Abstract

It is commonly assumed that early emotional signals provide relevant information for social cognition tasks. The goal of this study was to test the association between (a) cortical markers of face emotional processing and (b) social-cognitive measures, and also to build a model which can predict this association (a and b) in healthy volunteers as well as in different groups of psychiatric patients. Thus, we investigated the early cortical processing of emotional stimuli (N170, using a face and word valence task) and their relationship with the social-cognitive profiles (SCPs, indexed by measures of theory of mind, fluid intelligence, speed processing and executive functions). Group comparisons and individual differences were assessed among schizophrenia (SCZ) patients and their relatives, individuals with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), individuals with euthymic bipolar disorder (BD) and healthy participants (educational level, handedness, age and gender matched). Our results provide evidence of emotional N170 impairments in the affected groups (SCZ and relatives, ADHD and BD) as well as subtle group differences. Importantly, cortical processing of emotional stimuli predicted the SCP, as evidenced by a structural equation model analysis. This is the first study to report an association model of brain markers of emotional processing and SCP.

Keywords: N170, SEM, social cognition, ADHD, BD, schizophrenia

INTRODUCTION

In everyday social cognition contexts, facial and semantic emotional information seems to provide shortcuts for understanding, acting and predicting social outcomes (Adolphs, 2003; Adolphs and Skuse, 2006; Barrett et al., 2007; Adolphs, 2009, 2010; Ibanez and Manes, 2012). However, the commonly accepted assumption that emotional signals involve an early processing associated with social cognitive skills has rarely been investigated at the empirical level. Although no direct evidence of an association among neural markers of emotional processing and social cognition performance has been provided, a few studies have assessed the degree to which face perception is associated with other domains, such as face memory (Herzmann et al., 2010; Wilhelm et al., 2010). People who are skilled in facial and semantic emotional processing should also be skilled in social cognition tasks. If this is true, then people who are suffering from neuropsychiatric conditions involving emotional processing impairments, such as schizophrenia (SCZ), bipolar disorder (BD) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), should also have impaired social cognition abilities. In this study, we propose that early cortical markers of emotional modulation would be associated with the social-cognitive profiles (SCPs) in healthy participants as well as in these different psychiatric conditions.

The study of the neural basis of emotional processing and face recognition is an exceptionally active research field [see reviews Itier and Batty (2009), Atkinson and Adolphs (2011), Calder et al. (2011), Sabatinelli et al. (2011), Said et al. (2011)]. The N170 is an early event-related potential (ERP) sensitive to face stimuli (Botzel et al., 1995; Bentin et al., 1996), and it is currently the most widely used measure of face processing (Rossion and Gauthier, 2002; Rossion and Jacques, 2008). Specifically, the N170 is a face cortical correlate with main neural generators in the fusiform gyrus and the superior temporal sulcus (STS) (Deffke et al., 2007; Sadeh et al., 2008). The N170 signal is primarily modulated by stimulus type (ST) discrimination (object recognition) between faces and objects/words (Rossion et al., 2003). In addition, the N170 can be modulated by emotional processing (Ashley et al., 2004; Righart and de Gelder, 2008a,b; Ibanez et al., 2010, 2011a). Thus, this component is an adequate brain marker of facial and emotional processing. Recently, a dual valence task (DVT) (Ibanez et al., 2011a,b, 2012a,b), in which faces and words are presented to test the effects of the ST (faces, words or face–word stimuli) and valence (positive vs negative stimuli) has provided evidence of the right N170 amplitude modulation by emotional (positive > negative) and ST effects (face > words).

In this study, we tested the association between the N170 and social-cognitive measures, and propose a model of this association that could accommodate the data from healthy volunteers and various groups of patients. We evaluated the accuracy of this model in participants with individual differences in emotional processing and facial/semantic processing, such as healthy volunteers, SCZ patients and their first-degree relatives, individuals with BD and with ADHD.

The intertwining of emotional processing, social cognition and cognitive processing in neuropsychiatric disorders

Biomarkers of emotional processing have a high clinical relevance for several adult neuropsychiatric disorders, such as SCZ (de Achaval et al., 2010; Goghari et al., 2011; Taylor and Macdonald, 2011), ADHD (Marsh and Williams, 2006) and BD (Kohler et al., 2011). These conditions share some symptomatology, are often co-morbid, and result in emotional processing impairments. In addition, individual differences in emotional processing are observed in these conditions. However, only a few studies have compared emotional processing in ADHD and BD (Brotman et al., 2010; Passarotti et al., 2010a,b), or in BD and SCZ (Addington and Addington, 1998; Besnier et al., 2011). Similarly, the response to emotional facial expressions might be a potentially useful biomarker for both ADHD and schizophrenic patients (Marsh and Williams, 2006). In addition, N170 impairments have been reported in SCZ patients (Herrmann et al., 2004; Onitsuka et al., 2006), first-degree relatives of SCZ patients (Ibanez et al., 2012a), BD patients (Degabriele et al., 2011) and individuals with ADHD (Ibanez et al., 2011b). To our knowledge, no single study has compared cortical measures of emotional processing in patients with ADHD, BD and SCZ, and the relatives of patients with SCZ.

Theory of mind (ToM) appears to be the bedrock upon which concepts of social cognition are founded. ToM abilities allow individuals to infer and predict the emotional states, beliefs, intentions and reasoning of others. Two of the most widely used ToM tasks are the so-called reading the mind in the eyes task (RME) (Baron-Cohen et al., 1997) and the Faux Pas Test (FPT) (Stone et al., 1998; Baron-Cohen et al., 1999). The RME measures an individual’s ability to infer social emotions. Detection of a faux pas requires both a cognitive component and an emotional one. Impairments in social cognition and ToM abilities have been reported in patients with SCZ and their relatives (de Achaval et al., 2010; Riveros et al., 2010), in euthymic BD patients (Martino et al., 2011) and in individuals with ADHD (Buitelaar et al., 1999; Ibanez et al., 2011b). There have only been reported comparisons of BD and SCZ (Bora et al., 2009).

Emotion, social cognition and cognitive process are finely intertwined (Pessoa, 2009; Millan et al., 2012). The social cognition processes are partially explained by processing speed, executive function and fluid intelligence (Mathersul et al., 2009; Roca et al., 2010; Wilhelm et al., 2010; Huepe et al., 2011). Reports including all neuropsychiatric disorders assessed in this work support the notion that there is an association between emotional processing and cognitive profile, such as fluid intelligence [SCZ: Kalkstein et al. (2010); BD: Balanza-Martinez et al. (2008); Tabares-Seisdedos et al. (2008); ADHD: Tillman et al. (2009)], processing speed [SCZ: Anselmetti et al. (2009), Knowles et al. (2010); BD: Antila et al. (2011); ADHD: Dhar et al. (2010)] and executive functioning [SCZ: Kerns et al. (2008); BD: Joseph et al. (2008), Torralva et al. (2011); ADHD: Doyle (2006), Torralva et al. (2011)]. Although it has previously been hypothesized that emotional processing is intertwined with complex social skills (Itier and Batty, 2009; Grossmann, 2010) and cognitive functioning (Pessoa, 2009), studies indexing this relationship are very uncommon.

The goal of this study

We evaluated if individual differences in an early cortical marker of face and semantic emotional modulation (N170) would be associated with the social-cognitive performance. In short, the emotional N170 modulation (indexed by facial, semantic and face–word stimuli) should be associated with (i) social cognition measures (ToM abilities) and (ii) cognitive measures of fluid intelligence, processing speed and executive functions. In addition, brain signatures of object recognition (e.g. the difference between the N170 amplitude from face and word stimuli), should also be related to fluid intelligence, as already reported in behavioral paradigms (Wilhelm et al., 2010).

