Abstract

Background:

The SHIVA trial is a multicentric randomised proof-of-concept phase II trial comparing molecularly targeted therapy based on tumour molecular profiling vs conventional therapy in patients with any type of refractory cancer. Results of the feasibility study on the first 100 enrolled patients are presented.

Methods:

Adult patients with any type of metastatic cancer who failed standard therapy were eligible for the study. The molecular profile was performed on a mandatory biopsy, and included mutations and gene copy number alteration analyses using high-throughput technologies, as well as the determination of oestrogen, progesterone, and androgen receptors by immunohistochemistry (IHC).

Results:

Biopsy was safely performed in 95 of the first 100 included patients. Median time between the biopsy and the therapeutic decision taken during a weekly molecular biology board was 26 days. Mutations, gene copy number alterations, and IHC analyses were successful in 63 (66%), 65 (68%), and 87 (92%) patients, respectively. A druggable molecular abnormality was present in 38 patients (40%).

Conclusions:

The establishment of a comprehensive tumour molecular profile was safe, feasible, and compatible with clinical practice in refractory cancer patients.

Keywords: feasibility, molecular profile, personalised medicine, randomised study, SHIVA, sequencing

As opposed to cytotoxic agents, molecularly targeted agents (MTAs) are supposed to produce antitumour activity only in the presence of their target(s). Although the targets of these agents are usually well known, a substantial proportion of MTAs lack a validated predictive biomarker of efficacy, such as antiangiogenic agents or mammalian Target Of Rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors. The clinical development of MTAs has been primarily performed according to the primary location and the histology, and in some instances within a subgroup of patients defined by molecular characteristics.

Two recent studies have suggested that selecting MTAs based on the molecular profile of the patients' tumour independently of tumour location and histology might improve patient outcome. Von Hoff et al (2010) first published a histology-independent clinical trial using molecular profiling of patients' tumour to select treatment. Patients with refractory advanced cancer had their tumour samples analysed using immunohistochemistry (IHC), fluorescent in situ hybridization assays, and oligonucleotide microarray gene expression assays. A drug or drug combination was suggested based on the results of the molecular profile. In all, 18 of the 66 evaluable patients (27%) had a progression-free survival (PFS) ratio (PFS on study divided by PFS on prior treatment) of >1.3. Similar conclusions were reported in patients referred for a phase I trial at the MD Anderson Cancer Center who underwent a tumour biopsy of a metastasis to assess specific molecular alterations (Tsimberidou et al, 2012). In addition, the outcome of patients who entered a phase I trial based on a molecular abnormality was better than the outcome of patients who entered a trial without matching. However, the lack of randomization vs standard of care in these studies did not allow robust conclusions (Doroshow, 2010).

We therefore initiated the SHIVA trial (NCT01771458) which is a randomised proof-of-concept phase II trial comparing molecularly targeted therapy based on tumour molecular profiling vs conventional but not standard of care chemotherapy (or best supportive care) in refractory cancer patients. We report here the results of the feasibility part on the first hundred included patients.

Patients and methods

Patient selection

Patients older than 18 years with any type of recurrent and/or metastatic cancer who failed standard therapy were eligible for the study, provided their disease was measurable and accessible for a biopsy/resection of a metastatic site (Le Tourneau et al, 2012). Bone tumour sampling was not allowed. Patients were allowed to receive conventional chemotherapy but no MTA or hormone therapy between the biopsy and the randomization. Patients were required to have an ECOG performance status of 0 or 1, adequate renal, hepatic and bone marrow functions. Patients with brain metastases that were controlled for >3 months were eligible. Anticoagulation with anti-vitamin K was not permitted. Patients with other concurrent severe and/or uncontrolled medical disease that could compromise participation in the study were excluded.

For patients eligible for the randomization, randomization criteria included the identification of tumour molecular abnormalities for which the Molecular Biology Board (MBB) set up for the trial recommended an MTA available in the context of the trial, a left ventricular ejection fraction of >50%, a QTc interval of <480 ms, and preserved ECOG performance status, renal, hepatic and bone marrow functions.

The SHIVA trial was approved by the ethics committee and the French ‘Agence Nationale de Sécurité du Médicament et des Produits de Santé'. The trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent.

Study design

The molecular profile of patient tumour was performed on a mandatory biopsy/resection of a metastasis. If no molecular abnormality for which an approved matched MTA existed in the frame of the SHIVA trial was identified, then patients were not eligible for the randomization and entered into a prospective observational cohort. If one or several molecular abnormalities were identified, then patients were randomised.

To control patient heterogeneity, randomization was stratified according to the signalling pathway relevant for the choice of the MTA and the patient prognosis based on the Royal Marsden Hospital score for oncology phase I trials (Arkenau et al, 2009). Three signalling pathways have arbitrarily been used for stratification: (1) the hormone receptors pathway, (2) the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, and (3) the MAP kinase pathway.

A cross-over was proposed at disease progression for patients in both treatment arms. Quotas were introduced so that no >20% of the randomised patients had the same tumour type. The treating physician was only informed of the result of the molecular abnormality of interest just at the time when the patient was about to start treatment with the matched MTA, being at randomization or at cross-over. The feasibility part of the study involved the first hundred included patients.

