Abstract

India is among the countries that are worse affected by human malaria, one of the major vector-borne diseases that continue to affect vast populations across the world. In a recent household survey in the Terai region of eastern India, the factors that might explain the occurrence and clustering of human malaria and the consequent healthcare-seeking behaviour of the human population were explored. The topography and geo-climatic conditions in Terai appear to intensify the risks of malaria but some socio–economic attributes, such as engagement in agricultural occupations, poor economic status and congested household environments, were also identified as significant risk factors for the disease. In the study area, public health facilities predominate as sources of medical care for malaria, although, at least in the early stages of treatment seeking, informal providers and pharmacies are also often involved. Unfortunately, despite the high frequency of malarial outbreaks, the local public health facilities were found to be ill-equipped to tackle and contain the spread of malaria. Preventive public-health measures, health education on malaria and malaria-awareness exercises were found to be scarce and irregular. The reliance on a reactive strategy of offering curative care to the affected led to overcrowding in healthcare facilities and shortages of medicines and diagnostic procedures. Along with a more efficient and reliable emergency system to deal with major outbreaks of malaria, more effective convergent interventions, by the local government and other stakeholders, should be developed to help prevent the disease.

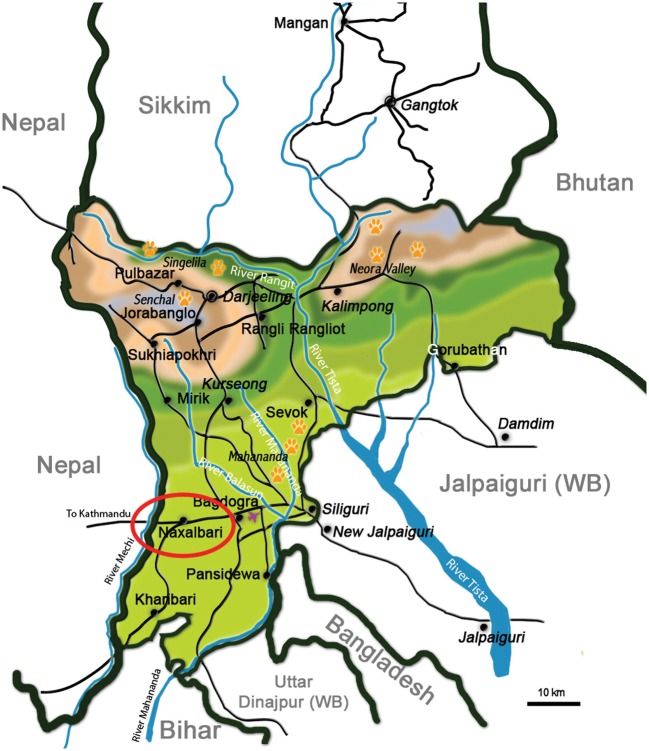

Despite continued efforts by health systems globally to contain its spread and the morbidity and mortality it causes, human malaria remains a major vector-borne disease across the developing world. It continues to be one of the world’s most lethal diseases, with half the world’s population — about 3300 million people — considered to be at risk from it (WHO, 2009). In India, although there has been some recent reduction in the incidence of malaria, the annual number of cases remains huge and represents more than three-quarters of the number occurring throughout South–east Asia (WHO, 2009). Malaria in India is concentrated in a few states and then mostly in pockets within the worst-affected states, with Orissa (25%), Chattisgarh (13%), West Bengal (11%), Jharkhand (7%) and Karnataka (7%) together accounting for the major share of the official malaria burden (Kumar et al., 2007). Much of the burden of malaria in India probably remains ‘invisible’, however, with the official estimates heavily reliant on government records of malaria-attributable deaths (Hay et al., 2010). In their recent study, Dhingra et al. (2010) found that malaria-related mortality in India was markedly higher that the latest ‘official’ estimate of the World Health Organization. The public-health statistics available from government agencies in India also fail to capture, and hence provide an understanding of, the various aspects of the social epidemiology of the disease and consequent treatment-seeking patterns. The aim of the present study was to explore the (self-reported) prevalence of malaria, the associated socio–economic differentials and the associated treatment-seeking behaviour in one of the malaria-endemic areas of north–eastern India: part of the Terai region that lies within Darjeeling district, in the eastern state of West Bengal (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Map showing the locations of the district of Darjeeling, within the Indian state of West Bengal (WB), and the study area (circled in red).