This study allowed us to evaluate several new issues. For instance, we compared the early brain markers of facial and semantic processing in SCZ patients, their relatives, ADHD patients, BD patients and healthy volunteers. This was accomplished by comparing the N170 results that were obtained in the DVT between groups. We also compared the neuropsychological profiles in the groups that we studied. This goal was achieved by group comparisons of ToM (RME and FPT) and cognitive performance (fluid intelligence, processing speed and executive functions). In addition, we developed a model of association between emotional N170 modulation (E-N170) and ST N170 (ST-N170) modulation in relation to the SCP of participants. This model was evaluated using structural equation modeling (SEM) because SEM is an ideal technique for combining a measurement model and a structural model into a unified statistical approach (Loon, 2008). SEM allows for the simultaneous testing and estimation of the causal relationships between groups of variables that have been observed. Finally, we tested the relationship between the E-N170 and ST-N170 signals and the SCP of each group (healthy volunteers, SCZ patients and their relatives, BD patients and individuals with ADHD). To test this issue, each group was considered a categorical variable, and cortical measures of emotional processing were subjected to a regression analysis as predictors of the SCP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

In total, 100 participants (67 males, mean age = 39.08 years, s.d. = 11.57 years, 98% right-handed) completed an initial neuropsychiatric interview, a full neuropsychological evaluation, and an electroencephalography (EEG) session in which their responses to the DVT were recorded. A questionnaire was given to all participants to rule out any hearing, visual or other neurological deficits. All of the participants provided written informed consent according to the standards set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki. All of the experimental procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Cognitive Neurology. All of the groups were similar with regard to the age, handedness, gender and IQ (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical, demographic and neuropsychological (cognitive and social cognition measures) assessment

| 1. Controls (n = 41) | 2. SCZ (n = 15) | 3. SFDR (n = 14) | 4. BD (n = 14) | 5. ADHD (n = 16) | P-values (F/χ2) | Post hoc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dem. | |||||||

| Age (years) | 38.3 (11.4) | 38.2 (11.9) | 45.7 (12.4) | 40.4 (9.2) | 34.6 (11.1) | N.S | N.S |

| Gender (F:M) | 15:26 | 3:12 | 8:6 | 5:9 | 2:14 | N.S | N.S |

| Handedness (L:R) | 1:40 | 0:15 | 0:14 | 1:13 | 0:16 | N.S | N.S |

| Clinical profile | |||||||

| Barkley-inattention | 7.5 (7.1) | 14.1 (6.2) | – | – | |||

| Barkley-hyperactivity | 5.9 (7.4) | 13.1 (4.9) | – | – | |||

| BDI-II | 5.2 (6.9) | 11.3 (6.7) | – | – | |||

| YMRS | 0.1 (0.3) | 2.3 (6.1) | – | – | |||

| PANNS | |||||||

| Positive | 18.2 (5.9) | ||||||

| Negative | 98.0 (6.1) | – | – | ||||

| General | 27.2 (11.7) | ||||||

| Social-cognitive measures | |||||||

| Processing speed (TMT-A) | 38.5 (18.0) | 55.0 (24.8) | 41.5 (20.1) | 42.5 (13.2) | 33.4 (10.8) | <0.01 | 1 vs 2* |

| Executive functions (TMT-B) | 76.8 (27.2) | 141.8 (88.4) | 94.7 (55.1) | 82.1 (39.6) | 73.8 (26.5) | <0.01 | 1 vs 2** |

| Fluid intelligence (RPM) | 30.7 (4.9) | 29.6 (4.7) | 29.9 (5.9) | 29.0 (5.4) | 30.9 (5.6) | N.S | N.S |

| Emotional inference (RME) | 26.8 (4.4) | 21.7 (6.0) | 26.3 (7.2) | 25.1 (4.4) | 20.9 (4.3) | =0.08 | 1 vs 2# |

| 1 vs 5# | |||||||

| Cognitive-affective ToM (FPT) | 50.4 (11.0) | 24.8 (14.4) | 30.0 (10.4) | 39.0 (13.9) | 50.31 (6.4) | <0.01 | 1 vs 2** |

| 1 vs 3** | |||||||

| 1 vs 4# | |||||||

* P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; # trend.

Healthy volunteers

In total, 41 healthy participants (26 males, mean age = 38.3 years, s.d. = 11.4 years, one left-handed participant was included as a match for a left-handed BD patient) were recruited from a larger pool of volunteers.

Multiplex SCZ patients

Fifteen schizophrenic patients (12 males, mean age = 38.2 years, s.d. = 11.9 years) were enrolled in this study. Inclusion criteria for these patients were as follows: (i) diagnosis of paranoid SCZ according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) criteria (First et al., 1996) confirmed by the Schedules of Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN) (Wing et al., 1990) and (ii) presence of one or more relatives who also had a diagnosis of SCZ (relatives who were more distant than third-degree relatives were not considered in this criterion) as evidenced from the Family Interview for Genetic Studies (FIGS) to the relatives of the participant (Diaz de Villalvilla et al., 2008). Members of this group were also evaluated using the Positive and Negative Symptoms Scale (PANSS) (Kay et al., 1987). All of the patients in this group were receiving classic antipsychotic medication at the time of participation. Because differences in IQ partially explain several differences that are associated with SCZ (Mesholam-Gately et al., 2009), only those patients whose IQs were within the range of the IQs of the healthy volunteers were included.

First-degree relatives of patients with schizophrenia (SFDRs)

Fourteen siblings (six males, mean age = 45.7 years, s.d. = 12.4 years) were recruited from 10 unique families. For each patient with SCZ, a maximum of two SFDRs were recruited based on the FIGS assessments. Healthy SFDRs had to be first-degree relatives who had never been diagnosed with schizotypal disorders or any other psychiatric disease when they were tested using the SCAN. The SFDRs who were included in the study were not found to be positive for any of the FIGS symptom lists nor had any of them had a prior history of drug use.

ADHD

Sixteen adult participants with ADHD (13 males, mean age = 34.6 years, s.d. = 11.1 years) were recruited for participation in this study. All of the patients fulfilled the DSM-IV criteria for ADHD and were taking methylphenidate medication. Their regular medication schedule was suspended on the day on which the recordings were made. A diagnosis of ADHD was made based on the DSM-IV using the following protocol for adults: (i) patient and informant versions of the ADHD Rating Scale for Adults were given to potential participants (Murphy et al., 2002); and (ii) the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) (Beck et al., 1996) and the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) (Young et al., 1978) were used to assess depression and mania, respectively.

BD

Fourteen adult participants with BD (nine males, mean age = 40.4 years, s.d. = 9.2 years, one person was left-handed) completed the evaluation. All of the participants fulfilled DSM-IV criteria for BD and were diagnosed as being euthymic bipolar patients type II without any co-morbidity. The BDI-II and the YMRS were also used to evaluate depression and mania, respectively, in this group. To exclude possible co-morbid ADHD, the participants were asked to complete the ADHD Rating Scale questionnaire for adults. All of the patients had been euthymic (scores ≤6 on the BDI-II and ≤6 on the YMRS) for at least 8 weeks and had not undergone any changes in either medication type or dosage during the previous 4 months. The patients in this group were not receiving antipsychotic medications.

Social and cognitive neuropsychological assessment

Fluid intelligence

The Standard Progressive Matrices version of Raven’s Progressive Matrices (RPM) (Raven, 2000) was used as a measure of general intelligence or g factor (Garlick, 2002). The RPM included 60 spatial tasks that were divided into five blocks of 12 trials. Participants were asked to complete a series of drawings by identifying relevant features on the basis of the spatial organization of an array of objects.

Processing speed

The trial making test, part A (TMT-A) is considered a robust measure of processing speed (Bowie and Harvey, 2006). Errors on the TMT do not directly contribute to the scoring of this test and are generally not tallied, so the primary variables of interest were the raw scores that were generated based on the reaction time (RT) to completion.

Executive function

Part B of the TMT (TMT-B) is considered a test of executive function (Bowie and Harvey, 2006) that particularly targets mental flexibility (Crowe, 1998).

ToM: Emotional inference

The RME task (Baron-Cohen et al., 1997) comprises 36 photographs of eyes that depict various ‘social emotions’, and each picture is surrounded by five alternatives (one word correctly identifies the emotion that is expressed in the eyes; the other four are distracters).

ToM: Cognitive and affective components

The FPT (Stone et al., 1998; Baron-Cohen et al., 1999) assess an individual’s ability to recognize a social ‘faux pas’. A faux pas occurs when a speaker says something awkward without realizing that the listener may not want to hear what has been said or may be hurt by it. Detection of a faux pas requires an understanding that there might be a difference between the knowledge states of the speaker and the listener and an empathic comprehension of the emotional impact that a statement may have on a listener.

Dual valence task

The DVT (Ibanez et al., 2011a,b, 2012a,b; Petroni et al., 2011) was developed on the basis of previous ERP reports of the implicit association test (Hurtado et al., 2009; Ibanez et al., 2010). Briefly, a two-alternative forced-choice task was displayed on a computer screen, and participants were asked to classify words, faces or face–word pairings according to their valence (positive or negative) as quickly as possible.

A total of 100 happy and angry facial expressions and 100 pleasant and unpleasant word stimuli were included. The happy and angry sets of pictures depicted the same people. Different facial and semantic stimuli were used during training blocks. The arousal, valence, emotional (angry vs happy) and physical properties of the faces had previously been controlled, and the arousal, valence, predictability, content, length and frequency properties of the words had also been controlled in a previous experiment [for details, see Ibanez et al. (2011a)].

