Abstract

Young onset dementia is a challenge. We describe a case, where a patient presented with psychosis, dementia and MRI showing pulvinar sign, all of this typical of variant Cruetzfelt Jacob disease (CJD). Subsequent investigations lead to the diagnosis of a treatable illness and patient was improved and MRI sign reversed, underlining again the importance of search needed for treatable diseases in any “typical” case of fatal illness.

Keywords: Pulvinar sign, reversible, variant CJD, Wernicke's encephalopathy

Introduction

Young-onset dementia poses a challenge to physicians as many dementias are untreatable, while some are treatable, and the physician does not want to miss a dementia with a treatable cause. Here, we present a case that would have been easily misdiagnosed as a case of untreatable and fatal dementia illness.

Case Report

A 30-year-old man was admitted with a history of psychiatric complaints in the form of auditory and visual hallucinations for a 1-year duration, which was predominantly religious in nature, and, therefore, relatives did not realize that it was a part of the psychosis. Subsequently, the symptoms worsened, he became socially withdrawn, he excessively focused on prayers and neglected self-care and nutrition. About 3 months prior to admission, the patient stopped taking food completely and was taking only liquids, mostly plain water. Finally, when the illness reached a state that he could no longer live without total support of his relatives, he was taken to a hospital.

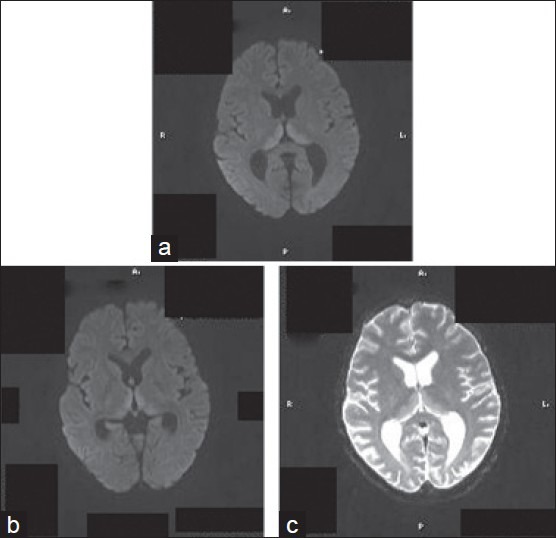

When the patient was seen by us, he was in an emaciated state and could barely stand, with two persons supporting him, and he could only produce incomprehensible sounds. He was unable to follow most commands and he had vertical nystagmus as well as uniform atrophy of all muscles. His deep tendon reflexes were sluggish and plantars were mute. He was investigated with routine blood tests and brain imaging. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain [Figure 1] showed bilateral thalamic hyperintensity on T2, FLAIR (Fluid attenuated inversion recovery) and diffusion images, which was reported as the “pulvinar sign” that was initially described in new variant CJD[1] [Figure 1]. His EEG Electroencephalogram [Figure 3] showed periodic triphasic waves. Therefore, his clinical profile and imaging of brain was well suiting for a diagnosis of new variant CJD.

Figure 1.

T2, FLAIR and Diffusion MR images showing high signal changes in the medial thalamus – the “pulvinar sign”

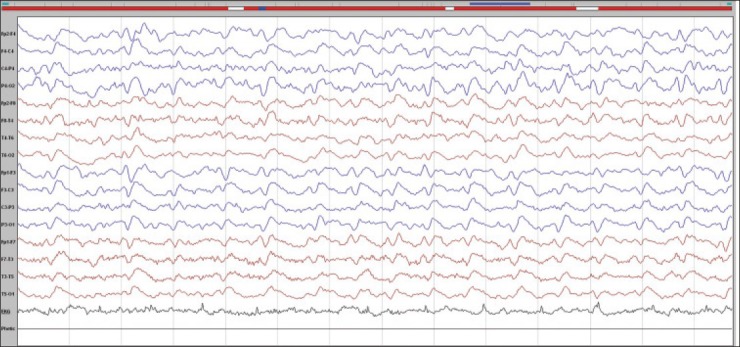

Figure 3.

EEG showing periodic triphasic pattern

As far as we knew, variant CJD had never been described from India so far. Therefore, we thought of alternate possibilities of “pulvinar” signs. Wernicke's encephalopathy (WE) was the closest differential in our patient in view of his poor nutritional status due to compulsive starvation.[2]