The ‘Terai’ (or ‘moist land’) is a 38-km-long north–south belt of marshy grasslands, savannah and forests at the base of the Himalaya range, including the plains of Darjeeling district, the whole of Jalpaiguri district and the north of Cooch Behar district. An area dotted with tea plantations, tropical evergreen forests and perennial streams, the Terai region accounts for >60% of malaria cases recorded in West Bengal (Anon., 2007). In the Terai plains of Darjeeling district, malaria is endemic in three community-development blocks and it was one of these blocks, Naxalbari (2001 population = 144,915), that was the area investigated in the present study (Fig. 1). Naxalbari lies in the foothills of the Himalayas, at 26°38′–26°49′N, 88°10′–88°22′E, and a mean altitude of 152 m above sea level. The annual mean maximum and minimum air temperatures in the block are 32°C and 15°C, respectively, while mean annual rainfall is about 3000 mm (Sharma et al., 2009a). The block is largely underdeveloped, and its public utilities and infrastructure are rudimentary in form. It suffers from regular, periodic malaria epidemics. The healthcare needs of the population are largely covered by 17 primary-healthcare units, a few rudimentary tea-garden dispensaries and a rural hospital.

There have been few studies on the epidemiology of malaria in Naxalbari or on the related socio–demographic characteristics of the block’s human population. Sharma et al. (2009b) investigated the epidemiology of a massive outbreak of malaria in Naxalbari in 2005, however, and similar studies have been conducted elsewhere in West Bengal (Malakar et al., 1995) and in other parts of India (Yadav et al., 2003; Dutta et al., 2004; Dev et al., 2006). The focus of these studies has been on antimalarial prophylaxis, the determinants of the (reported) incidence of malaria, and/or the effectiveness of various treatment regimens (chloroquine, primaquine, artemisinin-based combination therapy etc). There has been relatively little exploration of treatment-seeking behaviours following a major outbreak of malaria in India, or of how well the local health system responds to a post-outbreak surge in demand for curative care and adheres to effective therapies. Chaturvedi et al. (2009) did, however, investigate treatment-seeking in malaria-endemic districts of the Indian state of Assam, and this aspect of malaria has been investigated in several studies in Africa and Asia (McCombie, 1996; Tanner and Vlassof, 1998; Uzochukwu and Onwujekwe, 2004).

The focus of the present study was treatment-seeking behaviour for malaria in Naxalbari block. An understanding of the possible determinants of a malaria epidemic, and, perhaps more importantly, an understanding of health-service utilization by the local people when they are faced with a malaria outbreak, can help to guide public-health interventions and detect the lacunae in the existing mechanisms for healthcare delivery. In many regions of India, the responses of public health systems to such crises are often timid, and lack a proper assessment of the demand for services. Unqualified medical practitioners, who are commonly found in rural settings across the country, often serve as important agents and initial points of contact for malaria cases. If national/regional policies allowed it, such practitioners could serve as alternative channels of service delivery for national or regional programmes of malaria control.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

The present, largely descriptive study formed part of a larger household survey carried out in rural areas of selected districts in West Bengal between the June and August of 2006 (Mazumdar and Guruswamy, 2009). The larger survey was primarily designed to explore the economics of healthcare, particularly in terms of the demand, utilization and perceived quality of healthcare services for malaria and diarrhoea. This paper reports the findings from the analysis of the survey data covering two villages in Naxalbari block — data collected 6–10 months after a massive outbreak of malaria in the block (Sharma et al., 2009b).

In the survey, a semi-structured schedule was used to elicit responses, from an adult member of each selected household, regarding the incidence, severity and treatment of malaria. An interpreter was employed, as most of the villages and communities investigated were dominated by Nepali and Sadri-speaking households. Estimates of the prevalence of malaria and observations on treatment-seeking were based entirely on the reports of the respondents and did not involve any supporting clinical confirmation. Although, ideally, the collected data should have been cross-checked against hospital and/or treatment records, only a small proportion of the selected households held any relevant records (e.g. out-patient cards, discharge certificates and prescriptions).

The survey instruments were cleared by the doctoral research committee of the International Institute for Population Sciences in Mumbai, and informed consent was sought from the respondents before initiating interviews.

