checklists can be used. Examples of these are accessible at www.asco.org/adaptations/depression. Clinicians can amend the checklists to include additional key problem areas or ones unique to their patient populations.

As with depressive symptoms, consider special circumstances in screening and assessment of anxiety, including using culturally sensitive assessments and treatments and tailoring assessment or treatment for those with learning disabilities or cognitive impairments.

Assessment

Specific concerns such as risk of harm to self and/or others, severe anxiety or agitation, or the presence of psychosis or confusion (delirium) require referral to a psychiatrist, psychologist, physician, or equivalently trained professional.

When moderate to severe or severe symptomatology is detected through screening, individuals should have a diagnostic assessment to identify the nature and extent of the anxiety symptoms and the presence or absence of an anxiety disorder or disorders.

Medical and substance-induced causes of anxiety should be diagnosed and treated.

As a shared responsibility, the clinical team must decide when referral to a psychiatrist, psychologist or equivalently trained professional is needed (ie, all patients with a score in the moderate to severe or severe range, with certain accompanying factors and/or symptoms, identified using valid and reliable measures for assessment of symptoms of anxiety).

Assessments should be a shared responsibility of the clinical team, with designation of those who are expected to conduct assessments as per scope of practice.*

The assessment should identify signs and symptoms of anxiety (eg, panic attacks, trembling, sweating, tachypnea, tachycardia, palpitations, and sweaty palms), severity of symptoms, possible stressors (eg, impaired daily living), risk factors, and times of vulnerability, and should also explore underlying problems/causes.*

A patient considered to have severe symptoms of anxiety after the further assessment should, where possible, have confirmation of an anxiety disorder diagnosis before any treatment options are initiated (eg, DSM-V, which may require making a referral).

Treatment and Care Options

For any patient who is identified as at risk of harm to self and/or others, clinicians should refer to appropriately trained professionals for emergency evaluation. Facilitate a safe environment and one-to-one observation, and initiate appropriate harm-reduction interventions.

It is suggested that the clinical team making a patient referral for the treatment of anxiety review with the patient, in a shared decision process, the reason(s) for and potential benefits of the referral. Further, it is suggested that the clinical team subsequently assess the patient's compliance with the referral and treatment progress or outcomes.

First treat medical causes of anxiety (eg, unrelieved symptoms such as pain and fatigue) and delirium (eg, infection or electrolyte imbalance).*

For optimal management of moderate to severe or severe anxiety, consider pharmacologic and/or nonpharmacologic interventions delivered by appropriately trained individuals. Management must be tailored to individual patients, who should be fully informed of their options.

For a patient with mild to moderate anxiety, the primary oncology team may choose to manage the concerns by usual supportive care.*

The choice of an anxiolytic should be informed by the adverse effect profiles of the medications; tolerability of treatment, including the potential for interaction with other current medications; response to prior treatment; and patient preference. Patients should be warned of any potential harm or adverse effects. Caution is warranted with respect to the use of benzodiazepines in the treatment of anxiety, specifically over the longer term. These medications carry an increased risk of abuse and dependence and are associated with adverse effects that include cognitive impairment. As a consequence, use of these medications should be time limited in accordance with established psychiatric guidelines.42

Offer support and provide education and information to all patients and their families about anxiety and its treatment and what specific symptoms or symptom worsening warrant a call to the physician or nurse.

- It is recommended to use a stepped care model to tailor intervention recommendations on the basis of variables such as the following:

- ○ Current symptomatology level and presence/absence of DSM-V diagnoses

- ○ Level of functional impairment in major life areas

- ○ Presence/absence of risk factors

- ○ Chronicity of GAD and response to previous treatments, if any

- ○ Patient preference

- ○ Persistence of symptoms after receipt of the current anxiety treatment.

Psychological and psychosocial interventions should be derived from relevant treatment manuals of empirically supported treatments that specify the content and guide the structure, delivery mode, and duration of the intervention. Use of outcome measures should be routine (minimally pre- and post-treatment) to (1) gauge the efficacy of treatment for the individual patient, (2) monitor treatment adherence, and (3) evaluate practitioner competence.

