Abstract

Background:

Stratification of patients for treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is suboptimal, with high systemic overtreatment rates.

Methods:

A training set of 95 tumours from women with pure DCIS were immunostained for proteins involved in cell survival, hypoxia, growth factor and hormone signalling. A generalised linear regression with regularisation and variable selection was applied to a multiple covariate Cox survival analysis with recurrence-free survival 10-fold cross-validation and leave-one-out iterative approach were used to build and test the model that was validated using an independent cohort of 58 patients with pure DCIS. The clinical role of a COX-2-targeting agent was then tested in a proof-of-concept neoadjuvant randomised trial in ER-positive DCIS treated with exemestane 25 mg day−1±celecoxib 800 mg day−1.

Results:

The COX-2 expression was an independent prognostic factor for early relapse in the training (HR 37.47 (95% CI: 5.56–252.74) P=0.0001) and independent validation cohort (HR 3.9 (95% CI: 1.8–8.3) P=0.002). There was no significant interaction with other clinicopathological variables. A statistically significant reduction of Ki-67 expression after treatment with exemestane±celecoxib was observed (P<0.02) with greater reduction in the combination arm (P<0.004). Concomitant reduction in COX-2 expression was statistically significant in the exemestane and celecoxib arm (P<0.03) only.

Conclusions:

In patients with DCIS, COX-2 may predict recurrence, aiding clinical decision making. A combination of an aromatase inhibitor and celecoxib has significant biological effect and may be integrated into treatment of COX2-positive DCIS at high risk of recurrence.

Keywords: DCIS, COX-2, aromatase inhibitor, breast cancer, celecoxib, exemestane

Current treatment of patients with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) includes breast surgery, radiotherapy and hormonal therapy (Fisher et al, 1999; Bijker et al, 2006) as they reduce the risk of in situ and invasive recurrence.

Although the presence of comedonecrosis, architectural subtype, nuclear grade, tumour size and involved margins are factors that increase the probability of recurrence, we are currently unable to predict individual patient's risk of recurrence or progression to invasive disease. Thus, there is an urgency for studies with prolonged follow-up focussed on recurrence to identify predictive and prognostic clinical and/or biological markers of tumour recurrence and that are also able to recognise DCIS patients who may benefit from more targeted therapies.

We have therefore investigated the role of molecular markers recognised to modulate tumour progression. Our goal was to find specific profiles predictive of recurrence-free survival using an initial candidate approach on a training set, with confirmation on a validation cohort. COX-2 was identified as a candidate and a proof-of-concept clinical trial then tested exemestane+celecoxib, administered for 12 weeks before surgery. Paired baseline and end-point biopsies were immunohistochemically analysed for Ki-67 and COX-2 expression as a marker of drug activity. The primary end point was a decrease in Ki-67 and COX-2 between diagnosis and surgical excision.

Patients and methods

Patient cohorts

Using the REMARK criteria (McShane et al, 2005), the flow of patients through the study was as follows: 174 patients were retrospectively accrued from the John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK, and from the Royal Brisbane and Women's Hospital, Brisbane, Australia. Of the cases, 116 from Oxford were available for tissue microarray (TMA) construction, of which 95 were available for COX-2 staining because of core dropout. This training set cohort and the TMA was also stained for phospho-mTOR, HGF/HAI-2, HIF-1α, CAIX, PHD1, PHD2, PHD3, pEGFR, HER2, HER3, COX-2, pERα, FOXP3, FOXP1 and Cyclin D1. The 58 cases from the Royal Brisbane and Women's Hospital formed the validation set. The COX-2 staining was performed on whole sections on all 58 cases and a subset of 33 cases was also stained for PHD2 and CAIX. Ethical committee permission for the study was obtained from both Institutions (CO.216 for Oxford, UK, and UQ number 2005000785 for Brisbane, Australia). All patients had pure DCIS treated with surgery (Table 1a). Median age of patients in the training cohort was 56 years (range 33–75 years) and in the validation cohort was 55 years (range 29–80 years). In the training and validation cohort, 10 (10.5%) and 15 (25.9%) cases had close surgical margins (<1 mm). Patients were followed-up for a median period of 126 and 164 months, respectively, in the training and validation cohort. Sixteen patients out of 95 in the training set and 10 patients out of 58 in the validation set have received radiotherapy. During this time, 40 (42.1%) patients developed a recurrence (69.2% ipsilateral) in the training cohort, of which 14 cases were of invasive carcinoma, with 2 cases of metastatic disease without evidence of recurrent DCIS or invasive carcinoma in the breast. In the validation set, 28 (48.3%) patients developed a recurrence (92.9% ipsilateral), of which 11 cases were of an invasive carcinoma and included one case of metastatic disease without evidence of recurrent DCIS or invasive carcinoma in the primary or subsequent excision. Demographic information is provided in Table 1a.

Table 1a. Clinicopathological details of patients.

| Training set | Validation set | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients |

95 |

58 |

| Median follow-up |

126 Months |

164 Months |

| Median age |

56 Years |

55 Years |

| Median time to recurrence |

40 Months |

59 Months |

|

Primary excision | ||

| Breast conserving | 79 (83.2%) | 55 (94.8%) |

| Mastectomy |

16 (16.8%) |

3 (5.2%) |

|

Nodes examined | ||

| Yes | 59 (62.1%) | 5 (8.6%) |

| No | 36 (37.9%) | 53 (91.4%) |

| Node-positive cases |

2 |

0 |

| Margins <1 mm |

10 (10.5%) |

15 (25.9%) |

|

Radiotherapy | ||

| Yes | 16 (16.8%) | 10 (17.2%) |

| No | 77 (81.1%) | 0 |

| Unknown |

2 (2.1%) |

48 (82.8%) |

| Number of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) recurrences |

26 (27.4%) |

17 (29.3%) |

| Number of invasive recurrences | 14 (14.7%) | 11 (19.0%) |

Tissue microarray and immunohistochemistry

Haematoxylin and eosin-stained slides of cases from the training set were reviewed and TMAs with 2 mm diameter cores, with four-fold redundancy, from areas of DCIS were prepared. Whole sections of DCIS were stained from the validation set. Immunohistochemistry was performed using the EnVision HRP kit (Dako, Cambridgeshire, UK) system.

