Abstract

The distinctive physicochemical, mechanical and electrical properties of carbon nanostructures are currently gaining the interest of researchers working in bioengineering and biomedical fields. Carbon nanotubes, carbon dendrimers, graphenic platelets and nanodiamonds are deeply studied aiming at their application in several areas of biology and medicine.

Here we provide a summary of the carbon nanomaterials prepared in our labs and of the fabrication techniques used to produce several biomedical utilities, from scaffolds for tissue growth to cargos for drug delivery and to biosensors.

Keywords: carbon nanostructures, bio-nanomaterials, scaffolds, nanomedicine

Introduction

The discipline of synthetic biomedical materials for nanomedicine has evolved quite rapidly in the last years, and materials/components with suitable physical-chemical-mechanical properties combined with specifically designed surfaces radically changed the device industry and the main aspects of clinical care.1

Current biomaterials research is offering promising alternatives to conventional medical devices, and functional systems engineered at the nanoscale are opening completely new routes to imaging/labeling, drug delivery, fabrication of artificial organs as well as of prosthetics and packaging systems.2 However, for biomedical applications, composition and structure of the surfaces and in particular of the bio-interfaces must meet strict requirements in terms of biocompatibility and long-time reliability. Recent studies demonstrated that, among the inorganic materials used in nanomedicine, the sp2 and sp3 hybridized nanocarbons have the primacy3.

The engineering of nanocarbon surfaces for bio-related applications is nowadays an emerging and rapidly developing research field, due to the outstanding properties of the carbon nanostructures and to the applications envisioned for platforms and multivalent architectures based on them.

In particular, the diamond surface is characterized by chemical inertness, full bio-compatibility and ultra-hardness. The nanodiamond surfaces can be terminated with H, O or OH-, and further versatility can be given by secondary functionalizations, that open the way to conjugations with a series of more complex entities, going from proteins to carbohydrates or nucleic acids.15

In our labs a series of strategies have been explored for the preparation of surfaces assembled with nanodiamonds, graphite nanoplatelets, carbon nanotubes, helical and dendrimeric nanostructures. These nanostructured surfaces are proposed for a series of different applications, from drug delivery platforms to bioimplants, from scaffold for tissue-growth to site-specific molecular targeting and labeling.

This paper describes some chemical-physical approaches for the preparation of functional interfaces based on carbon nanotubes, carbon helical and dendrimeric nanostructures, graphenic platelets and nanodiamonds.

Materials Preparation and Characterization

Carbon Nanotubes, dendrimers and helical nanostructures

The synthetis strategies for the fabrication of specifically shaped surfaces assembled with single-walled nanotubes (SWCNT), dendrimers and helical structures rely on the use of purpose-designed Hot-Filament CVD apparatus.4

The growth of these sp2-coordinated carbon forms is obtained using carbon-containing feeding gases and atomic H. The carbon reagents are CH4 or amorphous carbon powders transported by inert gas fluxes. Typically CH4/H2 mixtures (at a flowing rate of about 200 sccm, with CH4 in the range 1–4%) or C-containing gaseous phases are delivered to the active area of the reactor, where a Ta filament activates the reactants and produces atomic hydrogen. The main conditions of the CVD synthesis are: filament temperature: 2200 ± 10 °C, substrate temperature: 600–800 °C, total pressure: 20–40 Torr. Depending on the preparation of the substrate, continuous deposits of SWCNT or bundles growths on selected areas can be produced. Moreover the growth can be modulated in order to obtain arrays of vertically aligned tubular nanostructures or entangled mats horizontally placed on the substrates. Dendrimers and helical nanostructures are obtained using carbon powders containing traces (ppm) of S.

