Abstract

It has now become universally accepted that hydrogen sulfide (H2S), previously considered only as a lethal toxin, has robust cytoprotective actions in multiple organ systems. The diverse signaling profile of H2S impacts multiple pathways to exert cytoprotective actions in a number of pathological states. This paper will review the recently described cardioprotective actions of hydrogen sulfide in both myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury and congestive heart failure.

1. Introduction

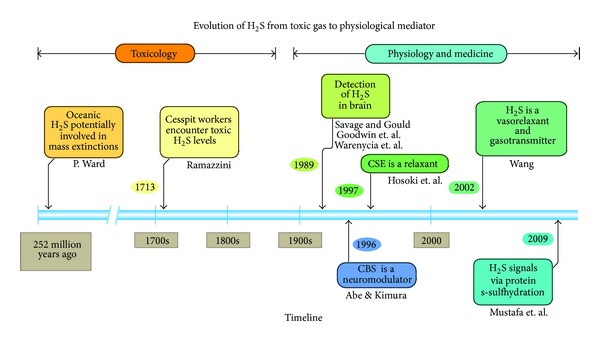

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) has long been viewed simply as a toxic gas with an odorous smell. Its dangerous properties were recognized as far back as the 18th Century when cesspit workers exposed to high environmental levels of H2S developed eye inflammation and bacterial infection [1] (Figure 1). More recently, however, H2S was discovered to exist endogenously and has emerged as an omnipotent signaling molecule, specifically in the cardiovascular system [2–7]. Several years ago, cardiovascular researchers largely focused on the other gaseous signaling molecules, nitric oxide (NO) and carbon dioxide (CO). Consensus formed that NO and CO based therapies protect the brain, heart, and circulation against a number of cardiovascular diseases [8–14]. Because endogenously produced H2S is a gaseous signaling molecule capable of regulating physiological processes (similar to NO and CO), we investigated its potential role as a cardioprotective agent. Our group has shown specifically that H2S protects against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (MI/R) injury and preserves cardiac function following the onset of heart failure in various preclinical model systems.

Figure 1.

History of the emergence of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) as a physiological regulator of cardiovascular homeostasis. H2S is believed to be responsible for mass extinctions that occurred over 250 million years ago as toxic gases were spewed from deep in the earth. In the 1700s, H2S was linked to injuries sustained by sewer workers. In 1989, H2S was detected in the brain of mammals by several groups. In 1996-1997, H2S was shown to modulate vascular tone and neuronal function. Finally in 2002, H2S was implicated in vascular function and blood pressure regulation in seminal studies. H2S was then shown to posttranslationally modify proteins via s-sulfhydration by Dr. Sol Snyder's group. Adopted from Hideo Kimura, Ph.D. Ward [71], Savage and Gould [72], Goodwin et al. [73], Warenycia et al. [74], and Mustafa et al. [75].

2. Endogenous Synthesis of Hydrogen Sulfide in Mammals

Experimental studies reveal that H2S is produced at nano- to micromolar levels both enzymatically and nonenzymatically [15]. The continuous enzymatic production is critical due to the extremely short biological half-life of the molecule (estimated to be between seconds to minutes) [16, 17]. Nonenzymatic H2S can form via the reduction of thiol-containing molecules when H2S is released from sulfur stores such as sulfane sulfur. Two H2S producing enzymes are part of the cysteine biosynthesis pathway: cystathionine gamma lyase (CSE) and cystathionine beta synthase (CBS). These enzymes coordinate with L-cysteine to produce H2S, L-serine, pyruvate, and ammonia [2, 4]. Originally, the endogenous production of H2S in the brain was attributed to CBS [18]. However, more recently, the third enzyme, 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (3-MST), was reported to manufacture roughly 90% of H2S in the brain and is largely concentrated in the mitochondria [19]. 3-MST produces H2S from α-ketoglutarate and L-cysteine via metabolic actions with cysteine aminotransferase and glutamate [19]. The distribution and function of CBS, CSE, and 3-MST under normal physiological conditions remain controversial and unclear. However, we have found that all 3 enzymes are expressed in the heart [20] and a global genetic deletion of CSE (global CBS and 3MST KO mice have not yet been reported) results in significant reductions in myocardial and circulating H2S and sulfane sulfur levels [21]. As this field advances, more discoveries will likely unfold and give us more insight into the physiological mechanism of these enzymes.