Follow-Up and Reassessment

- Because cautiousness and a tendency to avoid threatening stimuli are cardinal features of anxiety pathology, it is common for persons with symptoms of anxiety not to follow through on potentially helpful referrals or treatment recommendations.35,43 With this in mind, it is recommended that the mental health professional or other member of the clinical team treating the patient's anxiety, on a monthly basis or until symptoms have subsided:

- ○ Assess follow-through and compliance with individual or group psychological or psychosocial referrals, as well as satisfaction with the treatment.

- ○ Assess compliance with pharmacologic treatment, patient's concerns about adverse effects, and satisfaction with the symptom relief provided by the treatment.

- ○ Consider tapering the patient from medications prescribed for anxiety if symptoms are under control and if the primary environmental sources of anxiety are no longer present. Longer periods of tapering are often necessary with benzodiazepines, particularly with potent or rapidly eliminated medications.

- ○ If compliance is poor, assess and construct a plan to circumvent obstacles to compliance, or discuss alternative interventions that present fewer obstacles.

- ○ After 8 weeks of treatment, if symptom reduction and satisfaction with treatment are poor, despite good compliance, alter the treatment course (eg, add a psychological or pharmacologic intervention, change the specific medication, refer to individual psychotherapy if group therapy has not proved helpful).

SPECIAL COMMENTARY

As noted in the 2008 Institute of Medicine report, “Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs” (IOM, 2008), and confirmed in a recent report,44 the psychological needs of patients with cancer are not being addressed, posing a serious problem for US health care. The days surrounding the diagnosis and initiation of treatment are the most stressful.45,46 If psychological needs are not addressed, regardless of when they arise, they then predict later stress and anxiety,47,48 depressive symptoms,49 low quality of life,50 increased adverse effects, and more physical symptoms.51–54 Alternatively, treatment for either anxiety or depression can successfully addresses issues such as these32,55 and has the potential to reduce the risk of recurrence56 or cancer death.51–53,57

The present guideline adaptation is a step toward assistance and guidance for the oncology community for the assessment of depressive and anxiety symptoms. A busy medical staff may not recognize depression or anxiety disorders. Indeed, studies show that detection of depression is low;58,59 severity is underestimated;58–60 and, even when treated with medications, the dose is inadequate.61,62 These data are juxtaposed with the knowledge that psychiatric disorders are more prevalent among patients with cancer than among those with any other chronic illness.63 Though studies vary, the point prevalence estimates for patients with cancer have been estimated to be 20.7% for any mood disorder, 10.3% for anxiety disorders, and 19.4% for any adjustment disorder.64 By comparison, the National Institute of Mental Health reports 12-month prevalence estimates as being 9.5 for mood disorders and 18.1 for anxiety disorders.40

Clinicians may not be able to prevent some of the chronic or late medical effects of cancer. But they have a vital role in preventing or reducing emotional fall-out at diagnosis and thereafter. Consider the case of depression. Overall, mood disorders are associated with lowered quality of life and soaring health care costs.65,66 Depressed patients with cancer have worries about their disease (70%), relationships with friends (77%), the well-being of family members (74%), and finances (63%),67 and the sequelae of this includes more symptom distress68–70 and maladaptive coping,71 among others. Depression in particular is associated with heightened risk for premature mortality (relative risk = 1.22-1.39) and cancer death (relative risk = 1.18).53,72 Two studies have now documented increased rates of suicide among populations of long-term breast and testicular cancer survivors.73,74

The picture is no less worrisome when anxiety or anxiety disorders are considered. In fact, a recent meta-analysis has shown that anxiety is the most common mental health issue among long-term cancer survivors.75 As assessed with self-report measures in individuals at least 2 years post diagnosis, prevalence of significant symptoms of depression and anxiety was estimated to be 11.6% and 17.9%, respectively.75 As is the case for persons without concurrent physical illness, depression and anxiety co-occur among patients with cancer.76 Heightened anxiety is also associated with increased adverse effects and symptoms77 and poorer physical functioning.78 Worry, the hallmark of generalized anxiety disorder, can be multifocal,79 with content changing over time, shifting from treatment concerns to physical symptoms and limitations.80 Be it stress, anxiety, or worry, all are related to important neuroendocrine changes,81 which may account in part for the poorer survival among patients with cancer who experience heightened stress.82

