Abstract

Objective

To study whether job strain, that is, psychological job demands and decision latitude, and sleep disturbances among persons with occasional neck/shoulder/arm pain (NSAP) are prognostic factors for having experienced at least one episode of troublesome NSAP, and to determine whether sleep disturbances modify the association between job strain and troublesome NSAP.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Setting

Stockholm, Sweden.

Participants

A population-based cohort of individuals with occasional NSAP (n=6979) who answered surveys in 2006 and 2010.

Outcome measures

Report of at least one episode of troublesome NSAP in 2010.

Results

The ORs for troublesome NSAP at follow-up were in individuals exposed to passive jobs 1.2 (95% CI 0.9 to 1.4); to active jobs 1.3 (95% CI 1.1 to 1.5); to high strain 1.5 (95% CI 1.0 to 2.4); to mild sleep disturbances 1.4 (95% CI 1.3 to 1.6) and to severe sleep disturbances 2.2 (95% CI 1.6 to 3.0). High strain and active jobs were associated with having experienced at least one episode of troublesome NSAP during the previous 6 months in persons with sleep disturbances, but not in individuals without sleep disturbances.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that high strain, active jobs and sleep disturbances are prognostic factors that should be taken into account when implementing preventive measures to minimise the risk of troublesome NSAP among people of working age. We suggest that sleep disturbances may modify the association between high strain and troublesome NSAP.

Keywords: musculoskeletal diseases, prevention, sleep, stress, work

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study adds new information to the limited knowledge about factors of importance for the risk of episodes of troublesome neck/shoulder/arm pain among working-age individuals who report occasional neck pain.

Its strength lies in its prospective design based on a general population of working age and the fact that prognostic factors were assessed prior to the outcome.

A further strength is the complete study sample and that several potential confounders were taken into account, even though unmeasured or residual confounding cannot be ruled out.

A limitation of the study is that we lack information about the duration of the exposures prior to baseline or about their occurrence during the 4-year follow-up period. This may limit the interpretation of the results.

Introduction

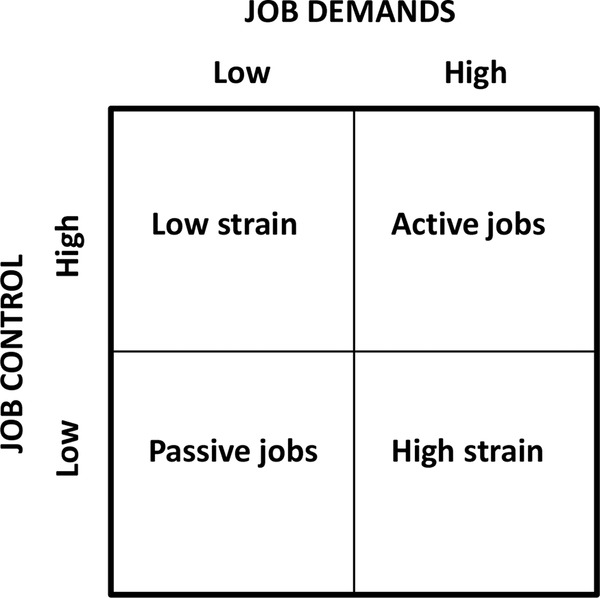

The prevalence of musculoskeletal pain is high overall.1 Among workers, neck/shoulder/arm pain (NSAP) is common, causing personal suffering and an economic burden for society.2–4 NSAP is a recurrent disorder that follows a course. Remissions, exacerbations and prior pain episodes seem to increase the risk of subsequent pain episodes.5–7 Although most people will experience neck pain to some degree, not everybody will experience chronic or troublesome neck pain.8 Studying the modifiable prognostic determinants of NSAP is important because it may help prevent severe conditions and promote recovery. Several determinants of the course of pain in the neck/shoulder have been suggested. Results from a cohort study in Sweden on the long-term prognosis of neck/shoulder pain showed that biomechanical exposure such as manual handling >50N and working with one's hands above shoulder level negatively influences the prognosis.9 Furthermore, individuals who take sick leave because of neck pain seem to be prone to subsequent episodes of lost time at work and prolonged disability.7 A recent study of persons with occasional neck pain reported that social factors such as economic stress and family income are associated with an increased risk of development of troublesome neck pain.10 In addition, work-related factors—physical, psychological and psychosocial—are considered important for the course of neck/shoulder pain.7 11 One widely used work-related model for various disorders is the job strain model, also known as the ‘demand-control model’.12–15 Here, high strain is described as a combination of high psychological job demands with low job decision latitude. This extensively studied model14 16 further defines a combination of high job demands and high job control as an active job situation, and a combination of low job control and low job demands as a passive job situation. It has been proposed that workers exposed to job strain face an increased risk of psychological strain and stress-related diseases.16–18 Recent research, however, has yielded contradictory results; some studies report a strong association between high strain and the prognosis of NSAP,19 20 while others report no associations.8 21 According to a recent review, several studies on job strain and NSAP are cross-sectional; thus, no assessment of temporality can be made.22