3. Hydrogen Sulfide and Myocardial Infarction

Myocardial infarction remains a leading cause of mortality worldwide [22]. It is well established that myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (MI/R) injury stimulates tissue destruction and often leads to heart failure [23]. While reperfusion relieves ischemia, it also results in a complex reaction that leads to cell injury caused by inflammation and oxidative damage [24]. In the first study, to establish an in vivo model for MI/R in mice, the left coronary artery (LCA) was transiently ligated and reperfusion followed by removal of the ligating suture [25]. Following 30 minutes of ischemia, mice were administered sodium sulfide (Na2S) (50 μg/kg) into the left ventricle (LV) lumen. Mice receiving the donor at the time of reperfusion displayed a 72% reduction in infarct size compared to the vehicle treated mice [25]. Cardiac troponin-I (cTnI) evaluation, an additional marker for myocardial injury, also affirmed myocardial preservation in the H2S treated group. Additionally, LV echocardiographic analysis following 72 hours of reperfusion revealed that H2S treated mice displayed no increase in post-MI/-R LV dimensions (left ventricular end-diastolic dimensions and left ventricular end-systolic dimensions), while the vehicle treated group showed significantly increased wall thickening [25].

A subsequent study examined the impact of genetically modifying an enzyme responsible for much of endogenous H2S production (CSE) [25]. Using a heavy chain αMHC promoter in coordination with the cystathionine (Cth) gene sequence (responsible for CSE production), a cardiac specific transgene mouse was created to constitutively overexpress the CSE enzyme. These mice had a significantly elevated production rate of H2S, as expected, and were subjected to a similar MI/R protocol. Following 45 minutes of ischemia and 72 hours of reperfusion, the transgenic mice expressed significantly reduced infarct size compared to the wild-type group. These findings reveal that both exogenous donors and endogenously elevated H2S serve to protect against ischemia-reperfusion injury in the murine heart.

The mechanisms by which H2S protected against MI/R injury, we found, are through preservation of mitochondrial function, reduction of cardiomyocyte apoptosis, anti-inflammatory responses, and antioxidant effects that limit cell damage and death. Mitochondria are essential for cell survival and energy production. They are unique in that they regulate cell death and apoptosis and maintain oxidative phosphorylation following MI in a manner that helps to preserve myocyte survival [26]. In vitro experiments revealed a dose-dependent reduction in oxygen consumption followed by a recovery to baseline levels in the H2S treated group [25]. Additionally, H2S at the time of reperfusion preserved function as noted by increases in efficiency of complexes I and II of the electron transport chain. In an ischemia setting, mitochondrial function can be compromised as a result of an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can lead to uncoupling and increased infarction [27, 28]. High doses of H2S can slow down cellular respiration by inhibiting cytochrome c oxidase, lowering metabolism into a protected, preconditioned state [29]. The inhibition of respiration has been shown to protect against MI/R injury by limiting the generation of ROS species [30, 31].

We also found H2S to have antioxidant properties mediated by Nrf-2 signaling. Nrf-2 is a potent antioxidant transcription factor that can translocate from the cytosol to the nucleus to induce various antioxidant proteins. This protein promotes oxidant defenses and reduces oxidative stress. When mice were treated with a long acting H2S donor, diallyl trisulfide (DATS), following acute MI, Nrf-2 translocated from the cytosol to the nucleus while overall levels of Nrf2 remained constant within the cell [32]. Additional studies further demonstrate the downstream signaling of Nrf2 induced by H2S to promote antioxidant defenses [33–36]. These cardioprotective actions, we believed, would also prove to be protective in other heart diseases. We then investigated H2S in heart failure.

4. Hydrogen Sulfide and Heart Failure

Heart failure is the heart's inability to sufficiently supply blood to meet the needs of the body. In the United States, it has become the most common discharge diagnosis in patients 65 years or older and treatments remain insufficient [37, 38]. Therefore, the investigation of therapeutic options to attenuate cardiac dysfunction in heart failure remains clinically relevant and critical.

