Abstract

Micropropagation is used for commercial purposes worldwide, but the capacity to undergo somatic organogenesis and plant regeneration varies greatly among species. The plant hormones auxin and cytokinin are critical for plant regeneration in tissue culture, with cytokinin playing an instrumental role in shoot organogenesis. Type-B response regulators govern the transcriptional output in response to cytokinin and are required for plant regeneration. In our paper published in Plant Physiology, we explored the functional redundancy among the 11 type-B Arabidopsis response regulators (ARRs). Interestingly, we discovered that the enhanced expression of one family member, ARR10, induced hypersensitivity to cytokinin in multiple assays, including callus greening and shoot induction of explants. Here we 1) discuss the hormone dependence for in vitro plant regeneration, 2) how manipulation of the cytokinin response has been used to enhance plant regeneration, and 3) the potential of the ARR10 transgene as a tool to increase the regeneration capacity of agriculturally important crop plants. The efficacy of ARR10 for enhancing plant regeneration likely arises from its ability to transcriptionally regulate key cytokinin responsive genes combined with an enhanced protein stability of ARR10 compared with other type-B ARRs. By increasing the capacity of key tissues and cell types to respond to cytokinin, ARR10, or other type-B response regulators with similar properties, could be used as a tool to combat the recalcitrance of some crop species to tissue culture techniques.

Keywords: cytokinin signalling, type-B response regulators, ARABIDOPSIS RESPONSE REGULATOR10 (ARR10), tissue culture, callus induction, de novo shoot organogenesis, plant regeneration

Somatic Organogenesis and Regeneration

Micropropagation is widely used for commercial purposes as a method of vegetative (asexual) propagation from explants derived from shoots, root tips, leaves, cotyledons, anthers, nodes, meristems and/or embryos. The introduction of transgenes into the genome of various plant species may also require subsequent regeneration of viable plantlets from somatic cells.1 Therefore the mechanisms underpinning regenerative potential are important agriculturally. Classic regeneration assays demonstrated that de novo shoot meristem formation requires elevated levels of both auxins and cytokinins, and that these hormones have antagonistic as well as synergistic roles.2 Both are required for cell division and play roles in meristem establishment and activity, but differing cytokinin to auxin ratios favor development of either root or shoot meristems (reviewed by Sugimoto et al.3). In general, increasing the ratio of cytokinin to auxin results in a shift from root to shoot organogenesis.

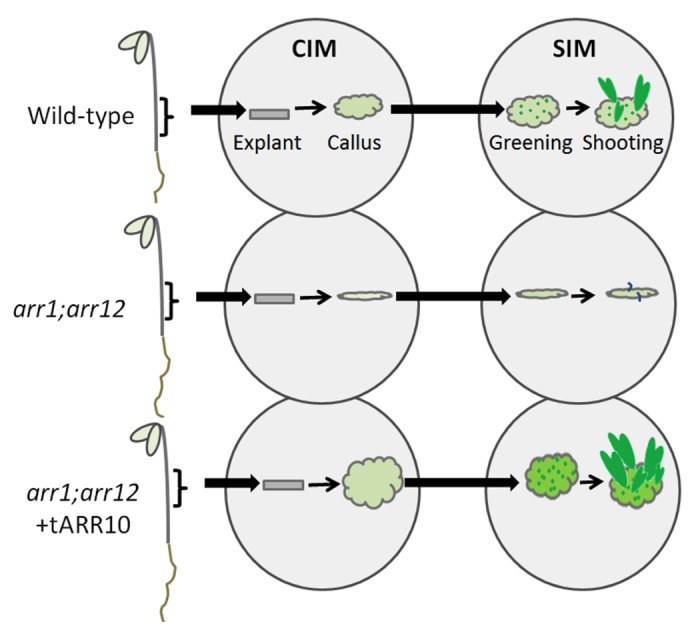

Organ regeneration in plants can be broadly categorised as either direct or indirect (reviewed by Sugimoto et al.4). In the case of the former, shoots or roots are directly induced from tissue explants, whereas indirect organogenesis involves callus formation as an intermediate prior to shoot or root induction. In Arabidopsis, indirect organ regeneration in culture is a two-step process. Small pieces of plant tissue (explants) are first treated with auxin-rich callus-inducing medium (CIM) to form callus, the endogenous levels of cytokinin typically being sufficient for this process. The differentiation state of callus-forming cells has been shown to share many characteristics of the lateral root meristem.5 Subsequent culture of the callus on shoot- or root-inducing medium (SIM or RIM), containing different ratios of auxin to cytokinin, favors the induction of shoot or root tissues, respectively,5 an elevated ratio of cytokinin to auxin favoring shoot formation. In our recent Plant Physiology paper, followed the procedure shown in Figure 1., we found increased callus formation and greening in lines carrying the ARR10 transgene.6