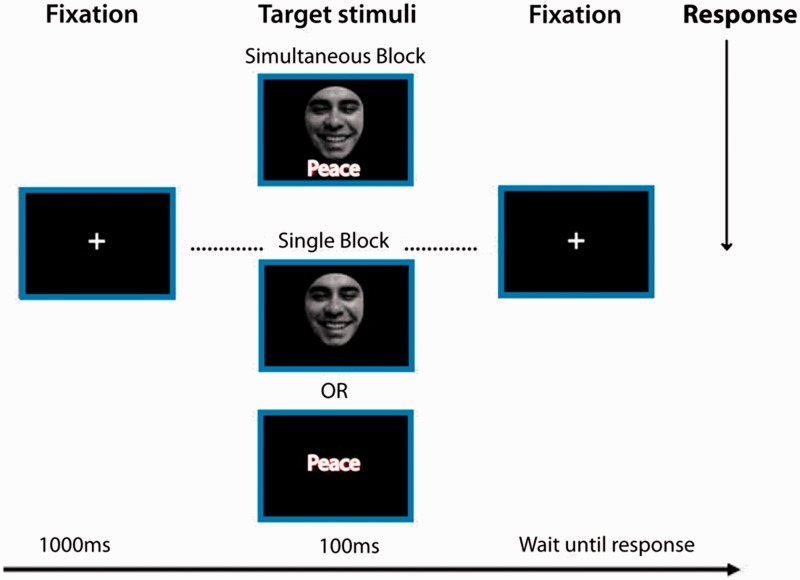

As outlined in Figure 1, a trial began with the presentation of a fixation cross that was 1000 ms in duration, and each stimulus was subsequently presented for 100 ms, after which a fixation cross was presented until the participant responded. Once the participant had made a response, there was an interstimulus interval of 1000 ms. The task comprised two blocks of 200 trials. Blocks of trials were counterbalanced across participants.

Fig. 1.

DVT. The trial begins with the presentation of a fixation cross (1000 ms), followed by the presentation of a target stimulus (100 ms) that consists of a single stimulus face, a single stimulus word, (single stimulus block) or a face and a word that are presented simultaneously (simultaneous stimuli block). A fixation cross was then presented and remained in place until the participant responded. Reproduced from PloS One (Ibanez et al., 2012b).

In the single stimulus block, the participants were shown a single face or a word in the center of the screen on each trial, and they were asked to indicate whether the stimulus was either positive or negative (for both faces and words). Trials in the single stimulus block were presented one at a time, and there was a strict alternation between the presentation of words and faces. On each trial in the simultaneous stimuli block, participants were shown a face (in the center of the screen) and a word (4° below it) simultaneously and for a total of 100 ms. Participants were instructed to indicate whether the face was positive or negative and to ignore the word that was presented below it.

EEG recordings

EEG signals were sampled with HydroCel Sensors from a 129-channels GES300 Electrical Geodesic amplifier at a rate of 500 Hz. Data outside a frequency band ranged from 0.1 to 100 Hz were filtered out during the recording. Later, the data were further filtered using a band-pass digital filter with a range of 0.3–30 Hz to remove any unwanted frequency components. During recording, the vertex was used as the reference electrode by default, but signals were later re-referenced to average electrodes offline. Two bipolar derivations were designed to monitor vertical and horizontal ocular movements (EOG). Continuous EEG data were segmented during a temporal window that began 200 ms prior to the onset of the stimulus and concluded 800 ms after the offset of the stimulus. Eye movement contamination and other artifacts were removed from further analysis using both an automatic (Independent component analysis, ICA) procedure and a visual procedure. No differences were observed between groups regarding the number of trials [F(4, 95) = 1.23, P = 0.91]. All conditions yielded a percentage of artifact-free trials that was at least 87%.

DVT ERP selection

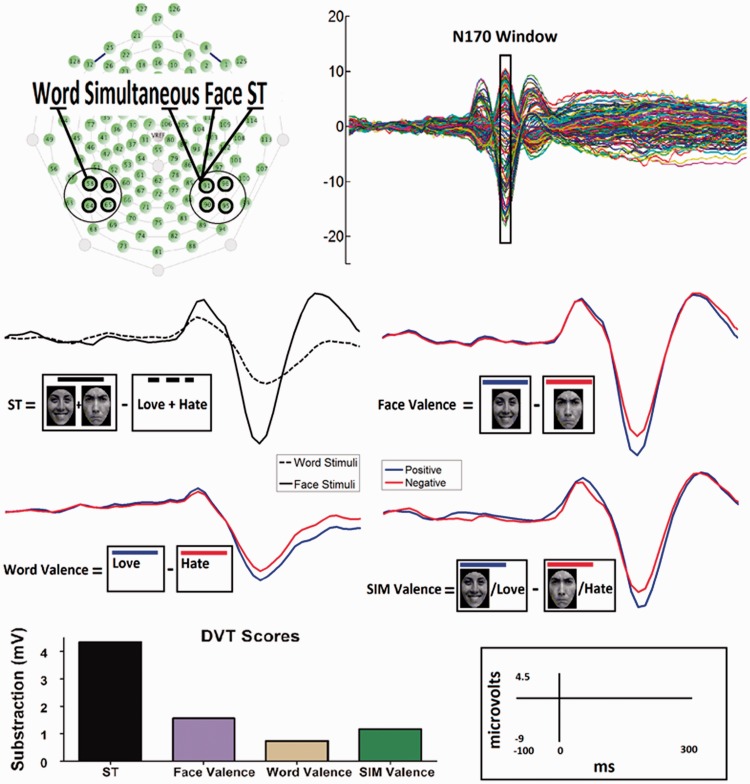

We obtained global scores for both ST (face vs word) and valence (positive vs negative for faces, words and simultaneous stimuli) effects on the basis of previous DVT reports (Ibanez et al., 2011a,b, 2012a; Petroni et al., 2011) by using the mean amplitude of the N170 signal from specific regions of interest (ROIs). Global scores were used for both the ANOVA and SEM analyses. The following procedure (Figure 2) was performed:

Regions of interest: ROIs were chosen by visual inspection to analyze the scalp topography of the ERP components. ROIs comprised four electrodes that were located near the canonical locations for the N170 component [T6 and T7: Rossion and Jacques (2008)]. Consequently, we included four electrodes (the canonical locations and three adjacent electrodes) for each hemisphere (left: 58, 59, 64 and 65; right: 90, 91, 95 and 96; see Figure 2).

Mean amplitude of N170 ROIs: N170 measures were computed by using a fixed temporal window (140–190 ms), after which the mean amplitude of the N170 signal was obtained for the mean of each category and each subject. The modulation of the N170 signal that is observed in the DVT is very sensitive to mean amplitude and is not sensitive to latency (Ibanez et al., 2011a, b, 2012a; Petroni et al., 2011).

Scalp location for stimulus type and valence effects: ST effects and face valence modulation were analyzed according to signals from the right hemisphere (Ibanez et al., 2012). Right hemisphere dominance for face processing has been previously demonstrated (Bentin et al., 1999; Rossion et al., 2003) and confirmed with source studies (Rossion and Gauthier, 2002; Rossion et al., 2003). Valence effects have also been shown to be more prominent in the right N170 signal (Brandeis et al., 1995; Bentin et al., 1999; Boucsein et al., 2001; Rossion et al., 2003; Joyce and Rossion, 2005; Kolassa and Miltner, 2006) [but see bilateral effects: Anes and Kruer (2004)]. The simultaneous valence effect (Ibanez et al., 2011a; Petroni et al., 2011) was reported as being more prominent in the right hemisphere in previous studies. Following previous reports (Simon et al., 2007; Maurer et al., 2008; Mendez-Bertolo et al., 2011), only semantic valence effects were reported from left hemisphere.

Global scores of each component were obtained: A single ST-N170 index was obtained for each subject by performing a face-minus-word subtraction; and for facial valence, word valence and simultaneous valence (E-N170) positive-minus-negative subtractions were performed. Briefly, we selected ROIs in both hemispheres that surrounded the canonical N170 positions, calculated the mean amplitudes of the N170 signals, and calculated the lateralized global scores of the ST-N170 and E-N170 components (Figure 2).

Fig. 2.

Procedure for the N170 global scores extraction from the DVT. This figure shows data preprocessed (low-pass filtered for visualization purposes) from a single normal volunteer. (A) Scalp location of each electrode and electrode selection for each category near the T6 and T7 electrodes. (B) Butterfly montage showing the average temporal window that was selected for further analysis of the N170 signal. (C) The N170 amplitude modulation in response to the DVT categories of face, words and simultaneous stimuli regarding ST and valence. (D) DVT global scores (in µV) that were obtained via category subtraction: ST (face minus word); face valence (positive faces minus negative ones); word valence (positive words minus negative ones); simultaneous valence (positive simultaneous minus negative ones).

Data analysis

Group comparison

ANOVAs and Tukey’s HSD post hoc comparisons (when appropriate) were used to compare the demographic, neuropsychological and RT data across all groups. The chi-square test was used to examine categorical variables (e.g. gender).

Repeated measures ANOVAs and Tukey’s HSD post hoc comparisons (when appropriate) were performed to analyze the DVT ERP data. One within-subjects factor, the global score for ST measures (faces-minus-words), was included. Another within-subjects factor, the global valence score (positive-minus-negative), was included separately for each type of stimulus (face valence, word valence and simultaneous valence). Finally, one between-subjects factor that had five levels was included (group: controls, SCZ, SFDR and ADHD). The Matlab software program and the EEGLab toolbox were used for the offline processing and analysis of the EEG data.

