Abstract

Objectives

Chronic transplant dysfunction after kidney transplantation is a major reason of kidney graft loss and is caused by immunological and non-immunological factors. There is evidence that mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) may exert a positive effect on renal damage in addition to immunosuppression, by its direct antifibrotic properties. The aim of our study was to retrospectively investigate the role of MMF doses on progression of chronic allograft dysfunction and fibrosis and tubular atrophy (IF/TA).

Setting

Retrospective, cohort study.

Participants

Patients with kidney transplant in a tertiary care institution. This is a retrospective cohort study that included 79 patients with kidney and kidney–pancreas transplantation. Immunosuppression consisted of anti-interleukin 2 antibody induction, MMF, a calcineurin inhibitor±steroids.

Primary outcome measures

An association of average MMF doses over 1 year post-transplant with progression of interstitial fibrosis (Δci), tubular atrophy (Δct) and estimated-creatinine clearance (eCrcl) at 1 year post-transplant was evaluated using univariate and multivariate analyses.

Results

A higher average MMF dose was significantly independently associated with better eCrcl at 1 year post-transplant (b=0.21±0.1, p=0.04). In multiple regression analysis lower Δci (b=−0.2±0.09, p=0.05) and Δct (b=−0.29±0.1, p=0.02) were independently associated with a greater average MMF dose. There was no correlation between average MMF doses and incidence of acute rejection (p=0.68).

Conclusions

A higher average MMF dose over 1 year is associated with better renal function and slower progression of IF/TA, at least partly independent of its immunosuppressive effects.

Keywords: Transplant Medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

An important novel finding in our study is that greater average mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) exposure was strongly negatively correlated with fibrosis and tubular atrophy (IF/TA) progression during the first year after kidney transplantation.

Patients on higher average doses of MMF (up to 4 g daily) during 1 year post-transplantation had significantly lower progression of graft interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy. This is an important finding because of the predictive value of graft IF/TA and should translate into better long-term graft survival.

Our study has several shortcomings, such as its retrospective aspect and relatively short study period.

As it was not the aim of the study, we did not report side effects associated with different dosages of MMF.

Introduction

Kidney transplantation significantly improves patient survival and quality of life as compared to dialysis. While significant improvements have been made in the treatment of acute rejection and short survival of transplanted kidney, there has not been any major improvement in the long-term survival of transplanted kidney.1 Chronic transplant dysfunction after kidney transplantation is a major cause of kidney graft loss and is evoked by immunological and non-immunological factors.2 3 Histology changes that determine chronic transplant dysfunction are interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy (IF/TA), arteriosclerosis, arteriolar hyalinosis, glomerulopathy and mesangial matrix expansion.4 IF/TA is the major pathohystology finding that can be verified on graft biopsies after kidney transplantation and is a predictor of long-term allograft function.4 Clinical factors that affect progression of IF/TA are: recipient age, human leucocyte antigen (HLA) mismatch, episodes of severe acute rejection, chronic rejection (especially antibody mediated), use of calcineurin inhibitors (CNI) and BK nephropathy. Avoidance of CNI toxicity is considered as an important step to slow progression of IF/TA.4–7 Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) may help in lowering CNI toxicity, by allowing lower CNI exposure.7

MMF reduces the risk of acute allograft rejection, without nephrotoxic side effects, and is an ideal candidate for long-term calcineurin drug reduction treatment strategies.7 Retrospective studies of renal recipients who were treated with MMF comparing azathioprin showed that MMF-treated patients had significantly less chronic allograft dysfunction.8 9 Besides being associated with lower acute rejection rates as compared to azathioprin,10 11 evidence from animal and human studies suggests that MMF may also exert direct antifibrotic properties due to its antiproliferative action on non-immune cells, including renal tubular cells and vascular smooth muscle cells.12 13

The aim of our study was to investigate the role of MMF doses on progression of IF/TA in kidney transplant recipients.

Patients and methods

Patients

This is a retrospective study conducted at Clinical Hospital ‘Merkur’. This study represents a part of the post-transplant immune monitoring at the Merkur hospital, approved by the Hospital Ethics Committee. Patients gave their informed written consent for anonymised transplant data collection for research purposes. The study included 79 patients with kidney and kidney-pancreas transplantation performed between 2003 and 2011. Eligible patients had to have protocol kidney biopsy at the time of implantation and 12 months after transplantation. Exclusion criteria have been: dual kidney transplantation, kidney–liver transplantation, use of antithymocyte immunoglobulin, BK nephropathy and recurrence of glomerulonephritis after transplantation.

Immunosuppression

Induction immunosupression consisted of an anti-interleukin 2 (IL2) antibody (daclizumab or basiliximab), CNI (tacrolimus or cyclosporine), MMF and methylprednisolone. Maintenance immunosuppression consisted of a CNI (tacrolimus or cyclosporine), MMF±steroids. Target cyclosporine trough concentrations were 250–350 during first month post-transplant, 200–300 during second to sixth months and 100–150 µg/L thereafter. Target tacrolimus trough levels were 10–12 during first month, 8–10 during second to sixth months and 5–8 µg/L thereafter. Mycophenolic acid target trough concentration was aimed to be higher than 7.2 µmol/L with tacrolimus and higher than 5 µmol/L with cyclosporine use.