Sample collection

At least three tumour samples were required for each patient. One biopsy was fixed and paraffin embedded for diagnostic confirmation, and oestrogen (ER), progesterone (PR), and androgen (AR) receptors expression analyses. The other biopsies were fresh frozen. One of them was used for DNA extraction using the kit Qiagen (Hilden, Germany) after evaluation of tumour cell content on a frozen section. This was performed before extraction to allow microdissection of the sample to increase tumour cellularity. Samples containing ⩾50% of tumour cells were considered suitable for DNA extractions and genomic analyses. The remaining frozen biopsies were used in case of insufficient DNA amount/quality for molecular analyses or otherwise stored for further studies. The extracted tumour DNA was used for mutations and gene copy number analyses.

Mutation analyses

Screening of hotspot mutations was performed by targeted sequencing using the Ion Ampliseq cancer panel V1 in conjunction with the Ampliseq library kit v2.0 and the Ion Torrent Personal Genome Analyzer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) (Supplementary Table 1). Following the manufacturer's instructions, 10 ng of extracted DNA was used to generate 190 amplicons surveying 739 mutations in 46 well-established oncogenes and tumour suppressor genes through optimised multiplex PCR. Extremities of amplicons were partially digested. Ion adapters (Life Technologies), including one with a molecular barcode, were ligated at both ends. After amplification of the construction by PCR, quality of libraries was checked on a BioAnalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) or a Labchip GX (Perkin-Elmer, Alameda, CA, USA) and quantified with Qubit Technology (Life Technologies). Template preparation was performed using the Ion OneTouch System with the Ion OneTouch 200 Template Kit v2 DL (Life Technologies). Templates were sequenced on Ion Torrent PGM with an Ion PGM sequencing kit and the Ion Chips. The overall quality of each run was evaluated based on the report generated by the Torrent Server. At least 100 000 reads were required per sample. A sample was considered to be valuable only if 99% of targeted positions were covered at 1 × , 97% at 20 × , and 95% at 100 × , according to the analysis performed by the variant caller plugin of the Torrent Suite (Life Technologies).

Gene copy number determination

Selected gene copy number alterations (amplification or deletion) were assessed using Cytoscan HD according to the manufacturer's protocol (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Two hundred and fifty nanograms of genomic DNA were employed to conduct the target preparation and hybridised microarrays. When the amount of available genomic DNA was below 250 ng, a first whole genome amplification (Qiagen, REPLI-g Mini Kit PN: 150023) step was implemented to the assay. Negative and positive controls were added in all batches of samples to insure the quality control of analyses (Affymetrix normal DNA).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry technique was used to determine the expression levels of ER, PR, and AR. Expressions of ER, PR, and AR were considered as positive if ⩾10% of tumour cells expressed the receptor. The IHC technique was also used for the validation of the following gene amplifications/deletions detected using Cytoscan HD: PTEN, EGFR, HER2, KIT, MET, ALK, and PDGFRA/B.

Bioinformatics

The Cytoscan HD profiles were analysed and corrected according to cellularity. Gene copy number profiles were first centered on the median, and segmented with the Colibri algorithm (Rigaill, 2010). The detection of gene copy number alterations and loss of heterozygosity status of the tumour were performed with the GLAD (Hupé et al, 2004) and GAP (Popova et al, 2009) algorithms, respectively. Focal amplifications were defined as gene copy number ⩾6 for diploid tumours and ⩾7 for tetraploid tumours and an amplicon size of ⩽1 Mb or ⩽10 Mb if specific protein overexpression was confirmed by IHC. Gene losses were defined as 1 copy for diploid tumours and 1 or 2 copies for tetraploid tumours, whereas gene deletions corresponded to 0 copy.

For mutations analyses, sequencing reads were aligned on the Human reference genome (hg19) using the TMAP software (Life Technologies). The variants were detected using the Variant Caller software (Life Technologies) and annotated using the ANNOVAR pipeline (Wang et al, 2010). The variants were filtered according to their frequency (>4% for SNV and >10% for indels), strand ratio (>0.2), and reads coverage (>30 × for SNV and 100 × for indels).

The Bioinformatics platform integrated the different molecular results in a name-blinded technical report, which was discussed by the MBB.

Molecular Biology Board

The MBB included biologists, physicians, bioinformaticians, the technical platforms' managers, and pathologists. The MBB was in charge of the scientific validation and prioritization of the identified molecular abnormalities.