Staining was assessed in the Oxford-derived test set for nuclear protein expression for HIF1-α (hypoxia inducible factor-1α), forkhead box protein 3 (FOXP3), phospho oestrogen receptor-α (pERα), cyclin D1, nucleus and cytoplasm for prolyl hydroxylase 1 (PHD1), PHD2, PHD3, FOXP1, membrane for carbonic anhydrase-IX (CAIX), phospho-epidermal growth factor receptor (pEGFR), HER2 and HER3, cytoplasm for phospho-mTOR, COX-2, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and hepatocyte growth factor activator inhibitor-type 2 (HAI-2). Separate pathologists, blinded to patient outcome and to the origin of the samples, used a semiquantitative method to score the TMAs and whole sections from the validation set.

As previously used (Tan et al, 2009), intensity was semiquantitively assessed. The cutoff for FOXP3, FOXP1, HER2 NS HER3 was as previously reported (Generali et al, 2009). A histoscore was generated by multiplying intensity (0–3) by percentage (0–4) to give a final score between 0 and 12. For categorisation of the validation cohort, using cutoffs from previous breast cancer studies, tumours that showed strong membranous staining in >10% of cells were considered positive for CAIX (Tan et al, 2009), tumours with intermediate to strong cytoplasmic intensity in any tumour cell were considered positive for PHD1 expression (Fox et al, 2011) and a histoscore of 0–3/12 defined a group with low COX-2 expression, whereas a score of 4–12/12 defined the group with high COX-2 expression (Figure 1). This was either identical to or comparable to cutoffs used for COX-2 by others evaluating expression in breast tumours ( Half et al, 2002; Boland et al, 2004; Kerlikowske et al, 2010). The cutoffs used in histoscore calculation for COX-2 were 0 (0), 1 (<25%), 2b(25⩽50), 3 (50⩽75) and 4 (⩾75). The control used was colon and a known positive for colorectal adenocarcinoma. For pERα, the Allred score was used as a continuous variable (Leake et al, 2000; Mohsin et al, 2004).

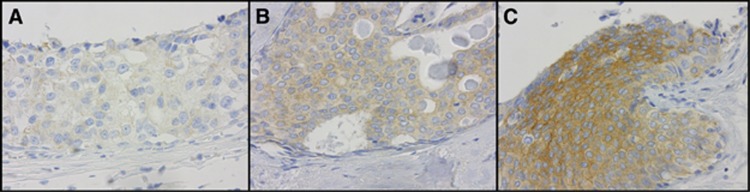

Figure 1.

The COX-2 immunohistochemical staining of DCIS showing 1+ (A), 2+ (B) and 3+ (C) staining intensity.

The approach to missing cases was to exclude cases where the value of the covariate under study was missing in the univariate analysis and to exclude cases when one or more covariates were missing in the multiple covariate analysis.

Immunohistochemical evaluation of routine markers performed on whole DCIS sections obtained at diagnosis and definitive surgery in the clinical trial was performed as described previously (Bottini et al, 2000). The COX-2 immunohistochemistry and scoring was identical to that used previously in the training TMAs and validation set.

Clinical trial

To assess the effect of a COX-2 inhibitor on tumour response and the relationship to COX-2 expression, we performed a single-centre, randomised, phase II neoadjuvant trial in which postmenopausal patients with diagnosis of pure ER-positive (non-comedo) DCIS were randomly assigned 1 : 1 to one of the two following treatment arms: 25 mg daily exemestane alone (EXE arm) orally or 25 mg daily exemestane and 800 mg daily celecoxib (EXE–COXIB arm) orally given continuously for 12 weeks until definitive surgery after initial core biopsy diagnosis. The diagnosis was performed using Mammotone-based vacuum-assisted 16-G multi-site biopsy procedure (Ethicon Endosurgery, Cincinnati, OH, USA). Titanium clips were centrally located in biopsy site. Between November 2003 and November 2004, 32 eligible patients with informed consent were enrolled from U.O.M. Patologia Mammaria-Breast Unit of Az. Istituti Ospitalieri di Cremona, Italy (protocol no. Ex01/4111/04). The trial was prematurely stopped because of the COX-2 inhibitor-related alerts about their association with cardiovascular adverse events. Tumour size, response and lumpectomy as surgical procedures followed by radiation with 50 Gy in 25 fractions over 5 weeks were assessed as previously described (Bottini et al, 2006; see Supplementary Figure S1). All patients received exemestane as adjuvant therapy for 5 years.

Statistical analysis

A generalised linear regression method with regularisation and variable selection was applied within a multiple covariate Cox survival analysis with the aim of finding expression profiles correlated with recurrence-free survival. An L-1 and L-2 penalised maximum-likelihood method was used to select the significant parameters in the model; 10-fold cross-validation and leave-one-out iterative approach were used to build and test the model respectively as described by Generali et al (2009) and Buffa et al (2011). Treatment, age and tumour grade were included in the analysis. Where both percentage cells (PCs) and intensity (INT) were scored they were both included in the analysis; when both of them resulted significant the gain from using a combined score was tested including their product as a further term in the model. The significance of this term was tested using the same method as previously described. The criteria for marker inclusion and exclusion have been described previously (Generali et al, 2009); the markers introduced in the model are described in Table 1a where median, mean and 95% confidence interval (CI) are provided. The analysis was done using SPSS version 15 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA); the cross-validation and leave-one-out analyses were implemented in R 2.5.1 (http://cran.r-project.org) and the R package elastic-net was used to perform the penalised regression (Zou and Hastie, 2005). A categorical method of analysis was performed on the validation set.