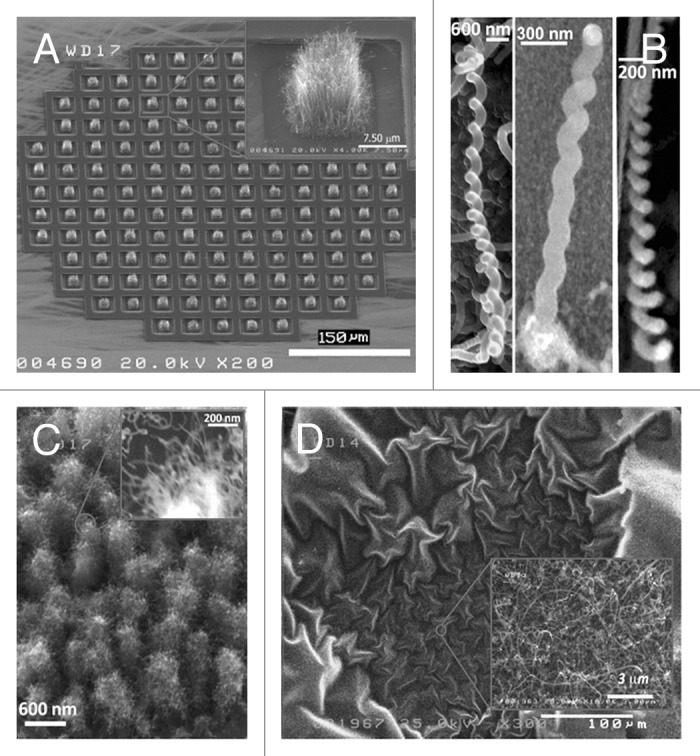

Some examples of surfaces modified by carbon nanotubes, helical and dendrimeric structures are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. SEM images of: (A) deposits of vertically aligned SWCNT grown on selected areas of a patterned substrate; (B) helical carbon nanostructures; (C) carbon dendrimers; and (D) large area deposit of entangled SWCNT mats horizontally placed on a substrate.

Graphenic platelets

Graphenic nanoplatelets are obtained from disruption of SWCNT by using high-shear mixing and/or treatments in sulfonitric mixtures (60% HNO3, 95% H2SO4 in a 1:3 volume ratio) either at room or high temperatures (90 °C).

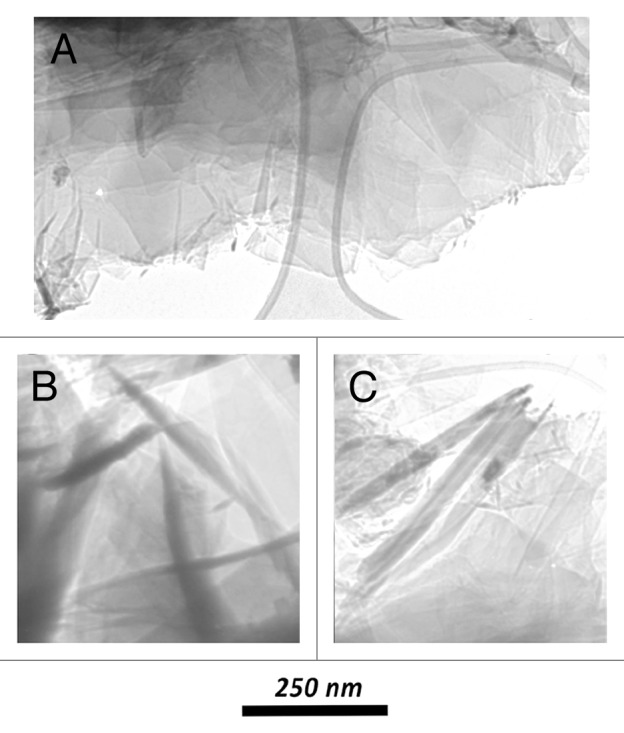

The adopted unzipping methodologies produces in each case graphitic flakes, having no long-range translational or orientational order, and, depending on the different procedures, we already reported5 experimental evidence of different kinds of re-organization. The complementary use of electron diffraction and microscopy techniques evidence indeed very different interactions between proximal units in samples obtained by different disruption processes. In particular, it is possible to produce turbostratic arrangements of graphene planes with their perpendicular c-axis not perfectly oriented along the same direction, nanomosaic arrangements of self-assembled flakes into an hexagonal graphite structure with P63/mcc symmetry, or randomly oriented graphitic platelets with smooth surfaces.5 Overall, the choice of specific disruption treatments and of suitable dispersion medium makes it possible to selectively produce different assembling of graphene layers and obtain carbon platelets with pre-defined forms. In Figure 2 some typical assembling is reported. The use of these interesting graphenic materials is being proposed for various biomedical applications, from drug delivery to biosensing.6

Figure 2. SEM images of: (A) overlapped platelets in a plane perpendicular to the e-beam; (B and C) some isolated/individual platelets with the e-beam near-parallel to their surfaces.

Nanodiamonds

The nanodiamonds used for surface modifications are produced by two different routes.