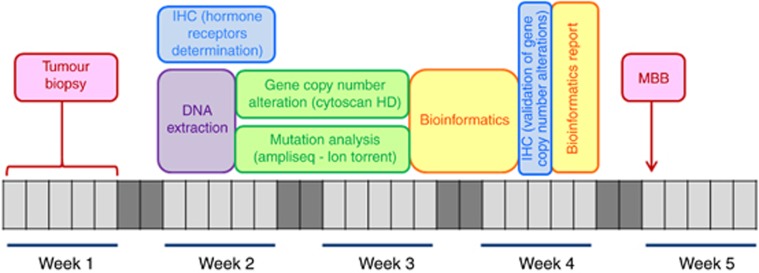

Following the MBB, a final report was validated and signed by the accredited biologists. Previous therapy was taken into account by the physicians for the treatment recommendation. The whole process was set up to have less than 4 weeks elapsed between the biopsy and the day the MBB (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Timelines for the establishment of the tumour molecular profile in the SHIVA trial. IHC=immunohistochemistry; MBB=Molecular Biology Board.

Treatment algorithm

Molecularly targeted agents used in the experimental arm of the SHIVA trial are only drugs that are approved for clinical use in France. Single MTAs were selected following a predefined algorithm (Table 1), except for patients whose tumour harboured a mutation or an amplification of HER2 who were treated with trastuzumab and lapatinib given the overall survival benefit demonstrated in HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer patients (Blackwell et al, 2012). The SHIVA algorithm was set up following several meetings with biologists and researchers and takes into account the few alterations validated in the clinic as well as alterations described in the literature in a preclinical setting.

Table 1. Treatment algorithm in the experimental arm.

| Targets | Molecular abnormalities | Molecularly targeted agents |

|---|---|---|

| KIT, ABL1/2, RET |

Activating mutation or amplificationa |

Imatinib 400 mg qd PO |

| PI3KCA, AKT1 |

Activating mutation or amplification |

Everolimus 10 mg qd PO |

| AKT2,3, mTOR, RAPTOR, RICTOR |

Amplification |

Everolimus 10 mg qd PO |

| PTEN |

Homozygous deletion or heterozygous deletion+inactivating mutation or heterozygous deletion+IHC confirmation |

Everolimus 10 mg qd PO |

| STK11 |

Homozygous deletion or heterozygous deletion+inactivating mutation |

Everolimus 10 mg qd PO |

| INPP4B |

Homozygous deletion |

Everolimus 10 mg qd PO |

| BRAF |

Activating mutation or amplification |

Vemurafenib 960 mg bid PO |

| PDGFRA/B, FLT3 |

Activating mutation or amplification |

Sorafenib 400 mg bid PO |

| EGFR |

Activating mutation or amplification |

Erlotinib 150 mg qd PO |

| ERBB2/HER2 |

Activating mutation or amplification |

Lapatinib 1000 mg qd PO+Trastuzumab 8 mg kg−1 IV followed by 6 mg kg−1 IV q3w |

| SRC |

Activating mutation or amplification |

Dasatinib 70 mg bid PO |

| EPHA2, LCK, YES1 |

Amplification |

Dasatinib 70 mg bid PO |

| ER, PR |

Protein expression >10% |

Tamoxifen 20 mg qd PO (or letrozole 2.5 mg qd PO if contra-indication) |

| AR | Protein expression >10% | Abiraterone 1000 mg qd PO |

Abbreviations: AR=androgen receptor; bid=twice a day; ER=oestrogen receptor; IHC=immunohistochemistry; IV=intravenously; LOH=loss of heterozygosity; mTOR=mammalian Target Of Rapamycin; PO=orally; PR=progesterone receptor; qd=daily; q3w=every 3 weeks.

Druggable focal amplification was defined as gene copy number ⩾6 for diploid tumours and ⩾7 for tetraploid tumours and an amplicon size of ⩽1 Mb or ⩽10 Mb if protein overexpression confirmed by IHC.

In case of several alterations, the prioritization of the molecular abnormalities is discussed by the MBB based on the following criteria: (1) In case of expression of both AR and ER/PR in a same patient, the hormone receptor with the highest expression level is taken into account. (2) Any mutation, amplification, or deletion is considered of a higher impact than hormone receptor expression. (3) In case of several mutation/amplification/deletion, the MBB decides based on the latest literature review to select the most ‘relevant' anomaly. In general, abnormalities with clinical validation such as HER-2 overexpression or V600E BRAF mutation prevail. Well characterised mutations such as PI3KCA mutations (E542K, E545K/Q, H1047L/R) are also on the top of the list. (4) KRAS mutations as a resistance biomarker are taken into account only for EGFR amplification or activating mutation (i.e., erlotinib is not given in case of EGFR activation associated with a KRAS mutation).

The control arm was conventional but non standard of care chemotherapy as per oncologist's choice.

End points

The primary end point of the study is PFS defined as death or progression according to RECIST 1.1 (Eisenhauer et al, 2009). End points of the feasibility part of the trial included the determination of the proportion of patients who underwent a biopsy/resection of a metastasis, the rate of complications related to the biopsy, the proportion of patients whose tumour biopsy had a cellularity of ⩾50%, the proportion of patients for whom the mutation and the gene copy number analyses were successful, the proportion of patients for whom the determination of hormone receptors was successful, the proportion of patients for whom a complete tumour profile could be obtained, the proportion of patients in whom a molecular abnormality for which an MTA available within the trial was identified, and the median timeframe between the tumour biopsy and the MBB.