Regarding the clinical trial, results were expressed as geometric means and CIs, although the analysis was conducted on the log-transformed data. Primary end point was an absolute reduction in DCIS proliferation as measured by Ki-67 labelling index and COX-2 expression. To calculate required sample size for adequate power, we anticipated at least a 10% greater reduction in proliferation index (Ki-67) between the EXE–COXIB and EXE arms in COX2-expressing cases (anticipated incidence of COX-2 expression being 60% (Bundred et al, 2010) of all cases). Preliminary evaluation of Ki-67 in DCIS showed a mean of 12.3% and s.d. of 1.3%. The study therefore required 28 patients in each arm with the assumption that 100% of patients enrolled would be evaluated. Providing for an attrition rate of 10%, we aimed to recruit 32 patients into each cohort. Using the anticipated number of patients outlined above, we would require at least 66% of COX-2-positive patients to show a decrease in the EXE–COXIB arm and <10% of COX-2-positive cases in the EXE arm to show any significant reduction. As celecoxib is a potent COX-2 inhibitor, we anticipated that the reductions seen in each arm were conservatively realistic. All tests were performed two-sided and P-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed with STATISTICA software system (version 6, Tulsa, OK, USA: www.statsoft.com).

Results

Factors associated with DCIS early relapse

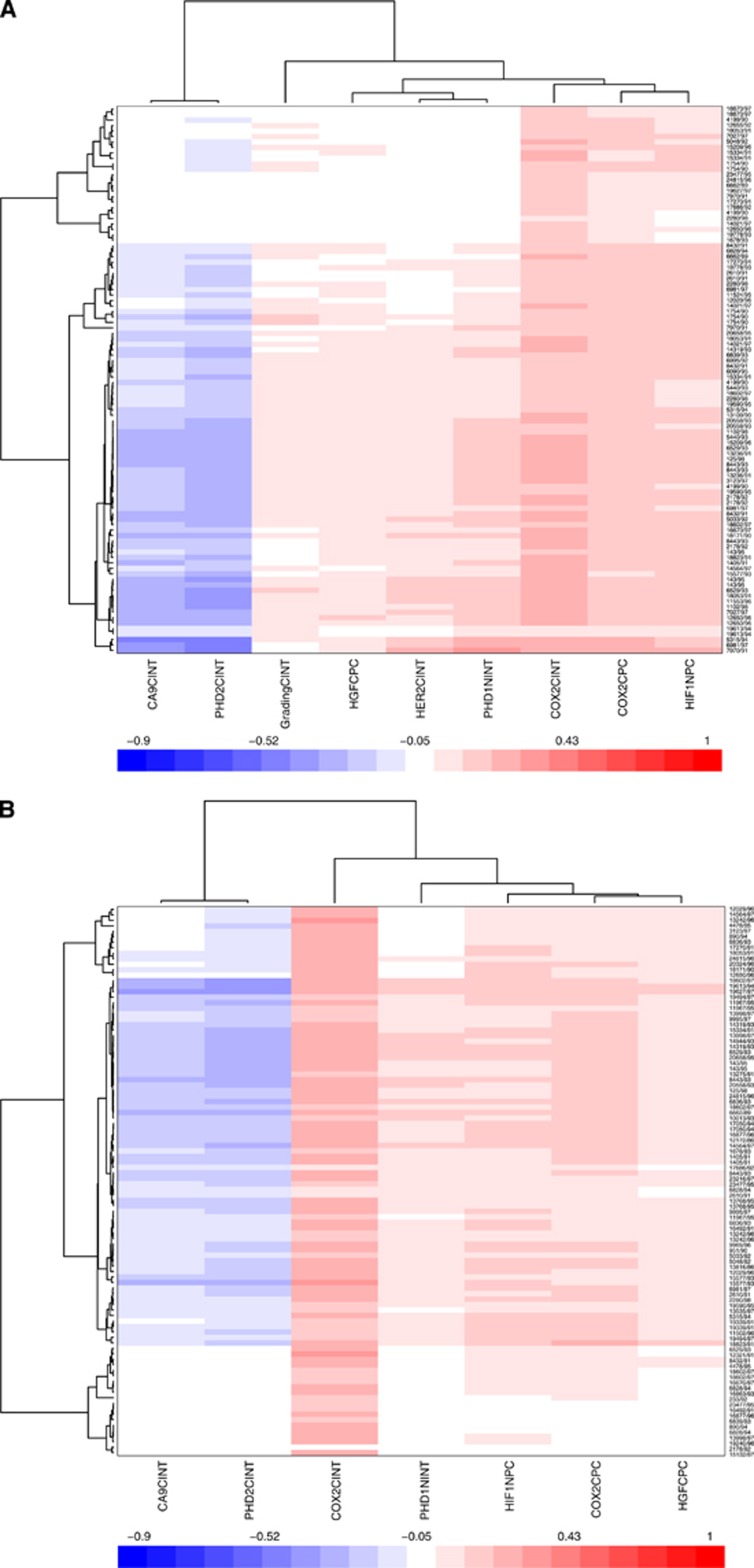

In the 10-fold cross-validation and leave-one-out iterative analysis, COX-2 cytoplasmic expression was the strongest independent prognostic factor for early relapse of DCIS. It was present in the relapse model in all leave-one-out iterations (Figure 2A and B). As both PC and INT scores were significant for this marker, the combined score (the product histoscore of % cells and intensity) was introduced in the model and resulted as a stronger prognostic factor than the two scores considered separately (Figure 2C). In addition, HIF-1α cytoplasm PC, PHD1 nuclear INT and HGF cytoplasmic PC were significant in the model (Figure 2A) and high scores for these markers were associated with early relapse in 80%, 82% and 97% of the iterations, respectively.

Figure 2.

(A) Ten-fold cross-validation and leave-one-out iterative analysis. (A) Multiple covariate Cox analysis including all markers that passed the threshold (both PC and INT scores). The methods and results are discussed in the text. (B) Multiple covariate Cox analysis including all markers and clinical variables. (C) Multiple covariate Cox analysis including interaction terms for markers where both PC and INT were significant.

Factors associated with DCIS disease-free survival

The CAIX membrane INT and PHD2 cytoplasmic INT were associated with good prognosis in 81% and 89% of iterations, respectively (Figure 2A and B ). This unexpected result for CAIX and PHD2 was confirmed in both univariate analysis and multiple covariate Cox regression, demonstrating that it is not an artefact due to correlations of the variables in the Cox model. Furthermore, we have tested it as a possible artefact because of different diagnosis methods as some patients were or were not diagnosed by mammographic screening. However, there was no significant correlation with method of diagnosis and CAIX or PHD2 expression. When the two groups were separated and the survival analysis was repeated in the two groups independently, the same results were observed in the two groups and they were similar to the results observed for the whole cohort, although the significance was lower because of a smaller number in each group. We conclude that the method of detection modality does not affect the results observed for CAIX and PHD2. Interaction of any of these factors (markers or early relapse or long disease-free survival) with the other clinical variables considered in this study was not significant when interaction terms were included in the linear regression (data not shown). Recently, CAIX expression in cell lines and xenografts was shown to be associated with an increase in necrosis, and this in the context of DCIS may relate to slowing growth (McIntyre et al, 2012).