Figure 1. Schematic of callus induction, greening, and shoot formation in Arabidopsis. Hypocotyl segments (explants) are excised from dark grown seedlings and transferred to callus induction media (CIM). Hypocotyl segments are subsequently transferred to shoot induction medium (SIM) to induce greening and shooting. Loss-of-function arr1;arr12 double mutants exhibit reduced callus formation, greening, and shooting compared with wild type. Transgenic expression of ARR10 rescues the arr1;arr12 mutant phenotype and confers increased callus formation, greening, and shooting compared with wild type.6

The capacity for in vitro regeneration varies considerably among plant species. Some families and genera such as the Solanacea (Nicotiana, Petunia and Datura), Cruciferae (Brassica and Arabidopsis), Gesneriaceae (Achimenes and Streptocarpus), Asteraceae (Chichorium and Chrysanthemum) and Liliaceae (Lilium and Allium) can have a high regeneration capacity. In contrast, regeneration in families such as the Malvaceae (Gossypium) and Chenopodiaceae (Beta) is challenging, suggesting that the mechanisms required for in vitro regeneration are insufficient or absent.7 There is even considerable variability in the regenerative potential among different Arabidopsis ecotypes and rice cultivars.8,9 This poses a significant problem for micropropagation and transformation of crop plants.1

Natural differences in the ability to synthesize and respond to cytokinins play a significant role in the capacity for in vitro regeneration. Plants that accumulate higher levels of bioactive cytokinin tend to be more receptive to methods used to induce de novo shoot organogenesis. For example, the Arabidopsis hoc mutant, which accumulates higher levels of endogenous cytokinin, can readily undergo de novo shoot organogenesis, although it also exhibits reduced apical dominance, slower growth of shoots, retarded expansion of leaves, and delayed flowering.10 However, increasing cytokinin levels is irrelevant if tissues are not responsive to the phytohormone. Indeed, attempts to induce organogenesis with endogenous applications of phytohormones have been unsuccessful in a number of species.10 Therefore, increasing the plants ability to respond to cytokinin offers potential advantages over selecting plants that produce higher levels of endogenous cytokinin.

Manipulating the Cytokinin Response to Enhance Regeneration from Tissue Culture

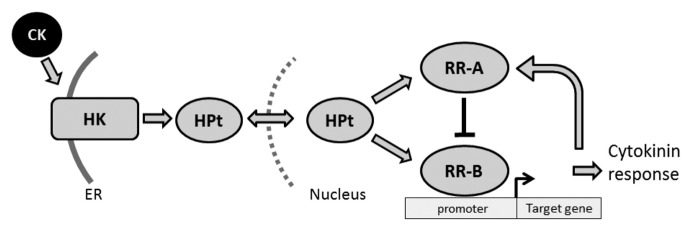

The cytokinin signaling pathway represents a potential target for manipulating de novo shoot organogenesis and in vitro plant regeneration.11 Cytokinin is perceived via a multi-step phosphorelay that involves histidine kinases, histidine-containing phosphotransfer proteins (HPt), and response regulators (reviewed by To and Kieber12). Both dicots and monocots employ a similar mechanism for transducing the cytokinin signal.13,14 Cytokinin binding activates autophosphorylation on a conserved histidine within the kinase domain of the transmembrane histidine-kinase receptor predominantly localized to membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum (Fig. 2). This phosphoryl group is subsequently transferred to the second element in the phosphorelay, the HPt protein, which shuttles back and forth to the nucleus. In the nucleus, the phosphate signal is transferred from the HPt protein to a type-B response regulator. The Type-B response regulators are transcription factors that control the expression of cytokinin-regulated genes. Among the genes whose expression is induced by cytokinin are a second class of response regulators, the type-A response regulators, which function to repress the cytokinin response.15-17

Figure 2. Cytokinin is perceived via a multi-step phosphorelay. Cytokinin (CK) signal transduction occurs by a phosphorelay that incorportates a histidine-kinase receptor (HK), a histidine-containing phospho-transfer protein (HPt), and a type-B response regulator (RR-B). The type-B response regulator activates the transcription of target genes, including type-A response regulators (RR-A), which negatively regulate the pathway.