SEM model

The following latent variables (constructs) were defined for use in the SEM on the basis of the theoretical assumptions that have been outlined in the ‘Introduction’ section:

E-N170: The E-N170 construct was understood as a latent variable that was measured using facial, semantic and simultaneous face–word stimuli. We defined this latent variable based on a common factor (emotional modulation) that was assessed using observed variables that referred to different stimuli formats (face valence, word valence and simultaneous valence).

SCP: The social cognition measures of ToM abilities (emotional inference and cognitive-affective components) and the cognitive measures of fluid intelligence, processing speed and executive function formed the construct that was used to measure the SCP. Although we expected the social and cognitive measures to be associated with one another on the basis of previous research, an additional analysis of the SCP goodness of fit was performed to confirm this association. The SCP latent factor was validated using confirmatory factor analysis. The SCP factor represents the common variance of its multiple indicators (RME, FPT, executive function, processing speed and fluid intelligence). A confirmatory factor analysis of these variables resulted in indices that suggested that the fit was good: χ2 = 5.63 (df = 5, P = 0.34), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.036 and comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.99.

We also included an observed variable, the N170 modulation that resulted from object recognition (ST-N170) to evaluate the relative contribution of object recognition to the SCP. Face perception has been linked with intelligence in the past (Wilhelm et al., 2010), so we also proposed that there would be a direct association between the ST-N170 signal and fluid intelligence.

SEM was used to estimate the relationships between the E-N170 and ST-N170 components with the SCP while considering that both the measurement model and the hypothesized causal relationships will be tested simultaneously. This method involves developing a theoretical model that can be used to specify relationships (which are represented using a path diagram) and testing these hypotheses by exploring the degree to which the theoretical model is able to explain the pattern of intercorrelations in a set of variables. Latent factors can represent constructs that are not directly observed but that the model is able to estimate from observed variables (indicators) based on theoretical assumptions regarding which indicator contributes to a particular underlying construct. Indicators that are hypothesized to assess the same construct should have stronger correlations than pairs of indicators that assess different constructs. SEM allows for both the explicit accounting of measurement errors and the accurate estimation of the structural relations between latent factors (Bollen, 1989).

In this study, the SEM analysis was conducted using the M-Plus 6.1 program to estimate model parameters and to test the adequacy of the proposed model (Muthen and Muthen, 2001). The standard errors of the model parameters were calculated using a bootstrap procedure (maximum likelihood method, 95% CIs, 500 bootstrap samples). The extent to which the theoretical model fit the empirical data were quantified using the following goodness of fit statistics: (i) chi-square values and their associated P values (which should not be significant if there is a good model fit); (ii) the RMSEA, which measures the degree to which the model fits the data in the correlation matrix [values that are <0.06 are considered indicative of a good fit (Hu and Bentler, 1999)] and (iii) the CFI, which compares the performance of the specified model to the performance of a baseline (null or independent) model. Values >0.95 are considered to be consistent with an acceptable model fit (Hu and Bentler, 1999).

Auxiliary analysis

To conduct analyses of the specific factors of the already tested SEM general model, we evaluated whether the relation between the E-N170 and ST-N170 scores and the SCP was the same between the different groups of patients. Factor scores were computed and linear regression analysis of the scores that were obtained was performed. Factor scores were calculated using the regression method (Lawley and Maxwell, 1971), and a linear regression model was specified in which the SCP factor score was the dependent variable, and the E-N170 factor score and the observed ST-N170 values were predictors. Interaction terms for the E-N170 × group interaction and the ST-N170 × group interaction were introduced into the model alternatively to assess whether the regression coefficient of either predictor is the same between the patient groups. Using SEM to compare the groups was dismissed because the sample size of each of the groups was not sufficient.

RESULTS

Group comparison of sociodemographic and social-cognitive measures

Table 1 shows the overall results from the demographic, clinical and neuropsychological assessments. No significant differences in age [F(4, 95) = 1.92, P = 0.11], gender [χ2(4) = 0.25, P = 0.58] or handedness [χ2(4) = 2.84, P = 0.58] were observed between the various groups that were studied.

No differences in fluid intelligence were observed between the groups [F(4, 95) = 0.41, P = 0.79], but there was a significant difference in processing speed scores between the groups [TMT-A: F(4, 95) = 3.17, P = 0.01]. Post hoc comparisons (Tukey’s HSD test, MS = 325.55, df = 95.00) showed that SCZ participants had significantly longer response times than controls (P < 0.05). We also observed a significant between-group difference in cognitive flexibility scores, which were used to measure executive functioning [TMT-B: F(4, 95) = 5.98, P < 0.001]. Post hoc comparisons (Tukey’s HSD test, MS = 2208.2, df = 95.00) revealed that SCZ participants also had a significant impairment in cognitive flexibility compared with controls (P < 0.001).

When we compared the performance of the different groups in various social cognition tasks, a between-group trend was observed in the RME task [F(4, 95) = 2.34, P = 0.08], which suggests that there is a subtle difference between the groups that we studied. Post hoc comparisons (Tukey’s HSD test, MS = 66.35, df = 95) yielded a trend toward reduced abilities among ADHD (P = 0.07) and SCZ patients (P = 0.08) compared with normal controls. When comparing the FPT scores, a significant between-group difference was also observed [F(4, 95) = 21.98, P < 0.001], and post hoc comparisons (Tukey’s HSD test, MS = 121.96, df = 95) showed that SCZ patients (P < 0.001) and SFDRs (P < 0.001) had significantly lower FPT scores than control subjects. In addition, a trend (P = 0.08) was observed in BD performance compared with that of controls, which suggests that there are subtle failures in ToM processing among members of this group of patients.

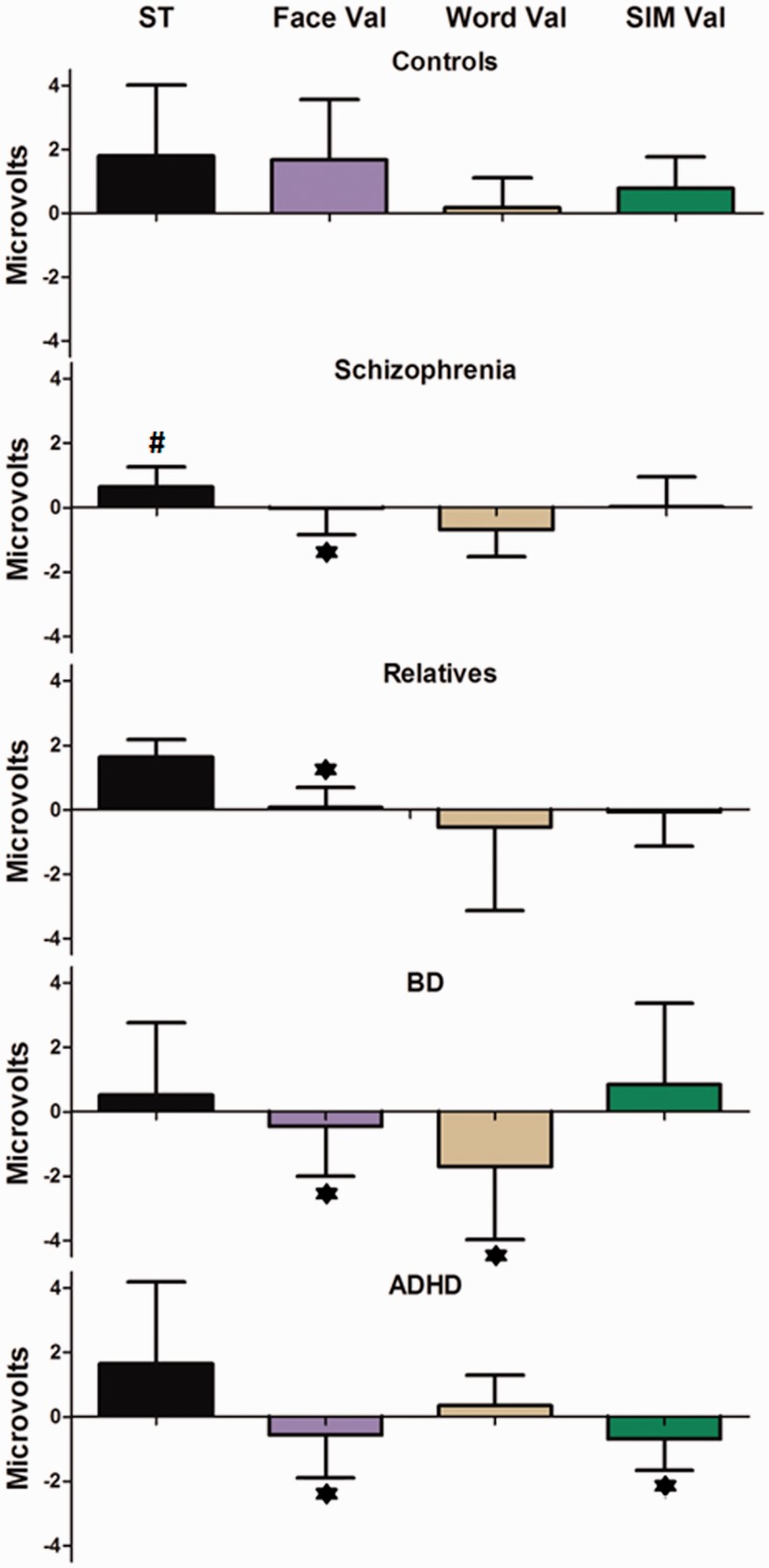

ERPs

Figure 3 illustrates the overall results of the DVT. In all of the affected groups except SCZ (compared with controls), the DVT yielded relatively preserved cortical responses to object recognition stimuli and a generalized impairment in emotional face processing. In addition, a specific abnormality in the processing of semantic stimuli was identified in BD patients, and abnormal processing of simultaneous face–word stimuli was identified among individuals with ADHD.

