INTRODUCTION

The recognition of acute life-threatening cardiotoxicity of bupivacaine[1,2] led to the search for a local anaesthetic agent comparable with bupivacaine but with lower cardiotoxicity resulting in development of a relatively new amide, ropivacaine, registered for use in 1996,[1] but introduced in India only in 2009.

Ropivacaine is produced as pure ‘S’ enantiomer with lower lipid solubility, easier reversibility after inadvertent intravascular injection, significant reduction in central nervous system toxicity, lesser motor block and greater differentiation of sensory and motor block.[3]

In equal concentrations, ropivacaine and bupivacaine produced similar sensory and motor block after epidural administration with slightly longer block duration with bupivacaine.[4] Increasing concentrations caused quicker onset, greater intensity, slower regression, and longer duration of motor blockade.[5] Motor blockade of 0.75% ropivacaine was comparable to 0.5% bupivacaine.[6]

The purpose of this study was to evaluate 0.75% ropivacaine as a local anaesthetic in terms of duration and quality of epidural anaesthesia for lower extremity surgeries and compare these effects with 0.5% bupivacaine.

METHODS

A randomised prospective clinical study of patients undergoing elective lower limb orthopaedic surgeries receiving either epidural ropivacaine or bupivacaine was undertaken after obtaining written informed consent and institutional ethical committee approval.

Hundred patients divided into two groups of 50 by pre-decided randomisation schedule, Group R to receive 20 ml of 0.75% ropivacaine and Group B to receive 20 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine.

We included adult patients aged between 18 and 60 years of both sexes of American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) physical status Grade I and II for the study. Exclusion criteria included known allergy to local anaesthetics, local infections, coagulopathy, mental illness, and patients on antiarrhythmic treatment. All patients were of average Indian height and weight.

After pre anaesthestic checkup, patients were kept fasting from previous night and premedicated with tablet ranitidine 150 mg and tablet alprazolam 0.5 mg.

All epidural blocks were performed under strict aseptic precautions in lateral or sitting position and 18 G epidural needle was inserted either in L2-3 or L3-4 interspace (midline approach). After 3 min of test dose of 3 ml 2% lignocaine with adrenaline 1:200,000, in absence of signs of subarachnoid and intravascular injection, 20 ml of test drug was administered over 2 min in increments, after negative aspiration for blood and cerebrospinal fluid. Time of completion of injection of drug was recorded as 0 min.

The height of block required was fixed uniformly as T10, though in most cases a lesser height was required. Sensory blockade was assessed by pin prick using a blunt tipped 26 G needle and onset of sensory block (time from epidural injection to the time T12 blockade was achieved), maximum height reached, time for two segment regression and time to rescue analgesia were noted. The duration of analgesia was time at which patient requested first analgesic. Motor block was assessed using modified Bromage scale[4] and graded as 0: No motor paralysis, 1: Inability to raise extended leg, 2: Inability to flex knee, 3: Inability to flex ankle. Time for onset of motor block (time from epidural injection to the time Bromage Grade 0 changed to Grade 1), maximum motor block and complete motor recovery noted. Sensory and motor block assessed every 5 min for initial 15 min, every 15 min till 90 min and every 30 min to end of surgery, unless sedation or restricted access during surgery prevented it. Tourniquet was used by the surgeons, depending on the nature of the case and feasibility of tourniquet. Patients were monitored for intraoperative events like hypotension, bradycardia, shivering, nausea and vomiting and followed-up for 24 h for any postoperative complications. The quality of analgesia was assessed by time to rescue analgesia.

All statistical methods carried out using SPSS for Windows, 2007, Version 16.0. Chicago, SPSS Inc.

RESULTS

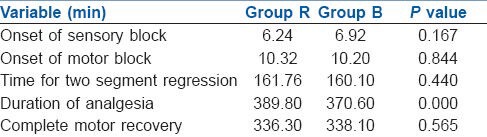

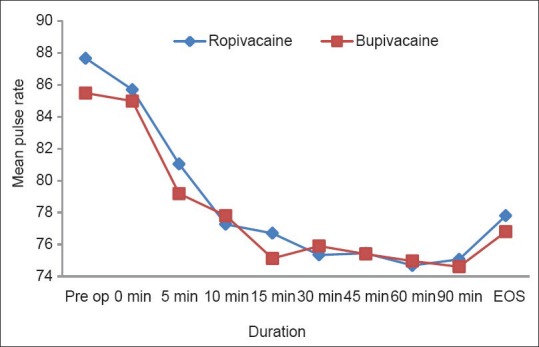

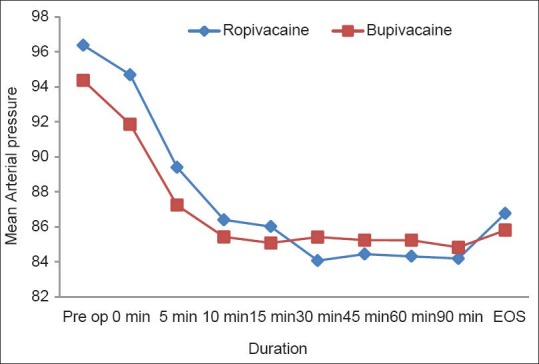

Demographic profiles, mean duration of surgery, the types of surgeries and mean time for onset of sensory and motor block was comparable [Table 1]. In both groups, maximum sensory level reached was T8 with modified Bromage scale 2 in majority cases [Table 1]. Time for two segment regression of sensory block and complete motor recovery in both groups was comparable. In 64% of patients of Group R, time to rescue analgesia was between 390 and 450 min, compared to only 18% in Group B. A maximum of 450 min was seen in one case of Group R. In Group R, the mean duration of analgesia was 389.80 min and 370.60 min in Group B. This was statistically significant. Haemodynamic variables were comparable in both groups [Figures 1 and 2].

