Introduction

On an egg-by-egg basis, normal human reproduction is an inefficient process. The indirect methods to determine this suggest that only about every fourth or fifth egg-sperm interaction results in a live birth (Wilcox et al., 1985; Zinaman et al., 1985). This is, of course, an average estimate and depends on many variables, the principal one of which is age.

A 21st century study (Wang et al., 2003) calculated that among 441 subjects who averaged 24.9 years of age there was only a 30.1% chance of having a term pregnancy on the first exposure, even when explicitly trying to get pregnant.

In vivo in the human, there is no possibility to examine material from loss at the early cleavage stages. A majority of the failures seem to occur at this early stage. However, material has been studied from early clinical pregnancy losses. In one study, abnormalities were demonstrated at the chromosome level in approximately two-thirds of the specimens (Lathi et al., 2008). Another large study comparing aneuploidy in spontaneous loss vs loss after ART found 55.14% abnormalities from spontaneous and 51.88% after ART (Martinez et al., 2010).

While normal human reproduction seems to be quite inefficient, on an egg-by-egg basis reproduction by in vitro fertilization seems to be even more inefficient.

Reproductive efficiency of human eggs fertilized in vitro on an egg-to-egg basis is a seldom used evaluation of clinical assisted reproductive technology.

However, there have been a number of studies on this point (Inge et al., 2005; Meniru and Craft, 1997; Patrizio et al., 2007). It seems that only about 5% of harvested mature oocytes produce a live baby.

The purposes of this study are to determine if our own data confirm previous studies on the efficiency of eggs fertilized in vitro, to compare the inefficiency of normal human reproduction with the inefficiency of clinical IVF on an egg basis and to point out the implications of these inefficiencies.

Methods and Materials

Fifty-nine thousand nine hundred and forty oocytes considered mature immediately after aspiration are included (Table I). The word “mature” is used because in some instances, especially in the early years, a polar body was not specifically identified before the introduction of sperm.

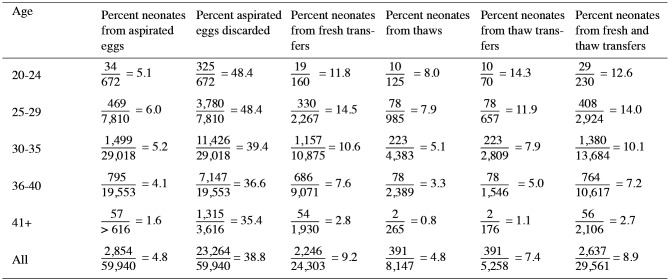

Table II. Percentage utilization by age of 59,940 oocytes fertilized in vitro.

Table I. Characteristics for severe PPGP.

| Age | Total mature aspirated | Total mature transferred | Total mature frozen | Total mature discarded | Total mature thawed | Thawed transferred | Thawed discarded | Still frozen | Neonates Fresh | Neonates thawed | Estimated Neonates still frozen | Total neonates |

| 20-24 | 672 | 160 | 187 | 325 | 125 | 70 | 55 | 62 | 19 | 10 | 5 | 34 |

| 25-29 | 7,810 | 2,267 | 1,763 | 3,780 | 985 | 657 | 328 | 778 | 330 | 78 | 61 | 69 |

| 30-35 | 29,018 | 10,875 | 6,717 | 11,426 | 4,383 | 2,809 | 1,474 | 2,334 | 1,157 | 223 | 119 | 1,499 |

| 36-40 | 19,553 | 9,071 | 3,335 | 7,147 | 2,389 | 1,546 | 843 | 945 | 686 | 78 | 31 | 795 |

| 41+ | 3,616 | 1,930 | 371 | 1,315 | 265 | 176 | 89 | 106 | 54 | 2 | 1 | 57 |

| All | 59,940 | 24,303 | 12,373 | 23,264 | 8,147 | 5,258 | 2,889 | 4,226 | 2,246 | 391 | 217 | 2,854 |

These were collected during the years from 1981-2008. Donor eggs and offsite affiliated cases are not included. Conventional in vitro fertilization and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) are included.

Follow-up is as reported by the patient shortly after birth and is thought to be essentially complete. Neonates as a percent of eggs after various steps in the IVF procedure are tabulated (Table II).

Results

Overall, 4.8% of aspirated mature eggs resulted in a live born neonate. After age 40, this figure drops to 1.6% (Table II).

Some 38.8% of aspirated eggs were discarded. To age 30, the discard figure approximated 50% and declines in older age brackets (Table II).

Overall, 9.2% of freshly transferred fertilized eggs resulted in a live neonate. This figure dropped to 7.4% for thaw transfers (Table 2). In both fresh and thawed transfers, there is a fall in the efficiency on an egg-to-egg basis with increasing age beginning at age 25 (Table II).

A combination of fresh plus thaw transfers yielded an 8.9% egg efficiency with the greatest efficiency of 14% being in the age group of 25-30 (Table 2).