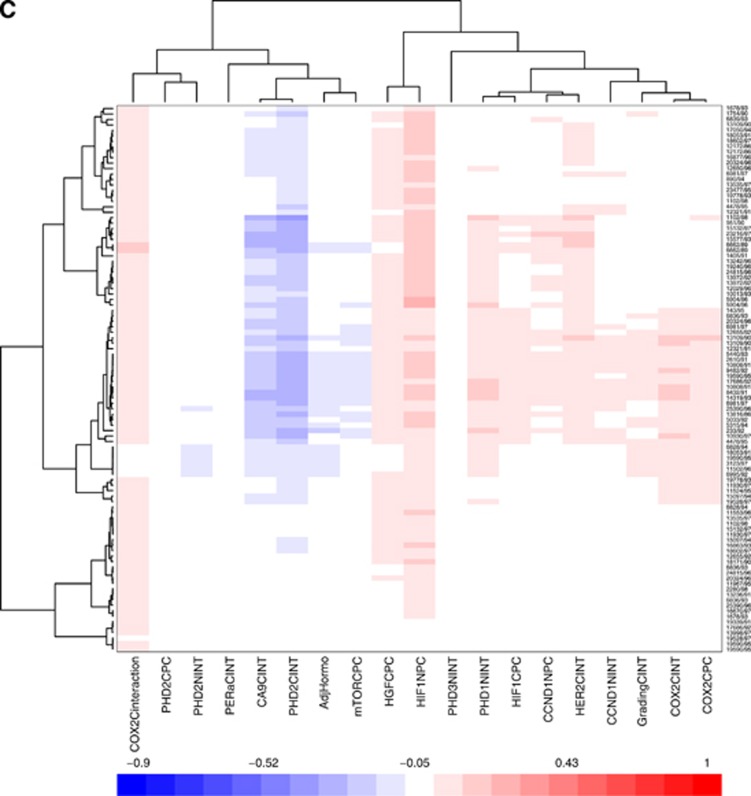

COX-2 cytoplasmic expression associated with relapse in an independent validation cohort

In the independent 58-case validation set, high COX-2 expression was confirmed as a prognostic factor for early relapse of either DCIS or progression to invasive carcinoma (HR 3.9 (95% CI: 1.8–8.36) P=0.002; Figure 3). The COX-2 expression showed no correlation with patient age, size and grade of DCIS or margins of the primary excision (Table 1b). The prognostic significance of CAIX and PHD2 expression was not confirmed in the validation set. High expression of CAIX in DCIS correlated with increased size of DCIS (mean 33.1 vs 15.5 mm, P=0.01), but there was no other association between CAIX, PHD2 expression and clinicopathological factors.

Figure 3.

Recurrence-free survival of patients with DCIS stratified by COX-2 in the validation set.

Table 1b. Stratification of validation set by COX-2 immunohistochemical expression.

| COX-2 negative | COX-2 positive | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients |

30 |

28 |

|

| Median follow-up |

183 Months |

102 Months |

|

| Median age |

51 Years |

59 Years |

NS 0.4a |

| Median time to recurrence |

61 Months |

57 Months |

NS 0.9a |

|

Grade | |||

| Low | 2 (6.7%) | 5 (17.9%) | NSb |

| Intermediate | 7 (23.3%) | 10 (35.7%) | |

| High |

21 (70.0%) |

13 (46.4%) |

|

| Margins <1 mm |

6 (20.0%) |

9 (32.1%) |

NS 0.3b |

| Number of recurrences |

4 (13.3%) |

13 (46.4%) |

0.008b |

| Number of invasive recurrences | 4 (13.3%) | 7 (25.0%) | NS 0.3b |

Abbreviation: NS=not significant.

Unpaired t-test.

Fisher's exact test.

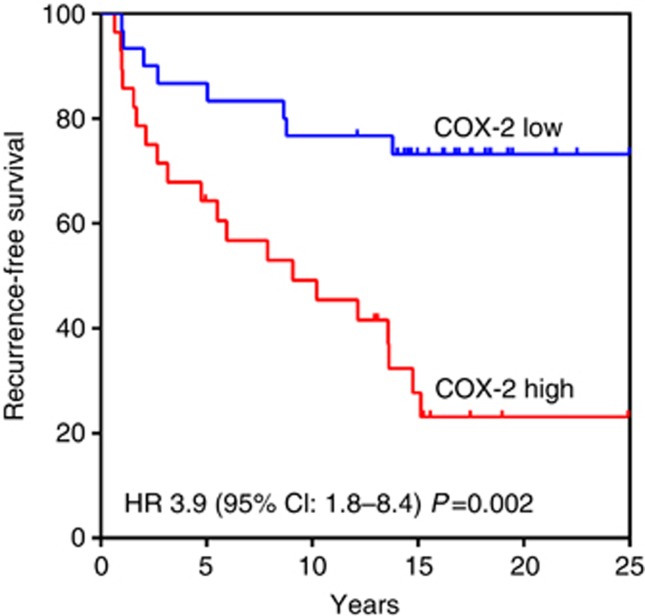

Proof-of-concept clinical trial: treatment activity

A total of 32 patients from a single institution were enrolled in the clinical trial: 14 in the EXE–COXIB arm and 18 in the EXE arm (Supplementary Figure S1). The median DCIS size before starting treatment was 19 mm (range, 12–26 mm) and 100%, 19% and 16%, of DCIS were respectively ER, PR, HER2 positive at diagnosis (basal characteristics are described in Supplementary Table S1). Clinical complete responses (CCRs) were observed in 6 patients in the EXE–COXIB arm and in 5 patients in the EXE arm. A partial response (PR) was observed in 8 patients in both arms and stable disease (SD) was confined to the EXE arm only (n=5). Of the enrolled patients, 100% completed the study and received definitive surgery after 12 weeks of treatment.

