Abstract

The disparate responses of leukemia cells to chemotherapy in vivo, compared to in vitro, is partly related to the interactions of leukemic cells and the 3 dimensional (3D) bone marrow stromal microenvironment. We investigated the effects of chemotherapy agents on leukemic cell lines co-cultured with human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell (hu-BM-MSC) in 3D. Comparison was made to leukemic cells treated in suspension, or grown on a hu-BM-MSC monolayer (2D conditions). We demonstrated that leukemic cells cultured in 3D were more resistant to drug-induced apoptosis compared to cells cultured in 2D or in suspension. We also demonstrated significant differences in leukemic cell response to chemotherapy using different leukemic cell lines cultured in 3D. We suggest that the differential responses to chemotherapy in 3D may be related to the expression of N-cadherin in the co-culture system. This unique model provides an opportunity to study leukemic cell responses to chemotherapy in 3D.

Keywords: 3 dimensional, in vitro, leukemia, chemotherapy sensitivity

INTRODUCTION

Current in vitro drug testing models are based on 2-dimensional (2D) cell culture systems. Although widely used in pre-clinical testing, these models do not always predict in vivo responses.[1] These 2D culture systems do not reflect the true 3-dimensional (3D) microenvironment present in human tissues and/or tumors, whereby cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix (ECM) interactions occur. Such 3D microenvironment is considered fundamental to study cell proliferation, motility, and differentiation.[2],[3] This is especially true for a cancer like acute myeloid leukemia (AML), where responses predicted by current 2D cell culture models resulted in disappointing clinical outcomes.[4],[5],[6],[7] We hypothesize that a 3D cell culture model is more predictive of in vivo responses to anti-AML chemotherapy as it takes into account the ability of leukemia cells to interact with the bone marrow microenvironment as well as their ability to establish niches.[8] These niches offer partial protection from the effects of cytotoxic chemotherapy, also termed as cell adhesion-mediated drug resistance.[9] The ability of leukemia cells to establish self-protective niches in bone marrow is regulated by interactions between the stromal-secreted chemokine, stromal-derived factor 1α (SDF-1α), also known as CXCL12, and the receptor C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4).[10] This SDF-1a-CXCR4 interaction attracts the circulating leukemia cells to bone marrow niches [11] in the same way it is used for homing of hematopoietic cells.[12] Targeting the CXCL12-CXCR4 pathway, for example, provides a novel mechanism to disrupt the interaction between stroma-leukemia cells and disrupt the protective microenvironment of the leukemia cells using CXC4 antagonists.[13] The role of stromal protection of AML cells from toxic effects of chemotherapy is evident from previously published work.[14] McQueen et al. demonstrated that when AML blasts were co-cultured in vitro with human bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells (hu-BM-MSCs), MSCs protected leukemia cells from spontaneous apoptosis in all samples and from cytarabine chemotherapy cytotoxicity in six of eleven samples. The same authors also observed that the MSC-mediated resistance, regulated by the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway as a P13K/AKT inhibitor, was able to overcome the chemoresistance. Finally, bone marrow stromal cells have been implicated in stromal cell-mediated resistance to Fms-like tyrosine kinase-3 (FLT3) inhibition in FLT3 mutant AML.[15]

Recognizing the shortfalls of the 2D in vitro drug testing systems, several biomimetic 3D systems have been developed. For example, agarose or matrigel systems and spheroid cultures have improved our understanding of the role of 3D culture with cells, but these systems are unable to recreate distinct tumor niches.[16] More recently, 3D systems have been designed with synthetic scaffolds such as hydrogels [17] or poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLG)[16], which provide good structural support but again fail to mimic the interactions between cancer cells and stromal cells that occur in vivo. Taking into account the limitations with the reported 3D systems, we have developed and characterized an in vitro culture system that facilitates efficient interaction between leukemia cells with stromal cells in a 3D microenvironment, and hence, we believe this model will be more accurate in predicting in vivo responses to chemotherapy. In these experiments, we investigated the cytotoxic and apoptotic effects of cytotoxic chemotherapy on the HL-60,Kasumi-1, and MV411 cell lines cultured in an experimentally designed 3D cell culture model. In this 3D microenvironment, the HL-60 , Kasumi-1, and MV411 cells were co-cultured with expanded hu-BM-MSCs in a synthetic scaffold, polyglycolic acid/ poly L-lactic acid (PGA/PLLA) 90/10 copolymer scaffold. Previously this scaffold showed excellent seeding efficiencies and leukemic growth compared to other tested scaffolds.[18] Based on cell viability assays (MTT), 40% of HL-60 cells in traditional culture conditions can survive 10μM doxorubicin treatment.[19] In addition, studies have shown that cancer cells in traditional culture conditions can be several times more sensitive to chemotherapy compared to 3D culture conditions.[17],[20] Accordingly, we used high doses of doxorubicin to test the impact of doxorubicin on HL-60,Kasumi-1, and MV411 cells cultured in 3D conditions. Additionally, we measured the leukemic response to Cytosine β-D-arabinoside (cytarabine).

METHODS

Study Design

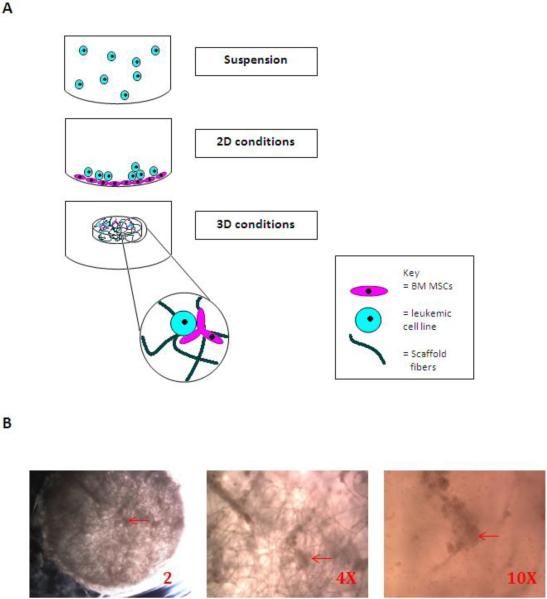

To study the apoptotic and cytotoxic response of leukemic cells in three culture conditions (figure-1A), leukemic cells were tested either cultured alone in suspension, grown over a monolayer of expanded hu-BM-MSCs (2D conditions), or co-cultured with expanded hu-BM-MSCs in a 3D scaffold (3D conditions)(figure-1B). Leukemic cells under these three culture conditions were exposed to several different doses of doxorubicin or cytarabine for either 24 or 48 hours. Apoptosis in leukemic cells was assessed by flow cytometry. Leukemic cell proliferative response to chemotherapy in 3D was verified by Ki-67 immunohistochemistry staining of 3D scaffold preserved sections. We also studied the proliferative response of the co-cultured leukemic cells and stromal cells in 3D and 2D using alamarBlue with some modifications.

Figure-1. Study culture conditions. A: A schematic presentation of the tested culture conditions.

In these experiments, leukemic cell lines are either cultured alone (suspension) or co-cultured over a human bone marrow mesenchyhmal stem cell (hu-BM-MSC) monolayer (2D conditions) or co-cultured with hu-BM-MSC in three dimensional construct (3D conditions). B: 3D scaffold containing hu-BM-MSCs (prior to seeding with leukemic cell lines and 14 days after hu-BM-MSCs seeding). Dense areas (red arrows) indicate attachment of MSCs to scaffold fibers. (2X, 4X, and 10X). The diameter of the scaffold is 5mm.