Several factors most likely modify the association between job strain and the trajectory from occasional NSAP to troublesome NSAP. One debated condition which may be associated with the impact of job strain is exhaustion17 in terms of prolonged fatigue and sleep disturbances.12 While sleep is considered an important part of physical restoration, curtailment of sleep by itself may be associated with the prognosis of musculoskeletal pain. Diverse associations between work-related psychological as well as psychosocial factors and sleep disturbances have been shown.23–26 However, few studies explore whether sleep disturbances play a role as an effect-measure modifier for the association between job strain and the risk of developing NSAP.12 23

To the best of our knowledge, no longitudinal study has investigated the effects of the exposures to job strain and sleep disturbances in a general population of working age reporting occasional NSAP at baseline. We therefore sought to study whether these conditions are prognostic factors for having experienced at least one episode of troublesome NSAP during the previous 6 months. We further sought to explore whether an association between job strain and troublesome NSAP is modified by sleep disturbances.

Methods

Study design

This longitudinal cohort study is based on the Stockholm Public Health Cohort (n=25 167), a population-based cohort set up by the Stockholm County Council to gather information about the determinants and consequences of significant contributors to the burden of disease.27

Study population

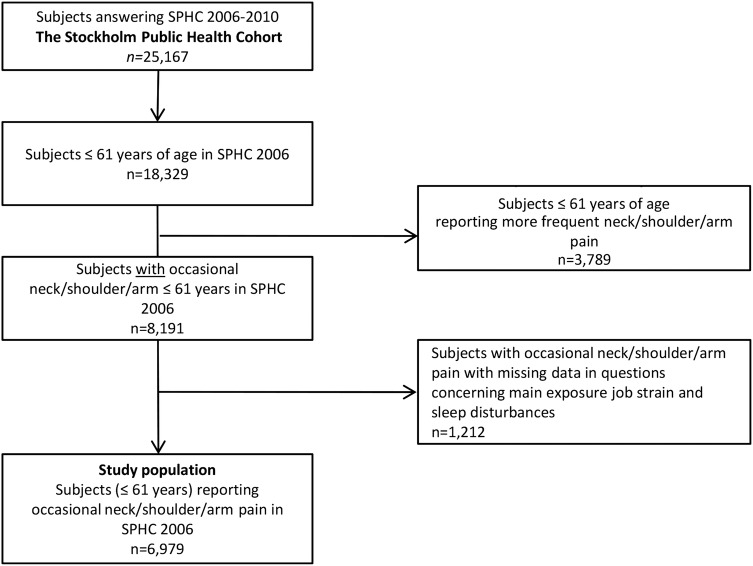

Participants aged 18–84 years were selected using area-stratified random samples of the Stockholm population, an urban region including 24 municipalities with approximately 1.4 million inhabitants (2002). Details about the data collection have been reported elsewhere.27 Randomly selected individuals (n=56 634; 18–84 years old) after stratification for gender and residential area received a baseline postal or web-based questionnaire in 2006. Sixty-one per cent of these (n=34 707) answered the questionnaire. A total of 25 167 of those who answered the baseline questionnaire answered a follow-up questionnaire in 2010, and members of this group constitute the Stockholm Public Health Cohort 06/10 (SPHC 06/10). For the present purpose, only those aged 61 years and below at baseline in SPHC 06/10 were included in order to limit the study to persons of working age, since the follow-up time was 4 years and the official retirement age in Sweden is 65. Those with missing data on the questions on high job demands, low job control and sleep were excluded from the cohort (n=1212). In addition, those who reported no NSAP or more frequent than occasional at baseline were excluded (n=3789; figure 1). Thus, the study population comprises persons who reported occasional NSAP at baseline (n=6979). Occasional pain was indicated if participants responded to the question “During the previous six months, have you experienced pain in neck, shoulder and/or arms?” with either “Yes, a couple of days in the last six months” or “Yes, a couple of days each month.”