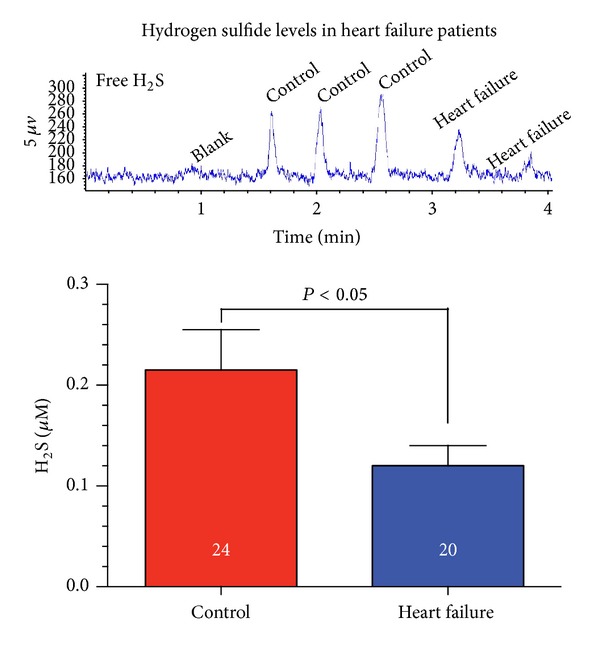

Our group found that heart failure patients have marked reductions in circulating H2S levels compared to age matched controls (Figure 2). In a recent study, Peter et al. reported elevated plasma H2S levels in patients with vascular disease [39]. The results in this study do not contradict our findings of reduced H2S in heart failure patients. The patient profiles in the two studies are dissimilar and do not represent similar disease states. The heart failure patients analyzed in the current study suffer from severe end stage cardiomyopathy with reduced heart function [40]. Conversely, patients in the recent study suffered from coronary or peripheral arterial disease. We do not take these findings as conflicting but acknowledge that changes in H2S are dependent on numerous factors, such as the type of cardiovascular disease (i.e., coronary heart disease or heart failure). The discovery of H2S deficiency in heart failure patients led to our exploration of H2S therapy for the treatment of heart failure. In our preliminary study to create a heart failure in the murine heart, transverse aortic constriction (TAC) between the brachiocephalic trunk and the left carotid artery produced a hypertrophic, pressure overload induced model [20]. We observed greater than a 60% decrease in both myocardial and circulating H2S levels following TAC compared to naïve mice. This finding was in accordance with our discovery that heart failure patients have a H2S deficiency. We next compared mice devoid of the CSE enzyme to wild type mice following TAC. CSE KO mice exhibited significantly greater cardiac dilatation and exacerbated dysfunction than wild-type mice, indicating the demand of H2S to protect against pressure overload heart failure. We then examined H2S therapy in the setting of heart failure. SG-1002, an H2S donor, was infused in the chow and was continuously administered throughout the study beginning the day of aortic constriction. Interestingly, the therapy prevented cardiac dilatation and preserved LV function throughout the 12-week course of the study. Morphological analysis after TAC revealed that H2S treated mice had minor cardiac enlargement compared to the vehicle group, indicating reduced hypertrophy. Similar analysis displayed less pulmonary edema in the H2S treated group.

Figure 2.

Circulating hydrogen sulfide levels are diminished in heart failure patients. We evaluated H2S levels in heart failure patients (n = 24) compared to age-matched control subjects (n = 20). Serum free H2S (μM) levels were significantly reduced (P < 0.05) in heart failure patients. Serum samples were obtained from patients enrolled in the Atlanta Cardiomyopathy Consortium (TACC). This prospective cohort study enrolls patients from the Emory University-affiliated teaching hospitals, the Emory University Hospital and Emory University Hospital Midtown, and Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta. All patients undergo detailed medical history surveys, electrocardiogram, standardized questionnaires, and blood and urine sample collection at baseline. All patients provide written informed consent prior to enrollment. The Emory University Institutional Review Board has approved this study. H2S levels were measured in the blood according to previously described methods [20].

In addition to its antioxidant actions and mitochondrial protection, H2S appears to promote angiogenic responses and inhibit fibrosis during heart failure. Histological analysis revealed that left ventricular intermuscular and perivascular fibrosis were significantly attenuated at 6 weeks following TAC in the H2S treated group [41]. Mice treated with H2S donors in the setting of heart failure also displayed significantly greater VEGF (a potent angiogenic cytokine) and CD31+ (an endothelial cell marker) expression in the myocardium.