Fig. 3.

ERP results of the DVT. Global scores for ST, face valence (Face Val), word valence (Word Val) and simultaneous valence (SIM Val) in controls, SCZ, SFDR, BD and ADHD groups. Boxes and bars are indicative of means and s.d., respectively. Asterisks (*) and number sign (#) indicate significant differences and a trend, respectively, in the scores of a particular group regarding those of the control group.

Effects of stimulus type (ST-N170)

A closer look at the ST differences between the groups that were studied suggested that SCZ and BD patients presented reduced object recognition abilities for recognizing faces. Nevertheless, no significant difference—but a trend—between groups was observed [F(4, 95) = 2.49, P = 0.08]. Post hoc comparisons (Tukey’s HSD test, MS = 2.43, df = 95) revealed that there was a trend toward reduced N170 signal for the ST discrimination in SCZ patients (P < 0.07) compared with this signal in controls. Positive scores in all of the groups indicate that the N170 signal amplitude was increased in response to face stimuli compared with word stimuli.

Emotional effects (E-N170)

Face valence

Significant differences between the groups in responses to face valence were observed [F(4, 95) = 10.33, P < 0.0001]. Post hoc comparisons (Tukey’s HSD test, MS = 2.26, df = 95) showed that the global scores of the N170 face emotional effects were reduced in SCZ patients (P < 0.005), SFDRs (P < 0.01), BD patients (P < 0.001) and ADHD patients (P < 0.001) relative to controls.

Word valence

An analysis of the global scores of the word valence effects on the N170 signal demonstrated significant differences between groups [F(4, 95) = 5.18, P < 0.001]. Post hoc comparisons (Tukey’s HSD test, MS = 2.23, df = 95) provided evidence of an inversion of the global scores from the word emotional effects on the N170 component of BD patients (P < 0.005) compared with controls. The negative scores that were obtained from the BD patients indicated that negative valence elicited higher N170 amplitudes than positive valence, which can be taken as evidence of an early negative semantic bias.

Simultaneous valence

The simultaneous presentation of faces and words, also elicited a significant between-groups effect [F(4, 95) = 4.60, P < 0.005]. Post hoc comparisons (Tukey’s HSD test, MS = 1.71, df = 95) revealed that there was a reduced N170 signal for the emotional discrimination of simultaneous stimuli in ADHD patients (P < 0.005) compared with controls. Although smaller global scores were also obtained in the SCZ group and the group of SFDRs, no significant effects were observed in these groups.

The overall DVT results provided evidence of an object-recognition effect that was relatively preserved in all of the affected groups (except by a trend in SCZ patients). In opposition to that, strong deficits in the N170 emotional processing were observed. SCZ patients and their relatives, BD patients and ADHD patients all presented an impaired N170 signal for the discrimination of facial emotions. The BD patients also presented an early semantic valence modulation that indicated the presence of a bias (enhanced N170 amplitude) toward negative words. Finally, the N170 signal from ADHD patients failed in discriminating the valence of simultaneous face–word stimuli, which provides evidence of a deficit in processing emotional stimuli with higher attentional demands.

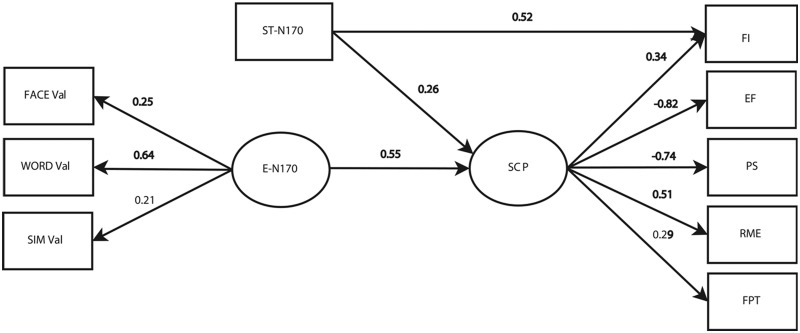

SEM model of E-N170 and ST-N170 association with SCP

Testing the hypothesized associations (Figure 4) resulted in a valid model [χ2(22, n = 100) = 28.3, df = 22, P = 0.16] with good fit indices (RMSEA = 0.054, CFI = 0.96). The standardized path coefficients (regression loadings of one variable on another) are provided within the path diagram. Those that are significant at the P < 0.05 level are bold. The E-N170 scores had a significant and positive association with SCP scores (0.55), which means that participants with higher E-N170 scores also had higher SCP scores. Similarly, ST-N170 had a positive and significant effect on SCP scores (0.26) and a significant direct effect on fluid intelligence (0.52), which implies that there is a relation between the ST-N170 measure and fluid intelligence even when the SCP score is held constant.

Fig. 4.

SEM model. Significant SEM used to test the effects of the E-N170 and STN170 signals on the SCP scores, χ2(22, n = 100) = 28.3, RMSEA = 0.054 and CFI = 0.96. Coefficients that met significance criterion are marked in bold.; Face Val, N170 modulation of facial affect; Word Val, N170 modulation of semantic affect; SIM Val, N170 modulation of simultaneous affect; E-N170, emotional modulation of N170; ST-N170, ST modulation of N170; FI, fluid intelligence; PS, processing speed; EF, executive function; RME, reading the mind in the eyes task; FPT, faux pas test.

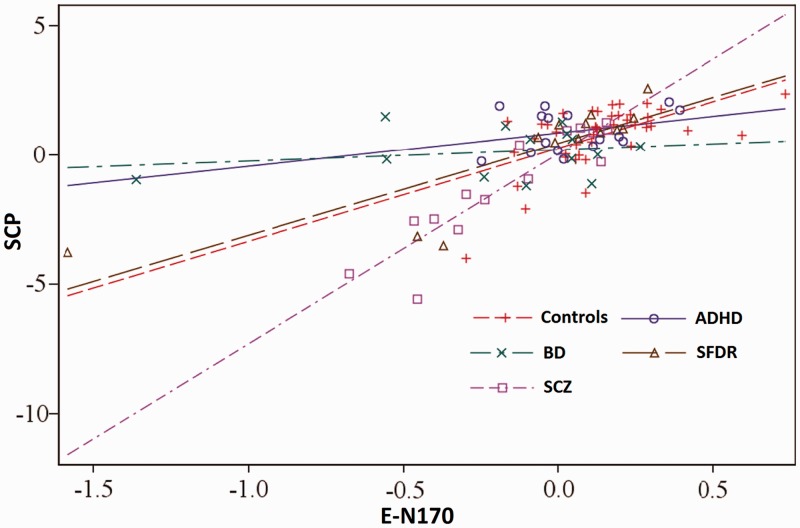

Auxiliary analysis

Linear regression analysis using factor scores for the E-N170 and SCP latent variables, and the ST-N170 scores were employed to assess whether the effects that were encountered using SEM are the same between the different groups. Table 2 shows the regression coefficients (overall and by group) and the associated P-values. There were significant overall effects of both E-N170 and ST-N170 on SCP when interactions between the groups and each of these variables were ignored (regression coefficients; 3.64 and 0.28, respectively).

Table 2.

Regression coefficients of linear regression analysis (E-N170 and ST-N170 scores as predictors of SCP)

| Group | Regression coefficient (P-value) | Interaction between E-N170/ ST-N170 with group (P-value) and comparisons |

|---|---|---|

| E-N170 -> SCP | ||

| Overall | 3.64 (P < 0.001) | F(4, 89) = 9.37; P < 0.0001 |

| SCZ | 7.74 (P < 0.001) | vs controls; P < 0.01 |

| SFDR | 3.54 (P < 0.001) | vs controls; ns |

| BD | 1.10 (P = 0.23) | vs controls; P < 0.01 |

| ADHD | 3.46 (P = 0.01) | vs controls; ns |

| Controls | 4.83 (P < 0.001) | – |

| ST-N170 -> SCP | ||

| Overall | 0.28 (P < 0.001) | F(4, 89) = 1.85; P = 0.12, ns |

| SCZ | 0.54 | – |

| SFDR | 1.06 | – |

| BD | 0.17 | – |

| ADHD | 0.24 | – |

| Controls | 0.26 | – |

The E-N170 × group and ST-N170 × group interaction effects were introduced into the model to assess whether the regression coefficients were the same among the different groups. The results showed that there were statistically significant differences between the regression coefficients of the different groups (overall) for the E-N170 variable [F(4,89) = 9.37, P < 0.0001] but not for the ST-N170 variable [F(4,89) = 1.85, P = 0.12]. In case of the E-N170 regression coefficients, there were statistically significant differences between SCZ and DB patients regarding controls (SCZ > control and BD < control; see Figure 5). The effect of the ST-N170 variable on SCP was relatively homogeneous among the groups that were tested.

