Abstract

Components of the vesicle trafficking machinery are central to the immune response in plants. The role of vesicle trafficking during pre-invasive penetration resistance has been well documented. However, emerging evidence also implicates vesicle trafficking in early immune signaling. Here we report that Exo70B1, a subunit of the exocyst complex which mediates early tethering during exocytosis is involved in resistance. We show that exo70B1 mutants display pathogen-specific immuno-compromised phenotypes. We also show that exo70B1 mutants display lesion-mimic cell death, which in combination with the reduced responsiveness to pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) results in complex immunity-related phenotypes.

Keywords: cell death, lesion mimic, basal resistance, nonhost resistance, vesicle trafficking, biotroph, hemibiotroph

Introduction

The perception of pathogens by plasma membrane located pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) activates a wide range of host responses. At the core of these responses is the vesicle trafficking between the endomembrane system, which is required for processes ranging from the regulation of early signaling to the deployment of immune responses at later stages.

The importance of vesicle trafficking in plants was first recognized in the interaction with pathogens that penetrated the cell wall, such as biotrophic powdery mildew fungi.1 A highly focal response is deployed under the site of attempted penetration which results in the formation of cell wall appositions and the local secretion of defense-related compounds.2

These responses are dependent on various components that include a ternary soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive-factor attachment receptor (SNARE) complex that consists of SYP121 (PEN1), SNAP33, and VAMP721/722.3,4 It also involves the polarization of the cytoskeleton, including actin and tubulin.5,6

However, recent data indicate that vesicle trafficking is also required at early stages of infection, and its roles include the downregulation of signaling mediated by PRRs such as FLS2, the receptor of bacterial flagellin.7-10 Binding of the flg22 peptide of flagellin to FLS2 leads to the activation of the intracellular kinase domain and down-stream signaling cascades. The activated FLS2 was shown to be endocytosed within 30 min after activation and degraded at later time points.7,11 Further elucidation of the trafficking route showed that FLS2 receptors constitutively recycle in a Brefeldin A (BFA)-sensitive manner. Moreover, activated FLS2 traffics via ARA7/Rab F2b- and ARA6/Rab F1-positive endosomes.12

Ubiquitination has been shown to play key functions in the regulation of vesicle trafficking.13,14 The triplet of sequence-related ligases PUB22, PUB23, and PUB24, which negatively regulates immunity,15 was shown to interact with Exo70B2, a subunit of the exocyst and the closest homolog of Exo70B1.16 PUB22 ubiquitinates Exo70B2 in vitro. The degradation of Exo70B2 after activation of immunity was dependent on the PUB triplet. Loss-of-function mutants of exo70B2 and its closest homolog exo70B1 were compromised in early receptor-mediated signaling. Furthermore, exo70B2 plants were more susceptible to Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis (Hpa) isolate Emco5 and Pseudomonas syringae pv tomato DC3000 (Pst).16 Exo70H1, a homolog of Exo70B2, was also shown to be involved in the immune response.17 Furthermore, homologs of the Exo70 subunit and another tethering complex termed conserved oligomeric Golgi complex (COG), Exo70F-like, and COG3 respectively, are required for the penetration resistance of barley against the Blumeria graminis f.sp. hordei fungus.18

A recent study by Kulich and colleagues showed that Exo70B1 could contribute to autophagy.19 Plants displaying extended cell death lesions also hyper-accumulated SA. The SA-pathway contributed to cell death as lesion mimic was suppressed in the exo70b1–2/npr1 double mutant.

The exocyst is an octameric complex that mediates early steps of exocytosis before SNARE-mediated membrane fusion.20 In plants, exocyst function has also been linked to polar secretion required for growth and pollen incompatibility.21,22 Exo70 is thought to interact with the target membrane through a phosphoinositide-binding domain, and thus act as a landmark to guide tethering and exocytosis.23 Although the exocyst is an evolutionarily conserved complex, the Exo70 gene family in plants has greatly expanded. Whereas most metazoans possess only one Exo70 gene, Arabidopsis has 23 homologs, and rice (Oryza sativa) contains at least 32.24 This expansion suggests that plants have evolved functionally specialized Exo70 genes.22

In this short communication we tested the interaction between exo70B1 mutants and pathogens with different life-styles. We report that Exo70B1, which is the closest homolog of Exo70B2, contributes to resistance and also to cell death.