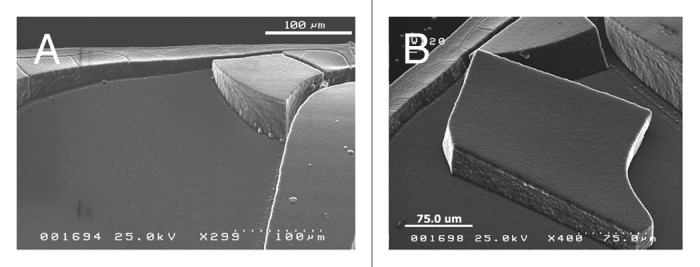

The first one makes use of nanodiamond commercial powders generated by detonation of carbon precursors in an inert medium. The structure of a single “detonation nanodiamond” (DN) crystallite consists of a sp3-coordinated C core surrounded by a thin graphitic shell.7 The sizes of the polyhedral grains are in the range 4–10 nm. Nanodiamonds are characterized by a complex surface chemistry and by a facet-dependent surface potential, that are responsible of strong interactions occurring between the crystallites, and that give rise to tight aggregates with large size (hundreds microns). The re-dispersion of DN into single particles is a challenging task, that needs the settling of specific chemical-physical protocols to avoid re-aggregation of the primary nanoparticles.8,9 In our labs stable colloidal dispersions of DN are obtained by mechanical treatments and chemical functionalizations. A proper setting of solvent and drying methods enables to produce all-nanodiamond solid structures with predefined architectures10.Some examples of DN shaped deposits are reported in Figure 3.

Figure 3. (A and B) SEM images of all-diamond solid structures produced with nanodiamond particles.

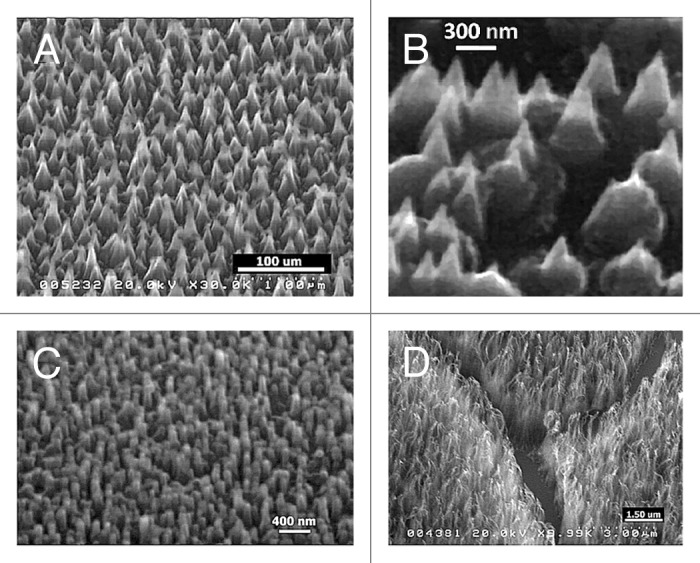

As regards the second route, we have devised schemes for creating nanometer-scale 3D structures (nanorods, nanowhiskers, nanopillars, nanocones) by the sculpturing of plane diamond films. The poly- or nano-crystalline diamond films are produced by HF- CVD, following previously settled methodologies.11,12 The nanometric control of materials morphology is obtained by means of a controlled temperature H etching (from room temperature to 1000 °C),13 using a custom-made dual-mode MW-RF plasma reactor. In Figure 4 are shown some examples of nanostructures obtained by H-etching processes applied to previously produced diamond films or occurring during the diamond synthesis performed using the MW-RF CVD reactor.14

Figure 4. SEM images of diamond (A and B) nanocones, (C) nanopillars and (D) nanowhiskers produced by the sculpturing of plane diamond films by means of MW-RF CVD plasma reactor.

Discussion and Conclusions

A variety of different strategies can be used for the preparation of specifically shaped and/or terminated surfaces enabling nanocarbon-based bioapplications. Both sp2 and sp3 nanocarbons can selectively bind various biological molecules and represent new classes of bioactive delivery vehicles.

As regards the graphitic nanocarbons, this class couples a good biocompatibility with outstanding mechanical and charge transport properties, that make them very well qualified for a series of bio-analytical applications. Moreover these materials can be easily stacked to fabricate low-cost, large-area membranes with controlled porosity.

Carbon nanotubes, helical structures, dendrimers and graphite nanoplatelets with various size, shape and specific surface functionality imparted by tailored attachment schemes, are therefore proposed as sensing elements and reinforcing agents for bio-devices, as well as tools for separating and purifying biological systems.

In this context, nanodiamond is proposed for selective attachment of targeting groups and for controlled administration of therapeutic agents. Nanodiamond particles have suitable properties to be linked to functional groups and complex molecules by pure Van der Waals interactions, but also by chemical bonds of different nature, such as covalent or electrostatic bonding.