Increasingly clinicians are recognizing that for many survivors, their experience of cancer does not end with the conclusion of therapy.3 Many survivors have lingering issues that can affect all aspects of their lives. These run the gamut: physical (pain, fatigue, urinary or bowel problems, sexual dysfunction), psychological (fear of recurrence, body image distress), social (job loss or lock, change in interpersonal relationships), existential (loss of sense of self or self-esteem, change in life meaning and purpose), or financial worries, among others. Unfortunately, long-term cancer survivors are not immune from psychological distress. There may be latent risk. Not only is there the risk for new or recurrent cancer,83 but there also may be emerging chronicities such as cardiac disease, osteoporosis, diabetes, or generally poor health84,85 that take a toll on emotional well-being.

Screening and early, efficacious treatment for those manifesting significant symptoms of anxiety or depression hold the potential to reduce the human cost of cancer, not only for patients and survivors, but also for those who care for and about them. Strong patient/physician rapport will help to assess the patient's experience of depression and anxiety and determine the most appropriate treatment strategy.3,86 In addition, there is a need for physicians to regularly reassess the patient's status to determine whether the first course of treatment for anxiety or depression is effective, or if not, what timely treatment modifications can be implemented.86 On completion of cancer therapy, many patients may be transitioned to a primary health care provider or other health care providers for follow-up. This transition may be difficult for some patients and may be eased with provision of a survivorship care plan containing personalized information about the patient's treatment and follow-up plans, as well as which providers will be responsible for what aspects of survivors' physical and emotional health care needs (see ASCO templates for examples www.cancer.net/survivorship/asco-cancer-treatment-summaries).

In closing, it must be noted that upwards of 50% of patients with cancer do well, manifesting remarkable resilience at diagnosis, treatment, and thereafter. But even when psychological responses during active treatment are satisfactory, a subgroup of patients will still be vulnerable to later distress.87 Regardless of the timing and circumstances by which psychiatric comorbidity arises, there can be enormous emotional, interpersonal, and financial costs for patients, as well as economic consequences for providers and the health care system alike when depressive and anxiety disorders are not treated. The present adapted guideline recommendations are offered as a step toward recognizing and eliminating these gaps in care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Tom Oliver, Christina Lacchetti, Rose Morrison, and Kaitlin Einhaus for administrative assistance, as well as the Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee (CPGC) and the CPGC reviewers for their thoughtful reviews and insightful comments on this guideline document.

Note: Opinions expressed in this article should not be interpreted as official positions of the National Cancer Institute, the National Institutes of Health, or the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Appendix

Table A1.

Members of the Depression and Anxiety Expert Panel

| Name | Institution |

|---|---|

| Barbara L. Andersen, PhD, Co-Chair | Ohio State University |

| Julia H. Rowland, PhD, Co-Chair | National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services |

| Barry S. Berman, MD, MS | Broward Health Medical Center |

| Victoria L. Champion, PhD, RN, FAAN | Indiana University |

| Robert J. DeRubeis, PhD | University of Pennsylvania |

| Jessie Gruman, Patient Representative | Centre for Advancing Health |

| Jimmie Holland, MD | Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center |

| Mary Jane Massie, MD | Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center |

| Ann H. Partridge, MD | Dana-Farber Cancer Institute |

Footnotes

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

Reprint requests: American Society of Clinical Oncology, 2318 Mill Rd, Suite 800, Alexandria, VA 22314; e-mail: guidelines@asco.org.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Additional Information including Data Supplements, evidence tables, and clinical tools and resources can be found at www.asco.org/adaptations/depression. Patient information is available there and at www.cancer.net.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Administrative support: Kate Bak, Mark R. Somerfield

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Howell D, Keller-Olaman S, Oliver T, et al. A pan-Canadian practice guideline: Screening, assessment and care of psychosocial distress (depression, anxiety) in adults with cancer. Canadian Partnership Against Cancer (Cancer Journey Action Group) and the Canadian Association of Psychosocial Oncology, 2010. www.capo.ca/pdf/ENGLISH_Depression_Anxiety_Guidelines_for_Posting_Sept2011.pdf.

