Abstract

Objective

To determine the incidence of fever among elderly persons under home medical management, diagnosis at fever onset and outcomes from a practical standpoint.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Setting

5 clinics in residential areas of Tokyo that process an average of 50–200 outpatients/day.

Participants

Patients (n=419) aged ≥65 years who received home medical management from the five clinics between 1 October 2009 and 30 September 2010.

Main outcome measures

Fever (≥37.5°C or ≥1.5°C above usual body temperature), diagnosis at onset and outcomes (cure at home, hospitalisation and death).

Results

The incidence of fever was 2.5/1000 patient-days (95% CI 2.2 to 2.8). Fever occurred at least once (229 fever events) among one-third of the participants during the study period. Fever was more likely to arise in the wheelchair users or bedridden than in ambulatory individuals (HR 1.9 (95% CI 1.3 to 2.8; p<0.01); in patients with moderate-to-severe rather than those with none-to-mild cognitive impairment (HR, 1.7 (95% CI 1.1 to 2.6, p=0.01); and in those whose care-need levels were ≥3 rather than ≤2 (HR, 4.5 (95% CI 2.9 to 7.0; p<0.01). The causes of fever were pneumonia/bronchitis (n=103), skin and soft tissue infection (n=26), urinary tract infection (n=22) and the common cold (n=13). Fever was cured in 67% and 23% of patients at home and in hospital, respectively, and 5% of patients each died at home and in hospital. Antimicrobial agents treated 153 (67%) events in the home medical care setting.

Conclusions

Fever was more likely to occur in those requiring higher care levels and the main cause of fever was pneumonia/bronchitis. Healthcare providers should consider the conditions of elderly residents with lower objective functional status.

Keywords: Geriatric Medicine, General Medicine (see Internal Medicine)

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first prospective, multicentre study to describe the status of fever among home-dwelling elderly.

The present study revealed the incidence and risk factor of fever among elderly persons under home medical management, diagnosis at fever onset and outcomes.

Some fever occurrences might have remained undetected.

Introduction

In the face of a rapidly ageing population combined with a diminishing number of children, the number of facilities to care for the elderly and of hospitals that can accept inpatients in Japan are inadequate.1 The predicted death toll for 2030 is 1.6 million, but where 400 000 of these deaths will occur has not been predicted.1 Under these conditions, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare in Japan has promoted home medical care/management rather than in-hospital care.2

In the Japanese home medical care system, physicians regularly make house calls to patients. Doctors regularly visit patients at home for about 20 min twice each month. Patients or their relatives can call for an emergency home visit on demand according to medical emergencies.3 The leading objectives of medical care at home are to manage brain and nervous system disorders, such as the sequelae of cerebral infarction, Parkinson's disease and dementia, followed by caring for those with cardiovascular disorders, respiratory disorders and malignant neoplasms.3

Among the elderly receiving home medical care, the major issues comprise fever and infection that impose heavy burdens on not only patients and their relatives, but also medical professionals, since events related to fever reportedly account for many night-time home visits in Japan.4 However, because healthcare providers are not always available to patients at home, unlike those in nursing homes,2 the actual incidence and frequency of infection can be difficult to ascertain. Thus, the incidence, risk factors and causes of fever need to be determined. Although the incidence of fever should be high because immune function decreases with ageing and chronic comorbidity,5 our previous retrospective study has only shown a fever incidence of 2.3/1000 patient-days among the home-dwelling elderly.6 The reported incidence of infection in nursing homes is quite similar to that in the home setting (∼4.1/1000 patient-days).7 However, the incidence of fever per se in nursing homes has not apparently been defined. In addition, we previously found that fever was more likely to occur in individuals with high care-need levels, and that the three most common causes were pneumonia/bronchitis, urinary tract, and skin and soft tissue infections.6 These three causes were similar to those identified by studies at nursing homes.8–11

However, the results of our previous retrospective cohort study at a single institution might not have been generally applicable. In addition, most information was obtained from medical records and thus the possibility cannot be ruled out that fever incidences were under-reported, and that measurements of risk factors and judgments regarding the causes of fever were inaccurate.

Thus, the present multicentre prospective cohort study aimed to determine the incidence of fever among elderly persons under home medical management, diagnosis at the time of fever onset and termination (cure at home, hospitalisation and death) from a pragmatic standpoint. Whether or not level of care-need, activities of daily living (ADL) and cognitive function can predict the onset of fever was also assessed.