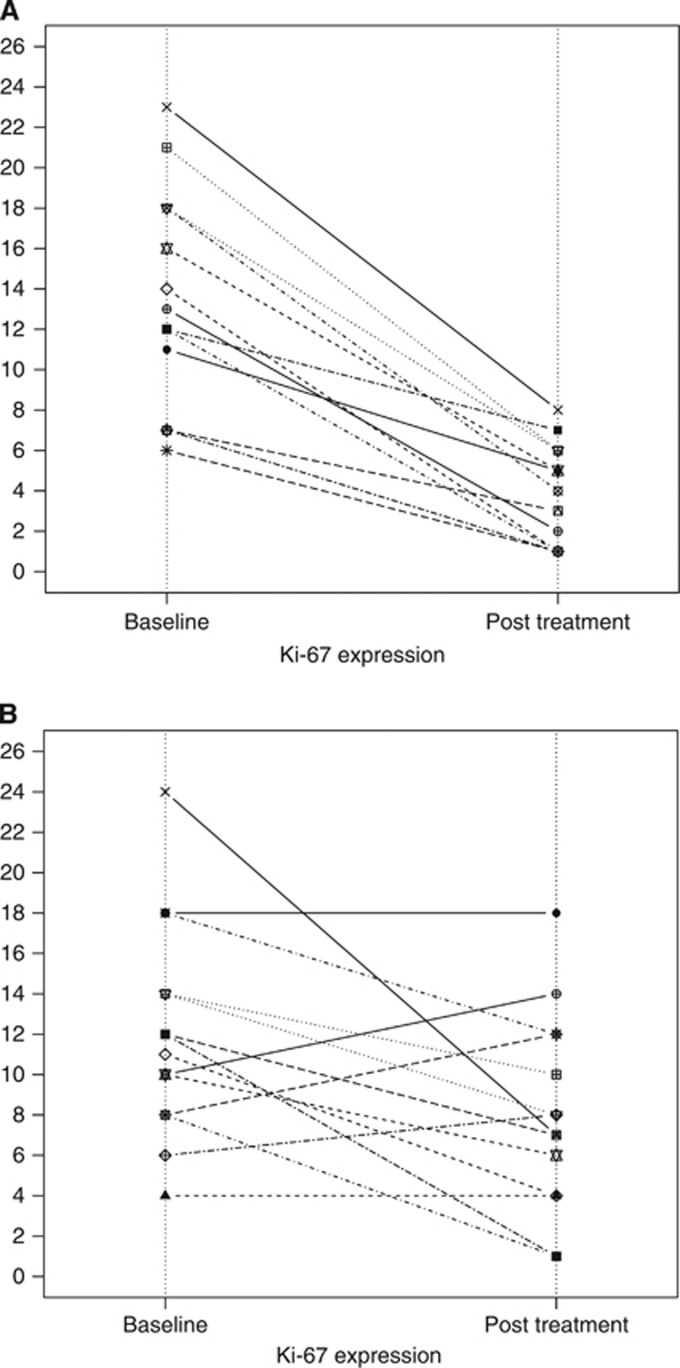

A total of 27 patients (13 in the EXE–COXIB arm and 14 in the EXE arm) had Ki-67 in their DCIS assessed before and after chemotherapy. Ki-67 was not assessable at definitive surgery in 5 DCIS (1 in the EXE–COXIB arm and 4 in the EXE arm) because of lack of tumour material. The median Ki-67 mitotic index fell from 12.5% (range, 6–23%) at initial biopsy to 4% (range, 1–8%) at definitive surgery in the EXE-COXIB arm and from 12% (range, 4–24%) to 7.5% (range, 1–18%) in the EXE arm. Changes in Ki-67 for individual patients according to treatment received are shown in Figure 4. In the EXE–COXIB arm, all patients showed a reduction of Ki-67 after treatment (Figure 4A). In the EXE arm, 3 (21.4%) patients showed a numerical increase in Ki-67 (Figure 4B). Geometric mean changes in Ki-67 are shown for the two treatment arms in Table 2. The two arms were comparable in terms of basal proliferation (P=0.43), whereas EXE–COXIB arm had a significantly lower post-treatment Ki-67 than the EXE arm (P<0.02). The reduction in Ki-67 in both EXE–COXIB and EXE arms was significant for both treatments (P<0.002 and P<0.02, respectively), but there was highly significant difference in the change of Ki-67 between two arms, in favour of the EXE–COXIB arm (P<0.004).

Figure 4.

Changes in Ki-67 expression for patients at baseline and post-treatment histology according to treatment received. The large majority of patients randomised receiving (A) exemestane plus celecoxib (EXE-COXIB arm) and (B) exemestane alone (EXE arm) showed a suppression of Ki-67.

Table 2. Changes in the percentage of cells staining positively for Ki-67 after treatment with exemestane plus celecoxib (EXE–COXIB arm) or exemestane alone (EXE arm).

| EXE–COXIB arm (n=13) | EXE arm (n=14) | P-value of differences between arms | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (%) |

12.65 (10.45–16.93) |

10.98 (9.01–15.13) |

0.43 |

| Post treatment (%) |

2.94 (2.33–5.36) |

6.14 (5.19–10.81) |

<0.02 |

| Relative change: baseline/post treatmenta |

4.31 (2.98–7.61) |

1.79 (0.85–4.63) |

<0.004 |

| Change from baseline P-value | <0.002 | <0.02 |

Abbreviations: COXIB=celecoxib; EXE=exemestane.

Values are given as the geometric means (95% confidence interval).

The Ki-67 expression at post-therapy residual histology was significantly lower in both EXE–COXIB arm (P<0.002) and the EXE arm (P<0.02). The reduction in the combination arm was significantly greater than in single agent (P<0.004).

Relative size of baseline to post-treatment percentages.