- 2.American Cancer Society. Cancer treatment and survivorship facts & figures 2012-2013. American Cancer Society, 2012. www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-033876.pdf.

- 3.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall EE. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2006. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ganz PA, Earle CC, Goodwin PJ. Journal of Clinical Oncology update on progress in cancer survivorship care and research. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3655–3656. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.3886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCabe MS, Bhatia S, Oeffinger KC, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology statement: Achieving high-quality cancer survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:631–640. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.6854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rowland JH, Hewitt M, Ganz PA. Cancer survivorship: A new challenge in delivering quality cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5101–5104. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.ADAPTE Collaboration. The ADAPTE process: Resource toolkit for guideline adaptation (version 2.0) Guidelines International Network, 2009. www.g-i-n.net.

- 8.ADAPTE. http://www.adapte.org.

- 9.AGREE. Advancing the science of practice guidelines. www.agreetrust.org.

- 10.Thekkumpurath P, Walker J, Butcher I, et al. Screening for major depression in cancer outpatients: The diagnostic accuracy of the 9-item patient health questionnaire. Cancer. 2011;117:218–227. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10a.Howell D, Currie S, Mayo S, et al. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Partnership Against Cancer (Cancer Journey Action Group) and the Canadian Association of Psychosocial Oncology; 2009. A pan-Canadian clinical practice guideline: Assessment of psychosocial health care needs of the adult cancer patient. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arroll B, Goodyear-Smith F, Crengle S, et al. Validation of PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 to screen for major depression in the primary care population. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8:348–353. doi: 10.1370/afm.1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manea L, Gilbody S, McMillan D. Optimal cut-off score for diagnosing depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): A meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2012;184:E191–E196. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.110829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, et al. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beck AT, Beck RW. Screening depressed patients in family practice: A rapid technique. Postgrad Med. 1972:81–85. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1972.11713319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psych Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kohout FJ, Berkman LF, Evans DA, et al. Two shorter forms of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression) depression symptoms index. J Aging Health. 1993;5:179–193. doi: 10.1177/089826439300500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newman MG, Zuellig AR, Kachin KE, et al. Preliminary reliability and validity of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire-IV: A revised self-report diagnostic measure of generalized anxiety disorder. Behav Ther. 2002;33:215–233. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yesavage JA, Sheikh JI. 9/Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): Recent evidence and development of a shorter violence. Clin Gerontol. 1986;51:165–173. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yesavage JA, Brink T, Rose TL, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1983;17:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol. 1967;6:278–296. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1967.tb00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller IW, Bishop S, Norman WH, et al. The Modified Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression: Reliability and validity. Psychiatry Res. 1985;14:131–142. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(85)90057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyer TJ, Miller ML, Metzger RL, et al. Development and validation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behav Res Ther. 1990;28:487–495. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(90)90135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hopko DR, Stanley MA, Reas DL, et al. Assessing worry in older adults: Confirmatory factor analysis of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire and psychometric properties of an abbreviated model. Psychol Assess. 2003;15:173. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.15.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, et al. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983. State Trait Anxiety Inventory for Adults Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akechi T, Okuyama T, Onishi J, et al. Psychotherapy for depression among incurable cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008:CD005537. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005537.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown JC, Huedo-Medina TB, Pescatello LS, et al. The efficacy of exercise in reducing depressive symptoms among cancer survivors: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30955. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duijts SF, Faber MM, Oldenburg HS, et al. Effectiveness of behavioral techniques and physical exercise on psychosocial functioning and health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients and survivors–A meta-analysis. Psychooncology. 2011;20:115–126. doi: 10.1002/pon.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Faller H, Schuler M, Richard M, et al. Effects of psycho-oncologic interventions on emotional distress and quality of life in adult patients with cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:782–793. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.8922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hart SL, Hoyt MA, Diefenbach M, et al. Meta-analysis of efficacy of interventions for elevated depressive symptoms in adults diagnosed with cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:990–1004. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rimer J, Dwan K, Lawlor DA, et al. Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;7:CD004366. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004366.pub5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Clinical Practice Guideline 90. Depression: The treatment and management of depression in adults. http://publications.nice.org.uk/depression-in-adults-cg90.