Results

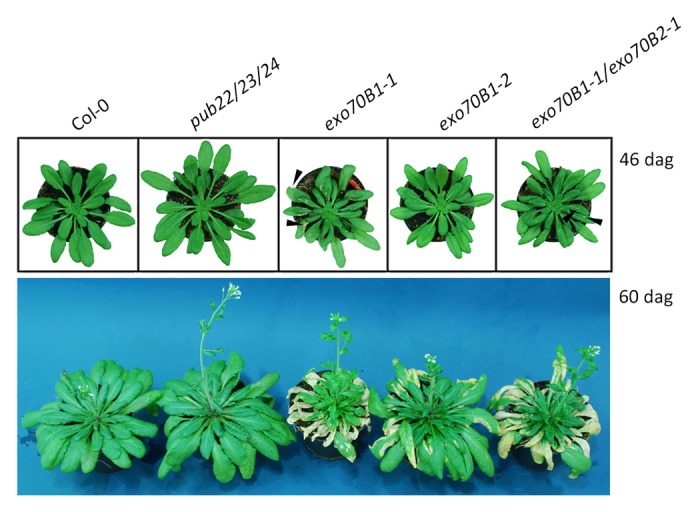

To analyze the function of Exo70B1 in immunity we used 2 independent T-DNA insertion alleles, exo70B1–1 (GK114C03) and exo70B1–2 (GK156G02), both in Col-0 background.16 We first characterized their development using short day conditions (8h light/16h dark). Plant growth was generally comparable to wild type up to approximately 40–46 d after germination. At this time point exo70B1–1 plants started displaying small cell death lesions (Fig. 1). Lesions increased with time and consumed older leaves completely in exo70B1–1 by the time plants were flowering. We also observed that mechanical stress caused by late transfer of seedlings into pots, over-watering or low light exacerbated lesion formation (not shown).

Figure 1. Loss-of-function exo70B1 mutants display lesion mimic cell death. Plants were sown on soil, stratified for 3 days at 4°C and grown under short day conditions (8h light/16h dark) at 21°C and 70% humidity. Shown are plants 46 and 60 d after germination (dag).

The penetrance of the cell death phenotype was clearly weaker in the exo70B1–2 allele, which displayed smaller lesions that appeared later than in exo70B1–1. The exo70B1–1/exo70B2–1 double mutant displayed lesion mimic development that was similar to the exo70B1–1 single mutant. This suggests that although Exo70B1 and Exo70B2 share 53.3% amino acid sequence identity, they do not functionally overlap. Moreover, Exo70B2 is not genetically necessary for the exo70B1 lesion mimic phenotype.

Lesion formation was partially suppressed when plants were grown under long day (16h light/8h dark), as previously reported.19 However, exo70B1–1 still showed larger lesions in comparison to exo70B1–2 (data not shown). Nevertheless, in both cases lesion mimic appeared 5–10 d before bolting, suggesting a connection to flowering.