Diffusion Measurements

Image capture and analysis of fluorescent probe diffusion rates into seeded scaffolds was completed on a Fluoview scanning laser confocal microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA) fitted with a perfusion system (Bioscience Tools, San Diego, CA). To measure impeded diffusion rates, fluorescein-tagged dextran beads up to 1000 Da (Invitrogen, Life Technologies) were perfused into the chamber and images collected at a scan speed of 2 scans/sec. We chose a 1000 Da dextran, because it was significantly larger than the tested chemotherapeutic agents (doxorubicin hydrochloride = 579.98 Da and Cytosine β-D-arabinoside (cytarabine)= 243.22 Da. The rate of fluorescent bead entry into the seeded scaffolds was measured as the fluorescence signal in the outer layer of the scaffolds increased. The diffusion rate was calculated as the distance traveled by the leading fluorescent edge through the scaffold. The scanning rate was decreased after the first 10 minutes for subsequent measurements that were captured for up to 1 hour following the probe perfusion. Steady-state penetration of the probe was calculated after a minimum of 30 minutes incubation in the compound.

Chemotherapy adsorption assessment

To indirectly assess if chemotherapy drugs are adsorbed to scaffold fibers, we incubated empty scaffolds and seeded scaffolds with 20 µM of doxorubicin for 8 hours. Culture supernatants from empty scaffolds as well as from seeded scaffolds were then used separately to treat HL-60 cells in suspension. Cytotoxicity was assessed after 48 hour treatment using alamarBlue assay as detailed.

Cell Culture

Hu-BM-MSCs (STEMCELL Technologies Inc., BC, Canada) were cultured in MesenCult®-XF Basal Medium (STEMCELL Technologies Inc., BC, Canada) with MesenCult®-XF Supplement (STEMCELL Technologies Inc., BC, Canada) and 2mM L-glutamine in T-75 flasks coated with MesenCult®-XF attachment substrate as recommended by the supplier until third passage, when DMEM (Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium) (Fisher Scientific, IL) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) was used to replace the MesenCult®-XF complete medium for another passage. Medium was changed every other day. HL-60 cells (American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), Manassas, VA) were kindly provided by Joseph Fontes ( University of Kansas Medical Center) and maintained in Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium (RPMI) 1640 (Sigma) with 10% FBS (Sigma) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (pen/strep)(Life Technologies) . Kasumi-1 cell line (American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), Manassas, VA) was maintained in RPMI 1640 with 20%FBS and 1% pen/strep. The HL-60 cell line, represents a differentiated stage between the late myeloblasts and the promyelocyte[21], and Kasumi-1 cell line is originally derived from a patient with AML associated with 8;21 translocation.[22] MV411 cell line was kindly provided by Kathleen Sakamoto (Stanford School of Medicine) and was maintained in RPMI with 10% FBS, 1% pen/strep, and 2mm L-glutamine (Sigma). MV411 is a biphenotypic and monocytic leukemia cell line with 4;11 translocation and a FLT3/ internal tandem duplication (ITD) mutation.[23]

Seeding 3D Synthetic Scaffold with Expanded hu-BM-MSCs

Prior to seeding, polyglycolic acid/poly L-lactic acid (PGA/PLLA) 90/10 copolymer discs 5 mm in diameter and 2 mm in thickness (Synthecon Inc., Houston TX), were sterilized using 70% ethanol, then washed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) three times, and pre-treated with DMEM overnight. Human-BM-MSCs (5 ×105 cells/scaffold) were seeded into the scaffolds in 12-well non-tissue culture plates (2 scaffolds/well). The plates with the freshly seeded scaffolds were placed in an incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 30 minutes to 1 hour for attachment of stromal cells to the scaffold After 1 h, the medium was added to each well. The culture plate was then placed in an incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2 and maintained in DMEM with 10% FBS that was changed every other day for 14 days.

Seeding Density and Maintenance of HL-60 and Kasumi-1 in the Three Culture Conditions

HL-60 Cells,Kasumi-1 cells, or MV411 cells alone: 1×106/mL HL-60,Kasumi-1, or MV411 cells were cultured in each well of the 12-well tissue culture plates.

HL-60,Kasumi-1, or MV411 cells in 2D: 5×105/mL MSCs were seeded in each well of 12-well tissue culture plates until semi-confluence, then 1×106 /mL HL-60,Kasumi-1, or MV411 cells were added to each well and maintained for 3 days.

HL-60,Kasumi-1, or MV411 in 3D: After 14 days, the scaffolds containing MSCs were co-cultured with HL-60,Kasumi-1, or MV411cells (1×106 cells/mL) in 12 well plates. All cultures were done in triplicates. Cultures were maintained in RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS and 1% pen/strep in the case of HL-60 and in RPMI 1640 with 20% FBS and 1% pen/strep in the case of Kasumi-1 cell line in an incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. For MV411 RPMI with 10% FBS, 1% pen/strep, and 2mm L-glutamine was used.

Treatment with chemotherapy

Cells alone in suspension: After 1 day of culture, 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, or 50μM of doxorubicin hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis) or 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, or 2.0 μM of cytarabine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis) were used to treat HL-60 or Kasumi-1 cells for 24- or 48-hours. MV411 cells were treated with same doses of doxorubicin hydrochloride for 48-hours.

- 2D co-culture conditions: After 3 days of 2D co-culture, doxorubicin or cytarabine were used in the previously mentioned doses to treated HL-60 or Kasumi-1 cells for 24- or 48-hours. MV411 cells were treated with same doses of doxorubicin hydrochloride described previously for 48-hours.

3D co-culture conditions: For 3D conditions, HL60,Kasumi-1, or MV411 cells and MSCs were first co-cultured for 10 days. Then treatment with doxorubicin or cytarabine was given using the previously mentioned doses and treatment durations. MV411 cells were treated with same doxorubicin hydrochloride doses described previously for 48-hours. Just prior to treatment, the 3D scaffolds were transferred using sterile forceps to new 24-well plates and covered in fresh medium, then doxorubicin or cytarabine were added to achieve the final desired concentrations and plates were placed in an incubator for 24- or 48- hours. This step was included because MSCs tended to attach to the bottom of the culture wells which attracted leukemic cells to attach to stromal cells, creating 2D conditions within the same culture wells. Accordingly, to minimize the effects of these 2D conditions, the 3D scaffolds were transferred to new culture wells prior to treatment.

Supernatant pre-incubation and chemotherapy treatment: In this case, HL-60 cells were incubated with fresh medium and doxorubicin dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and suspended in collected supernatant in a 1:1 ratio.

Cytotoxicity assessment by alamarBlue assay

To assess the cytotoxic effect of chemotherapy drugs on leukemic cells, alamarBlue assay was used, with modifications. This in vitro fluorescent assay measures cell proliferation and cytotoxicity. Initially, leukemic cells where either cultured alone, under 2D, or 3D conditions in 24 well plates, and then each group was treated with cytotoxic chemotherapy. Four hours prior to proliferation assessment, 10% alamarBlue (Biocentric) was added into each well. After 4 hours, we transferred 100 μl of the supernatant of each well in 24 well plates to a new well of 96 well plate, followed by placing the 96 well plates into micro-plate reader to detect florescence with excitation wavelength at 530nm and emission wavelength at 590 nm.

Apoptosis Assessment by Flow Cytometry

HL-60 Cell Retrieval for Apoptosis Analysis

To retrieve HL-60 cells in 2D, the medium was first aspirated and added to a 15 ml conical tube. The adherent layer was washed with PBS once and the retrieved PBS was added to the 15 ml tube. Then MesenCult®-ACF Enzymatic Dissociation Solution (STEMCELL Technologies Inc., BC, Canada) and MesenCult®-ACF Enzyme Inhibition (STEMCELL Technologies Inc., BC, Canada) were added to retrieve the remaining attached cells. Incubation time was 2 min followed by aspiration of detached cells, which were added to the 15 ml tube. Finally, the wells were washed with PBS twice followed by gentle tapping of the plate, and the retrieved PBS was added to the 15 ml tubes. For HL-60 cells that remained attached, the dissociation solution step was repeated again until all cells were detached.