Daclizumab was administered at day 0 in a dose of 2 mg/kg intravenously before opening of vascular anastomosis and at day 14 in a dose of 2 mg/kg intravenously. Basiliximab was administered at day 0 in a dose of 20 mg intravenously before opening of vascular anastomosis and at day 4 as 20 mg intravenously.

Steroids were dosed as follows: day 0: intraoperatively 500 mg of methylprednisolone, day 1 250 mg, day 2 125 mg, day 3 80 mg and day 4 40 mg. In patients with early steroid withdrawal steroids were withdrawn at day 5 after transplantation. In patients maintained on steroids, nadir dose of prednisone was 5 mg/day, achieved by 6 months. The criteria for early elimination of steroids were low immunological risk of the recipient (absence of, or low degree of HLA sensitisation, ie, panel reactive antibodies <10%) and good immediate renal function, as well as absence of an episode of acute rejection within 5 days after the transplantation. Steroids were reintroduced in patients who suffered acute rejection episodes.

As prophylaxis for viral (herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus), fungal (Candida spp.) urinary and Pneumocystis jiroveci infections, low-dose fluconazole (for 1 year), valganciclovir (universally for 3 months) and sulfamethoxazol and trimethoprim (for 1 year) were used.

Renal allograft biopsies

Protocol kidney biopsies were performed at implantation and 1, 3, 6 and 12 months after transplantation. For cause, biopsies were performed in case of unexplained deterioration of renal function, or once weekly in patients with delayed graft function (DGF). All rejection episodes were histologically confirmed. Histopathological analysis was performed by either of two pathologists who were blinded for immunosuppression. Acute rejections and chronic allograft scores were analysed using Banff 97 classification and its updates.14 15 All protocol and indication biopsies were analysed by light microscopy, by immunofluorescence for C4d and, if indicated by immunohistochemistry, for BK virus. Biopsies at 1 year post-transplant were also analysed by electron microscopy for signs of chronic antibody-mediated rejection (transplant glomerulopathy, peritubular capillary basement membrane multilayering).16

Clinical outcome parameters

Progression of chronic allograft scores during 1 year post-transplant was calculated by subtracting implantation chronic scores from chronic allograft scores 12 months post-transplant: interstitial fibrosis (Δci), tubular atrophy (Δct), glomerulosclerosis (Δcg), mesangial matrix increase (Δmm), vasculopathy (Δcv) and arteriolar hyalinosis (Δah). Estimated creatinine clearance (eCrcl) at 3, 6 and 12 months post-transplant was calculated using Cockroft-Gault formula. Acute rejections with Banff grade IA and IB were treated with three 500 mg methylprednisolone pulses. In case of acute rejection grade IIA or greater, patients were treated with antithymocyte globulin. Antibody-mediated rejections were treated with steroid pulse and plasmapheresis.

The average dose of MMF during 1 year post-transplant was calculated from MMF doses at months 1, 3, 6 and 12.

Adverse effects analysed were clinically significant leucopaenia, defined as white cell count less than 3000/mL, time to first symptomatic infection and number of symptomatic infection episodes per patient during the first post-transplant year.

Statistical analysis

Numerical data are presented as mean±SD or median with range in case of not normal distribution. Normality of distribution was tested with Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Correlation between two continuous variables was tested using Spearman non-parametric correlation. Difference between two groups in continuous variables was tested with student t test or with Mann-Whitney test in non-normally distributed variables. The significance of the progression in chronic scores was analysed using Wilcoxon Matched Pairs test. Univariate and multiple linear regression analyses were performed to determine predictive factors for progression of chronic allograft scores and kidney function at 12 months after transplantation. All variables that were associated with respective outcome in bivariate analysis (at p=0.1) were included in the multivariate analysis. Owing to co-linearity between ci and ct scores, only one score was included in each multivariate analysis. Statistical significance was considered at p<0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using Statistica V.10 (StatSoft, Tulsa, Oklahoma, USA).

Results

Patient and transplant characteristics

Patient characteristics are shown in table 1. Recipients were a mean of 44.67±12.03-years old at the time of transplantation, 68% were men and all were Caucasians. Thirty-three per cent of recipients had DGF after transplantation. Donors were a mean of 43.89±15.55 years old and 54% were men. The number of living donor transplantations was 24 (30%). The average daily MMF dose during 1 year post-transplant was 2244±585 mg (1062–4000; table 2). As expected, there was no correlation of MMF dose with MMF trough concentration (R=−0.13; p=0.28). Also, there was no correlation between MMF dose with tacrolimus concentration (R=−0.04; p=0.79). Early steroid withdrawal was carried out in 46% of patients after transplantation. Incidence of subclinical and clinical acute rejections greater than borderline was 30% in the first year. There was no correlation between average MMF dose and incidence of acute rejection (p=0.68).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Recipient characteristics | |