Methods

Study design

Prospective cohort study.

Setting

The study was implemented at Seikyo Ukima, Kajiwara, Seikyo, Kita-adachi Seikyo and Akabanehigashi clinics that serve the 23 wards of Tokyo. All are located in residential areas within 15 km of downtown Tokyo (Tokyo Station) and are teaching clinics for senior residency programmes in family doctor training. Two to five full-time doctors at these clinics process an average of 50–200 outpatients/day (as of April 2012).

Participants

The participants comprised all patients aged ≥65 years who were medically managed at home by physicians from the abovementioned five clinics.

Follow-up

The selected patients were followed up between 1 October 2009 and 30 September 2010. Data from patients who could not be followed up because of hospitalisation, moving, entering a facility or death were censored. However, follow-up was restarted from the date when those individuals who were hospitalised during follow-up returned to medical management at home.

End point

The end points were onset of fever (≥37.5°C or ≥1.5°C above the individual's normal body temperature), diagnosis at onset and termination of fever (cured at home, hospitalised, death). To precisely determine fever rates, the investigators measured the temperatures of the participants at least once in every 2 weeks and questioned the patients and their families about fever occurrences during the previous 2 weeks.

Because the three most common causes of fever at nursing homes comprised pneumonia/bronchitis, skin and soft tissue infection and urinary tract infection, patients with fever were diagnosed using criteria based on examples from published studies of nursing homes (table 1).8 12–16 Physicians diagnosed all other diseases.

Table 1.

Diagnosis based on previously defined criteria

| Diagnosis | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Pneumonia | At least two of the following:

|

| Urinary tract infection | At least three of the following without an indwelling catheter:

|

| Skin and soft tissue infection | At least two of the following:

|

Prediction and adjustment variables

Age, sex, level of care needed, ADL, cognitive function, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) and medical devices (gastric fistula, domiciliary oxygen therapy, respiratory devices) were recorded or measured.

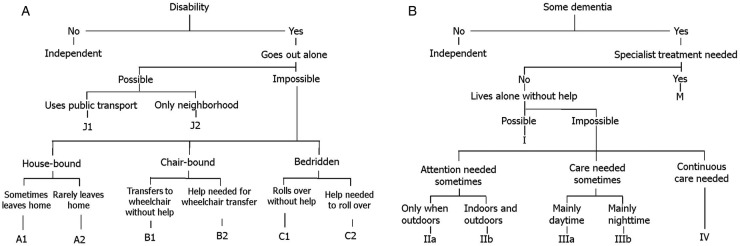

The Japanese Long-Term Care Insurance system classifies the needs of individuals aged ≥65 years as: requiring constant care due to being bedridden or having dementia; requiring some support for ADL, such as help with housework or physical help; and those not having either of these criteria, who might deteriorate into a state that requires constant care.1 2 This care-need classification is linked to the amount of care service benefits. Uniform criteria are applied nationwide to make objective determinations. Mental and physical status is initially examined (certification examination) by a municipal certification examiner, and then a computer reaches a decision (primary decision) based on the primary physician's written opinion, which includes medical and nursing care judgments, ADL and cognitive function determined by the individual's regular doctor (figure 1). A care-need certification committee comprising experienced professionals in public health, medicine and welfare reach a decision (secondary decision) based on the primary decision as well as the written opinion of the primary physician and then individuals are classified as having care-need levels from 1 to 5, support need or neither. The value for level of care-need increases as more care is needed, such as that for bedridden patients or those with dementia. Most individuals at care-need level five are usually bedridden.

Figure 1.

(A) Judgment of degree of independent daily living among disabled elderly persons. (B) Judgment of degree of independent daily living among elderly persons with dementia.

The influence of confounding by comorbidities was adjusted using the CCI, which is a scored indicator of comorbid disease that can estimate prognosis after 1 year.17 Comorbidities are assigned a predetermined score, such as one for myocardial infarction history and dementia, two for hemiplaegia and solid cancer without metastasis, and six for metastatic solid cancer. Higher total scores are associated with higher mortality 1 year later.

Statistical analysis

The incidence density of fever is shown using the person-time method, together with 95% CIs. This included multiple-failure events, which means all events of fever were counted over the period of home medical care. The period of hospital admission was excluded from the denominator for calculating incidence density.