The sub-sample for Naxalbari comprised of 120 households selected through multi-stage random sampling. In the first stage of sampling, a gram panchayat was selected at random (Hatighisha) and then two census villages (Nandalal and Sebdella) were randomly selected from that gram panchayat (a gram panchayat represents the lowest tier of locally elected government in India— roughly corresponding to a group of revenue or census villages — and serves as the prifmary level in the administrative hierarchy). Systematic random sampling was then used to select 55 study households in Nandalal and 65 in Sebdella.

Statistical tests for significance of associations were applied as required.

RESULTS

Although the results are only broadly indicative, and should be interpreted accordingly, they do highlight some of the key issues that characterise malaria and its treatment in many endemic areas.

The study households together held 636 villagers, including 139 individuals who reportedly suffered from malaria in the 12 months prior to the interviews, indicating a (self-reported) annual incidence of about 220 cases/1000 residents. The Table shows the reported prevalences of malaria in the two study communities split by certain socio–economic and demographic parameters. Malaria appeared to be relatively common in households with few rooms (perhaps leading to overcrowding and sharing rooms with livestock) and in households whose members were primarily engaged in agriculture (as self-employed farmers or waged labourers). There was no clear evidence of a significant association between the occurrence of malaria in a household and the economic status of the household or the ages of its members.

The prevalences of malaria among the 636 villagers of Nandalal and Sebdella (as reported for the 12 months prior to the interviews), split by the ages, educational levels, castes and household characteristics of the villagers.

| Prevalence | ||

| Variable | (% of group) | Pearson’s χ2 |

| age (years) | 1·9449 | |

| 0–4 | 14·6 | |

| 5–14 | 22·9 | |

| 15–59 | 22·6 | |

| ⩾60 | 21·1 | |

| level of education | 7·1396 | |

| Illiterate | 27·2 | |

| Less than primary | 17·6 | |

| Middle school (Standard VIII) | 18·6 | |

| Completed secondary school | 25·0 | |

| Higher secondary and above | 23·1 | |

| caste | 5·3265 | |

| General | 18·0 | |

| Scheduled caste | 26·8 | |

| Scheduled tribe | 20·5 | |

| Other backward class | 17·5 | |

| household size (no. of rooms) | 8·1267* | |

| 1 | 22·2 | |

| 2 | 27·0 | |

| >2 | 16·5 | |

| major source of household income | 20·739* | |

| Cultivation | 24·8 | |

| Agricultural labour | 28·8 | |

| Non-agricultural labour | 17·8 | |

| Government/private service | 8·2 | |

| Business/self-employment | 9·3 | |

| quintile for monthly per capita consumption expenditure | 16·239* | |

| 1 (poorest) | 26·4 | |

| 2 | 18·1 | |

| 3 | 16·5 | |

| 4 | 32·8 | |

| 5 (richest) | 16·2 |

*P<0·05.

In a partial correlation matrix involving the background attributes included in the Table, only one statistically significant correlation coefficient was observed: that between the length of time an individual had spent in formal education (in years) and mean monthly per-capita expenditure (in rupees) (r = 0·62).

Medical records for only 31 of the malaria cases were seen in the household survey. Almost all of these documents (which could be used to validate some of the respondents’ reports) were discharge certificates provided by the rural hospital and had malaria (either Plasmodium vivax or P. falciparum) mentioned as the disease. The symptoms described by the respondents, for each of the malaria cases considered here, did, however, match a list of the ‘classical’ symptoms of malaria (prepared in consultation with government physicians from the rural hospital), and every reported case of suspected malaria whose blood was checked for malarial parasites was apparently found parasitaemic.