To retrieve HL-60 cells from 3D co-culture scaffolds, the scaffolds were removed with sterile forceps into a new 24-well plate with each scaffold placed in a single well. The scaffolds were washed with PBS twice, and the supernatant was transferred to a 15 ml conical tube. Subsequently, the scaffolds were cut into small pieces using a sterile scalpel, transferred to 50 ml conical tubes, and subjected to Non-enzymatic Cell Dissociation Solution 1X (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis) 1 ml/tube. After brief vortexing, the broken scaffold pieces were incubated for 20 min at 37°C followed by centrifugation at 300g for 10 min. The shredded pieces of scaffolds were washed with PBS again and the supernatant was added to a 15 ml tube. The release of cells from 3D scaffold was examined by microscopy.

Detection of Apoptosis by FITC-Annexin V-Flow Cytometry

HL-60 apoptotic response assessment was determined by flow cytometry using FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) following manufacturer's recommended procedures. At least 1 × 105 cells were used for each assessment. Prior to flow cytometry analysis, and to remove scaffold debris, the cell suspension was filtered through 35 μm nylon mesh incorporated into the tube cap (BD FACS™) System, which was used to collect the dissociated sample for downstream processing in flow cytometry. Since our 2D and 3D conditions have two cell populations, HL-60 and MSCs, we used allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated mouse monoclonal anti-human CD45 (R&D systems, Inc.) to label HL-60 cells and phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated mouse monoclonal anti-human CD105 (R&D systems, Inc.) to label hu-BM-MSCs in order to accurately measure apoptosis of only the leukemia cells.

Tissue Preparation for Histology Examination

To prepare 3D scaffold samples for histology examination, the scaffolds were transferred to a new 12-well plate, washed with PBS three times, and then transferred to plastic containers (2 scaffolds/ container). Optimal Cutting Temperature (OTC) (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA) was added to each container until the scaffolds became submersed. The samples were stored at −20°C until processing. Frozen sections, 5 micron in thickness, were used for histological analysis. Alternatively, scaffolds were submersed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained. Slides were reviewed using an Olympus BX40 microscope and pictures were taken using a DP72 digital camera. For 2D cultures, BM- MSC monolayers with attached leukemic cells generated from these experiments were scraped from the bottom of the culture wells and transferred to PreservCyt Solution® (Cytyc Corporation (Hologic), Marlborough, MA) and processed using Cellient Automated Cell Block System®. Eosin was applied and vacuum-drawn through the sample to visualize the cells. After isopropyl alcohol dehydration and xylene clearing, the samples were embedded in paraffin.

Histology Stains

For Ki-67 immunolocalization, slides containing frozen sections were air dried at room temperature for 30 minutes, fixed in an acetone/methanol/formaldehyde solution for 5 minutes, and rinsed with Tris-buffered saline. Antigen retrieval included a cirate pre-treatment step, incubating the slides in sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) in a Biocare Decloaking Chamber (Biocare Medical, Concord, CA) for 3 minutes under pressure 24 Ibs and at 120°C. The slides were washed with Tris buffer prior to peroxidase treatment. Following the quenching of endogenous peroxidase with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 minutes, the slides were incubated in a 1:400 dilution of Ki67, clone MIB-1, for 30 minutes (Dako USA, Carpinteria, CA). Detection was performed using the Dako Envision+ System-HRP (DAB) anti- mouse kit, per kit protocol, using the Dako Autostainer at room temperature per company protocol. The slides were lightly counterstained with Modified Harris Hematoxylin, dehydrated in progressive grades of alcohol, cleared with xylene and permanently mounted.

For N-cadherin immunohistochemical staining, anti-human N-Cadherin antibody (Code No. 18571, Immuno-Biological Laboratories, Minneapolis, MN ) was used. Epitope retrieval was performed in Biocare Decloaking Chamber (pressure cooker), under pressure for 5 min, using citrate pH 6.0 buffer. Endogenous peroxidases were blocked with 3% H2O2. The N-Cadherin primary antibody was used at 1:50 with a 60 minute incubation at room temperature, followed by Dako enVision+ anti-rabbit HRP detection for 30 minutes and Dako DAB+ for 5 minutes. A hematoxylin counterstain was used.

Ki-67 assessment

Automated Cellular Imaging System (ACIS) was used for Ki-67 assessment. ACIS uses advanced color detection software to identify and evaluate fixed and stained tissue on microscopic slides. The slides were scanned and a reconstructive image of the sample analyzed. The percent of positive Ki-67 cells in the sample based on color (brown) was detected. For each time point and condition in our experiments, at least three separate section samples were assessed and averaged.

Statistical Considerations

For alamarBlue data, the mean and standard deviation of fluorescence emission was calculated for each variable and normalized to controls. The means in each experiment were compared using one way analysis of variance (ANOVA). To compare the mean responses between two conditions (2D versus 3D, for example), we used two way ANOVA after normalization of the variables in each experiment to controls. Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test was used to compare mean fluorescence values in the chemotherapy adsorption study. The calculations were completed using Graphpad Prism software version 6 (GraphPad Software, Inc.)

Apoptotic response was measured according to the following categories: alive, early apoptosis, late apoptosis, or necrosis. Polychotomous logistic regression for a nominal response variable was used to determine the likelihood ratio test for treatment-by-culture condition interaction. SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., 2002-2008) was used for this statistical analysis

RESULTS

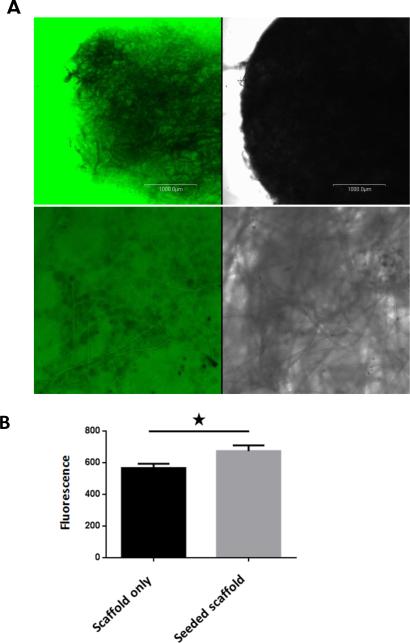

Seeded PGA/PLLA scaffold allows free diffusion of molecules up to 1000 Dalton

One of the major issues in designing a 3D model for chemotherapy testing is to make sure that the design allows media components and cytotoxic agents to freely diffuse to target cells. Any impedance to this process might impact cell survival or their response to chemotherapy treatment. Accordingly, we examined impeded diffusion in the seeded scaffolds measured by perfusing fluorescent dextrans into a perfusion chamber containing the scaffolds. Images were captured through the periphery and the core of the scaffold using confocal microscopy. Figure 1(left panels) illustrates that beads from 1000 Da had significant penetration into the seeded scaffolds. We confirmed this observation by analyzing the steady-state fluorescence of the separate cellular layers of the scaffold. The cell layers were identified in the transmitted light image, and used to analyze the identical fluorescence image (figure- 1-right panels). All Z-sections of the scaffolds were impregnated with the fluorescent dextran.

To indirectly assess chemotherapy adsorption to scaffold fibers, we incubated empty scaffolds and seeded scaffolds with chemotherapy for several hours and collected culture supernatants from both groups to separately treat HL-60 cells in suspension for 48 hours. If empty scaffold fibers were to adsorb chemotherapy more than seeded scaffolds, resulting in lower doses of drug in the supernatant, we would expect less proliferation of HL-60 cells cultured in chemotherapy supernatant from empty scaffolds. Indeed, there was a statistically significant difference, albeit slight, in fluorescence between the two groups with more fluorescence by alamarBlue assay evident in HL-60 cells cultured in supernatant collected from seeded scaffolds.