| Age (years) | 44.67±12.03 |

| Gender (female/male) | 25/54 |

| Primary renal disease (diabetes mellitus, polycistic kidney disease, glomerulonephritis, pyelonephritis/interstitial nephritis, other/unknown) | 24/8/19/6/22 |

| Donor characteristics | |

| Donor source (deceased/living) | 55/24 |

| Age (years) | 43.89±15.55 |

| Gender (female/male) | 36/43 |

| Transplantation characteristics | |

| Transplanted organ (KIDNEY/SPKT) | 58/21 |

| Initial immunosuppression (anti-IL2, TAC, MMF/anti-IL2, CyA, MMF) | 53/26 |

| Delayed graft function (no/yes) | 53/26 |

| Steroid free (yes/no) | 36/43 |

| HLA MM | 3.33±1.51 |

HLA, human leucocyte antigen; Il2, interleukin 2; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MM, mismatch; SPKT, simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplant.

Table 2.

eCrcl, MMF dose and CNI concentration during first year post-transplant

| Month post-transplant | 1 | 3 | 6 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| eCrcl (mL/min) | 56.98±15.79 | 58.94±16.94 | 61.47±16.75 | |

| MMF dose (mg) | 2500 (750–4000) 2427±643.17 |

2000 (750–4000) 2167.72±733.49 |

2000 (1000–4000) 2188.29±716.91 |

2000 (1000–4000) 2193.04±642.95 |

| Tacrolimus concentration (µg/L) (n=53) |

10.79±4.16 | 9.69±3.00 | 9.03±5.52 | 7.83±2.45 |

| Cyclosporin concentration (µg/L) (n=26) |

335.07 (274–413) | 231.05 (181–265) | 206 (170–257) | 131 (125–171) |

CNI, calcineurin inhibitors; eCrcl, estimated-creatinine clearance (eCrcl); MMF, mycophenolate mofetil.