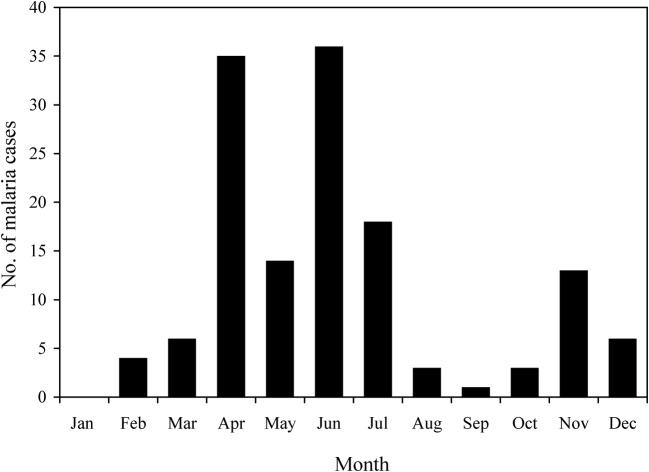

In the study villages, most of the malaria cases that were reported to have occurred in the 12 months prior to the interviews had occurred in the summer months of April–July (Fig. 2). Certain human behaviours and customs described in the interviews may be at least partly responsible for such seasonality in malaria incidence. During the early summer months, for example, the residents of Naxalbari block enter the nearby forests as they collect firewood or rear cattle (and are bitten by forest-dwelling mosquitoes). During the early monsoon, in the months of June and July, the transplantation of rice requires long hours of working in waterlogged conditions (and further exposure to mosquito bites). After the rainy season, another outbreak of malaria often occurs, the result of Anopheles mosquitoes breeding in the puddles in the waterlogged ground around the households. Figure 2 shows some evidence of such a post-rainy-season rise in malaria incidence (i.e. the 13 cases reported to have occurred in the November prior to the interviews).

Figure 2.

The monthly distribution of reported malaria cases in Nandalal and Sebdella (based on data for the 12 months prior to the interviews).

In some of the villages in Naxalbari (particularly those having a higher proportion of Nepali-speaking households), a typical house is two-storied and generally made of wood, with cattle kept on the ground floor and the family living on the first floor. The livestock in the house probably attract mosquitoes while the wooden structure leaves holes through which mosquitoes can pass and in which mosquitoes can rest.

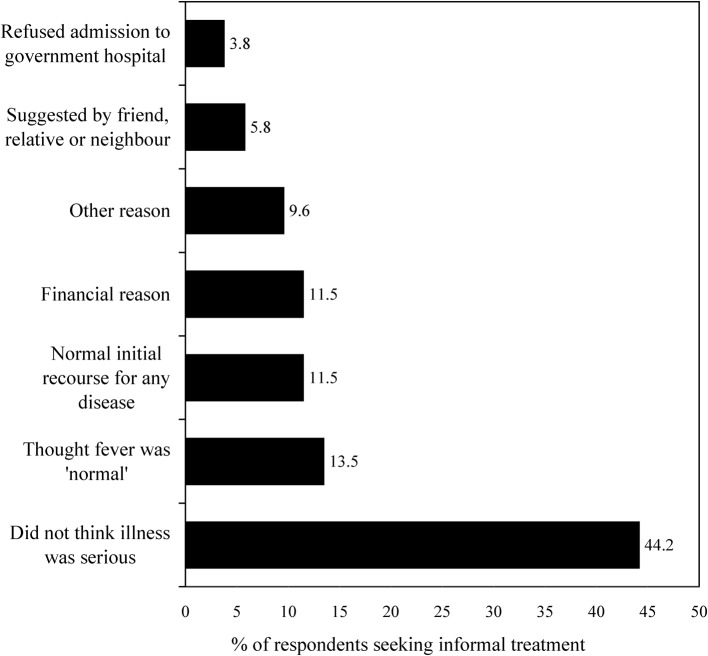

Treatment-seeking Behaviour for Malaria: Utilization of Informal Providers

Of the 139 reported cases of malaria, 41 (29%) initially sought treatment from an informal provider (Fig. 3), either consulting allopathic quacks who practised within their home village, or self-medicating with drugs purchased across the counter from pharmacies or from weekly marketplaces (haats). Most of the cases who had initially followed this ‘casual’ route to treatment had often misidentified their malarial symptoms as those of some less serious illness. Some had followed an informal route to treatment because they believed it would be cheaper [even though informal providers are not necessarily a low-cost option in India (Kanjilal et al., 2007; Mazumdar, 2008)]. At times, the lack of preparedness of the local government health facilities had reportedly forced some malaria cases to choose informal providers of healthcare.

Figure 3.

The reasons given for seeking informal treatment for malaria. ‘Other’ reasons include lack of confidence in the treatment available in public facilities, and inability to gain the approval and permission of the head of household (because he was absent).