In contrast, only the first episode of fever was considered in survival analyses since some participants experienced hospital admissions hampering home medical care and stayed there, which may have had an effect on risk of fever after the discharge from hospital. Therefore, we did not employ multiple failure-time data in the survival analyses. Instead we treated hospital admission as well as death as competing risk events of fever in the survival analyses using competing-risk method.18

The cumulative incidence of first fever occurrence was determined using competing-risk method. Between-group comparisons of cumulative incidence were assessed using the method developed by Pepe and Mori.19

To evaluate an independent effect of care-need level, ADL, cognitive function and medical devices on the occurrence of fever event, competing-risks regression was employed considering death and hospital admission as competing risk.20 Cognitive function and ADL closely correlated with level of care-need21 and thus were separately analysed. Model 1 included sex, age, ADL, cognitive function, CCI and medical devices (gastric fistula, domiciliary oxygen therapy and respirator). Model 2 included sex, age, care-need level, CCI and medical devices.

The level of significance was established at p<0.05 for all tests.

As the primary objective of this study was a description of incidence, we did not perform the exact sample size calculation. The priority was the participation of multiple clinics to expand the external validity. Based on the result of our previous retrospective cohort study,6 moreover, 95% CI of estimation was expected to be sufficiently narrow when including multiple institutions.

Statistical analyses were carried out using STATA V.12 (StataCorp. 2011. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP) and V.13 (StataCorp. 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP).

Ethical responsibilities

The Ethics Committee at Tokyo Hokuto Health Co-operative approved the present protocol.

Results

The proportion of 419 eligible and registered participants who required support or care during the 1-year study period was the same as the national average (table 2). Since all of the participants were followed up until the day they were hospitalised, moved or entered a residence facility or died, the follow-up rate was 100%.

Table 2.

Basic attributes of participants

| Participants (n=419) | Male (n=166) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Mean age±SD (years) at start of follow-up | 83.4±8.3 | |

| Total observation person-days | 91 415 | |

| Average observation±SD (days) | 217.1±133.0 | |

| Median observation (range) (days) | 237 (1–365) | |

| Activities of daily living (n) | J1-A2:185 | B1-C2:234 |

| Cognition (n) | 0–I:161 | IIa-M:258 |

| Level of care-need (n) | ||

| Support-need to care-need level 2 | 189 | |

| Care-need level 3–5 | 224 | |

| Gastrostoma (n) | 21 | |

| Respiratory device (n) | 2 | |

| Domiciliary oxygen therapy (n) | 28 | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index±SD | 2.7±2.0 | |

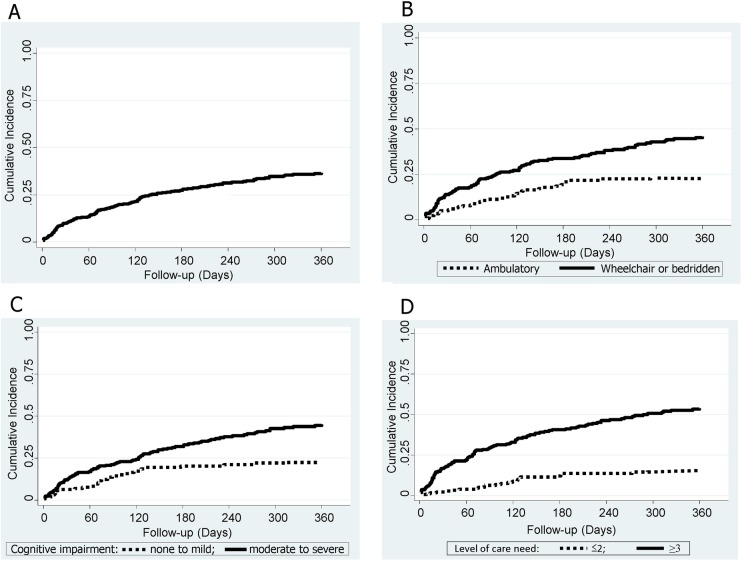

Overall, the total number of fever occurrences that occurred among 91 415 person-days was 229. Therefore, the incidence of fever was 2.5/1000 patient-days (95% CI 2.2 to 2.8). Cumulative incidence after 1 year follow-up estimated by competing risk method was 0.37 (95% CI 0.32 to 0.42). Fever occurred at least once among one-third of the patients over the study period of 1 year (figure 2A).

Figure 2.