Fig. 5.

Auxiliary analysis. Relationship between factor score (E-N170) and the SCPs of each group.

DISCUSSION

We investigated the early cortical processing of emotional stimuli and their relationship with social and cognitive performance through a SEM model among healthy individuals, SCZ patients and their relatives, individuals with ADHD, and BD patients. We found that ERP (E-N170) of emotional stimuli (including face, words and simultaneous face–word parings) predicted the social/cognitive performance (SCP). The E-N170 score was a better predictor of SCP than the object recognition score (ST-N170), and the model provided evidence for an association between social cognition performance (RME and FPT) and cognitive measures (processing speed, fluid intelligence and executive functions) which were identified as elements of a latent variable. Consistent with preliminary evidence of healthy (Herzmann et al., 2010; Hileman et al., 2011) and neuropsychiatric participants (Fernandez-Duque and Black, 2005; de Achaval et al., 2010; Ibanez et al., 2011b; McLaughlin et al., 2011), early automatic brain signatures of emotional processing could be a potential biomarker of basic social cognitive abilities.

At the group level, this is the first comparison of brain markers of emotional processing and social cognition among SCZ patients, SFDRs, individuals with ADHD and BD patients. A shared impairment in brain markers of emotional face processing was found in the affected groups. In addition, BD patients presented an abnormal emotional processing of semantic information, and a specific impairment in the processing of simultaneous emotional stimuli was observed in ADHD patients. A more profound impairment was observed in SCZ patients, in both the E-N170 and ToM measures, as well as in cognitive variables usually associated with social cognition (processing speed and executive function). Regarding ToM abilities, a subtle deficit in emotional inference (RME) was observed in ADHD participants, and both BD patients and SFDRs were found to have deficits in more complex ToM processing (as shown by FPT scores).

Our results suggest that there is a shared cortical impairment in emotional processing among all affected groups which is associated with the social cognition impairments. Regression of emotional biomarkers (SEM scores using E-N170) accurately predicted the performance of all of the groups except the BD group on social and cognitive tasks (SCP). These result are consistent with previous reports of social behavior positive associations with cognitive process (Mathersul et al., 2009; Roca et al., 2010; Wilhelm et al., 2010; Huepe et al., 2011), also observed in different psychiatric conditions (Uekermann et al., 2006, 2007; Uekermann and Daum, 2008; Anselmetti et al., 2009). Thus, our model supports an intrinsic association between emotional cortical processing, ToM abilities and cognitive performance.

Relevance for neuropsychiatric research

Cortical measures of emotional processing

In SCZ patients (Edwards et al., 2002; Kohler et al., 2003; Turetsky et al., 2007) and in SFDRs (de Achaval et al., 2010; Goghari et al., 2011; Ibanez et al., 2012a), several studies have provided evidence of a deeper impairment that affects emotional processing. Abnormalities in face processing and emotion recognition have been reported in BD patients (Getz et al., 2003; Malhi et al., 2007). In addition, enhanced early attentional bias toward negative information is observed in BD (Leppanen, 2006). Regarding comparisons among groups, for ADHD adults and schizophrenic patients there are few studies that have investigated emotional processing, although impairments in both facial recognition and emotional processing have been proposed as possible biomarkers of these conditions (Marsh and Williams, 2006). Some studies have compared emotional impairment in children with ADHD and BD and have shown that both groups of children have deficits (Brotman et al., 2010; Passarotti et al., 2010a,b). Schizophrenic patients have higher deficits than BD in affect recognition and facial recognition (Addington and Addington, 1998). Finally, regarding the N170, our study confirms impairments in families of SCZ patients (Ibanez et al., 2012a), BD (Ibanez et al., 2012b) and ADHD patients (Ibanez et al., 2011b).

Our results provide the first comparison of these groups, suggesting that impairments of N170 emotional modulation may be a transdiagnostic affected dimension. We confirmed the N170 deficits in SCZ families, and the negative bias reported in BD patients. ADHD participants presented impairments in the processing of simultaneous stimuli, which suggests that they have difficulties with integrating facial and semantic emotional information that are due to divided attention or other distraction factors.

Social cognition

Previous reports (de Achaval et al., 2010) have provided evidence that SCZ patients presented impairments in tests of emotional inference (RME) as well as complex ToM skills (as measured by the FPT). Consistent with previous studies (de Achaval et al., 2010; Riveros et al., 2010) SFDRs showed abnormalities in performance on the FPT. We also found a trend toward reduced effects regarding performance on social cognition tasks in ADHD patients relative to controls (Buitelaar et al., 1999; Ibanez et al., 2011b). Similarly, and in accordance with previous studies (Martino et al., 2011), our results suggest that euthymic BD patients show impairments in FPT performance but not in RME test performance.

Only a few previous studies have compared ToM functioning in some of the psychiatric conditions reported here [e.g. one study described ToM abnormalities in both BD and SCZ (Bora et al., 2009)]. Our results suggest a strong emotional and cognitive ToM impairment in SCZ that is attenuated among SFDRs. ADHD presented subtle impairment in ToM emotional inference and simultaneous valence impairment at N170 level. Possibly, distraction factors or divided attention could explain these results because both tasks required the integration of semantic and facial valence. Finally, only more complex levels of cognitive-affective ToM skills appear to have been impaired in BD patients; this impairment appears to occur in conjunction with a negative bias in the cortical processing of emotions.

Dimensionality, gene–environment interactions and biomarkers in transdiagnostic research

Emotional processing and social cognition are important areas of transdiagnostic research (McLaughlin et al., 2011). Our study suggests that the E-N170 score may be considered a possible biomarker of social and cognitive deficits in SCZ patients. In BD, emotional impairments are considered are an emerging area (McLaughlin et al., 2011) and the negative bias needs to be further assessed. The positive association between the E-N170 and SCP scores was significant also in ADHD patients, SFDRs and controls, opening new branches for additional research.

Common genetic backgrounds and shared symptomatology with respect to the neurocognitive profiles have been proposed for SCZ families (van Rijn et al., 2005), BD and SCZ (Hill et al., 2008), ADHD and SCZ (Marsh and Williams, 2006) and ADHD and BD (Passarotti and Pavuluri, 2011). These disorders share some symptoms, are often co-morbid, and present emotional processing impairments. The combination of behavioral and neural markers of emotional, social and cognitive processing can be a powerful approach in transdiagnostic research. Future studies combining genetic assessments with neurocognitive markers of emotional processing and social cognition as common dimensions would shed light on a possible shared genetic vulnerability in different psychiatric conditions.

Limitations and further remarks

The groups of patients were relatively small for a variety of reasons (stringent inclusion criteria, exclusion of comorbidities, control for affective symptoms, and matching of patients with healthy controls according to age, IQ, gender, educational level and handedness). Because there were only a moderate number of participants, the possibility of using SEM to generate a multi-group model was dismissed. Future studies should evaluate the SEM model of emotional biomarkers and SCPs that was developed in this study in a larger sample. As in almost all previous studies, SCZ and BD patients in this study were taking medications, so we cannot discount the influence of these drugs on cognitive function. Nevertheless, we only included SCZ patients who were taking classical medications and excluded any BD patients who were taking antipsychotic medications. Also, the normal medication that was taken by the ADHD patients in our study was suspended on the day on which recordings were made. Further assessment of the effects of medication as a possible moderator variable in the present SEM model is a topic for future research.

CONCLUSION

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to report an association model of early cortical markers of emotional processing and social-cognitive performance. It is also the first to compare patients from several psychiatric groups that have shared emotional and social cognition impairments. Both issues would promote novel pathways for clinical research as well as theoretical models of affective-cognitive neuroscience.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants Comisión Nacional de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica (CONICYT) fellowship for PhD studies (R.O.) CONICYT/FONDECYT Regular (1090610 to V.L. and 1130920 to A.I.), Fondo para la Investigación Científica y Tecnológica (FONCyT-PICT) 2012-0412 (F.M.), FONCyT-PICT 2012-1309 (A.I.), James McDonnell Foundation (M.S.), Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET) and INECO Foundation.