The median and mean durations of informal treatment for malaria were 3 days and about 5 days, respectively. Such treatment generally led to no improvement (31 cases) but six cases claimed to have received some relief (mostly the temporary remission of fever) and four cases claimed to have been cured by informal treatment.

Utilization of Qualified Providers in Public and Private Facilities

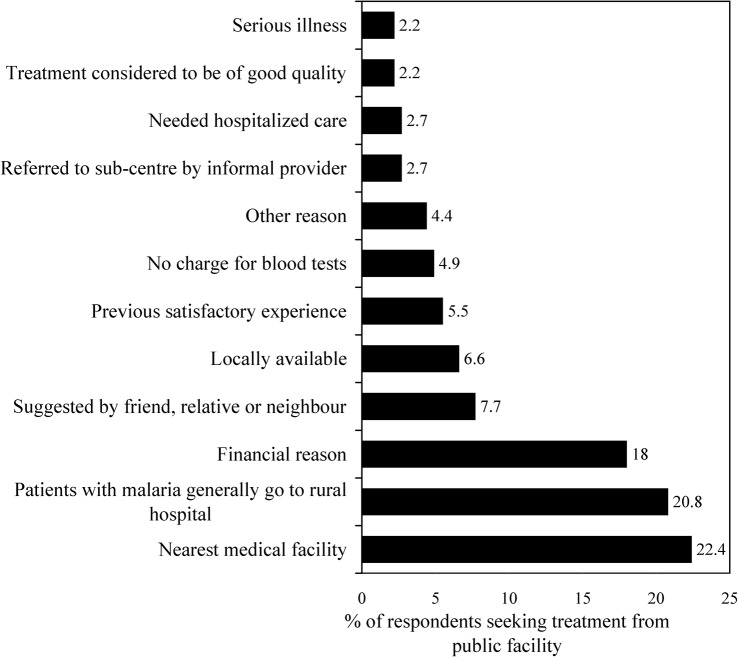

Of the reported cases of malaria, 129 (92%) resorted to formal care from qualified providers (either initially or after informal care had failed). Most (84% of the formal-treatment seekers) sought treatment from the nearest major source of formal healthcare: Naxalbari Rural Hospital. Only four cases went to private allopathic health providers for treatment.

Figure 4 presents the reasons behind seeking care from public facilities, the dominant providers in the study area. The major reasons for treatment-seeking from public facilities were proximity (of the rural hospital; 22%), the general preference of presumed malaria cases (i.e. individuals suffering from similar symptoms to the case) in the case’s home community (21%) and financial (with most healthcare in the hospital given free of charge; 18%).

Figure 4.

The reasons given for seeking formal treatment for malaria from public facilities. ‘Other’ reasons include being taken to the rural hospital by a gram panchayat member, and the perception that public facilities offered a faster cure than the other treatment options.

Only one case sought care from private facilities because he felt that treatment was not readily available at the public hospital. Another case felt that treatment in private facilities was of better quality than public treatment. Overall, however, very few of the cases resorted to private care, and mostly did so because of their satisfactory previous experience of such care or because the facility or provider was located nearby.

Most cases who sought formal treatment only after informal treatment had failed were ill enough when that arrived at a formal healthcare facility to need hospitalization. Overall, 63% of the malaria cases who sought formal care from public facilities and three of the cases who sought such care from private sources were immediately referred for hospitalized care. At some stage, the Naxalbari Rural Hospital admitted almost nine out of every 10 cases investigated in the present study, making this facility the most important local source of treatment for malaria. In-patient care from a public hospital was not, however, always considered a desirable option for a malaria case. One of the respondents (a 43-year-old, male and illiterate casual worker in a tea-garden, who belonged to a scheduled tribe and was of low economic status) stated:

‘My child was suffering from high fever, chills and rigors from the night. I took her to the Naxalbari hospital in the morning. The doctors suggested that my daughter needs to be hospitalized. There was no place available for new admission. All the beds were occupied; some beds were even occupied by more than one patient. I was helpless, since I did not have enough money to take her to the private hospitals at Siliguri. My child was kept outside the hospital for 2 days and was treated under the temporary arrangement made by the doctors.’

With such almost universal reliance on, and high utilization of, the services offered by the local rural hospital, the hospital and the rest of the public healthcare system clearly need to respond adequately and effectively to the needs of the malaria cases and deliver quality services.