It has been also probed that nanodiamond is an excellent substrate for the adhesion and growth of several types of cells in vitro. DN-shaped surfaces are presently considered attractive scaffolds for tissue growth, and good candidates for bio-implants, whereas nanodiamond elongated structures (nanorods, nanowhiskers, nanopillars, nanocones) with well defined arrangement of molecules on the tips are proposed as drug delivery cargos.

Overall, nanodiamond opened new scenarios in the design of systems for biomedical applications: it can be used to image or label biomolecules and to assist in drug delivery, making possible to define new reliable and effective strategies for theranostic approaches.

An interdisciplinary methodology and the collaboration of researchers from bio-related areas are needed in order to implement the above reported research topics and to translate these modified carbon nanostructures into potential smart medical materials.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Singh SK, Kulkarni PP, Dash D. Biomedical applications of nanomaterials: an overview, in Bio-Nanotechnology: A Revolution in Food, Biomedical and Health Sciences (Bagchi D, Bagchi M, Moriyama H, Shahidi F, editor). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.; 2013. 856p. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhat S, Kumar A. Biomaterials and bioengineering tomorrow’s healthcare. Biomatter. 2013;3:e24717. doi: 10.4161/biom.24717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamashita T, Yamashita K, Nabeshi H, Yoshikawa T, Yoshioka Y, Tsunoda S, Tsutsumi Y. Carbon Nanomaterials: Efficacy and Safety for Nanomedicine. Materials. 2012;5:350–63. doi: 10.3390/ma5020350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guglielmotti V, Orlanducci S, Tamburri E, Cianchetta I, Gay S, Lavecchia T, Reina G, Passeri D, Rossi M, Terranova ML. CVD-based techniques for the synthesis of nanographites and nanodiamonds. Nuovo Cim. 2013;36C:3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matassa R, Orlanducci S, Tamburri E, Guglielmotti V, Sordi D, Terranova ML, Rossi M. Characterization of carbon structures produced by graphene self-assembly. J Appl Cryst. 2014;47:222–7. doi: 10.1107/S1600576713029488. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feng L, Liu Z. Graphene in biomedicine: opportunities and challenges. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2011;6:317–24. doi: 10.2217/nnm.10.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mochalin VN, Shenderova O, Ho D, Gogotsi Y. The properties and applications of nanodiamonds. Nat Nanotechnol. 2012;7:11–23. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aleksenskiy AE, Eydelman ED, Vul’ AY. Deagglomeration of Detonation Nanodiamonds. Nanosci Nanotechno Lett. 2011;3:68–74. doi: 10.1166/nnl.2011.1122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Panich AM, Aleksenskii AE. Deaggregation of diamond nanoparticles studied by NMR. Diamond Related Materials. 2012;27–28:45–8. doi: 10.1016/j.diamond.2012.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terranova ML, Orlanducci S, Tamburri E, Guglielmotti V, Toschi F, Hampai D, Rossi M. Polycrystalline diamond on self-assembled detonation nanodiamond: a viable route for fabrication of all-diamond preformed microcomponents. Nanotechnology. 2008;19:415601. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/19/41/415601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orlanducci S, Fiori A, Sessa V, Tamburri E, Toschi F, Terranova ML. Nanocrystalline diamond films grown in nitrogen rich atmosphere: structural and field emission properties. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2008;8:3228–34. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2008.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orlanducci S, Guglielmotti V, Cianchetta I, Lucci M, Toschi F, Tamburri E, Terranova ML. Diamond layers grown by chemical vapor deposition on NbN systems and NbN/SiO2-based devices. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2011;11:8185–9. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2011.5095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orlanducci S, Guglielmotti V, Sessa V, Tamburri E, Terranova ML, Toschi F, Rossi M. Shaping of Diamonds in 1D Nanostructures and Strategies for Fabrication of All-Diamond Microcomponents. Mater Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. 2012; 1395: 93-98. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orlanducci S, Guglielmotti V, Cianchetta I, Sessa V, Tamburri E, Toschi F, Terranova ML, Rossi M. One-step growth and shaping by a dual-plasma reactor of diamond nanocones arrays for the assembling of stable cold cathodes. Nanosci Nanotechno Lett. 2012;4:338–43. doi: 10.1166/nnl.2012.1312. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dean Ho, ed. Nanodiamonds: applications in biology and nanoscale medicine. New York: Springer; 2010. 288p. [Google Scholar]