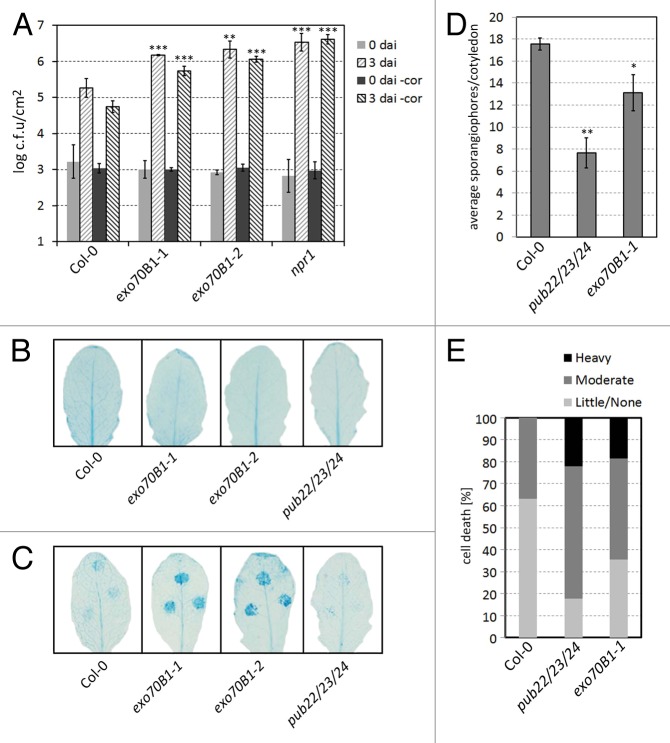

To test whether Exo70B1 plays a role in the immune response, we first assayed the interaction of mutant plants with a virulent hemibiotrophic pathogen. For this purpose we used Pst and a mutant which is unable to produce coronatine, a virulence factor (Pst -cor).25 Due to the severity of the disease symptoms on exo70B1 plants, samples were harvested 3 d after inoculation (dai). At this time point, exo70B1 mutants displayed wide spread chlorosis and confluent cell death, which was markedly stronger compared with Col-0 wild type. The clear disease phenotype was reflected by the significant increase in bacterial multiplication in both exo70B1 mutant alleles (Fig. 2A). As a susceptible control we used npr1, which displayed a bacterial growth that was comparable to exo70B1–2. Infection phenotypes were comparable but more pronounced in the mutants when plants were inoculated with the less virulent Pst -cor (Fig. 2A). Plants used for pathogen infection assays were 5- to 6-week-old, most of which did not display cell death lesions (approx. 90%, Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Resistance phenotypes of loss-of-function exo70B1 mutants. (A) Infection assays with the virulent bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv tomato DC3000 (Pst) and coronatine deficient Pst -cor mutants. Col-0, exo70B1–1, exo70B1–2, and npr1 plants were spray inoculated with a bacterial suspension of 5x108 cfu/mL. Infection and bacterial growth were assessed at 0 and 3 d after inoculation (dai). Data shown as mean 6 SD (n = 5). Similar results were obtained in 3 independent experiments. Statistical significance between wild-type Col-0 and mutant lines was assessed with the Student t test (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). (B) Leaves used for pathogen infection assays did not display cell death. Six-week-old leaves were stained with trypan blue to detect cell death. Shown are pictures of representative leaves. (C) Localized cell death response phenotype of mutants lines. Leaves were inoculated with P. infestans (1x105 spores/mL) and stained with trypan blue at 3dai. Shown results are representative of 3 independent experiments. (D) Infection assay with the oomycete pathogen Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis isolate Emco5 (Hpa). Two-week-old seedlings were inoculated with a solution of 5x104 spores/mL. Hpa growth was assessed by counting the number of sporangiophores 7 dai +/− SE, on at least 50 cotyledons. Experiments were repeated 5 times with similar results. (E) Emco5-infected cotyledons were stained with trypan blue and cell death lesions were scored as none/small, moderate, or large. Shown are the percentages for average of each category of cell death from 3 independent experiments.

We next tested the role of Exo70B1 in nonhost resistance against the oomycete Phytophthora infestans (Pi). Pi is the causal agent of the late blight disease of potato. During the onset of infection it shows a short biotrophic phase and switches at later stages to a necrotrophic life-style. In Arabidopsis, immunity to Pi is dependent on both a pre-invasive penetration resistance and post-invasive responses such as the hypersensitive reaction (HR).

Five- to 6-week-old plants were drop-inoculated with a suspension of 1x105 spores/mL and harvested 3 dai. We stained leaves with trypan blue to detect cell death response. As previously shown, Col-0 plants displayed minimal levels of cell death.26 The pub22/pub23/pub24 triple mutant displayed cell death levels comparable to WT Col-0 (Fig. 2C). However, both alleles of exo70B1 showed a marked increase in cell death, which was primarily observed in the mesophyll tissue. The increased cell death indicates that the immune response of exo70B1 mutants toward Pi is altered. Pi penetration is expected to trigger the cell death response as it is a nonhost. However, altered penetration rates resulting in epidermal cell death could not be reliably quantified at this time point of infection.