Factors associating with eCrcl

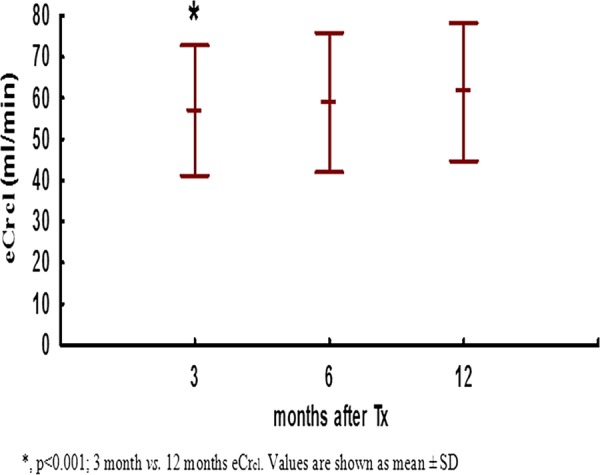

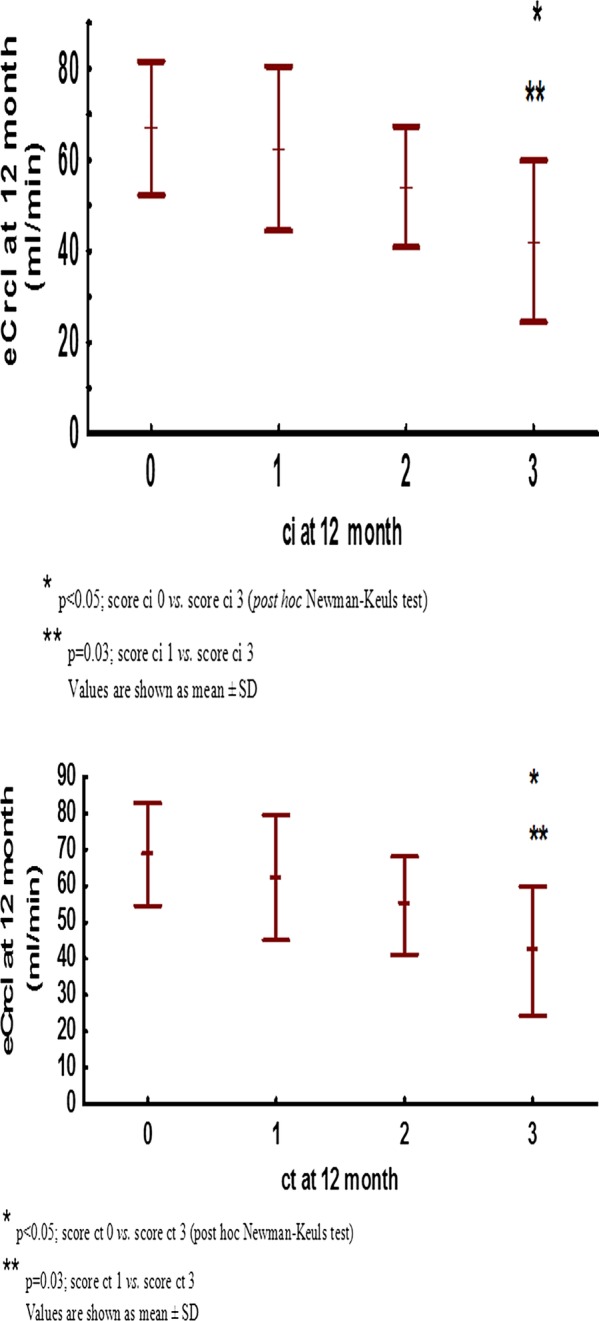

Kidney function increased during first year post-transplant. eCrcl at month 3 was 56.98±15.78 mL/min, at 6 months 58.94±16.94 mL/min and at 12 months 61.47±16.75 mL/min (p<0.001; 12 months versus 3 months; figure 1.) eCrcl at 1 year post-transplant was greater in simultaneous pancreas–kidney transplant recipients (71.38±13.45 vs 57.88±16.47 mL/min; p=0.001) and in patients who did not have DGF (64.08±15.87 vs 56.15±17.55 mL/min; p=0.05). Donor age (R=−0.46; p<0.001) and recipient age (R=−0.46; p<0.001) negatively correlated with eCrcl at 1 year post-transplant, while there was no correlation of renal function with donor and recipient gender, type of donation (deceased vs living), HLA MM, average CNI concentration, steroid-free regimen of immunosuppression or history of acute rejection (table 3). In univariate analysis allograft function at 12 months post-transplant was also negatively correlated with ci (R=−0.34; p=0.002) and ct (R=−0.35; p=0.002) at 12 months (figure 2A, B). Although the MMF dose was positively correlated with renal function with borderline significance in univariate analysis, in multivariate analysis there was a significant positive association between a greater average MMF dose and better eCrcl at 12 months post-transplant (b=0.21±0.1; p=0.04; table 4).

Figure 1.

Estimated-creatinine clearance during first year post-transplant.

Table 3.

Association of variables with eCrcl on 1 year

| Estimated-creatinine clearance (mL/min) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Kidney vs SPKT | 57.88±15.47 vs 71.38±13.45 | 0.001 |

| DGF (yes vs no) | 56.15±17.55 vs 64.08±15.87 | 0.05 |

| Recipient gender (m vs f) | 59.83±16.02 vs 65±18.07 | 0.2 |

| Donor gender (m vs f) | 63.87±16.71 vs 58.60±16.58 | 0.17 |

| Donor source (D vs L) | 62.36±17.85 vs 59.43±14.05 | 0.47 |

| Steroid-free (yes vs no) | 63.94±17.73 vs 59.39±15.81 | 0.23 |

| Acute rejection (yes vs no) | 61.64±16.59 vs 61.39±16.97 | 0.95 |

| R | p Value | |

| Recipient age | −0.45 | <0.001 |

| Donor age | −0.46 | <0.001 |

| HLA MM | 0.07 | 0.52 |

| Average tacrolimus concentration | −0.02 | 0.9 |

| Average MMF dose | 0.18 | 0.1 |

| ci at 1 year post-transplantation | −0.34 | 0.002 |

| ct at 1 year post-transplantation | −0.35 | 0.002 |

| cv at 1 year post-transplantation | −0.20 | 0.07 |

DGF, delayed graft function; HLA, human leucocyte antigen; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MM, mismatch; SPKT, simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplant.

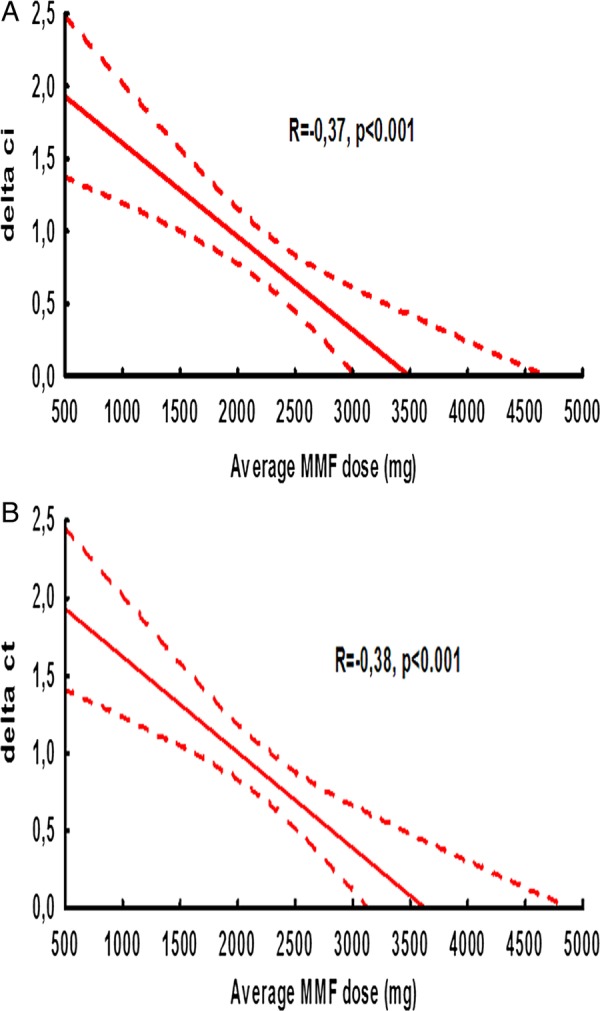

Figure 2.