Statistics

The objective of the study was to detect a modification of the PFS between the two randomised arms. The expected 6-month PFS in the control arm was 15% (Horstmann et al, 2005). It was hypothesised that the experimental arm would improve PFS by 40% (HR=0.625). A total of 142 events were requested to detect a statistically significant difference with a type I error of 5% and a power of 80% in a bilateral setting. To observe these events, 90 patients have to be included in each arm. Assuming that 5% of patients will not be evaluable for PFS, a total number of 200 patients were required. The sample size for the feasibility step has been chosen to reach some accuracy in the estimate of the prevalence of molecular abnormalities eligible for randomization: Expecting a point estimate of 20%, 100 patients were necessary to obtain a 95% one-sided confidence interval with lower boundary of 13%.

Results

General results

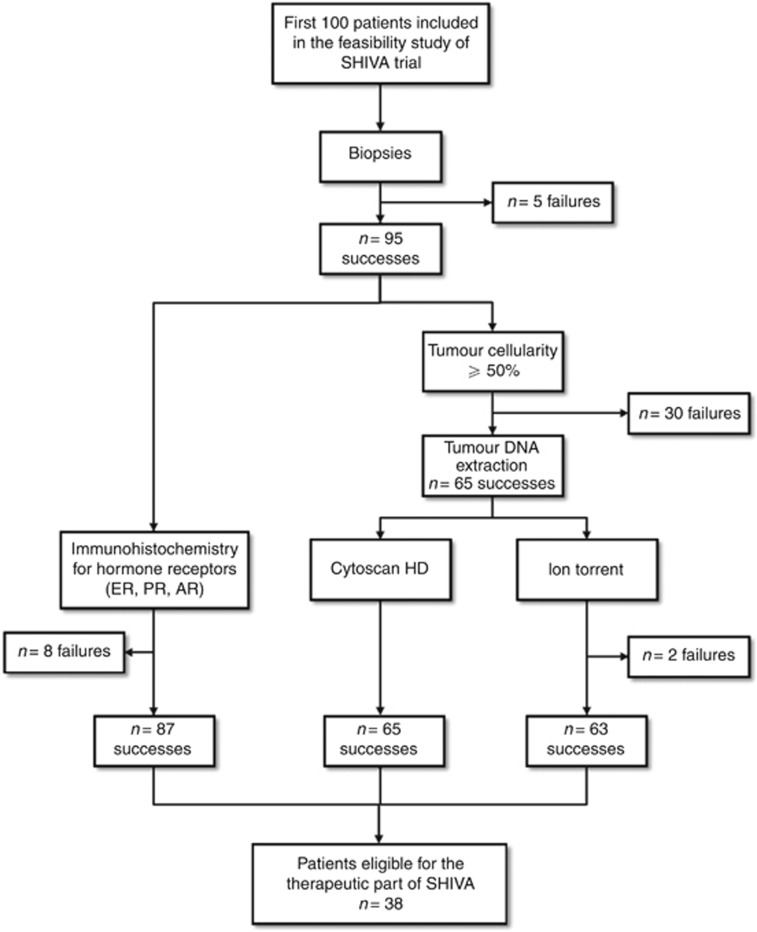

The first hundred screened patients were included between October 2012 and February 2013 in seven French cancer centres. Patient characteristics are presented in Table 2. All but five patients (95%) had a tumour sample taken (Figure 2). The reasons for tumour sample failure included a technical inaccessibility of the metastasis during a CT-guided biopsy (three patients) and the absence of visible tumour (two patients).

Table 2. Patient characteristics (n=100).

| Characteristic | No. of patients | % | Median | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age |

|

|

63 |

25–82 |

|

Gender | ||||

| Female | 66 | 66 | ||

| Male |

34 |

34 |

|

|

|

Tumour location and histology | ||||

| Breast adenocarcinoma |

28 |

28 |

|

|

|

Lung cancer | ||||

| Non-small cell carcinoma | 12 | 12 | ||

| Neuroendocrine tumour | 1 | 1 | ||

| Small cell carcinoma | 1 | 1 | ||

| Mesothelioma |

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

Ovarian cancer | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 7 | 7 | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma |

2 |

2 |

|

|

|

Head and neck cancer | ||||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 5 | 5 | ||

| Adenoid cystic carcinoma | 4 | 4 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma |

1 |

1 |

|

|

| Colorectal adenocarcinoma |

5 |

5 |

|

|

|

Sarcoma | ||||

| Soft tissue sarcoma | 4 | 4 | ||

| Osteosarcoma | 1 | 1 | ||

| Leiomyosarcoma | 1 | 1 | ||

| Uterine leiomyosarcoma | 1 | 1 | ||

| Uterine sarcoma |

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

Cervical cancer | ||||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 3 | 3 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma |

2 |

2 |

|

|

| Urothelial carcinoma |

3 |

3 |

|

|

|

Oesogastric carcinoma | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 3 | 3 | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma |

1 |

1 |

|

|

| Anal squamous cell carcinoma |

2 |

2 |

|

|

| Adenocarcinoma of unknown primary |

2 |

2 |

|

|

|

Endometrial carcinoma | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 1 | 1 | ||

| Small cell carcinoma | 1 | 1 | ||

| Undifferentiated carcinoma |

1 |

1 |

|

|

| Pancreatic adenocarcinoma |

1 |

1 |

|

|

| Germ cell tumour |

1 |

1 |

|

|

| Penis squamous cell carcinoma |

1 |

1 |

|

|

| Vulva squamous cell carcinoma |

1 |

1 |

|

|

| Merckel cell tumour |

1 |

1 |

|

|

| Desmoid tumour | 1 | 1 | ||

Figure 2.