(A) Cumulative incidence function for the first onset of fever estimated by competing risk method. (B) Comparison of cumulative incidence functions for the first onset of fever between wheelchair users or bedridden (B1-C2) and ambulatory (J1-A2) participants. (C) Comparison of cumulative incidence functions for the first onset of fever between participants with moderate-to-severe (IIa-M) and none-to-mild (0–I) cognitive impairment. (D) Comparison of cumulative incidence functions for the first onset of fever between participants with care-need levels ≤2 and ≥3.

Figure 2B compares the cumulative incidence function for the first onset of fever between wheelchair users or bedridden (B1-C2) and ambulatory (J1-A2) participants. Fever was significantly more likely to occur in wheelchair users or bedridden, than ambulatory individuals (p<0.01). After adjustments for sex, age, cognitive function, CCI and medical devices (gastric fistula, domiciliary oxygen therapy and respirator) using the competing-risk regression, the HR for wheelchair users or bedridden and ambulatory participants was 1.9 (95% CI 1.3 to 2.8, p<0.01; table 3 model 1).

Table 3.

Proportional hazards model for fever

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | ||

| Age | 1.02 (1.00 to 1.04) | 0.11 |

| Sex (F vs M) | 0.93 (0.65 to 1.34) | 0.71 |

| Activities of daily living (wheelchair users or bedridden vs ambulatory) | 1.88 (1.27 to 2.78) | <0.01 |

| Cognition (moderate-to-severe vs none-to-mild) | 1.69 (1.12 to 2.57) | 0.01 |

| Gastrostoma | 1.49 (0.81 to 2.75) | 0.20 |

| Respirator | 7.77 (2.42 to 24.97) | <0.01 |

| Domiciliary oxygen therapy | 0.74 (0.34 to 1.63) | 0.46 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 1.10 (1.01 to 1.21) | 0.03 |

| N=419 | ||

| Model 2 | ||

| Age | 1.03 (1.004 to 1.05) | 0.02 |

| Sex (F vs M) | 1.03 (0.70 to 1.50) | 0.88 |

| Care-need level (≥3 vs ≤2) | 4.49 (2.88 to 6.99) | <0.01 |

| Gastrostoma | 1.32 (0.74 to 2.34) | 0.35 |

| Respirator | 6.26 (2.95 to 13.29) | <0.01 |

| Domiciliary oxygen therapy | 0.64 (0.29 to 1.44) | 0.28 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 1.11 (1.02 to 1.21) | 0.01 |

| N=413* | ||

*Care-need levels were not determined in six participants and thus data from 413 patients were analysed in model 2.

F, female; M, male.

Also, figure 2C compares the cumulative incidence function for the first onset of fever between individuals with moderate-to-severe (IIa–M) and none-to-mild (0–I) cognitive impairment. Fever was significantly more likely to occur in those with moderate-to-severe than with none-to-mild cognitive impairment (p<0.01). After adjustments for sex, age, ADL, CCI and medical devices using the competing-risk regression, the HR for moderate-to-severe and none-to-mild cognitive impairment was 1.7 (95% CI 1.1 to 2.6, p=0.01; table 3 model 1).

Figure 2D compares the cumulative incidence function for the first onset of fever between individuals with care-need levels ≤2 and ≥3. Fever was significantly more likely to occur in those with care-need levels ≥3 than ≤2 (p<0.01). After adjustment for sex, age, CCI and medical devices using the competing-risk regression, the HR for ≥3 and ≤2 was 4.5 (95% CI 2.9 to 7.0, p<0.01; table 3 model 2).

The leading causes among all 229 fever events were pneumonia/bronchitis (n=103), skin and soft tissue infection (n=26), urinary tract infection (n=22) and common cold (n=13). The fever outcomes comprised cure at home (67%) or at hospital (23%) and death at home (5%) or in hospital (5%). Of the 229 events, 153 (67%) were treated in the home medical care setting using antimicrobial agents.

Discussion

This multicentre prospective cohort study revealed an incidence of fever among home-dwelling elderly of 2.5/1000 patient-days, and about one-third of the patients experienced a fever during a period of 1 year. Fever was more likely to occur among patients with care-need levels ≥3 than ≤2, those who are wheelchair users or bedridden rather than ambulatory and those with moderate-to-severe rather than none-to-mild cognitive impairment. The conditions most likely to cause fever were pneumonia/bronchitis, skin and soft tissue infection and urinary tract infection. These issues have only been investigated until now in a single-institution retrospective cohort study.6