Correlation between average mycophenolate mofetil dose and progression of (A) ci score and (B) ct score.

Table 4.

Multiple regression analysis of factors associated with kidney function

| Beta (β) | SE β | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tx (kidney) | −0.17 | 0.13 | 0.19 |

| DGF (no) | 0.04 | 0.1 | 0.71 |

| Recipient age | −0.41 | 0.1 | <0.001 |

| Donor age | −0.1 | 0.14 | 0.45 |

| ci at 12 months | −0.18 | 0.11 | 0.09 |

| Average MMF dose | 0.21 | 0.1 | 0.04 |

DGF, delayed graft function; MMF,mycophenolate mofetil.

Factors affecting IF/TA

The average ci score increased from 0.16±0.44 to 0.94±0.86 between implantation and month 12 (p<0.001). Average progression of this and other chronic scores during 1 year post-transplant is shown in table 5. In univariate analysis Δci (R=−0.37; p=0.001) and Δct (R=−0.38; p=0.001) significantly negatively correlated with average MMF dose (figure 3A, B, table 6). There was lower progression of ci score in patients on steroid-free immunosuppression (0.47±0.7 vs 1.09±0.87; p=0.002) and in those who did not have DGF (0.62±0.74 vs 1.19±0.98; p=0.02). Acute cellular rejection, recipient and donor gender, recipient and donor age, HLA MM, deceased vs living donor, as well as average concentration of tacrolimus had no significant effect on progression of chronic allograft scores. A higher average MMF dose was associated with lower progression of ci and ct score regardless of CNI type (data not shown). Factors that remained significantly associated with progression of ci score in multivariate analysis were ci score, donor age, average MMF dose, DGF and steroid-free immunosuppression (table 7). In multivariate analysis only ct0 score, average MMF dose and DGF remained independently associated with a 12-month progression of ct score (table 7); selected adverse events (AE) are shown in table 8. There was no difference in AE (leucopaenia and infections) with respect to average median MMF dose.

Table 5.

One-year progression of chronic allograft scores

| Banff score | N | At transplantation | N | 12 month | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interstitial fibrosis (ci) | 79 | 0.16±0.44 | 79 | 0.94±0.85 | <0.001 |

| Tubular atrophy (ct) | 79 | 0.24±0.46 | 79 | 1.05±0.77 | <0.001 |

| Chronic glomerulopathy (cg) | 79 | 0 | 79 | 0 | |

| Mesangial matrix (mm) | 79 | 0.01±0.11 | 79 | 0.09±0.36 | 0.09 |

| Fibrointimal thickening (cv) | 76 | 0.37±0.83 | 78 | 0.29±0.70 | 0.47 |

| Arteriolar hyalinosis (ah) | 78 | 0.68±1.04 | 79 | 0.79±1.04 | 0.26 |

Figure 3.

Estimated-creatinine clearance by (A) ci score and (B) ct score.

Table 6.

Correlation of factors associated with progression of ci and ct scores

| Δci |

Δct |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±SD | p Value | Mean±SD | p Value | |

| Kidney vs SPKT | 0.86±0.91 vs 0.67±0.73 | 0.51 | 0.85±0.87 vs 0.86±0.65 | 0.74 |

| DGF (yes vs no) | 1.19±0.98 vs 0.62±0.74 | 0.02 | 1.15±0.92 vs 0.69±0.72 | 0.05 |

| Recipient gender (male vs female) | 0.83±0.88 vs 0.76±0.83 | 0.78 | 0.91±0.83 vs 0.72±0.79 | 0.35 |

| Donor gender (male vs female) | 0.91±0.95 vs 0.69±0.75 | 0.43 | 0.88±0.93 vs 0.81±0.67 | 0.96 |

| Donor source (D vs L) | 0.84±0.88 vs 0.75±0.85 | 0.73 | 0.87±0.82 vs 0.79±0.83 | 0.71 |

| Steroid free (no vs yes) | 1.09±0.87 vs 0.47±0.74 | 0.002 | 1.07±0.83 vs 0.58±0.73 | 0.01 |

| Acute rejection (yes vs no) | 0.8±0.89 vs 0.83±0.82 | 0.78 | 0.93±0.84 vs 0.67±0.76 | 0.23 |

| R | p Value | R | p Value | |

| Recipient age | −0.11 | 0.33 | −0.11 | 0.32 |

| Donor age | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.73 |

| HLA MM | −0.09 | 0.43 | −0.002 | 0.99 |

| Average tacrolimus concentration | −0.009 | 0.95 | 0.003 | 0.98 |

| Average MMF dose | −0.37 | <0.001 | −0.38 | <0.001 |

| ci at implantation | −0.32 | 0.003 | ||

| ct at implantation | −0.45 | <0.001 | ||

DGF, delayed graft function; HLA, human leucocyte antigen; MM, mismatch; SPKT, simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplant.