CONSORT diagram for the 100 patients included in the feasibility part of the SHIVA trial. AR=androgen receptor; ER=oestrogen receptor; PR=progesterone receptor.

Among the 95 patients who had a tumour sample taken, a biopsy was performed in 83 patients (87%) and a resection in 12 patients (13%). Tumour sample was taken under local anaesthesia in 83 patients (87%) and general anaesthesia in 12 patients (13%). Lung, liver, skin, and lymph nodes represented 79% of all tumour sampling sites (Table 3). The only reported complication was an uncomplicated pneumothorax following a CT-guided lung biopsy (1%).

Table 3. Sites of tumour samples (n=95).

| Sites | No. of patients | % |

|---|---|---|

| Lung |

21 |

22 |

| Liver |

19 |

20 |

| Skin |

18 |

19 |

| Lymph node |

17 |

18 |

| Peritoneum |

4 |

4 |

| Head and neck |

3 |

3 |

| Breast |

2 |

2 |

| Oesophagus |

2 |

2 |

| Vagina |

2 |

2 |

| Urothelium |

1 |

1 |

| Adrenal gland |

1 |

1 |

| Anus |

1 |

1 |

| Pancreas |

1 |

1 |

| Cervix |

1 |

1 |

| Testis |

1 |

1 |

| Muscle | 1 | 1 |

Molecular profile

Diagnostic confirmation and IHC analyses for hormone receptors were performed in 87 out of the 95 patients (92%) on the paraffin-embedded sample (Figure 2). These analyses were not performed in eight patients (8%) because of the absence of tumour cells in the samples. Tumour cellularity on the frozen sample was <50% in 30 out of the 95 patients (32%). Genomic analyses were therefore performed for 65 patients (68%). Gene copy number analyses met quality criteria in all the 65 patients, while a technical problem occurred in two patients for mutations analyses. Overall, 58 out of the 95 patients (61%) had a complete molecular profile. Median timeframe from tumour biopsy/resection to MBB was 26 days (range: 14–42).

Incidence and types of druggable molecular abnormalities

Among the 95 patients included, 38 patients (40% with a low boundary for the confidence interval of 32%) had a molecular abnormality for which an MTA was available in the frame of the trial (Table 4). The molecular abnormality related to the hormone receptor pathway, the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, and the MAPK pathway in 23 (61%), 13 (34%), and 2 (5%) patients, respectively.

Table 4. Molecular abnormalities matching a molecularly targeted agent available in the frame of the SHIVA trial.

| |

|

Molecular pathway |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumour type and histology | N (%) (n=95) | PI3K/AKT/mTOR | Hormonal | MAPK |