Figure 1.

Flow chart of inclusion process.

Questionnaires

Baseline data were elicited with questions regarding demographic characteristics, physical and psychological health, physical and psychosocial work environment, lifestyle factors, socioeconomics, social relations and sick leave. These questions were included in the 2006 survey, as reported elsewhere.27

The potential prognostic factors studied were self-reported job strain; combinations of job demands and job control (high strain, active and passive jobs) and sleep disturbances—reported at baseline.

The job strain model

Job demands and job control were categorised according to the job strain model and analysed as follows: (1) low strain (low job demands and high job control), (2) active jobs (high job demands and high job control), (3) passive jobs (low job demands and low job control) and (4) high strain (high job demands and low job control; figure 2). Four questions in the baseline questionnaire were used for this purpose; two about job demands and two about job control. The original Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ) has five items on job demand and nine on job control.28 29 The use of a partial scale compared with a complete, multi-item job demands and control instrument is reportedly feasible, exhibiting high correlations to a complete instrument (Pearson's correlation coefficient, r=0.76–0.88); in addition, the present partial instrument assesses the same underlying concepts as the complete instrument.30 To test the internal consistency of the four questions used for job strain in the present study, Cronbach's α was calculated for job demands (α=0.53) and job control (α=0.77).

Figure 2.

The job strain model.14

The two questions used to measure job demands were:

“Do you have enough time to complete your assignments at work?” The answers were dichotomised into yes (yes, usually/always; yes, sometimes) and no (no, rarely; no, never).

“Are there contradictory demands involved in your job?” The answers were dichotomised into yes (yes, usually/always; yes, sometimes) and no (no, rarely; no, never).

The two questions used to measure job control were:

“Are you free to decide what needs to be done at work?” The answers were dichotomised into yes (yes, usually/always; yes, sometimes) and no (no, rarely; no, never).

“Are you free to decide how your work is to be carried out?” The answers were dichotomised into yes (yes, usually/always; yes, sometimes) and no (no, rarely; no, never).

Persons with an active job situation had a combination of high job demands (question a=no, b=yes) and high job control (question c=yes, d=yes). Those with a passive job situation had a combination of low job demands (question a=yes, b=no) and low job control (question c=no, d=no), and persons with job strain had a combination of high job demands (question a=no, b=yes) and low control (question c=no, d=no).

Sleep disturbances

Sleep disturbances were assessed with the question “Do you have difficulty sleeping?” The response options were no; yes, somewhat (classified as mild sleep disturbances) and yes, severe (classified as severe sleep disturbances). Mild and severe sleep disturbances were categorised as sleep disturbances in the stratified analysis. The question has been included in the Stockholm Public Health surveys since 2002, to determine longitudinally the prevalence of such disturbances among the population.27

Outcome

The outcome of having experienced an episode of troublesome NSAP during the previous 6 months was based on two questions in the 2010 follow-up survey. Participants who answered ‘yes’ to both of the following questions were defined as experiencing troublesome NSAP: “During the last six months, have you felt pain in your neck or upper back and/or shoulder or arms? If so, have these restricted your work capacity or hindered you in daily activities to some degree or to a high degree?”

Potential confounders

Potential confounders were chosen from the baseline survey and guided by knowledge from prior research and by clinical considerations.7 31 The potential confounders were age (continuous and 18–44/45–61 years), sex (men/women), smoking habits (daily), alcohol consumption (sometime during a period of 12 months), back pain during the previous 6 months (yes; more than 2 days), socioeconomic class (unskilled and semiskilled workers, skilled workers, assistant non-manual employee, intermediate non-manual employees, employed/self-employed/professional), low support at work from superiors (yes), low support at work from colleagues (yes), main physical workload in the past 12 months (sedentary, light, moderately heavy, heavy), time spent on household work per day (yes >5 h), economic stress based on the question “Did it happen that during the past 12 months you ran out of salary/money and had to borrow from relatives or friends in order to pay for food or rent?” (yes), country of birth (Sweden, elsewhere), leisure physical activity level (sedentary <2 h/week/active ≥2 h/week) and sleep disturbances (none or mild/severe; table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline sociodemographic and psychosocial characteristics in the study population of persons with occasional neck, shoulder and/or arm pain at baseline (n=6979)