A total of 16 patients (7 in the EXE–COXIB arm and 9 in the EXE arm) had COX-2 staining detected in their DCIS assessed before therapy. The two groups of patients (EXE–COXIB vs EXE arm) were comparable in terms of basal COX-2 expression. There was a significant reduction in COX-2 expression in the EXE–COXIB arm (P<0.03) at definitive surgery compared with the initial biopsy, but no significant difference was observed between biopsies in the EXE arm. Expression for individual patients according to treatment received is shown in Supplementary Figure S2A and B. A CCR after treatment was significantly associated with reduction of COX-2 histoscore (CCR in 6 out of 9 cases with reduction of COX-2; P for trend =0.011; Supplementary Figure S2C).

No relapses of DCIS or invasive breast cancer were detected, with a median follow-up of 8 years (range 8.6–7.6 years), in patients enrolled in the trial at the time of writing.

Discussion

Studies show that local control with lumpectomy have an average ipsilateral breast recurrence rates of 43% (Leonard and Swain, 2004), almost half of which is consistently in the form of invasive cancer (Mokbel and Cutuli, 2006; Wapnir et al, 2011). Although further treatment by either whole-breast radiotherapy, completion mastectomy or tamoxifen reduces the risk of local DCIS recurrence or of invasive carcinoma (Fisher et al, 1999; Bijker et al, 2006), blanket treatment of this heterogeneous disease with these more aggressive therapies is not an effective use of current resources and carries significant morbidity (Kane et al, 2010). To date, both randomised trials and observational studies have either not tested predictive markers, have been underpowered or have not controlled for adverse prognostic features and therefore not identified populations in which treatment effect may be most beneficial. The absolute risk reduction in most of these studies is often low that provides little justification for incorporation into current treatment practises (Kane et al, 2010).

The meta-analysis conducted by the EBCTCG showed that radiotherapy reduced the absolute 10-year risk of any ipsilateral breast event by 15.2% independently of the clinical/surgical/therapeutical characteristics, but without any significant impact on breast cancer mortality (Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative et al, 2010). Overall, the real benefit of radiotherapy on DCIS treatment is questionable with respect to its related cost benefit. Under this consideration, our study identifies a possible subgroup characterised by a particular phenotype with a high risk of relapse who could have benefitted more from radiotherapy compared with the low-risk group that do not express determined biological variable. A randomised trial based on the use of radiotherapy in high-risk DCIS (identified by biological variables such as COX-2) is warranted to elucidate a medical need.

Thus, there is a compelling and urgent need for increased understanding of relapse and the progression from DCIS to invasive cancer to avoid the current overtreatment that is established in current practice.

The purpose of this study was to identify a molecular profile able to predict tumour recurrence either as DCIS or invasive breast cancer. To achieve this, a robust statistical analysis approach was used that accounts for multiple covariates, and validates and tests the generality of the model in a recursive manner. From this analysis we identified COX-2 as the strongest prognostic factor for early relapse of DCIS and subsequently confirmed this using an independent cohort. The findings were validated within the separate cohorts using different statistical methodologies, further improving the robustness of the marker.

The overexpression of COX-2 has been demonstrated in both DCIS and invasive breast cancer (Spizzo et al, 2003; Boland et al, 2004), and its expression is associated with a shorter disease-free survival of invasive breast carcinomas (Ristimaki et al, 2002). Kerlikowske et al (2010) evaluated COX-2 expression in 279 cases of DCIS but found no direct association between COX-2 expression and recurrence. The scoring system used (Allred) is different to ours and a portion of their positive samples would be scored as low in our study. Both our training and validation cohorts also have significantly longer follow-up (median 126 and 164 months, respectively) and capture a considerable proportion of later recurrences (35.7%) that would not have been detected with the 8-year cutoff in their study. Kerlikowske et al (2010) did however show that a p16+COX-2+Ki67+DCIS phenotype was prognostic for recurrence and suggests that the biological correlation between COX-2 levels and proliferation may be significant as we have seen within our clinical study.

Biologically, Chang et al (2004) have shown that one of the normal functions of COX-2 is in the regulation of angiogenesis in normal mammary tissue. In tumours, the mechanisms underlying COX-2 are unknown but appears to be associated with increased epithelial proliferation, a low apoptotic rate, metastasis, immune suppression and evasion and tumour angiogenesis, as demonstrated by expression in tumour-associated blood vessels and correlating with tumour microvessels density (measured by CD31 expression; Davies et al, 2003). The COX-2 expression has also been found to correlate with aromatase expression within human breast cancer tissue through increased prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) levels that stimulate aromatase transcription (Barnes et al, 2007). In view of these data, COX-2 inhibitors have been used in combination therapy with hormonal agents, such as aromatase inhibitors, to decrease tumour recurrence.

The use of NSAIDs and potentially COX-2 inhibitors in breast cancer has clinical attraction considering their availability, inexpensiveness and generally good tolerance at lower doses with long-term use (Kearney et al, 2006). A meta-analysis of 38 studies showed a risk reduction of breast cancer (RR 0.88) with NSAID use (Takkouche et al, 2008). More specifically, efficacy of specific targeting of COX-2 in more advanced disease has been suggested by a randomised, phase II study in postmenopausal women (n=111) with advanced breast cancer treated where exemestane and celecoxib resulted in a longer time to breast cancer recurrence compared with exemestane alone, and additional side effects were not observed (Dirix et al, 2008). This, however, was not confirmed by another independent study in the neoadjuvant setting that was unable to demonstrate any increase in response rates to the combination (Chow et al, 2008). In the context of DCIS, Bundred et al (2010) were also unable to show an effect of a difference between exemestane±celecoxib on apoptosis or proliferation in a study of 40 randomised patients. However, treatment was for only 14 days, in contrast to our study that was for 12 weeks, and hence it is likely that in the prior study there was insufficient time to see the changes brought about by longer-term therapy. Nevertheless, our study has shown that exemestane alone and combined with celecoxib induced a profound reduction in tumour cell proliferation that was more marked in the presence of the COX-2 inhibitor. The concomitant administration of celecoxib to the aromatase inhibitor also reduced the COX-2 expression after treatment, suggesting that the presence of celecoxib not only ‘hit the target' but that it may be responsible for the determined clinical and biological effect, and may also play a further role as a potential biomarker for treatment response. As COX-2 also regulates aromatase transcription, the longer 12-week regimen might be responsible for the observed biological effect. Although a clinical benefit was not necessarily seen in our study, this was also not a primary end point and our clinical cohort showed considerably better baseline outcome than reported in the literature and would benefit from validation in a larger randomised control trial.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that COX-2 may be a predictive marker of early relapse in with DCIS and may aid the clinical decision-making process for treatment of DCIS. Using two independent cohorts, we have shown that assessment of COX-2 expression in these tumours can be reliably performed using immunohistochemistry on paraffin-based tissues to identify tumour with high COX-2 expression.