Blood Tests for Malaria

Although the presumptive treatment of malaria is common in many endemic areas, the World Health Organization recommends that a health provider who is faced with a possible case of malaria should request immediate blood tests to confirm the presence and species of malarial parasite in the patient’s body (WHO, 2010). According to the respondents in the present study, blood tests were immediately requested for almost all of the malaria cases seen by formal healthcare providers — 96% of those treated at public facilities and 100% of those treated at private facilities. Most of the cases who sought treatment at public hospitals underwent blood tests at the same hospitals but some were compelled to get the tests done by private laboratories (because the public hospital had a very long waiting list for blood tests and/or had no laboratory technician present when the case needed testing). In one of the interviews, a 45-year-old, male daily wage earner, who belonged to a scheduled tribe, was educated up to Standard-VII level and was of low economic status, reported:

‘My wife had malaria and I took her to the Naxalbari [Rural] Hospital. The doctors told me that blood test was not possible that day, as it was evening and the technician had left. They also told me that if I get the test done [at the hospital on the] next morning, I would get the report only after 24 hours. My wife was seriously ill, and the doctors advised me to have the test done from outside [i.e. by a private laboratory]. I got the blood test done at one of the clinics, and they gave me the report next morning. If I had waited for the test to be done from hospital, I would not have received the report then…’

Many cases reported how, even after bloodsmears had been prepared, there was a considerable delay in the transmission of the results of the blood testing to the relevant clinician (with mean delays of about 12 h in private facilities, <24 h in local medical camps, set up for the detection of cases during outbreaks, and 32 h in public facilities). About 25% of the cases whose blood was collected for malaria diagnosis did not know the results of their blood tests (because they were tested in public facilities where the delivery of a written report detailing the presence or absence of malarial parasites in the patient’s blood was not considered necessary).

Availability of Medicines

Almost all the malaria cases reported that antimalarial medicines were prescribed immediately after blood samples were collected, before the result of any blood tests were known. Most appropriate drugs are supplied under the National Vector-borne Disease Control Programme (NVDCP) and should be freely available to malaria cases coming for treatment in any public facility. Only about half the cases who visited public hospitals received antimalarial drugs from the hospitals, however, and 45% of such cases had to procure antimalarial drugs from private drug stores (because of bottlenecks in the supply of such drugs to public health facilities).

According to the data recorded in the interviews, of every four malaria cases who sought initial treatment for malaria from a formal provider, three were completely cured and one showed a post-treatment relapse. All 37 cases who relapsed sought further treatment, either from the rural hospital where they had received their first round of treatment or (in a few cases, to avoid a second visit to the rural hospital) from local pharmacies (where cases bought the same drugs that they had used in the failed first round of treatment).