| Low strain (n=5358) |

Active jobs (n=1003) |

Passive jobs (n=518) |

High strain (n=100) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| 18–44 | 2981 | 56 | 613 | 61 | 348 | 67 | 64 | 64 |

| 45–61 | 2377 | 44 | 390 | 39 | 170 | 33 | 36 | 36 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Men | 2145 | 40 | 384 | 38 | 158 | 30 | 32 | 32 |

| Women | 3213 | 60 | 619 | 62 | 360 | 70 | 68 | 68 |

| Country of birth | ||||||||

| Sweden | 4600 | 86 | 899 | 90 | 404 | 78 | 83 | 83 |

| Elsewhere | 758 | 14 | 104 | 10 | 114 | 22 | 17 | 17 |

| Socioeconomic class* | ||||||||

| Unskilled and semiskilled workers | 656 | 13 | 64 | 7 | 162 | 34 | 33 | 35 |

| Skilled workers | 611 | 12 | 62 | 6 | 76 | 16 | 11 | 11 |

| Assistant non-manual employees | 778 | 15 | 107 | 11 | 108 | 23 | 12 | 12 |

| Intermediate non-manual employees | 1358 | 26 | 321 | 33 | 90 | 19 | 24 | 24 |

| Employed/self-employed professionals, civil servants and executives | 1265 | 24 | 331 | 34 | 29 | 6 | 10 | 10 |

| Self-employed (other than professionals) | 492 | 10 | 84 | 9 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| Sleep disturbances | ||||||||

| None | 3861 | 72 | 601 | 60 | 326 | 63 | 54 | 54 |

| Mild/severe | 1497 | 28 | 402 | 40 | 192 | 37 | 46 | 46 |

| Workload | ||||||||

| Sedentary | 2207 | 41 | 464 | 46 | 192 | 37 | 36 | 36 |

| Light | 1572 | 29 | 272 | 27 | 119 | 23 | 18 | 18 |

| Moderately heavy | 1156 | 22 | 192 | 19 | 149 | 29 | 18 | 18 |

| Heavy | 409 | 8 | 74 | 7 | 56 | 11 | 27 | 27 |

| Low support at work from superiors (yes) | 458 | 18 | 321 | 32 | 183 | 35 | 69 | 69 |

| Low support at work from colleagues (yes) | 622 | 9 | 150 | 15 | 71 | 14 | 20 | 20 |

| Economic stress (yes)† | 367 | 7 | 77 | 8 | 73 | 14 | 16 | 16 |

| Household work | ||||||||

| >5 h/week | 2135 | 40 | 456 | 45 | 183 | 36 | 39 | 39 |

| Comorbidity LBP | ||||||||

| Yes, 2 days or more often during previous 6 months | 3318 | 62 | 648 | 65 | 345 | 67 | 67 | 67 |

| Smoking habits (daily) | 702 | 13 | 121 | 12 | 79 | 15 | 13 | 13 |

| Alcohol (yes, sometime during the past 12 months) | 4945 | 93 | 949 | 95 | 458 | 89 | 87 | 87 |

| Leisure physical activity level | ||||||||

| Sedentary <2 h/week | 477 | 9 | 102 | 10 | 83 | 16 | 18 | 18 |

| Active ≥2 h/week | 4877 | 91 | 895 | 89 | 432 | 84 | 81 | 81 |

*Socioeconomic class: based on occupation and education.

†Economic stress (“Did it happen that during the past 12 months you ran out of salary/money and had to borrow from relatives and friends in order to pay for food or rent?”). LBP, low back pain.

Job strain (low strain, active and passive jobs and high strain) was tested regarding confounding in the sleep disturbances model; sleep disturbances were considered to be potentially in the causal pathway between job strain and episodes of troublesome NSAP.

Statistical analysis

Numbers and proportions (%) for the variables were used to describe the baseline characteristics. Logistic regression models were used to assess associations between the prognostic factors and the outcome. Results are presented as ORs, along with 95% CIs.

Crude associations between (1) active jobs (high job demands/control) (2) passive jobs (low job control/demands) and (3) high strain as discrete factors on the one hand, and as a new episode of troublesome NSAP on the other, were calculated. Low strain (high job control/low job demands) served as the reference category. We also calculated crude associations between sleep disturbances (mild, severe and none) and troublesome NSAP.