Lastly, we tested the impact of exo70B1 mutation in the interaction with the strictly biotrophic Hpa isolate Emco5. The pub22/pub23/pub24 triple mutant showed enhanced resistance against Hpa when compared with Col-0, as reported previously.15 Surprisingly, exo70B1–1 was also more resistant to infection with Hpa (Fig. 2D). Our prior studies using mutants of Exo70B2, its closest homolog, showed that these were more susceptible to Hpa. The enhanced resistance to Hpa was also surprising because exo70B1 mutants are compromised in PAMP-triggered responses.16 To investigate the possible reason for the enhanced resistance, we assayed the levels of cell death by staining infected leafs with trypan blue. Indeed, we were able to observe an increase in cell death which was comparable to that of the pub triple mutant which could account for the increased resistance against Hpa (Fig. 2D and 2E).

Discussion

Our data shows that mutation of Exo70B1 results in a complex combination of immunity-linked phenotypes. We previously showed that exo70B1 mutants were compromised in early responses to PAMPs, which is likely due to impaired PRR signaling.16 This observation is also in line with the increased susceptibility against virulent Pst and Pst -cor (Fig. 2A). Of note, the severity of exo70B1 disease symptoms from Pst infection, including confluent cell death, could also be the result of a reduced threshold to activate cell death. This is also consistent with the observed lesion mimic in uninoculated plants older than 6 weeks. It is important to bear in mind that Pst is a hemibiotrophic pathogen, which might allow it to escape necrosis type cell death. Crucial factors deciding the balance between resistance and susceptibility in this case could be the type of cell death, necrosis vs. programmed cell death, and the timing of cell death onset.

Similarly to the interaction phenotype observed for Pst on exo70B1 plants, a reduced threshold could result in the enhanced cell death during the interaction with the nonhost Pi. However, it is worth noting that for certain penetrating nonhost pathogens, such as powdery mildews, the breaching of the cell wall appears to be the cell death trigger.27-29 The enhanced cell death displayed by exo70B1 mutants inoculated with Pi was reminiscent of the phenotype described for pen2.26 PEN2 is a peroxisome-associated myrosinase that metabolizes the indole glucosinolate, 4-methoxyindol-3-ylmethylglucosinolate, and releases tryptophan-derived antimicrobial metabolites proposed to be exported in a PEN3 dependent manner.30,31 The observed phenotype suggests that exo70B1 mutants could be compromised in pre-invasive penetration resistance resulting in enhanced cell death, analogously to pen2 plants. Increased penetration in exo70B1 can be the result of their compromised immune signaling as previously shown.16 This does not exclude the possibility that Exo70B1 also participates in the formation of cell wall appositions.

Arabidopsis Col-0 seedlings are susceptible to Hpa Emco5, and we observed an increased resistance accompanied by more cell death in exo70B1 (Fig. 2E). This was surprising as exo70B1 was impaired in PAMP-triggered responses and more susceptible to Pst. However, Hpa is a strict biotroph and cannot escape cell death as in the case of Pst. In contrast to the interaction with Pst, a reduced cell death activation threshold would invariably result in enhanced resistance against Hpa. In support of a reduced cell death threshold, a recent report indicated that exo70B1 is involved in autophagy-related transport to the vacuole.19 Autophagy was shown to play both negative and positive roles in immunity and cell death.32,33 Importantly, SA-dependent phenotypes were mostly observed in older plants. By contrast, results obtained from seedlings or plants not displaying senescence or cell death were SA-independent.34

Our results show that Exo70B1 plays a role in the defense response against various pathogens which trigger immune responses tailored to their life-style. Loss-of-function exo70B1 mutants displayed different pathogen-specific phenotypes. Future studies will determine whether reduced PAMP-signaling and lesion mimic displayed by exo70B1 mutants are linked or whether they are the result of its function in different cellular processes.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft SFB 567 (Stegmann M and Trujillo M), Leibniz Gemeinschaft (Trujillo M), National Science Foundation, Integrative and Organismal Biology Award 0744875 (Anderson RG and McDowell JM).