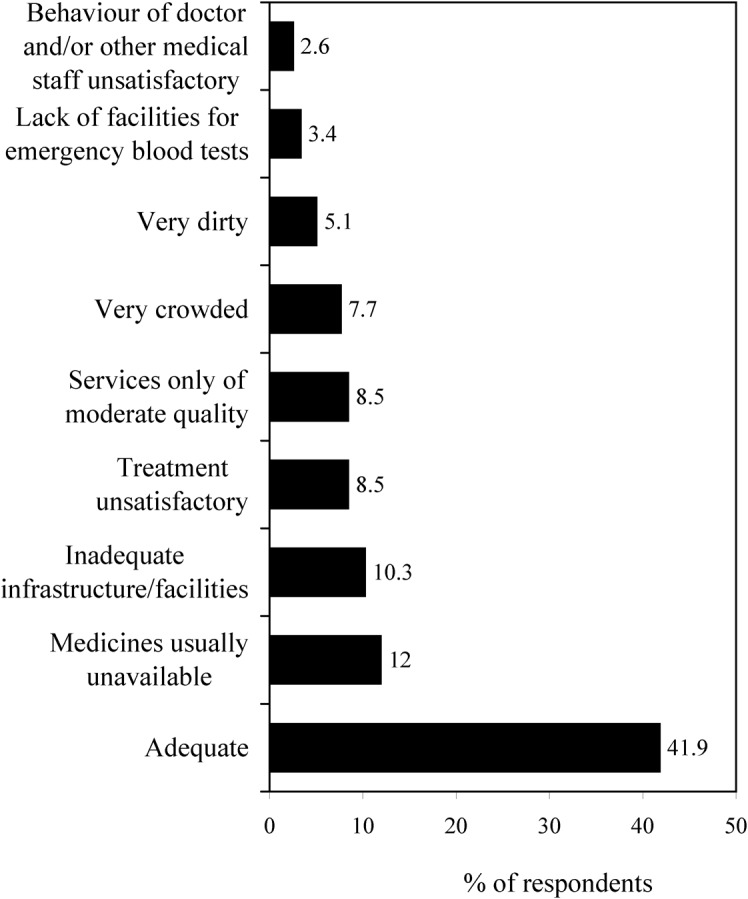

Opinion about the Treatment Facilities in Public Hospitals

The opinions of the respondents about malaria-treatment facilities in the rural hospital were varied (Fig. 5). Although about half of the respondents considered the facilities to be adequate or of ‘medium’ quality, 10% regarded the facilities to be inadequate, and about 15% were disappointed by the lack of medicines and other required infrastructure (such as blood-testing facilities). Most (58%) of the malaria cases interviewed were each aware of at least one measure for the prevention of malaria, usage of bednets at night being the commonest measure described, followed by keeping households and their surroundings clean.

Figure 5.

The respondents’ opinions of the malaria-treatment facilities at Naxalbari Rural Hospital.

DISCUSSION

The broad findings of the present study are two-fold. Firstly, as previously observed by Sharma et al. (2009b), human malaria is endemic in Naxalbari block. At the time of the interviews, almost a quarter of the study population had experienced at least one episode of the disease in the previous 12 months [although this period did include the major outbreak of malaria in Naxalbari described by Sharma et al. (2009b)].

Secondly, many of the local cases of malaria initially seek medical treatment from informal providers, and, after showing little if any improvement (and, often, considerable deterioration), then seek treatment from the local public hospital. Although the public hospital is the preferred choice for the treatment of local malaria cases, it is not sufficiently well-equipped to cater to all of the cases’ needs effectively. Although malaria diagnosis and antimalarial treatment are, in theory, freely available at the public hospital — and the staff at the hospital must be aware that malaria is common in the hospital’s catchment area — in practice, malaria cases (or their families) often feel forced to pay for private blood tests and antimalarial drugs. There appeared to be no good evidence of a broad-based public-health response to the burden of malaria in the study area. Some local gram panchayats organize intermittent exercises involving the spraying of insecticides and fumigants, or the distribution of insecticide-treated bednets (unpubl. obs.) but — in the absence of a clear preventive healthcare policy or any major attempt to generate better awareness among the villagers — these interventions appear to be insufficient to prevent malaria outbreaks.

As a natural consequence of the failure to prevent malaria outbreaks in a pro-active manner, government health facilities consistently hang on to a reactive strategy in which they offer (or, at least, try to offer) curative care to large numbers of malaria cases. The resultant overcrowding and overstretching seriously hamper the delivery by government health facilities of high-quality services that are based on patients’ needs, with poor planning and supply-chain management often leading to shortages of antimalarial drugs and round-the-clock facilities for blood tests. At the rural hospital in Naxalbari, medical staff including doctors could only provide limited support, especially when seasonal peaks in local malaria incidence (which are predictable; Baruah et al., 2007) occurred. If the local government could develop more rigorous public-health measures for the prevention of malaria, the general incidence of the disease might fall to a level that could be managed well by the rural hospital, with sufficient scope and preparedness to deal with any outbreaks.

The public-health challenge posed by the frequent ‘waves’ of malaria in Naxalbari is aggravated by the overall development scenario in the region. Employment is mostly in the unorganized sector, such as share-cropping, landless labour or temporary work in the tea plantations in the area, and poverty is wide-spread. Villages are often quite isolated and become difficult to access during monsoons or at night. As seen previously in Naxalbari and elsewhere in India (Das et al., 2007; Sharma et al., 2009b), villagers engage in behaviours and working patterns that increase their exposure to vector mosquitoes.

A more focussed approach by the public facilities and health system at large, involving intensive health education and the promotion of practices that can significantly reduce the high burden posed by malaria in the area, is required to bring down the periodic surges in malaria cases in Naxalbari. If the case loads at local health facilities can be markedly reduced, the resources to administer treatment of better quality and efficacy should become available.