REFERENCES

- Addington J, Addington D. Facial affect recognition and information processing in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophrenia Research. 1998;32(3):171–81. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolphs R. Cognitive neuroscience of human social behaviour. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2003;4(3):165–78. doi: 10.1038/nrn1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolphs R. The social brain: neural basis of social knowledge. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:693–716. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolphs R. Conceptual challenges and directions for social neuroscience. Neuron. 2010;65(6):752–67. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolphs R, Skuse D. Special issue of Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience (December, 2006) genetic, comparative and cognitive studies of social behavior. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2006;1(3):163–4. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsl038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anes MD, Kruer JL. Investigating hemispheric specialization in a novel face-word Stroop task. Brain and Language. 2004;89(1):136–41. doi: 10.1016/S0093-934X(03)00311-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anselmetti S, Bechi M, Bosia M, et al. ‘Theory’ of mind impairment in patients affected by schizophrenia and in their parents. Schizophrenia Research. 2009;115(2–3):278–85. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antila M, Kieseppa T, Partonen T, Lonnqvist J, Tuulio-Henriksson A. The effect of processing speed on cognitive functioning in patients with familial bipolar I disorder and their unaffected relatives. Psychopathology. 2011;44(1):40–5. doi: 10.1159/000317577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashley V, Vuilleumier P, Swick D. Time course and specificity of event-related potentials to emotional expressions. Neuroreport. 2004;15(1):211–6. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200401190-00041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson AP, Adolphs R. The neuropsychology of face perception: beyond simple dissociations and functional selectivity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B Biological Sciences. 2011;366(1571):1726–38. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balanza-Martinez V, Rubio C, Selva-Vera G, et al. Neurocognitive endophenotypes (endophenocognitypes) from studies of relatives of bipolar disorder subjects: a systematic review. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2008;32(8):1426–38. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S, Jolliffe T, Mortimore C, Robertson M. Another advanced test of theory of mind: evidence from very high functioning adults with autism or asperger syndrome. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997;38(7):813–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S, O'Riordan M, Stone V, Jones R, Plaisted K. Recognition of faux pas by normally developing children and children with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1999;29(5):407–18. doi: 10.1023/a:1023035012436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett LF, Lindquist KA, Gendron M. Language as context for the perception of emotion. Trends in Cognitive Science. 2007;11(8):327–32. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri W. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories-IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Personality Assessmennt. 1996;67(3):588–97. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentin S, Allison T, Puce A, Perez E, McCarthy G. Electrophysiological studies of face perception in humans. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 1996;8(6):551–65. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1996.8.6.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentin S, Mouchetant-Rostaing Y, Giard MH, Echallier JF, Pernier J. ERP manifestations of processing printed words at different psycholinguistic levels: time course and scalp distribution. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 1999;11(3):235–60. doi: 10.1162/089892999563373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besnier N, Kaladjian A, Mazzola-Pomietto P, et al. Differential responses to emotional interference in paranoid schizophrenia and bipolar mania. Psychopathology. 2011;44(1):1–11. doi: 10.1159/000322097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. Structural Equations with Latent Variables. New York: Wiley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bora E, Yucel M, Pantelis C. Theory of mind impairment: a distinct trait-marker for schizophrenia spectrum disorders and bipolar disorder? Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2009;120(4):253–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botzel K, Schulze S, Stodieck SR. Scalp topography and analysis of intracranial sources of face-evoked potentials. Experimental Brain Research. 1995;104(1):135–43. doi: 10.1007/BF00229863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucsein W, Schaefer F, Sokolov EN, Schroder C, Furedy JJ. The color-vision approach to emotional space: cortical evoked potential data. Integrative Physiological and Behavioral Science. 2001;36(2):137–53. doi: 10.1007/BF02734047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie CR, Harvey PD. Administration and interpretation of the Trail Making Test. Nature Protocols. 2006;1(5):2277–81. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandeis D, Lehmann D, Michel CM, Mingrone W. Mapping event-related brain potential microstates to sentence endings. Brain Topography. 1995;8(2):145–59. doi: 10.1007/BF01199778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotman MA, Rich BA, Guyer AE, et al. Amygdala activation during emotion processing of neutral faces in children with severe mood dysregulation versus ADHD or bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167(1):61–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09010043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buitelaar JK, van der Wees M, Swaab-Barneveld H, van der Gaag RJ. Theory of mind and emotion-recognition functioning in autistic spectrum disorders and in psychiatric control and normal children. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11(1):39–58. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499001947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calder A, Rhodes G, Johnson M, Haxby J. Oxford Handbook of Face Perception. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Crowe SF. The differential contribution of mental tracking, cognitive flexibility, visual search, and motor speed to performance on parts A and B of the Trail Making Test. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1998;54(5):585–91. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(199808)54:5<585::aid-jclp4>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Achaval D, Costanzo EY, Villarreal M, et al. Emotion processing and theory of mind in schizophrenia patients and their unaffected first-degree relatives. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48(5):1209–15. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deffke I, Sander T, Heidenreich J, et al. MEG/EEG sources of the 170-ms response to faces are co-localized in the fusiform gyrus. Neuroimage. 2007;35(4):1495–501. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degabriele R, Lagopoulos J, Malhi G. Neural correlates of emotional face processing in bipolar disorder: an event-related potential study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;133(1–2):212–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar M, Been PH, Minderaa RB, Althaus M. Information processing differences and similarities in adults with dyslexia and adults with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder during a Continuous Performance Test: a study of cortical potentials. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48(10):3045–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz de Villalvilla T, Mendoza Quinones R, Martin Reyes M, et al. Spanish version of the Family Interview for Genetic Studies (FIGS) Actas españolas de psiquiatría. 2008;36(1):20–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle AE. Executive functions in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2006;67(Suppl. 8):21–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J, Jackson HJ, Pattison PE. Emotion recognition via facial expression and affective prosody in schizophrenia: a methodological review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2002;22(6):789–832. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(02)00130-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Duque D, Black SE. Impaired recognition of negative facial emotions in patients with frontotemporal dementia. Neuropsychologia. 2005;43(11):1673–87. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Donovan S, Frances A. Nosology of chronic mood disorders. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 1996;19(1):29–39. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70271-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garlick D. Understanding the nature of the general factor of intelligence: the role of individual differences in neural plasticity as an explanatory mechanism. Psychology Review. 2002;109(1):116–36. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.109.1.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getz GE, Shear PK, Strakowski SM. Facial affect recognition deficits in bipolar disorder. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2003;9(4):623–32. doi: 10.1017/S1355617703940021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goghari VM, Macdonald AW, 3rd, Sponheim SR. Temporal lobe structures and facial emotion recognition in schizophrenia patients and nonpsychotic relatives. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2011;37(6):1281–94. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann T. The development of emotion perception in face and voice during infancy. Restorative Neurology and Neuroscience. 2010;28(2):219–36. doi: 10.3233/RNN-2010-0499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann MJ, Ellgring H, Fallgatter AJ. Early-stage face processing dysfunction in patients with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161(5):915–17. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.5.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzmann G, Kunina O, Sommer W, Wilhelm O. Individual differences in face cognition: brain-behavior relationships. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2010;22(3):571–89. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hileman CM, Henderson H, Mundy P, Newell L, Jaime M. Developmental and individual differences on the P1 and N170 ERP components in children with and without autism. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2011;36(2):214–36. doi: 10.1080/87565641.2010.549870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill SK, Harris MS, Herbener ES, Pavuluri M, Sweeney JA. Neurocognitive allied phenotypes for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2008;34(4):743–59. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Huepe D, Roca M, Salas N, et al. Fluid intelligence and psychosocial outcome: from logical problem solving to social adaptation. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e24858. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado E, Haye A, Gonzalez R, Manes F, Ibanez A. Contextual blending of ingroup/outgroup face stimuli and word valence: LPP modulation and convergence of measures. BMC Neuroscience. 2009;10:69. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-10-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibanez A, Gleichgerrcht E, Hurtado E, Gonzalez R, Haye A, Manes FF. Early neural markers of implicit attitudes: N170 modulated by intergroup and evaluative contexts in IAT. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2010;4:188. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2010.00188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibanez A, Hurtado E, Riveros R, et al. Facial and semantic emotional interference: a pilot study on the behavioral and cortical responses to the Dual Valence Association Task. Behavioral and Brain Functions. 2011a;7:8. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-7-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibanez A, Manes F. Contextual social cognition and the behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2012;78(17):1354–62. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182518375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibanez A, Melloni M, Huepe D, et al. What event-related potentials (ERPs) bring to social neuroscience? Social Neuroscience. 2012;7(6):632–49. doi: 10.1080/17470919.2012.691078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibanez A, Petroni A, Urquina H, et al. Cortical deficits of emotional face processing in adults with ADHD: its relation to social cognition and executive function. Social Neuroscience. 2011b;6(5–6):464–81. doi: 10.1080/17470919.2011.620769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibanez A, Riveros R, Hurtado E, et al. The face and its emotion: right N170 deficits in structural processing and early emotional discrimination in schizophrenic patients and relatives. Psychiatry Research. 2012a;195(1–2):18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibanez A, Urquina H, Petroni A, et al. Neural processing of emotional facial and semantic expressions in euthymic bipolar disorder (BD) and its association with theory of mind (ToM) PLoS One. 2012b;7(10):e46877. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itier RJ, Batty M. Neural bases of eye and gaze processing: the core of social cognition. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2009;33(6):843–63. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph MF, Frazier TW, Youngstrom EA, Soares JC. A quantitative and qualitative review of neurocognitive performance in pediatric bipolar disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2008;18(6):595–605. doi: 10.1089/cap.2008.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce C, Rossion B. The face-sensitive N170 and VPP components manifest the same brain processes: the effect of reference electrode site. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2005;116(11):2613–31. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalkstein S, Hurford I, Gur RC. Neurocognition in schizophrenia. Current Topics in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2010;4:373–90. doi: 10.1007/7854_2010_42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1987;13(2):261–76. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns JG, Nuechterlein KH, Braver TS, Barch DM. Executive functioning component mechanisms and schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;64(1):26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles EE, David AS, Reichenberg A. Processing speed deficits in schizophrenia: reexamining the evidence. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167(7):828–35. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09070937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler CG, Hoffman LJ, Eastman LB, Healey K, Moberg PJ. Facial emotion perception in depression and bipolar disorder: a quantitative review. Psychiatry Research. 2011;188(3):303–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler CG, Turner TH, Bilker WB, et al. Facial emotion recognition in schizophrenia: intensity effects and error pattern. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160(10):1768–74. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.10.1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolassa IT, Miltner WH. Psychophysiological correlates of face processing in social phobia. Brain Research. 2006;1118(1):130–41. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawley DN, Maxwell AE. Factor Analysis as a Statistical Method. London: Butterworths; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Leppanen JM. Emotional information processing in mood disorders: a review of behavioral and neuroimaging findings. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2006;19(1):34–9. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000191500.46411.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loon S. Issues and procedures in adopting structural equation modeling technique. Journal of Applied Quantitative Methods. 2008;3(1):76–83. [Google Scholar]