References

- 1.Bednarek P, Kwon C, Schulze-Lefert P. Not a peripheral issue: secretion in plant-microbe interactions. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2010;13:378–87. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collins NC, Thordal-Christensen H, Lipka V, Bau S, Kombrink E, Qiu JL, Hückelhoven R, Stein M, Freialdenhoven A, Somerville SC, et al. SNARE-protein-mediated disease resistance at the plant cell wall. Nature. 2003;425:973–7. doi: 10.1038/nature02076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ali GS, Prasad KV, Day I, Reddy AS. Ligand-dependent reduction in the membrane mobility of FLAGELLIN SENSITIVE2, an arabidopsis receptor-like kinase. Plant Cell Physiol. 2007;48:1601–11. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcm132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kwon C, Neu C, Pajonk S, Yun HS, Lipka U, Humphry M, Bau S, Straus M, Kwaaitaal M, Rampelt H, et al. Co-option of a default secretory pathway for plant immune responses. Nature. 2008;451:835–40. doi: 10.1038/nature06545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoefle C, Huesmann C, Schultheiss H, Börnke F, Hensel G, Kumlehn J, Hückelhoven R. A barley ROP GTPase ACTIVATING PROTEIN associates with microtubules and regulates entry of the barley powdery mildew fungus into leaf epidermal cells. Plant Cell. 2011;23:2422–39. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.082131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Opalski KS, Schultheiss H, Kogel KH, Hückelhoven R. The receptor-like MLO protein and the RAC/ROP family G-protein RACB modulate actin reorganization in barley attacked by the biotrophic powdery mildew fungus Blumeria graminis f.sp. hordei. Plant J. 2005;41:291–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robatzek S, Chinchilla D, Boller T. Ligand-induced endocytosis of the pattern recognition receptor FLS2 in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2006;20:537–42. doi: 10.1101/gad.366506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chinchilla D, Bauer Z, Regenass M, Boller T, Felix G. The Arabidopsis receptor kinase FLS2 binds flg22 and determines the specificity of flagellin perception. Plant Cell. 2006;18:465–76. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.036574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu D, Lin W, Gao X, Wu S, Cheng C, Avila J, Heese A, Devarenne TP, He P, Shan L. Direct ubiquitination of pattern recognition receptor FLS2 attenuates plant innate immunity. Science. 2011;332:1439–42. doi: 10.1126/science.1204903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith JM, Salamango DJ, Leslie ME, Collins CA, Heese A. Sensitivity to flg22 is modulated by ligand-induced degradation and de novo synthesis of the endogenous flagellin-receptor FLS2. Plant Physiol. 2013 doi: 10.1104/pp.113.229179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Göhre V, Spallek T, Häweker H, Mersmann S, Mentzel T, Boller T, de Torres M, Mansfield JW, Robatzek S. Plant pattern-recognition receptor FLS2 is directed for degradation by the bacterial ubiquitin ligase AvrPtoB. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1824–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beck M, Zhou J, Faulkner C, MacLean D, Robatzek S. Spatio-temporal cellular dynamics of the Arabidopsis flagellin receptor reveal activation status-dependent endosomal sorting. Plant Cell. 2012;24:4205–19. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.100263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Furlan G, Klinkenberg J, Trujillo M. Regulation of plant immune receptors by ubiquitination. Front Plant Sci. 2012;3:238. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2012.00238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacGurn JA, Hsu PC, Emr SD. Ubiquitin and membrane protein turnover: from cradle to grave. Annu Rev Biochem. 2012;81:231–59. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060210-093619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trujillo M, Ichimura K, Casais C, Shirasu K. Negative regulation of PAMP-triggered immunity by an E3 ubiquitin ligase triplet in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1396–401. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stegmann M, Anderson RG, Ichimura K, Pecenkova T, Reuter P, Žársky V, McDowell JM, Shirasu K, Trujillo M. The ubiquitin ligase PUB22 targets a subunit of the exocyst complex required for PAMP-triggered responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2012;24:4703–16. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.104463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pecenková T, Hála M, Kulich I, Kocourková D, Drdová E, Fendrych M, Toupalová H, Zársky V. The role for the exocyst complex subunits Exo70B2 and Exo70H1 in the plant-pathogen interaction. J Exp Bot. 2011;62:2107–16. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ostertag M, Stammler J, Douchkov D, Eichmann R, Hückelhoven R. The conserved oligomeric Golgi complex is involved in penetration resistance of barley to the barley powdery mildew fungus. Mol Plant Pathol. 