Other studies have concurred that the downregulation of H2S is involved in the pathogenesis of cardiomyopathy induced by Adriamycin [42] and myocardial injury induced by isoproterenol [43]. In these studies, myocardial injury resulted in decreased CSE activity, reduced heart and plasma H2S levels, and increased oxidative stress. However, total CSE gene expression was elevated in the heart failure models. These findings were in accordance with our pressure overload induced heart failure model where we observed a robust CSE protein expression but a significant decrease in blood and myocardial H2S levels compared to sham mice [20].

5. Mechanisms of Cardioprotection

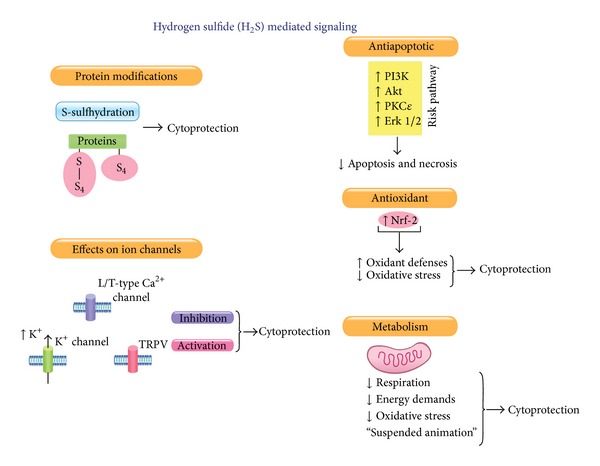

Many of the cardioprotective mechanisms resulting from H2S therapy in acute MI and congestive heart failure are similar (Figure 3). For example, H2S promotes the translocation of the nuclear transcription factor, Nrf2, from the cytosol to the nucleus resulting in the subsequent expression of numerous detoxifying genes such as heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1), superoxide dismutase, and catalase [44, 45]. In addition, H2S protects cells against oxidative stress by increasing glutathione levels in a cysteine dependent manner [46]. Although H2S acts independently to activate antioxidant and prosurvival signals, crosstalk between H2S and NO may also play an important role [21, 47]. H2S is known to activate endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and augment NO bioavailability [20, 41]. NO is well established as a signaling molecule with antioxidant characteristics [48, 49] and may enhance these protective signaling actions.

Figure 3.

Hydrogen sulfide cardioprotective signaling. H2S is known to modify proteins (s-sulfhydration), to modify the function of various ion channels (i.e., Ca2+, K+, and TRPV), to mitigate apoptosis and oxidative stress, and to be a potent modulator of cellular metabolism.

H2S also plays a critical role in the protection of mitochondria during ischemic states in a manner that significantly attenuates cell death and apoptosis [26, 50]. Following MI/R injury, H2S treated mice exhibited diminished activation of caspase-3 and a decreased TUNEL positive nuclei count [25]. H2S also promotes antiapoptotic signaling pathways by altering p38, Erk 1/2, and PI3K expression [51, 52]. Acutely, H2S attenuates mitochondrial respiration to induce a “suspended-animation-” like state and reduces cellular respiration and oxygen demand [29, 53]. Establishing this state can preserve mitochondrial function by reducing oxidative stress and mitigating apoptotic signaling. This renders H2S particularly protective against myocyte injury in settings such as acute MI/R.

One of the earliest proposed benefits of H2S as a physiological modulator on the vasculature is its ability to prevent inflammation [6, 7, 54]. H2S prevents leukocyte adhesion to the vessel wall and inhibits the expression of adhesion molecules [55]. Moreover, in naïve animals, H2S has promoted vessel growth and suppressed antiangiogenic factors [56, 57]. H2S has also been shown to decelerate the progression of cardiac remodeling and promote angiogenesis in a congestive heart failure [20, 41]. Angiogenesis is a complex biological process that involves extracellular matrix remodeling and endothelial growth, migration, and assembly into capillary structures [58]. Decompensated heart failure is associated with a decline in vascular growth and reduced blood flow [57], so H2S may be an attractive therapeutic option for the treatment of the progression of heart failure.

