Abstract

We recently described the glucosinolate transporters GTR1 and GTR2 as actively contributing to the establishment of tissue-specific distribution of the defense compounds glucosinolates in vegetative Arabidopsis plants. Upon bolting and thereby development of the inflorescence and initiation of seed setting, the spatial distribution of glucosinolates does undergo major changes. Here we investigate the role of GTR1 and GTR2 in establishment of glucosinolate source-sink relationships in bolting plants. By in vivo feeding the exogenous p-hydroxybenzylglucosinolate to a rosette leaf or the roots of wildtype and a gtr1 gtr2 mutant, we show that this glucosinolate can specifically translocate from the rosette and the roots to the inflorescence in a GTR1- and GTR2-dependent manner. This marks that, upon bolting, the inflorescence rather than the roots constitute the strongest sink for leaf glucosinolates compared with plants in vegetative state.

Keywords: glucosinolate, transport, roots, feeding, Arabidopsis, chemical defense distribution, specialized/secondary metabolites

A major component of the chemical defense system in Arabidopsis is the specialized metabolites glucosinolates (GLS).1,2 GLS concentrations in leaves decrease with age until virtually absent upon senescence, where accumulation only occurs in the seeds.3 Recently, we identified 2 vasculature-localized GLS transporters (GTR1 and GTR2) in Arabidopsis. These transporters facilitate import of GLS from maternal tissues into seeds.4 By employing in vivo feeding and micrografting techniques, we further showed that GLS can translocate between rosettes and roots in a GTR1- and GTR2-dependent manner,5 thereby providing evidence that the root can serve as a sink for GLS at this developmental stage. As the plant progresses from a vegetative stage into bolting and seed production, major changes are likely to occur in the source-sink relationships for GLS. Hence, in the current study, we investigate the source-sink relationships between root, rosette and inflorescence of exogenously fed p-hydroxybenzyl GLS (pOHB) in plants after the onset of bolting.

Results

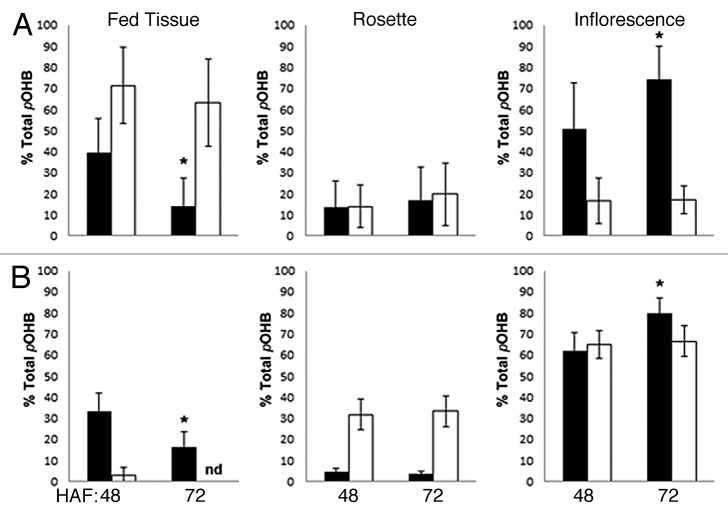

pOHB was fed to leaves of hydroponically grown 5-week-old seed-setting plants. Roots, rosettes, and inflorescences were analyzed separately for pOHB content 48 and 72 h after feeding (HAF). In the wildtype, the pOHB content in the fed rosette leaf decreased significantly from constituting ~40% of the total plant content 48 HAF to ~15% 72 HAF(P < 0.01) (Fig. 1A). This decrease was accompanied by a corresponding increase from ~50% to ~75% in the inflorescence (P < 0.01). No changes were observed in the remaining rosette leaves (Fig. 1A). In the gtr1gtr2 mutant, no significant changes in pOHB distribution were observed in any of the analyzed tissues and ~70% of the total plant pOHB was retained in the fed leaf (Fig. 1A). Notably, pOHB was not detected in the roots of either wildtype or gtr1gtr2. We subsequently investigated the GLS distribution upward from the roots at this developmental stage, by incubating 5-week-old wildtype and gtr1gtr2 plants in media containing pOHB. In the wildtype, the pOHB content in the fed roots decreased from ~32% of the total plant content 48 HAF to ~15% 72 HAF (P < 0.01) (Fig. 1B). This was accompanied by an increase to ~80% in the inflorescence (P < 0.01), while the content in the rosettes remained at ~5% (Fig. 1B). In the gtr1gtr2 mutant, only minute amounts of pOHB were detected and no changes in the distribution were observed between 48 and 72 HAF (Fig. 1B). The total amount of pOHB recovered in leaf and root feeding experiments ranged from 2.43 +/− 1.26 to 35.7 +/− 26.1 nmol (Table 1).