The collective proliferative response of 3D co-culture system indicates higher resistance to chemotherapy

In our co-culture conditions, leukemic cells as well as BM-MSCs grew together as a unit and the proliferative response to chemotherapy was compared in 2D vs. 3D cell culture systems. Cytotoxicity and proliferative assays for example ,alamarBlue, can be potentially utilized for this purpose as this assay does not distinguish which individual cell has contributed to the overall proliferative response under the tested condition. Accordingly, we used alamarBlue assay with some modifications to test the proliferative response of both the leukemic cells as well as the hu-BM-MSCs. This proliferative response is referred to as the collective proliferative response. We characterized the collective proliferative response in 3D co-culture conditions and compared it to 2D co-culture conditions as well as to leukemic cells treated in suspension.

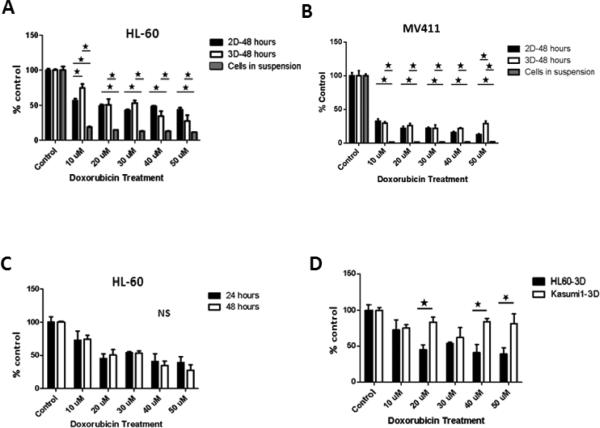

After 48-hours of doxorubicin treatment, there was a statistically significant decrease in the collective proliferative response of HL-60 and hu-BM-MSCs under 3D co-culture conditions (P<0.01) as well as 2D co-culture conditions (P<0.02) with increased doxorubicin doses (figure-3A). When compared to HL-60 cells treated in suspension, these collective proliferative responses were significantly higher in 3D as well as 2D (figure-3A). More importantly, there was a statistically significant difference in collective proliferative response between 3D and 2D co-culture conditions at 10 μM dose with higher collective proliferation in 3D compared to 2D (figure-3A). At higher doses, however, no statistically significant differences between 2D and 3D co-culture conditions were detected (figure-3A). Collectively, these results indicate that 2D and 3D co-culture conditions demonstrated less cytotoxicity to chemotherapy when compared to cell suspension conditions. Additionally, 3D co-culture conditions demonstrated less cytotoxicity to chemotherapy at lower doses, but not higher doses of chemotherapy.. Similar to HL-60 and after 48-hours of doxorubicin treatment, the collective proliferative responses of MV411 and BMMSCs significantly decreased with increased doxorubicin dose under both 2D and 3D culture conditions (figure-3B). However, there was a statistically significant difference in collective proliferative response between 3D and 2D co-culture conditions at 50 μM dose with higher collective proliferation in 3D compared to 2D (figure-3B).

Figure-3. Collective proliferative response to chemotherapy. A and B: 3D and 2D conditions in comparison to treated cells in suspension.

Forty eight-hours post treatment, HL-60 cells under both 3D and 2D culture conditions demonstrated significantly higher collective proliferative response compared to cells in suspension across all doses. The differences between 3D and 2D correlative proliferative response were not significantly different across doses except at the lowest dose of 10 μM dose, where 3D had significantly higher collective proliferative response (figure-2A). Similarly, the collective proliferative responses of MV411 and BM-MSCs were significantly higher in 3D as well as 2D compared to MV411 cells treated in suspension (figure-2B). However, there was a statistically significant difference in collective proliferative response between 3D and 2D co-culture conditions at 50 μM dose with higher collective proliferation in 3D compared to 2D (figure-3B). C: 3D collective proliferative responses according to duration of treatment. In C, the differences in the collective proliferative response of HL-60 cells cultured in 3D and treated for either 24 or 48 hours was not statistically significant. D: Differences between HL-60 and Kasumi-1 cells line responses when cultured in 3D. In D, Kasumi-1 cells in 3D demonstrate a significantly higher collective proliferative response in comparison to HL-60 in 3D in response to doxorubicin chemotherapy treatment. * Indicate statistical significance.

On the other hand, no significant differences between 2D and 3D culture conditions in terms of HL-60 or Kasumi-1 collective proliferative responses to cytarabine treatment for 24 hours (data not shown).

Duration of therapy did not impact the collective proliferative response to chemotherapy under 3D conditions

In these experiments, HL-60 cells co-cultured with hu-BM-MSCs in 3D and treated with several doses of doxorubicin for either 24- or 48-hours. We found no significant differences in the collective proliferative responses at 24 hours compared with 48 hours (figure-3C).

Collective proliferative response to chemotherapy between different leukemic cell lines in 3D is statistically significant

We investigated the collective proliferative response of a different leukemic cell line using our 3D model. We chose Kasumi-1, since Kasumi-1 cell line is biologically different from HL-60 cell line and we compared the collective proliferative responses of these two cell lines cultured in our model. Our goal was to determine if our 3D model could detect differences in the collective proliferative response that can be attributed to differences in the biological behaviors of the two cell lines. Indeed, a statistically significant increase in the collective proliferative response was noted in Kasumi-1, compared to HL-60, after 24-hour doxorubicin treatment (figure-3D). These results suggest that Kasumi-1 cells are more resistant to chemotherapy cytotoxic effects than HL-60 in our 3D model.

Determining the proliferative response of leukemic cells to chemotherapy treatment using Ki-67 IHC stain

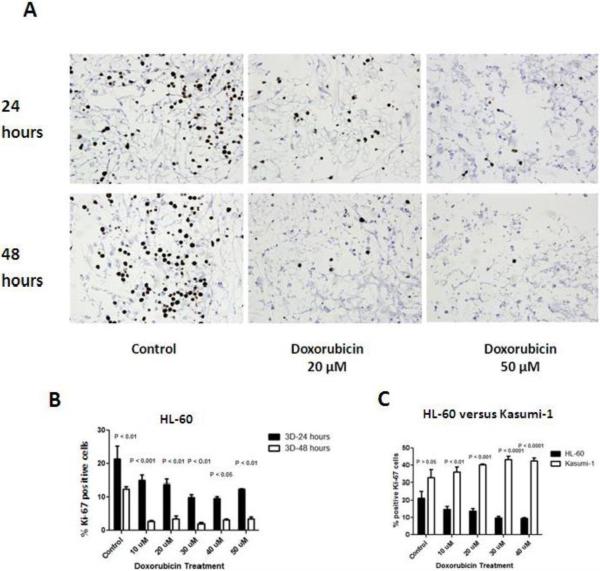

The previously described alamarBlue responses correlated with the collective proliferation of leukemic cells as well as BM-MSCs . To use another tool that could potentially correlate with alamarBlue responses but be more specific to leukemic cell proliferation in 3D co-cultures, we used Ki-67 assay. We determined Ki-67 responses in HL-60 and Kasumi-1 cells co-cultured with BM-MSCs in 3D conditions (figure-4).

Figure-4. Leukemic Cell Proliferation in response to doxorubicin treatment in the 3D Model measured by Ki-67.