6. Future Directions

A number of laboratories have clearly demonstrated the cardioprotective actions of H2S in both acute myocardial infarction and heart failure [59–62]. The mechanisms responsible for these protective effects include the downregulation of oxidative stress responses, modulation of mitochondrial respiration, attenuation of apoptosis, and increasing vascular growth and angiogenesis. H2S is known to activate multiple and diverse pathways simultaneously and exhibits cross-talk with the NO and CO signal pathways to amplify a cytoprotection response. In addition, H2S freely circulates throughout the body, diffuses across cellular membranes, and acts on multiple cellular targets [63]. Furthermore, the actions of H2S are not limited to the heart muscle alone but can impact the entire cardiovascular system including blood vessels [7]. In fact, with this field only recently developing, there are tremendous opportunities for further discovery relating to H2S physiology, pharmacology, and pathology. Recent experimental data provide evidence that H2S can prevent atherosclerosis and promotes angiogenesis in the peripheral arteries [55, 64]. This may prove beneficial when treating vascular diseases that demand collateral vessel growth such as peripheral artery disease (PAD) and critical limb ischemia (CLI). Recently, several groups have reported that H2S also plays a role in pulmonary hypertension and acute lung injury [65, 66]. Although H2S does not have the potent vasodilation capabilities of NO, the combination of vascular smooth muscle relaxation and potent antioxidant properties may be the source for protection against pulmonary hypoxia and hypertension. In both the liver and the kidneys, H2S is a protective preconditioning agent against ischemia/reperfusion injury [67, 68]. Similarly to myocardial ischemia/reperfusion protection, H2S protects by its ability to mitigate apoptosis and modulate oxidative stress.

Discovering the most effective H2S donors is also a challenge facing the field. Drugs such as NaHS, Na2S, and GYY4137 are all effective H2S donors, but their rapid half-life renders them less effective for treating chronic diseases. The slow releasing polysulfides deliver a more gradual release of H2S [32]. Other proposed sulfide-modulating agents such as S-propargyl-cysteine do not substantially raise H2S levels in vivo [69]. Dietary formulations, such as SG-1002, can be used as medical foods to replenish an H2S deficiency that may occur from diseases such as heart failure. Because of the short half-life of H2S (estimated to be between seconds and minutes [17, 70]), developing a drug with specific on-site (organ or organelle specific) delivery would also be beneficial.

Following in the footsteps of nitric oxide and carbon monoxide, hydrogen sulfide is rapidly emerging as a critical cardiovascular signaling molecule. Although the complete actions of this gas remain under investigation, the therapeutic options relating to cardiovascular disease are extremely promising. The coming years or research will dictate the means of utilizing this molecule effectively against various cardiovascular disease states.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank The Atlanta Cardiomyopathy Consortium (TACC) for generously providing blood samples from heart failure patients for the measurement of hydrogen sulfide. This work was supported by Grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (National Institutes of Health; 1R01 HL092141, 1R01 HL093579, 1U24 HL 094373, and 1P20 HL113452 to David J. Lefer). The authors are also grateful for the generous funding support from TEVA USA Scholars Program and the LSU Medical School Alumni Association.

Conflict of Interests

David J. Lefer is a founder of the company Sulfagenix and has significant stock in Sulfagenix. David J. Lefer is also the Chief Scientific Officer for Sulfagenix. Sulfagenix is currently developing hydrogen sulfide (H2S) based therapeutics for the treatment of cardiovascular and other diseases. There are no other conflicts.