Cryopreservation per se resulted in a loss of 35.5% of the eggs which had become fertilized (Table 1). Some of these may have been intentionally discarded or transferred to another program.

Discussion

If we accept the efficiency of normal human reproduction at age 25 as 30.1% as determined by a very recent study (Wang X, et al., 2003) and use the IVF efficiency from this study for the age group 25-29 as 6.0% it can be concluded that IVF is only about one-fifth as efficient as normal human reproduction which is itself quite inefficient on an egg-to-egg basis.

There are several possible reasons for this.

On average, eggs after stimulation may have less pregnancy potential than the single egg of the normal cycle. During 1981, with very gentle stimulation, there were 48 eggs collected and seven term pregnancies (and no miscarriages) for an egg efficiency of 14.6%. With time and the use of controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH), the pregnancy rate per cycle has increased but the egg efficiency rate has decreased. This point was previously made in a study by Meniru and Craft (Meniu G, Craft I, 1997). This possible decrease with greater stimulation raises the question of whether the greater stimulation concept should be reexamined, especially in low responders.

To be sure, some IVF egg inefficiency may be associated with the intrinsic egg problems causing the infertility. This is probably a minor difficulty when the infertility is due to a mechanical problem, as for instance, in the blocked fallopian tubes. However, it is probably much more significant in the unexplained category.

The incidence of discard eggs is of interest. Overall, this amounted to 38.8% (Table II). For the most part, discards are on a morphological basis with a presumption that such discards do not have pregnancy potential. If we accept that only one in four eggs in normal reproduction has pregnancy potential, the discard rate should be even higher than it is. These data can be taken as evidence of a concept long recognized, namely, that morphology is only a relative help in determining exact normality. It is of interest that the discard rate decreased with age when it really should be the opposite. This probably represents a certain bias on the part of the observer to try to increase the number of available eggs to older patients.

Cryopreservation per se resulted in a discard rate of 35.5%. The remaining cryopreserved eggs (now embryos) proved to be somewhat less efficient than for fresh eggs (now embryos) as judged by neonates after transfer. Overall, the thaw transfer neonate rate of 7.4% was about 20% lower than the 9.2% rate for fresh transfers.

The embryo-endometrium relationship has been of interest and concern since the early days of IVF. Many studies have demonstrated a window of implantation (Nikas et al., 2000). Studies with evolving techniques have demonstrated variations from normal in the endometrium from patients subject to COH (Haouzi et al., 2009). However, a convincing demonstration that these variations are a major cause of lack of implantation after IVF remains elusive. Indeed, a recent study of this situation in patients undergoing preimplantation genetic screening (PGS) because of advanced age and other causes led the author to include in the title, “it is in the seed and not the soil” that was a major cause of the inefficiency of IVF (Patrizio, 2007). This does not mean that continuing investigation of the endometrial situation is not warranted, but it does mean that the principal research effort is more likely to be productive if it is devoted to the identity and improvement of the pregnancy potential of the fertilized egg.

Conclusion

On an egg-to-egg basis, IVF is about one-fifth as efficient as normal reproduction, which is itself quite inefficient. Some one-third of fertilized eggs were lost by cryopreservation per se. Surviving thawed fertilized eggs were also about 20% less efficient than fresh eggs in producing a live neonate. Gentle stimulation, although producing fewer eggs, produced a higher percent of eggs which resulted in live neonates.

References

- Haouzi D, Assou S, Mahmoud K, et al. Gene expression profile of human endometrial receptivity: comparison between natural and simulated cycles for the same patients. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:1436–1445. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inge GB, Brinsden PR, Elder KT. Oocyte number per live birth in IVF: were Steptoe and Edwards less wasteful? Hum Reprod. 2005;20:588–592. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lathi RB, Westphal LM, Milki AA. Aneuplooidy in the miscarriages of infertile women and the potential benefit of preimplantation genetic diagnosis. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:353–357. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez MC, Mendez C, Ferro J, et al. Cytogenetic analysis of early nonviable pregnancies after assisted reproduction treatment. Fertil Steril. 2010;93:289–292. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.07.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meniru GI, Craft IL. Utilization of retrieved oocytes as an index of the efficiency of superovulation strategies for in-vitro fertilization treatment. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:2129–2132. doi: 10.1093/humrep/12.10.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikas G, Makrigiannakis A, Hovatta O, et al. Surface morphology of the human endometrium. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;900:316–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrizio P, Bianchi V, Lalioti M, et al. High rate of biological loss in assisted reproduction: it is in the seed, not in the soil. Reprod Biomed Online. 2007;14:92–95. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60769-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Chen C, Wang L, et al. Conception, early pregnancy loss, and time to clinical pregnancy: a population-based prospective study. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:577–584. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)04694-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, Wehmann RE, et al. Measuring early pregnancy loss: laboratory and field methods. Fertil Steril. 1984;44:366–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinaman MJ, Connor J, Cleg ED, et al. Estimates of human fertility and pregnancy loss. Fertil Steril. 1996;65:503–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]