Figure 1. Distribution of leaf- and root-fed p-hydroxybenzylglucosinolate. Hydroponically grown 5-week-old wildtype (Col-0) and gtr1gtr2 plants were fed with the exogenous p-hydroxybenzylglucosinolate (pOHB) for a total timespan of 72 h. The content of pOHB was analyzed in the separate tissues by HPLC and normalized to the total content of the plant. (A) Infiltration of pOHB to a rosette leaf. (B) Feeding of pOHB to roots by addition of pOHB to the growth media. Total amount of recovered pOHB can be found in Table 1. HAF; hours after feeding, nd; none detected. Solid bars represent wild-type plants and open bars represent the gtr1gtr2 mutant. * P < 0.01 (Student t-test vs corresponding tissue at 48 h. Bars are average, ± SD, n = 10).

Table 1. Total amount of pOHB (nmol) in plants 48 and 72 h after feeding (HAF). Numbers are average (n = 10), in parentheses are SD.

| Leaf feeding | Rootfeeding | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 48HAF | 72HAF | 48HAF | 72HAF | |

| WT | 13.7 | 6.54 | 6.5 | 9.32 |

| (11.7) | (7.0) | (2.67) | (4.73) | |

| gtr1gtr2 | 35.7 | 29.8 | 2.43 | 5.75 |

| (26.1) | (17.3) | (1.26) | (2.91) | |

Discussion

Prior studies indicate that transport of glucosinolates occur from the rosette to reproductive tissue in Arabidopsis.5,7 We have previously shown that pOHB is a substrate for GTR1 and GTR2 expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes4 and that it is distributed identically to the aliphatic 2-propenyl GLS upon feeding to both leaves and roots.5 Hence, we utilized pOHB as a model GLS to investigate source/sink relationship for endogenous GLS in bolting Arabidopsis plants. In contrast to the previously observed GTR-dependent transport of leaf-fed pOHB from rosette to root in vegetative plants,5 we solely detected GTR-dependent upward transport of leaf-fed pOHB to the inflorescence (Fig. 1A). Besides illustrating that GTR1 and GTR2 also mediate retention of GLS in the roots at this developmental stage, our data demonstrates a shift in GLS sink strength between the root and inflorescence upon bolting compared with vegetative plants. The results suggest that, similar to in vegetative plants, GLS can move between tissues GTR1- and GTR2-dependently in the bolting plant, and that endogenous GLS may be transported from both the rosette and roots to the inflorescence in a GTR1- and GTR2-dependent manner when the plant changes its life strategy from the vegetative stage to development of inflorescence with seeds that represent a strong sink for GLS. Glucosinolate movement to the inflorescences upon bolting is likely to reflect a need of the plant to protect plant parts with high fitness value, i.e., flowers, fruits, and seeds, from herbivore and pathogen enemies.

Methods

GLS feeding and analysis

GLS were analyzed as desulfo GLS as previously described.5 To evaluate root uptake pOHB was added to growth media to a final concentration of 200 μM. Feeding to leaves was done by infiltrating max 4 μL Murashige and Skoog (MS) media adjusted to pH 5,6 containing 10 mM p-OHB directly to a leaf using a 1 mL syringe with a 10 μL pipette tip. After 48 and 72 h incubation, plant organs from 10 individual plants were harvested, washed 3 times in water, and analyzed for GLS content as described elsewhere.

Plant growth conditions

Arabidopsis thaliana (Col-0) plants were grown in a hydroponic system as previously described.5

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.D’Auria JC, Gershenzon J. The secondary metabolism of Arabidopsis thaliana: growing like a weed. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2005;8:308–16. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halkier BA, Gershenzon J. Biology and biochemistry of glucosinolates. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:303–33. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown PD, Tokuhisa JG, Reichelt M, Gershenzon J. Variation of glucosinolate accumulation among different organs and developmental stages of Arabidopsis thaliana. Phytochemistry. 2003;62:471–81. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(02)00549-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nour-Eldin HH, Andersen TG, Burow M, Madsen SR, Jørgensen ME, Olsen CE, Dreyer I, Hedrich R, Geiger D, Halkier BA. NRT/PTR transporters are essential for translocation of glucosinolate defence compounds to seeds. Nature. 2012;488:531–4. doi: 10.1038/nature11285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andersen TG, Nour-Eldin HH, Fuller VL, Olsen CE, Burow M, Halkier BA. Integration of biosynthesis and long-distance transport establish organ-specific glucosinolate profiles in vegetative Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2013;25:3133–45. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.110890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petersen BL, Chen S, Hansen CH, Olsen CE, Halkier BA. Composition and content of glucosinolates in developing Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta. 2002;214:562–71. doi: 10.1007/s004250100659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellerbrock BLj, Kim JH, Jander G. Contribution of glucosinolate transport to Arabidopsis defense responses. Plant Signal Behav. 2007;2:282–3. doi: 10.4161/psb.2.4.4014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]