References

- 1.Ramazzini B. De morbis artificum diatriba [diseases of workers]. 1713. The American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(9):1380–1382. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.9.1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abe K, Kimura H. The possible role of hydrogen sulfide as an endogenous neuromodulator. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16(3):1066–1071. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-03-01066.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang R. Physiological implications of hydrogen sulfide: a whiff exploration that blossomed. Physiological Reviews. 2012;92(2):791–896. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00017.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan MV, Wallace JL. Hydrogen sulfide-based therapeutics and gastrointestinal diseases: translating physiology to treatments. The American Journal of Physiology—Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 2013;305(7):G467–G473. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00169.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fiorucci S, Antonelli E, Distrutti E, et al. Inhibition of hydrogen sulfide generation contributes to gastric injury caused by anti-inflammatory nonsteroidal drugs. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(4):1210–1224. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fiorucci S, Distrutti E, Cirino G, Wallace JL. The emerging roles of hydrogen sulfide in the gastrointestinal tract and liver. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(1):259–271. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zanardo RCO, Brancaleone V, Distrutti E, Fiorucci S, Cirino G, Wallace JL. Hydrogen sulfide is an endogenous modulator of leukocyte-mediated inflammation. The FASEB Journal. 2006;20(12):2118–2120. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6270fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barañano DE, Snyder SH. Neural roles for heme oxygenase: contrasts to nitric oxide synthase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(20):10996–11002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191351298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elrod JW, Duranski MR, Langston W, et al. eNOS gene therapy exacerbates hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury in diabetes: a role for enos uncoupling. Circulation Research. 2006;99(1):78–85. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000231306.03510.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pryor WA, Houk KN, Foote CS, et al. Free radical biology and medicine: it’s a gas, man! The American Journal of Physiology—Regulatory Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2006;291(3):R491–R511. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00614.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bolli R. Cardioprotective function of inducible nitric oxide synthase and role of nitric oxide in myocardial ischemia and preconditioning: an overview of a decade of research. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2001;33(11):1897–1918. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Bartley DA, Uhl GR, Snyder SH. Mechanisms of nitric oxide-mediated neurotoxicity in primary brain cultures. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1993;13(6):2651–2661. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-06-02651.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dawson TM, Snyder SH. Gases as biological messengers: nitric oxide and carbon monoxide in the brain. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14(9):5147–5159. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-09-05147.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark JE, Naughton P, Shurey S, et al. Cardioprotective actions by a water-soluble carbon monoxide-releasing molecule. Circulation Research. 2003;93:e2–e8. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000084381.86567.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamoun P. Endogenous production of hydrogen sulfide in mammals. Amino Acids. 2004;26(3):243–254. doi: 10.1007/s00726-004-0072-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Polhemus DJ, Lefer DJ. Emergence of hydrogen sulfide as an endogenous gaseous signaling molecule in cardiovascular disease. Circulation Research. 2014;114(4):730–737. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.300505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang R. Two’s company, three’s a crowd: can H2S be the third endogenous gaseous transmitter? The FASEB Journal. 2002;16(13):1792–1798. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0211hyp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boehning D, Snyder SH. Novel neural modulators. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2003;26:105–131. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.041002.131047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shibuya N, Tanaka M, Yoshida M, et al. 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase produces hydrogen sulfide and bound sulfane sulfur in the brain. Antioxidants and Redox Signaling. 2009;11(4):703–714. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kondo K, Bhushan S, King AL, et al. H2S protects against pressure overload-induced heart failure via upregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Circulation. 2013;127(10):1116–1127. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.King AL, Polhemus DJ, Bhushan S, et al. Hydrogen sulfide cytoprotective signaling is endothelial nitric oxide synthase-nitric oxide dependent. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111(8):3182–3187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321871111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murray CJL, Lopez AD. Mortality by cause for eight regions of the world: Global Burden of Disease Study. The Lancet. 1997;349(9061):1269–1276. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07493-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haffner SM, Lehto S, Rönnemaa T, Pyörälä K, Laakso M. Mortality from coronary heart disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes and in nondiabetic subjects with and without prior myocardial infarction. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;339(4):229–234. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807233390404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dhalla NS, Elmoselhi AB, Hata T, Makino N. Status of myocardial antioxidants in ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cardiovascular Research. 2000;47(3):446–456. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00078-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elrod JW, Calvert JW, Morrison J, et al. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by preservation of mitochondrial function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(39):15560–15565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705891104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murphy E, Steenbergen C. Preconditioning: the mitochondrial connection. Annual Review of Physiology. 