| Breast adenocarcinoma | 9 (9%) | AR+ | ||

| 2 (2%) | PI3KCA mutation (Glu545Lys) | |||

| 2 (2%) | PI3KCA mutation (His1047Arg) | |||

| |

1 (1%) |

PTEN deletion |

|

|

| Ovarian adenocarcinoma | 3 (3%) | ER±PR+ | ||

| 1 (1%) | AR+ | |||

| |

1 (1%) |

Gains of AKT2, mTOR, RPTOR |

|

|

| Lung adenocarcinoma | 1 (1%) | HER2 amplification | ||

| 1 (1%) | STK11 loss+mutation (Asp194Leu) | |||

| 1 (1%) | PTEN loss | |||

| |

1 (1%) |

AKT1 amplification |

|

|

| Cervix squamous cell carcinoma | 1 (1%) | PI3KCA mutation (Glu545Lys) + | ||

| STK11 loss+mutation (Phe345Leu) | ||||

| |

1 (1%) |

|

ER+ |

|

| Cervix adenocarcinoma |

2 (2%) |

|

ER+ |

|

| HNSCC | 1 (1%) | PI3KCA mutation (Glu545Lys) | ||

| |

1 (1%) |

Gains of AKT1, AKT2, PI3KCB, RICTOR

Loss of STK11 |

|

|

| Urothelial carcinoma |

1 (1%) |

|

ER+ |

|

| Anal squamous cell carcinoma |

1 (1%) |

PI3KCA mutation (Glu545Lys) |

|

|

| Mesothelioma |

1 (1%) |

|

AR+ |

|

| Lung small cell carcinoma |

1 (1%) |

|

AR+ |

|

| Soft tissue sarcoma |

1 (1%) |

|

AR+ |

|

| Uterine leiomyosarcoma |

1 (1%) |

|

PR+ |

|

| Uterine sarcoma |

1 (1%) |

|

|

PDGFRA activation |

| Endometrial adenocarcinoma |

1 (1%) |

|

AR+ |

|

| Merckel cell tumour |

1 (1%) |

|

ER+ |

|

| Total | 38 (40%) | 13 (13%) | 23 (24%) | 2 (2%) |

Abbreviations: AR=androgen receptor; ER=oestrogen receptor; HNSCC=head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; mTOR=mammalian Target Of Rapamycin; PR=progesterone receptor; SCLC=small cell lung cancer.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that the establishment of a comprehensive tumour molecular profile on a metastasis is safe, feasible, and compatible with clinical practice in cancer patients. Molecular pathways involved in tumour survival and progression are often enacted by genetic alterations, and cancer progression is thought to be a multistep acquisition of genetic and epigenetic events in tumour cells (Gerlinger et al, 2012). Despite this assumption, differences in specific molecular alterations between primary tumours and metastases were not consistently reported (Vignot et al, 2012). While discordances were frequently reported in breast cancer (Dupont Jensen et al, 2011; Amir et al, 2012), they were barely reported in colorectal and lung cancers (Vakiani et al, 2012; Vignot et al, 2013). Concordance may be influenced by tumour type, type of molecular alteration and prior therapy, especially MTAs (Sequist et al, 2011). In a study involving a similar patient population, a discordance rate of 12% was reported (Tran et al, 2013). A tumour sample from a metastasis was therefore considered as mandatory for the establishment of the tumour molecular profile in our study. Complications' rate observed in our study was low and stand in the lower range of what has been previously reported in studies involving a similar patient population (El-Osta et al, 2011; Gomez-Roca et al, 2012; Tran et al, 2013).

Most of the patients included in our study had a successful IHC analysis. In contrast, the genomic analyses could not be performed in 32% of patients because of a tumour cellularity of <50%. In the MOSCATO01 study in which similar high-throughput technologies were used, the success rates were 88% for mutations analyses and 84% for gene copy number alteration analyses, respectively (Hollebecque et al, 2013). These higher success rates are most probably due to a lower tumour cell percentage thresholds required, namely 10% and 30% for mutation and gene copy number analyses, respectively. Higher rates were also reported in studies not using high-throughput technologies (Von Hoff et al, 2010; Kim et al, 2011; Tsimberidou et al, 2012), or allowing repeated biopsies (Tran et al, 2013). In the SAFIR01 study in which a 50% threshold for tumour cellularity was used for gene copy number analyses, the success rate was in the same range than that of our study (71%) (Andre et al, 2013). The tumour molecular profile was performed within 4 weeks in our study, which is in the range of what has been reported in studies using high-throughput technologies (Roychowdhury et al, 2011; Rodón et al, 2012; Hollebecque et al, 2013; Tran et al, 2013).

Druggable molecular abnormalities were defined in our study as molecular abnormalities that were thought to be relevant biomarkers of efficacy for 11 MTAs already on the market in France. Biomarkers were considered as relevant if they were validated in the clinic, such as HER2 amplification, or if the MBB considered clinical and/or preclinical data to be robust enough. Molecular abnormalities for which no MTA was available in the frame of the SHIVA trial but that were relevant to guide the patient in a clinical trial were mentioned in the molecular report but not considered druggable for the trial. If excluding molecular abnormalities related to the hormone receptor pathway, then only 16% of the 95 patients who underwent a biopsy had a druggable molecular abnormality. When considering only the 65 patients for whom genomic analyses were performed, 24% of patients harboured a druggable molecular abnormality, as compared with ranges of 32–40% patients reported in other studies with similar genomic analyses (MacConaill et al, 2009; Tsimberidou et al, 2012; Hollebecque et al, 2013; Tran et al, 2013). The lower rate of patients harbouring a druggable molecular abnormality in our study might be explained by (1) the use of different thresholds for tumour cellularity to allow the analyses, (2) the criteria used to validate an amplification or a deletion might be more stringent in our study, and (3) the definition of a druggable molecular abnormality does only encompass molecular abnormalities that are druggable with selected MTAs.

While our study demonstrates that the establishment of a comprehensive tumour molecular profile on a metastasis is safe, feasible, and compatible with clinical practice in refractory cancer patients, several issues remain to be addressed. First, some of the biomarkers considered in the algorithm were selected on preclinical studies but have not been validated in the clinic. Some biomarkers of the algorithm have been validated in the clinic in a specific tumour type but might not be validated on other tumour types. While BRAF V600E-mutated melanoma patients are usually sensitive to BRAF inhibitors, it is rarely the case for BRAF V600E-mutated colorectal cancer patients. Moreover, resistance biomarkers with the exception of KRAS mutations were not considered in our algorithm. Second, MTAs are mostly used as single agents in our study, which we know is a limit for prolonged efficacy. Treatment combinations were not allowed even if molecular abnormalities related to different pathways were detected in the same patients. Third, tumour heterogeneity within a metastasis and across metastases has been well described and cannot be addressed with a single tumour sample.