- Malhi GS, Lagopoulos J, Sachdev PS, Ivanovski B, Shnier R, Ketter T. Is a lack of disgust something to fear? A functional magnetic resonance imaging facial emotion recognition study in euthymic bipolar disorder patients. Bipolar Disorder. 2007;9(4):345–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh PJ, Williams LM. ADHD and schizophrenia phenomenology: visual scanpaths to emotional faces as a potential psychophysiological marker? Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2006;30(5):651–65. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino DJ, Strejilevich SA, Fassi G, Marengo E, Igoa A. Theory of mind and facial emotion recognition in euthymic bipolar I and bipolar II disorders. Psychiatry Research. 2011;189(3):379–84. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathersul D, Palmer DM, Gur RC, et al. Explicit identification and implicit recognition of facial emotions: II. Core domains and relationships with general cognition. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2009;31(3):278–91. doi: 10.1080/13803390802043619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer U, Rossion B, McCandliss BD. Category specificity in early perception: face and word n170 responses differ in both lateralization and habituation properties. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2008;2:18. doi: 10.3389/neuro.09.018.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Hatzenbuehler ML, Mennin DS, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Emotion dysregulation and adolescent psychopathology: a prospective study. Behavioral Research and Therapy. 2011;49(9):544–54. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez-Bertolo C, Pozo MA, Hinojosa JA. Early effects of emotion on word immediate repetition priming: electrophysiological and source localization evidence. Cognitive Affective and Behavioral Neuroscience. 2011;11(4):652–65. doi: 10.3758/s13415-011-0059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesholam-Gately RI, Giuliano AJ, Goff KP, Faraone SV, Seidman LJ. Neurocognition in first-episode schizophrenia: a meta-analytic review. Neuropsychology. 2009;23(3):315–36. doi: 10.1037/a0014708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan MJ, Agid Y, Brune M, et al. Cognitive dysfunction in psychiatric disorders: characteristics, causes and the quest for improved therapy. Nature Review Drug Discovery. 2012;11(2):141–68. doi: 10.1038/nrd3628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy KR, Barkley RA, Bush T. Young adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: subtype differences in comorbidity, educational, and clinical history. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2002;190(3):147–57. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200203000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus: Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables: User's Guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Onitsuka T, Niznikiewicz MA, Spencer KM, et al. Functional and structural deficits in brain regions subserving face perception in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(3):455–62. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passarotti AM, Pavuluri MN. Brain functional domains inform therapeutic interventions in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and pediatric bipolar disorder. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 2011;11(6):897–914. doi: 10.1586/ern.11.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passarotti AM, Sweeney JA, Pavuluri MN. Differential engagement of cognitive and affective neural systems in pediatric bipolar disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2010a;16(1):106–17. doi: 10.1017/S1355617709991019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passarotti AM, Sweeney JA, Pavuluri MN. Emotion processing influences working memory circuits in pediatric bipolar disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010b;49(10):1064–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessoa L. How do emotion and motivation direct executive control? Trends in Cognitive Science. 2009;13(4):160–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petroni A, Canales-Johnson A, Urquina H, et al. The cortical processing of facial emotional expression is associated with social cognition skills and executive functioning: a preliminary study. Neuroscience Letters. 2011;505(1):41–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven J. The Raven's progressive matrices: change and stability over culture and time. Cognitive Psychology. 2000;41(1):1–48. doi: 10.1006/cogp.1999.0735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Righart R, de Gelder B. Rapid influence of emotional scenes on encoding of facial expressions: an ERP study. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2008a;3(3):270–8. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsn021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Righart R, de Gelder B. Recognition of facial expressions is influenced by emotional scene gist. Cognitive Affective and Behavioral Neuroscience. 2008b;8(3):264–72. doi: 10.3758/cabn.8.3.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riveros R, Manes F, Hurtado E, et al. Context-sensitive social cognition is impaired in schizophrenic patients and their healthy relatives. Schizophrenia Research. 2010;116(2–3):297–8. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roca M, Parr A, Thompson R, et al. Executive function and fluid intelligence after frontal lobe lesions. Brain. 2010;133(Pt 1):234–47. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossion B, Gauthier I. How does the brain process upright and inverted faces? Behavioral and Cognitive Neuroscience Reviews. 2002;1(1):63–75. doi: 10.1177/1534582302001001004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossion B, Jacques C. Does physical interstimulus variance account for early electrophysiological face sensitive responses in the human brain? Ten lessons on the N170. Neuroimage. 2008;39(4):1959–79. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossion B, Joyce CA, Cottrell GW, Tarr MJ. Early lateralization and orientation tuning for face, word, and object processing in the visual cortex. Neuroimage. 2003;20(3):1609–24. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatinelli D, Fortune EE, Li Q, et al. Emotional perception: meta-analyses of face and natural scene processing. Neuroimage. 2011;54(3):2524–33. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh B, Zhdanov A, Podlipsky I, Hendler T, Yovel G. The validity of the face-selective ERP N170 component during simultaneous recording with functional MRI. Neuroimage. 2008;42(2):778–86. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.04.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Said CP, Haxby JV, Todorov A. Brain systems for assessing the affective value of faces. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B Biological Sciences. 2011;366(1571):1660–70. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon G, Petit L, Bernard C, Rebai M. N170 ERPs could represent a logographic processing strategy in visual word recognition. Behavioral Brain Function. 2007;3:21. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-3-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone VE, Baron-Cohen S, Knight RT. Frontal lobe contributions to theory of mind. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 1998;10(5):640–56. doi: 10.1162/089892998562942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabares-Seisdedos R, Balanza-Martinez V, Sanchez-Moreno J, et al. Neurocognitive and clinical predictors of functional outcome in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder at one-year follow-up. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2008;109(3):286–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.12.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SF, Macdonald AW., 3rd Brain mapping biomarkers of socio-emotional processing in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2011;38(1):73–80. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillman CM, Bohlin G, Sorensen L, Lundervold AJ. Intellectual deficits in children with ADHD beyond central executive and non-executive functions. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2009;24(8):769–82. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acp075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torralva T, Gleichgerrcht E, Torrente F, et al. Neuropsychological functioning in adult bipolar disorder and ADHD patients: a comparative study. Psychiatry Research. 2011;186(2–3):261–6. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turetsky BI, Kohler CG, Indersmitten T, Bhati MT, Charbonnier D, Gur RC. Facial emotion recognition in schizophrenia: when and why does it go awry? Schizophrenia Research. 2007;94(1–3):253–63. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uekermann J, Channon S, Daum I. Humor processing, mentalizing, and executive function in normal aging. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2006;12(2):184–91. doi: 10.1017/S1355617706060280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uekermann J, Channon S, Winkel K, Schlebusch P, Daum I. Theory of mind, humour processing and executive functioning in alcoholism. Addiction. 2007;102(2):232–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uekermann J, Daum I. Social cognition in alcoholism: a link to prefrontal cortex dysfunction? Addiction. 2008;103(5):726–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rijn S, Aleman A, Swaab H, Kahn RS. Neurobiology of emotion and high risk for schizophrenia: role of the amygdala and the X-chromosome. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2005;29(3):385–97. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm O, Herzmann G, Kunina O, Danthiir V, Schacht A, Sommer W. Individual differences in perceiving and recognizing faces-One element of social cognition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;99(3):530–48. doi: 10.1037/a0019972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing JK, Babor T, Brugha T, et al. SCAN. Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1990;47(6):589–93. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810180089012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1978;133:429–35. doi: 10.1192/bjp.133.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]