Furthermore, the use of COX-2 inhibitors in association with aromatase inhibitors in ER-positive DCIS appears to have biological effect with reduced epithelial proliferation and COX-2 expression as shown in our proof-of-concept clinical trial. Thus, we have both biomarker and targeted agent to assess in prospective studies for high-risk DCIS.

The data on COX-2 expression in invasive breast cancer correlated significantly with diminished overall survival in patients treated with mastectomy and radiotherapy supports the hypostasis that the COX-2 phenotype is related to a more aggressive tumour behaviour and radioresistance (O'Connor et al, 2004). As the radioresistance is one of the major barriers to improve the free relapse and/or survival rate of breast cancer patients with regard to DCIS, and the COX-2 is usually overexpressed in breast cancer that may have a ‘radioresistance phenotype' (Lin et al, 2013), a clinical trial based on the combined used of COX-2 inhibitors and radiotherapy in COX-2+ve DCIS would be important and useful for its clinical relevance (Liu et al, 2003). However, considering the side effects of the COX-2 inhibitors, it would be possible to consider the association of the COX-2 inhibitor for a short time only during the radiotherapy with a double effect: (1) favouring the radiosensibility of the breast cancer cells, and (2) increasing clinical benefit for the patients with less toxicity related to the short exposure to the COX-2 inhibitor.

Acknowledgments

This study was partly funded by the Victorian Breast Cancer Research Consortium, the NHMRC, the Cancer Council Victoria, the Cancer Council Queensland, the Victorian Cancer Biobank and Cancer Research UK and Oxford NHS Biomedical Research Centre. We also acknowledge the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre, UK, and Associazione Ricerca in Campo Oncologico Onlus, Cremona, Italy.

Author contributions

DG, SD, SBF, ALH and SRL helped in writing the manuscript; MC, LER, RG and DB helped in reviewing slides to confirm diagnosis; AB, GA and MM helped in collecting data from the trials; FMB, MT and DA helped in statistical analysis.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website (http://www.nature.com/bjc)