- 36.Thota AB, Sipe TA, Byard GJ, et al. Collaborative care to improve the management of depressive disorders: A community guide systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42:525–538. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Amsterdam JD, et al. Cognitive therapy vs medications in the treatment of moderate to severe depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:409–416. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.4.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dimidjian S, Hollon SD, Dobson KS, et al. Randomized trial of behavioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the acute treatment of adults with major depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:658–670. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.4.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hollon SD, DeRubeis RJ, Shelton RC, et al. Prevention of relapse following cognitive therapy vs medications in moderate to severe depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:417–422. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.4.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, et al. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Waxmonsky JA, Thomas M, Giese A, et al. Evaluating depression care management in a community setting: Main outcomes for a Medicaid HMO population with multiple medical and psychiatric comorbidities. Depress Res Treat. 2012;2012:769298. doi: 10.1155/2012/769298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ashton H. The diagnosis and management of benzodiazepine dependence. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2005;18:249–255. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000165594.60434.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Swinson RP, Antony MM, Bleau P, et al. Clinical practice guidelines management of anxiety disorders. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51(suppl 2):1S–93S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Forsythe LP, Kent EE, Weaver KE, et al. Receipt of psychosocial care among cancer survivors in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1961–1969. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.2101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Andersen BL, Farrar WB, Golden-Kreutz D, et al. Stress and immune responses after surgical treatment for regional breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:30–36. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.1.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blomberg BB, Alvarez JP, Diaz A, et al. Psychosocial adaptation and cellular immunity in breast cancer patients in the weeks after surgery: An exploratory study. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67:369–376. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thornton LM, Andersen BL, Crespin TR, et al. Individual trajectories in stress covary with immunity during recovery from cancer diagnosis and treatments. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:185–194. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Traeger L, Greer JA, Fernandez-Robles C, et al. Evidence-based treatment of anxiety in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1197–1205. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu SM, Andersen BL. Stress generation over the course of breast cancer survivorship. J Behav Med. 2010;33:250–257. doi: 10.1007/s10865-010-9255-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang HC, Brothers BM, Andersen BL. Stress and quality of life in breast cancer recurrence: Moderation or mediation of coping? Ann Behav Med. 2008;35:188–197. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9016-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Giese-Davis J, Collie K, Rancourt KM, et al. Decrease in depression symptoms is associated with longer survival in patients with metastatic breast cancer: A secondary analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:413–420. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.4455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hjerl K, Andersen EW, Keiding N, et al. Depression as a prognostic factor for breast cancer mortality. Psychosomatics. 2003;44:24–30. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.44.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pinquart M, Duberstein PR. Depression and cancer mortality: A meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2010;40:1797–1810. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709992285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Trudel-Fitzgerald C, Savard J, Ivers H. Which symptoms come first? Exploration of temporal relationships between cancer-related symptoms over an 18-month period. Ann Behav Med. 2013;45:329–337. doi: 10.1007/s12160-012-9459-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stanton AL. Psychosocial concerns and interventions for cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5132–5137. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.8775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Andersen BL, Yang HC, Farrar WB, et al. Psychologic intervention improves survival for breast cancer patients: A randomized clinical trial. Cancer. 2008;113:3450–3458. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Andersen BL, Thornton LM, Shapiro CL, et al. Biobehavioral, immune, and health benefits following recurrence for psychological intervention participants. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:3270–3278. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McDonald MV, Passik SD, Dugan W, et al. Nurses' recognition of depression in their patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1999;26:593–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Newell S, Sanson-Fisher RW, Girgis A, et al. How well do medical oncologists' perceptions reflect their patients' reported physical and psychosocial problems? Data from a survey of five oncologists. Cancer. 1998;83:1640–1651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Keller MB, McCullough JP, Klein DN, et al. A comparison of nefazodone, the cognitive behavioral-analysis system of psychotherapy, and their combination for the treatment of chronic depression. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1462–1470. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005183422001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ashbury FD, Madlensky L, Raich P, et al. Antidepressant prescribing in community cancer care. Support Care Cancer. 