The SHIVA trial is the first histology-independent randomised trial using high-throughput technologies to determine molecularly targeted therapy in patients with refractory cancer. Accrual is ongoing and efficacy results should be available in 2016.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the grant ANR-10-EQPX-03 from the Agence Nationale de le Recherche (Investissements d'avenir) and SiRIC (Site de Recherche Intégré contre le Cancer). High-throughput sequencing has been performed by the NGS platform of the Institut Curie, supported by the grants ANR-10-EQPX-03 and ANR10-INBS-09-08 from the Agence Nationale de le Recherche (investissements d'avenir) and by the Canceropôle Ile-de-France.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website (http://www.nature.com/bjc)

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Material

References

- Amir E, Miller N, Geddie W, Freedman O, Kassam F, Simmons C, Oldfield M, Dranitsaris G, Tomlinson G, Laupacis A, Tannock IF, Clemons M. Prospective study evaluating the impact of tissue confirmation of metastatic disease in patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:587–592. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.5232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andre F, Bachelot T, Campone M, Arnedos M, Dieras V, Lacroix-Triki M, Lazar V, Gentien D, Cohen P, Goncalves A, Lacroix L, Chaffanet M, Dalenc F, Mathieu MC, Bieche I, Olschwang S, Wang Q, Commo F, Jimenez M, Bonnefoi HR.2013Array CGH and DNA sequencing to personalize targeted treatment of metastatic breast cancer (MBC) patients (pts): a prospective multicentric trial (SAFIR01) J Clin Oncol 31(abstr 511). [Google Scholar]

- Arkenau HT, Barriuso J, Olmos D, Ang JE, de Bono J, Judson I, Kaye S. Prospective validation of a prognostic score to improve patient selection for oncology phase I trials. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2692–2696. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.5081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell KL, Burstein HJ, Storniolo AM, Rugo HS, Sledge G, Aktan G, Ellis C, Florance A, Vukelja S, Bischoff J, Baselga J, O'Shaughnessy J. Overall survival benefit with lapatinib in combination with trastuzumab for patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive metastatic breast cancer: final results from the EGF104900 study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2585–2592. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.6725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doroshow JH. Selecting systemic cancer therapy one patient at a time: is there a role for molecular profiling of individual patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4869–4871. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont Jensen J, Laenkholm AV, Knoop A, Ewertz M, Bandaru R, Liu W, Hackl W, Barrett JC, Gardner H. PIK3CA mutations may be discordant between primary and corresponding metastatic disease in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:667–677. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M, Rubinstein L, Shankar L, Dodd L, Kaplan R, Lacombe D, Verweij J. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Osta H, Hong D, Wheler J, Fu S, Naing A, Falchook G, Hicks M, Wen S, Tsimberidou AM, Kurzrock R. Outcomes of research biopsies in phase I clinical trials: the MD Anderson cancer center experience. Oncologist. 2011;16:1292–1298. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlinger M, Rowan AJ, Horswell S, Larkin J, Endesfelder D, Gronroos E, Martinez P, Matthews N, Stewart A, Tarpey P, Varela I, Phillimore B, Begum S, McDonald NQ, Butler A, Jones D, Raine K, Latimer C, Santos CR, Nohadani M, Eklund AC, Spencer-Dene B, Clark G, Pickering L, Stamp G, Gore M, Szallasi Z, Downward J, Futreal PA, Swanton C. Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:883–892. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Roca CA, Lacroix L, Massard C, De Baere T, Deschamps F, Pramod R, Bahleda R, Deutsch E, Bourgier C, Angevin E, Lazar V, Ribrag V, Koscielny S, Chami L, Lassau N, Dromain C, Robert C, Routier E, Armand JP, Soria JC. Sequential research-related biopsies in phase I trials: acceptance, feasibility and safety. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:1301–1306. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollebecque A, Massard C, De Baere T, Auger N, Lacroix L, Koubi-Pick V, Vielh P, Lazar V, Bahleda R, Ngo-camus M, Angevin E, Varga E, Deschamps F, Gazzah A, Mazoyer C, Richon C, Vassal G, Eggermont AM, Andre F, Soria JC.2013Molecular screening for cancer treatment optimization (MOSCATO 01): A prospective molecular triage trial—Interim results J Clin Oncol 31(abstr 2512). [Google Scholar]