Two regression models were built for the analyses: one with the four levels of job strain (low strain, active jobs, passive jobs and high strain) and one with the three levels of sleep disturbances (none, mild, severe). For each of the two regression models, potential confounding factors were added one at a time to the crude regression model. If a factor changed the crude OR by 10% or more, it was considered a confounder and was entered into the final model, in accordance with Rothman and Greenland.32 Finally, we stratified the analyses of job strain and troublesome NSAP by sleep disturbances/no sleep disturbances in a crude and adjusted model in order to study whether the effect of job strain was modified by sleep disturbances.

The final adjusted model for the exposures to active jobs, passive jobs and high strain included the confounders socioeconomic class, workload and support at work from one's superiors. In the final adjusted model for sleep disturbances, we included economic stress.

Statistical analyses used the STATA statistical software system V.11.

Results

The characteristics of the study population that experiences occasional NSAP at baseline (n=6979) stratified by the categories of the job strain model are presented in table 1. Sixty-one per cent (n=4260) of the cohort were women, and 57% (n=4006) were aged 18–44 years. The mean age of women was 41 years (SD 11) and of men 42 (SD 11) and did not differ between low strain, passive or active jobs and high strain. Of the cohort, 1003 persons (14%) reported active jobs at baseline in 2006, 518 (7%) reported passive jobs in 2010 and 100 (2%) reported high strain. In total, 2137 (31%) reported severe sleep disturbances at baseline. Twenty-four per cent (n=1659) of the cohort reported troublesome NSAP at follow-up (2010).

After control for confounding, high strain and active jobs at baseline were associated with at least one episode of troublesome NSAP experienced during the 6 months prior to follow-up in 2010 (table 2). The adjusted analyses showed an OR of 1.3 (95% CI 1.1 to 1.5) for active jobs, 1.2 (95% CI 0.9 to 1.4) for passive jobs and 1.5 (95% CI 1.0 to 2.4) for high strain, compared with the reference category low strain.

Table 2.

Associations between active jobs (high job demands/high control) and passive jobs (low job control/low job demands), high strain (high job demands/low job control) and sleep disturbances and the risk of experiencing at least one episode of troublesome neck/shoulder/arm pain

| Exposure | Number of experienced cases (total) | Crude OR (95% CI) |

p Value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low strain (reference) | 1219 (5358) | 1 | – | 1 | – |

| Active jobs | 257 (1003) | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.4) | 0.04 | 1.3* (1.1 to 1.5) | 0.01 |

| Passive jobs | 145 (518) | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.6) | <0.001 | 1.2* (0.9 to 1.4) | ns |

| High strain | 38 (100) | 2.0 (1.3 to 3.0) | <0.01 | 1.5* (1.0 to 2.4) | ns |

| No sleep disturbance (reference) | 1035 (4886) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Mild sleep disturbance | 547 (1905) | 1.4 (1.3 to 1.6) | <0.001 | 1.4† (1.3 to 1.6) | <0.001 |

| Severe sleep disturbance | 77 (188) | 2.5 (1.8 to 3.3) | <0.001 | 2.2† (1.6 to 3.0) | <0.001 |

The associations are presented as crude and adjusted ORs and 95% CIs.

*Adjusted for socioeconomic class, workload and support from superiors.

†Adjusted for economic stress.ns, non-significant.

Sleep disturbances at baseline were associated with at least one episode of NSAP during the previous 6 months reported at follow-up (table 2). The adjusted analysis yielded an OR of 1.4 (95% CI 1.3 to 1.6) for mild sleep disturbances and an OR of 2.2 (95% CI 1.6 to 3.0) for severe sleep disturbances, compared with the reference category no sleep disturbances.

Table 3 shows the results of the stratified analysis. In the stratum no sleep disturbances, the adjusted ORs for the association between active and passive jobs at baseline and troublesome NSAP at follow-up were 1.1 (95% CI 0.9 to 1.4) and 1.2 (95% CI 0.9 to 1.6), respectively, and for high strain OR 1.2 (95% CI 0.6 to 2.1). For the stratum sleep disturbances, the adjusted ORs between active and passive jobs at baseline and troublesome NSAP at follow-up were 1.3 (95% CI 1.0 to 1.7) and 1.0 (95% CI 0.7 to 1.5), respectively. The OR for high strain was 1.8 (95% CI 1.0 to 3.5).