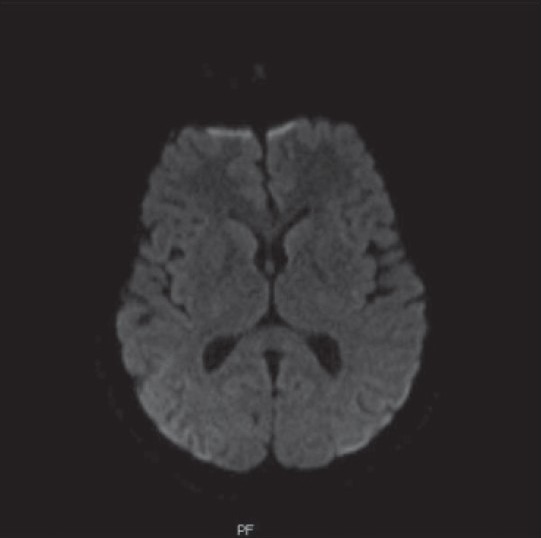

The patient was treated with high doses of thiamine and other B-complex vitamins and a high-protein diet. Over the next few weeks, the patient improved and became conscious and oriented. Vertical nystagmus also became improved. Subsequently, he was able to walk without support. He was discharged in that partially improved status. He was later seen in a follow-up outpatient clinic after about 2 months. At that time, he was neurologically normal. Repeat brain imaging [Figure 2] showed complete resolution of the thalamic lesions. We could not assess transketolase activity or cerebrospinal fluid 14-3-3. However, as the patient completely improved and the pulvinar sign in the MRI brain disappeared, we made a final diagnosis of WE on a background of psychosis in this patient.

Figure 2.

Diffusion image showing reversal of “pulvinar sign”

Discussion

Our patient demonstrated young-onset psychosis, rapidly progressive dementia and nystagmus. The differential diagnosis of psychosis with dementia in a young person is broad, but pulvinar signs in the MRI are considered as one of the core diagnostic features of variant CJD. Once the brain MRI shows a pulvinar sign, other differentials may be considered less likely. A “pulvinar sign” is rarely described in WE. Other possible radiological differentials of pulvinar signs include post-infectious demyelination, paraneoplastic[3] Fabry's disease[4] and thalamic infarction.

WE is a neurological complication of thiamine deficiency. It is characterized by mental confusion, opthalmoplegia and gait ataxia. WE is associated with conditions like chronic alcoholism, anorexia nervosa, hyperemesis gravidarum, prolonged fasting, HIV infection and dialysis. Patients with psychiatric disorders often have poor dietary habits, malnutrition and high prevalence of alcoholism, predisposing them to WE. Wernicke's symptoms may be overlooked or obscured by psychiatric illness.[5]

The regions of the brain that have been found to be pathologically involved in WE include mamillary bodies, periaqueductal regions, medial thalami, third ventricular walls, pons, medulla, basal ganglia and even cortical grey matter.[6] Typical MRI findings include increased T2 and FLAIR signal changes in areas around the aqueduct and third ventricle and also in the medial thalamus and mamillary bodies, at times with enhancement of mamillary bodies.[7] Brain atrophy and diffuse signal intensity changes in cerebral white matter can be imaging features in the chronic stage of WE. The pathologic changes that underlie acute WE lesions are complex and consist of mechanisms that could lead to ischemic-like changes in the thalami (i.e., cytotoxic edema or vasogenic edema). Thalamic hyperintensities on diffusion-weighted images could be due to restricted water diffusion in the lesion.[8]

EEG abnormalities are reported to occur in one-third of the patients with WE. The most common abnormality reported is theta slowing over the frontotemporal regions. However, EEG in WE showed non-specific changes, which can appear with many kinds of diffuse encephalopathy regardless of etiology.[9]

Our patient had young-onset psychosis. The patient had metabolic disturbances due to extreme degree of starvation, which led to the development of WE. As we could follow him up after about 2 months, we were able to demonstrate his clinical and radiological recovery.

Conclusion

Even though brain scans support a rare diagnosis, imaging should always be interpreted within the clinical context. Making a diagnosis of variant CJD has several consequences, including public health-related issues. Moreover, missing a treatable disease in a patient is detrimental. We presented this case to highlight the need for thoughtful diagnoses of treatable causes before making a diagnosis of v CJD when one sees “pulvinar” signs in an MRI of the brain.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil

References

- 1.Summers DM, Zeidler M, Will RG. The pulvinar sign in variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:446–7. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.3.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmidt C, Plickert S, Summers D, Zerr Pulvinar sign in Wernicke's encephalopathy. CNS Spectr. 2010;15:215–8. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900000043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mihara M, Sugase S, Konaka K, Sugai F, Sato T, Yamamoto Y, et al. The “pulvinar sign” in a case of paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis associated with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:882–4. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.049783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burlina AP, Manara R, Caillaud C, Laissy JP, Severino M, Klein I, et al. The pulvinar sign: Frequency and clinical correlations in Fabry disease. J Neurol. 2008;255:738–44. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-0786-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casanova MF. Wenricke's disease and schizophrenia: A case report and review of literature. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1996;26:319–28. doi: 10.2190/GD76-1UP3-TR18-YPYH. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yokote K, Miyagi K, Kuzuharas, Yumanouchi H, Yamada H. Wernicke encephalopathy, follow up study by CT and MRI. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1991;15:835–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abouaf L, Vighetto A, Magnin E, Nove-Josserand A, Mouton S, Tilikete C. Primary position upbeat nystagmus in Wernicke's encephalopathy. Eur Neurol. 2011;65:160–3. doi: 10.1159/000324329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.White ML, Zhang Y, Andrew LG, Hadley WL. MR imaging with diffusion weighted imaging in acute and chronic Wernicke encephalopathy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:2306–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martinez-Barros, Ramos Peek, Escobar-Izqulerdo, Figuera JR. Clinical, electrophysiologic and neuroimaging findings in Wernicke's syndrome. Clin Electroencephalogr. 1994;25:148–52. doi: 10.1177/155005949402500407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]