- Horstmann E, McCabe MS, Grochow L, Yamamoto S, Rubinstein L, Budd T, Shoemaker D, Emanuel EJ, Grady C. Risks and benefits of phase 1 oncology trials, 1991 through 2002. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:895–904. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa042220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hupé P, Stransky N, Thiery JP, Radvanyi F, Barillot E. Analysis of array CGH data: from signal ratio to gain and loss of DNA regions. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3413–3422. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim ES, Herbst RS, Wistuba II, Lee JJ, Blumenschein GR, Jr, Tsao A, Stewart DJ, Hicks ME, Erasmus J, Jr, Gupta S, Alden CM, Liu S, Tang X, Khuri FR, Tran HT, Johnson BE, Heymach JV, Mao L, Fossella F, Kies MS, Papadimitrakopoulou V, Davis SE, Lippman SM, Hong WK. The BATTLE trial: personalizing therapy for lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2011;1:44–53. doi: 10.1158/2159-8274.CD-10-0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Tourneau C, Kamal M, Trédan O, Delord JP, Campone M, Goncalves A, Isambert N, Conroy T, Gentien D, Vincent-Salomon A, Pouliquen AL, Servant N, Stern MH, Le Corroller AG, Armanet S, Rio Frio T, Paoletti X. Designs and challenges for personalized medicine studies in oncology: focus on the SHIVA trial. Target Oncol. 2012;7:253–265. doi: 10.1007/s11523-012-0237-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacConaill LE, Campbell CD, Kehoe SM, Bass AJ, Hatton C, Niu L, Davis M, Yao K, Hanna M, Mondal C, Luongo L, Emery CM, Baker AC, Philips J, Goff DJ, Fiorentino M, Rubin MA, Polyak K, Chan J, Wang Y, Fletcher JA, Santagata S, Corso G, Roviello F, Shivdasani R, Kieran MW, Ligon KL, Stiles CD, Hahn WC, Meyerson ML, Garraway LA. Profiling critical cancer gene mutations in clinical tumor samples. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7887. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popova T, Manié E, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, aill G, Barillot E, Stern MH. Genome Alteration Print (GAP): a tool to visualize and mine complex cancer genomic profiles obtained by SNP arrays. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R128. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-11-r128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigaill G.2010. Pruned dynamic programming for optimal multiple change-point detection. arXiv 1004.0887.

- Rodón J, Saura C, Dienstmann R, Vivancos A, Ramón y Cajal S, Baselga J, Tabernero J. Molecular prescreening to select patient population in early clinical trials. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9:359–366. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roychowdhury S, Iyer MK, Robinson DR, Lonigro RJ, Wu YM, Cao X, Kalyana-Sundaram S, Sam L, Balbin OA, Quist MJ, Barrette T, Everett J, Siddiqui J, Kunju LP, Navone N, Araujo JC, Troncoso P, Logothetis CJ, Innis JW, Smith DC, Lao CD, Kim SY, Roberts JS, Gruber SB, Pienta KJ, Talpaz M, Chinnaiyan AM. Personalized oncology through integrative high-throughput sequencing: a pilot study. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:111ra121. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sequist LV, Waltman BA, Dias-Santagata D, Digumarthy S, Turke AB, Fidias P, Bergethon K, Shaw AT, Gettinger S, Cosper AK, Akhavanfard S, Heist RS, Temel J, Christensen JG, Wain JC, Lynch TJ, Vernovsky K, Mark EJ, Lanuti M, Iafrate AJ, Mino-Kenudson M, Engelman JA. Genotypic and histological evolution of lung cancers acquiring resistance to EGFR inhibitors. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:75ra26. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran B, Brown AM, Bedard PL, Winquist E, Goss GD, Hotte SJ, Welch SA, Hirte HW, Zhang T, Stein LD, Ferretti V, Watt S, Jiao W, Ng K, Ghai S, Shaw P, Petrocelli T, Hudson TJ, Neel BG, Onetto N, Siu LL, McPherson JD, Kamel-Reid S, Dancey JE. Feasibility of real time next generation sequencing of cancer genes linked to drug response: results from a clinical trial. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:1547–1555. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsimberidou AM, Iskander NG, Hong DS, Wheler JJ, Falchook GS, Fu S, Piha-Paul S, Naing A, Janku F, Luthra R, Ye Y, Wen S, Berry D, Kurzrock R. Personalized medicine in a phase I clinical trials program: The M. D. Anderson Cancer Center Initiative. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:6373–6383. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vakiani E, Janakiraman M, Shen R, Sinha R, Zeng Z, Shia J, Cercek A, Kemeny N, D'Angelica M, Viale A, Heguy A, Paty P, Chan TA, Saltz LB, Weiser M, Solit DB. Comparative genomic analysis of primary versus metastatic colorectal carcinomas. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2956–2962. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignot S, Besse B, André F, Spano JP, Soria JC. Discrepancies between primary tumor and metastasis: a literature review on clinically established biomarkers. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2012;84:301–313. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignot S, Frampton GM, Soria JC, Yelensky R, Commo F, Brambilla C, Palmer G, Moro-Sibilot D, Ross JS, Cronin MT, André F, Stephens PJ, Lazar V, Miller VA, Brambilla E. Next-generation sequencing reveals high concordance of recurrent somatic alterations between primary tumor and metastases from patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2167–2172. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.7737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Hoff DD, Stephenson JJ, Jr, Rosen P, Loesch DM, Borad MJ, Anthony S, Jameson G, Brown S, Cantafio N, Richards DA, Fitch TR, Wasserman E, Fernandez C, Green S, Sutherland W, Bittner M, Alarcon A, Mallery D, Penny R. Pilot study using molecular profiling of patients' tumors to find potential targets and select treatments for their refractory cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4877–4883. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.5983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: Functional annotation of genetic variants from next-generation sequencing data. Nucl Acids Res. 2010;38:e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.