Table 3.

Associations between active jobs (high job demands/high job control), passive jobs (low job control/low job demands), high strain (high job demands/low control) and troublesome neck, shoulder and/or arm pain, stratified for no sleep disturbances/sleep disturbances (mild/severe), presented as crude and adjusted ORs and 95% CIs

| No sleep disturbances |

Sleep disturbances |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure | Number of experienced cases (total) | Crude OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted* OR (95% CI) |

p Value | Number of experienced cases (total) | Crude OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted* OR (95% CI) |

p Value |

| Low strain (reference) | 808 (3890) | 1 | 1 | 411 (1468) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Active jobs | 129 (597) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.3) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.4) | ns | 128 (396) | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.6) | 1.3 (1.0 to 1.7) | 0.02 |

| Passive jobs | 83 (336) | 1.3 (1.0 to 1.7) | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.6) | ns | 62 (192) | 1.3 (0.9 to 1.8) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.5) | ns |

| High strain | 15 (54) | 1.4 (0.8 to 2.6) | 1.2 (0.6 to 2.1) | ns | 23 (46) | 2.6 (1.4 to 4.6) | 1.8 (1.0 to 3.5) | ns |

*Adjusted for economic stress.

ns, non-significant.

Discussion

The present results indicate that active jobs (high job demands/high job control) and high strain (high job demand/low job control) and sleep disturbances are factors that may be important for having experienced at least one episode of troublesome NSAP during the 6 months prior to follow-up in persons of working age with occasional NSAP. Furthermore, sleep disturbances seem to modify the prognostic effect of an active job situation and, in addition, a high strain situation. As sleep disturbances and NSAP are common complaints, our findings are important from a public health perspective.

The study population included individuals who reported occasional NSAP at baseline, of whom some subsequently experienced at least one period of troublesome pain at follow-up. Such a prognostic approach in longitudinal studies of the general population has until now been but little used.22 Job strain is a critical psychosocial work-related factor in the development of harmful work stress and is associated with the risk of several disorders.18 33 34 However, not all studies recognise job strain as a prognostic factor for NSAP.9 22 26 The discrepancy may be explained by sources of bias, different study designs or varied study populations; but results may also depend on differing definitions of neck/shoulder pain.22

Sleep is considered vital to the recovery of body and mind and has been linked to a state of altered metabolism—changes that, in turn, may be linked to, for example, diabetes and cardiovascular disease.35 36 In addition, the metabolic changes that result from sleep disturbance are similar to those related to stress.35 36 The present study suggests that sleep disturbances act as a modifier between the prognosis of troublesome NSAP and the impact of job strain. However, Canivet et al12 investigated sleep disturbances as a possible mediating factor in the pathway between job strain and chronic musculoskeletal pain but found no such association. A recent literature review25 concludes that strong evidence associates especially high demands at work (active jobs) with severe sleep disturbances. The modifying effect of sleep disturbances that we found may have different explanations, but since we cannot be sure of the temporality between the onsets of high strain and sleep disturbances, we can only speculate on the associations. It may be that sleep disturbance is a confounder as well as an effect-measure modifier. Furthermore, it may be that sleep disturbance is a mediator in the causal pathway between high strain and new periods of troublesome NSAP. If a causal interaction is present, the risk of developing troublesome NSAP for a person who experiences high strain or active jobs and sleeping disturbances may be higher than the sum of the effects of the two exposures.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The strength of the study lies in its prospective design based on a general population of working age and on the fact that prognostic factors were assessed prior to the outcome. A further strength is the complete study sample; moreover, several potential confounders were taken into account, even though we cannot rule out the risk of unmeasured or residual confounding, for instance, from other psychosocial factors like catastrophising and somatisation.37

The well-recognised job strain model was used to assess work-related stress.14 15 A frequently used questionnaire developed to measure the construct job strain is the JCQ,28 which comprises five items addressing job demands and nine addressing control. In SPHC 06/10, on which the present study is based, four items from the JCQ were used to measure the constructs. This was judged feasible based on a report of consistently high agreement between partial scales measuring job strain and a complete survey.30

A potential limitation is that the lower sensitivity of a shorter scale may increase the risk of non-differential misclassification of exposure (ie, in this case, the prognostic factors, resulting in a dilution of the true effect). However, the sensitivity of the shorter scales was reported to be high (r>0.94).30 In addition, low sensitivity of the exposure measure is mainly a problem when the exposure is common, and this is not the case with job strain.