Loss-of-function mutants in the cytokinin receptors, HPt proteins, and type-B ARRs of Arabidopsis all result in decreased cell division and shooting in tissue culture,15,18-23 suggesting that they could serve as molecular tools by which to manipulate the sensitivity of plants to cytokinin. Based on their role as positive regulators of the cytokinin response, the prediction is that one could increase cytokinin sensitivity by increasing their expression. This prediction has been born out to some extent, with increased expression of the Arabidopsis cytokinin-receptor CRE1 or the type-B response regulators ARR1 or ARR2 resulting in an enhanced response to cytokinin in tissue culture.16,24,25 While promising, these effects of ectopic overexpression on cytokinin sensitivity have been generally more modest than one might wish. In addition, no comparative effort has been undertaken to identify which members of these gene families have the greatest capacity to influence the cytokinin response.

Genetic manipulation of the type-A response regulator levels represents an alternative route to modulating cytokinin sensitivity. The type-A response regulators are negative regulators of the cytokinin response and form part of a negative feedback loop (Fig. 2). Overexpression of the type-A response regulator ARR15 results in reduced cytokinin sensitivity and a reduction in callus greening.26 Therefore, to enhance cytokinin sensitivity one would need to eliminate expression of the type-A response regulators. Consistent with this, loss-of-function mutations within the type-A response regulator family enhance sensitivity. However, several family members need to be repressed to achieve noticeable cytokinin hypersensitivity or enhanced callus induction and shoot regeneration in culture.17,27 This genetic redundancy is a major limitation to using Type-A response regulators to improve regeneration from tissue culture.

Increased expression of several genes that are not integral elements of the primary cytokinin signaling pathway facilitate shoot organogenesis in tissue culture. Ectopic overexpression of the histidine kinase CKI1 alleviates the need for cytokinin to induce shooting in tissue culture, even though CKI1 is not a cytokinin receptor itself, apparently due to its ability to cross-talk with the downstream elements of the cytokinin signaling pathway.28 However, ectopic expression of CKI1 results in sterile plants that are unable to produce roots, limiting its use for micropropagation. The genes ENHANCER OF SHOOT REGENERATION1 (ESR1) and ESR2 enhance shoot regeneration when controlled using an inducible promoter, constitutive expression inducing the formation of dark green calli but inhibiting shoot formation,24,29 ESR1 and ESR2 are transcription factors and characterization of ESR2 suggests that genes involved in cell cycle and meristem activity represent downstream targets, some of these potentially shared with downstream targets of the cytokinin signaling pathway.

ARABIBOPSIS RESPONSE REGULATOR10 (ARR10) Confers Cytokinin Hypersensitivity and Enhanced Callus Formation and Shoot Regeneration In Vitro

In our paper published in Plant Physiology we discovered that changing the expression context of ARR10 results in hypersensitivity to cytokinin and increased sensitivity to cytokinin for plant regeneration.6 For this work, we employed the ARR1 promoter to express all 11 type-B ARRs of Arabidopsis and characterized their ability to rescue the cytokinin-insensitive (hyposensitive) phenotype of an arr1;arr12 mutant. The ARR1 promoter allowed us to express all the type-B ARRs at a similar level, representing an expanded zone of expression for some of the type-B ARRs. We found that the subfamily-1 members ARR1, ARR2, ARR10, and ARR12 and the subfamily-2 member ARR21 restored cytokinin sensitivity to the arr1;arr12 mutant.6 Interestingly, we discovered that ARR10 not only rescued the mutant phenotype but conferred cytokinin hypersensitivity. This hypersensitive effect was observed in multiple assays, including those for plant regeneration in tissue culture. Hypocotyl explants from the transgenic ARR10 lines exhibited greater callus induction, greening, and shooting than wild-type, with all these effects being induced at lower cytokinin concentrations than were necessary in wild-type. We also observed cytokinin hypersensitivity in ARR10 lines driven by the CaMV 35S promoter (unpublished observation), indicating that the hypersensitivity is not dependent on use of the ARR1 promoter. We did not observe a similar hypersensitivity for any of the other transgenic type-B ARR lines, suggesting that ARR10 might prove a particularly useful tool for the molecular modification of cytokinin responses.