2007;69:51–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.031905.163645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zamzami N, Marchetti P, Castedo M, et al. Sequential reduction of mitochondrial transmembrane potential and generation of reactive oxygen species in early programmed cell death. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1995;182(2):367–377. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.2.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Becker LB. New concepts in reactive oxygen species and cardiovascular reperfusion physiology. Cardiovascular Research. 2004;61(3):461–470. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blackstone E, Morrison M, Roth MB. H2S induces a suspended animation-like state in mice. Science. 2005;308(5721):p. 518. doi: 10.1126/science.1108581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen Q, Camara AKS, Stowe DF, Hoppel CL, Lesnefsky EJ. Modulation of electron transport protects cardiac mitochondria and decreases myocardial injury during ischemia and reperfusion. The American Journal of Physiology—Cell Physiology. 2007;292(1):C137–C147. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00270.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Q, Moghaddas S, Hoppel CL, Lesnefsky EJ. Reversible blockade of electron transport during ischemia protects mitochondria and decreases myocardial injury following reperfusion. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2006;319(3):1405–1412. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.110262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Predmore BL, Kondo K, Bhushan S, et al. The polysulfide diallyl trisulfide protects the ischemic myocardium by preservation of endogenous hydrogen sulfide and increasing nitric oxide bioavailability. The American Journal of Physiology—Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2012;302(11):H2410–H2418. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00044.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen C, Pung D, Leong V, et al. Induction of detoxifying enzymes by garlic organosulfur compounds through transcription factor Nrf2: effect of chemical structure and stress signals. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2004;37(10):1578–1590. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fukao T, Hosono T, Misawa S, Seki T, Ariga T. The effects of allyl sulfides on the induction of phase II detoxification enzymes and liver injury by carbon tetrachloride. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2004;42(5):743–749. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu C, Lii C, Tsai S, Sheen L. Diallyl trisulfide modulates cell viability and the antioxidation and detoxification systems of rat primary hepatocytes. Journal of Nutrition. 2004;134(4):724–728. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.4.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zeng T, Zhang C, Zhu Z, Yu L, Zhao X, Xie K. Diallyl trisulfide (DATS) effectively attenuated oxidative stress-mediated liver injury and hepatic mitochondrial dysfunction in acute ethanol-exposed mice. Toxicology. 2008;252(1–3):86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2008.07.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Foo RS-Y, Mani K, Kitsis RN. Death begets failure in the heart. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2005;115(3):565–571. doi: 10.1172/JCI24569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cohen-Solal A, Beauvais F, Logeart D. Heart failure and diabetes mellitus: epidemiology and management of an alarming association. Journal of Cardiac Failure. 2008;14(7):615–625. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peter EA, Shen X, Shah SH, et al. Plasma free H2S levels are elevated in patients with cardiovascular disease. The American Heart Association. 2013;2(5) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000387.e000387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bhushan S, Kondo K, Polhemus DJ, et al. Nitrite therapy improves left ventricular function during heart failure via restoration of nitric oxide-mediated cytoprotective signaling. Circulation Research. 2014;114(8):1281–1291. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.301475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Polhemus DJ, Kondo K, Bhushan S, et al. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates cardiac dysfunction after heart failure via induction of angiogenesis. Circulation: Heart Failure. 2013;6(5):1077–1086. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Su Y, Liang C, Jin H, et al. Hydrogen sulfide regulates cardiac function and structure in adriamycin-induced cardiomyopathy. Circulation Journal. 2009;73(4):741–749. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-08-0636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Geng B, Chang L, Pan C, et al. Endogenous hydrogen sulfide regulation of myocardial injury induced by isoproterenol. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2004;318(3):756–763. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Motohashi H, Yamamoto M. Nrf2-Keap1 defines a physiologically important stress response mechanism. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2004;10(11):549–557. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chan K, Han X, Kan YW. An important function of Nrf2 in combating oxidative stress: detoxification of acetaminophen. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(8):4611–4616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081082098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kimura Y, Kimura H. Hydrogen sulfide protects neurons from oxidative stress. The FASEB Journal. 2004;18(10):1165–1167. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1815fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hosoki R, Matsuki N, Kimura H. The possible role of hydrogen sulfide as an endogenous smooth muscle relaxant in synergy with nitric oxide. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1997;237(3):527–531. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kanner J, Harel S, Granit R. Nitric oxide as an antioxidant. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1991;289(1):130–136. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(91)90452-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.del Río LA, Corpas FJ, Sandalio LM, Palma JM, Gómez M, Barroso JB. Reactive oxygen species, antioxidant systems and nitric oxide in peroxisomes. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2002;53(372):1255–1272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nicholson CK, Calvert JW. Hydrogen sulfide and ischemia-reperfusion injury. Pharmacological Research. 2010;62(4):289–297. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cai W, Wang M, Moore PK, Jin H, Yao T, Zhu Y. The novel proangiogenic effect of hydrogen sulfide is dependent on Akt phosphorylation. Cardiovascular Research. 