Table 7.

Multivariate general regression analysis for factors related to progression of ci and ct score

| Beta (β) | SE β | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Δci | |||

| ci0 | −0.43 | 0.09 | <0.001 |

| DGF (no) | −0.22 | 0.11 | <0.05 |

| Average MMF dose | −0.20 | 0.09 | <0.05 |

| Donor age | 0.32 | 0.09 | <0.05 |

| Steroid free (yes) | −0.25 | 0.11 | 0.02 |

| Δct | |||

| ct0 | −0.44 | 0.09 | <0.001 |

| Average MMF dose | −0.29 | 0.1 | <0.05 |

| DGF (no) | −0.29 | 0.1 | <0.05 |

| Steroid free (yes) | −0.09 | 0.11 | 0.39 |

DGF, delayed graft function; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil.

Table 8.

Adverse events with respect to 1 year average median MMF dose

| MMF dose <median | MMF dose >median | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average number of infection episodes per patient | 1.16±0.97 | 1.23±1.22 | 0.88 |

| Mean time to first infection (days) | 157±138 | 175±143 | 0.76 |

| Proportion of patients with leucopaenia | 6/31 | 7/48 | 0.58 |

MMF, mycophenolate mofetil.

Discussion

The most important novel finding in our study is that greater average MMF exposure was strongly negatively correlated with IF/TA progression during first year after kidney transplantation. Patients on higher average doses of MMF during 1 year post-transplantation had significantly lower progression of ci and ct scores. To our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating that there is a dose-dependent protective effect of MMF on graft IF/TA. Lower progression of IF/TA could not be explained with lower concentration of CNI, because there was no correlation between tacrolimus concentration with IF/TA. Similarly, there was no correlation between average MMF dose and tacrolimus (R=−0.04; p=0.79) or cyclosporine concentration (R=−0.07, p=0.79). In addition, a higher average MMF dose was not associated with decreased incidence of biopsy proven acute rejection, which suggests that antifibrotic properties of a higher MMF dose was at least partly independent of its immunosuppressive effects. Higher MMF doses had only moderate effect on 1-year renal function, which is consistent with previous reports showing that transplanted kidneys undergo pathohystology changes without significant early change in kidney function.4

In the present retrospective study we have confirmed that IF/TA progression occurs in the first year after kidney transplantation. Several studies have shown that progression of IF/TA is correlated with a type of immunosuppression.17 In most transplant centres in the USA and Europe, immunosuppression consists of induction with an anti-IL2R antibody or antithymocyte immunoglobulin and maintenance with a CNI, MMF and steroids.18 Studies have reported significant improvement in kidney function in patients on MMF with lower exposition to CNIs, especially tacrolimus.19 Recently, Kamar et al20 reported that maintenance patients with kidney transplant who converted to a higher dose of mycophenolate sodium (1440 mg daily) with lower tacrolimus concentration had borderline higher eCrcl on month 6 vs those treated with a lower dose of mycophenolate sodium, with usual tacrolimus concentration (eCrcl 49.1±11.1 vs 44.7±11.5 mL/min; p=0.07). Although there was only borderline significance, increased mycophenolate dosing with lower tacrolimus concentration was safe with potential benefit on kidney function.

Our study also corroborates recently published findings of a post hoc joint analysis of the Symphony, FDCC and OptiCept trials, where a lower tacrolimus level and a higher MMF dose were associated with significantly better kidney function at 1 year post-transplant.19 A shortcoming of these studies4 17 is lack of protocol biopsies. Optimal MMF dosing in patients maintained on contemporary low-dose CNI is still undetermined. However, some results of early MMF registration trials suggest that higher MMF exposure might be beneficial; it must be kept in mind that there was no antibody induction in these studies and that CNI was standard dose cyclosporine. Thus, in the Tri-continental study, the group treated with 3 g MMF compared with 2 g of MMF showed lower incidence of biopsy proven acute rejection episodes (15.9% vs 19.7%) within a 6 month period selected for the primary efficacy analysis. Similarly, serum creatinine level at 1 year was 1.42±0.07 mg/dL in the MMF 3 g group vs 1.64±0.07 mg/dL in the MMF 2 g group.12 In the European MMF study the same trends regarding higher MMF dose were observed.11 As mentioned before, in these studies there was no antibody induction that could have allowed lower dose of cyclosporin with higher dose of MMF and there were no protocol biopsies. In a recent MYSS trial, there was no difference in acute rejection rate and renal function between MMF and azathioprine in a cyclosporine-based protocol.18 However, in that study only one MMF dose was compared to azathioprine21 and again there were no protocol biopsies.

