Abstract

We report an unusual occurrence of involuntary movement involving the tongue in a patient with confirmed Wilson's disease (WD). She manifested with slow, hypophonic speech and dysphagia of 4 months duration, associated with pseudobulbar affect, apathy, drooling and dystonia of upper extremities of 1 month duration. Our patient had an uncommon tongue movement which was arrhythmic. There was no feature to suggest tremor, chorea or dystonia. It might be described as athetoid as there was a writhing quality, but of lesser amplitude. Thus, the phenomenology was uncommon in clinical practice and the surface of the tongue was seen to “ripple” like a liquid surface agitated by an object or breeze. Isolated lingual dyskinesias are rare in WD. It is important to evaluate them for WD, a potentially treatable disorder.

Keywords: Dyskinesia, undulating tongue, Wilson's disease

Introduction

Wilson's disease (WD) is a disorder of copper metabolism. Following the first detailed description by Sir SAK Wilson's a century ago, it has been recognized that there is considerable heterogeneity in the clinical phenotype, imaging characteristics and genetic mutations. Movement disorders of the tongue, in isolation or in conjunction with affection of other body parts is rare, but has been reported in a wide spectrum of disorders. Lingual dyskinesias are rather uncommonly reported in WD.[1,2]

We present here an unusual movement disorder involving the tongue in a patient with confirmed WD.

Case Report

This was a case report of an 11-year-old girl, born to consanguineous parents with normal birth and developmental history presented with slow, hypophonic speech and dysphagia of 4 months duration, associated with pseudobulbar affect, apathy, drooling and dystonia of upper extremities of 1 month duration. Neurological examination revealed bilateral Kayser-Fleischer rings, slow, hypometric saccades, bilateral appendicular bradykinesia and slow tongue movements. In addition, the surface of the tongue in the resting state showed slow sinuous undulating movements that spread in a semi-rhythmic manner postero-anteriorly like a “ripple” [Video 1]. The movements disappeared on protrusion and side-to-side movement of the tongue. Rest of the neurological examination including motor, sensory and cerebellar systems was unremarkable. There was no history of jaundice in the patient; there was no history of neurological or hepatic disorder in the family.

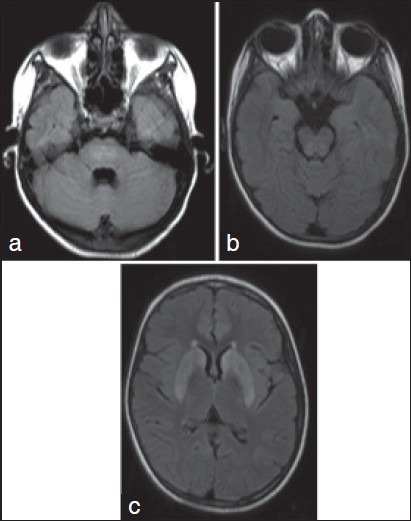

Investigations confirmed WD (serum ceruloplasmin: 7 mg/dl) (reference: 15-35 mg/dl); serum copper: 28 mcg/dl (reference: 75-160 mcg/dl); 24 h urinary copper: 349 mcg/24 h (reference: Up to 70 mcg/24 h). Abdominal ultrasound showed evidence of hepatic cirrhosis. Routine hemogram, liver and renal function tests were within the normal limits. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed hyperintense signals in bilateral caudate nuclei, putamina and thalami, central pons and dorsal mid-brain in the region of central tegmental tracts [Figure 1]. She received de-coppering therapy with d-penicillamine (250 mg/day) and zinc sulphate (660 mg/day). After 6 months, the lingual movements had improved significantly.

Figure 1.

Axial Fluid Attenuated Inversion Recovery (FLAIR) Magnetic Resonance Imaging of brain shows hyperintense signal changes in the center of the pons (a), dorsal mid-brain corresponding to the central tegmental tracts (b) and bilateral caudate nuclei and putamina (c)

Discussion

The dominant clinical manifestation is extrapyramidal and can be broadly grouped into Parkinsonian-type, ataxic or pseudosclerotic and tremor dominant forms. In one of the largest cohort of WD, the most common neurological manifestations included parkinsonism, dystonia, chorea, myoclonus and athetosis.[3] Other forms of dyskinesias including those involving the tongue in isolation are distinctly rare. This patient manifested with a unique lingual movement disorder that improved almost completely with de-coppering therapy.