The retrospective cohort study showed that fever was more likely to occur in patients requiring higher care-need levels. The Japanese Long-Term Care Insurance system classifies elderly persons living at home based on ADL and cognitive function as having care-need levels of 1–5, support need or neither.1 2 These indicators of need for support and care that are equally assessed in most individuals at the start of home medical care in the Japanese medical system, appear to comprise a distinct risk factor for the subsequent occurrence of fever events, but this was only apparent in Japan. This prospective study showed that ADL and cognitive function are sufficiently adaptable to also be considered as significant risk factors for fever events outside Japan. Fever was significantly more likely to occur in the wheelchair users or bedridden and in individuals with moderate-to-severe cognitive impairment, which means healthcare providers should consider these conditions and should measure the temperatures of elderly residents with lower objective functional status more frequently. Since elderly patients with lower ADL or cognitive function were more likely to develop pneumonia, its prevention via improving oral care or by pneumococcal vaccination should be useful for such patients.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The main strength of the present study is that it is the first prospective, multicentre effort to determine the status of fever among home-dwelling elderly. Several studies outside Japan have investigated these issues in nursing homes, which are considered fairly similar to home settings. However, we previously discovered the likely incidence and risk of fever in elderly people living at home in a retrospective cohort study at a single Japanese institution.6 The present multicentre study corrected the sample deviation associated with single facility studies. The prospective study design must have reduced under-reported fever events compared with the retrospective study and ADL and cognitive functions could be determined, unlike in the retrospective study.

Our retrospective study uncovered the leading causes of fever among elderly patients under home medical care. The top three sources were pneumonia/bronchitis, urinary tract infection, and skin and soft tissue infection, as they are in nursing homes outside Japan. However, that was a retrospective cohort study at a single institution and these diagnoses were obtained from medical records, and thus judgements regarding the causes of fever might be inaccurate. The present prospective study is reliable because these three source diseases were determined based on predefined criteria using examples from published studies of nursing homes8 12–16 (table 1).

Our study has some limitations. Even if the prospective study increased the frequency of fever, some occurrences might have remained undetected. Information about fever in the previous retrospective cohort study was obtained from medical records and thus fever was probably underestimated. We improved the detection rate by taking the temperatures of the patients at least once in every 2 weeks and questioning the patients and their families about fever during the previous 2-week interval. However, the incidence of fever increased only from 2.3 to 2.5. A possible reason for this is that fevers were defined as temperatures ≥37.5°C in the present study, compared with ≥37.2°C in the retrospective study. Since healthcare providers are not always at the homes of patients unlike in nursing homes and the temperatures of patients cannot be measured every day, some fevers might not have been reported to medical staff. In addition to regular temperature measurements by visiting nurses and/or trained home helpers, family members measured temperatures when they felt that the patient seemed ill. We considered that many such unreported events did not require medical services. That is, the events determined herein had been recognised by medical staff as being evident problems. Although fever might have been under-reported, we considered that the events analysed herein were thought to be true to the home medical care setting. Another potential limitation is the lack of vaccination data. Japanese elderly people are arbitrarily vaccinated against ailments such as pneumonia and influenza. These vaccines might be a confounder of fever and/or outcome.

Implications for future research

The need for home medical care will probably increase as the number of aged persons increases in many countries. Because healthcare providers are not always available on demand for those under home medical care, events such as fever might increase concerns about health for patients and their families and the burdens on healthcare providers might increase similarly to those in nursing homes.22 Doctors regularly attend patients at home according to the Japanese system of home medical care, whereas nurses assume this role in some other countries.23–25 Many such nurses have undergone specialised training24–26 and their ability to manage patients at home might be equivalent to that of doctors in Japan. However, extrapolation to other countries, or even other areas in Japan, might be difficult due to variations in social/medical circumstances. Therefore, further studies should investigate the issues addressed herein in other settings.

Conclusion

The incidence of fever among home-dwelling elderly patients was 2.5/1000 patient-days, with fever occurring in about one-third of the participants within a period of 1 year. Fever is more likely to occur among individuals with care-need levels ≥3 than ≤2, those who are wheelchair users or bedridden rather than ambulatory, and those individuals with moderate-to-severe rather than none-to-mild cognitive impairment. Thus, healthcare providers should consider these conditions and should measure the temperatures of elderly residents with lower objective functional status more frequently. The top three causes of fever were pneumonia/bronchitis, skin and soft tissue infection and urinary tract infection. The rate of pneumonia/bronchitis was particularly high. Strategies to prevent pneumonia from arising should be targeted at home-dwelling elderly persons with low ADL and/or cognitive function.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study has won the First Prize at the Japan Primary Care Association 2nd Conference. Guidance was received from the Jikei Clinical Research Programme for Primary Care at Jikei University School of Medicine. We thank all the staff at Seikyo Ukima Clinic, Kajiwara Clinic, Seikyo Clinic, Kita-adachi Seikyo Clinic and Akabanehigashi Clinic for providing valuable support.