Unfortunately, adequate prospective MMF dose comparison studies in tacrolimus-based protocols with antibody induction are missing. In the Symphony study it was reported that patients on tacrolimus-MMF-prednisolone maintenance immunosuppression after kidney transplantation had better kidney function and graft survival with a lower number of acute rejection episodes. Patients in that group had highest MMF exposure.22 Protocols with even higher MMF exposure might allow additional CNI sparing, decreasing the side effects of CNI (hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, neurotoxicity).1

Clinical relevance of IF/TA without other concomitant pathology (ie, recurrent disease and chronic antibody-mediated rejection) for prediction of graft deterioration and loss is controversial. In the study by El-Zoghby et al there was an attempt to identify specific causes of late kidney allograft failure. The authors found that transplant glomerulopathy was responsible for 37% loss of functioning grafts, while graft loss due to IF/TA was present in 31% of cases (with higher frequency in deceased-donor transplants).23 At first glance, these results seem at odds with ours, where there were no signs of chronic antibody-mediated rejection. An explanation for this discrepancy in the results of the two studies is not completely clear, but the former study included a high number of living transplants (72.5%) with glomerulonephritis as primary disease and with follow-up of up to 10 years. Transplant glomerulopathy is more frequently seen late post-transplant, generally with low incidence. Nevertheless, ours and El-Zoghby study demonstrated that IF/TA even in absence of other pathology is associated with adverse graft outcome. Another important study, the DeKaf study, tried to use various histopathological clusters to differentiate subgroups within diagnosis of IF/TA. They found that the cluster with more severe fibrosis plus inflammation and arterial lesions had the worst prognosis.24 Although incidence of acute rejection in our study did not vary with MMF exposure, increased MMF exposure might suppress mild graft inflammation, below the threshold for diagnosing acute rejection. This is the subject of our ongoing investigation and will be reported separately. An interesting finding of the present study was that early steroid withdrawal was not associated with worse IF/TA. At first glance this is at odds with the Astellas trial.21 However, according to our protocol, patients with DGF were not included in early steroid withdrawal and the Astellas trial (which did not have protocol biopsies), reported increased IF/TA in an early steroid withdrawal group based on indication biopsies performed early post-transplant, and were thus more likely reflecting donor-derived histology changes, rather than the effect of steroid withdrawal.25

In our study there was only borderline significance of positive association of 1-year eCrcl with MMF in univariate analysis. This result is not very surprising since decreased renal function is not a very sensitive marker of incipient IF/TA.

Mechanisms by which an average higher exposure to MMF was associated with slower progression of IF/TA may be immune and non-immune. Owing to the fact that there was no difference in incidence of acute rejection with respect to increased MMF exposure in our study, we believe that there may be a significant contribution of non-immune mechanisms in retardation of IF/TA in patients with higher MMF. In line with this, in many experimental models it has been shown that MMF has antiproliferative and antifibrotic effects.13 26 27 In the study of Jiang et al using rat renal ischaemia reperfusion injury, a time-dependent and dose-dependent correlation of higher MMF dose with better renal function and lower interstitial fibrosis was demonstrated. Suggested potential mechanism was a lower expression of transforming growth factor-β1 and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) with lower macrophage infiltration.27 In recent clinical trials MMF was shown as a safe drug that could be a good candidate for treatment of interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis.28 An experimental model of encapsulated peritoneal sclerosis in rats proved the beneficial effect of MMF as an inhibitor of neovascularisation.29 Also, MMF monotherapy was associated with a positive effect on hepatic fibrosis progression in hepatitis C virus liver transplant recipients.30

Our study has several shortcomings, such as its retrospective aspect and relatively short study period. Although the study period was limited to 12 months post-transplantation, a clear correlation of slower progression of IF/TA with a higher average MMF dose underlines the potential benefit of these findings. As mentioned before, in the current study we did not analyse inflammation outside Banff acute rejection threshold in kidney biopsies with respect to MMF dose. As inflammation in areas of IF/TA is an important predictor of renal function and graft loss, it is the subject of an ongoing work.

In summary, higher MMF dose after kidney transplantation might slower progression of IF/TA, which can lead to better long-term survival of transplanted kidney. Our Our study serves as a platform for a prospective, randomised, long-term trial with different MMF doses we are currently conducting (trial registration number: NCT018600183) to evaluate the benefits of higher MMF doses in renal transplant recipients.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: KM participated in research design, collected and analysed data, and wrote the paper. BM, SB and DGL participated in collecting and analysing data. BK, DG, ZV and MSM participated in collecting data. MK proposed research design, analysed data and participated in writing the paper.