Why does ARR10, alone of the type-B ARRs, yield such a substantially enhanced sensitivity based on our analysis? Two characteristics of ARR10 are likely to contribute to this effect. First, ARR10 belongs to the subset of type-B ARRs that contributes the most to the cytokinin response, ARR1, ARR10, and ARR12 having been found to control the majority of the cytokinin responsive gene expression.15,19,20,23 Significantly, we found that the expression of cytokinin primary response genes was stimulated to a substantially higher extent in the transgenic ARR10 lines than in a transgenic ARR1 line, in fact exceeding the expression levels found in the wild-type control.6 Second, the ARR10 protein appears to be more stable than ARR1 and ARR12 proteins; even though the message level for these transgenes was similar, the ARR10 protein accumulated to higher levels.6 Consistent with this hypothesis we found that the ARR10 protein is substantially more stable than ARR1 when we examined its degradation kinetics.6

Two recent studies call attention to the role protein turnover plays in regulating signal output by the type-B ARRs, thereby emphasizing the significance of protein stability in the potential use of cytokinin signaling elements as molecular tools. In the first study, the stability of the type-B response regulator ARR2 was found to decrease in the presence of cytokinin. More stable mutant versions of ARR2 enhanced cytokinin signaling, of particular relevance being the finding that transgenic expression of the stabilized ARR2 exhibited enhanced callus formation in tissue culture compared with wild-type ARR2.25 Interestingly, cytokinin has little effect on the stability of other type-B ARRs, which appear to undergo continuous degradation in either the absence or presence of cytokinin, the kinetics for turnover varying among the type-B ARR family members.25,30 In the second study, a family of F-box proteins (the KISS-ME-DEADLY family; KMD family) was identified that targeted type-B ARRs for degradation, thereby regulating the rate of type-B ARR turnover and their ability to propagate the cytokinin signal.30 Genetic manipulation of KMD levels affected multiple cytokinin-dependent processes, including callus formation and shoot initiation in tissue culture.