2007;76(1):29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hu Y, Chen X, Pan T, et al. Cardioprotection induced by hydrogen sulfide preconditioning involves activation of ERK and PI3K/Akt pathways. Pflugers Archiv European Journal of Physiology. 2008;455(4):607–616. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0321-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Blackstone E, Roth MB. Suspended animation-like state protects mice from lethal hypoxia. Shock. 2007;27(4):370–372. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31802e27a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gadalla MM, Snyder SH. Hydrogen sulfide as a gasotransmitter. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2010;113(1):14–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06580.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang Y, Zhao X, Jin H, et al. Role of hydrogen sulfide in the development of atherosclerotic lesions in apolipoprotein e knockout mice. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2009;29(2):173–179. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.179333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Coletta C, Papapetropoulos A, Erdelyi K, et al. Hydrogen sulfide and nitric oxide are mutually dependent in the regulation of angiogenesis and endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109(23):9161–9166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202916109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Izumiya Y, Shiojima I, Sato K, Sawyer DB, Colucci WS, Walsh K. Vascular endothelial growth factor blockade promotes the transition from compensatory cardiac hypertrophy to failure in response to pressure overload. Hypertension. 2006;47(5):887–893. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000215207.54689.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carmeliet P. Angiogenesis in health and disease. Nature Medicine. 2003;9(6):653–660. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Calvert JW, Elston M, Nicholson CK, et al. Genetic and pharmacologic hydrogen sulfide therapy attenuates ischemia-induced heart failure in mice. Circulation. 2010;122(1):11–19. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.920991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sivarajah A, McDonald MC, Thiemermann C. The production of hydrogen sulfide limits myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury and contributes to the cardioprotective effects of preconditioning with endotoxin, but not ischemia in the rat. Shock. 2006;26(2):154–161. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000225722.56681.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Johansen D, Ytrehus K, Baxter GF. Exogenous hydrogen sulfide (H2S) protects against regional myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Evidence for a role of KATP channels. Basic Research in Cardiology. 2006;101(1):53–60. doi: 10.1007/s00395-005-0569-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang X, Wang Q, Guo W, Zhu YZ. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates cardiac dysfunction in a rat model of heart failure: a mechanism through cardiac mitochondrial protection. Bioscience Reports. 2011;31(2):87–98. doi: 10.1042/BSR20100003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang R. The gasotransmitter role of hydrogen sulfide. Antioxidants and Redox Signaling. 2003;5(4):493–501. doi: 10.1089/152308603768295249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang M, Cai W, Li N, Ding Y, Chen Y, Zhu Y. The hydrogen sulfide donor NaHS promotes angiogenesis in a rat model of hind limb ischemia. Antioxidants and Redox Signaling. 2010;12(9):1065–1077. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang C, Du J, Bu D, Yan H, Tang X, Tang C. The regulatory effect of hydrogen sulfide on hypoxic pulmonary hypertension in rats. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2003;302(4):810–816. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00256-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Esechie A, Kiss L, Olah G, et al. Protective effect of hydrogen sulfide in a murine model of acute lung injury induced by combined burn and smoke inhalation. Clinical Science. 2008;115(3-4):91–97. doi: 10.1042/CS20080021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jha S, Calvert JW, Duranski MR, Ramachandran A, Lefer DJ. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury: role of antioxidant and antiapoptotic signaling. The American Journal of Physiology—Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2008;295(2):H801–H806. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00377.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bos EM, Leuvenink HGD, Snijder PM, et al. Hydrogen sulfide-induced hypometabolism prevents renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2009;20(9):1901–1905. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008121269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gong Q, Wang Q, Pan L, Liu X, Xin H, Zhu Y. S-propargyl-cysteine, a novel hydrogen sulfide-modulated agent, attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced spatial learning and memory impairment: involvement of TNF signaling and NF-κB pathway in rats. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2011;25(1):110–119. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Insko MA, Deckwerth TL, Hill P, Toombs CF, Szabo C. Detection of exhaled hydrogen sulphide gas in rats exposed to intravenous sodium sulphide. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2009;157(6):944–951. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00248.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ward P. Impact from the deep. Scientific American. 2006;295:64–71. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican1006-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Savage JC, Gould DH. Determination of sulfides in brain tissue and rumen fluid by ion-interaction reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. Journal of Chromatography. 1990;526:540–545. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)82537-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Goodwin LR, Francom D, Dieken FP, et al. Determination of sulfide in the brain tissue by gas dialysis/ion chromatography: postmortem studies and two case reports. Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 1989;13:105–109. doi: 10.1093/jat/13.2.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Warenycia MW, Steele JA, Karpinski E, Reiffenstein RJ. Hydrogen sulfide in combination with taurine or cysteic acid reversibly abolishes sodium currents in neuroblastoma cells. Neurotoxicology. 1989;10:191–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mustafa AK, Gadalla MM, Sen N, et al. H2S signals through protein S-sulfhydration. Science Signaling. 2009;2(article ra72) doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]