A: a representable Ki-67 stained sections of 3D co-culture model where HL-60 cells and BMMSCs were co-cultured and treated with different doses of doxorubicin ( 0 (control), 20, and 50 and μM) for 24 or 48 hours. A decrease in the number of Ki-67 stained cells (brown cells) as the dose of treatment increased and as treatment duration increased. B: Bar graphs represent the percentage of Ki-67 positive cells in HL-60 cells cultured in 3D after doxorubicin treatment for both 24 hours and 48 hours. A significant decrease in the percentage of Ki-67 positive HL-60 cells was noted across doxorubicin doses. After 48 hours of treatment, a further and a significant drop in the percentage of Ki-67 positive was noted across all doses. C: Kasumi-1 cells demonstrated significantly higher percentage of Ki-67 expression across all doses and controls compared to HL-60 cells.

The proliferative response of leukemic cells to chemotherapy in 3D conditions decreases in a dose and time dependent manner

In these experiments we investigated the effects of chemotherapy doxorubicin on HL-60 cell line co-cultured in our 3D model and treated with various doses of doxorubicin chemotherapy for 24 or 48 hours. We demonstrated a statistically significant dose dependent decrease in the percentage of Ki-67 staining HL-60 cells treated for 24 hours. However, 48 hour treatment did not lead to significant differences across the various chemotherapy doses (figure-4A and B). In terms of the impact of treatment duration, after 48 hours of treatment a significant drop in the percentage of Ki-67 positive was noted across all doses (figure-4B).

The proliferative response to chemotherapy in 3D conditions is cell-line specific

In earlier results, we have shown that the correlative proliferative response of leukemic cells cultured in 3D was significantly different with Kasumi-1 cells being more resistant to chemotherapy effects. In these experiments we determined the Kasumi-1 cell responses and compared it to HL-60 cells responses under similar doses and treatment duration conditions. We hypothesized that Kasumi-1 cells will have higher proliferative response across the various chemotherapy doses. Indeed, Kasumi-1 cells demonstrated significantly higher percentage of Ki-67 expression across all doxorubicin treatment doses and even control in comparison to HL-60 cells (figure-4C).

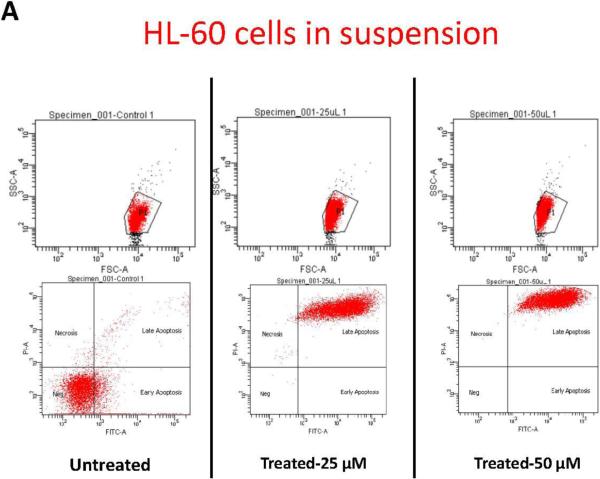

HL-60 cell co-cultured in 3D are more resistant to drug-induced apoptosis in comparison to HL-6o cells cultured alone or co-cultured in 2D

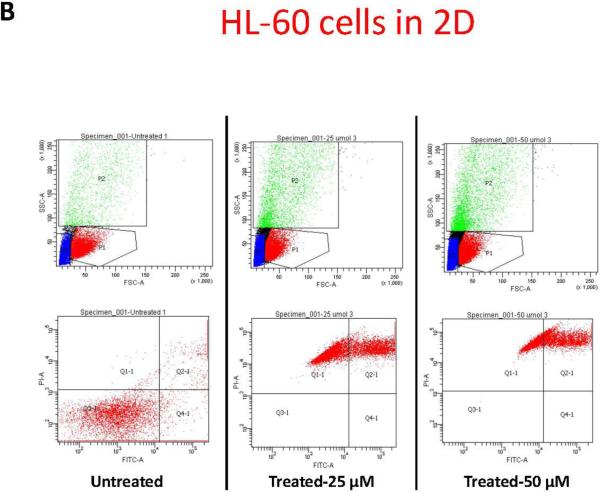

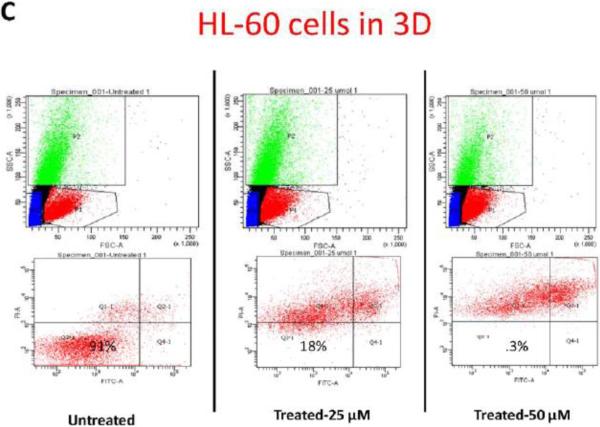

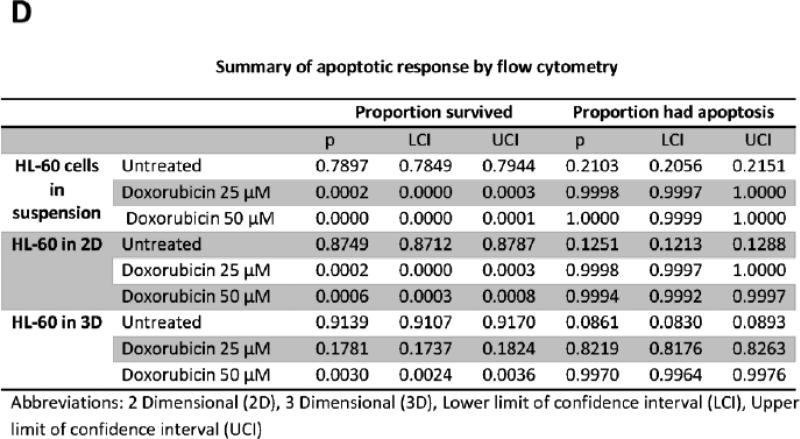

To further study the impact of leukemic cell culture condition on leukemic cell responses to chemotherapy, we developed a methodology that allowed the extraction of the cellular components of the model. Secondary antibodies to the different cell lines were used to gate the population of interest. HL-60 cells, accordingly, were identified according to CD45 expression. Using flow cytometry we determined the percentage of CD45 cells undergoing apoptosis. This methodology allowed us to quantitatively determine the degree of apoptosis in HL-60 cells according to the culture conditions, either alone in suspension, in 2D, or in 3D (figure-5). In accordance with prior data, flow cytometry gated on CD45 positive cells showed that more than 99% of HL-60 cultured alone, or co-cultured with MSCs in 2D conditions underwent apoptosis when treated for 24-hours with either 25, or 50 μM concentrations of doxorubicin. In 3D conditions, on average 82% of HL-60 co-cultured with MSCs underwent apoptosis with 25 μM of doxorubicin . 50 μM dose of doxorubicin induced apoptosis in 99.7% ofHL-60 cells in 3D (figure-5). These differences in apoptosis response in 3D compared to the other culture conditions were considered statistically significant (P<0.001).

Figure-5. Apoptosis flow cytometry using FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit.

A: Apoptotic response in HL-60 cells in suspension. B: Apoptotic response in HL-60 cells in 2D cell culture system. C: Apoptotic response in HL-60 cells in 3D cell culture system. The differences in apoptosis ratios between the three groups was statistically significant (P<.0001). P1 indicates CD 45 positive population, which was used to differentiate HL-60 cells from MSCs and was used to gate on the HL-60 cells for apoptosis. D: table-1 summary of the HL-60 apoptotic response in the three culture conditions.