Conclusions

Our Plant Physiology paper suggests ARR10 may be a viable candidate for circumventing the recalcitrance of many crop species to tissue culture techniques. Of the 3 key type-B ARRs of Arabidopsis, ARR10 protein is more stable thereby allowing it to propagate a cytokinin signal longer and thus increase the output from the pathway. By increasing the capacity of somatic cells to respond to exogenously supplied cytokinin, we can increase regenerative potential of Arabidopsis. If this research can be translated into crop plants, it offers a potential single gene solution to overcome the recalcitrance of many species to propagation in tissue culture.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation (#IOS-1022053 and #IOS-1238051) and the US Department of Agriculture, Agriculture Food and Research Initiative/National Research Institute (#2007-35304-18323).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Birch RG. Plant transformation: problems and strategies for practical application. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1997;48:297–326. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skoog F, Miller CO. Chemical regulation of growth and organ formation in plant tissues cultured in vitro. Symp Soc Exp Biol. 1957;11:118–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sugimoto K, Gordon SP, Meyerowitz EM. Regeneration in plants and animals: dedifferentiation, transdifferentiation, or just differentiation? Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21:212–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sugimoto K, Meyerowitz EM. Regeneration in Arabidopsis tissue culture. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;959:265–75. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-221-6_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sugimoto K, Jiao Y, Meyerowitz EM. Arabidopsis regeneration from multiple tissues occurs via a root development pathway. Dev Cell. 2010;18:463–71. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hill K, Mathews DE, Kim HJ, Street IH, Wildes SL, Chiang YH, et al. Functional characterization of type-B response regulators in the Arabidopsis cytokinin response. Plant Physiol. 2013;162:212–24. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.208736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mustafa Y. The prerequisite of the success in plant tissue culture: high frequency shoot regeneration. In: Leva A, Rinaldi L (eds). Recent Advances in Plant in vitro Culture 2012:63-90. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Candela M, Velazquez I, De la Cruz R, Sendino AM, De la Pena A. Differences in in vitro plant regeneration ability among four Arabidopsis thaliana ecotypes. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 2001;37:638–43. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khalequzzaman M, Haq N, Hoque M, Aditya T. Regeneration efficiency and genotypic effect of 15 Indica type Bangladeshi rice (Oryza sativa L.) Landraces. Plant Tissue Culture Biotech. 2005;15:33–42. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Catterou M, Dubois F, Smets R, Vaniet S, Kichey T, Van Onckelen H, et al. hoc: An Arabidopsis mutant overproducing cytokinins and expressing high in vitro organogenic capacity. Plant J. 2002;30:273–87. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duclercq J, Sangwan-Norreel B, Catterou M, Sangwan RS. De novo shoot organogenesis: from art to science. Trends Plant Sci. 2011;16:597–606. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.To JP, Kieber JJ. Cytokinin signaling: two-components and more. Trends Plant Sci. 2008;13:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Du L, Jiao F, Chu J, Jin G, Chen M, Wu P. The two-component signal system in rice (Oryza sativa L.): a genome-wide study of cytokinin signal perception and transduction. Genomics. 2007;89:697–707. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsai YC, Weir NR, Hill K, Zhang W, Kim HJ, Shiu SH, et al. Characterization of genes involved in cytokinin signaling and metabolism from rice. Plant Physiol. 2012;158:1666–84. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.192765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Argyros RD, Mathews DE, Chiang YH, Palmer CM, Thibault DM, Etheridge N, et al. Type B response regulators of Arabidopsis play key roles in cytokinin signaling and plant development. Plant Cell. 2008;20:2102–16. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.059584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakai H, Honma T, Aoyama T, Sato S, Kato T, Tabata S, et al. ARR1, a transcription factor for genes immediately responsive to cytokinins. Science. 2001;294:1519–21. doi: 10.1126/science.1065201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.To JP, Haberer G, Ferreira FJ, Deruère J, Mason MG, Schaller GE, et al. Type-A Arabidopsis response regulators are partially redundant negative regulators of cytokinin signaling. Plant Cell. 2004;16:658–71. doi: 10.1105/tpc.018978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hutchison CE, Li J, Argueso C, Gonzalez M, Lee E, Lewis MW, et al. The Arabidopsis histidine phosphotransfer proteins are redundant positive regulators of cytokinin signaling. Plant Cell. 2006;18:3073–87. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.045674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishida K, Yamashino T, Yokoyama A, Mizuno T. Three type-B response regulators, ARR1, ARR10 and ARR12, play essential but redundant roles in cytokinin signal transduction throughout the life cycle of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2008;49:47–57. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcm165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mason MG, Mathews DE, Argyros DA, Maxwell BB, Kieber JJ, Alonso JM, et al. Multiple type-B response regulators mediate cytokinin signal transduction in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2005;17:3007–18. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.035451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishimura C, Ohashi Y, Sato S, Kato T, Tabata S, Ueguchi C. Histidine kinase homologs that act as cytokinin receptors possess overlapping functions in the regulation of shoot and root growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2004;16:1365–77. doi: 10.1105/tpc.021477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riefler M, Novak O, Strnad M, Schmülling T. Arabidopsis cytokinin receptor mutants reveal functions in shoot growth, leaf senescence, seed size, germination, root development, and cytokinin metabolism. Plant Cell. 2006;18:40–54. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.037796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yokoyama A, Yamashino T, Amano Y, Tajima Y, Imamura A, Sakakibara H, et al. Type-B ARR transcription factors, ARR10 and ARR12, are implicated in cytokinin-mediated regulation of protoxylem differentiation in roots of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2006;48:84–96. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcl040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ikeda Y, Banno H, Niu QW, Howell SH, Chua NH. The ENHANCER OF SHOOT REGENERATION 2 gene in Arabidopsis regulates CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON 1 at the transcriptional level and controls cotyledon development. Plant Cell Physiol. 2006;47:1443–56. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcl023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim K, Ryu H, Cho YH, Scacchi E, Sabatini S, Hwang I. Cytokinin-facilitated proteolysis of ARABIDOPSIS RESPONSE REGULATOR 2 attenuates signaling output in two-component circuitry. Plant J. 2012;69:934–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kiba T, Yamada H, Sato S, Kato T, Tabata S, Yamashino T, et al. The type-A response regulator, ARR15, acts as a negative regulator in the cytokinin-mediated signal transduction in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2003;44:868–74. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcg108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buechel S, Leibfried A, To JP, Zhao Z, Andersen SU, Kieber JJ, et al. Role of A-type ARABIDOPSIS RESPONSE REGULATORS in meristem maintenance and regeneration. Eur J Cell Biol. 2010;89:279–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2009.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kakimoto T. CKI1, a histidine kinase homolog implicated in cytokinin signal transduction. Science. 1996;274:982–5. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5289.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Banno H, Ikeda Y, Niu QW, Chua NH. Overexpression of Arabidopsis ESR1 induces initiation of shoot regeneration. Plant Cell. 2001;13:2609–18. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim HJ, Chiang YH, Kieber JJ, Schaller GE. SCFKMD controls cytokinin signaling by regulating the degradation of type-B response regulators. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:10028–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300403110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]