Footnotes

Contributors: KY and MM contributed equally to this study. KY designed the study and participated in study implementation, data collection, data analysis and writing the manuscript. He also serves as guarantor. MM analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. TW and YF participated in study design, implementation and data collection. ST participated in study design and writing the manuscript. All the authors had full access to the data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the analysis. The study hypothesis arose before inspection of the data.

Funding: This study was supported by a 2008 research grant from the Japanese Academy of Family Medicine.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The Ethics Committee at Tokyo Hokuto Health Co-operative (Tokyo, Japan) approved the study (number 32/2009).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Transparency declaration: The lead author affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported.

References

- 1.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Central Social Insurance Medical Council. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/shingi/2r9852000001qd1o.html

- 2.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Implementation of home visit. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/seisakunitsuite/bunya/kenkou_iryou/iryou/zaitaku/index.html

- 3.National Federation of Health Insurance Societies. Investigation research report for medical care service at home. Tokyo: National Federation of Health Insurance Societies, 2008:1–172 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ishibashi R, Hayashi H, Katagiri J, et al. For death at home. Hosp Home Care 2009;17:17–21 (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Norman DC. Fever in elderly. Clin Infect Dis 2000;31:148–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yokobayashi K, Matsushima M, Fujinuma Y. Retrospective cohort study of the incidence and risk of fever in elderly people living at home: a pragmatic aspect of home medical management in Japan. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2013;13:887–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bentley DW, Bradley S, High K. Practice guideline for evaluation of fever and infection in long-term care facilities. Clin Infect Dis 2000;31:640–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zimmerman S, Gruber-Baldini AL, Magaziner J. Nursing home facility risk factors for infection and hospitalization: importance of registered nurse turnover, administration, and social factors. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50:1987–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith PW, Bennett G, Bradley S. Infection prevention and control in the long-term care facility. Am J Infect Control 2008;36:504–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.High K, Bradley S, Gravenstein S. Clinical practice guideline for the evaluation of fever and infection in older adult residents of long-term care facilities. Clin Infect Dis 2009;48:149–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garibaldi RA. Residential care and the elderly: the burden of infection. J Hosp Infect 1999;43:S9–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alberta Medical Association. Guideline for the diagnosis and management of nursing home acquired pneumonia. Alberta Medical Association, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loeb M, McGeer A, McArthur M. Risk factors for pneumonia and other lower respiratory tract infections in elderly residents of long-term care facilities. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:2058–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft-tissue infections. Clin Infect Dis 2005;41:1373–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamel HK. Managing urinary tract infections in the nursing home: myths, mysteries and realities. Internet J Geriatr Gerontol 2004;1. 10.5580/205c [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nicolle LE. Urinary tract infection in long-term-care facility residents. Clin Infect Dis 2000;31:757–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charlson ME. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haesook TK. Cumulative incidence in competing risks data and competing risks regression analysis. Clin Cancer Res 2007;13:559–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pepe MS, Mori M. Kaplan-Meier, marginal or conditional probability curves in summarizing competing risks failure time data. Stat Med 1993;12:737–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 1999;94:496–509 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Togami J, Nakahara M. Relationship between grade of care required and activities of daily living, dementia in elderly of day rehabilitation care. Yanagawariha Fukuoka Kokusai Kiyo 2009;5:57–60 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leibobitz A, Baumoehl Y, Habot B, et al. Management of adverse clinical events by duty physicians in a nursing home. Aging Clin Exp Res 2004;16:314–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tatara R. Palliative care by primary care team. Jpn Acad Home Care Physicians 2009;10:144–51 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katayama F. Learning from Hospice at U.S. Jpn Acad Home Care Physicians 2009;10:152–7 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riwa F. Home medical and nursing care in the U.S. and England. In: Sato H, Shimazaki K, eds Tomorrow's home care 5. Tokyo: Taiyosha, 2008:264–84 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Izawa T. Home medical and nursing care at Sweden. In: Sato H, Shimazaki K, eds Tomorrow's home care 5. Tokyo: Taiyosha, 2008:285–305 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.