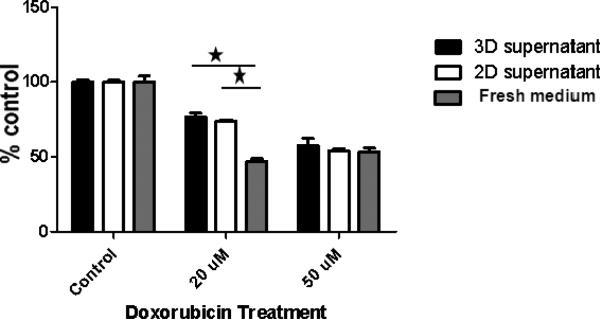

Soluble factors in 2D and 3D culture conditions comparably protected leukemic cells against lower doses of chemotherapy

The 3D culture conditions in our model can impact leukemic cell responses to chemotherapy in two ways. In one way, the stromal cells could be producing soluble factors that protect the leukemic cells against chemotherapy effects. Additionally, the leukemic cell adhesion to stroma might be providing the leukemic cells with a protective niche. To examine the first possibility related to soluble factors produced by stroma, we collected supernatant from 2D (following 3 day of culture) and 3D (following one week of culture) Hu-BM-MSC cultures and pre-incubated HL-60 cells with the collected supernatant prior to chemotherapy treatment. We pre-incubated HL-60 cells with supernatant and fresh media in a 1:1 ration and treated with doxorubicin (20 and 50 μM) for 24 hours. For control, we pre-incubated HL-60s with fresh media only. No significant differences were detected in HL-60 cell proliferative responses when pre-incubated in either 2D or 3D supernatant and treated with similar doses of doxorubicin. However, pre-incubation with 2D or 3D supernatant resulted in a significantly higher HL-60 proliferative response at 20 μM in comparison to control. At 50 μM these differences were abolished (figure-6). Collectively, these data suggest that soluble factors in 2D and 3D culture condition protect leukemic cells against chemotherapy cytotoxic effects and that the protection offered by these soluble factors in 2D and 3D culture conditions is very comparable. However, this protective effect is abolished when leukemic cells encounter much higher doses of chemotherapy.

Figure-6. Impact of pre-incubating HL-60 cells with 3D versus 2D supernatants on HL-60 proliferative response.

HL-60 cells were pre-incubated with BM-MSC supernatants obtained separately from 2D and 3D culture conditions and mixed with fresh media in a 1:1 ration. For control, HL-60 cells were pre-incubated with fresh media. HL-60 cells pre-incubated with 3D supernatant, 2D supernatant and fresh media (control) were then treated with doxorubicin (20 and 50 μM doses) for 24 hours. There were no significant differences in HL-60 cell proliferative response when pre- incubated in either 2D or 3D supernatants. However, HL-60 pre-incubated with either 2D or 3D supernatants demonstrated significantly higher proliferative response doxorubicin 20 μM compared to control. At the higher doxorubicin dose of 50 μM dose these differences were abolished.

N-cadherin expression, a potential mechanism for chemotherapy resistance in our 3D co-culture model

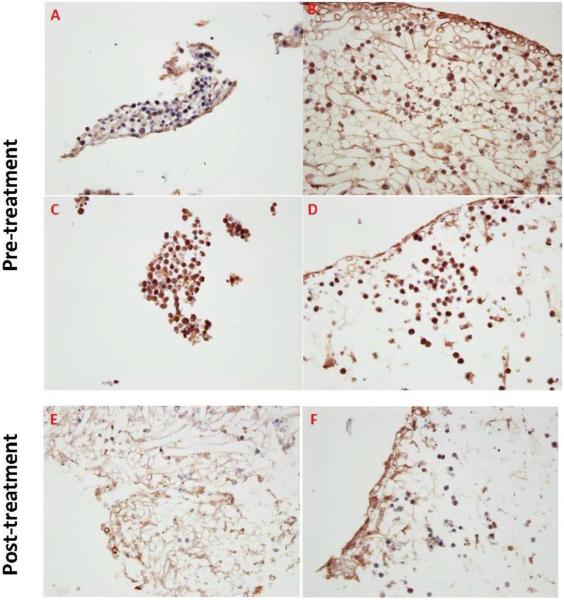

The data presented thus far demonstrate that 3D co-culture conditions protected leukemic cells against chemotherapy effects. We also demonstrated that soluble factors produced in either 3D or 2D co-culture conditions did not explain the differences in HL-60 apoptotic and proliferative responses to doxorubicin chemotherapy treatment under 2D and 3D conditions. These findings point to a contact-mediated mechanism for chemotherapy resistance in our model. Accordingly, we explored another potential mechanism for chemoresistance related to adhesion of leukemic cells to stromal elements which is N-cadherin expression. Using IHC, we observed that HL-60 cells demonstrated less N-cadherin expression in 2D compared to 3D culture conditions (figure-7), suggesting that N-cadherin expression and its related cell adhesion play a role in regulating chemotherapy resistance seen in our 3D model. On the other hand, Kasumi-1 cells demonstrated no significant differences in N-cadherin expression in 2D and 3D conditions. This differential expression of N-cadherin by IHCmight potentiallyexplain the differences in proliferative response to doxorubicin between Kasumi-1 and HL-60 cells cultured in 3D. Further, N-cadherin expression by IHC was lower in HL-60 cells following 48 hours of 50 μM doxorubicin treatment, but, to a lesser extent in Kasumi-1 cells following 24 hours of 50 μM doxorubicin treatment (figure-6E and F).

Figure-7. N-cadherin expression, a potential mechanism for chemotherapy resistance in our 3D culture conditions.

A: HL-60 2D, B: HL-60 3D, C: Kasumi-1 2D, D: Kasumi-1 3D, E: HL-60 3D 48 hours following doxorubicin 50 μM treatment, and F: Kasumi-1 3D 24 hours following doxorubicin 50 μM treatment. HL-60 cells did not express N-cadherin in 2D as strongly as in 3D. On the other hand, Kasumi-1 cells strongly expressed N-cadherin in both 2D and 3D culture conditions. Interestingly, the stromal elements were more apparent in the case of co-culture with HL-60(A and B) and less in Kasumi-1 (D and E). Post-therapy, most HL-60 cells and to lesser extent Kasumi-1 cells lost N-cadherin expression.

DISCUSSION

The results described here demonstrated the importance of co-culturing leukemic cell lines and hu-BM-MSCs that not only provides a 3D the mechanical structure, but also provides hu-BM-MSC niches that allowed leukemic cells to survive and proliferate, potentially protecting them against chemotherapy effects. Within our 3D co-culture system, we were able to assess leukemic cell responses to chemotherapy in 3D culture conditions and the collective proliferative response of leukemic cells and hu-BM-MSCs to chemotherapy, demonstrating the potential utility of this 3D model system in the pre-clinical setting.

One of the critical features of a 3D model is to allow cultured leukemic cells to proliferate. In our experiments, we demonstrated that HL-60 and Kasumi-1 cells co-cultured with hu-BM-MSCs in 3D proliferated even when exposed to chemotherapy. Earlier literature suggested that exposure of leukemic cells to cyclophosphamide chemotherapy resulted in initial increased incorporation of tritiated thymidine (TdR-3H) into treated cells, consistent with their proliferation, followed by decreased uptake consistent with an inhibitory effect.[24],[25] In these earlier reports, this effect was found to be time dependent and attributed to human serum factors.[24]However, these differences were not detected in our 3D model when the collective proliferative response of HL-60 and hu-BM-MSCs was measured by alamrBlue. This is likely because most cells that survived were hu-BM-MSCs. Indeed, when Ki-67 responses in leukemic cells were checked, a significant drop in HL-60 proliferative response was detected after a 48 hour treatment in 3D conditions.