2003;11:278–285. doi: 10.1007/s00520-003-0446-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sharpe M, Strong V, Allen K, et al. Major depression in outpatients attending a regional cancer centre: Screening and unmet treatment needs. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:314–320. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Evans DL, Charney DS, Lewis L, et al. Mood disorders in the medically ill: Scientific review and recommendations. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:175–189. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: A meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:160–174. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70002-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Olfson M, Marcus SC, Druss B, et al. National trends in the outpatient treatment of depression. JAMA. 2002;287:203–209. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rapaport MH, Clary C, Fayyad R, et al. Quality-of-life impairment in depressive and anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1171–1178. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kleiboer A, Bennett F, Hodges L, et al. The problems reported by cancer patients with major depression. Psychooncology. 2011;20:62–68. doi: 10.1002/pon.1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mystakidou K, Tsilika E, Parpa E, et al. Assessment of anxiety and depression in advanced cancer patients and their relationship with quality of life. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:1825–1833. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-4324-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sadler IJ, Jacobsen PB, Booth-Jones M, et al. Preliminary evaluation of a clinical syndrome approach to assessing cancer-related fatigue. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;23:406–416. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00388-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Smith EM, Gomm SA, Dickens CM. Assessing the independent contribution to quality of life from anxiety and depression in patients with advanced cancer. Palliat Med. 2003;17:509–513. doi: 10.1191/0269216303pm781oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Carver CS, Pozo C, Harris SD, et al. How coping mediates the effect of optimism on distress: A study of women with early stage breast cancer. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1993;65:375–390. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.2.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Satin JR, Linden W, Phillips MJ. Depression as a predictor of disease progression and mortality in cancer patients: A meta-analysis. Cancer. 2009;115:5349–5361. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Beard CJ, Travis LB, Chen MH, et al. Outcomes in stage I testicular seminoma: A population-based study of 9193 patients. Cancer. 2013 doi: 10.1002/cncr.28086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schairer C, Brown LM, Chen BE, et al. Suicide after breast cancer: An international population-based study of 723,810 women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1416–1419. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mitchell AJ, Ferguson DW, Gill J, et al. Depression and anxiety in long-term cancer survivors compared with spouses and healthy controls: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:721–732. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70244-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stark D, Kiely M, Smith A, et al. Anxiety disorders in cancer patients: Their nature, associations, and relation to quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3137–3148. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Teunissen SC, de Graeff A, Voest EE, et al. Are anxiety and depressed mood related to physical symptom burden? A study in hospitalized advanced cancer patients. Palliat Med. 2007;21:341–346. doi: 10.1177/0269216307079067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Aass N, Fossa SD, Dahl AA, et al. Prevalence of anxiety and depression in cancer patients seen at the Norwegian Radium Hospital. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:1597–1604. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(97)00054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ashing-Giwa KT, Padilla G, Tejero J, et al. Understanding the breast cancer experience of women: A qualitative study of African American, Asian American, Latina and Caucasian cancer survivors Psychooncology. 2004;13:408–428. doi: 10.1002/pon.750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Booth K, Beaver K, Kitchener H, et al. Women's experiences of information, psychological distress and worry after treatment for gynaecological cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;56:225–232. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Miller GE, Chen E, Zhou ES. If it goes up, must it come down? Chronic stress and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis in humans. Psychol Bull. 2007;133:25–45. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chida Y, Hamer M, Wardle J, et al. Do stress-related psychosocial factors contribute to cancer incidence and survival? Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2008;5:466–475. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wood ME, Vogel V, Ng A, et al. Second malignant neoplasms: Assessment and strategies for risk reduction. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3734–3745. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.8681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lenihan DJ, Cardinale DM. Late cardiac effects of cancer treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3657–3664. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.2938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lustberg MB, Reinbolt RE, Shapiro CL. Bone health in adult cancer survivorship. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3665–3674. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2007. Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Helgeson VS, Snyder P, Seltman H. Psychological and physical adjustment to breast cancer over 4 years: Identifying distinct trajectories of change. Health Psychol. 2004;23:3–15. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.