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Material

References

- Barnes NL, Warnberg F, Farnie G, White D, Jiang W, Anderson E, Bundred NJ. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition: effects on tumour growth, cell cycling and lymphangiogenesis in a xenograft model of breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2007;96 (4):575–582. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijker N, Meijnen P, Peterse JL, Bogaerts J, Van Hoorebeeck I, Julien JP, Gennaro M, Rouanet P, Avril A, Fentiman IS, Bartelink H, Rutgers EJ. Breast-conserving treatment with or without radiotherapy in ductal carcinoma-in-situ: ten-year results of European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer randomized phase III trial 10853—a study by the EORTC Breast Cancer Cooperative Group and EORTC Radiotherapy Group. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24 (21):3381–3387. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boland GP, Butt IS, Prasad R, Knox WF, Bundred NJ. COX-2 expression is associated with an aggressive phenotype in ductal carcinoma in situ. Br J Cancer. 2004;90 (2):423–429. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottini A, Berruti A, Bersiga A, Brizzi MP, Brunelli A, Gorzegno G, DiMarco B, Aguggini S, Bolsi G, Cirillo F, Filippini L, Betri E, Bertoli G, Alquati P, Dogliotti L. p53 but not bcl-2 immunostaining is predictive of poor clinical complete response to primary chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6 (7):2751–2758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottini A, Generali D, Brizzi MP, Fox SB, Bersiga A, Bonardi S, Allevi G, Aguggini S, Bodini G, Milani M, Dionisio R, Bernardi C, Montruccoli A, Bruzzi P, Harris AL, Dogliotti L, Berruti A. Randomized phase II trial of letrozole and letrozole plus low-dose metronomic oral cyclophosphamide as primary systemic treatment in elderly breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24 (22):3623–3628. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.5773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffa FM, Camps C, Winchester L, Snell CE, Gee HE, Sheldon H, Taylor M, Harris AL, Ragoussis J. microRNA-associated progression pathways and potential therapeutic targets identified by integrated mRNA and microRNA expression profiling in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71 (17):5635–5645. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bundred NJ, Cramer A, Morris J, Renshaw L, Cheung KL, Flint P, Johnson R, Young O, Landberg G, Grassby S, Turner L, Baildam A, Barr L, Dixon JM. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition does not improve the reduction in ductal carcinoma in situ proliferation with aromatase inhibitor therapy: results of the ERISAC randomized placebo-controlled trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16 (5):1605–1612. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang SH, Liu CH, Conway R, Han DK, Nithipatikom K, Trifan OC, Lane TF, Hla T. Role of prostaglandin E2-dependent angiogenic switch in cyclooxygenase 2-induced breast cancer progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101 (2):591–596. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2535911100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow LW, Yip AY, Loo WT, Lam CK, Toi M. Celecoxib anti-aromatase neoadjuvant (CAAN) trial for locally advanced breast cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;111 (1-2):13–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies G, Salter J, Hills M, Martin LA, Sacks N, Dowsett M. Correlation between cyclooxygenase-2 expression and angiogenesis in human breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9 (7):2651–2656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirix LY, Ignacio J, Nag S, Bapsy P, Gomez H, Raghunadharao D, Paridaens R, Jones S, Falcon S, Carpentieri M, Abbattista A, Lobelle JP. Treatment of advanced hormone-sensitive breast cancer in postmenopausal women with exemestane alone or in combination with celecoxib. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26 (8):1253–1259. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.3744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group (EBCTCG), Correa C, McGale P, Taylor C, Wang Y, Clarke M, Davies C, Peto R, Bijker N, Solin L, Darby S. Overview of the randomized trials of radiotherapy in ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2010;2010 (41):162–177. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher B, Dignam J, Wolmark N, Wickerham DL, Fisher ER, Mamounas E, Smith R, Begovic M, Dimitrov NV, Margolese RG, Kardinal CG, Kavanah MT, Fehrenbacher L, Oishi RH. Tamoxifen in treatment of intraductal breast cancer: National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-24 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 1999;353 (9169):1993–2000. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)05036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox SB, Generali D, Berruti A, Brizzi MP, Campo L, Bonardi S, Bersiga A, Allevi G, Milani M, Aguggini S, Mele T, Dogliotti L, Bottini A, Harris AL. The prolyl hydroxylase enzymes are positively associated with hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha and vascular endothelial growth factor in human breast cancer and alter in response to primary systemic treatment with epirubicin and tamoxifen. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13 (1):R16. doi: 10.1186/bcr2825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Generali D, Buffa FM, Berruti A, Brizzi MP, Campo L, Bonardi S, Bersiga A, Allevi G, Milani M, Aguggini S, Papotti M, Dogliotti L, Bottini A, Harris AL, Fox SB. Phosphorylated ERalpha, HIF-1alpha, and MAPK signaling as predictors of primary endocrine treatment response and resistance in patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27 (2):227–234. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.7083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Half E, Tang XM, Gwyn K, Sahin A, Wathen K, Sinicrope FA. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression in human breast cancers and adjacent ductal carcinoma in situ. Cancer Res. 2002;62 (6):1676–1681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane RL, Virnig BA, Shamliyan T, Wang SY, Tuttle TM, Wilt TJ. The impact of surgery, radiation, and systemic treatment on outcomes in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2010;2010 (41):130–133. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearney PM, Baigent C, Godwin J, Halls H, Emberson JR, Patrono C. Do selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors and traditional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs increase the risk of atherothrombosis? Meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ. 2006;332 (7553):1302–1308. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7553.1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerlikowske K, Molinaro AM, Gauthier ML, Berman HK, Waldman F, Bennington J, Sanchez H, Jimenez C, Stewart K, Chew K, Ljung BM, Tlsty TD. Biomarker expression and risk of subsequent tumors after initial ductal carcinoma in situ diagnosis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102 (9):627–637. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leake R, Barnes D, Pinder S, Ellis I, Anderson L, Anderson T, Adamson R, Rhodes T, Miller K, Walker R. Immunohistochemical detection of steroid receptors in breast cancer: a working protocol. UK Receptor Group, UK NEQAS, The Scottish Breast Cancer Pathology Group, and The Receptor and Biomarker Study Group of the EORTC. J Clin Pathol. 2000;53 (8):634–635. doi: 10.1136/jcp.53.8.634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard GD, Swain SM. Ductal carcinoma in situ, complexities and challenges. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96 (12):906–920. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin F, Luo J, Gao W, Wu J, Shao Z, Wang Z, Meng J, Ou Z, Yang G. COX-2 promotes breast cancer cell radioresistance via p38/MAPK-mediated cellular anti-apoptosis and invasiveness. Tumour Biol. 2013;34 (5):2817–2826. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0840-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Chen Y, Wang W, Keng P, Finkelstein J, Hu D, Liang L, Guo M, Fenton B, Okunieff P, Ding I. Combination of radiation and celebrex (celecoxib) reduce mammary and lung tumor growth. Am J Clin Oncol. 2003;26 (4):S103–S109. doi: 10.1097/01.COC.0000074147.22064.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre A, Patiar S, Wigfield S, Li JL, Ledaki I, Turley H, Leek R, Snell C, Gatter K, Sly WS, Vaughan-Jones RD, Swietach P, Harris AL. Carbonic anhydrase IX promotes tumor growth and necrosis in vivo and inhibition enhances anti-VEGF therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18 (11):3100–3111. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McShane LM, Altman DG, Sauerbrei W, Taube SE, Gion M, Clark GM. Reporting recommendations for tumor marker prognostic studies. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23 (36):9067–9072. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.0454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohsin SK, Weiss H, Havighurst T, Clark GM, Berardo M, Roanh le D, To TV, Qian Z, Love RR, Allred DC. Progesterone receptor by immunohistochemistry and clinical outcome in breast cancer: a validation study. Mod Pathol. 2004;17 (12):1545–1554. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokbel K, Cutuli B. Heterogeneity of ductal carcinoma in situ and its effects on management. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7 (9):756–765. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70861-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor JK, Avent J, Lee RJ, Fischbach J, Gaffney DK. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression correlates with diminished survival in invasive breast cancer treated with mastectomy and radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58 (4):1034–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ristimaki A, Sivula A, Lundin J, Lundin M, Salminen T, Haglund C, Joensuu H, Isola J. Prognostic significance of elevated cyclooxygenase-2 expression in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62 (3):632–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spizzo G, Gastl G, Wolf D, Gunsilius E, Steurer M, Fong D, Amberger A, Margreiter R, Obrist P. Correlation of COX-2 and Ep-CAM overexpression in human invasive breast cancer and its impact on survival. Br J Cancer. 2003;88 (4):574–578. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takkouche B, Regueira-Mendez C, Etminan M. Breast cancer and use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100 (20):1439–1447. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan EY, Yan M, Campo L, Han C, Takano E, Turley H, Candiloro I, Pezzella F, Gatter KC, Millar EK, O'Toole SA, McNeil CM, Crea P, Segara D, Sutherland RL, Harris AL, Fox SB. The key hypoxia regulated gene CAIX is upregulated in basal-like breast tumours and is associated with resistance to chemotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2009;100 (2):405–411. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wapnir IL, Dignam JJ, Fisher B, Mamounas EP, Anderson SJ, Julian TB, Land SR, Margolese RG, Swain SM, Costantino JP, Wolmark N. Long-term outcomes of invasive ipsilateral breast tumor recurrences after lumpectomy in NSABP B-17 and B-24 randomized clinical trials for DCIS. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103 (6):478–488. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou H, Hastie T. Regularization and variable selection via the elastic net. J R Statist Soc B. 2005;67 (part 2):301–320. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.