Assessment of collective proliferative response to chemotherapy is a concept that we suggest should be further explored. In clinical setting, treating leukemia means treating leukemic cells within their niches, including their stromal niche, and not individual leukemic cells suspension. Accordingly, if the treatment succeeds in causing leukemia cell toxicity in the majority of cells, but few continue to survive within a stroma that is resistant to chemotherapy effects, persistence of these residual leukemia cells may ultimately result in disease relapse. Our model provides an opportunity to study this collective response using alamarBlue assay, while allowing a more detailed look at leukemic cell responses by flow cytometry or by assessing Ki-67 responses.

Our 3D model helped demonstrate significant differences in leukemic cell biological responses to treatment. For example, HL-60 cells cultured in 3D and in comparison to 2D, were more proliferative in response to doxorubicin 10 μM. Also, Kasumi-1 cells demonstrated higher proliferative response compared to HL-60 at higher doses of doxorubicin. Interestingly, MV411 cultured in 3D demonstrated a similar proliferative response to chemotherapy when cultured in 2D except at the highest dose of doxorubicin 50μM. These differences are likely attributed to differences in biological behavior of different leukemia cell lines[26], and underscore the heterogeneity of disease in both in vitro models and clinical AML. Our model provided a potential explanation for some of these observations. To explain, our preliminary findings point to differences in N-cadherin intensity expression by IHC in 3D compared to 2D culture conditions in the case of HL-60 cells. We found that N-cadherin expression was more intense in HL-60 cells co-cultured in 3D in comparison to 2D. This might explain why HL-60 cells in 3D demonstrated a higher proliferative response than in 2D when treated with doxorubicin at 10 μM. Also, we demonstrated that Kasumi-1 cells strongly expressed N-cadherin even in 2D co-culture conditions while HL-60 cells only expressed N-cadherin in 3D. We hypothesize that this increased expression of N-cadherin in Kasumi-1 cells might be why these cells demonstrated a higher proliferative response to doxorubicin treatment in comparison to HL-60 cells.

Our model provides an opportunity to study the role of N-cadherin in stroma-mediated drug resistance. This role of N-cadherin in mediating leukemic cell resistance is largely unknown. Recent literature suggests that N-cadherin might be even a marker of leukemic stem cells.[27] In this study, N-cadherin was found to be enriched in leukemic cells that express the leukemic stem cell phenotype CD34(+)/CD38(−)/CD123(+) following chemotherapy treatment. Besides this potential role for N-cadherin as a leukemic stem cell marker, N-cadherin has been recognized as an important component of the hematopoietic stem cell niche and its regulation.[28], [29], [30]

The ability of MSCs to establish hematopoietic niches was elegantly explored by Sacchetti et al.[31] In these experiments, isolated hu-BM-MSCs were able to establish heterotopic bone marrow when transplanted in a xenograft mouse model. Similarly, Vaiselbuh et al. used hu-BM-MSCs to seed a 3D scaffold, which created an ectopic leukemic niche in a NOD/SCID mice model.[32] This ectopic hematopoietic niche was made of adipocytes, blood vessels, and osteoclasts differentiated from the seeded MSCs. In contrary to these models, our model is stromal based and is an in vitro model. In our model leukemic cells were able to lodge in stromal niches and proliferate without differentiating to other niche components. Additionally, in our experiments, we did not use the chemokine stromal derived factor-1 (SDF-1) to help attract the leukemic cells to these niches; however, we theorize that N-cadherin expression by the MSCs attached to scaffolds is what attracted leukemic cells to the niches in our 3D model. In future experiments, we plan to optimize our co-culture conditions in preparation of chemotherapy treatment and optimize timing of treatment.

Our study adds to the body of evidence highlighting the shortfalls of current cell-based culture conditions and even 2D co-culture conditions. It points to differences in leukemic cell responses to chemotherapy when cultured alone or co-cultured with stromal cells 2D conditions compared to 3D co-culture conditions. It also demonstrates the ability of a significant population of leukemic cells, in the case of HL-60 cells, cultured in 3D to resist doses of doxorubicin high enough to cause apoptosis in cells cultured alone or in 2D. However, this response in 3D remained dose-dependent. In theory, this resistant leukemic cell population is likely what constitutes the minimal residual disease population that results in leukemia relapse following apparent successful remission induction therapy. This model provides an opportunity to study this population in more detail. Some might argue that these effects are artificial and related to the 3D design, which might prevent significant chemotherapy penetration and equivalent chemotherapy distribution to HL-60 cells in different parts of the 3D model. However, the diffusion tests we conducted argue against that and suggest that the molecules up to 1000 Da freely diffused throughout the model. Additionally, the impact of therapy on N-cadherin expression and Ki-67 expression across different doses and treatment duration support a potential effect on leukemic cells in the 3D model. Chemotherapy adsorption to scaffold fibers was indirectly assessed by incubating empty scaffolds and seeded ones with chemotherapy that were used to treat fresh HL-60 cells. We did notice small differences in HL-60 responses to chemotherapy supernatants from empty scaffolds and seeded ones. Though chemotherapy adsorption to scaffold fibers might explain these findings, the small difference between the two groups could be potentially explained by the secretion of protective and soluble factors by MSCs that could have resulted in more proliferation in HL-60 cells cultured in supernatant collected from seeded scaffolds. Also, comparable collective proliferative responses to chemotherapy between 2D and 3D culture conditions were noticed across several chemotherapy doses, suggesting that these adsorption effects in 3D are negligible.

Ultimately, our goal is to develop an in vitro model that can be used to predict in vivo responses to chemotherapy. Our model is a candidate model to be used in this capacity, and our data provide evidence that this model warrants further study. Our model has several potential applications in the pre-clinical testing of novel therapies as well as in the understanding of leukemia biology. For example, it can be used as an in vitro tool to choose between different chemotherapy agents based on drug sensitivity in patients who do not respond to therapy or those who are resistant to first line therapy. In addition, it provides an in vitro tool to isolate and characterize resistant leukemia sub-populations. Although using AML animal models for in vivo chemotherapy testing is a logical and necessary step prior to human testing, it is time-consuming and expensive with mixed clinical results. A model such as this will lead to biologically relevant pre-clinical models taking into consideration the dynamic interactions between leukemia cells and the bone marrow microenvironment. Improvements in in vitro testing methods will allow for more efficient screening, ultimately leading to the selection of a smaller number of candidate chemotherapy agents with increased potential for efficacy for in vivo testing.

In conclusion, our efforts represent early attempts to optimize AML 3D culture conditions to test chemotherapy responses in vitro. These efforts reflect a further progress in our ability to understand leukemia cell behavior and the interaction between leukemic cells and stromal elements in vivo. It also underscores the importance of the leukemia cell microenvironment and the role it plays in protecting resistant leukemia cells. This 3D microenvironment should be a target for future research directed at improving leukemia therapy.

Figure-2. Chemotherapy distribution in 3D model. A: Free diffusion of fluorescein-tagged dextran beads up to 1000 Da in PGA/PLLA scafolding material already seeded with mesenchmal stem cells and cultured for 2 weeks.