2013;14:230–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2012.00846.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kulich I, Pečenková T, Sekereš J, Smetana O, Fendrych M, Foissner I, Höftberger M, Zárský V. Arabidopsis exocyst subcomplex containing subunit EXO70B1 is involved in autophagy-related transport to the vacuole. Traffic. 2013;14:1155–65. doi: 10.1111/tra.12101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heider MR, Munson M. Exorcising the exocyst complex. Traffic. 2012;13:898–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2012.01353.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Samuel MA, Chong YT, Haasen KE, Aldea-Brydges MG, Stone SL, Goring DR. Cellular pathways regulating responses to compatible and self-incompatible pollen in Brassica and Arabidopsis stigmas intersect at Exo70A1, a putative component of the exocyst complex. Plant Cell. 2009;21:2655–71. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.069740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zárský V, Cvrcková F, Potocký M, Hála M. Exocytosis and cell polarity in plants - exocyst and recycling domains. New Phytol. 2009;183:255–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.He B, Xi F, Zhang X, Zhang J, Guo W. Exo70 interacts with phospholipids and mediates the targeting of the exocyst to the plasma membrane. EMBO J. 2007;26:4053–65. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cvrčková F, Grunt M, Bezvoda R, Hála M, Kulich I, Rawat A, Zárský V. Evolution of the land plant exocyst complexes. Front Plant Sci. 2012;3:159. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2012.00159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brooks DM, Hernández-Guzmán G, Kloek AP, Alarcón-Chaidez F, Sreedharan A, Rangaswamy V, Peñaloza-Vázquez A, Bender CL, Kunkel BN. Identification and characterization of a well-defined series of coronatine biosynthetic mutants of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2004;17:162–74. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2004.17.2.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kopischke M, Westphal L, Schneeberger K, Clark R, Ossowski S, Wewer V, Fuchs R, Landtag J, Hause G, Dörmann P, et al. Impaired sterol ester synthesis alters the response of Arabidopsis thaliana to Phytophthora infestans. Plant J. 2013;73:456–68. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trujillo M, Kogel K-H, Hückelhoven R. Superoxide and hydrogen peroxide play different roles in the nonhost interaction of barley and wheat with inappropriate formae speciales of Blumeria graminis. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2004;17:304–12. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2004.17.3.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacobs AK, Lipka V, Burton RA, Panstruga R, Strizhov N, Schulze-Lefert P, Fincher GB. An Arabidopsis Callose Synthase, GSL5, Is Required for Wound and Papillary Callose Formation. Plant Cell. 2003;15:2503–13. doi: 10.1105/tpc.016097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nishimura MT, Stein M, Hou BH, Vogel JP, Edwards H, Somerville SC. Loss of a callose synthase results in salicylic acid-dependent disease resistance. Science. 2003;301:969–72. doi: 10.1126/science.1086716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bednarek P, Pislewska-Bednarek M, Svatos A, Schneider B, Doubsky J, Mansurova M, Humphry M, Consonni C, Panstruga R, Sanchez-Vallet A, et al. A glucosinolate metabolism pathway in living plant cells mediates broad-spectrum antifungal defense. Science. 2009;323:101–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1163732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lipka V, Dittgen J, Bednarek P, Bhat R, Wiermer M, Stein M, Landtag J, Brandt W, Rosahl S, Scheel D, et al. Pre- and postinvasion defenses both contribute to nonhost resistance in Arabidopsis. Science. 2005;310:1180–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1119409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hofius D, Schultz-Larsen T, Joensen J, Tsitsigiannis DI, Petersen NH, Mattsson O, Jørgensen LB, Jones JD, Mundy J, Petersen M. Autophagic components contribute to hypersensitive cell death in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2009;137:773–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoshimoto K, Jikumaru Y, Kamiya Y, Kusano M, Consonni C, Panstruga R, Ohsumi Y, Shirasu K. Autophagy negatively regulates cell death by controlling NPR1-dependent salicylic acid signaling during senescence and the innate immune response in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2009;21:2914–27. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.068635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hofius D, Munch D, Bressendorff S, Mundy J, Petersen M. Role of autophagy in disease resistance and hypersensitive response-associated cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:1257–62. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]