Sleep disturbances were relatively common (31%). They were investigated with a single question, and this may lead to misclassification of this exposure and differential misclassification, thus a dilution of a true effect.

We used logistic regression for the analyses of the associations in the study. Since the outcome (ie, troublesome NSAP) is relatively common, the calculated OR might be higher than a corresponding relative risk, and the results should not be interpreted as such. We lack information about the duration of the exposures prior to baseline or about the presence of the exposures during the 4-year follow-up period. This may limit the interpretation of the results through a misclassification of exposure. Such a misclassification would most probably be non-differential. Some study participants classified as exposed at baseline might after a while be unexposed, and some study participants classified as unexposed at baseline may after a while be exposed, which might result in a dilution of a true association.

Selection bias is a potential threat to validity and may be present if the loss to follow-up differs among participants exposed and unexposed and if the loss is also related to the outcome.32 Additional analyses showed that the proportion of those exposed to job strain and sleeping disturbances differed only marginally between those who completed the follow-up and those who did not. Accordingly, selection bias may not be a problem in this study.

Job strain may be one of several important factors that influence various disorders and distress—among others, troublesome NSAP. In addition, it has been reported recently that there seems to be an association between stress-related factors such as high job demands and high strain and an unhealthy lifestyle overall.18

In summary, our results indicate that high strain, active jobs and sleep disturbances may be of importance for the prognosis of occasional NSAP, in that these factors are associated with episodes of troublesome NSAP. It is important for employers and caregivers to take the reported high strain, active jobs and sleep disturbances into account when implementing measures to minimise the risk of troublesome NSAP in workers. Still, additional large, prospective studies are needed to confirm our results and also to identify other modifiable prognostic factors for this public health problem.

Conclusion

Our results indicate that high strain, active jobs and sleep disturbances are prognostic factors that should be taken into account when implementing preventive measures to minimise the risk of troublesome NSAP among people of working age. Furthermore, we suggest that sleep disturbances may modify the association between high strain and troublesome NSAP.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: ER-B, WJAG, JH, LWH and ES contributed to the design and content of the study and to the interpretation of the results. ER-B and ES conducted the statistical analyses. ER-B, WJAG, JH, LWH and ES critically revised the different versions of the manuscript and all authors read the final version.