In these conofocal microscorpy pictures, the fluorescein-tagged dextran beads freely diffused throughout the seeded PGA/PLLA scafolding material. In upper panel, a picture of the seeded scaffold was taken 44 min (A&B). In lower panel, the picture was taken 60 minutes after adding the dextran beads and it represents a higher magnification of the center of the scaffold (C&D). B&D represent transmitted light images and A&C represent identical fluorescence images of B&D, respectively. Scale bar represents 1000 μm. B: Chemotherapy adsorption to 3D model fibers. To assess the impact of chemotherapy adsorption to scaffold fibers, empty scaffolds and seeded ones were incubated with 20 μM of doxorubicin for 8 hours. Culture supernatants from empty scaffolds and from seeded ones were then used separately to treat HL-60 cells in suspension. Cytotoxicity was assessed after 48 hour treatment by alamarBlue assay. The bar graph represents the mean +/− standard deviation values for fluorescence of the two groups. In these experiments there was a statistically significant difference in fluorescence between the two groups with more fluorescence evident in HL-60 cultured in supernatant collected from seeded scaffolds. * Indicate statistical significance

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an American Cancer Society-Institutional l Research Grant (IRG-09-062-01). We thank Marsha Danley, who processed the histology specimens and Richard Hastings for his technical help with flow cytometry experiments. O.S.A is a recipient of a research career award by the Office of Scholarly, Academic & Research Mentoring (OSARM) at his home institution, the University of Kansas Medical Center. We thank Bruce Kimler who critically reviewed the manuscript and Anna Ludlow for her help in preparing the tables and bar graphs. Finally, we thank Linheng Li, PhD for his advice regarding N-cadherin mediated leukemic cell and stroma interactions.

References

- 1.Kunz-Schughart LA, Freyer JP, Hofstaedter F, Ebner R. The use of 3-D cultures for high-throughput screening: the multicellular spheroid model. J Biomol Screen. 2004;9:273–285. doi: 10.1177/1087057104265040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cukierman E, Pankov R, Stevens DR, Yamada KM. Taking cell-matrix adhesions to the third dimension. Science. 2001;294:1708–1712. doi: 10.1126/science.1064829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lukashev ME, Werb Z. ECM signalling: orchestrating cell behaviour and misbehaviour. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:437–441. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(98)01362-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delmer A, Marie JP, Thevenin D, Suberville AM, Zittoun R. Treatment of relapsing and refractory adult acute myeloid leukemia according to in vitro clonogenic leukemic cell drug sensitivity. Leuk Lymphoma. 1993;10:67–71. doi: 10.3109/10428199309147358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khoury HJ, Garcia-Manero G, Borthakur G, et al. A phase 1 dose-escalation study of ARRY-520, a kinesin spindle protein inhibitor, in patients with advanced myeloid leukemias. Cancer. 2011 doi: 10.1002/cncr.26664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wacheck V, Lahn M, Dickinson G, et al. Dose study of the multikinase inhibitor, LY2457546, in patients with relapsed acute myeloid leukemia to assess safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics. Cancer Manag Res. 2011;3:157–175. doi: 10.2147/CMR.S19341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lapusan S, Vidriales MB, Thomas X, et al. Phase I studies of AVE9633, an anti-CD33 antibody-maytansinoid conjugate, in adult patients with relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Invest New Drugs. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10637-011-9670-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colmone A, Amorim M, Pontier AL, Wang S, Jablonski E, Sipkins DA. Leukemic cells create bone marrow niches that disrupt the behavior of normal hematopoietic progenitor cells. Science. 2008;322:1861–1865. doi: 10.1126/science.1164390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li ZW, Dalton WS. Tumor microenvironment and drug resistance in hematologic malignancies. Blood Rev. 2006;20:333–342. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin SJ, Kuo ML. Cytotoxic function of umbilical cord blood natural killer cells: relevance to adoptive immunotherapy. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;28:640–646. doi: 10.3109/08880018.2011.613092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sipkins DA, Wei X, Wu JW, et al. In vivo imaging of specialized bone marrow endothelial microdomains for tumour engraftment. Nature. 2005;435:969–973. doi: 10.1038/nature03703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oran B, Wagner JE, DeFor TE, Weisdorf DJ, Brunstein CG. Effect of conditioning regimen intensity on acute myeloid leukemia outcomes after umbilical cord blood transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17:1327–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burger JA, Peled A. CXCR4 antagonists: targeting the microenvironment in leukemia and other cancers. Leukemia. 2009;23:43–52. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teresa McQueen MK, Andreeff Michael. Activity of Targeted Molecular Therapeutics Against Primary AML Cells: Putative Role of the Bone Marrow Microenvironment. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts) 2005;106:2304. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kojima K, McQueen T, Chen Y, et al. p53 activation of mesenchymal stromal cells partially abrogates microenvironment-mediated resistance to FLT3 inhibition in AML through HIF-1{alpha}-mediated down-regulation of CXCL12. Blood. 2011;118:4431–4439. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-334136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fischbach C, Chen R, Matsumoto T, et al. Engineering tumors with 3D scaffolds. Nat Methods. 2007;4:855–860. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dainiak MB, Savina IN, Musolino I, Kumar A, Mattiasson B, Galaev IY. Biomimetic macroporous hydrogel scaffolds in a high-throughput screening format for cell-based assays. Biotechnol Prog. 2008;24:1373–1383. doi: 10.1002/btpr.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blanco TM, Mantalaris A, Bismarck A, Panoskaltsis N. The development of a three-dimensional scaffold for ex vivo biomimicry of human acute myeloid leukaemia. Biomaterials. 2010;31:2243–2251. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.11.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colado E, Alvarez-Fernandez S, Maiso P, et al. The effect of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib on acute myeloid leukemia cells and drug resistance associated with the CD34+ immature phenotype. Haematologica. 2008;93:57–66. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nirmalanandhan VS, Duren A, Hendricks P, Vielhauer G, Sittampalam GS. Activity of anticancer agents in a three-dimensional cell culture model. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2010;8:581–590. doi: 10.1089/adt.2010.0276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drexler HG, Quentmeier H, MacLeod RA, Uphoff CC, Hu ZB. Leukemia cell lines: in vitro models for the study of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Leuk Res. 1995;19:681–691. doi: 10.1016/0145-2126(95)00036-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asou H, Tashiro S, Hamamoto K, Otsuji A, Kita K, Kamada N. Establishment of a human acute myeloid leukemia cell line (Kasumi-1) with 8;21 chromosome translocation. Blood. 1991;77:2031–2036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zheng R, Bailey E, Nguyen B, et al. Further Activation of FLT3 Mutants by FLT3 Ligand. Oncogene. 2011;30:4004–4014. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burke PJ, Diggs CH, Owens AH., Jr. Factors in human serum affecting the proliferation of normal and leukemic cells. Cancer Res. 1973;33:800–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karp JE, Burke PJ. Influence of humoral regulators on proliferation and maturation of normal and leukemic cells. Cancer Res. 1976;36:1674–1679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hozumi M. Established leukemia cell lines: their role in the understanding and control of leukemia proliferation. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 1985;3:235–277. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(85)80028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhi L, Wang M, Rao Q, Yu F, Mi Y, Wang J. Enrichment of N-Cadherin and Tie2-bearing CD34+/CD38-/CD123+ leukemic stem cells by chemotherapy-resistance. Cancer Lett. 2010;296:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang J, Niu C, Ye L, et al. Identification of the haematopoietic stem cell niche and control of the niche size. Nature. 2003;425:836–841. doi: 10.1038/nature02041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haug JS, He XC, Grindley JC, et al. N-cadherin expression level distinguishes reserved versus primed states of hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:367–379. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hosokawa K, Arai F, Yoshihara H, et al. Cadherin-based adhesion is a potential target for niche manipulation to protect hematopoietic stem cells in adult bone marrow. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:194–198. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sacchetti B, Funari A, Michienzi S, et al. Self-renewing osteoprogenitors in bone marrow sinusoids can organize a hematopoietic microenvironment. Cell. 2007;131:324–336. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vaiselbuh SR, Edelman M, Lipton JM, Liu JM. Ectopic human mesenchymal stem cell-coated scaffolds in NOD/SCID mice: an in vivo model of the leukemia niche. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2010;16:1523–1531. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2010.0179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]