Acknowledgments

The paper is a part of the author’s doctoral thesis at the International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai. The author is indebted to P. G. Mazumdar, for her painstaking efforts during the fieldwork, and M. Guruswamy, for his numerous discussions and editing. Valuable comments on the study design and concepts were provided by S. Mohanty, C. Sekhar and S. S. Narvekar. The excellent assistance of P. Kumar Chettry, the help extended by B. Ghosh and S. Oraon and the kind co-operation of the villagers of Hatighisha are also gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- Anon(2007)Health on the March, 2006–07 Kolkata, India: Department of Health and Family Welfare [Google Scholar]

- Baruah I, Das NG, Kalita J.(2007)Seasonal prevalence of malaria vectors in Sonitpur district of Assam, India. Journal of Vector Borne Diseases 44149–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi HK, Mahanta J, Pandey A.(2009)Treatment-seeking for febrile illness in north–east India: an epidemiological study in the malaria endemic zone. Malaria Journal 8301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das NG, Talukdara PK, Kalita J, Baruah I, Srivastava RB.(2007)Malaria situation in forest-fringed villages of Sonitpur district (Assam), India bordering Arunachal Pradesh during an outbreak. Journal of Vector Borne Diseases 44213–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dev V, Dash AP, Khound K.(2006)High-risk areas of malaria and prioritizing interventions in Assam. Current Science 9032–36. [Google Scholar]

- Dhingra N, Jha P, Sharma VP, Cohen AA, Jotkar RM, Rodriguez PS, Bassani DS, Suraweera W, Laxminarayan R, Peto R.(2010)Adult and child malaria mortality in India: a nationally representative mortality survey. Lancet 3761768–1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta J, Singh Z, Verma AK, Bishnoi MS.(2004)Malaria — resurgence and problems. Indian Journal of Community Medicine 29171–172. [Google Scholar]

- Hay SI, Gething PW, Snow RW.(2010)India’s invisible malaria burden. Lancet 3761716–1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanjilal B, Mondal S, Samanta T, Mondal A, Singh S.(2007)A Parallel Healthcare Market: Rural Medical Practitioners in West Bengal, India Jaipur, India: Institute of Health Management Research [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Valecha N, Jain T, Dash AP.(2007)Burden of malaria in India: retrospective and prospective view. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 77(Suppl. 6)69–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malakar P, Das S, Saha GK, Dasgupta B, Hati AK.(1995)Indoor resting anophelines of north Bengal. Indian Journal of Malariology 3224–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazumdar S.(2008)The economics of health care in rural West Bengal: demand, utilization and quality of health services. Ph.D. thesis, International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai, India [Google Scholar]

- Mazumdar S, Guruswamy M.(2009)Demand and willingness to pay for healthcare in rural West Bengal. Social Change 3954 [Google Scholar]

- McCombie S.(1996)Treatment seeking for malaria: a review of recent research. Social Science and Medicine 43933–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma PK, Ramakrishnan R, Hutin YJ, Gupte MD.(2009a)Increasing incidence of malaria in Kurseong, Darjeeling district, West Bengal, India, 2000–2004. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 103691–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma PK, Ramakrishnan R, Hutin YJ, Sharma R, Gupte MD.(2009b)A malaria outbreak in Naxalbari, Darjeeling district, West Bengal, India, 2005: weaknesses in disease control, important risk factors. Malaria Journal 8288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner M, Vlassoff C.(1998)Treatment seeking behaviour for malaria: a typology based on endemicity and gender. Social Science and Medicine 46523–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzochukwu BSC, Onwujekwe OE.(2004)Socio–economic differences and health seeking behaviour for the diagnosis and treatment of malaria: a case study of four local government areas operating the Bamako initiative programme in south–east Nigeria. International Journal for Equity in Health 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization(2009)World Malaria Report 2009 Geneva: WHO [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization(2010)Guidelines for the Treatment of Malaria, 2nd Edn Geneva: WHO [Google Scholar]

- Yadav RS, Bhatt RM, Kohli VK, Sharma VP.(2003)The burden of malaria in Ahmedabad city, India: a retrospective analysis of reported cases and deaths. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology 97793–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]