Funding: The Stockholm Public Health Cohort was financed by the Stockholm County Council. Financial support for the study was obtained from the AFA Insurance postdoc scholarship.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm, Sweden (Diary nr. 2013/497-32).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Picavet HS, Hazes JM. Prevalence of self reported musculoskeletal diseases is high. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:644–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feveile H, Jensen C, Burr H. Risk factors for neck-shoulder and wrist-hand symptoms in a 5-year follow-up study of 3,990 employees in Denmark. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2002;75:243–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cassou B, Derriennic F, Monfort C, et al. Chronic neck and shoulder pain, age, and working conditions: longitudinal results from a large random sample in France. Occup Environ Med 2002;59:537–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skillgate E, Magnusson C, Lundberg M, et al. The age- and sex-specific occurrence of bothersome neck pain in the general population—results from the Stockholm public health cohort. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2012;13:185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guzman J, Hurwitz EL, Carroll LJ, et al. A new conceptual model of neck pain: linking onset, course, and care: the Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33(4 Suppl):S14–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carroll LJ, Hogg-Johnson S, van der Velde G, et al. Course and prognostic factors for neck pain in the general population: results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33(4 Suppl):S75–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carroll LJ, Hogg-Johnson S, Cote P, et al. Course and prognostic factors for neck pain in workers: results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33(4 Suppl):S93–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haldeman S, Carroll LJ, Cassidy JD. The empowerment of people with neck pain: introduction: the Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33(4 Suppl):S8–S13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grooten WJ, Mulder M, Josephson M, et al. The influence of work-related exposures on the prognosis of neck/shoulder pain. Eur Spine J 2007;16:2083–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palmlof L, Skillgate E, Alfredsson L, et al. Does income matter for troublesome neck pain? A population-based study on risk and prognosis. J Epidemiol Community Health 2012;66:1063–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cote P, van der Velde G, Cassidy JD, et al. The burden and determinants of neck pain in workers: results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33(4 Suppl):S60–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canivet C, Ostergren PO, Choi B, et al. Sleeping problems as a risk factor for subsequent musculoskeletal pain and the role of job strain: results from a one-year follow-up of the Malmo Shoulder Neck Study Cohort. Int J Behav Med 2008;15:254–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ostergren PO, Hanson BS, Balogh I, et al. Incidence of shoulder and neck pain in a working population: effect modification between mechanical and psychosocial exposures at work? Results from a one year follow up of the Malmo shoulder and neck study cohort. J Epidemiol Community Health 2005;59:721–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Theorell T, Karasek RA. Current issues relating to psychosocial job strain and cardiovascular disease research. J Occup Health Psychol 1996;1:9–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karasek R. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job redesign. Adm Sci Q 1979;24:285–307 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karasek R, Baker D, Marxer F, et al. Job decision latitude, job demands, and cardiovascular disease: a prospective study of Swedish men. Am J Public Health 1981;71:694–705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindeberg SI, Rosvall M, Choi B, et al. Psychosocial working conditions and exhaustion in a working population sample of Swedish middle-aged men and women. Eur J Public Health 2011;21:190–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heikkila K, Fransson EI, Nyberg ST, et al. Job strain and health-related lifestyle: findings from an individual-participant meta-analysis of 118 000 working adults. Am J Public Health 2013;103:2090–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harcombe H, McBride D, Derrett S, et al. Prevalence and impact of musculoskeletal disorders in New Zealand nurses, postal workers and office workers. Aust N Z J Public Health 2009;33:437–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andersson HI. The course of non-malignant chronic pain: a 12-year follow-up of a cohort from the general population. Eur J Pain 2004;8:47–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fredriksson K, Alfredsson L, Ahlberg G, et al. Work environment and neck and shoulder pain: the influence of exposure time. Results from a population based case-control study. Occup Environ Med 2002;59:182–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park JK, Jang SH. Association between upper extremity musculoskeletal disorders and psychosocial factors at work: a review on the Job DCS Model's perspective. Saf Health Work 2010;1:37–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaila-Kangas L, Kivimaki M, Harma M, et al. Sleep disturbances as predictors of hospitalization for back disorders-a 28-year follow-up of industrial employees. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:51–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoogendoorn WE, Bongers PM, de Vet HC, et al. Psychosocial work characteristics and psychological strain in relation to low-back pain. Scand J Work Environ Health 2001;27:258–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. SBU - Swedish council on health technology assessment. Role of the work environment in the development of sleep disorders. 2013. Stockholm, Sweden. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanson LL, Akerstedt T, Naswall K, et al. Cross-lagged relationships between workplace demands, control, support, and sleep problems. Sleep 2011;34:1403–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Svensson AC, Fredlund P, Laflamme L, et al. Cohort profile: the Stockholm Public Health Cohort. Int J Epidemiol 2013;42:1263–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karasek R, Brisson C, Kawakami N, et al. The Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ): an instrument for internationally comparative assessments of psychosocial job characteristics. J Occup Health Psychol 1998;3:322–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Job Content Questionnaire Rf. (http://www.jcqcenter.org).

- 30.Fransson EI, Nyberg ST, Heikkila K, et al. Comparison of alternative versions of the job demand-control scales in 17 European cohort studies: the IPD-Work consortium. BMC Public Health 2012;12:62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hogg-Johnson S, van der Velde G, Carroll LJ, et al. The burden and determinants of neck pain in the general population: results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2009;32(2 Suppl):S46–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rothman KJ, Greenland S. Introduction to stratified analysis. 3rd edn Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams&Williams, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heraclides A, Chandola T, Witte DR, et al. Psychosocial stress at work doubles the risk of type 2 diabetes in middle-aged women: evidence from the Whitehall II study. Diabetes Care 2009;32:2230–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laszlo KD, Ahnve S, Hallqvist J, et al. Job strain predicts recurrent events after a first acute myocardial infarction: the Stockholm Heart Epidemiology Program. J Intern Med 2010;267:599–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Westerlund H, Alexanderson K, Akerstedt T, et al. Work-related sleep disturbances and sickness absence in the Swedish working population, 1993–1999. Sleep 2008;31:1169–77 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akerstedt T, Nilsson PM. Sleep as restitution: an introduction. J Intern Med 2003;254:6–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karels CH, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Burdorf A, et al. Social and psychological factors influenced the course of arm, neck and shoulder complaints. J Clin Epidemiol 2007;60:839–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.