Table 1.

Sensory and motor characteristics

Figure 1.

Mean pulse rate

Figure 2.

Mean arterial pressure

DISCUSSION

Epidural anaesthesia reduces perioperative physiologic responses in addition to providing pain relief. Ropivacaine was identified in 1957, but not evaluated fully until 1988 after the alarming editorial by Albright observing difficult resuscitation and poor outcome after accidental intravascular injection of bupivacaine.[7]

In the present study, in patients who received ropivacaine the mean onset time of sensory block was faster than in those who received bupivacaine, but this was not statistically significant. In a similar study, Finucane et al.[8] found that onset time for sensory block to T12 was shorter in 0.75% ropivacaine group when compared to 0.5% bupivacaine group. The mean maximum sensory level reached in present study was T8 in both groups with the volume administered. Time of onset of motor block between two groups was not statistically significant. Brockway et al.[9] showed that motor block produced by ropivacaine was slower in onset. Other studies reported that onset of motor block was quicker with increasing concentrations.[5,6] Time for two segment regression of sensory block in both groups was comparable. Concepcion et al.[5] found a mean time for two segment regression as 164 ± 22 min for 0.75% ropivacaine, which was comparable to present study. Mean time to rescue analgesia in present study was 389.80 min in Group R and 370.60 min in Group B.

The mean time for complete motor recovery in present study was comparable in both groups. Brown et al.[4] and Cekmen et al.[10] showed that duration of motor block was significantly longer in the 0.5% bupivacaine group as compared to 0.5% ropivacaine. Zaric et al.[6] found that motor blockade with 0.75% ropivacaine was comparable to 0.5% bupivacaine.

There were no significant changes in mean pulse rate and mean arterial pressure between two groups in present study, findings shared by other studies.[4,5,9]

There were no postoperative sequelae like headache, backache, nausea and vomiting for next 24 h.

CONCLUSION

It is important that new local anaesthetics that have lower cardiotoxicity are adopted to ensure that regional techniques using large amounts of local anaesthetics remain safe with minimal complications. In the present study using 0.75% ropivacaine and 0.5% bupivacaine epidurally, there were no significant differences in the block parameters but ropivacaine was associated with relatively longer duration of postoperative analgesia.

REFERENCES

- 1.Whiteside JB, Wildsmith JA. Developments in local anaesthetic drugs. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:27–35. doi: 10.1093/bja/87.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leone S, Di Cianni S, Casati A, Fanelli G. Pharmacology, toxicology, and clinical use of new long acting local anesthetics, ropivacaine and levobupivacaine. Acta Biomed. 2008;79:92–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stienstra R. The place of ropivacaine in anesthesia. Acta Anaesthesiol Belg. 2003;54:141–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown DL, Carpenter RL, Thompson GE. Comparison of 0.5% ropivacaine and 0.5% bupivacaine for epidural anesthesia in patients undergoing lower-extremity surgery. Anesthesiology. 1990;72:633–6. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199004000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Concepcion M, Arthur GR, Steele SM, Bader AM, Covino BG. A new local anesthetic, ropivacaine. Its epidural effects in humans. Anesth Analg. 1990;70:80–5. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zaric D, Axelsson K, Nydahl PA, Philipsson L, Larsson P, Jansson JR. Sensory and motor blockade during epidural analgesia with 1%, 0.75%, and 0.5% ropivacaine – a double-blind study. Anesth Analg. 1991;72:509–15. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199104000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albright GA. Cardiac arrest following regional anesthesia with etidocaine or bupivacaine. Anesthesiology. 1979;51:285–7. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197910000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finucane BT, Sandler AN, McKenna J, Reid D, Milner AL, Friedlander M, et al. A double-blind comparison of ropivacaine 0.5%, 0.75%, 1.0% and bupivacaine 0.5%, injected epidurally, in patients undergoing abdominal hysterectomy. Can J Anaesth. 1996;43:442–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03018104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brockway MS, Bannister J, McClure JH, McKeown D, Wildsmith JA. Comparison of extradural ropivacaine and bupivacaine. Br J Anaesth. 1991;66:31–7. doi: 10.1093/bja/66.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cekmen N, Arslan M, Musdal Y, Babacan A. Comparision of the effects of a single dose of epidural ropivacaine and bupivacaine in arthroscopic operations. Medwell Res J Med Sci. 2008;2:109–15. [Google Scholar]