Isolated or predominant lingual involvement in WD has been described albeit in isolated case reports. Lingual tremor has been described as the sole manifestation of WD in child. Liao et al. described a 15-year-old boy with lingual dyskinesias in the form of irregular contraction of the sides of the tongue as an early manifestation of WD.[1] Kumar and Moses reported involuntary protrusion of the tongue in an 11-year-old girl with WD.[2] Our patient manifested with an uncommon lingual movement; the movement was not rhythmic and oscillatory as would be expected in a tremor disorder. Neither did it have the irregular, continuous character of a chorea, or a sustained posturing as in the case of a dystonia. It could possibly be described as athetoid as there was a writhing quality, though the amplitude was not wide. Thus the phenomenology was unique and the surface of the tongue was seen to “ripple” like a liquid surface agitated by an object or breeze.

The pathophysiological substrate for this involuntary lingual movement is difficult to explain. Although most of the extrapyramidal manifestations of WD have been attributed to involvement of the basal ganglia,[3] the same cannot be extrapolated to explain the abnormal lingual movements as well. One can take a clue from other conditions wherein abnormal fasciculation, tremor, myoclonus, dyskinesias, undulating hyperkinesias and dystonia of the tongue have been described such as brainstem ischemia, head injury and chronic epilepsy.[4] It has been hypothesized that involvement of the pontine central tegmental tracts may play a role in the genesis of episodic lingual dyskinesias in patients with brainstem ischemia.[4] In patients with anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis, interruption of forebrain cortico-striatal inputs has been thought to remove the tonic inhibition of brainstem pattern generators releasing primitive patterns of bulbar and limb movement resulting in semirhythmic repetitive bulbar and limb movements.[4] Acute severe hemilingual dyskinesias have also been described in non-Wilson's, non-Menkes disorders of copper metabolism, in the presence of normal brain and spinal MRI, wherein it has been posited that abnormal copper deposition per se might cause abnormal lingual movements by yet unknown mechanism.[5]

Our patient had involvement of the fronto-striatal connections as evidenced by abnormal signals in the basal ganglia in brain MRI in addition to involvement of the pontine central tegmental tracts. Extrapolating the findings of previous authors, it is possible this structural abnormality coupled with an abnormal copper metabolism was responsible for the clinical phenomenology in our patient. Our patient improved with de-coppering therapy. Clinical improvement could be secondary to the resolution of structural brain abnormalities as well as reduction of copper toxicity.

Conclusion

The most common clinical manifestation in WD is related to the involvement of the cranio-facial musculature in the form of dystonia and pseudobulbar palsy resulting in slow tongue movements, dysarthria and dysphagia and drooling. Isolated lingual dyskinesias are distinctly rare; it is important to recognize and evaluate for WD as a part of the diagnostic work-up in such patients as this is a potentially treatable disorder. Nevertheless, the neurobiological basis of lingual dyskinesias remains to be elucidated.

See the Video on: www.annalsofian.org

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

References

- 1.Liao KK, Wang SJ, Kwan SY, Kong KW, Wu ZA. Tongue dyskinesia as an early manifestation of Wilson disease. Brain Dev. 1991;13:451–3. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(12)80048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar TS, Moses PD. Isolated tongue involvement – An unusual presentation of Wilson's disease. J Postgrad Med. 2005;51:337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taly AB, Meenakshi-Sundaram S, Sinha S, Swamy HS, Arunodaya GR. Wilson disease: Description of 282 patients evaluated over 3 decades. Medicine (Baltimore) 2007;86:112–21. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e318045a00e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee PH, Yeo SH. Isolated continuous rhythmic involuntary tongue movements following a pontine infarct. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2005;11:513–6. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goez HR, Jacob FD, Yager JY. Lingual dyskinesia and tics: A novel presentation of copper-metabolism disorder. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e505–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.