Funding: Funding support from Grant by the Ministry of Science, Technology and Sports of the Republic of Croatia to Dr Mladen Knotek.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: University Hospital Merkur Ethics Review Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Pascual M, Theruvath T, Kawai T, et al. Strategies to improve long-term outcomes after renal transplantation. N Engl J Med 2002;346:580–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuypers DR, Chapman JR, O'Connell PJ, et al. Predictors of renal transplant histology at three months. Transplantation 1999;67:1222–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matas AJ, Gillingham KJ, Payne WD, et al. The impact of an acute rejection episode on long-term renal allograft survival (t1/2). Transplantation 1994;57:857–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nankivell BJ, Borrows RJ, Fung CL, et al. The natural history of chronic allograft nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2003;349:2326–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birnbaum LM, Lipman M, Paraskevas S, et al. Management of chronic allograft nephropathy: a systematic review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;4:860–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frimat L, Cassuto-Viguier E, Charpentier B, et al. Impact of cyclosporine reduction with MMF: a randomized trial in chronic allograft dysfunction. The ‘reference’ study. Am J Transplant 2006;6:2725–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ekberg H, Tedesco-Silva H, Demirbas A, et al. Reduced exposure to calcineurin inhibitors in renal transplantation. N Engl J Med 2007;357:2562–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azuma H, Binder J, Heemann U, et al. Effects of RS61443 on functional and morphological changes in chronically rejecting rat kidney allografts. Transplantation 1995;59:460–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ojo AO, Meier-Kriesche HU, Hanson JA, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil reduces late renal allograft loss independent of acute rejection. Transplantation 2000;69:2405–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Tricontinental Mycophenolate Mofetil Renal Transplantation Study Group. A blinded, randomized clinical trial of mycophenolate mofetil for the prevention of acute rejection in cadaveric renal transplantation. Transplantation 1996;61:722–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.European Mycophenolate Mofetil Cooperative Study Group. Placebo controlled study of mycophenolate mofetil combined with cyclosporin and corticosteroids for prevention of acute rejection. Lancet 1995;345:1321–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Djamali A, Vidyasagar A, Yagci G, et al. Mycophenolic acid may delay allograft fibrosis by inhibiting transforming growth factor-beta1-induced activation of Nox-2 through the nuclear factor-kappa B pathway. Transplantation 2010;90:387–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dell'Oglio MP, Zaza G, Rossini M, et al. The anti-fibrotic effect of mycophenolic acid-induced neutral endopeptidase. J Am Soc Nephrol 2010;21:2157–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Solez K, Colvin RB, Racusen LC, et al. Banff 07 classification of renal allograft pathology: updates and future directions. Am J Transplant 2008;8:753–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Racusen LC, Solez K, Colvin RB, et al. The Banff 97 working classification of renal allograft pathology. Kidney Int 1999;55:713–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roufosse CA, Shore I, Moss J, et al. Peritubular capillary basement membrane multilayering on electron microscopy: a useful marker of early chronic antibody-mediated damage. Transplantation 2012;94:269–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gelens MA, Steegh FM, van Hooff JP, et al. Immunosuppressive regimen and interstitial fibrosis and tubules atrophy at 12 months postrenal transplant. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2012;5:1010–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. 2013 http://srtr.transplant.hrsa.gov/annual_reports/2011/pdf/01_kidney_12.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ekberg H, van GT, Kaplan B, et al. Relationship of tacrolimus exposure and mycophenolate mofetil dose with renal function after renal transplantation. Transplantation 2011;92:82–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamar N, Rostaing L, Cassuto E, et al. A multicenter, randomized trial of increased mycophenolic acid dose using enteric-coated mycophenolate sodium with reduced tacrolimus exposure in maintenance kidney transplant recipients. Clin Nephrol 2012;77:126–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Remuzzi G, Lesti M, Gotti E, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil versus azathioprine for prevention of acute rejection in renal transplantation (MYSS): a randomised trial. Lancet 2004;364:503–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lloberas N, Torras J, Cruzado JM, et al. Influence of MRP2 on MPA pharmacokinetics in renal transplant recipients-results of the Pharmacogenomic Substudy within the Symphony Study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011;26:3784–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.El-Zoghby ZM, Stegall MD, Lager DJ, et al. Identifying specific causes of kidney allograft loss. Am J Transplant 2009;9:527–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matas AJ, Leduc R, Rush D, et al. Histopathologic clusters differentiate subgroups within the nonspecific diagnoses of CAN or CR: preliminary data from the DeKAF study. Am J Transplant 2010;10:315–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woodle ES, First MR, Pirsch J, et al. A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter trial comparing early (7 day) corticosteroid cessation versus long-term, low-dose corticosteroid therapy. Ann Surg 2008;248:564–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luo L, Sun Z, Wu W, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil and FK506 have different effects on kidney allograft fibrosis in rats that underwent chronic allograft nephropathy. BMC Nephrol 2012;13:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang S, Tang Q, Rong R, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil inhibits macrophage infiltration and kidney fibrosis in long-term ischemia-reperfusion injury. Eur J Pharmacol 2012;688:56–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tzouvelekis A, Galanopoulos N, Bouros E, et al. Effect and safety of mycophenolate mofetil or sodium in systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease: a meta-analysis. Pulm Med 2012;2012:143637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hur E, Bozkurt D, Timur O, et al. The effects of mycophenolate mofetil on encapsulated peritoneal sclerosis model in rats. Clin Nephrol 2012;77:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manzia TM, Angelico R, Toti L, et al. Long-term, maintenance MMF monotherapy improves the fibrosis progression in liver transplant recipients with recurrent hepatitis C. Transpl Int 2011;24:461–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.